Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Big Group Management

Uploaded by

Mohd Aminuddin0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views22 pagesnota

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentnota

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views22 pagesBig Group Management

Uploaded by

Mohd Aminuddinnota

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 22

1

Managing Student Behavior During Large

Group Guidance: What Works Best?

Christopher J. Quarto

Middle Tennessee State University

Managing Student Behavior 2

Abstract

Participants provided information pertaining to managing non-task-related behavior of

students during large group guidance lessons. In particular, school counselors were

asked often how often they provide large group guidance, the frequency of which

students exhibit off-task and/or disruptive behavior during guidance lessons, and

techniques they use to address such behavior. School counselors also described how

they were trained in classroom management and what they perceived to be the most

and least effective classroom management techniques.

Managing Student Behavior 3

Managing Student Behavior During Large

Group Guidance: What Works Best?

Among the various roles of school counselors is conducting large group guidance

(Dahir, 2001; Gysbers & Henderson, 2006). This is a powerful method of helping

students develop coping skills, enhance their interpersonal effectiveness and prepare

them to deal successfully with challenging developmental transitions (Jacobs &

Schimmel, 2005; Sears, 2005). Although school counselors may develop dynamic

group activities which they are excited to share with students as part of a developmental

guidance program, students may not share their enthusiasm and, thus, engage in non-

task-related or disruptive behaviors. As such, the impact of these activities is dependent

on how effectively school counselors can manage the behavior of students while they

are delivering the material. Indeed, Cowley (2003) and others (Evertson, Emmer &

Worsham, 2007; Geltner & Clark, 2005; Marzano, 2003) note that proper learning

cannot take place without effective classroom management. Likewise, Sink (2005)

maintains that Good teaching and classroom management skills are needed for the

effective delivery of guidance lessons (pg. 21). In this article, classroom management

and classroom discipline are used interchangeably to refer to techniques school

counselors use to manage off-task and disruptive behavior of students in the context of

large group guidance.)

It has been argued that school counselors who do not possess teaching

experience will experience greater difficulty managing disruptive behavior of students

during large group/classroom guidance activities (Criswell, 2005), although much of this

research is based on the perceptions of teachers and principals. A notable exception is

Managing Student Behavior 4

Peterson, Goodman, Keller and McCauley (2004) who conducted a study with school

counselor interns with and without teaching experience. They found that interns without

teaching experience reported difficulties with large group/classroom interventions (e.g.,

managing student behavior) and argued that counselor educators need to help non-

teacher trainees compensate for their lack of professional experience in a school

context. Perusse, Goodnough, and Noel (2001) conducted a national survey of

coordinators of school counseling programs which examined, among other things, the

curricular content of these programs. Coordinators were asked if they offered

specialization courses and 2% of the respondents indicated they offered a course in

classroom guidance, although there was no indication if students learned about

classroom management techniques in the course.

In a more recent study, Perusse and Goodnough (2005) surveyed elementary

and high school counselors with regard to the importance of graduate-level training for

24 content areas including classroom management. Although classroom management

was ranked lower than other content areas such as individual counseling, legal and

ethical issues, and consultation with parents and teachers, they (in particular,

elementary school counselors) still perceived it to be an important area to be covered in

the curriculum. Unfortunately, there is no mention in the aforementioned studies how

school counselor trainees learned about managing off-task and disruptive behavior of

students. This is an important omission given that school counselors as well as teachers

(Clark & Amatea, 2004) and principals (Zalaquett, 2005) view classroom guidance and

small group counseling as some of the most important functions of school counselors.

Managing Student Behavior 5

Given that a preponderance of the research conducted on classroom discipline pertains

to teachers, a brief review of relevant findings is presented next.

Wang, Haertel, and Walberg (1993) analyzed 86 chapters from annual research

reviews, 44 handbook chapters, 20 government reports, and 11 journal articles as well

as the results of 134 separate meta-analyses and found that there were 228 variables

which affected student achievement. Based on their findings, they concluded that

classroom management had the largest effect on achievement. Stage and Quirzo

(1997) conducted a meta-analysis of classroom discipline literature and found that the

more teachers can strike a balance between providing clear consequences for

unacceptable behavior and recognizing and rewarding good behavior, the more

effective their classroom management. Other researchers have found that getting off to

a good start at the beginning of the school year is also important. For example,

Evertson, Emmer & Worsham (2007) reported that beginning the school year with a

positive emphasis on management, arranging the room in a way conducive to effective

management, and identifying and implementing rules and operating procedures all

played an important role as to what happened later on in the school year.

In a meta-analysis, Marzano (2003a) found that the quality of teacher-student

relationships was the foundation for all other types of classroom management. In fact,

he noted that teachers who had high-quality relationships with their students had 31%

fewer discipline problems, rule violations, and related problems over a years time than

did teachers who did not have high-quality relationships. The most effective teacher-

student relationships were characterized by specific teacher behaviors: exhibiting

appropriate levels of dominance, exhibiting appropriate levels of cooperation, and being

Managing Student Behavior 6

aware of high-need students (i.e., those with mental, emotional, or behavioral

disorders), and having a repertoire of specific techniques for meeting their needs.

Cowley (2003) notes that there are various reasons students exhibit non-task-

related or disruptive behavior. In some cases, students become bored because the

content of the lesson does not interest them. In other cases, students lack the

motivation or self-discipline to perform well in school. Other students bow to peer

pressure as a way to be accepted by others or to prevent themselves from experiencing

negative repercussions. Whatever the case, school counselors who conduct large group

guidance lessons are challenged to develop and employ techniques to effectively

manage the behavior of students so all students benefit from the presentations and/or

activities. Unfortunately, little is known about this aspect of the school counselors role.

The purpose of the present study was to determine classroom management

techniques used by elementary and middle school counselors during large group

guidance activities. In particular, the researcher was interested in determining how

school counselors are trained in the use of classroom management techniques, how

often students exhibit disruptive or non-task-related behavior during classroom

guidance, what school counselors typically do to address such behavior, and school

counselors perceptions of the most effective and ineffective classroom management

techniques.

Method

Participants

Participants included 80 school counselors who worked in elementary (K- 8; n =

75) and middle (6 8; n = 5) public schools in 41 states. There was a preponderance of

Managing Student Behavior 7

Caucasian (86%) female (79%) participants who worked in rural (41%), suburban (36%)

and city (23%) schools. Sixty-five participants (81%) possessed professional teaching

experience and the entire sample possessed an average of 9.16 and 12.74 years of

school counseling and teaching experience, respectively (SD = 7.59 and 11.03).

Schools in which school counselors worked were chosen randomly from the American

School Directory, an internet-based web service which lists the names and addresses of

over 110,000 elementary and secondary schools across the United States. Only public

school counselors were chosen for inclusion in the present study so as to provide some

level of standardization among the participants. School counselors provided services to

as little as 15 and to as many as 1300 students (M = 518.58; SD = 254.06).

Instrument

Participants completed the School Counselor Classroom Management

Questionnaire (SCCMQ), a twenty-four item questionnaire developed for this study,

which was divided into two sections: (a) demographic information and (b) questions

pertaining to the nature and frequency of large group guidance services and the best

and worst techniques to use to manage off-task or otherwise disruptive behavior during

classroom guidance lessons. Specifically, school counselors were asked if they

provided large group guidance services at their schools and, if so, to how many different

groups of students they offered these services per week, how frequently students

exhibited off-task and/or disruptive behavior, and how school counselors typically

responded to these behaviors. School counselors were also asked to look over thirteen

classroom management techniques that may be employed by school counselors and to

rate their [techniques] perceived level of effectiveness in managing off-task/disruptive

Managing Student Behavior 8

behavior of students on a scale from 1 (Very Ineffective) to 6 (Very Effective). The

techniques were drawn from the research literature and classroom management and

group counseling textbooks and given to two counselor educators with an average of 17

years of university teaching experience in a school counseling program and six years of

school counseling experience at the elementary and secondary levels for preliminary

review. The techniques were also reviewed by an elementary school counselor with

seven years of experience. The educators and school counselor made suggestions as

to how a few of the items could be rephrased and recommended the addition of one

classroom management technique.

Procedure

Two hundred school counselors located in public schools across the United

States were contacted by letter requesting their voluntary participation in the study.

School counselors were informed of the nature and purpose of the study and, if they

agreed to participate, were asked to sign and return a consent form with their completed

questionnaire at their earliest convenience. School counselors did not provide any

identifying information so as to ensure confidentiality.

Results

Eighty school counselors returned useable questionnaires reflecting a 40% return

rate. Ninety-eight percent of the respondents indicated they provided large group

guidance with two-thirds of them providing this service to a minimum of 11 classes

within their respective schools; half of the participants provide large group guidance at

least once a week. Large group guidance lessons typically do not last longer than 45

Managing Student Behavior 9

minutes. Table 1 provides detailed information regarding large group guidance activities

provided by the participants.

Ninety-two percent of the school counselors indicated that students exhibit off-

task, disruptive, and/or inappropriate behavior during large group guidance lessons.

One to 10% of students in a typical classroom were perceived to exhibit such behavior

by the majority (83%) of the sample. School counselors were subsequently asked how

often they make a verbal comment or exhibit a non-verbal behavioral response (e.g.,

direct eye contact, hand gesture) to address off-task/disruptive behavior. The majority

indicated they make verbal comments (92%) or non-verbal behavioral responses (84%)

between 1 and 5 times per lesson, respectively. Table 2 lists the types of verbal

techniques used to address such behavior.

Table 2 results suggest that school counselors gravitate toward altering the

volume at which they speak as their primary technique to address disruptive and/or off-

task behavior; however it is important to note that one-fifth of the school counselors

used some other technique that was not a listed technique. They were subsequently

asked to specify what they did to address these problems. Their responses suggest that

they engage in behaviors which fall into the direct or indirect verbal technique

categories (e.g., Making a friendly reminder to the entire group about being good

listeners and watching the school counselor as he/she teaches the lesson; Asking

disruptive students a question about the topic at hand so as to reorient them to the

lesson; Praising students who exhibit on-task behavior).

School counselors were also asked about non-verbal behaviors used to address

disruptive and/or off task behavior and, once again, asked to rank order these methods.

Managing Student Behavior 10

Table 3 lists the types of non-verbal behavioral responses used to address such

behavior. Next, school counselors were asked to rate what they perceived to be the

most effective techniques with regard to managing off-task, disruptive, and/or

inappropriate behavior of students during large group guidance lessons. The results are

listed in Table 4.

School counselors perceived the most effective method of managing off-task or

disruptive behavior to be walking near a students desk while continuing to teach the

lesson. This is a non-verbal method of behavior control sometimes referred to as

proximity control. School counselors may perceive this to be effective because it does

not call attention to the student but still achieves the goal of reorienting them to the

lesson so they (i.e., counselors) can proceed in an orderly fashion. This was followed by

praising other students who are exhibiting on-task and/or appropriate behavior. Once

again, school counselors are using a method that is not directly aimed at the disruptive

student. Next, school counselors believed that praising students works well when they

exhibit on-task and/or appropriate behavior. This is the first technique which directly

addresses students of concern, but does so in a positive way. Redirecting students

attention to the task at hand was rated the fourth most effective technique. Thus, a

pattern emerged in which school counselors perceived the most effective techniques to

be positive or neutral and, in some cases, non-direct. Techniques which were more

punitive in nature were rated as least effective.

Finally, participants were asked how they learned classroom management

techniques. Specifically, the investigator was interested in determining whether school

counselors were trained in the use of classroom management techniques in their school

Managing Student Behavior 11

counselor training programs. This information was important given that many school

counselors have prior teaching experience (an average of twelve years of experience in

the current sample) and may have learned these techniques in teacher training

programs or, through trial-and-error experiences as teachers, figured out what seemed

to work best. Two-thirds (68%) of the school counselors did not learn about classroom

management techniques in their school counselor training programs. Of those who were

trained in the use of these techniques, the majority learned about them in one of three

ways: a) observing teachers or school counselors in the classroom, b) discussing

classroom management techniques as part of a class, or c) through assigned readings.

School counselors indicated that the most effective method of learning these techniques

was by observing teachers and school counselors utilize these techniques in the

classroom (61%). There were no differences among participants perceptions of what

constituted the most effective classroom management techniques as a function of prior

teaching experience.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to obtain specific information with regard

to how often school counselors perceive students to exhibit off-task and/or disruptive

behavior during large group guidance lessons. In addition, the examiner sought

information pertaining to how school counselors are trained to deal with problematic

behavior of students, how they address off-task and/or disruptive behavior, and their

perceptions of the most effective and ineffective classroom management techniques.

Given that many states are doing away with teaching experience as a

requirement for school counselor licensure, more students will enter school counselor

Managing Student Behavior 12

training programs without ever having stepped foot into a classroom as an educational

professional. As such, it is critical they are trained to manage groups of children so all

children may benefit from guidance lessons.

Large group guidance is one of the core components of a comprehensive school

counseling program which contributes to the academic, emotional and social

development of students (American School Counselor Association, 2003). Even

principals and teachers perceive this to be an important role of school counselors.

Although there were differences among the participants in the study with regard to how

often they conduct guidance lessons, nearly all indicated that they provide this service

with half of them conducting lessons at least once a week. One-third of the sample

indicated they conduct guidance lessons with more than 20 classes. Given that school

counselors come into contact with so many students, the likelihood of some of those

students displaying non-task-related and/or disruptive behavior is high. In fact, the

majority of the participants indicated that between 1 and 10% of the students in their

classrooms display such behavior and that they [school counselors] utilize verbal and

non-verbal tactics to address these behaviors a few times per lesson.

It is important for school counselors to have a repertoire of techniques they can

use to address off-task and/or disruptive behavior of students so as to eliminate barriers

to achievement and foster the emotional and social development of students with whom

they work. Participants in this study believed that positive and/or non-direct classroom

management techniques were most effective (e.g., walking near a disruptive student

during a lesson; praising students who are on task or a disruptive student when he/she

displays on task behavior) and negative or punitive techniques were least effective.

Managing Student Behavior 13

Given that the majority of the participants had prior teaching experience, their

perceptions were likely shaped by interactions with students in two different roles.

School counselors learned about classroom management techniques through different

methods, but believed the most effective way of learning these techniques was by

watching teachers or school counselors utilize the techniques while they taught their

lessons (i.e., observational learning). Thus, if counselor educators plan on offering

training experiences in classroom management, then it would make sense to structure

training experiences such that student counselors have the opportunity to observe

master teachers and school counselors teach lessons. Moreover, given that two-thirds

of the current sample received no training in classroom management in their school

counselor training programs and large group guidance is perceived to be an important

function by principals and teachers, it would behoove universities to incorporate this into

their curricula as a separate class or within the context of an applied experience such as

internship. Stressing which classroom management techniques work best based on the

perceptions of practicing school counselors would be an important component of such a

class.

There were many limitations of this study. First, the results were descriptive in

nature and did not provide answers to questions pertaining to the relationships between

variables (e.g., what are the predictors of effective classroom management?). Secondly,

the fairly low response rate limits the extent to which one can place confidence in the

findings of this study. The conclusions are an extrapolation from a limited sample of

school counselors. Finally, although the examiner conducted an exhaustive review of

the research literature pertaining to classroom management techniques for inclusion on

Managing Student Behavior 14

the questionnaire, it is possible that other techniques which were as equally or more

effective as the ones rated by school counselors in this study were not included.

The results of this study have given rise to new questions which can be

investigated in future studies. For instance, what is it about observing teachers or

school counselors that makes this such a good method of learning the art of classroom

management? In addition, is there a way this could be made into an even more effective

training method (e.g., having students co-lead classroom guidance lessons, trying out

some of these techniques themselves and being provided with immediate feedback

from the school counselor following the lesson or during the lesson using technology

devices such as the bug-in-the-ear)? Schwitzer, Gonzales and Curl (2001) discuss an

expanded simulation approach to train beginning counselors for professional work

environments which may prove to be a particularly effective way of training student

counselors in this area. However, student counselors may also benefit from learning

how to manage groups of children in other contexts (e.g., summer playground

supervisor, sports coach, Boy Scout or Girl Scout leader) which could be applied to the

classroom.

Managing Student Behavior 15

References

American School Counselor Association (2003). The ASCA national model: A

framework for school counseling programs (2

nd

Ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

Clark, M. A., & Amatea, E. (2004). Teacher perceptions and expectations of school

counselor contributions: Implications for program planning and training.

Professional School Counseling, 8, 132-140.

Cowley, S. (2003). Getting the buggers to behave 2. New York: Continuum.

Criswell, R. J. (2005). School counselors with and without teaching experience:

Attitudes of elementary, middle, and high school teachers. Dissertation Abstracts

International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 65, 3704.

Dahir, C. A. (2001). The national standards for school counseling programs:

Development and implementation. Professional School Counseling, 4, 320-327.

Evertson, C., Emmer, E. T., & Worsham, M. E. (2007). Classroom management for

elementary teachers (7

th

Ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Geltner, J. A. & Clark, A. (2005). Engaging students in classroom guidance:

Management techniques for middle school counselors. Professional School

Counseling, 9, 164-166.

Gysbers, N. C. & Henderson, P. (2006). Developing & managing your school guidance

and counseling program (4

th

Ed.). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling

Association.

Jacobs, E., & Schimmel, C. (2005). Small group counseling. In C. A. Sink (Ed.),

Contemporary school counseling (pp. 82-115). Boston: Lahaska Press.

Managing Student Behavior 16

Marzano, R. J. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research-based techniques

for every teacher. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum

Development.

Marzano, R. J. (2003a). Transforming classroom grading. Alexandria, VA: Association

for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Perusse, R., Goodnough, G. E., & Noel, C. J. (2001). A national survey of school

counselor preparation programs: Screening methods, faculty experiences,

curricular content, and fieldwork requirements. Counselor Education and

Supervision, 40, 252-262.

Peterson, J. S., Goodman, R., Keller, T., & McCauley, A. (2004). Teachers and non-

teachers as school counselors: Reflections on the internship experience.

Professional School Counseling, 7, 246-255.

Schwitzer, A. M., Gonzales, T., & Curl, J. (2001). Preparing students for professional

roles by simulating work settings in counselor education courses. Counselor

Education and Supervision, 40, 308-319.

Sears, S. J. (2005). Large group guidance: Curriculum development and instruction. In

C. A. Sink (Ed.), Contemporary school counseling (pp. 189-213). Boston:

Lahaska Press.

Sink, C. A. (2005). The contemporary school counselor. In C. A. Sink (Ed.),

Contemporary school counseling (pp. 1-42). Boston: Lahaska Press.

Stage, S. A., & Quirzo, D. R. (1997). A meta-analysis of interventions to decrease

disruptive classroom behavior in public education settings. School Psychology

Review, 26, 333-368.

Managing Student Behavior 17

Wang, M. C., Haertel, G. D., & Walberg, H. J. (1993). Toward a knowledge base for

school learning. Review of Educational Research, 63, 249-294.

Zalaquett, C. P. (2005). Principals perceptions of elementary school counselors roles

and functions. Professional School Counseling, 8, 451-457.

Managing Student Behavior 18

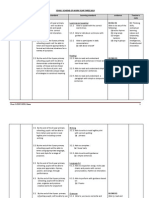

Table 1

Frequency of large group guidance activities

Item N %

How many different groups of students/classes

do you provide large group guidance?

1 5 groups/classes 17 21

6 10 groups/classes 12 15

11 15 groups/classes 12 15

16 20 groups/classes 10 13

More than 20 groups/classes 29 36

How often do you provide large group guidance?

Once a month or less 28 35

Once every couple of weeks 14 18

1 5 times per week 18 22

6 10 times per week 9 11

11 15 times per week 4 5

16 20 times per week 3 4

More than 20 times per week 4 5

How long do large group guidance sessions last?

15 30 minutes 53 66

31 45 minutes 22 28

46 60 minutes 5 6

Managing Student Behavior 19

Table 2

Frequency of verbal techniques used to address disruptive behavior

Technique Frequency of use (%)

Making voice louder and/or softer while 42

speaking to draw attention to you

Direct verbal comment (e.g., John, would 22

you please pay attention/stop

talking to you neighbor?)

Indirect verbal comment (e.g., There are 17

some people in here who need to

start paying attention & stop talking

to their neighbors.)

Other (specify) 19

Managing Student Behavior 20

Table 3

Frequency of non-verbal techniques used to address disruptive behavior

Technique Frequency of use (%)

Direct eye contact 50

Walking near the disruptive student while 30

continuing to teach the lesson

Silence (i.e., not talking for a few moments 20

during a lesson/session until student

discontinues off-task/disruptive behavior)

Managing Student Behavior 21

Table 4

Means and standard deviations of behavior management techniques

Item M SD

Walking near the disruptive students seat 5.10 1.05

while continuing to teach the lesson

Praising other students who are exhibiting 4.98 0.90

on-task and/or appropriate behavior

Praising the student when he or she happens 4.86 1.05

to exhibit an on-task and/or appropriate

behavior

Redirecting the students attention to the task 4.75 0.80

at hand

Requesting that the student exhibit on-task 4.48 1.03

and/or appropriate behavior

Requesting that the student move and/or 4.46 1.09

move closer to you during the lesson

Giving the student a warning to discontinue 4.30 1.32

exhibiting the behavior or else be issued

a consequence

Requesting that the student discontinue 4.22 1.04

the off-task, disruptive and/or

inappropriate behavior

Giving the student a tangible reward (e.g., 3.92 1.27

sticker) for exhibiting on-task and/or

appropriate behavior

Withdrawing a privilege (e.g., recess time) 3.68 1.43

Placing the student in a time-out 3.45 1.37

Ignoring the off-task and/or disruptive behavior 2.97 1.28

Requesting that the student place his/her name 2.68 1.46

on the blackboard

Managing Student Behavior 22

Biographical Statement

Christopher J. Quarto, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Department of

Psychology at Middle Tennessee State University. Dr. Quarto teaches practicum and

testing courses in the Professional Counseling program and operates a part-time private

practice in Murfreesboro. His research interests include school counselor credibility,

clinical supervision, and the creative use of brief therapy techniques in counseling.

You might also like

- Be: Affirmative / Negative: Verb Be - Is/ Are / AmDocument10 pagesBe: Affirmative / Negative: Verb Be - Is/ Are / AmMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Year 6 Page 38Document7 pagesYear 6 Page 38Mohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6aishah abdullahNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Mohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6aishah abdullahNo ratings yet

- 014 PenulisanDocument6 pages014 PenulisanMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Mohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6aishah abdullahNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6: 1. Ask and Answer Questions Based On The InformationDocument5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6: 1. Ask and Answer Questions Based On The Informationaishah abdullahNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6aishah abdullahNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Plan English Language Year 6Mohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 (Week 1)Document5 pagesUnit 3 (Week 1)Christer Ronald SaikehNo ratings yet

- Bi Pemahaman: Sumatif 1: BIL A: 1 B: 0 C: 0 D: 8 AR1: BIL A: 1 B: 0 C: 2 D: 6Document4 pagesBi Pemahaman: Sumatif 1: BIL A: 1 B: 0 C: 0 D: 8 AR1: BIL A: 1 B: 0 C: 2 D: 6Mohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Wordsearch 1Document2 pagesWordsearch 1Mohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- RPT English Y6 2020Document22 pagesRPT English Y6 2020Mohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Tips Upsr 2016Document24 pagesTips Upsr 2016Zalina JamalludinNo ratings yet

- 014 Notes OnlyDocument48 pages014 Notes OnlyMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Jadual WaktuDocument1 pageJadual WaktuMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Study Tips PDFDocument8 pagesStudy Tips PDFMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Table of Specifications (JSU) A Guide to Assessing English Writing SkillsDocument7 pagesTable of Specifications (JSU) A Guide to Assessing English Writing SkillsMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Boat Arm Nail: Match The Picture With The Correct WordDocument5 pagesBoat Arm Nail: Match The Picture With The Correct WordMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Penulisan - AnswerDocument17 pagesPenulisan - AnswerMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 LINUS YEAR 2Document10 pagesUnit 1 LINUS YEAR 2probs4mathNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 (Week 1)Document6 pagesUnit 1 (Week 1)Aby AbbyNo ratings yet

- Rancangan Pengajaran Tahunan BI Tahun 3 KSSR - Yearly Scheme of Work Year Three 2013Document37 pagesRancangan Pengajaran Tahunan BI Tahun 3 KSSR - Yearly Scheme of Work Year Three 2013mrdan100% (1)

- Action ResearchDocument21 pagesAction ResearchChe'gu HusniNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Dependence SyndromeDocument3 pagesAlcohol Dependence SyndromeMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Informal AssessmentDocument18 pagesInformal AssessmentMohd AminuddinNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan English Year 4Document7 pagesLesson Plan English Year 4Norhanim Bt Basiran100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 5323 - BUS301 ExamDocument5 pages5323 - BUS301 ExamPhillipsNo ratings yet

- Resume of Luvenia - RichsonDocument1 pageResume of Luvenia - Richsonapi-26775342No ratings yet

- School Safety Assessment Tool AnalysisDocument21 pagesSchool Safety Assessment Tool AnalysisRuel Gapuz ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Demonstration Teaching General GuidelinesDocument2 pagesGuidelines For Demonstration Teaching General GuidelinesAmor Rosario EspinaNo ratings yet

- SpinozaDocument310 pagesSpinozaRamy Al-Gamal100% (4)

- 7 Keys Successful MentoringDocument4 pages7 Keys Successful MentoringHarsha GandhiNo ratings yet

- Recomandare DaviDocument2 pagesRecomandare DaviTeodora TatuNo ratings yet

- May 2010 IB ExamsDocument2 pagesMay 2010 IB Examsstarr_m100% (1)

- AICB Compliance DPSDocument7 pagesAICB Compliance DPSAravind Hades0% (1)

- History of Philippine Cinema Research Paper TopicsDocument4 pagesHistory of Philippine Cinema Research Paper Topicsfvg2xg5rNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Growth of Telecom Industry in India & ChinaDocument38 pagesFactors Affecting Growth of Telecom Industry in India & ChinashowstoppernavNo ratings yet

- MGN 303Document11 pagesMGN 303Arun SomanNo ratings yet

- CV Sufi 2 NewDocument2 pagesCV Sufi 2 NewMohd Nur Al SufiNo ratings yet

- Isph-Gs PesDocument13 pagesIsph-Gs PesJeremiash Noblesala Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- The What Why and How of Culturally Responsive Teaching International Mandates Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument18 pagesThe What Why and How of Culturally Responsive Teaching International Mandates Challenges and Opportunitiesapi-696560926No ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - What Is AlgaeDocument20 pagesLesson 1 - What Is AlgaeYanyangGongNo ratings yet

- ETHICS AND VALUES EDUCATION: What is PHILOSOPHYDocument26 pagesETHICS AND VALUES EDUCATION: What is PHILOSOPHYdominic nicart0% (1)

- District 308 B2 Leo Cabinet 2015-16-1st e NewsletterDocument17 pagesDistrict 308 B2 Leo Cabinet 2015-16-1st e NewsletterminxiangNo ratings yet

- Precalculus Honors ProjectDocument2 pagesPrecalculus Honors Projectapi-268267969No ratings yet

- Opio Godfree RubangakeneDocument4 pagesOpio Godfree RubangakeneOcaka RonnieNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Education at Nature-Based MuseumsDocument19 pagesClimate Change Education at Nature-Based MuseumsMaria Emilia del CastilloNo ratings yet

- Cognitive and Metacognitive ProcessesDocument45 pagesCognitive and Metacognitive ProcessesjhenNo ratings yet

- 2018 Al Salhi Ahmad PHDDocument308 pages2018 Al Salhi Ahmad PHDsinetarmNo ratings yet

- Bsbsus201 R1Document4 pagesBsbsus201 R1sanam shresthaNo ratings yet

- LP 5Document2 pagesLP 5api-273585331No ratings yet

- Sesotho HL P3 May-June 2023Document5 pagesSesotho HL P3 May-June 2023bohlale.mosalaNo ratings yet

- Edwards Groves 2014Document12 pagesEdwards Groves 2014Camila LaraNo ratings yet

- Docshare - Tips - CBC Housekeeping NC II PDFDocument98 pagesDocshare - Tips - CBC Housekeeping NC II PDFDenver ToribioNo ratings yet

- 1 GEN ED PRE BOARD Rabies Comes From Dog and Other BitesDocument12 pages1 GEN ED PRE BOARD Rabies Comes From Dog and Other BitesJammie Aure EsguerraNo ratings yet

- McManus Warnell CHPT 1Document46 pagesMcManus Warnell CHPT 1CharleneKronstedtNo ratings yet