Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Meaney-Leckie Cashew Industry Ceara 1991 PDF

Uploaded by

Marcelo RamosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Meaney-Leckie Cashew Industry Ceara 1991 PDF

Uploaded by

Marcelo RamosCopyright:

Available Formats

The Cashew Industry of Ceará, Brazil: Case Study of a Regional Development Option

Author(s): Anne Meaney-Leckie

Source: Bulletin of Latin American Research , 1991, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1991), pp. 315-324

Published by: Wiley on behalf of Society for Latin American Studies (SLAS)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/3338673

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wiley and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of

Latin American Research

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Bull. Latin Am.Res.,Vo\. 10, No. 3, pp. 315-324, 1991. 0261-3050/91 $3.00 + .00

Printed in Great Britain. ? Society for Latin American Studies

Pergamon Press plc

The Cashew Industry of Ceara, B

Study of a Regional Developmen

ANNE MEANEY-LECKIE

Department of Geography, State University College ofNew York

USA

INTRODUCTION

The socio-economic underdevelopment ofthe Northeast region of

been a concern of the federal government for over 100 years

comprehensive development plan recommended agricultural and

reforms to alleviate the situation. Subsequent plans have affirmed t

An integral part of the reforms included the use of indigenous

resistant crops in the fostering of local agro-industries. This paper

the cashew industry as an example of one of these industries and lo

role in the socio-economic development of Ceara over the last 30 ye

is accomplished by assessing the growth of the industry, the

offered to assist growth, and the development of markets fo

products. Conclusions are drawn as to the usefulness of the ind

development option in terms of employment benefits, in-flow of c

the region and infrastructural expansion.

BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY

During the 1950s the Brazilian government recognised the und

ment of the Northeast as being the result of an unstable soc

situation, exacerbated, if not caused, by recurrent drought. A 1959

hensive development plan, A Policy for the Economic Developm

Northeast' (GTDN, 1959), recommended implementation of a re

would decrease the dependence of the Northeastern popu

subsistence agriculture in the drought-prone region by strengt

infrastructural, industrial and agricultural foundations of the Nor

the strength of this report an integrated regional development

formed, the Superintendencia do Desenvolvimento do Nordeste

the Superintendency of Development in the Northeast). SUDEN

unprecedented powers to co-ordinate the activities of the existi

ment agencies in the region as well as to formulate policies of its o

The objectives of SUDENE were to improve the regional infr

modify the agricultural system, relocate people to colonisation

the wetter areas of the Northeast, and bring industry into th

specific intention of the latter was to include the use of droug

crops of the sertao to foster local industrialisation efforts (Ro

109; Dickenson, 1978: 190). Shortly after the creation of S

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

316 BULLETIN OF LATIN AMERICAN RESEARCH

agency began, in particular, to promote industrial

Northeast through a series of fiscal incentives named a

which enacted the incentives in 1961. Under 434/18' Br

could reduce their tax liabilities by up to 50 per cent thr

in a fund established in the Banco do Nordeste do

Northeastern Brazil) and administered by SUDENE.

criteria applied by SUDENE, up to 75 per cent of th

build or revamp an existing plant could be obtaine

arrangement (Departmento de Industrializagao, 1970)

mined by the number of jobs created, the use of natur

existence of finished products that could be exported t

(Henshall and Momsen, 1976; Syrvund, 1974). There

processing, textile and oil-seed crushing industries tend

funding than the newly proposed chemical, electrical a

The former were viewed as more labour intensive and m

the needs of the sertao.

The 434/l 8' policy did succeed in attracting new industry to the Northeast,

diversifying the industrial structure and bringing in much needed capital,

despite the fact that it did not have the expected results in terms of employ-

ment (Henshall and Momsen, 1976; Kutcher and Scandizzo, 1981). 434/18,

was modified and improved over the years to meet the changing demands of

development. In December 1974, 434/18' was replaced by the Fundo do

Investimento do Nordeste (FINOR, Northeastern Investment Fund).

Operated by the BNB under SUDENE, FINOR's objectives were to secure

equal financing for the projects approved by SUDENE with effective

guarantees (see BNB, 1978).

SUDENE programmes in general came under fire after a severe drought in

1970 which illustrated that the programmes implemented in the previous

decade had little impact on the effects of the drought. As a result SUDENE

began to lose power in the 1970s and 1980s. However, other government

programmes were created to fill gaps. These programmes included the

Programa de Redistribugao de Terras e de Estimulo a Agroinditstria do Norte

e Nordeste (PROTERRA, Programme for Land Redistribution and Stimula-

tion of Agro-industry in the Northeast) which was designed to redistribute

land, but eventually became a line of credit, and POLONORDESTE

(Development Programme for Integrated Areas in the Northeast) which was

designed to create regional nuclei of development where technical and

financial services, industries and marketing co-operatives would be estab?

lished to help increase rural incomes. In addition, a series of five-year

national integration plans (PIN, Plano de Integraqao Nacional) beginning in

1970 have sought to ensure the basic goals of SUDENE: development ofthe

regional infrastructure, modifying the agricultural system, colonising the

moist margins of the region and industrialisation.

THE CASHEW AS A DEVELOPMENT OPTION

The primary thrust ofthe early SUDENE years was industrialisation.

end a significant effort was made to modernise the textile industry, t

refineries, the tanneries and the oil-seed refineries. However, in add

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE CASHEWINDUSTRY OF CEARA, BRAZIL 317

promoting the traditional industries there was an effort to discover and foster

additional local agro-industries. It was argued that local drought-resistant

crops, particularly those easily processed locally, requiring little capital

investment, using a large portion of both the rural and urban labour force, for

which a lucrative market for the final product could be found, would

contribute significantly to the efforts to industrialise the Northeast. It was

also argued that such industrialisation would serve to decrease the flow of

capital out of the region and improve the local infrastructure (Instituto de

Planejamento, 1974).

In the late 1950s an increase in foreign demand for the cashew kernel and

the consequent increase in the global price of kernels created an optimal

enterprise for SUDENE funding. The cashew tree was indigenous, drought

resistant and grew in natural stands along the coasts of the Northeastern

states of Ceara and Rio Grande do Norte (see Fig. 1) on land too poor to

support subsistence food crops. In addition, the tree yielded three products

that could be commercialised: the cashew kernel, CNSL (Cashew Nut Shell

Map by Brian Okey

FIG 1 Location map ofCeard

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

318 BULLETIN OF LATIN AMERICAN RESEARCH

Liquid), and the peduncle. Each of these products could

ised because little capital investment was required and t

mechanised processing equipment could be 'hom

anticipated that because of the nature of the process

manual harvesting required, significant portions of bot

populations could be employed on a semi-permanent

their vulnerability to drought.

Through the incentives provided by 434/18\ FIN

programmes, all facets of the cashew industry have gr

years, albeit with some difficulty in matching industria

production. Ninety per cent of the cashews on the wor

grown and processed in Northeastern Brazil, primarily

In order to evaluate the potential of the cashew industry

plan for socio-economic stability and development in th

now goes on to address the growth of the industry, the

assist growth, and the development of markets for cas

THE GROWTH OF THE CASHEW INDUSTRY

Indigenous stands of cashew trees along the Northeastern coast of

were used by natives for food and medicinal purposes. After colonisa

the area in the mid-1500s, the tree was cultivated by European settler

the kernel was used by navigators as a reserve food source on long vo

(Lery, 1770). Through this process the cashew was disseminated t

tropical areas in the world, specifically East Africa and India. Desp

diffusion, cultivation and processing techniques remained rudimentar

commercialisation limited, until the 1940s.

During World War II, in return for technical assistance in aviat

general industrialisation, the Brazilian government allowed the United

of America to run a series of expeditions in search of raw materials th

be used in the war effort. During this time modern uses for CN

discovered, and the world became more familiar with the taste of the

kernel.

CNSL is one of the few natural and economic sources of phenol, an

alcohol that is poisonous when taken internally and causes deep burns

it comes in contact with the skin. Traditionally, the natives used

antiseptic and as a treatment for skin diseases such as ringworm. How

testing in the 1940s showed that CNSL could be used as a synthesising

in forming other chemical compounds, particularly substitutes f

various derivatives of petroleum (Holanda, 1971). Therefore, it was us

the war effort as a petroleum substitute in ammunition, rubber, and

essential materials.

In 1943 a partially American-owned firm, Brasil Oiticica, began manu-

facturing CNSL in Fortaleza, Ceara. The manner of processing also used the

kernel, which, when roasted and salted, sold well on the international market.

By 1945 Brasil Oiticica had secured the American cashew kernel market

from potential competitors in India and East Africa. This was primarily

because of a US federal regulation that required that CNSL be extracted and

made available to the USA before any kernels were imported. The distance,

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE CASHEW INDUSTRY OF CEARA, BRAZIL 319

the peril of the wartime seas, and the rudimentary nature of the industry i

India and Africa prevented them from becoming major suppliers (Estev

1961).

After the war the demand for CNSL fell, but as the world economy

recovered demand for the kernel as a delicacy food rose. Brasil Oiticica and

other vegetable-processing industries realised the potentially larger market

and increased their production of kernels. Through a series of contracts with

local farmers the harvest of existing stands was intensified. For example, the

average yield of 100 hectares in 1958 was 31,481 kilogrammes of fruit, and

by 1961,45,462 kilogrammes (IBGE, 1958,1961). In the late 1950s several

small experimental plantations of cashews were established in an effort to

increase the supply of raw materials. In fact, the state government had a

standing offer of free seeds to anyone willing to cultivate cashews (Caval-

cante and Neto, 1973). However, because the tree takes 7-8 years to mature,

the investment in land and cultivation equipment was too costly for many

individuals or firms to undertake. Between 1960 and 1968, for example, only

10,000 hectares of cashews were planted while in the same period the num?

ber of processing industries increased from 2 to 17. This latter was largely in

response to the industrial incentives offered by '34/18'.

Finally, in 1968 both the government agencies and the industry agreed that

only large, well-organised plantations could begin to provide the necessary

raw material and avert a production crisis (Johnson, 1972). The concept of

vertically integrated firms was encouraged, and most of the processing firms

established their own plantations. By the end of 1972,182,000 hectares had

been approved for financing, but less than half were ever planted (Cavalcante

and Neto, 1973).

A production crisis was not averted because the government continued to

provide financial incentives for the establishment of processing plants and,

because the cashew industry was considered a priority, industrialists were

able to receive up to 75 per cent funding from 434/18\ By 1987 there were

24 processing plants in operation in Fortaleza, all of which were operating at

less than 50 per cent capacity and several at a fiscal loss.1 This unequal

funding of the industry and plantations decreased efficiency of the former.

During the 1980s five processing plants in Fortaleza were forced into bank?

ruptcy because of a lack of raw materials.2

Despite such setbacks the industry continues as a priority for government

funding primarily because buoyant international demand keeps the price of

the product high. In response to the production shortage in Northeast Brazil,

the world price for cashew kernels leapt from $900/tonne in 1966 to $2500/

tonne in 1975 and reached almost $5000/tonne in 1978 (Instituto de

Planejamento, 1974; Meaney, 1980). The 50 per cent increase between

1975 and 1978 was due to a lack of raw materials because the plantations

implemented after 1968 had not yet come into production. It was also a time

when the only other international producer of cashews, Mozambique, was

experiencing political turmoil. The price stabilised in the 1980s as produc?

tion increased, and by the late 1980s one tonne of cashew kernels was

approximately priced at $6200 (IBGE, 1987a).

It should be noted that in addition to the demand for cashew kernels, the

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

320 BULLETIN OF LATIN AMERICAN RESEARCH

world demand for pure CNSL began to rise again

petroleum prices soared and new uses for CNSL

CNSL can be found in over 200 US patented item

linings and electrical wiring to plastics, insecticid

sequence the demand and price have begun to rise

1973 and 1980 there was a 57 per cent increase in

and a 200 per cent increase in the price (Meaney, 198

Brazilian industrialisation for commercial production

that use CNSL is in the distant future. Many of the p

and Brazil currently lacks the industrial linkages nec

work entailed.

Always popular on the regional level, demand for p

as fruits, juices, pastes and jellies is increasing on th

for example, cashew pastes accounted for 7 per cent o

national market. However, when compared to guava a

64 and 25 per cent ofthe market, respectively, it is

demand for peduncle products is limited (Instituto d

Peduncle products have yet to become popular on int

make up only about 2 per cent of the tropical fruit ex

The cashew industry then, received and continues t

government incentives to develop because it uses

which is easily industrialised within the region for w

has been developed and maintained.

THE INDUSTRY AS A SOCIO-ECONOMIC STABILISER

The primary motivation behind the government's industrial and agr

incentive programmes was to bring socio-economic stability to the p

stricken region. It was argued that if the reliance of the population

vagaries of subsistence agriculture in the drought-prone Northeast c

reduced by the establishment of permanent jobs not affected by rec

drought, then the region could begin to develop and present less of a

the national coffers. In addition, the incentives would provide an inf

capital and improve local infrastructure. The establishment of th

industry in the region was one means of addressing the concern

government and the data indicate that this has been largely successf

Employment

Traditionally the population most vulnerable to drought-related problems

are the subsistence agriculturalists in the interior. During times of severe

drought much of this population becomes migratory and, in the twentieth

century, has either joined government public 4work-fronts' if positions were

available, or entire families, or parts of families, have migrated to the coastal

cities in search of work. The development of vertically integrated industries

such as the cashew, which function regardless of drought conditions and

employ portions of both the rural and urban labour forces in Ceara, have

helped break this cycle.

The cashew plantations, 90 per cent of which are located between

Beberibe and Mossoro (see Fig. 1), offer a variety of jobs at different stages of

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE CASHEW INDUSTRY OF CEARA, BRAZIL 321

their development. During the early years, labour is required to clear, plant,

and maintain the land. In addition, most plantations are intercropped wit

annual cash crops to generate income for the first years and to provide food

for the workers. Usually intercrops are removed once the plantation is in ful

production because the income they provide is no longer necessary. How

ever, more recently some FINOR financing has required that the intercrops

be continued or alternative land be made available for subsistence crops t

be grown for workers (Meaney, 1980).

A large plantation requires a high concentration of unskilled labour for

3-5 month period during the harvest. This labour force is usually made up of

women and children who often migrate between plantations. Cavalcante and

Neto (1973:90) estimated that by 1987-1988, when plantations were in fu

production, approximately one-quarter of the rural population over the ag

of five between the towns of Mossoro and Aracati (see Fig. 1) would be

employed on them (see Meaney, 1980). The 1989 production figures show

that 58,685 tonnes of cashew nuts were harvested in Ceara and 47,275

tonnes in Rio Grande do Norte (IBGE/CEPAGO, 1990: 33). The tota

number of people employed in harvesting in these two states then was

approximately 40,000. In addition to the above-mentioned figures, a smaller

number of permanent jobs in caretaking and maintenance are available fo

men on the plantations. It has also been shown that these jobs have not been

affected by droughts (see DNOCS, 1985).

The cashew processing plants also employ a large number of people. In

1960 the two processing plants in existence employed about 600 people.

Today the 24 nut-processing firms employ about 17,000 people. In

addition there are 17 fruit-processing firms that have over one-half of their

production in peduncle products and employ about 1500 people. Th

entire cashew processing industry, then, employs just under 20,000 peopl

or 25 per cent of the industrial workers employed in Ceara (IBGE, 1987b

483). Ninety per cent of the employees in the cashew industry are women

drawn from the urban poor who live on the outskirts of the city. They come

primarily from families who have fled the interior in the face of drough

and are classified as 'unskilled' (Cavalcante and Neto, 1973: 91; Meaney,

1980).

The cashew industry, then, has served to employ sectors of the urban and

rural population who traditionally have been either vulnerable to drought or

lacked the skills necessary for employment in an urban setting.

Capital investments

The '34/18' and FINOR incentives encouraged investment in Northeastern

Brazil by offering tax advantages and supplementary funding. A number of

large firms took advantage of these offers and became involved in cashew

ventures in the Northeast as tax shelters (Cavalcante and Neto, 1973; Pessoa

and Carneiro, 1978). This allowed for an influx of capital into the region that

otherwise is unlikely to have materialised. The income generated by the

industry has encouraged local entrepreneurs to stay in the region and to

reinvest profits in other development opportunities, such as the vertical

integration of cashew processing plants with plantation development. Thus,

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

322 BULLETIN OF LATIN AMERICAN RESEARCH

the tendency for profits to be filtered out of the region to

is reduced, the gross regional income is increased, and th

economy is encouraged. There have also been several '

particularly in the processing of other tropical fruit

passion fruit.

Infrastructural improvements

Because of already existing port facilities in Fortaleza the city has become the

export centre for cashew products in Northeastern Brazil. The international

market associated with the cashew kernel and CNSL has increased the use of

these facilities and has played a role in decisions for their improvement. The

city has also become the major processing centre primarily because of the

existence ofthe port and early industries, but also because ofa transportation

network that converges on Fortaleza from the interior, and the existence of a

major coastal highway.

The two-lane, all-weather, highway connects Fortaleza with the main

cashew plantation areas south of Mossoro, and beyond, and facilitates the

transport of raw materials to the plants. There has also been spontaneous

development of cashew plantations along this stretch of road in the last

10 years due to ease of transportation. The industry has also been a

significant factor in the bettering ofthe transport and communication system

from Fortaleza west to Pacajus (see Fig. 1) where four major cashew planta?

tions have been established since 1978. The existence of these improved

transportation and communication facilities has also served to decrease the

vulnerability of the population in the interior to drought because relief aid is

much more easily distributed. The cashew industry then has assisted in, and

taken advantage of, the infrastructural improvements in the region.

CONCLUSIONS

The comprehensive development plan implemented in Northeast

1959 had as its base a reform that would decrease the effect of recurrent

drought on the population and increase the standard of living through

agricultural reform, industrial development and relocation schemes. Since

that time many projects in all three of these categories have been imple?

mented with varying degrees of success. In terms ofthe projects implemented

to foster local industries in the region few have met the development

objectives as well as the cashew industry. Dickenson (1978), for example,

notes that efforts to establish steelworks and a synthetic rubber factory based

on cane alcohol were both delayed. He also notes that although there was

tremendous potential for revitalising the textile industry, the end-product

was a loss of 20,000 jobs between 1960 and 1970 (ibid.).

The cashew industry, on the other hand, has grown beyond the original

expectations of the planners, primarily because of a strong international

demand and the multiplicity of products. It is important, therefore, that both

these factors be taken into consideration when translating the success of the

cashew industry to potentials for other industries. The ability of the kernel

market, for example, to absorb rapid price increases without deteriorating is

not a factor that would necessarily be true with other agro-products. Nor

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE CASHEWINDUSTRY OF CEARA, BRAZIL 323

would many fledgling industries be able to sustain the internal mism

ment that resulted in a lack of raw materials and an excess of installed

capacity in the factories.

However, it could be argued that some of the success of the cashew

industry in providing employment for the rural and urban poor, in helping to

impro ve the regional infrastructure, and increasing the flow of capital into the

region, could be translated to the development of other crops. Fruit crops,

such as guava and passion fruit, with growing international market value, are

certainly possibilities. The increase in the number of fruit-processing plants

in Fortaleza in the last 10 years indicates a trend in this direction. One could

also argue for the revitalisation of the oil-seed industry, if increased demand

could be created for its products. It is also evident that there is a need for

further study into secondary products that may be derived from a single

plant, thus increasing the market value of the crop.

NOTES

1. Personal communication, T. A. Falcao, cashew exporter, Fortaleza, Ceara.

2. Personal communication, M. Rodriguez, Banco do Nordeste do Brasil.

REFERENCES

BANCO DO NORDESTE DO BRASIL (BNB) (1978), Fundo do Investimento d

Banco do Nordeste do Brasil (Fortaleza).

CAVALCANTE, R. N. and NETO, A. L. (1973), Agroindustria do Caju no Norde

Nordeste do Brasil (Fortaleza).

DEPARTAMENTO DE INDUSTRIALIZA^AO (1970), Sistemdtica de Apli

Recursos dos Artigos 34/18 com as Alteragoes 65970/69, SUDENE (Recife).

DICKENSON, J. (1978), Studies in Industrial Geography: Brazil, Westview Pres

DNOCS (1985), A Situagdo Socio-economica da Seca, DNOCS (Fortaleza).

ESTEVES, A. B. (1961), Industrializagdo da Castanha de Caju Produzida no

Portugues, Missao de Estudos Agronomicas do Ultramar (Lisbon).

GRUPO DE TRABALHO PARA O DESENVOLVIMENTO DO NORDE

(1959), Uma Politica deDesenvdlvimentopara oNordeste, Conselho de Desen

(Rio de Janeiro).

HENSHALL, J. and MOMSEN, R. P. (1976), A Geography ofBrazilian Developm

and Sons (London).

HOLANDA, L. (1971), 'Caracteristicas Fisicas e Quimicas do Caju', Ciengia A

115-120.

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFlA E ESTATfSTfCA (IBGE) (1958-1987a),

Anudrio Estatistica, IBGE (Rio de Janeiro).

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFf A E ESTATfSTfCA (IBGE) (1987b), Produ

Agricola Municipal: Tomo I: Norte e Nordeste, IBGE (Rio de Janeiro).

IBGE/CEPAGO (1990), Levantamento Sistemdtico da Produgdo Agricola, IBGE (Rio d

Janeiro).

INSTITUTO DE PLANEJAMENTO (1974), Projeto de Desenvdlvimento de Agroindustria no

Nordeste: Projeto Caju, Secretaria de Planejamento da Presidencia da Republica (Brasilia).

INSTITUTO DE PLANEJAMENTO (1987), Projeto de Desenvdlvimento de Agroindustria no

Nordeste: Projeto Caju, Abacaxi, Maracujd, Secretaria de Planejamento da Presidencia da

Republica (Brasilia).

JOHNSON, D. (1972), The Cashew Industry of Northeast Brazil: a Geographical Study ofa

Tropical Tree Crop, University Microfilms (Ann Arbor, Michigan).

KUTCHER, G. and SCANDIZZO, P. (1981), The Agricultural Economy of Northeast Brazil,

Johns Hopkins University Press (Baltimore).

LERY, JEAN DE (1770), Histoire d'un voyagefait en la terre du Bresil, Paris: Vol. I.

This content downloaded from

15ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

324 BULLETIN OF LATIN AMERICAN RESEARCH

MEANEY, A. (1980), The Cashew Industry of Ceard, Brazil, Universit

Arbor, Michigan).

MINISTERIO DO INTERIOR (1959), Programa do Desenvolvimento do

(Rio de Janeiro).

P?SSOA, L. and CARNEIRO, M. (1978), A Agroindustria de Caju no Cear

Investimentos, Fundagao Instituto de Planejamento do Ceara (Fortaleza

ROBOCK, S. (1963), Brazil's DevelopingNortheast, Brookings Institution

SYRVUND, D. (1974), Foundations of Brazilian Economic Growth, Hoov

(Stanford).

This content downloaded from

152.3.102.254 on Wed, 22 Jul 2020 12:14:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Gender, Generation, and Personal Destinies, Histories of Women and Men Textile Workers in Bahia, Brazil - Cecilia Maria Bacellar SardenbergDocument38 pagesGender, Generation, and Personal Destinies, Histories of Women and Men Textile Workers in Bahia, Brazil - Cecilia Maria Bacellar SardenbergMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Stevenson2016 - The Women's Movement and Class Struggle' Gender, Class Formation and Political Identity in Women's Strikes, 1968-78Document16 pagesStevenson2016 - The Women's Movement and Class Struggle' Gender, Class Formation and Political Identity in Women's Strikes, 1968-78Marcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Marcel Van Den Linden-Workers of The WorldDocument477 pagesMarcel Van Den Linden-Workers of The WorldDasten Julián100% (1)

- Claudia Jones - We Seek Full Equality For WomenDocument6 pagesClaudia Jones - We Seek Full Equality For WomenMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Oral History, Identity Formation and Working-Class Mobilization - John French and Daniel JamesDocument17 pagesOral History, Identity Formation and Working-Class Mobilization - John French and Daniel JamesMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Megaphone Working: The of and Class: University CanterburyDocument20 pagesMegaphone Working: The of and Class: University CanterburyMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Gender, Generation, and Personal Destinies, Histories of Women and Men Textile Workers in Bahia, Brazil - Cecilia Maria Bacellar SardenbergDocument38 pagesGender, Generation, and Personal Destinies, Histories of Women and Men Textile Workers in Bahia, Brazil - Cecilia Maria Bacellar SardenbergMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Eaton Rural-Urban Migration and Women 1992 PDFDocument12 pagesEaton Rural-Urban Migration and Women 1992 PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Webb Paragraph On Fortaleza Food Supply 1961Document11 pagesWebb Paragraph On Fortaleza Food Supply 1961Marcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Meaney-Leckie Cashew Industry Ceara 1991 PDFDocument11 pagesMeaney-Leckie Cashew Industry Ceara 1991 PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Gondim Fortaleza Social Inequality Design Politics 2004 PDFDocument19 pagesGondim Fortaleza Social Inequality Design Politics 2004 PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Lima Industrial Work Force Fortaleza 1975 PDFDocument8 pagesLima Industrial Work Force Fortaleza 1975 PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Lima Industrial Work Force Fortaleza 1975 PDFDocument8 pagesLima Industrial Work Force Fortaleza 1975 PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Gondim Fortaleza Social Inequality Design Politics 2004 PDFDocument19 pagesGondim Fortaleza Social Inequality Design Politics 2004 PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Eaton Rural-Urban Migration and Women 1992 PDFDocument12 pagesEaton Rural-Urban Migration and Women 1992 PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Emilia Viotti Da CostaDocument22 pagesEmilia Viotti Da CostaMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- French - James Oral History 1997Document17 pagesFrench - James Oral History 1997Marcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Vansina Oral Tradition As History 1985 3-32 & 33-201Document32 pagesVansina Oral Tradition As History 1985 3-32 & 33-201Marcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Dias Martins State Modernization Agrarian Reform 1998Document26 pagesDias Martins State Modernization Agrarian Reform 1998Marcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Jarusch - Coclanis Quantitative History 2015Document5 pagesJarusch - Coclanis Quantitative History 2015Marcelo Ramos100% (1)

- History From BelowDocument6 pagesHistory From BelowFiorenzo IulianoNo ratings yet

- When The Plumber(s) Come To Fix A Country: Doing Labor History in BrazilDocument10 pagesWhen The Plumber(s) Come To Fix A Country: Doing Labor History in BrazilMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Tomo V Vol 2 As Torturas PDFDocument899 pagesTomo V Vol 2 As Torturas PDFMarcelo RamosNo ratings yet

- Thomas E. Skidmore-The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil, 1964-1985-Oxford University Press, USA (1988) PDFDocument433 pagesThomas E. Skidmore-The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil, 1964-1985-Oxford University Press, USA (1988) PDFMarcelo Ramos100% (2)

- Tomo V Vol 3 As TorturasDocument955 pagesTomo V Vol 3 As TorturasAluizio Ferreira Palmar0% (1)

- Tomo IV As Leis RepressivasDocument126 pagesTomo IV As Leis RepressivasAluizio Ferreira PalmarNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Tle 9 Q3 W1 WordDocument7 pagesTle 9 Q3 W1 WordPeter sarionNo ratings yet

- Student (Mechanical Engineering), JECRC FOUNDATION, Jaipur (2) Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, JECRC FOUNDATION, JaipurDocument7 pagesStudent (Mechanical Engineering), JECRC FOUNDATION, Jaipur (2) Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, JECRC FOUNDATION, JaipurAkash yadavNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law Syllabus 2014 2015Document5 pagesEnvironmental Law Syllabus 2014 2015valkyriorNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Ancient Rome On Wine HistoryDocument30 pagesThe Influence of Ancient Rome On Wine Historynevena_milinovic100% (1)

- Dhruvi Project Chap 2Document10 pagesDhruvi Project Chap 2Dhruvi PatelNo ratings yet

- Plantation News Flow 210202Document3 pagesPlantation News Flow 210202Brian StanleyNo ratings yet

- RONA'S AGRI Supplements Store: Ronalyn B IlagDocument9 pagesRONA'S AGRI Supplements Store: Ronalyn B Ilagrhina Ilag100% (1)

- ChickpeaDocument125 pagesChickpeaAashutosh BhaikNo ratings yet

- M4 Bid Limestone Site DevtDocument12 pagesM4 Bid Limestone Site DevtAlmario SagunNo ratings yet

- 11 Test 1plant KingdomDocument3 pages11 Test 1plant KingdomJaskirat SinghNo ratings yet

- PackageA SampleDocument12 pagesPackageA SampleAshraf IskandarNo ratings yet

- 3.6 Nutrient Management - Key Check 5Document44 pages3.6 Nutrient Management - Key Check 5janicemae100% (2)

- PESTL Analysis Yakult (Section B, Group 3)Document13 pagesPESTL Analysis Yakult (Section B, Group 3)Ammar Al-kadhimiNo ratings yet

- Conservation AgricultureDocument22 pagesConservation AgricultureChinmoyHait100% (2)

- Unconsolidated Undrained Triaxial Test On ClayDocument16 pagesUnconsolidated Undrained Triaxial Test On Claygrantyboy8450% (2)

- ID Analisis Risiko Kesehatan Lingkungan PenDocument9 pagesID Analisis Risiko Kesehatan Lingkungan PenFarikhNo ratings yet

- Biotricks Biotech, Nashik: MissionDocument5 pagesBiotricks Biotech, Nashik: MissionSantosh TalegaonkarNo ratings yet

- Determinationofseedmoisture Usharani 170731103129Document32 pagesDeterminationofseedmoisture Usharani 170731103129Sabrina CruzNo ratings yet

- Wildlife Fact File - Mammals, Pgs. 181-190Document20 pagesWildlife Fact File - Mammals, Pgs. 181-190ClearMind84100% (1)

- Indigo RevoltDocument3 pagesIndigo Revoltsangeetasarkar0509No ratings yet

- What Is Kosher FoodDocument9 pagesWhat Is Kosher FoodAnonymous oRIJYGumNo ratings yet

- Growing Kiwifruit: PNW 507 - Reprinted September 2000 $2.50Document24 pagesGrowing Kiwifruit: PNW 507 - Reprinted September 2000 $2.50conkonagyNo ratings yet

- Study of Value Chain and Value Additive Process of NTFP'S Like Tamarind in Indian States Aneesh Ghosh 20125010 MBADocument7 pagesStudy of Value Chain and Value Additive Process of NTFP'S Like Tamarind in Indian States Aneesh Ghosh 20125010 MBAAneeshGhoshNo ratings yet

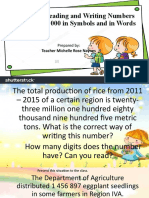

- Read and Write Numbers Up To 10 000 000 in Symbols and in WordsDocument13 pagesRead and Write Numbers Up To 10 000 000 in Symbols and in WordsMichelle Rose NaynesNo ratings yet

- Faith Agric - ss1Document4 pagesFaith Agric - ss1r14919068No ratings yet

- About KirloskarvadiDocument4 pagesAbout KirloskarvadiKamlesh DeorukhkarNo ratings yet

- APEDADocument8 pagesAPEDAArpit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Acid Alkaline FoodsDocument31 pagesAcid Alkaline Foodsannu124100% (9)

- Self-Propelled Uniport 2000 PlusDocument8 pagesSelf-Propelled Uniport 2000 PlusMarceloGonçalvesNo ratings yet

- National Forest Policy ComaparisonDocument28 pagesNational Forest Policy ComaparisonYogender Sharma100% (1)