Professional Documents

Culture Documents

4 Types of Ecological Interactions

Uploaded by

King ZorCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

4 Types of Ecological Interactions

Uploaded by

King ZorCopyright:

Available Formats

Parasitism

Parasitism is a relationship in which one organism benefits and the other organism is harmed, but

not always killed. The organism that benefits is called the parasite, and the one that is harmed is

the host. Parasitism is different from parasitoidism, which is when the host is always killed, such

as when one organism lays its egg inside another organism that is later eaten by the hatchlings.

Parasites can be ectoparasites -- such as ticks, fleas, and leeches -- that live on the surface of the

host. Parasites can also be endoparasites -- such as intestinal worms – that live inside the host.

Endoparasites can be further categorized into intercellular parasites, that live in the space

between cells, or intracellular parasites, which live inside of cells. There is also something called

hyperparasitism, which is when a parasite is infected by another parasite, such as a

microorganism living in a flea, which lives on a dog. Lastly, a relationship called social

parasitism is exemplified by an ant species that does not have worker ants, living among another

ant species that do, by using the host species’ workers.

Predation: One Wins, One Loses

Predation includes any interaction between two species in which one species benefits by

obtaining resources from and to the detriment of the other. While it's most often associated with

the classic predator-prey interaction, in which one species kills and consumes another, not all

predation interactions result in the death of one organism. In the case of herbivory, a herbivore

often consumes only part of the plant. While this action may result in injury to the plant, it may

also result in seed dispersal. Many ecologists include parasitic interactions in discussions of

predation. In such relationships, the parasite causes harm to the host over time, possibly even

death. As an example, parasitic tapeworms attach themselves to the intestinal lining of dogs,

humans and other mammals, consuming partially digested food and depriving the host of

nutrients, thus lowering the host's fitness.

Competition: The Double Negative

Competition exists when multiple organisms vie for the same, limiting resource. Because the use

of a limited resource by one species decreases availability to the other, competition lowers the

fitness of both. Competition can be interspecific, between different species, or intraspecific,

between individuals of the same species. In the 1930s, Russian ecologist Georgy Gause proposed

that two species competing for the same limiting resource cannot coexist in the same place at the

same time. As a consequence, one species may be driven to extinction, or evolution reduces the

competition.

When organisms compete for a resource (such as food or building materials) it is called

consumptive or exploitative competition. When they compete for territory, it is called

interference competition. When they compete for new territory by arriving there first, it is called

preemptive competition. An example is lions and hyenas that compete for prey.

Mutualism: Everyone Wins

Mutualism describes an interaction that benefits both species. A well-known example exists in

the mutualistic relationship between alga and fungus that form lichens. The photsynthesizing

alga supplies the fungus with nutrients, and gains protection in return. The relationship also

allows lichen to colonize habitats inhospitable to either organism alone. In rare case, mutualistic

partners cheat. Some bees and birds receive food rewards without providing pollination services

in exchange. These "nectar robbers" chew a hole at the base of the flower and miss contact with

the reproductive structures.

Mutualistic interaction patterns occur in three forms. Obligate mutualism is when one species

cannot survive apart from the other. Diffusive mutualism is when one organism can live with

more than one partner. Facultative mutualism is when one species can survive on its own under

certain conditions. On top of these, mutualistic relationships have three general purposes.

Trophic mutualism is exemplified in lichens, which consist of fungi and either algae or

cyanobacteria. The fungi's partners provide sugar from photosynthesis and the fungi provide

nutrients from digesting rock. Defensive mutualism is when one organism provides protection

from predators while the other provides food or shelter: an example is ants and aphids.

Dispersive mutualism is when one species receives food in return for transporting the pollen of

the other organism, which occurs between bees and flowers.

Commensalism: A Positive/Zero Interaction

An interaction where one species benefits and the other remains unaffected is known as

commensalism. As an example, cattle egrets and brown-headed cowbirds forage in close

association with cattle and horses, feeding on insects flushed by the movement of the livestock.

The birds benefit from this relationship, but the livestock generally do not. Often it's difficult to

tease apart commensalism and mutualism. For example, if the egret or cowbird feeds on ticks or

other pests off of the animal's back, the relationship is more aptly described as mutualistic.

Another example is when an orchid is growing as an epiphyte on a mango tree gets shelter and

nutrition from mango tree, while the mango tree is neither benefitted nor harmed.

Examples are barnacles that grow on whales and other marine animals. The whale gains no

benefit from the barnacle, but the barnacles gain mobility, which helps them evade predators,

and are exposed to more diverse feeding opportunities. There are four basic types of commensal

relationships. Chemical commensalism occurs when one bacteria produces a chemical that

sustains another bacteria. Inquilinism is when one organism lives in the nest, burrow, or

dwelling place of another species. Metabiosis is commensalism in which one species is

dependent on the other for survival. Phoresy is when one organism temporarily attaches to

another organism for the purposes of transportation.

Amensalism: A Negative/Zero Interaction

Amensalism describes an interaction in which the presence of one species has a negative effect

on another, but the first species is unaffected. For example, a herd of elephants walking across a

landscape may crush fragile plants. Amensalistic interactions commonly result when one species

produces a chemical compound that is harmful to another species. The chemical ‘juglone’

produced in the roots of black walnut inhibit the growth of other trees and shrubs, but has no

effect on the walnut tree.

Penicillium is a group of common mould species, many of which produce antibiotics (such as

penicillin). These antibiotics kill certain types of bacteria. The antibiotics produced by the

moulds are simply a waste product, produced during their metabolism (as they break down their

food). While the waste product kills bacteria, the penicillium are unaffected.

You might also like

- ScienceDocument2 pagesSciencegemNo ratings yet

- 5 Types of Ecological Relationships ExplainedDocument1 page5 Types of Ecological Relationships Explainedjoan marie PeliasNo ratings yet

- Ecological Relationships Describe The Interactions Between and Among Organisms Within Their EnvironmentDocument39 pagesEcological Relationships Describe The Interactions Between and Among Organisms Within Their Environmentjallie niepesNo ratings yet

- Five Types of Ecological RelationshipsDocument5 pagesFive Types of Ecological RelationshipsMikael TelenNo ratings yet

- Organisms Occupy What Are Called NichesDocument5 pagesOrganisms Occupy What Are Called NichesGabriel Mellar NaparatoNo ratings yet

- Ecological RelationshipsDocument2 pagesEcological RelationshipsJoya Sugue AlforqueNo ratings yet

- Animal InteractionDocument6 pagesAnimal InteractionZiya ShaikhNo ratings yet

- BIO 111 NOTES (Autosaved) - 082311Document10 pagesBIO 111 NOTES (Autosaved) - 082311Borisade Tolulope VictorNo ratings yet

- Commensalism: Symbiosis SpeciesDocument5 pagesCommensalism: Symbiosis SpeciesAko C RcNo ratings yet

- Relationships Between AnimalsDocument2 pagesRelationships Between AnimalsAna laura FloresNo ratings yet

- Ecological RelationshipDocument3 pagesEcological RelationshipNikel CanNo ratings yet

- ANIMALS SHOW COMMENSALISM IN RAINFORESTDocument3 pagesANIMALS SHOW COMMENSALISM IN RAINFORESTNikel CanNo ratings yet

- Interaction of ParaSitism, Commensalism, and CompetitionDocument14 pagesInteraction of ParaSitism, Commensalism, and CompetitionMichelle LebosadaNo ratings yet

- Worksheet For Inter-Specific RelationshipsDocument4 pagesWorksheet For Inter-Specific RelationshipsJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Pee M4 ReviewerDocument4 pagesPee M4 ReviewerAster GabbNo ratings yet

- Species InteractionDocument1 pageSpecies Interactionpang batzNo ratings yet

- Mutualism and its Role in EcologyTITLEDocument6 pagesMutualism and its Role in EcologyTITLEHarshit SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Ecological InteractionsDocument3 pagesEcological InteractionsCheryl Jeanne PalajeNo ratings yet

- Species Interaction TypesDocument3 pagesSpecies Interaction TypesObrien CelestinoNo ratings yet

- Symbiotic Relationships Are A Special Type of Interaction Between SpeciesDocument2 pagesSymbiotic Relationships Are A Special Type of Interaction Between SpeciesRjvm Net Ca FeNo ratings yet

- Different Types of Ecological Interactions and Their ExamplesDocument1 pageDifferent Types of Ecological Interactions and Their ExampleshannamNo ratings yet

- Species InteractionDocument4 pagesSpecies Interactionckhimmy_93No ratings yet

- Trophic Levels and Species Interactions in EcosystemsDocument4 pagesTrophic Levels and Species Interactions in EcosystemsBaileyNo ratings yet

- Species InteractionsDocument4 pagesSpecies InteractionsAbellya Nella MorteNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document38 pagesChapter 5Brent SorianoNo ratings yet

- Biological InteractionDocument4 pagesBiological InteractionMaynard PascualNo ratings yet

- Form 3 Biology - Symbiotic RelationshipsDocument4 pagesForm 3 Biology - Symbiotic RelationshipsJoann LambertNo ratings yet

- Relationships Within The Ecosystem: MutualismDocument6 pagesRelationships Within The Ecosystem: MutualismLietOts KinseNo ratings yet

- Population Interaction Ip Project BioDocument20 pagesPopulation Interaction Ip Project BioAmrita SNo ratings yet

- Inter Specific InteractionDocument7 pagesInter Specific InteractionSandeep kumar SathuaNo ratings yet

- Population InteractionDocument3 pagesPopulation Interactionrikitasingh2706No ratings yet

- General Veterinary Parasitology and Helminthology BernardDocument88 pagesGeneral Veterinary Parasitology and Helminthology Bernardprabha alphonsa50% (4)

- Note May 19 2014Document4 pagesNote May 19 2014api-248235433No ratings yet

- Interrelationship Among Plants and Animals: PresenterDocument20 pagesInterrelationship Among Plants and Animals: PresenterMicaela Kaye Margullo MontereyNo ratings yet

- Tugas Resume EkoUm TM 7Document4 pagesTugas Resume EkoUm TM 7afkarin kamilaNo ratings yet

- Organisms InteractionDocument3 pagesOrganisms InteractionMary Ylane LeeNo ratings yet

- Types of RelationshipsDocument9 pagesTypes of RelationshipsStephen GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Plant Symbionts InteractionDocument13 pagesPlant Symbionts InteractionIram TahirNo ratings yet

- Symbiotic Relationship and Its TypesDocument33 pagesSymbiotic Relationship and Its TypesMayuri Vohra0% (1)

- Insects and The Biotic EnvironmentDocument4 pagesInsects and The Biotic Environmentirfan khanNo ratings yet

- AGR 202_Introductory Entomology_lecture note III (1)Document8 pagesAGR 202_Introductory Entomology_lecture note III (1)abdulraazik1811No ratings yet

- Abiotic and Biotic Factors in EcosystemDocument3 pagesAbiotic and Biotic Factors in EcosystemLeilanie SantosNo ratings yet

- Discussion Proper in LPDocument4 pagesDiscussion Proper in LPJazzel Queny ZalduaNo ratings yet

- Ecological InteractionsDocument4 pagesEcological Interactionsweng sumampongNo ratings yet

- Principles of Ecology, Interaction of Organisms Within The EnvironmentDocument3 pagesPrinciples of Ecology, Interaction of Organisms Within The EnvironmentdinakahNo ratings yet

- TERM Paper: Topic-Symbiotic RelationshipsDocument8 pagesTERM Paper: Topic-Symbiotic RelationshipsVikas DaiyaNo ratings yet

- Esb Kamonyi Biology Notes s3 2021-2022Document127 pagesEsb Kamonyi Biology Notes s3 2021-2022GadNo ratings yet

- Escuela Anglo Americana: Charles DarwinDocument8 pagesEscuela Anglo Americana: Charles DarwinAndres AguileraNo ratings yet

- Fig. 5 Intraspecific Competition SourceDocument31 pagesFig. 5 Intraspecific Competition SourceMonrey SalvaNo ratings yet

- SymbiosisDocument43 pagesSymbiosisShubhanshu SrivastavNo ratings yet

- Community EcologyDocument23 pagesCommunity EcologyCjoy MañiboNo ratings yet

- Biology Unit 4Document30 pagesBiology Unit 4Kayleen PerdanaNo ratings yet

- EcologyDocument3 pagesEcologySusmita Biswas SathiNo ratings yet

- Interspecific RelationshipsDocument4 pagesInterspecific RelationshipsJohn OsborneNo ratings yet

- Unidad IV. - Trabajo Medicina Veterinaria Ingles InstrumentalDocument3 pagesUnidad IV. - Trabajo Medicina Veterinaria Ingles InstrumentalRicardo RodríguezNo ratings yet

- 5.3.1. Lesson#1 - (Species Interaction) - General Ecology Lecture BI 2-ADocument3 pages5.3.1. Lesson#1 - (Species Interaction) - General Ecology Lecture BI 2-AShareeze GomezNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Mushrooms: An Illustrated Guide to the Extraordinary Power of MushroomsFrom EverandThe Little Book of Mushrooms: An Illustrated Guide to the Extraordinary Power of MushroomsNo ratings yet

- Fungi Are Not Plants - Biology Book Grade 4 | Children's Biology BooksFrom EverandFungi Are Not Plants - Biology Book Grade 4 | Children's Biology BooksNo ratings yet

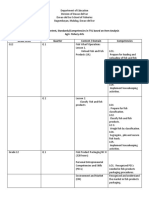

- Number of Students RXI For ImmersionDocument11 pagesNumber of Students RXI For ImmersionKing ZorNo ratings yet

- % of Attendance % of Enrolment I-Daisy I-Rose II-Lily II-Rosal III-Orchid III-Camia IV-CosmosDocument1 page% of Attendance % of Enrolment I-Daisy I-Rose II-Lily II-Rosal III-Orchid III-Camia IV-CosmosKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Form 3 July 2016Document1 pageForm 3 July 2016King ZorNo ratings yet

- Davao del Sur Elementary School Absence Records July 2016Document1 pageDavao del Sur Elementary School Absence Records July 2016King ZorNo ratings yet

- SIPDocument55 pagesSIPKing ZorNo ratings yet

- K to 12 Music Curriculum Guide Provides OverviewDocument94 pagesK to 12 Music Curriculum Guide Provides OverviewJasellay CamomotNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 BeveragesDocument27 pagesChapter 4 Beveragesjaydaman08No ratings yet

- Legal Writing ExerciseDocument1 pageLegal Writing ExerciseKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Balutakay Elementary School Improvement Plan 2015-2016Document55 pagesBalutakay Elementary School Improvement Plan 2015-2016King ZorNo ratings yet

- Felipe-Innocencia Deluao National High School: Maintaining Computer Systems and NetworkDocument2 pagesFelipe-Innocencia Deluao National High School: Maintaining Computer Systems and NetworkKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Appendix B: Tanggapang Panrehiyon XiDocument3 pagesAppendix B: Tanggapang Panrehiyon XiKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Grade-9 Tle ReportDocument5 pagesGrade-9 Tle ReportKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Document IPADocument1 pageDocument IPAKing ZorNo ratings yet

- K to 12 Music Curriculum Guide Provides OverviewDocument94 pagesK to 12 Music Curriculum Guide Provides OverviewJasellay CamomotNo ratings yet

- SIP 2018 TemplateDocument62 pagesSIP 2018 TemplateKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Authority To TravelDocument1 pageAuthority To TravelKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Davao del Sur School of Fisheries Least Mastered ContentDocument3 pagesDavao del Sur School of Fisheries Least Mastered ContentKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 BeveragesDocument27 pagesChapter 4 Beveragesjaydaman08No ratings yet

- Conference ItineraryDocument1 pageConference ItineraryKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Authority To Travel: Purok NG Bansalan EastDocument3 pagesAuthority To Travel: Purok NG Bansalan EastKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Authorization ChedDocument1 pageAuthorization ChedKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Rationale: Quantitative Research ContentDocument7 pagesRationale: Quantitative Research ContentKing ZorNo ratings yet

- TLE and TVL content standards teachers find difficultDocument2 pagesTLE and TVL content standards teachers find difficultKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing ExerciseDocument1 pageLegal Writing ExerciseKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesRepublic of The PhilippinesKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Curr IntroDocument52 pagesCurr IntroNawafNo ratings yet

- Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesRepublic of The PhilippinesKing ZorNo ratings yet

- 2011 WE Application FormDocument6 pages2011 WE Application FormcrisjavaNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report No Smoking 2019Document3 pagesNarrative Report No Smoking 2019King ZorNo ratings yet

- The Man Who Shouted Teresa Italo CalvinoDocument1 pageThe Man Who Shouted Teresa Italo CalvinoKing ZorNo ratings yet

- Cucumber Research ArticleDocument22 pagesCucumber Research ArticleDaisy SarsueloNo ratings yet

- Reproduction of FungiDocument12 pagesReproduction of FungiIDSP Uttarakhand100% (1)

- IntroductionDocument3 pagesIntroductionRodel MarataNo ratings yet

- Classification of MicroorganismsDocument38 pagesClassification of MicroorganismsPrasad SwaminathanNo ratings yet

- GREEN PharmacognosyDocument14 pagesGREEN PharmacognosyZian NakiriNo ratings yet

- NEET CUMULATIVE TEST -2 Biology QuestionsDocument24 pagesNEET CUMULATIVE TEST -2 Biology Questionsbal_thakreNo ratings yet

- CertificateofAnalysis E. Aerogenes ATCC 13048Document2 pagesCertificateofAnalysis E. Aerogenes ATCC 13048magnetovsjavierNo ratings yet

- Affect of Phytohormons in Leaf SenescenceDocument29 pagesAffect of Phytohormons in Leaf Senescencemasoomi_farhad2030No ratings yet

- Table of Specifications: Luis Ferrer Iii Memorial School Second Periodical Test in English IvDocument17 pagesTable of Specifications: Luis Ferrer Iii Memorial School Second Periodical Test in English IvShiela E. EladNo ratings yet

- 66 KumarDocument10 pages66 KumarVakamalla SubbareddyNo ratings yet

- Efficient Micropropagation Protocol For Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium PDFDocument11 pagesEfficient Micropropagation Protocol For Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium PDFKassius Augusto da RosaNo ratings yet

- FFTC Document Database: Site Search SearchDocument2 pagesFFTC Document Database: Site Search SearchaiktiplarNo ratings yet

- Translocation in the PhloemDocument37 pagesTranslocation in the PhloemDanae ForresterNo ratings yet

- Mark Schem Es: Quick Quiz Matching End of Unit Test Marks To NC LevelsDocument1 pageMark Schem Es: Quick Quiz Matching End of Unit Test Marks To NC LevelsSumathi Ganasen100% (1)

- Symbiotic Relationships in EcosystemsDocument14 pagesSymbiotic Relationships in EcosystemsJane PaguiaNo ratings yet

- Medicinal Plants: A Review: Journal of Plant SciencesDocument6 pagesMedicinal Plants: A Review: Journal of Plant Scienceskeshav shishyaNo ratings yet

- 57-1-2 BiologyDocument8 pages57-1-2 BiologySiddharth ShankarNo ratings yet

- Control and Coordination in AnimalsDocument5 pagesControl and Coordination in AnimalsNimendraNo ratings yet

- Rose bush → Greenfly → Ladybird → Sparrow → HawkDocument41 pagesRose bush → Greenfly → Ladybird → Sparrow → HawkTysonTanNo ratings yet

- Un FruitfulnessDocument20 pagesUn FruitfulnessVikas JainNo ratings yet

- The Gardeners Dictionary - Vol 1Document534 pagesThe Gardeners Dictionary - Vol 1razno001No ratings yet

- TittlesDocument8 pagesTittlesChrisma EderNo ratings yet

- Everything You Need to Know About Candida Albicans and How to Fight ItDocument24 pagesEverything You Need to Know About Candida Albicans and How to Fight ItMatt OakleyNo ratings yet

- The many uses and benefits of papayasDocument6 pagesThe many uses and benefits of papayasfkkfoxNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Ipapasa NG Sept 10Document13 pagesResearch Paper Ipapasa NG Sept 10AJ Sakandal0% (1)

- Lesson Plan For Science 3 (Second Quarter)Document6 pagesLesson Plan For Science 3 (Second Quarter)Dinah DimagibaNo ratings yet

- Asexual and Sexual Reproduction QuizDocument2 pagesAsexual and Sexual Reproduction QuizShannen Abegail FernandezNo ratings yet

- AESA IPM Package ChilliesDocument93 pagesAESA IPM Package Chilliesgowri2703No ratings yet

- Classification of Crude DrugsDocument4 pagesClassification of Crude DrugsPawan KumarNo ratings yet

- Avocado PDFDocument16 pagesAvocado PDFknot8No ratings yet