Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Zoonotic Parasitic Infections

Uploaded by

Nanda Finisa0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views1 pageParasit

Original Title

Parasites

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentParasit

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views1 pageZoonotic Parasitic Infections

Uploaded by

Nanda FinisaParasit

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

Zoonotic Parasitic Infections

Berkowitz, 2Travis Seymour, VMD, MLAS 1Rachel

1Stanford University (Class of 2016), 2Department of Comparative Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine

Baylisascaris procyonis Echinococcus granulosus Ancylostoma caninum

The canine hookworm is a nematode that can cause cutaneous larval migrans

in humans.5

• In dogs, worms penetrate the skin, migrate through tissues (via lymphatics and

venous system) to the lungs, are coughed up and swallowed, and grow and

mature in the small intestine7

• Larvae may migrate to other tissues such as mammary glands, so puppies can

be infected through nursing6

• Infection is by egg ingestion or larval penetration of the skin

• In humans, larvae are unable to complete their normal life cycle, therefore they

migrate throughout the epidermis causing tissue damage and irritation7

• Infection can be successfully treated with albendazole or ivermectin in humans6

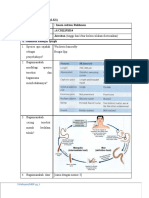

Figure 2. Baylisascaris procyonis life cycle2.

Figure 3. Echinococcus granulosus life cycle (http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/html/Echinococcosis.htm).

The raccoon ascarid is a major zoonotic risk that can infect humans and

domestic species resulting in significant disease. The canine tapeworm is a cestode that can cause hydatid cyst disease in

humans.4

• In raccoons, larvae hatch and penetrate the intestinal mucosa, where they grow and • In dogs, larvae hatch and penetrate the intestinal mucosa, where they grow and

mature mature

• Infections in the definitive host are generally asymptomatic, though high worm • Infected dogs are usually asymptomatic, and younger dogs are more susceptible

burdens may occasionally cause intestinal obstruction and death to infection

• Eggs are shed in the feces 50-76 days after infection; ingested from contaminated • Humans are infected by ingestion of eggs/proglottids from the environment

soil Figure 5. Ancylostoma caninum life cycle.

• Infection in humans results in damaging cyst development in the lungs or liver

• In intermediate/aberrant hosts, larvae hatch and migrate randomly throughout the as the larvae mature and enlarge 3 • Transmission in humans is via skin contact with infected soil or other fomites7

body as they grow, causing considerable tissue damage that results in visceral and • Infection is most common in the developing world5

neural larval migrans A B C D • Larvae are able to penetrate skin and migrate through other tissues

• Liver, lungs, CNS commonly affected • Adult worms in the intestines cause severe eosinophilic enteritis and infiltration

• When larvae enter the brain, prolonged migration causes extensive neural damage of the bowel wall6

A B C D

A B C

E F Figure 4.

A. Scolex on cross section, (wikipedia.org)

B. Adult worm9 C. Hydatid cyst containing

multiple larvae10 D. Hydatid cysts excised

from human peritoneal cavity 7

E. Cerebral hydatid cysts on MRI

Figure 1. A. Larvated and non-larvated infective ascarid eggs 1 B. Cross section of an (radiopaedia.org) F. Infected liver with

adult nematode (buzzle.com). C. Larva of B. procyonis hatching from an egg 8 D. B. hydatid cysts11

procyonis larvae in cross section, rabbit cerebrum (aapredbook.aappublications.org) D E Figure 6.

A. A. caninum egg12 B. Adult worm

• Visceral or ocular larval migrans has been reported in children and adults • Prevalent worldwide, especially in developing regions (meyeucon.org) C. Human skin damage

caused by migrating worms (wikipedia.org)

• Most prevalent in urban/suburban areas of North America where raccoons live in • Cystic infection is persistent in rural areas where livestock act as intermediate D. Adult worms in vivo (bullwrinkle.com)

E. Anterior end of adult worm 12

close proximity to humans hosts3

• Consumption of infected soil the most likely route of infection1 • People living in close proximity to dogs fed on raw livestock offal are at high

• Treatment is rarely successful; prevent by avoiding contact with raccoon feces risk of infection

• Baiting raccoons with anthelmintic-medicated feed can reduce prevalence in the • Prevention is achieved by restraining dogs and limiting their access to raw meat

wild2 or wildlife3

References:

1. Roussere GP, Murray WJ, Raudenbush CB, Kutilek MJ, Levee DJ, Kazacos KR Raccoon roundworm eggs near homes and risk for larva migrans disease, California communities. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1516–23. 4. Feldmeier H, and Schuster A. "Mini Review: Hookworm-related Cutaneous Larva Migrans." European Journal Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease 31 (2012): 915-18.

2. Bauer C. "Baylisascariosis—Infections of Animals and Humans with ‘unusual’ Roundworms." Veterinary Parasitology 193.4 (2013): 404-12. 5. Sarkar D, Ray S, and Saha M. “Peritoneal hydatidosis: A rare form of a common disease.” Tropical Parasitology 1.2 (2011): 123-125.

3. Otero-Abad B, and Torgerson PR. "A Systematic Review of the Epidemiology of Echinococcosis in Domestic and Wild Animals." Ed. Hector H. Garcia. 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Parasites – Baylisascaris. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/baylisascaris/

PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 7.6 (2013): E2249. 7. Upton SJ. Animal Parasitology – Biology 625. Retrieved from http://www.k-state.edu/parasitology/625tutorials/Tapeworm03.html

3. Carmena D, and Cardona GA. "Canine Echinococcosis: Global Epidemiology and Genotypic Diversity." Elsevier 128 (2013): 441-60. Web. 13 Mar. 2014. 8. Min DY, Ahn MH, Ryu RS. Web Atlas of Medical Parasitology. The Korean Society of Parasitology. Retrieved from http://www.atlas.or.kr/atlas/alphabet_view.php?my_codeName=Echinococcus%20granulosus

4. Veraldi, S, Persico MC, Francia C, and Schianchi R. "Chronic Hookworm-related Cutaneous Larva Migrans." International Journal of Infectious Diseases 17.4 (2013): E277-279. 9. Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Echinococcosis (2014). Retrieved from http://www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,1607,7-153-10370_12150_12220-117400--,00.html

5. Bowman DD, Montgomery SP, Zajac AM, Eberhard ML, and Kazacos KR. "Hookworms of Dogs and Cats as Agents of Cutaneous Larva Migrans." Trends in Parasitology 26.4 (2010): 162-67. 10. Nolan TJ. Ancylostoma caninum. University of Pennsylvania, School of Veterinary Medicine (2004). Retrieved from http://cal.vet.upenn.edu/projects/dxendopar/parasitepages/hooklungstrongyloides/a_canis.html

You might also like

- Phylum NematodaDocument11 pagesPhylum NematodaKristine Aranna ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Malassezia Pachydermatis Can Be - Bottle-Shaped, NonDocument6 pagesMalassezia Pachydermatis Can Be - Bottle-Shaped, NonMA Orejas RamosNo ratings yet

- CANIVERM ORAL PASTE FOR DOGS AND CATSDocument20 pagesCANIVERM ORAL PASTE FOR DOGS AND CATSMihaela RUSUNo ratings yet

- Nematodes: Specie Infecti VE Stage Diagnos TIC Stage Morphology Pathogen Esis Diagnosi S Treatme NT Life CycleDocument4 pagesNematodes: Specie Infecti VE Stage Diagnos TIC Stage Morphology Pathogen Esis Diagnosi S Treatme NT Life CycleMarinelle TumanguilNo ratings yet

- Lesson 10Document6 pagesLesson 10daryl jan komowangNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Lesson 5 Helminths (1)Document11 pagesModule 2 Lesson 5 Helminths (1)YUSON DIANAMARIENo ratings yet

- Blood and Tissue Protozoa (Con't) : DR - Mehru Nisha Mehrunisha@unikl - Edu.myDocument35 pagesBlood and Tissue Protozoa (Con't) : DR - Mehru Nisha Mehrunisha@unikl - Edu.myNida RidzuanNo ratings yet

- Nematodes (Round Worms) Comparison TableDocument4 pagesNematodes (Round Worms) Comparison TableJoshua TrinidadNo ratings yet

- طفيليات عملي ٢Document19 pagesطفيليات عملي ٢xexs887No ratings yet

- 7 - Nematodes (Aphasmids and Phasmids)Document9 pages7 - Nematodes (Aphasmids and Phasmids)Scarlet WitchNo ratings yet

- STH's Unholy TrinityDocument9 pagesSTH's Unholy TrinityEunice AndradeNo ratings yet

- Echinostoma IlocanumDocument3 pagesEchinostoma IlocanumChristie Raye NapuliNo ratings yet

- Medical Parasitology A Self Instructional Text PDFDriveDocument60 pagesMedical Parasitology A Self Instructional Text PDFDriveDenise Sta. AnaNo ratings yet

- ParasiteDocument16 pagesParasiteFlorence Lynn BaisacNo ratings yet

- Emily Scroggs Microorganisms Affecting The KidneyDocument1 pageEmily Scroggs Microorganisms Affecting The KidneyMicroposterNo ratings yet

- 11 Parasitology - Phasmids 4Document4 pages11 Parasitology - Phasmids 4maqmmNo ratings yet

- Trematodes: 2. MiracidiaDocument3 pagesTrematodes: 2. MiracidiaBikram ChohanNo ratings yet

- Parasitology: Representatives of Phylum NematodaDocument2 pagesParasitology: Representatives of Phylum Nematodasen tobleroneNo ratings yet

- Ascaris Lumbricoides: Common Roundworm InfectionDocument8 pagesAscaris Lumbricoides: Common Roundworm InfectionEunice AndradeNo ratings yet

- NEMATODADocument3 pagesNEMATODAChristian Dave PascualNo ratings yet

- 2.13 - NemathelminthesDocument4 pages2.13 - NemathelminthesLunaNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Measles Pathogenesis of Measles: By: Rey Martino (For Educational Use Only)Document6 pagesPathogenesis of Measles Pathogenesis of Measles: By: Rey Martino (For Educational Use Only)rey martino100% (2)

- SLP Parasitic Diseases of Central Nervous System-ANSWER SGDocument13 pagesSLP Parasitic Diseases of Central Nervous System-ANSWER SGDanial MazukiNo ratings yet

- LKS Helminth kelenjar lymph dan pembuluh venaDocument25 pagesLKS Helminth kelenjar lymph dan pembuluh venaMECNESIA Tutor 2No ratings yet

- Enterobius Vermicularis) : Hawri H. Mohammed H.D., M.Sc. ParasitologyDocument9 pagesEnterobius Vermicularis) : Hawri H. Mohammed H.D., M.Sc. ParasitologyHawre NajmaddinNo ratings yet

- Adult Tapeworm Is LargerDocument18 pagesAdult Tapeworm Is LargerAbby SiervoNo ratings yet

- Io Hyatid CystDocument3 pagesIo Hyatid CystSam Bradley DavidsonNo ratings yet

- Parasite Profile ChartDocument40 pagesParasite Profile Chartapi-324380555100% (3)

- Chapter 10 Non-Specific Host Defense MechanismDocument5 pagesChapter 10 Non-Specific Host Defense MechanismEanna ParadoNo ratings yet

- FUNGIDocument9 pagesFUNGIzoeyNo ratings yet

- Longer The: CurvedDocument1 pageLonger The: CurvedSayandeep DuttaNo ratings yet

- Parasitology: Helminthology: HelminthsDocument21 pagesParasitology: Helminthology: Helminthstony montanNo ratings yet

- HelminthesDocument3 pagesHelminthesMichael Vincent P.No ratings yet

- Note Chapter 10Document10 pagesNote Chapter 10Amirr4uddinNo ratings yet

- Different Groups of HelminthsDocument6 pagesDifferent Groups of HelminthsST - Roselyn BellezaNo ratings yet

- Helminths and Protozoa: Parasitic Worms and Single-Celled ParasitesDocument6 pagesHelminths and Protozoa: Parasitic Worms and Single-Celled ParasitesSuzanne RibsskogNo ratings yet

- Intestinal FlukesDocument24 pagesIntestinal Flukesroy mata88% (8)

- ParasitesDocument56 pagesParasitesdenis marselaNo ratings yet

- Suggested ResponsesDocument3 pagesSuggested ResponsesVrutika PatelNo ratings yet

- Based On Belizario:: Fasciolopsis BuskiDocument6 pagesBased On Belizario:: Fasciolopsis BuskimaqmmNo ratings yet

- Lect 2Document11 pagesLect 2Sara AliNo ratings yet

- StreptococcusDocument3 pagesStreptococcusAlvin Anique MandacNo ratings yet

- Leyte Normal University Science Unit: Lab Activity # 7 NematodaDocument11 pagesLeyte Normal University Science Unit: Lab Activity # 7 NematodaEdward Glenn AbaigarNo ratings yet

- FungiDocument3 pagesFungikrystal TortolaNo ratings yet

- April 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: TrematodesDocument9 pagesApril 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: Trematodesthe someoneNo ratings yet

- Activity-4-TREMATODES GROUP 4 FINAL.Document10 pagesActivity-4-TREMATODES GROUP 4 FINAL.the someoneNo ratings yet

- Parasite Packet 1Document12 pagesParasite Packet 1api-595420397No ratings yet

- Nematodes (Round Worms) Lec 7 Fall 2021 PDFDocument12 pagesNematodes (Round Worms) Lec 7 Fall 2021 PDFMk KassemNo ratings yet

- Exercise 9Document9 pagesExercise 9Bishal KunworNo ratings yet

- Exercise 9 PARA LABDocument9 pagesExercise 9 PARA LABBishal KunworNo ratings yet

- Name: - Akmad A. Sugod - Date: January 5, 2023 - Course & Year: - BSED-Biology, 4 Year - Prof: Anita V. SarmagoDocument10 pagesName: - Akmad A. Sugod - Date: January 5, 2023 - Course & Year: - BSED-Biology, 4 Year - Prof: Anita V. SarmagoAkmad SugodNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity: BacteriaDocument12 pagesBiodiversity: BacteriajpkaomeNo ratings yet

- Understanding the life cycle and transmission of the beef tapeworm (Taenia saginataDocument3 pagesUnderstanding the life cycle and transmission of the beef tapeworm (Taenia saginataحسام الدين إسماعيلNo ratings yet

- Parasitology Metazoa: ProtozoaDocument7 pagesParasitology Metazoa: ProtozoaTrishaNo ratings yet

- Case 9 HelminthiasisDocument16 pagesCase 9 HelminthiasisNicole NgoNo ratings yet

- Parasitology-Lec 5 TrematodesDocument5 pagesParasitology-Lec 5 Trematodesapi-3743217100% (2)

- Ciclos 5to Seminario Protozoarios de Sangre y Tejidos II. API Complex ADocument2 pagesCiclos 5to Seminario Protozoarios de Sangre y Tejidos II. API Complex Aapi-3697245No ratings yet

- Topic Summary-NematodesDocument2 pagesTopic Summary-Nematodessakalam shipper48No ratings yet

- Ascariasis Ada GambarDocument4 pagesAscariasis Ada GambarninaNo ratings yet

- BSAH SAH CO2 Chamber M1-TSFM-2Document2 pagesBSAH SAH CO2 Chamber M1-TSFM-2Nanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- FH1 Isolator 1Document1 pageFH1 Isolator 1Nanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- FH1 Isolator 1Document1 pageFH1 Isolator 1Nanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For NIH Rodent Transportation: A. GeneralDocument4 pagesGuidelines For NIH Rodent Transportation: A. GeneralNanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- FH1 Isolator 1Document1 pageFH1 Isolator 1Nanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- Nanda Finisa PoemDocument1 pageNanda Finisa PoemNanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Trchinella SpirallisDocument1 pageDaftar Pustaka Trchinella SpirallisNanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- The Process of Pinioning Involves The Cutting of One Wing at The Carpel JointDocument23 pagesThe Process of Pinioning Involves The Cutting of One Wing at The Carpel JointNanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- Food ChainsDocument3 pagesFood ChainsNanda Finisa BlueVoiceNo ratings yet

- Happy Feet 2 (SDH Digabung)Document7 pagesHappy Feet 2 (SDH Digabung)Nanda FinisaNo ratings yet

- University of Madras Syllabus for Softskills CoursesDocument33 pagesUniversity of Madras Syllabus for Softskills Coursesseema sweetNo ratings yet

- Carpenter - Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2nd Ed PDFDocument240 pagesCarpenter - Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 2nd Ed PDFAngie MirandaNo ratings yet

- Unit I - Diversity in Living WorldDocument21 pagesUnit I - Diversity in Living WorldChris MohankumarNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan About Symbiotic RelationshipDocument8 pagesLesson Plan About Symbiotic RelationshipRica Ancheta100% (1)

- 2012 - Prediction of The Hematocrit of Dried Blood Spots Via Potassium Measurement On A Routine Clinical Chemistry AnalyzerDocument14 pages2012 - Prediction of The Hematocrit of Dried Blood Spots Via Potassium Measurement On A Routine Clinical Chemistry AnalyzerFede0No ratings yet

- Atmospheric Homeostasis: The Gaia HypothesisDocument9 pagesAtmospheric Homeostasis: The Gaia HypothesisLuis Alonso Hormazabal DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Common Weeds in Oil Palm PlantationDocument8 pagesCommon Weeds in Oil Palm Plantationalanzo8988% (17)

- El Engaño Del EvolucionismoDocument136 pagesEl Engaño Del EvolucionismoRichard OliverosNo ratings yet

- Biology Exam 2022 Form4Document12 pagesBiology Exam 2022 Form4Yahya Abdiwahab100% (1)

- Folds of Peritoneum: Abdomen and PelvisDocument100 pagesFolds of Peritoneum: Abdomen and PelvissrisakthiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7chromosome Banding and IdentificationDocument18 pagesChapter 7chromosome Banding and IdentificationJed Naziel AvilaNo ratings yet

- Analyze Paragraphs on Professors' Duties, Open-Heart Surgery, Anti-Smoking Efforts, Laser SurgeryDocument2 pagesAnalyze Paragraphs on Professors' Duties, Open-Heart Surgery, Anti-Smoking Efforts, Laser Surgeryratu wilhelminaNo ratings yet

- Brihaspati or JupiterDocument17 pagesBrihaspati or JupiterAshish RajeNo ratings yet

- General Veterinary Macroscopic Anatomy: Osteology: Storage Cell Formation) of FatsDocument34 pagesGeneral Veterinary Macroscopic Anatomy: Osteology: Storage Cell Formation) of FatsneannaNo ratings yet

- Lab Report 5Document9 pagesLab Report 5Krizia Corrine St. PeterNo ratings yet

- Acid RainDocument5 pagesAcid RainJasmine JaizNo ratings yet

- Obat Herbal Untuk AritmiaDocument17 pagesObat Herbal Untuk AritmiaFerina Nadya PratamaNo ratings yet

- 6177-Article Text-39080-1-10-20160922Document14 pages6177-Article Text-39080-1-10-20160922Fadlika AhmadiNo ratings yet

- Welfare EssaysDocument6 pagesWelfare Essaysfz67946y100% (2)

- Ness Family History Part 1Document78 pagesNess Family History Part 1dbryant0101100% (1)

- Autologous Platelet Concentrate Preparations in Dentistry: Research Article Open AccessDocument10 pagesAutologous Platelet Concentrate Preparations in Dentistry: Research Article Open AccessIvan GalicNo ratings yet

- DLSU A Plastic Ocean Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesDLSU A Plastic Ocean Reaction PaperJued Cisneros100% (1)

- Medical Biology: T I L Ea A K - 1 G A M A TaDocument376 pagesMedical Biology: T I L Ea A K - 1 G A M A Tatiffylola100% (1)

- Functions of The Muscular SystemDocument5 pagesFunctions of The Muscular SystemJorge Agustín AndradeNo ratings yet

- Rotator Cuff ArthropathyDocument10 pagesRotator Cuff ArthropathyNavdeep GogiaNo ratings yet

- Huang, Chi, Chien - 2018 - Size-Exclusion Chromatography Using Reverse-Phase Columns For Protein SeparationDocument12 pagesHuang, Chi, Chien - 2018 - Size-Exclusion Chromatography Using Reverse-Phase Columns For Protein Separationκ.μ.α «— Brakat»No ratings yet

- Report :SELF HEALING CONCRETEDocument19 pagesReport :SELF HEALING CONCRETEPrabhat Kumar Sahu94% (18)

- Plant Growth and Development. Botany. FinalDocument47 pagesPlant Growth and Development. Botany. FinalMelanie Lequin CalamayanNo ratings yet

- STEM - GC11CR If G 36Document14 pagesSTEM - GC11CR If G 36Rachel Joy Dela RosaNo ratings yet