Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Well-B Eing: The Concept of Well-Being

Uploaded by

mikadikaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Well-B Eing: The Concept of Well-Being

Uploaded by

mikadikaCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Well-Being

Richard Kraut

The Concept of Well-Being

In ordinary speech, well-being is often used interchangeably with such terms as

health, happiness, and prosperity (see happiness). To be concerned about

someones well-being is to care whether he is doing or faring well. The word well

that appears in these expressions plays an evaluative role it is the adverbial form of

the adjective good, and of course good is a grade we use to evaluate things. If

someone is well-off, his life is good. Hence, it is not surprising that we commonly

move back and forth so easily between well-being and such terms as health,

happiness, and prosperity: most people assume that the life of a human being is

a good one that someone living such a life is faring well only if it has at least some

measure of these goods.

Philosophers nonetheless make a distinction that is not often observed in everyday

speech: they say that to be a constituent of well-being is one thing, and to be a means

to well-being is another. Take physical health, for example: one might believe that it

is a necessary pre-condition of well-being, but that it is to be sought and welcomed

only because of what it leads to or makes possible. In that case, one is not taking it to

be a constituent of well-being. It is not, as we might put it, intrinsically valuable (see

intrinsic value). On the other hand, one might hold that being physically healthy

is in itself good for us, whether or not it leads to further results. In that case, one is

regarding health as a component or constituent of well-being. It is, in other words,

intrinsically good.

The question, What is well-being? can thus be interpreted to mean Which

things are intrinsically good for an individual? So understood, it is the same

question that was raised in antiquity by Greek and Roman philosophers. For such

thinkers or schools of thought as Socrates (469399 bce), Plato (427347 bce),

Aristotle (384322 bce), the Stoics, and the Epicureans, the deepest question of

practical reasoning the one that underlies all other ethical questions is: what is

the highest or ultimate good (see aristotle; hellenistic ethics; highest good;

plato; stoicism)? Aristotle, for example, observes near the beginning of the

Nicomachean Ethics (2000) that some goods are sought for the sake of others, and

then argues that it cannot be that every good we pursue is desirable only for the sake

of something else. There must be something, he insists, that is desirable in itself and

not sought for the sake of anything else, and that goal must be the one for the sake

of which all others are to be sought. He regarded it as an open question, to be

answered by philosophical methods, what that ultimate good is. The word he applies

to it is the common Greek term eudaimonia, which combines the adverb eu, meaning

The International Encyclopedia of Ethics. Edited by Hugh LaFollette, print pages 54425450.

2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Published 2013 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

DOI: 10.1002/ 9781444367072.wbiee099

well, and the word for a god, daimon (see eudaimonism). Hence, Aristotles term

eudaimonia, which he equates with living or faring well, is like our word well-being,

in three respects. First, both incorporate an evaluative notion that of wellness.

Second, eudaimonia, as with well-being, consists in something, and it can be pursued

only if one identifies what it consists in. Third, what it consist in must be something

that is not merely instrumentally good.

It is common to use the words good and bad elliptically to say, for example,

that health is good and disease bad, when what we mean is that health is good for

someone and disease bad for someone, namely the individual who is healthy or ill.

Of course, any instance of health is always the health of someone, but to say that

health is good for someone goes beyond saying that it is the health of someone.

Tospeak of health as good for the healthy person is equivalent to calling it beneficial

for or advantageous to him, or in his interest (see good and good for).

Some philosophers, nonetheless, insist upon the importance of a nonelliptical use

of good. Perhaps the clearest example is provided by G. E. Moore (18731958; see

moore, g. e.). He holds in Principia Ethica (1903) that goodness is the fundamental

property to which all practical reasoning must attend, but he is not talking about the

property of being advantageous to or good for anyone. Rather, he is proposing that

there is such a thing as impersonal or absolute goodness goodness period, or

simpliciter, or sans phrase.

Moore believes, for example, that beauty is absolutely good. To prove this, he asks

us to imagine two worlds, both devoid of people: one entirely beautiful, the other

wholly ugly. Is not the first world better than the second, he asks, even though there

is no one for whom it is better? It clearly is, he replies, and that is because it contains

something that is, quite simply, good: beauty. He accepts the common assumption

that the value of a beautiful world would be immeasurably increased were it occupied by people who enjoy the contemplation of its beauty. That, he holds, is because

of the absolute value of such pleasures. For Moore, both beauty and the enjoyment

of beauty are good (period). Their being good does not consist in their being good

for anyone.

In fact, he believes that it is misleading to speak of anything as good for someone,

or my good, or your good. Rather than say that the pleasure I take in contemplating

beautiful things is good for me, or that my good consists in such enjoyment, we

should say instead: Such a pleasure is absolutely good, and I am the one whose

pleasure it is. It is not in relation to me that aesthetic pleasure is good. It is simply a

good thing, and I should seek that kind of pleasure because my doing so increases

the amount of value in the universe. Moore is attracted to this way of thinking

because it leaves no room for rational self-interested motivation, and opens the door

to an impartial stance towards the universe. One is not to maximize what is good for

oneself, or ones family, or ones own group, however large that policy, he holds,

rests on a confusion. Clear thinking shows that what is to be maximized is the

amount of good that exists in the universe.

These points about Moore are relevant to the topic of well-being, because many

contemporary philosophers use well-being to designate a condition that is good

for the well-off individual. So used, to be concerned about someones well-being is

to care about whether his or her life contains things that are good for that individual.

It is to ask whether the person living that life is benefiting from living it. Moore,

then, has no theory of well-being in this sense rather, he is opposed to the idea that

well-being of this sort is worth caring about. For the same reason, if we take Aristotle

and other thinkers of Greek and Roman antiquity to be offering, in their reflections

on eudaimonia, theories about well-being, and we equate well-being, as many

philosophers do, with what is good for an individual, then we must be prepared to

take those ancient philosophers to be theorizing not about what Moore calls

absolutegoodness but about what is noninstrumentally advantageous or beneficial.

Alternatively, if we use the word well-being in the way that even Moore is talking

about it, no less than are philosophers who propose theories about what constitutes

an individuals advantage, then we risk confusion: some theories of well-being will

be about what is good (period), and others about what is good for someone. To

avoid misunderstanding, it is best to abide by common philosophical usage and to

treat theories of well-being as theories about what is noninstrumentally good for

someone. So used, we are making a substantive and contestable claim if we say that

well-being ones own or that of others should be among ones ultimate goals.

The concept of well-being, as we have seen, is best understood as the concept of

what is good for an individual, but in common usage good for and bad for have

a wider range. We can say, for example, without any sense of oddity, that it is bad for

an automobile to sit idly in the garage for many months, or that it is good for it to be

driven occasionally. However, it would be peculiar to talk about the well-being of a

car. Well-being is something that belongs above all to human beings and other

animals, rather than to plants and artifacts (see animals, moral status of).

Furthermore, a concern for the well-being of a person or a cat or a dog is a concern

for the whole life of that individual, or a significant stretch of it. Someone who felt

an urge to give you a momentary benefit would not be said to care about your

well-being. So, when we talk about well-being, we assume that lives have a temporal

duration and shape, and a concern for well-being must take into account what is

good for a person over that longer period of time. A similar point is made by Aristotle

when he remarks that no one can be eudaimon (the adjectival form of the noun

eudaimonia) for a day or any other brief period just as springtime is not simply the

appearance of a single swallow.

The term subjective well-being has recently been used by experimental

psychologists to designate a certain state of mind that they believe to be open to

scientific investigation. Subjects are asked how they feel either about the present

moment, or about their lives as a whole, or about certain dimensions of their lives.

Similar experiments can be conducted in which subjects are asked to rate the

intensity of pain on a scale between 1 and 10. Results can be aggregated and

conclusions drawn about the economic or political conditions that are correlated

with these states of mind; the effectiveness of various drugs in alleviating pain can

also be assessed. Such studies can be of great interest, insofar as we want to know

how people are feeling about their lives and how they respond to pain. However, by

their nature, these investigations are not addressed to the evaluative question that is

asked by philosophers when they discuss the topic of well-being. Philosophers who

reflect on well-being want to know what really is good for someone, not what seems

to be good. Psychologists, by contrast, are not in the business of making evaluations,

but are searching for the causes of certain states of mind a sense of well-being, or

happiness, or pleasure, or their opposites. The term subjective well-being is

therefore misleading if it suggests that empirical studies of mental states tell us what

is good for us. It may indeed be true that when one feels happy about ones life, that

is a good state to be in. However, whether it is good or not is a matter that is open to

and can be resolved only through philosophical inquiry.

Theories of Well-Being

Aristotle seeks a theory of human well-being a theory that is applicable not merely

to Greeks or to the fourth century, but to all people at all times. He holds that

virtuous activity (i.e., the exercise of such excellent qualities as wisdom, courage,

and justice) is the central ingredient of human well-being, but that it is not by itself

sufficient for eudaimonia, because human beings, no matter how virtuous, are

vulnerable to such misfortunes as enslavement or the depredations of tyrants. The

Stoic school, founded by Zeno of Citium (334262 bce) one generation after

Aristotle, departs from him in precisely that respect: it takes virtuous activity to be

the only good, and the failure to attain it as the only evil. A third conception of

well-being was endorsed by the Epicureans (another school founded soon after

Aristotles death): they took pleasure to be the sole good, and pain the sole evil.

The term hedonism is often used as a label for this doctrine (see hedonism;

pleasure). Notice that the Epicurean doctrine is even broader in scope than Aristotles. It proposes not only a conception of human well-being, but a theory about

the good of all creatures. For an animal to live well, according to the Epicureans, is

for it to live pleasantly. Even if what pleases animals does not please us, we have the

same ultimate goal that they do.

Aristotle would agree with the Epicureans to this extent: a life devoid of pleasure,

he insists, cannot be eudaimon. His picture of a well-lived life is that of a human

being who enjoys being wise, just, and courageous (and has the resources to act in

these ways). How does this differ from the Epicurean theory? Pleasure, for Aristotle,

should not by itself be our ultimate end; rather, his thesis is that our proper ultimate

end enjoyable virtuous activity has pleasure in it as one component. Pleasure is

one kind of intrinsic good but not the only kind. And he believes that some kinds of

pleasure are not good at all. But for the Epicureans, all pleasures are good, nothing

other than pleasure is noninstrumentally good, and our ultimate end is not the

pleasure of virtuous activity but pleasure alone.

Hedonism was revived in the modern era, and some authors combined it with the

principle that our supreme goal should be to produce the greatest quantity of good.

The result is utilitarianism the doctrine embraced and popularized by Jeremy

Bentham (17481832) and John Stuart Mill (180673), and refined by Henry

Sidgwick (18381900), that the supreme moral rule commands us to maximize

pleasure (see bentham, jeremy; greatest happiness principle; mill, john

stuart; sidgwick, henry; utilitarianism). Well-being, according to these

utilitarians, consists simply in pleasant consciousness. However, one is not to be

concerned solely with ones own well-being, or with the well-being of ones own

society or political community. Even a concern with human well-being would be too

narrow a focus. The best that one can do is to increase, as fully as possible, the total

amount of well-being of humans and of any other creature that is capable of

well-being. Moore too holds that our supreme goal is to maximize something, but as

we have seen, he thinks that it is not well-being (what is good for someone) that is to

be maximized, but good simpliciter.

Mills conception of well-being is subtle and complex because he rebels against

Benthams doctrine that only the quantity of pleasure matters. For Bentham,

pleasures are to be assessed solely along the following dimensions: intensity,

duration, certainty, temporal propinquity, fecundity (likelihood of producing more

pleasure), and purity (unlikelihood of producing pain). Mill protests that Bentham

is attentive merely to the quantitative aspect of pleasure, and entirely overlooks their

qualitative differences. Some pleasures are higher (he is thinking, for example, of

the pleasures of reading great poetry), others lower (the satisfaction of desires for

food, drink, and sex). To determine that one kind of pleasure is higher than another,

he says, we need only ask about the preferences of those who have experienced both.

Even if Mill is right that this is a reliable way to assess the quality of pleasures, his

attempt to improve on Bentham is problematic, and few hedonists have followed his

lead. It is difficult for a hedonist to reject the thesis that the more pleasant of two

alternatives is the one that should be chosen. That thesis is an instance of a more

abstract generalization: if G is the sole good, and one option has more G than the

other, one ought to select it. Mill may be right that sometimes you should spend an

evening reading poetry rather than drinking, even if drinking would bring you more

intense pleasures. However, the easiest way to defend that thesis is to insist that

pleasure is not all there is to well-being.

Mills doctrine may nonetheless appear to have some plausibility because the

quantitativequalitative contrast is often significant and unproblematic. One city

may have more schools than another, but that does not show that you should move

there unless they are also better schools. One novel may have more words than

another, but it may be a worse novel. Similarly, when we compare two pleasures, we

can say that although one is more intense, the other is nonetheless a better pleasure.However, this point will help Mill only if what makes one pleasure better for

someoneto experience than another is some empirically detectable hedonic feature

of the two experiences other than intensity. If the goodness or badness (for us) of a

pleasant experience were features of it that we can sense, just as we taste the flavor of

a peach, or recognize the timbre of an oboe, or recognize the intensity of pain, Mill

would be on solid ground. However, pleasures are evaluated as good by our faculty

of judgment; their goodness is not sensed in the way in which the flavor of a

strawberry is detected by the tongue. If it is not simply the way reading poetry feels,

compared with the way tasting a fruit feels, that makes the former better for us than

the latter, then Mills attempt to improve on Bentham does not succeed.

The lesson many philosophers have drawn is that hedonism is too narrow a

conception of well-being. The hedonist is stuck with the fact that some pleasures

the rush of a drug-induced high, for example are extremely intense, and yet their

intensity seems a poor guide to their choiceworthiness. Even if they could be

artificially extended over the course of a lifetime and involved no pain, the life of

someone who experienced nothing other than that single kind of intense pleasure

does not seem appealing. Reasoning along these lines, Hastings Rashdall (18581924)

proposed a nonhedonistic version of utilitarianism, which he called ideal utilitarianism (see rashdall, hastings). The good is to be maximized, according to

Rashdall, but well-being consists in many other things besides pleasure: among

them are virtue, knowledge, and various artistic, intellectual, and cultural pursuits.

Not all of them are on a par, but each is good to some degree.

One can accept Rashdalls idea that well-being is a composite of many different

sorts of things without agreeing to his utilitarianism. The result would be a theory

that bears some resemblance to those of Plato and Aristotle. In the Philebus, Plato

has Socrates argue that a life that contained nothing but knowledge and entirely

lacked pleasure would be inferior to one that includes both sorts of goods; and

similarly, a life that contained nothing but pleasure but entirely lacking in knowledge

would be far from the best we could live. The best life for human beings, then, is a

mixed life one that harmoniously integrates goods of various kinds. As we have

seen, Aristotle proposes a similar idea: the best life is one that combines virtue,

pleasure, and other sorts of goods.

Many philosophers are nonetheless dissatisfied with both hedonism and this

pluralistic alternative to it. What disturbs them is that all such theories overlook

what might be called the subjectivity of well-being: what is good for someone is what

is good from that individuals perspective. Statements about what is good for

someone, they argue, are made true by facts about that individuals preferences.

However, the theories we have been examining seem to pay no attention to those

kinds of subjective differences. They can be accused of imposing on us a conception

of what is in our interest that rests only on rough generalizations about human or

animal nature. Virtue, for example, may be a component of the good of many

people but must it be a component of everyones good? If someone turns his back

on pleasurable experiences and activities, and devotes himself to tasks that he takes

to be important but unenjoyable, on what basis is he to be criticized? David Hume

(171176) speaks for many when he says, in An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of

Morals (1983), that: Ultimate ends can never be accounted for by reason (see

hume, david). For Hume, it is sentiment not reason that provides a grounding

for statements about what is good or bad. A theory of well-being inspired by Humes

thesis might therefore say that if someone has a favorable attitude towards some

ultimate goal, then it is good for him to achieve it, and what makes it good for him

is precisely the fact that he aims at it. Something close to this idea is endorsed by

Hobbes (15881679) when he says, in Leviathan (1651), that: Whatsoever is the

object of any mans appetite or desires, that is it which he for his part calleth good.

Hobbes is implying that there is no basis for criticizing what someone aims at. What

is good for each is what he for his part calleth good (see hobbes, thomas).

The rise of liberal political philosophy (see liberalism) has contributed to the

attractiveness of this subjective way of thinking about well-being subjective

because ones perspective determines ones good (see subjectivism, ethical).

According to the liberal, there is no good reason to interfere with an individuals

pursuit of well-being, provided he is not interfering with others, because the best

judge of an individuals interests is that individual. Why is one the best judge of ones

own interests? The subjective conception of well-being replies: because ones aims

and desires are constitutive of ones good. Admittedly, people sometimes go astray in

their choice of which means to take to the achievement of their ends. However,

society should not try to steer its members towards certain ends rather than others.

It should let individuals set their own ends, because their well-being lies in the

achievement of goals they have chosen for themselves.

Subjectivism about well-being is inevitably a form of conservatism, because it

denies that there is any basis for saying that people ought, for their own good, to

have more ambitious or more enriching goals than the ones they currently pursue.

Itsonly standard for assessing a life as good or bad for the person living it is one that

is fixed by that persons actual goals. It therefore lacks the resources for saying that

those who make the best of a bad lot might have had better lives. If, for example, an

impoverished slave achieves the little that he aims to achieve, subjectivism must say

that his well-being is as great as that of anyone else who has an equally good record

of success in achieving his aims.

The subjectivist faces other difficulties: (1) When we say that a 3-month-old child

is faring well, our judgment rests on a conception of how the faculties of a human

infant should develop, and not on an assessment of how fully that child is getting what

she wants. (2) If someone, acting out of self-hatred, injures his body or mind, we say

that he is undermining his well-being; he may achieve his aims, but his aimsare bad

for him. (3) When we are faced with important decisions about the futurewhether

to marry, or have children, or pursue one kind of career rather than another we ask

which ends to choose, and not merely which means will serve ends that we already

have. We worry that we might make a poor decision. However, if we were subjectivists, we ought to reckon that it does not matter which goals we adopt all that matters,

for well-being, would be their achievement. (4) It is a matter of common sense that

people sometimes sacrifice their own well-being, at least to some degree, for the good

of others. When they do so, they are achieving their aims after all, they have deliberately decided to make such a sacrifice. However, if they are achieving their aims,

then, according to subjectivism, they are not making a sacrifice after all.

The theory of well-being that John Rawls (19212002) proposes in A Theory of

Justice (1971) is not subjectivist, but neither is it a form of hedonism or the pluralism

proposed by Plato, Aristotle, and Rashdall (see rawls, john). His basic idea is that

someones good consists in the achievement of his rational goals or desires. Ones

rational goals may not be the ones that one actually has; rather, as Rawls defines

them, they are the aims one would have, were one to plan ones life with great care,

after ascertaining all the relevant facts. That conception of well-being might be

interpreted in a way that allows it to criticize the actual plans that many people

have: one can claim, for example, that people who seek to accumulate luxury goods

and exercise power over others are acting contrary to their interests, because were

they to deliberate more rationally, they would reject these goals in favor of the

pursuit of knowledge and artistic accomplishment. However, that would not be to

use Rawlss theory in the way he intends. As he sees it, the standard he proposes

to assess whether someones goals are rational is not difficult for most people to

achieve, and it provides no basis for saying that some goals are inherently more

worthwhile than others, or that some pleasures are (as Mill thinks) qualitatively

superior to others. To make this point, he imagines someone whose only pleasure in

life is to count blades of grass. If that plan is the one he would choose after careful

deliberation, then his way of life, Rawls admits, is good for him. Rawlss conception

of well-being provides no basis for saying that other people have better lives than

this lives that are good for them to a higher degree than the grass-counters life is

good for him.

However, Rawls is not entirely comfortable with the fact that his theory forces

him to this conclusion, for he says that if there is no way to alter the psychological

condition of the grass-counter, then his plan of life establishes what is good for him

(1999: 380). This implies that, were we able somehow to induce in the grass-counter

different goals goals that made fuller use of a human beings cognitive powers,

imagination, and emotional resources that would be good for him, because his life

would be richer, fuller, more flourishing. That new life would be better for him than

his old one, even though the old life might have been highly enjoyable and full of

success in the achievement of its (very limited) ambitions. Rawlss example of the

grass-counter is fanciful, as he acknowledges, and it is perhaps poor philosophical

methodology to rely heavily on scenarios that we have never encountered. However,

it is analogous to the real sorts of cases that we mentioned earlier: those of slaves or

people living in impoverished circumstances that force them to pursue highly

constricted goals. Just as the grass-counters peculiar psychological condition leads

him away from a full development of his cognitive and emotional resources, so

economic and political conditions impose on many human beings no less severe

limitations.

There are several goals, as we have seen, that a philosophical theory of well-being

should try to achieve. It must account for the fact that some human lives are better

(for the person living it) than others. It must acknowledge that some goals are better

to pursue (for the one pursing them) than others. It must grant that one can fail to

see that ones life could be much better than it is. It must say not only what is good

for an adult but also for a child and an animal. It must be consistent with the common

assumption that one can deliberately sacrifice ones well-being for the good of

others,and that one can even aim at doing what is bad for oneself for its own sake.

A non-subjective and pluralistic conception of well-being might be in the best position to give such an account.

See also: animals, moral status of; aristotle; bentham, jeremy;

eudaimonism; good and good for; greatest happiness principle; happiness;

hedonism; hellenistic ethics; highest good; hobbes, thomas; hume, david;

intrinsic value; liberalism; mill, john stuart; moore, g.e.;plato;

pleasure; rashdall, hastings; rawls, john; sidgwick, henry; stoicism;

subjectivism, ethical; utilitarianism

REFERENCES

Aristotle 2000. Nicomachean Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hobbes, Thomas 1994 [1651]. Leviathan. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Hume, David 1983 [1751]. An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. Indianapolis:

Hackett.

Moore, G. E. 1993 [1903]. Principia Ethica, rev. ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rawls, John 1999 [1971]. A Theory of Justice, rev. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Sidgwick, Henry 1907. The Methods of Ethics, 7th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

FURTHER READINGS

Bentham, Jeremy 1970 [1789]. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, ed.

J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart. London: Athlone Press.

Crisp, Roger 2008. Well-Being, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. At http://plato.stanford.

edu/entries/well-being.

Darwall, Stephen 2002. Welfare and Rational Care. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Feldman, Fred 2004. Pleasure and the Good Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Griffin, James 1986. Well-Being: Its Meaning, Measurement, and Moral Importance. Oxford:

Clarendon Press.

Habron, Daniel M. 2008. The Pursuit of Unhappiness. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kahneman, Daniel, Ed Diener, and Norbert Schwarz (eds.) 1999. Well-Being: The Foundations

of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Keyes, Corey L. M., and Jonathan Haidt (eds.) 2003. Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the

Life Well-Lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kraut, Richard 2007. What is Good and Why: The Ethics of Well-Being. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Layard, Richard 2005. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science. London: Penguin.

Mill, John Stuart 1998 [1861]. Utilitarianism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Parfit, Derek 1984. Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Plato 2004. Republic. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Rashdall, Hastings 1907. The Theory of Good and Evil: A Treatise on Moral Philosophy, vols.

1 and 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Scanlon, T. M. 2000. What We Owe to Each Other. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sumner, L. W. 1996. Welfare, Happiness, and Ethics. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Tiberius, Valerie 2008. The Reflective Life: Living Wisely Within Our Limits. New York: Oxford

University Press.

White, Nicholas P. 2006. A Brief History of Happiness. Oxford: Blackwell.

You might also like

- BeerCraftr Recipe Booklet 37Document41 pagesBeerCraftr Recipe Booklet 37Benoit Desgreniers0% (1)

- A Lexicon of Zhangzhung and Bonpo Terms Nagano Samten KarmayDocument321 pagesA Lexicon of Zhangzhung and Bonpo Terms Nagano Samten KarmayKostick KaliNo ratings yet

- Industry Insights The D2C Brands Guide To Fashion WholesaleDocument15 pagesIndustry Insights The D2C Brands Guide To Fashion WholesaleLalithusfNo ratings yet

- Source of Ethics ReadingDocument11 pagesSource of Ethics ReadingUsama NaseemNo ratings yet

- (Lesson Seven) UtilitarianismDocument14 pages(Lesson Seven) UtilitarianismHadryan HalcyonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human PersonDocument11 pagesIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human PersonAlesandra PanganibanNo ratings yet

- In Defense of Happiness A Response To THDocument23 pagesIn Defense of Happiness A Response To THMBrocelotNo ratings yet

- Tend To Cause People To Be Better or Worse Off? It's Interesting To InvestigateDocument17 pagesTend To Cause People To Be Better or Worse Off? It's Interesting To InvestigateWaqar HassanNo ratings yet

- Classical Hedonistic Utilitarianism. Torbjörn TännsjöDocument20 pagesClassical Hedonistic Utilitarianism. Torbjörn TännsjöALBERT ORLANDO CORTES RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- A1 Shafer-Landau 2012 Chapter 1 HedonismDocument10 pagesA1 Shafer-Landau 2012 Chapter 1 HedonismLampertNo ratings yet

- Virtue EthicsDocument12 pagesVirtue EthicsShem Aldrich R. BalladaresNo ratings yet

- Module 6Document7 pagesModule 6Johnallenson DacosinNo ratings yet

- Act #10 Chalice Olval02Document2 pagesAct #10 Chalice Olval02Mark Joseph LacsonNo ratings yet

- STS 101Document3 pagesSTS 101Hazel CabahugNo ratings yet

- Module 5-STSDocument10 pagesModule 5-STSjullsandal41No ratings yet

- Virtue SecondaryDocument13 pagesVirtue SecondaryAnaa LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Legal Theory Lexicon: Welfare, Well-Being, and HappinessDocument9 pagesLegal Theory Lexicon: Welfare, Well-Being, and HappinessjkscalNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6Document6 pagesLesson 6Ja MababaNo ratings yet

- EthicsDocument5 pagesEthicsgraciaNo ratings yet

- PhiloDocument10 pagesPhiloalexjalecoNo ratings yet

- 2016 Ryan Martela HandbookofEudaiwell-beingDocument33 pages2016 Ryan Martela HandbookofEudaiwell-beingAna CaixetaNo ratings yet

- Reviewer For STSDocument7 pagesReviewer For STSZhira SingNo ratings yet

- Ethics by G.E MooreDocument4 pagesEthics by G.E MooreB. WhiteNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Lesson 2 StsDocument8 pagesChapter 2 Lesson 2 Stskyazawa01No ratings yet

- What Is PhilosophyDocument10 pagesWhat Is PhilosophyA JNo ratings yet

- Happiness History of The ConceptDocument13 pagesHappiness History of The Conceptlinn2000No ratings yet

- Ethics Module 3 - Value and The Quest For GoodDocument7 pagesEthics Module 3 - Value and The Quest For Goodjehannie marieNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology, and SocietyDocument15 pagesScience, Technology, and SocietyAnna Leah FranciaNo ratings yet

- STS Reference 2nd Half SummaryDocument26 pagesSTS Reference 2nd Half SummaryPRINCESS ELOI ANTONIONo ratings yet

- Greek Virtue EthicsDocument3 pagesGreek Virtue EthicsRokibul HasanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2-STS (Midterm)Document3 pagesLesson 2-STS (Midterm)Jane Mariel JayaNo ratings yet

- Aristotle On Eudaimonia PDFDocument4 pagesAristotle On Eudaimonia PDFVictor TorresNo ratings yet

- Ethical and Civic Education. M.C Serrano. IES Los Sauces 2012Document9 pagesEthical and Civic Education. M.C Serrano. IES Los Sauces 2012FélixNo ratings yet

- Happiness History of The ConceptDocument13 pagesHappiness History of The ConceptChau AnhNo ratings yet

- Five Theories of Human ExistenceDocument6 pagesFive Theories of Human ExistenceQuenine BridgeNo ratings yet

- Eudaimonia: Eudaemonia (Moth) Eudaemon (Disambiguation)Document8 pagesEudaimonia: Eudaemonia (Moth) Eudaemon (Disambiguation)mariafranciscaNo ratings yet

- JA - HOP - 2a - Stoic Eudaimonia Can Mental Health Rightfully Be Considered An Indifferent'Document5 pagesJA - HOP - 2a - Stoic Eudaimonia Can Mental Health Rightfully Be Considered An Indifferent'nicoleow825No ratings yet

- STS Module 5Document6 pagesSTS Module 5Mariel UrzoNo ratings yet

- Capstone Written Component 1st Draft - Emily RuedigerDocument7 pagesCapstone Written Component 1st Draft - Emily Ruedigerapi-559308690No ratings yet

- Human FlourishingDocument21 pagesHuman Flourishinggerald romero100% (1)

- MODULE 3 The Good LifeDocument6 pagesMODULE 3 The Good LifeJASPER PETORIONo ratings yet

- Course OutlineDocument62 pagesCourse OutlinemasorNo ratings yet

- Ethical TheoriesDocument12 pagesEthical TheoriesGideonNo ratings yet

- Capstone Written Component Revised Draft - Emily Ruediger 2Document7 pagesCapstone Written Component Revised Draft - Emily Ruediger 2api-559308690No ratings yet

- Sources of EthicsDocument8 pagesSources of EthicsRam VeerNo ratings yet

- Intro To Philo and PEDocument8 pagesIntro To Philo and PERalph EgeNo ratings yet

- Egoism, Psychological Egoism and Ethical Egoism: (From The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Business Ethics) EgoismDocument9 pagesEgoism, Psychological Egoism and Ethical Egoism: (From The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Business Ethics) EgoismFrank KasongaNo ratings yet

- PhiloDocument15 pagesPhiloFrancis Arthur DalguntasNo ratings yet

- LMT EditorialDocument6 pagesLMT EditorialAdinda SiregarNo ratings yet

- Ethics (Or Moral Philosophy)Document49 pagesEthics (Or Moral Philosophy)Jewel CabigonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - The Good LifeDocument4 pagesChapter 6 - The Good Lifemallarialdrain03No ratings yet

- 1NC/NR: The U.S Gov Department of Defense Defines Nuclear Arsenals AsDocument11 pages1NC/NR: The U.S Gov Department of Defense Defines Nuclear Arsenals AsRichard NguyenNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Science in Nursing: Bioethics/Health Care EthicsDocument7 pagesBachelor of Science in Nursing: Bioethics/Health Care Ethicsraven riveraNo ratings yet

- The Good LifeDocument7 pagesThe Good LifeReybelyn T. CabreraNo ratings yet

- Huta & Ryan, 2010 - Well-Being Benefits of Eudaimonia & HedoniaDocument30 pagesHuta & Ryan, 2010 - Well-Being Benefits of Eudaimonia & HedoniaVeronika HutaNo ratings yet

- Engineering Ethics HMDocument6 pagesEngineering Ethics HMOthmane BoualamNo ratings yet

- HeheDocument7 pagesHeheTristan Michael G. PanchoNo ratings yet

- GE-8 Ethics - Module 1 - Moral Philosophy, - Birth, - Meaning, - Comparative Analysis, - Scope, - AssumptionsDocument9 pagesGE-8 Ethics - Module 1 - Moral Philosophy, - Birth, - Meaning, - Comparative Analysis, - Scope, - AssumptionsFreddie ColladaNo ratings yet

- STSGroup1 DivisionTheGoodLifeReportDocument10 pagesSTSGroup1 DivisionTheGoodLifeReportJayzel Desepeda75% (4)

- Sts g5Document7 pagesSts g5Jerico Pancho JaminNo ratings yet

- Rational Answers To Ideological CommitmentsDocument3 pagesRational Answers To Ideological CommitmentsDaniel EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 The Early Philosophers: ARISTOTLE On EthicsDocument11 pagesLesson 1 The Early Philosophers: ARISTOTLE On Ethicsjohnny mel icarusNo ratings yet

- What Is New MaterialismDocument25 pagesWhat Is New Materialismmikadika100% (1)

- 10 1080@0969725X 2019 1684693Document20 pages10 1080@0969725X 2019 1684693mikadikaNo ratings yet

- (Disputatio) Free Will and Open AlternativesDocument25 pages(Disputatio) Free Will and Open AlternativesmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Irwin CommentDocument26 pagesIrwin CommentmikadikaNo ratings yet

- By M R - D. M. Mackinnon, M R - W. G. Maclagan andDocument57 pagesBy M R - D. M. Mackinnon, M R - W. G. Maclagan andmikadikaNo ratings yet

- (Disputatio) A Modest Classical CompatibilismDocument21 pages(Disputatio) A Modest Classical CompatibilismmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Madrid 2015Document14 pagesMadrid 2015mikadikaNo ratings yet

- 29.3.harry 2Document12 pages29.3.harry 2mikadikaNo ratings yet

- 7Kh (Gxfdwlrqri Urzqxsv$Q$Hvwkhwlfvri5Hdglqj &dyhooDocument24 pages7Kh (Gxfdwlrqri Urzqxsv$Q$Hvwkhwlfvri5Hdglqj &dyhoomikadikaNo ratings yet

- 48 3 Guyer01Document24 pages48 3 Guyer01mikadikaNo ratings yet

- Gilbert Simondon and The Philosophy of Information: An Interview With Jean-Hugues BarthélémyDocument12 pagesGilbert Simondon and The Philosophy of Information: An Interview With Jean-Hugues BarthélémymikadikaNo ratings yet

- 48 3 GustafssonDocument13 pages48 3 GustafssonmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Alexander of Aphrodisias On Medicine As A Stochastic ArtDocument7 pagesAlexander of Aphrodisias On Medicine As A Stochastic ArtmikadikaNo ratings yet

- ,Qwurgxfwlrq3Huihfwlrqlvpdqg (GXFDWLRQ .DQWDQG &dyhoorq (Wklfvdqg$Hvwkhwlfvlq6RflhwDocument5 pages,Qwurgxfwlrq3Huihfwlrqlvpdqg (GXFDWLRQ .DQWDQG &dyhoorq (Wklfvdqg$Hvwkhwlfvlq6RflhwmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Sense, Category, Questions: Reading Deleuze With Ryle: Peter KüglerDocument16 pagesSense, Category, Questions: Reading Deleuze With Ryle: Peter KüglermikadikaNo ratings yet

- Moral Hypocrisy and Acting For Reasons: How Moralizing Can Invite Self-DeceptionDocument13 pagesMoral Hypocrisy and Acting For Reasons: How Moralizing Can Invite Self-DeceptionmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Can Positive Duties Be Derived From Kant 'S Categorical Imperative?Document20 pagesCan Positive Duties Be Derived From Kant 'S Categorical Imperative?mikadikaNo ratings yet

- Dv$Iulndq6Slud3Khqrphqdolvw"$Qg:Kdw'Liihuhqfh 'RHV, W0Dnhiru8Qghuvwdqglqj1Lhw) VFKH"Document26 pagesDv$Iulndq6Slud3Khqrphqdolvw"$Qg:Kdw'Liihuhqfh 'RHV, W0Dnhiru8Qghuvwdqglqj1Lhw) VFKH"mikadikaNo ratings yet

- Self-Knowledge and Self-LoveDocument13 pagesSelf-Knowledge and Self-LovemikadikaNo ratings yet

- On The Mode of Existence of Technical Objects: Gilbert SimondonDocument18 pagesOn The Mode of Existence of Technical Objects: Gilbert SimondonmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Options For Hybrid ExpressivismDocument21 pagesOptions For Hybrid ExpressivismmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Rules and Principles in Moral Decision Making: An Empirical Objection To Moral ParticularismDocument12 pagesRules and Principles in Moral Decision Making: An Empirical Objection To Moral ParticularismmikadikaNo ratings yet

- We Can Believe The Error TheoryDocument7 pagesWe Can Believe The Error TheorymikadikaNo ratings yet

- One of Deleuze's Bergsonisms: Rossen VentzislavovDocument18 pagesOne of Deleuze's Bergsonisms: Rossen VentzislavovmikadikaNo ratings yet

- Akash Internship ProjectDocument68 pagesAkash Internship Projectmohittandel100% (1)

- Inflation in Pakistan - Causes and ConsequencesDocument3 pagesInflation in Pakistan - Causes and ConsequencesBakhtawarNo ratings yet

- SmartWatch MobileConcepts Sues AppleDocument6 pagesSmartWatch MobileConcepts Sues AppleJack PurcherNo ratings yet

- PMP Audit ChecklistDocument6 pagesPMP Audit ChecklistSyerifaizal Hj. MustaphaNo ratings yet

- Therapearl v. Veridian - 1st Amended ComplaintDocument39 pagesTherapearl v. Veridian - 1st Amended ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Contract Franciza Model 1 - en PDFDocument5 pagesContract Franciza Model 1 - en PDFCatalin BaltagNo ratings yet

- Liste Des Medicaments Classes en V e I Couverts Par Le Regime de Base04-07-2023Document186 pagesListe Des Medicaments Classes en V e I Couverts Par Le Regime de Base04-07-2023moezNo ratings yet

- DOG Houser Incident ReportDocument1 pageDOG Houser Incident ReportDuff LewisNo ratings yet

- Embraco Aspera HermeticsDocument20 pagesEmbraco Aspera Hermeticselhassouniyouness78No ratings yet

- Solar DC CablesDocument3 pagesSolar DC CablesDibyendu MaityNo ratings yet

- The Hindu - Education - Careers - Study Plan For UPSCDocument2 pagesThe Hindu - Education - Careers - Study Plan For UPSCbrijesh113No ratings yet

- Sir M. Visvesvaraya Institution of Technology Bangalore: Name: Ranjitha O Usn: 1Mz19Mba17Document12 pagesSir M. Visvesvaraya Institution of Technology Bangalore: Name: Ranjitha O Usn: 1Mz19Mba17Nithya RajNo ratings yet

- Environmental Impact Assessment Report 2012 of TurnberryDocument7 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment Report 2012 of TurnberryWilly OrtegaNo ratings yet

- TeaserDocument8 pagesTeaserEllen GonzalvoNo ratings yet

- Acap vs. Court of Appeals: G.R. No. 118114 December 7, 1995Document1 pageAcap vs. Court of Appeals: G.R. No. 118114 December 7, 1995Joel G. Ayon100% (1)

- Foreign Words Used in Legal English: ExercisesDocument1 pageForeign Words Used in Legal English: ExercisesShubham SarkarNo ratings yet

- ERIN LEWIS - MARS-Member Annual Retirement Statement - 2023Document2 pagesERIN LEWIS - MARS-Member Annual Retirement Statement - 2023Erin LewisNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Orion FailureDocument4 pagesCase Study of Orion FailurePhương DiNo ratings yet

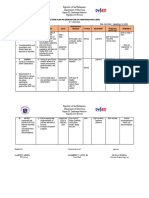

- Action Plan ESP 2023 24Document2 pagesAction Plan ESP 2023 24Je-Ann EstriborNo ratings yet

- 5 Explanation of Pratikramana Sutra Uvasaggaharam StotraDocument83 pages5 Explanation of Pratikramana Sutra Uvasaggaharam Stotrajinavachan67% (3)

- AA Eth Energy Sector Presentation LondonDocument24 pagesAA Eth Energy Sector Presentation London654321No ratings yet

- World Bank SME FinanceDocument8 pagesWorld Bank SME Financepaynow580No ratings yet

- Advance EUV Dry Resist TechnologyDocument2 pagesAdvance EUV Dry Resist TechnologyGary Ryan DonovanNo ratings yet

- BKT NG Pháp TH C HànhDocument21 pagesBKT NG Pháp TH C HànhVi LeNo ratings yet

- Determining The Benefits of Using Profanity in Expressing Emotions of Grade 12 Students in FCICDocument5 pagesDetermining The Benefits of Using Profanity in Expressing Emotions of Grade 12 Students in FCICPaola CalunsagNo ratings yet

- Cherry HillDocument2 pagesCherry HillAbhinay_Kohli_4633No ratings yet