Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Srbi Nakon Kosova PDF

Srbi Nakon Kosova PDF

Uploaded by

damirprasnikar0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views21 pagesOriginal Title

SRBI NAKON KOSOVA.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views21 pagesSrbi Nakon Kosova PDF

Srbi Nakon Kosova PDF

Uploaded by

damirprasnikarCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 21

II

BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES:

SERBIAN SURVIVAL IN THE

YEARS AFTER KOSOVO

Nicholas C. J. Pappas

One of the least understood yet most important periods of Ser-

bian history is the era of foreign subjugation from the battle of

Kosovo in 1389 to the First Serbian Uprising in 1804. While this

period began earlier and ended later for many Serbs, these dates

are often mentioned as the twilight of medieval Serbia and the

dawn of modern Serbia. Most Serbs have looked upon these 415

years as a dark age in which the glories of Serbia’s medieval leg-

acy were extinguished only to be rekindled with the rise of mod-

ern Serbia and the unification of the South Slavs in the nine-

teenth and twentieth centuries. This period reveals a story of the

endurance, fortitude, and courage of a people subdued by and

subject to two mighty empires, the Ottoman and the Habsburg,

who survived and reemerged as a proud independent nation in

modern times. The story of this survival is a very complex one,

involving many political, social, economic, and cultural trends

and events, not only involving the Serbs’ relations with the Otto-

man and Habsburg Empires, but also with Venice and other Eu-

ropean states and societies. In recent years many books, articles

and essays have been written on various aspects of the history of

the Serbs in the period after Kosovo and have given us new in-

sights into how and why the Serbs survived as a people and re-

emerged as a nation after centuries of foreign rule.

17

18 Serbia's Historical Heritage

This brief study will limit itself to looking at five basic factors

in the survival of the Serbs in the period of Turkish and Austrian

Rule. These factors are: vassalage and autonomy, military service

and armed resistance, migration and emigration, the Serbian Or-

thodox Church, and Serbian epic culture.

The first factor to be investigated is that of vassalage and au-

tonomy. In order to understand the importance that vassalage

and autonomy had as a factor in Serbian survival, it must be re-

membered that the Ottoman Empire, while being the most pow-

erful and absolute monarchy in the world in the sixteenth cen-

tury, was not an all-encompassing centralized state of later times.

Most of the subjects of the Sultan were ruled indirectly through

feudatories who were granted land and peasants to till it in re-

turn for military service. These feudatories, known as sipahiler,

provided the main cavalry forces for the Sultan. Different areas

had different degrees of imperial control and autonomy. In addi-

tion, the Ottoman millet (nation) system, which divided the em-

pire’s subjects according to religious affiliation, gave some au-

thority in civil government and law to religious leaders. The

Muslim, Jewish, Orthodox (Greek and Serbian), Armenian and

other ethno-religious groups had their own courts within their

respective millets. After the initial shock and destruction of con-

quest, the Ottoman state’s main interest was in maintaining its

revenues and armed forces. At its height the Ottoman adminis-

tration was not as oppressive as other states in Europe. It only

became onerous and stifling when its central authority began to

break down from the late sixteenth century on and the popula-

tion began to suffer from rapacious local governors, greedy land-

owners, freebooting soldiers, and corrupt tax collectors.!

Similarly the Austrian or Habsburg Empire was not uniformly

oppressive in the sixteenth through the eighteenth century. The

Holy Roman Empire was a patchwork of different Habsburg

patrimonies with different political, legal, and social conditions,

as well as different relations with Vienna. The Serbs, who came

under Habsburg rule as a result of emigration and military ser-

vice, as well as Habsburg expansion, were often granted privi-

leges from the crown which they had to defend from the en-

croachments of local nobility, administrators and Catholic

clergymen. It was only from the late eighteenth century on,

Between Two Empires 19

when the Austrian empire tried to modernize and centralize its

administration in order to halt the rise of nationalism, that the

Serbs had to face direct oppression from Vienna and Budapest?

In order to understand the development of vassalage and au-

tonomy among the Serbs after Kosovo it must be kept in mind

that the medieval Serbian state, nobility, and political institutions

did not immediately disintegrate after that momentous battle.

The battle was so costly to both sides that neither the victors

completely conquered nor were the vanquished completely de-

feated. Some of the surviving Serbian nobility in the south ac-

cepted the Sultan’s rule, maintaining their lands and privileges

in return for loyalty and military service. Thus they became vas-

sals of the Sultan rather than the Serbian tsar. They became

Christian sipahiler, part of the feudal cavalry of the Sultan’s army.

On a larger scale Tsar Lazar’s son and successor, Stefan

Lazarevi¢, made peace with the new sultan and became a vassal

prince, serving with Bayazid’s army at the battle of Ankara

against the forces of Tamerlane. The death of Sultan Bayazid at

Ankara in 1403 led to strife over the sultanic succession. This dis-

array among the Turks allowed Stefan Lazarevié¢ to restore, in

part, the territorial integrity and independence of his patrimony.

However, divisions among the Serbs, together with the restora-

tion of Ottoman power in the Balkans, led to a whittling away of

Serbian independence in the fifteenth century.

Juxtaposed between the rising Ottoman Empire and the pow-

erful Hungarian Kingdom, the Serbian rulers and nobility at-

tempted to perform a precarious balancing act to preserve their

autonomy. To do this, they at times aligned themselves with ei-

ther the Turks or the Magyars or they participated in movements

such as those of Skanderbeg and Jan Hunyadi. However, the end

of Hungarian power after the battle of Mohacs in 1526 left most

Serbs under Ottoman sway. A few remaining Serbian nobles

joined the remnants of the Hungarian nobility in giving their al-

legiance to the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor of Vienna.*

Thus most Serbs, who were peasants and herdsmen, came un-

der direct Ottoman rule in the period between the battles of

Kosovo (1389) and Mohacs (1526), but in most cases this rule was

not completely direct. Most Serbs, as well as other Christian sub-

jects of the Sultan, paid their taxes and fulfilled their feudal obli-

20 Serbia's Historical Heritage

gations through village headmen known as knezovi. By Muslim

law they could not bear arms and were obliged to pay an addi-

tional tax in lieu of military service. In some areas a form of im-

pressment or conscription known as the devsirme was practiced

to recruit Christian boys into the crack infantry units and the pal-

ace service of the Sultan. It was through the devsirme that many

Serbs, converted to Islam, and rose to high positions in the Otto-

man Empire. Among the most famous of these converts was the

Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokoli, brother of Makarije Sokolovié,

first Serbian Orthodox Patriarch of Pec.> With the exception of

the devsirme, the burden of the Serbian peasant under Ottoman

tule was less oppressive than that of most peasants in Europe

until the 17th century.

The burden was made less difficult by the existence or devel-

opment of social and political institutions on a local level which

protected individuals from the direct power of the state. The ex-

tended patriarchal family, the zadruga, the clan and the tribe in

some areas, provided solidarity and a sense of belonging to

weather the hardships of foreign rule. The development of self-

governing institutions on the village level with the knezovi and

village assemblies, together with the separate legal system of the

Serbian Orthodox Church, allowed for a limited degree of auton-

omy in many areas. This limited autonomy gave the Serbs the

wherewithal to retain a religious/cultural identity among the

common people of their past, through the church, epic poetry,

and folk customs.”

Certain communities, because of livelihoods, locations, mili-

tary service or other reasons, were able to retain even more au-

tonomy from Ottoman rule. Pastoral and border communities

who provided voynuklar and martoloslar (see below) for the Otto-

man army, as well as warrior communities such as Montenegro,

maintained an even greater degree of self-rule. Montenegro, be-

cause of its social organization based upon a tribal system, its

geographical inaccessibility, its proximity to areas under Vene-

tian control, and its inhabitants’ skill with arms, became de facto

independent by the 18th century.

As one can see in the above description of the factor of auton-

omy in Serbian survival, military power was an important ele-

ment in the creation and maintenance of autonomy. Military ser-

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Pavelic Papers PDFDocument2,090 pagesThe Pavelic Papers PDFeliahmeyer100% (4)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Najveci Zlocini Sadasnjice - Patnja I Stradeanje Srpskog Naroda U Nezavisnoj Drzavi Hrvatskoj Od 1941-1945 Dragoslav StranjakovicDocument584 pagesNajveci Zlocini Sadasnjice - Patnja I Stradeanje Srpskog Naroda U Nezavisnoj Drzavi Hrvatskoj Od 1941-1945 Dragoslav Stranjakovicvuk300100% (4)

- Sta Sam Video I Proziveo U Velikim Danima: Saopstenja Jednoga Prijatelja Iz Teskih Vremena RA RajsDocument284 pagesSta Sam Video I Proziveo U Velikim Danima: Saopstenja Jednoga Prijatelja Iz Teskih Vremena RA Rajsvuk30083% (6)

- Osvrt Na Popis Narodnosti U Jugoslaviji Lazo M KosticDocument151 pagesOsvrt Na Popis Narodnosti U Jugoslaviji Lazo M Kosticvuk30050% (4)

- Na Strasnom Sudu Radoje VukcevicDocument412 pagesNa Strasnom Sudu Radoje Vukcevicvuk300100% (7)

- Pregled Postanka Razvitka I Razvojacenja Vojne Granice - Od XVI Veka Do 1873 Godine Jovan SavkovicDocument176 pagesPregled Postanka Razvitka I Razvojacenja Vojne Granice - Od XVI Veka Do 1873 Godine Jovan Savkovicvuk30050% (2)

- Makedonsko Crkveno Pitanje Djoko SlijepcevicDocument107 pagesMakedonsko Crkveno Pitanje Djoko Slijepcevicvuk300100% (1)

- Crtice Iz Rata I Revolucije - Zbirka Objavljenih Dopisa Moji Dozivljaji 1941-1945 Godine Uros ZonjicDocument159 pagesCrtice Iz Rata I Revolucije - Zbirka Objavljenih Dopisa Moji Dozivljaji 1941-1945 Godine Uros Zonjicvuk3000% (1)

- Kroz Oganj I Suze - Pripovetke Jovan KonticDocument65 pagesKroz Oganj I Suze - Pripovetke Jovan Konticvuk300100% (2)

- Srpska Cetnicka Organizacija U Staroj Srbiji 1903-1908 - Terenska Organizacija Uros SesumDocument20 pagesSrpska Cetnicka Organizacija U Staroj Srbiji 1903-1908 - Terenska Organizacija Uros Sesumvuk300No ratings yet

- Momcilo Djujic I Vasilije Surlan - Dva Antipoda U Svestenickim Mantijama Radovan PilipovicDocument18 pagesMomcilo Djujic I Vasilije Surlan - Dva Antipoda U Svestenickim Mantijama Radovan Pilipovicvuk300No ratings yet

- Четници у Првом БалканскомРату 1912. Године - Урош ШешумDocument20 pagesЧетници у Првом БалканскомРату 1912. Године - Урош ШешумMarko RadenovicNo ratings yet

- Iz Minulih Dana - Gradja Za Istoriju Drugog Svetskog Rata Milorad JoksimovicDocument136 pagesIz Minulih Dana - Gradja Za Istoriju Drugog Svetskog Rata Milorad Joksimovicvuk300100% (7)

- Valvazor o Srpskim Uskocima Andra GavrilovicDocument22 pagesValvazor o Srpskim Uskocima Andra Gavrilovicvuk300100% (1)

- Londonski Pakt - Londonski Ugovor Glasnik SIKD Njegos KNJ 56-59Document59 pagesLondonski Pakt - Londonski Ugovor Glasnik SIKD Njegos KNJ 56-59vuk300No ratings yet

- Dolazak Uskoka U Zumberak Aleksa IvicDocument35 pagesDolazak Uskoka U Zumberak Aleksa Ivicvuk300No ratings yet

- Verni Hristu I Svetome Savi - Poboznost Srba Uskoka U XVII Veku Vladimir DimitrijevicDocument19 pagesVerni Hristu I Svetome Savi - Poboznost Srba Uskoka U XVII Veku Vladimir Dimitrijevicvuk300No ratings yet

- Srbi Za Vrijeme Urote Zrinjskoga I Frankopana Aleksa IvicDocument6 pagesSrbi Za Vrijeme Urote Zrinjskoga I Frankopana Aleksa Ivicvuk3000% (1)

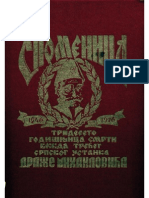

- Spomenica 1946-1976 - Tridesetogodisnjica Smrti Vozda Treceg Srpskog Ustanka Draze Mihailovica Organizacija Srpskih Cetnika Ravna GoraDocument446 pagesSpomenica 1946-1976 - Tridesetogodisnjica Smrti Vozda Treceg Srpskog Ustanka Draze Mihailovica Organizacija Srpskih Cetnika Ravna Goravuk300100% (3)

- Srpska Oslobodilacka Ideja Djoko SlijepcevicDocument78 pagesSrpska Oslobodilacka Ideja Djoko Slijepcevicvuk300No ratings yet

- Problem Unijacenja I Kroatizacije Srba Slavko GavrilovicDocument16 pagesProblem Unijacenja I Kroatizacije Srba Slavko Gavrilovicvuk300100% (2)

- Sistematsko Rasrbljavanje Svetosavske Crkve - Pravna I Politicka Razmatranja Lazo M KosticDocument124 pagesSistematsko Rasrbljavanje Svetosavske Crkve - Pravna I Politicka Razmatranja Lazo M Kosticvuk300100% (5)

- Otpor Marcanskoj Uniji Lepavinsko-Severinska Eparhija Dusan KasicDocument179 pagesOtpor Marcanskoj Uniji Lepavinsko-Severinska Eparhija Dusan Kasicvuk300100% (1)

- Istorija Unijacenja Srba U Vojnoj Krajini Johan Hajnrih SvikerDocument113 pagesIstorija Unijacenja Srba U Vojnoj Krajini Johan Hajnrih Svikervuk300100% (2)

- Hilandarsko Pitanje U XIX I Pocetkom XX Veka Djoko SlijepcevicDocument199 pagesHilandarsko Pitanje U XIX I Pocetkom XX Veka Djoko Slijepcevicvuk300No ratings yet

- Srpsko-Arbanaski Odnosi Kroz Vekove Sa Posebnim Osvrtom Na Novije Vreme Djoko SlijepcevicDocument441 pagesSrpsko-Arbanaski Odnosi Kroz Vekove Sa Posebnim Osvrtom Na Novije Vreme Djoko Slijepcevicvuk300100% (2)

- Bosna I Hercegovina Srpske Su Zemlje Po Krvi I Po Jeziku Vaso GlusacDocument87 pagesBosna I Hercegovina Srpske Su Zemlje Po Krvi I Po Jeziku Vaso Glusacvuk300100% (1)

- Uloga I Znacaj Vrbaske Banovine Stevan MoljevicDocument22 pagesUloga I Znacaj Vrbaske Banovine Stevan Moljevicvuk300No ratings yet

- The Macedonian Question Djoko SlijepcevicDocument269 pagesThe Macedonian Question Djoko Slijepcevicvuk300100% (2)