Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Disparity and Diversity

Uploaded by

Ardibel VillanuevaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Disparity and Diversity

Uploaded by

Ardibel VillanuevaCopyright:

Available Formats

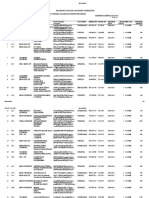

Disparity and Diversity 55

bilaterian body plan is not fixed once in place. We will see in chapter 5

that there might be something to the idea that body plans, once they

evolve, are stabilized and become difficult to change. This idea is an

important theme of Bill Wimsatt’s work (see Wimsatt 2007). But this

idea of stabilization does not show there is anything special about phyla,

about, say, the arthropod rather than the trilobite body plan. The body

organizations we take to be distinctive of the metazoan phyla are not

especially, uniquely stabilized. A phylum is a large monophyletic chunk

of the tree of animal life, and the organisms in a phylum will resemble

one another in various ways due to their shared deep ancestry. To be

told that a biota includes representatives from, say, the arthropods, mol-

lusks, and bivalves is to be given useful information (in contrast, say,

to being told that it contains organisms used in Wiccan spells). But

phyla are not objectively countable units. After all, the idea of a body

plan is fundamentally hierarchical. Cephalopods are mollusks. There is

a cephalopod body plan, and a mollusk body plan, and the first is a ver-

sion of the second. But there is nothing objective that determines which

of these organizations, if either, characterizes a phylum.

So we should be cautious about inferring phenotypic disparity from

traditional taxonomy. We should be especially cautious if the animals

are ancient. This new phylogeny shows how the Cambrian fauna can be

integrated within the tree of life, and this integration predicts that the

Cambrian fauna would seem to be very disparate, even if it were not.

The crucial distinction is between the stem and the crown members of

a lineage. This distinction is best explained through an example, and

we will borrow Andrew Knoll’s example of the divergence between the

arthropods and their (possible) sister phylum, nematodes (Knoll 2003,

187–90). These are both members of the Ecdysozoa, so they share the

molting cuticle characteristic of that clade as well as its genetic and

developmental signatures, but apparently not much else. Arthropods

are segmented, with jointed appendages and an external skeleton made

from chitin. Nematodes are a species-rich clade of tiny worms, tapered

at both ends. The joint ancestor of this clade—their last common

ancestor—would have resembled neither. It would not have possessed

the distinctive suite of arthropod characteristics, but neither would it

have had the radically simplified anatomy (compared to many bilateria)

of the nematodes. So consider the evolutionary history of the arthropod

lineage leading from this last common ancestor to crustaceans, insects,

and spiders. On this lineage the distinctive characteristics that unite the

arthropods—segmentation, chitinous skeleton, jointed appendages—

would have evolved. But not all at once. Perhaps the order was chitin,

then segmented body, then jointed appendages.

You might also like

- Classification Lecturetutorial Material 2023Document15 pagesClassification Lecturetutorial Material 2023이승빈No ratings yet

- Chapter 20 Phylogeny (AP Biology Notes)Document5 pagesChapter 20 Phylogeny (AP Biology Notes)LeAnnNo ratings yet

- The Completely Different World of Protists - Biology Book for Kids | Children's Biology BooksFrom EverandThe Completely Different World of Protists - Biology Book for Kids | Children's Biology BooksNo ratings yet

- Understanding Phylogenies: The DefinitionDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Phylogenies: The DefinitionShikure ChanNo ratings yet

- Evolution: What Darwin Did Not Know by Then..! [And the Origin of Species Through Species-Branding]From EverandEvolution: What Darwin Did Not Know by Then..! [And the Origin of Species Through Species-Branding]No ratings yet

- 9-10 Cassification of Living ThingsDocument9 pages9-10 Cassification of Living ThingsDesi Aziya FitriNo ratings yet

- UE - Building The TreeDocument1 pageUE - Building The Treeskline3No ratings yet

- Phylogenetic SystematicsDocument6 pagesPhylogenetic SystematicsSakshi IssarNo ratings yet

- Species As Individuals: Biology and PhilosophyDocument20 pagesSpecies As Individuals: Biology and PhilosophyPhilippeGagnonNo ratings yet

- Discuss TaxonomyDocument4 pagesDiscuss TaxonomyAlyssa AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Phylogeny The Tree of Life Myp Class LectureDocument46 pagesPhylogeny The Tree of Life Myp Class LectureSamar El-MalahNo ratings yet

- 4 Biodiversity and ClassificationDocument2 pages4 Biodiversity and ClassificationntambiNo ratings yet

- Evidence of Evolution FinalDocument82 pagesEvidence of Evolution FinalCheskaNo ratings yet

- Science LayoutDocument2 pagesScience LayoutGillian OpolentisimaNo ratings yet

- Taxonomy ReviwerDocument12 pagesTaxonomy ReviwersnaollhatNo ratings yet

- Similarity Is Not Enough: 14 Chapter OneDocument1 pageSimilarity Is Not Enough: 14 Chapter OneArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Systematics and PhylogenyDocument5 pagesSystematics and PhylogenyBryan FabroNo ratings yet

- Evolution 101: The History of Life: Looking at The PatternsDocument16 pagesEvolution 101: The History of Life: Looking at The PatternsMinnhela Gwen MarcosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 7 Zoology Learning ModuleDocument38 pagesLesson 5 7 Zoology Learning ModuleAnde Falcone AlbiorNo ratings yet

- BASIC BIOLOGY NOTES Sem 1 Part 1Document4 pagesBASIC BIOLOGY NOTES Sem 1 Part 1Polee SheaNo ratings yet

- Bio Module 2 PhotoMasterDocument23 pagesBio Module 2 PhotoMasterh33% (3)

- Principles of Classification of Living ThingsDocument5 pagesPrinciples of Classification of Living ThingsHey UserNo ratings yet

- Evidences of Evolution Module 6-7Document47 pagesEvidences of Evolution Module 6-7GLAIZA CALVARIONo ratings yet

- Our Common Insects: A Popular Account of the Insects of Our Fields, Forests, Gardens and HousesFrom EverandOur Common Insects: A Popular Account of the Insects of Our Fields, Forests, Gardens and HousesNo ratings yet

- Symmetry in Evolution: by Phillip L. EngleDocument36 pagesSymmetry in Evolution: by Phillip L. EngleMok Pey WengNo ratings yet

- The Biological Problem of To-day: Preformation Or Epigenesis?: The Basis of a Theory of Organic DevelopmentFrom EverandThe Biological Problem of To-day: Preformation Or Epigenesis?: The Basis of a Theory of Organic DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- The Theory and Practice of Breeding to Type and Its Application to the Breeding of Dogs, Farm Animals, Cage Birds and Other Small PetsFrom EverandThe Theory and Practice of Breeding to Type and Its Application to the Breeding of Dogs, Farm Animals, Cage Birds and Other Small PetsNo ratings yet

- Topic1 BIOL1030NRDocument7 pagesTopic1 BIOL1030NRsenjicsNo ratings yet

- CH5 - Lesson 16 The Process of Evolution PDFDocument5 pagesCH5 - Lesson 16 The Process of Evolution PDFgwynethNo ratings yet

- Taboo and Genetics: A Study of the Biological, Sociological and Psychological Foundation of the FamilyFrom EverandTaboo and Genetics: A Study of the Biological, Sociological and Psychological Foundation of the FamilyNo ratings yet

- The Development of Philosophy of SpeciesDocument80 pagesThe Development of Philosophy of SpeciesDFNo ratings yet

- Phylogenrtictree Mode 2Document27 pagesPhylogenrtictree Mode 2ASUTOSH MISHRANo ratings yet

- Evolution LabDocument13 pagesEvolution LabCatostylusmosaicus100% (1)

- Phylum - WikipediaDocument9 pagesPhylum - WikipediakoiNo ratings yet

- Camp's Zoology by the Numbers: A comprehensive study guide in outline form for advanced biology courses, including AP, IB, DE, and college courses.From EverandCamp's Zoology by the Numbers: A comprehensive study guide in outline form for advanced biology courses, including AP, IB, DE, and college courses.No ratings yet

- EVOLUTIONDocument15 pagesEVOLUTIONKiama GitahiNo ratings yet

- Animal: OrganismDocument22 pagesAnimal: OrganismWraith WrathNo ratings yet

- Fundamental of Biology: Living and Non-LivingDocument12 pagesFundamental of Biology: Living and Non-LivingSanthi VardhanNo ratings yet

- Evolution 101Document102 pagesEvolution 101IWantToBelieve8728100% (2)

- Evidence For Evolution Factsheet v2Document5 pagesEvidence For Evolution Factsheet v2api-364379734No ratings yet

- Cassification of Living ThingsDocument11 pagesCassification of Living ThingsFidia Diah AyuniNo ratings yet

- LAB 21 - Evolution and ClassificationDocument13 pagesLAB 21 - Evolution and ClassificationMary Vienne PascualNo ratings yet

- Bio NotesDocument48 pagesBio NotesNaimah RaiNo ratings yet

- Mbizzarri,+7 1 OrigArt Atavism HuangDocument22 pagesMbizzarri,+7 1 OrigArt Atavism HuangbaliardoforcaNo ratings yet

- Species and SpeciationDocument27 pagesSpecies and Speciationjay cNo ratings yet

- Zoology 1Document4 pagesZoology 1Jheza HuillerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 25 OutlineDocument11 pagesChapter 25 OutlineEvelyn KimNo ratings yet

- Lesson 13: Evolutionary Relationship of OrganismDocument13 pagesLesson 13: Evolutionary Relationship of OrganismArnio SaludarioNo ratings yet

- Ontogenia Fósil INGDocument17 pagesOntogenia Fósil INGUriel RodríguezNo ratings yet

- 80 Chapter FourDocument1 page80 Chapter FourArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument1 pagePDFArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 78 Chapter FourDocument1 page78 Chapter FourArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 72 Chapter FourDocument1 page72 Chapter FourArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 74 Chapter FourDocument1 page74 Chapter FourArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument1 pagePDFArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Geometry of Evolution (2006), George Mcghee Makes A Strong Case ForDocument1 pageGeometry of Evolution (2006), George Mcghee Makes A Strong Case ForArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 68 Chapter FourDocument1 page68 Chapter FourArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument1 pagePDFArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument1 pagePDFArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument1 pagePDFArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 50 Chapter ThreeDocument1 page50 Chapter ThreeArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 52 Chapter ThreeDocument1 page52 Chapter ThreeArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument1 pagePDFArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 64 Chapter FourDocument1 page64 Chapter FourArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Morphology and Morphological DiversityDocument1 pageMorphology and Morphological DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Awkwardness To Suppose That Cambrian Fauna Were Unusually Disparate?Document1 pageAwkwardness To Suppose That Cambrian Fauna Were Unusually Disparate?Ardibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- 54 Chapter ThreeDocument1 page54 Chapter ThreeArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Binia Were Still Living, We Would Have A Diff Erent and More InclusiveDocument1 pageBinia Were Still Living, We Would Have A Diff Erent and More InclusiveArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Disparity and DiversityDocument1 pageDisparity and DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Disparity and DiversityDocument1 pageDisparity and DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Disparity and DiversityDocument1 pageDisparity and DiversityArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Group Arthropods. The Identifi Cation of Nematodes As The Arthropod SisDocument1 pageGroup Arthropods. The Identifi Cation of Nematodes As The Arthropod SisArdibel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Nephrology and HypertensionDocument33 pagesNephrology and HypertensionCarlos HernándezNo ratings yet

- Animation I Syllabus 2Document3 pagesAnimation I Syllabus 2api-207924970100% (1)

- CR PPTDocument15 pagesCR PPTsamikshachandakNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Hyper Loop TrainDocument3 pagesCase Study of Hyper Loop TrainkshitijNo ratings yet

- 2021 06 WJU Circus Fanfare NOV DECDocument28 pages2021 06 WJU Circus Fanfare NOV DECDwarven SniperNo ratings yet

- 28-03-2023 Sed TicketsDocument8 pages28-03-2023 Sed TicketssureshhkNo ratings yet

- Science Camp Day 1Document13 pagesScience Camp Day 1Mariea Zhynn IvornethNo ratings yet

- Superkids 3eDocument19 pagesSuperkids 3eiin hermiyantoNo ratings yet

- Magness - The Tomb of Jesus and His Family - Exploring Ancient Jewish Tombs Near Jerusalem's Walls Book ReviewDocument5 pagesMagness - The Tomb of Jesus and His Family - Exploring Ancient Jewish Tombs Near Jerusalem's Walls Book Reviewarbg100% (1)

- Chap3 Laterally Loaded Deep FoundationDocument46 pagesChap3 Laterally Loaded Deep Foundationtadesse habtieNo ratings yet

- Week - 14, Methods To Control Trade CycleDocument15 pagesWeek - 14, Methods To Control Trade CycleMuhammad TayyabNo ratings yet

- (Socks, Shoes, Watches, Shirts, ... ) (Index, Middle, Ring, Pinky)Document7 pages(Socks, Shoes, Watches, Shirts, ... ) (Index, Middle, Ring, Pinky)Rosario RiveraNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Supervisory Report School/District: Cacawan High SchoolDocument17 pagesDepartment of Education: Supervisory Report School/District: Cacawan High SchoolMaze JasminNo ratings yet

- Scholarship ResumeDocument2 pagesScholarship Resumeapi-331459951No ratings yet

- Creative Writers and Daydreaming by Sigmund Freud To Print.Document7 pagesCreative Writers and Daydreaming by Sigmund Freud To Print.Robinhood Pandey82% (11)

- Intern CV Pheaktra TiengDocument3 pagesIntern CV Pheaktra TiengTieng PheaktraNo ratings yet

- Hindi Cinema 3rd Sem Notes PDF (2) - 1 PDFDocument37 pagesHindi Cinema 3rd Sem Notes PDF (2) - 1 PDFLateef ah malik100% (1)

- Soalan Tugasan HBMT2103 - V2 Sem Mei 2015Document10 pagesSoalan Tugasan HBMT2103 - V2 Sem Mei 2015Anonymous wgrNJjANo ratings yet

- Roman Empire Revived TheoryDocument173 pagesRoman Empire Revived TheoryBrenoliNo ratings yet

- The Achaeans (Also Called The "Argives" or "Danaans")Document3 pagesThe Achaeans (Also Called The "Argives" or "Danaans")Gian Paul JavierNo ratings yet

- Legalese and Legal EnglishDocument16 pagesLegalese and Legal English667yhNo ratings yet

- Axie Infinity Reviewer - by MhonDocument29 pagesAxie Infinity Reviewer - by MhonGodisGood AlltheTime100% (2)

- Magic Maze: Props IncludedDocument4 pagesMagic Maze: Props IncludedarneuhüdNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Foundations of American DemocracyDocument9 pagesUnit 1 - Foundations of American DemocracybanaffiferNo ratings yet

- HarshadDocument61 pagesHarshadsaurabh deshmukhNo ratings yet

- Operating BudgetDocument38 pagesOperating BudgetRidwan O'connerNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Mathematics (Honours and Regular) : Submitted ToDocument19 pagesSyllabus Mathematics (Honours and Regular) : Submitted ToDebasish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Summary Prof EdDocument19 pagesSummary Prof EdFloravie Onate100% (2)

- Escalation How Much Is Enough?Document9 pagesEscalation How Much Is Enough?ep8934100% (2)

- Antenatal Assessment of Fetal Well Being FileminimizerDocument40 pagesAntenatal Assessment of Fetal Well Being FileminimizerPranshu Prajyot 67No ratings yet

![Evolution: What Darwin Did Not Know by Then..! [And the Origin of Species Through Species-Branding]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/270231362/149x198/aea4885cd2/1677109978?v=1)