Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ContentServer 7 PDF

Uploaded by

ali abtalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ContentServer 7 PDF

Uploaded by

ali abtalCopyright:

Available Formats

Commerce, E-Commerce, and M-Commerce:

What Comes Next?

Zakaria Maamar

In ancient times, people exchanged their goods and services to obtain what they

needed (such as clothes and tools) from other people. This system of bartering com-

pensated for the lack of currency. People offered goods/services and received in kind

other goods/services. Now, despite the existence of multiple currencies and the

progress of humanity from the Stone Age to the Byte Age, people still barter but in a

different way. Mainly, people use money to pay for the goods they purchase and the

services they obtain.

Commerce

Notwithstanding the technologies that are involved, undertaking commerce can be asso-

ciated with one of the four types of exchange: bargaining, bidding, auctioning, and clear-

ing [3]. The first two types of exchange are bilateral and the last two types of exchange

are trilateral (that is, a third party intervenes).

• Bargaining involves one user that negotiates with a provider until an agreement

between both is reached. First, the user looks for a provider, browses their products,

and then negotiates with the provider for an agreement. If the negotiation fails, the user

continues searching for other providers until an agreement with one of them is

reached.

• Bidding involves one user and several providers. First, the user calls for bids.

Next, the user compares the offers that providers have submitted after receiving

the call for bids. Finally, the user selects the provider that has made the lowest

offer (that is, the offer that minimizes the user’s expense).

• Auctioning (English scenario) involves one provider, several potential users, and

one broker. First, the provider fixes the lowest price of the product. Through the

broker, the provider advertises their products and calls for auctions. Next, the dif-

ferent users respond to the call for auctions by making offers to the broker. Act-

ing on the provider’s behalf, the broker selects the user who has made the highest

offer regarding the first offer of the provider (that is, the user’s offer maximizes

Zakaria Maamar (zakaria.maamar@zu.ac.ae) is an associate professor at Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab

Emirates.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies

are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy

otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee.

© 2003 ACM

COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM December 2003/Vol. 46, No. 12ve 251

the provider’s income). Besides the English scenario of auctioning, Dutch and

Vickrey also exist as additional scenarios of auctioning.

• Clearing involves several users, several providers, and one broker. Users and

providers submit their respective requests to the broker in terms of needs to sat-

isfy for the users and services to offer for the providers. The role of the broker is

to match needs to services. If there is a successful match, the broker notifies both

users and providers about the match. As soon as they are informed, users and

providers start interacting together, bypassing the broker.

E-Commerce

The Internet and Web technologies have tremendously changed the way of doing

business in general, and commerce in particular. Users have more opportunities to be

informed about the current trend of the market before making any decision. Users are

continuously browsing the Internet as well as being overwhelmed with information

from different online sources (for example, money.cnn.com/). In addition, there is no

longer any need to go to a library to purchase one’s favorite sports magazine. Several

Web sites exist that allow users to submit online orders. This way of doing business

constitutes a part of what is commonly known as e-commerce). Web shopping is only

a small part of the whole e-commerce picture that covers several types of businesses

that range from customer-based retail sites like Amazon.com (business-to-consumer),

to auction and music sites like eBay, and to business exchanges trading goods/services

between corporations (business-to-business). E-commerce is seen as a general term for

any type of business, or commercial transaction, that involves the transfer of infor-

mation across the Internet.1

E-commerce puts new demands not only on support and delivery IT, but also on

the way business processes have to be designed, deployed, and maintained. Several

people in different locations and with different hardware and software resources may

simultaneously initiate purchase requests for the same product but with different

selection criteria. Reliability, efficiency, scalability, and fault-tolerance are among the

features that should be embedded in e-commerce processes. To assess the value-added

of these processes, it is crucial to be aware of their type. Processes that help potential

customers, whether individuals or businesses, in locating the goods/services they need

are essential. At the same time, processes that allow suppliers to make customers

aware of their products are also important. At the present time, Web sites are full of

advertising banners that enable users to enter and visit provider sites with one click

(for example, shopping.netscape.com/main.adp).

E-commerce as part of the whole e-business evolution has been the object of

major changes [3]. First, businesses started the digitalization of their data to make it

available online. This data included the business’s profile and catalogues. Initially,

businesses did not attempt to adapt their business processes (that is, the know-how).

Later, businesses decided to undertake the reengineering of their processes due to the

pressure to remain competitive. The traditional way of satisfying users’ needs could

no longer cope with the challenges presented by the new context with its complex fea-

tures: profitability, competition, alliances, and market volatility. Adjusting the busi-

ness’s know-how to the context, therefore, became critical. The third stage consisted

1

E-commerce FAQ; ecommerce.about.com/library/weekly/aa21502a.htm?PM=ss11_ecommerce (visited July 2002).

252 December 2003/Vol. 46, No. 12ve COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM

of offering online forms to capture users’ needs efficiently and accurately. There was

no longer the need to send faxes or call vendors to get orders completed. To conclude

any purchase transaction, financial partners were invited to join the shopper-vendor

relationship. Ensuring the security of the payment process and the exchange of pri-

vate information was and still is a major concern. The next stage in the e-business

evolution was the offering of personalized services. The purpose of personalized serv-

ices is to include the profiles of users in terms of preferences and interests when work-

ing to fulfill their needs. Now, the trend of e-business is towards joint ventures where

business processes are merged.

Despite the growing number of e-commerce sites, conducting e-commerce oper-

ations is still challenging. Various obstacles exist. First, relevant Web sites with access

to catalogues have to be discovered. Second, the way these sites operate has to be

understood. Third, needs have to be specified according to the characteristics (termi-

nology) of the sites. Last but not least, security problems can occur when sensitive

information is submitted. Many times, obstacles that face novice users upset them

and the whole e-shopping experience ends in frustration. Instead of supporting users,

IT is making things more complex. As a direct consequence, users may simply turn

to the competition or decide to go back to the traditional way of shopping: ask friends

to accompany them, visit shops, talk to vendors, and bargain for better deals. It

should be noted that once IT is introduced into the process, the “social context” is

ignored. One of the challenges that needs tackling in the near future is how to inte-

grate the social context into the development of any user-oriented systems. Schum-

mer argues that while e-commerce applications aim at easing the process of shopping

by simulating real world experiences, these applications unfortunately do not include

social factors in their simulation [4]. Users are mainly kept separated and everyone is

shopping as if they were alone in an empty store. A survey done in Schummer

reported the importance of the social factors and showed that 90% of shoppers pre-

fer to communicate while shopping [4]. Furthermore, according to Kraft, Pitsch, and

Vetter, the current malls on the Internet are characterized by a 2D representation,

navigation according to links, single-user environments, and static environments that

lack realism and interactivity [2]. In contrast, the shopping process in real life is def-

initely a social one where people can get advice and share their experiences with oth-

ers. To deal with some of the obstacles to e-commerce, several experimental

technologies (for example, software agents, Web services) that aim at supporting

users are now available. The purpose of these technologies is to attract more con-

sumers and encourage them to participate in online business.

M-Commerce

It is acknowledged that the Internet is playing an important role in our daily life. The

Internet has become a vehicle for services rather than just a static repository of infor-

mation. Airline booking and hotel booking are examples of these services. Besides the

new role of the Internet, we are witnessing rapid progress in wireless and handheld tech-

nologies. Telecom companies are offering new opportunities to users over mobile

devices like cellular phones and personal digital assistants. Reading emails and sending

SMS messages between cellular phones are becoming natural. Surfing the Web thanks

to the Wireless Application Protocol is further evidence of the wireless technology devel-

opment. We are convinced that the next stage (if we are not already in it) for telecom

COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM December 2003/Vol. 46, No. 12ve 253

companies in partnership with businesses is to allow users to buy and sell without being

connected to any wired network. Mobile commerce (m-commerce) is the new trend and

is expected to drive the future development of e-commerce.

Being able to buy and sell goods/services over mobile devices is an important step

towards achieving an anywhere, anytime paradigm. Location and time will no longer

constrain people from completing their transactions. Suppose that a person would

like to buy a gift for her son’s birthday while she is on a bus. Instead of postponing

the errand, she can use her mobile phone to search for the perfect gift. Her search can

be narrowed by such criteria as the maximum price she is willing to pay, the desired

delivery time, and the age of her son. It would be even more interesting if this person

could outsource the entire transaction to intelligent components that could act on her

behalf. Software agents are among the components that will have an important role

to play in the worldwide spread of m-commerce.

An e-commerce value-chain represents a set of business processes that implement

interactions between online shoppers and e-commerce systems. Song and Whang

suggested a value chain of eight processes: attract, interact, customize, transact, pay,

deliver, service, and personalize [5]. Applying the above value chain to m-commerce

requires an adjustment to the processes because of the features of wireless communi-

cation channels and mobile devices. Communication channels are unwired and suf-

fer from latency and low bandwidth. Devices are also unwired and suffer from low

computing resources and small screen sizes. Following is an explanation of the

processes that would require adjustment based on the features of m-commerce:

• Attract: because users of mobile devices are not attached to any physical location,

their location at a specific time can be used to identify the businesses that are in

the users’ area and have special offers. Being aware of the users’ interests and pref-

erences ensures that users receive relevant offers according to their profile.

• Interact: since mobile devices’ display and keypad are limited in term of size

(compared to fixed devices), it is difficult for users to display and browse online

catalogues. Potential assistance to users from intelligent components could be

very appropriate here.

• Transact: since users of mobile devices cannot be constantly connected to the

network, they have to go offline. This means that the transaction process has to

be undertaken without the direct involvement of users. Intelligent components

are needed to follow-up the progress of this process.

• Pay: when payments are due, the exchange of sensitive information has to be

made secure. Specific security protocols and techniques are required and should

deal with the characteristics of wireless networks and mobile devices.

Mobile applications have their own set of obstacles. This definitely translates into

an additional burden on application developers. Developers are put on the front line

for satisfying the promise of businesses and service providers in delivering Internet

content to mobile devices. Varshney, Vetter, and Kalakota report issues that develop-

ers must address to successfully define, design, and implement the necessary hardware

and software infrastructure for m-commerce [6]. The screen size of mobile devices is

very crucial when designing interfaces for customers. Communication channels and

their reliability and efficiency are still a concern (for example, how to recover from a

disconnection). Despite all of these impediments, more advances continue to drive

the wireless field. Indeed, new wireless standards are constantly surfacing, and the

254 December 2003/Vol. 46, No. 12ve COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM

number of devices and programming languages that support mobile applications and

content delivery continues to grow. 3G systems with their data-transmission rate up

to 384Kbps for wide-area coverage and 2Mbps for local-area coverage will provide

high quality streamed Internet content [1]. In addition, since 2001 Java-enabled

I-mode mobile phones are available on the Japanese market; it is becoming possible

to download Java applets from servers to be run on these phones.

What Comes Next?

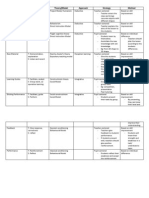

Figure 1 illustrates our perception of the importance of creating an e-commerce appli-

cation that integrates elements from the social context. A different perception is def-

initely needed for m-commerce applications due to the types of devices and

communication channels that are used in such applications. Designing e-commerce

applications that simulate the feeling of being in a real market will definitely give

more confidence to users in carrying out commerce transactions. Similar to 3D video

games, the e-commerce applications will enhance the customers’ shopping experience

by allowing them to walk around the streets of the market, visit shops, read adds, and

chat with vendors. Several research opportunities—for instance, from the intelligent

virtual agents field—are emerging in this context.

The deployment of a virtual e-commerce application suggests a 3D representa-

tion that consists of e-shops, e-floors, e-lanes, and so forth. The representation should

provide shoppers with a new type of virtual experience where shoppers are associated

with components that act on their behalf. Components bind to shoppers with the

help of profiling mechanisms. Furthermore, components need to be embodied with

mechanisms that enable them to sense the market conditions, assess the presence of

other components and their type, and communicate with these components when

needed. Because of the different components that could be involved in a virtual

e-commerce environment, the following contexts and their features are identified in

our work:

Context Features

Shopper-Vendor Sell, bargain, buy

(traditional)

Shopper-Friend Request for advice

Shopper-Shopper Compete/Cooperate/

Be interested in

Vendor-Vendor Compete/Cooperate

(Vendor, Friend)-Shopper Influence to convince

(Shopper, Friend)-Vendor Help to convince

COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM December 2003/Vol. 46, No. 12ve 255

Figure 1. A suggested representation of a virtual e-commerce environment.

• Shopper-Vendor context is not discussed because of its simplicity.

• Shopper-Friend context

– Request for advice feature: the shopper asks her friend for a recommendation

regarding the goods she would like to buy. If the shopper’s friend returns a

positive recommendation, the shopper pursues her purchase. Otherwise, the

shopper may change her intention.When the shopper’s friend does not pro-

vide any recommendation, the final decision of pursuing or stopping the pur-

chase goes back to the shopper.

• Shopper-Shopper context

– Compete feature: two shoppers are in competition for the same goods; the

shopper who offers the highest price will get the goods. However, the final

decision of selling goes back to the vendor who has to take into account his

interests. If the vendor accepts the offer of the first shopper, he has to reject

the offer of the second shopper and vice-versa.

– Cooperate feature: two shoppers are in cooperation and join efforts to get a

better deal from a vendor. For instance, the shoppers decide to introduce a

unique order to ask for a discount and at the same time to share transporta-

tion fees. Acting on behalf of both shoppers, one of them submits a purchase

request to the vendor. The vendor either accepts or rejects the offer.

– Be interested in feature: the shopper is interested in the goods of another shop-

per. Therefore, she decides to get the same goods probably from the same

vendor as the other shopper. If the shopper is aware of the purchase condi-

tions under which the other shopper has obtained the goods, she may request

the same conditions if these conditions meet her requirements.

• Vendor-Vendor context

– Compete feature: two vendors are in competition for the goods to be offered

to the same shopper. For instance, a vendor cuts the prices of his goods. If the

shopper accepts the offer of one of the vendors, she has to reject the offer of

the other vendor and vice-versa.

256 December 2003/Vol. 46, No. 12ve COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM

– Cooperate feature: if a vendor runs out-of-stock for certain goods, he recom-

mends to the shopper another vendor who has the goods in stock.

• (Vendor, Friend)-Shopper context

– Influence to convince feature: the vendor aims at influencing the friend of the

shopper regarding the goods and the selling conditions he is offering. The

objective of the vendor is to influence the shopper’s friend to provide a posi-

tive recommendation to the shopper about the goods of the vendor. This may

aid the shopper in making her purchase decision.

• (Shopper, Friend)-Vendor context

– Help to convince feature: the shopper asks her friend to talk on her behalf to

the vendor regarding the goods she would like to purchase with certain con-

ditions.

Despite the different technologies used for the development of e- and m-commerce

applications, the social context has to be part of these applications. This context is

needed and reflects the interactions occurring between consumers, providers, and some-

times third parties. Working on a workstation or using a mobile device is definitely effi-

cient. However, various aspects that are difficult to assess are missing from the

transaction, such as personalized handling, trust, and face-to-face interactions. How do

you measure a customer’s trust in a provider she has never met? And, how do you ensure

that a customer is satisfied with her order? Online questionnaires and forms can be used,

but will they be able to accurately reflect the user’s behavior and feeling after concluding

a deal? The need for strategies to address the social as well as technology issues is criti-

cal. Can we expect a new generation of commerce systems that will combine both strate-

gies in the same framework? This could pave the way towards the next stage after

m-commerce.

References

1. Elsen, I., Hartung, F., Horn, U., Kampmann, M., and Peters, L. Streaming technology in

3G mobile communication systems. IEEE Computer 34, 9 (Sept. 2001).

2. Kraft, A., Pitsch, S., and Vetter, M. Agent-driven online business in virtual communities.

In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences

(HICSS’32), Hawaii (2000).

3. Liand, T. P., and Huang, J. S. A framework for applying intelligent agents to support elec-

tronic trading. Decision Support Systems 28, 4 (June 2000).

4. Schummer, T. GAMA-Mall: shopping in communities. In Proceedings of the Second

International Workshop on Electronic Commerce (WELCOM’2001), Heidelberg, Germany

(2001).

5. Song, I. Y., and Whang, K. Y. Database design for real-world e-commerce systems. Bulletin

of The IEEE Computer Society Technical Committee on Data Engineering 23, 1 (Mar. 2000).

6. Varshney, U., Vetter, R. J., and Kalakota, R. Mobile commerce: a new frontier. IEEE Com-

puter 10, 33 (Oct. 2000).

COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM December 2003/Vol. 46, No. 12ve 257

You might also like

- E CommerceDocument162 pagesE Commercekaushal_rathoreNo ratings yet

- E-Business Models for TransactionsDocument15 pagesE-Business Models for Transactionsसाई दीपNo ratings yet

- Wheat Ridge-ASDM - Rev 2017 - 201709140930401804 PDFDocument43 pagesWheat Ridge-ASDM - Rev 2017 - 201709140930401804 PDFRavy KimNo ratings yet

- DBE Digital Business Ecosystem OverviewDocument45 pagesDBE Digital Business Ecosystem OverviewhasanNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For Computer ApplicationDocument10 pagesSyllabus For Computer ApplicationJoseph Reyes KingNo ratings yet

- PE7 Running Skills Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesPE7 Running Skills Lesson PlanMetchie Palis89% (9)

- Memorial On Behalf of PetitionerDocument26 pagesMemorial On Behalf of PetitionerSiddhant Mathur50% (4)

- E CommerceDocument62 pagesE CommerceParamita Saha100% (1)

- Impact of Perceived Stress On General Health: A Study On Engineering StudentsDocument17 pagesImpact of Perceived Stress On General Health: A Study On Engineering StudentsGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Study Guide EcommerceDocument4 pagesStudy Guide EcommerceAtieyChentaQasehNo ratings yet

- Rev View Qu Estions::: UreecalldDocument11 pagesRev View Qu Estions::: UreecalldAhmad N. AlawiNo ratings yet

- II M.Com. - 18PCO10 - Dr. M. KalaiselviDocument59 pagesII M.Com. - 18PCO10 - Dr. M. KalaiselviRaj KumarNo ratings yet

- 06 02 MIS Notes - Ecommerce PDFDocument12 pages06 02 MIS Notes - Ecommerce PDFSamarendra ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Intro to Digital Business Chapter 1 SummaryDocument2 pagesIntro to Digital Business Chapter 1 SummaryAziz Putra AkbarNo ratings yet

- E-Business ModelsDocument3 pagesE-Business ModelsshrutiNo ratings yet

- What Are The Cost and Risks For Buyers at Auction and How Have Auction Sites Sought To Reduce These Risks? AnswerDocument8 pagesWhat Are The Cost and Risks For Buyers at Auction and How Have Auction Sites Sought To Reduce These Risks? AnswerJayjay ShalomNo ratings yet

- E BusinessDocument60 pagesE BusinessAkhil GuptaNo ratings yet

- E BusinessDocument17 pagesE BusinessIshaNo ratings yet

- Consumer-to-Business (C2B) MarketingDocument17 pagesConsumer-to-Business (C2B) MarketingJaymart P. PrivadoNo ratings yet

- 1.1 To 1.6Document47 pages1.1 To 1.6Mia KhalifaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of EDocument4 pagesBenefits of EMeenakshiParasharNo ratings yet

- Virtual MarketingDocument131 pagesVirtual MarketingRahul Pratap Singh KauravNo ratings yet

- E-Commerce Lecture NotesDocument46 pagesE-Commerce Lecture NotesLasief DamahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Study GuideDocument25 pagesChapter 1 Study GuideLoretta Lynn AltmayerNo ratings yet

- UNIT 4 HPC 8 Final TermDocument9 pagesUNIT 4 HPC 8 Final TermArjul Pojas Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Ecommerce FinalDocument6 pagesEcommerce FinalAskall ThapaNo ratings yet

- Ommerce AND Ompetition AW Hallenges AND HE AY HeadDocument15 pagesOmmerce AND Ompetition AW Hallenges AND HE AY HeadUtkarsh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- E-commerce Guide: Establishing an Online StoreDocument7 pagesE-commerce Guide: Establishing an Online Storeamid mollaNo ratings yet

- E-Business Models for TransactionsDocument10 pagesE-Business Models for TransactionsBishnu Ram GhimireNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Consumer Protection in CyberspaceDocument8 pagesUnit 4 Consumer Protection in CyberspaceeducationhemaNo ratings yet

- WEEK 14 - E-CommerceDocument25 pagesWEEK 14 - E-Commerceselwyn.magboo789No ratings yet

- E-Commerce Digital Markets and GoodsDocument5 pagesE-Commerce Digital Markets and GoodsJanur Puspa WeningNo ratings yet

- Internet Marketing and E-CommerceDocument4 pagesInternet Marketing and E-CommerceLelouch LamperougeNo ratings yet

- 3.1 Business To Business (B2B)Document23 pages3.1 Business To Business (B2B)assefa horaNo ratings yet

- Ecommerce Applications and Models ExplainedDocument29 pagesEcommerce Applications and Models ExplainedAsmerom MosinehNo ratings yet

- Learning Material for Unit 1Document26 pagesLearning Material for Unit 1shikha22bcom24No ratings yet

- CH-1 EcDocument11 pagesCH-1 Ecfeyisaabera19No ratings yet

- E-Commerce DefinitionDocument4 pagesE-Commerce DefinitionpranllNo ratings yet

- 03 Handout 1Document6 pages03 Handout 1Pauline Sanchez GarabilesNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter1Document16 pages10 Chapter1Shubham TripathiNo ratings yet

- Chapter IiDocument22 pagesChapter IiJane de RamaNo ratings yet

- New Unit 1Document39 pagesNew Unit 1nancy bhatiaNo ratings yet

- E Commerce SDocument20 pagesE Commerce SHarman GillNo ratings yet

- Personalization in E-Commerce ApplicationsDocument38 pagesPersonalization in E-Commerce Applicationsini benNo ratings yet

- To E-Commerce: Chapter # 1Document12 pagesTo E-Commerce: Chapter # 1Muhammad SaqibNo ratings yet

- REPORT ON COMMERCIAL PortalsDocument29 pagesREPORT ON COMMERCIAL PortalsSamiyah SohailNo ratings yet

- INTERNET MARKETING PROJECT PAPER-FinalDocument22 pagesINTERNET MARKETING PROJECT PAPER-FinalJacqueline FarlovNo ratings yet

- Introduction & Business Models: MITC 210 IT Enabled BusinessDocument48 pagesIntroduction & Business Models: MITC 210 IT Enabled BusinessJanus Cesar Ruizan QuilenderinoNo ratings yet

- E-Commerce Handout CHPT 1Document13 pagesE-Commerce Handout CHPT 1Kwao LazarusNo ratings yet

- E CommerceDocument4 pagesE CommerceMarianeNo ratings yet

- E Marketing - BBA 2nd Batch Touhid SirDocument106 pagesE Marketing - BBA 2nd Batch Touhid SirMd. Touhidul IslamNo ratings yet

- E CommerceDocument21 pagesE Commercetannubana810No ratings yet

- 4 E Commerce Business ModelsDocument7 pages4 E Commerce Business ModelsHope WanjeriNo ratings yet

- E Commerce ReviewDocument12 pagesE Commerce ReviewMIRELANo ratings yet

- Business Requirements Specification ContentsDocument6 pagesBusiness Requirements Specification ContentsSHASHIKANTNo ratings yet

- Greg, ($usergroup), 01Document10 pagesGreg, ($usergroup), 01kubakobra2No ratings yet

- Business ModelDocument4 pagesBusiness ModelSarvesh RajNo ratings yet

- E CommerceDocument5 pagesE CommerceAsim KhanNo ratings yet

- OoadDocument10 pagesOoadRaphael MuriithiNo ratings yet

- E-Business Basics - Moore's Law: Error: Reference Source Not FoundDocument10 pagesE-Business Basics - Moore's Law: Error: Reference Source Not Foundimtiaj-shovon-510No ratings yet

- E-Commerce: An Introduction To E-Commerce As A Valid Business Opportunity For The New and Existing BusinessDocument8 pagesE-Commerce: An Introduction To E-Commerce As A Valid Business Opportunity For The New and Existing BusinessRobin SainiNo ratings yet

- Opening Digital Markets (Review and Analysis of Mougayar's Book)From EverandOpening Digital Markets (Review and Analysis of Mougayar's Book)No ratings yet

- Drop Out Rates in Africa and South AsiaDocument37 pagesDrop Out Rates in Africa and South Asiaali abtalNo ratings yet

- Suggested Participants List by CountryDocument5 pagesSuggested Participants List by Countryali abtalNo ratings yet

- University PresidentDocument2 pagesUniversity Presidentali abtalNo ratings yet

- Email List of Over 100 UsersDocument7 pagesEmail List of Over 100 Usersali abtalNo ratings yet

- Bios - Speakers 123Document21 pagesBios - Speakers 123ali abtalNo ratings yet

- ContentServer Mobile MarketingDocument17 pagesContentServer Mobile Marketingali abtalNo ratings yet

- Mobile Marketing: An Approach On Advertising by SmsDocument19 pagesMobile Marketing: An Approach On Advertising by Smsali abtalNo ratings yet

- FUIW University Rankings (QS, THE, SCI, WEBO)Document8 pagesFUIW University Rankings (QS, THE, SCI, WEBO)ali abtalNo ratings yet

- Mobile Marketing: An Approach On Advertising by SmsDocument19 pagesMobile Marketing: An Approach On Advertising by Smsali abtalNo ratings yet

- ContentServer 4 PDFDocument15 pagesContentServer 4 PDFali abtalNo ratings yet

- Module 1 With HighlightDocument10 pagesModule 1 With HighlightDENISE MARQUEZ100% (2)

- Right To Be ForgottenDocument6 pagesRight To Be ForgottenTazeen Ahmed R63No ratings yet

- Advertising Media Choices for BBA CourseDocument20 pagesAdvertising Media Choices for BBA CourseAbhishek DuttaGuptaNo ratings yet

- Save The Environment To Save Life: By: Adithiyan RajanDocument2 pagesSave The Environment To Save Life: By: Adithiyan RajanAlanlovely Arazaampong AmosNo ratings yet

- Job AnalysisDocument27 pagesJob AnalysisNiaz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Introduction to History: Defining the PastDocument26 pagesIntroduction to History: Defining the PastYael EzraNo ratings yet

- 1st QE Grade 11 English 2019-20Document7 pages1st QE Grade 11 English 2019-20Mihatsu TakiNo ratings yet

- Steps P&P Theory/Model Approach Strategy MethodDocument2 pagesSteps P&P Theory/Model Approach Strategy Methodlittle large2No ratings yet

- Evv Timesheet LogDocument1 pageEvv Timesheet Logapi-486793716No ratings yet

- Citizen's Charter for Batac City Government ServicesDocument395 pagesCitizen's Charter for Batac City Government ServicesMark GermanNo ratings yet

- Amar ResumeDocument2 pagesAmar Resumeapi-3700649100% (3)

- Aro Barrackpore Rally Notfn 2021Document15 pagesAro Barrackpore Rally Notfn 2021jayanta naskarNo ratings yet

- Select Best Concept for Product DevelopmentDocument47 pagesSelect Best Concept for Product DevelopmentK ULAGANATHANNo ratings yet

- (SHRM) Corporate CampaignsDocument2 pages(SHRM) Corporate CampaignsNewThorHinoNo ratings yet

- Fiji Clean School ProgramDocument41 pagesFiji Clean School ProgramYesenia Torres Garrido100% (2)

- Dr. Tarek A. Tutunji Engineering Skills, Philadelphia UniversityDocument24 pagesDr. Tarek A. Tutunji Engineering Skills, Philadelphia Universityhamzah dayyatNo ratings yet

- Delhi Urban Art Commission ReviewDocument11 pagesDelhi Urban Art Commission ReviewSmritika BaldawaNo ratings yet

- Liceo de Cagayan University Senior High School DepartmentDocument2 pagesLiceo de Cagayan University Senior High School DepartmentRonald BaaNo ratings yet

- Application Form FOR AffiliationDocument9 pagesApplication Form FOR AffiliationBrilliance International AcademyNo ratings yet

- Industry & Competitive Landscape Analysis: Session 6Document16 pagesIndustry & Competitive Landscape Analysis: Session 6SHIVAM VARSHNEYNo ratings yet

- Main Features of Rural SocietyDocument8 pagesMain Features of Rural SocietyKarina Vangani100% (2)

- Impact of Swami VivekanandaDocument3 pagesImpact of Swami VivekanandaRajesh SarswatNo ratings yet

- Usha Bhatiya: Actress & ModelDocument9 pagesUsha Bhatiya: Actress & ModelDisha SharmaNo ratings yet

- End of Year 1 Higher TestDocument3 pagesEnd of Year 1 Higher TestRoyJJNo ratings yet

- The Packaging Design & Development Process: Project Brief, Specification, & Asset CollectionDocument1 pageThe Packaging Design & Development Process: Project Brief, Specification, & Asset CollectionMehdi SalehiNo ratings yet