Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Religious Responses To Globalisation: Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

Uploaded by

kim cheOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Religious Responses To Globalisation: Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

Uploaded by

kim cheCopyright:

Available Formats

RELIGIOUS RESPONSES

TO GLOBALISATION

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur1

Center of Religious & Cross-Cultural Studies (CRCS) & Indonesian

Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS), Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Abstract

Sociological discussion of globalisation is preoccupied with the political,

economic, and military dimension of it, with little attention to its religious

aspect. This paper attempts to trace the impacts of globalisation on religion

and religious responses, the argument of which derives mainly from the

so-called “Bridge-Building Program” organised by CRCS & ICRS-UGM in

2008. It argues that though they share a common concern, people of different

faiths are at risk of deepening the problems rather than offering solutions in

view of their different responses for which we categorise them into different

but overlapping categories -ideological, ambivalent, integrative, exclusive, and

imitative. It then leads to a more fundamental question of whether interfaith

cooperation is possible given those different and sometime opposing responses.

[Dalam kajian sosiologi, diskusi mengenai globalisasi kerap kali semata-

mata ditinjau dari sisi politik, enonomi dan militer, sementara dimensi agama

sering kali dikesampingkan. Artikel ini membahas dampak globalisasi

terhadap agama dan respon komunitas agama terhadap globalisasi. Data

yang muncul dalam artikel ini diambil dari sebuah workshop berjudul“Bridge-

Building Program.” Melalui artikel ini, saya berpendapat bahwa, meski

1

This article was inspired by consecutive workshops entitled “Bridge-Building

Program” conducted by CRCS & ICRS, in cooperation with Hivos & The Oslo

Coalition, March-July, 2008. This program includes a number of leaders from different

religious groups.

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

komunitas agama-agama memiliki keprihatinan yang sama terhadap dampak

globalisasi, namun respon mereka cenderung mempertajam persoalan yang

diakibatkan globalisasi, ketimbang memberikan solusi. Respon tersebut

dalam dikategorikan –meski tidak kaku- dalam: respon ideologis, ambivalen,

integratif, ekslusif dan imitatif. Selanjutnya, artikel juga mengulas pada

pertanyaan mendasar mengenai apakah kerjasama antar agama mungkin

dilakukan menyimak ragam respon yang saling bertentangan tersebut.]

Keywords: religion, globalisation, responses

A. Introduction

The term globalisation “refers to the expansion and intensification

of social relations and consciousness across world-time and world-

space.”2 It enables people to go beyond their traditional political,

economic, and geographical boundaries and at the same time exposes

them to new social orders that cut across their localities. People of all

regions are by no exception becoming global consumers due to the global

financial market. Technologically sophisticated innovation in information

and transportation has intensified and accelerated social exchanges,

and therefore creating more interdependence between the local and

the global. In addition to its objective material impacts, globalisation

affects also subjective consciousness by giving birth new individual

and collective identities. It generated the so-called ‘global village’ where

people of different identities and geographies easily meet and share

knowledge. To take an example, the program from which this paper is

inspired easily illustrates the case. Muslim participants were sitting next

to their Christian, Buddhist, or Hindus fellows, talking and sharing their

ideas in an air-conditioned conference room equipped with laptops and

projectors. The internet and cellular made it possible for the committee

to contact all participants who are miles away. The recorded materials

made it accessible to “strange people” overseas.

Mass media, such as television and internet, has become the most

powerful medium for globalisation to extend its cultural invasion through

which it inclines the desires and life styles of its consumers toward a

2

Manfred B. Steger, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2009), p. 15.

394 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

particular kind of value, while at the same time it challenges traditional

beliefs and norms. The cultural hegemony of popular culture among

the youth, for instance, has attracted wide and serious attentions from

parents, authorities, or religious leaders. In term of world-economics,

globalisation seems to have created “the winners” and “the losers.” On

one hand, it helped countries such as China, India, Bangladesh and

Vietnam in reducing largely their poverty levels. On the other hand, the

liberalisation of transactions, with transnational cooperation (TNCs) as

the main actors in the global economic world, was behind some financial

crisis in South East Asia in 1997, or currently in the United States, or

economically failed states such as Afghanistan or the Democratic Republic

of Congo. Another salient impact of globalisation is environmental crisis,

which killed and endangered lives of people both in a local or global scale.

The question is then how should religion respond to the above

impacts of globalisation? There is no doubt that all religions share a

common goal to improve the individual and social conditions of human

beings. However, this divine and invaluable goals should now deal with a

greater challenge of the pervasive impacts of globalisation. There is no

doubt that globalisation provides rich opportunities to attain such a goal,

but at the same time, it may increase religious violence and intolerance,

particularly when it means to exclude and neglect differences. This paper

aims to answer such question by building its argument upon the discussion

among the participants during the “Bridge-Building Dialogue” program

B. Globalisation: Definition

Definition of the term “globalisation” is still debatable among

scholars of various disciplines. Many scholars put forward their

definitions with different emphasis on the multifaceted aspects of the

term: economic, political, cultural or ideological. Steger’s illustration of

the ancient Buddhist parable of the blind scholars and their encounter

with the elephant might be helpful to highlight the debate. He said:

Like the blind men in the parable, each globalisation researcher is

partly right by correctly identifying one important dimension of the

phenomenon in question. However, their collective mistake lies in their

dogmatic attempts to reduce such a complex phenomenon as globalisation

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 395

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

to a single domain that corresponds to their own expertise.3

Sociologists may be of the most significant influence in debate on

definitions and theories of globalisation. Marshall McLuhan proposed

the term ‘global village’ in his definition of the term. In his opinion,

globalisation refers to the situation where the speed of communication

has governed a complex range of social interconnections beyond the

boundaries of national, cultural and political spaces. In this globalised

world, people of different locations, through information media,

can experience events simultaneously.4 Anthony Giddens defines the

term as ‘the intensification of worldwide social relations which link

distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by

events occurring many miles away and vice versa’.5 Robertson holds that

globalisation is a concept that “refers both to the compression of the

world and the intensification of consciousness of the world as a whole.”

In its modern sense, globalisation is a set of dimensions rather

than a single process. William A. Stahl, for example, identifies its five

dimensions that include revolution in communication and transportation

technology, politics and military, economics, environment, religion and

cultures.6 The inventions of mass air travel, cable and satellite TV, cellular

telephones, computers, and the Internet in the 1980s and 1990s has

made technologies in communication and transportation become truly

revolutionary. The politic and military dimension of globalisation began

with the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, leading to

what people believe as the U.S. hegemony. The globalisation of economics

began with the rise of transnational corporations and infrastructure such

as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank established by

the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944. The environmental dimension

of globalisation reflects on the fact that population growth and rapid

development of technologies and industries has raised some acute

environmental crisis. The last dimension of globalisation is religion and

culture which Stahl said that though mostly felt and experienced by most

3

Ibid., p.12.

4

Larry Ray, Globalization: Everyday Life (New York: Routledge, 2007), p.1.

5

Anthony Giddens, the Consequences of Modernity (Stanford University Press:

Stanford, CT, 1990), p. 64.

6

William A. Stahl, “Religious Opposition to Globalization,” in Lori Beaman

and Peter Beyer (eds.) Religion, Globalization and Culture (Leiden: Brill, 2007), pp. 336-9.

396 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

people, analysts commonly neglected this last dimension.7 Like Stahl,

Bryan S. Turner also acknowledged lack of attention in sociological

theories toward religion as an inherent part of globalisation, focusing

more on the economic, financial and military aspects of it.8 Accordingly,

sociologists tend to understand ‘religious fundamentalism’ as reassertion

of traditionalism vis-à-vis modernisation that is pivotal characteristics of

the global world.

The case is not much different with respect of how the participants

of the workshop understand globalisation. They understand it as a

multifaceted event in which economic, political and cultural dimensions

are involved. The participants are almost unanimous in seeing that

globalisation has both positive and negative impacts on people’s lives in

general and on religious communities more specifically. Although they

see it as an unavoidable feature of our contemporary life, their responses

are various. It is understandable because the participants have different

emphasis on the phenomena of globalisation, which include different

interpretation of the main actors, of how religion can play its role, and

different concepts of an ideal society according to their religion traditions.

How the participants understand religions can be best categorised

in two different but overlapping approaches. The first views globalisation

as a process of integration and interaction in which globalisation means

integration of time and space which results in the increasingly reduced

importance of the ‘imaginary boundaries’ of state territories, leading

to the so-called ‘global village.’ Economic, socio-politic and cultural

processes are among the main factors underlying this process of time

and space integration. As time and space are reduced and integrated,

national, religious and cultural exchange among people are intensified

and accelerated as well, making them interdependent to each other.

The second approach regards globalisation with emphasis on certain

ideologies like capitalism (“McDonaldization” or “Americanisation”). The

group who hold this approach argued that globalisation is not, and it is

not all about, a mere process of turning the world into a global village

through technological discoveries. Rather, it is imperialism of “Capitalism

of the West” with its all faces such as colonialisation in the 19th and 20nd

7

Ray, Globalization, pp. 345-48.

8

Ibid., p. 154

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 397

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

centuries and its new form of modernisation and development after

the end of the Second World War.9 In short, whatever the definition of

globalisation is, it is closely related to certain values we introduced into

our definition of the term, which in turn will determine our responses

to its effects. That globalisation has both negative and positive affects is

not questionable. The question is how we respond to them, particularly

to the negative ones.

C. Religion and Globalisation: Some Impacts

It is commonly agreed that all great religions emerged in three

centers of civilisation in the ancient world, i.e. China, India and the

Middle East. All these religions spread over the continents and meet each

other in other areas. As a result, we may see different sacred sites in one

city where a mosque is next to a church, a temple, or a synagogue. The

travel of religions and its embrace by more people led to what Lyotard

called it as “loss of centre” in which we see a worldwide diffusion of

religions and diaspora among their adherents and their sacred centers

out of its first homeland.10 Similarly, Paul F. Knitter, drawing on David

Loy,11 sees the phenomena of free market fundamentalism as the new

world religion in which a religion, like a free market, is becoming new,

universal, absolute, and exclusive all over the world.

In the modern period, world religious systems have a huge

opportunity to transform themselves at a global scale because of an

increasingly developed system of communication and transportation.

Abrahamic religions (i.e. Judaism, Catholicism, and Islam) work on a

largely globalised linkage and articulate themselves globally through

trading and educational systems and networks. For example, relationship

9

Nopriadi, “A Better World is a Must,” unpublished paper presented at the

workshop “Globalization, Media, and Education of the Youth, CRCS & ICRS, March

8-9, 2008, pp. 3-4.

10

John L. Esposito, Fasching Darrel, Lewis Todd, Religion and Globalization: World

Religions in Historical Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 5

11

David R. Loy, ‘The Religion of the Market’ in Journal of the American Academy of

Religion, vol. 65, no. 2, Summer 1997, pp. 275-290; see also Paul Knitter, ‘Globalization

and the Religions: Friends or Foes?’ unpublished paper presented on May 24, 2006

at a Research Seminar on Globalization and Religion: Friends or Foes?, Centre for

Religious and Cross-Cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

398 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

between Islam in Malay-Indonesia and the Middle East has been

established since the seventeenth century. Indonesian Muslims are

inseparable from those in the Middle East, and this network plays a crucial

role in transforming the impulses of Islamic reformism in Indonesian

Archipelago.12

Globalism does not only affect the spread of religions, but also

the diverse responses of the indigenous people toward those global

Abrahamic religions. In every civilisation, confrontation, tension, and

readjustment have always accompanied religious encounters. In Southeast

Asia, encounters between Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity

took place in every state, such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and

the Philippines. Many Arab traders who are mostly from Hadramaut,

Buddhist monks who are mostly from Ceylon, and Chinese Con Fu

Cian, come to the Archipelago for many centuries and represent a major

source of “global” religions in Indonesia. Many of them serve as religious

teachers as well as traders.

It seemed that religion through globalisation has moved to fill the

economic gap between developed and developing countries. Many global

religious movements like those in Islam, Western Christianity, Judaism,

Buddhism and Hinduism were established across the boundaries of

continents and nation-states. American Judaism that supports the Israeli

State or the Middle Eastern states that stand for Malay Muslims of the

Southern Thailand and the Southern Philippine might be good examples.

Some scholars on religion, like George Weigel, Gilles Kepel and Peter

L Berger,13 said that global religions have raised a sense of “the un-

secularization of the world” or “the revival of global religion” in which

a particular religion transcends its national boundaries and economical

gaps. Globalism has indeed generated a stronger feeling of religiosity than

nation-states. For example, a person may be a half-French, a half-Arab,

12

See further Azyumardi Azra, the Origins of Islamic Reformism in Southeast Asia:

Networks of Malay-Indonesian and Middle Eastern “Ulama” in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth

Centuries (University of Hawaii, 2004).

13

See further these arguments in Gilles Kepel, the Revenge of God: The Resurgence

of Islam, Christianity and Judaism in the Modern World (Polity Press Publisher, 1993); Peter

L Berger, “Desecularization of the World, a Global Perspective” in Peter L Berger

(ed.), the Secularization of the World, Resurgent World and World Politics (Ethic and Public

Policy Centre, 1999).

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 399

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

while simultaneously belonging to dual citizenships. On the contrary, it

is almost impossible to be a half-Catholic and a half-Muslim.

Because of globalisation, the world is becoming smaller, inevitably

leading to increasingly intensified interactions among peoples of different

religions and cultures. This interaction, to some extent, enhances the

civilisation-consciousness of the people, which in turn revitalises their

differences and animosities that are deeply rooted in their thoughts and

histories. Huntington14 describes that the raise of cultural identity has

worsened the global paradox, which in turn leads to a clash of world

civilisation. The numbers of civilisations, which consist of states,

ethnicity, geographical proximity, linguistic similarity, social groups

and predominantly religions, seemed to split exclusively into major

civilisations. Western civilisation, which is centered in the Northern

America, West Europe, and the former of Soviet Union states, are in

fight with the Eastern Civilisation represented by the Buddhist culture in

Thailand, Korea, Singapore, and the Hindus culture in India, and Japanese

civilisations. This clash of civilisation becomes more complicated when

the Muslim worlds represented by the Greater Middle East states such

as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, and the North African states such as Egypt

as well as the Muslim states in South Asia and Southeast Asia, including

Indonesia, are also involved.

The theory of clash civilisation suggests that the fundamental

cause of conflict nowadays is neither ideological nor economic, rather

the great polarisation among the cultural humankind and its religions.

Since the post-Cold War, the latter is embodied in the struggle among

different cultural and religious identities, i.e. the Western civilisation vis-

à-vis Islamic civilisation and the “rest” of civilisation. Reactions toward

globalisation has strengthened those identities, the result of which is that

people are defined mainly by their common objective elements, such as

language, history, religion, customs, institutions, and their subjective self-

identifications. The fact that in the post-Cold War, the conflict between

classes and ideologies of communism, socialism and nationalism is not

debatable, during which one is not asked a question, “what side you are

on?” rather “what are you?” (That is, “what is your religion?” or “what is

See further Samuel Huntington, the Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of

14

World Order (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996).

400 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

your ethnicity,” and so on). This phenomenon shows us that nation-states

are not the only principal actors in the global affairs, but it also includes

a sense of belongingness to ethnic and religious identities.

The global paradox of the clash of civilisation is not only true, but

it also serves as a basic problem. The reason is that people is differentiated

from each other by their historical experiences, languages, traditions, and,

most importantly their religions. In addition, among those civilisations

there are different views on relations between God and man, the holy

texts and religious values, the individual and the group, the parents and

the children, the husband and the wife, as well as those of the relative

importance of rights and responsibilities. These differences are far

more fundamental than those in political ideologies and regimes. For

instance, some Indonesian people suggest that globalisation and religion

are incompatible to each other. For this group, globalisation is rooted

in modernity and neo-liberalism that follow from the greedy-Western

philosophy, immorality, individualism and capitalist domination.

In addition to clash and confrontation, religious encounters are

also accompanied with mystical interactions among different religions,

from which a newly common culture and cosmology is born. The

interaction between Hinduism and Christianity in the nineteenth century

of Java resulted, for example, in the Javanese images of Jesus Christ

in the Catholic Church or candi (temple) of Ganjuran.15 Indonesian

religions appeared to be very different from those in other places. Islam

in Indonesia is the most striking example. Islam in Indonesia is different

from one in Arabian Peninsula because of strong influence from Indian

religions (i.e. Hinduism and Buddhism) in the Archipelago, not to

mention indigenous religions that are full of venerations, spirits and cults.

Muslims of regionally and ethnically different origins first brought Islam

to Indonesia, particularly from the entire coastline of South Arabia to

Southern India and China.16 As a result, Islam in Indonesia was gradually

incorporated into local practices. The encounters between global and local

religions in Indonesia resulted also in the clash between adat (custom) vis-

à-vis agama (religion), in which the former refers to locality in response to

Merle Ricklefs, Polarizing Javanese Society, Islamic and Other Visions (c 1830-1930)

15

(Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007), pp. 122-3.

16

Azyumardi Azra, the Origins of Islamic Reformism.

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 401

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

the global Islam. In modern Indonesia, some Muslims perceive that adat is

in conflict with the notion of shari>‘a. As Muslims rapidly and increasingly

diffuse from Arabia in the 1930s up to the current decentralisation era,

local customs has repeatedly come under threats and attacks by the so-

called reformists and “scripturalists.”

In Indonesia, Islam becomes one of the most controversial

religions over a decade because of the rapid growth of fundamentalist

groups. Roughly, Islamic fundamentalism advocates totalism and

rejects privatisation of religion. Islam is the religion of the majority in

Indonesia, reaching over 90% of adherents out of the total number of

Indonesian citizen. Because the concept of umma (Muslim communities)

is transnational, the umma believe that they are unified regardless of the

boundaries of nation-states. The rapid migration of Muslims lead to

the vast number of Muslims in non-Arab worlds, like India, Pakistan,

Bangladesh, Indonesia, and even in the West Europe. This vast diffusion

of Muslims over the world represents the impact of the globalisation on

religion. However, the problems emerge as some Muslims interpret that

being a Muslim is not a matter of personal faith, rather it is also political,

legalistic, and economic, due to which Islamic empires and states began

to come into existence.17

Globalisation invites criticisms from many scholars, most of which

is laid upon its paradox. Global modernity is then questionable because

there is a belief that it produces inadequate developments, inequalities,

too rapid urbanisation, leaves the peasantry in a precarious economic

situation, and erodes and alienates people from their local cultures and

religions. Some argued that solutions to modernity and globalisation are

to be found in fundamentalist traditionalism that is in opposition with

the global market systems and their laws. Some rely on nationalism as

opposed to the egalitarian abstraction of global citizenship. Because

of globalisation, they identify humanity with the market per se, the

competitors, the consumers, etc. They also perceive human beings as

homo-economicus. The public sphere and discourse are systematically de-

theologised. Theology, God and holy houses are replaced with pseudo-

17

Karen Armstrong, Islam: A Short History (Modern Library, 2002), p115; Amin

Mudzakkir, Antara Iman dan Kewarganegaraan: Pergulatan Identitas Muslim Eropa,

Jurnal Kajian Wilayah Eropa-UI, Vol. V., No. 1, 2009, pp. 46-61.

402 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

religions in which transnational corporations serve as the high priests

of the global temple.

Nevertheless, the project of globalism is now dealing with three

challenges: (1) the emergence of a global Islamic political system; (2)

the cultural reaction of Islamic fundamentalism against Westernisation,

democracy and consumerism; and (3) the conflicting ideas between

pluralism and fundamentalist commitments in respect to the different

and sometimes conflicting values, lifestyle and beliefs.18 In Indonesia,

the problems in respect with religiosity is, to mention some, whether

Islam is to be integrated into the state of law or to be restricted to a

personal life. As modernity came, religion began to be seen more as a

matter of personal opinion rather than a subjective knowledge, and it,

therefore, becomes problematic when some Muslim groups insist on the

integration of Islamic laws and rules into modern bureaucracies. A debate

on the Jakarta Charter in 1945, that is whether it is necessary to include

Islamic law or not as the principle of Indonesian state, illustrates as a

good example.19 Similarly, some Christians in Indonesia inclined also to

reject modernity by referring to the historical past as the ideal future and

insisted that science and knowledge will bring a more glorious future. In

short, the believers are now struggling with the question of relationship

between their religious traditions and modernity with all its developments

and problems in science, technology, transportation, nuclear energy,

chemical warfare, and other fields. The question includes how religions

should face and respond to a modern and secular world in which global

tensions are intensified also by a sense of suspicious feelings between

Muslims and Christians, for example.

Hatred between Muslims and Christians took place since the

colonial periods during which the former considered the latter as a

part of colonisation. In Indonesia, we see that these global colonial

encounters raised confrontation, admiration and imitation that influence

Muslim communities. Meanwhile, Indonesian Muslims encounter also

other alternative ideologies such as nationalism, capitalism and social

communism, which are followed by the polarisation and the raise of

18

Brian Turner, Orientalism, Modernism, and Globalization (New York: Routledge,

1994), p. 77.

19

Jan S. Aritonang, Sejarah Perjumpaan Kristen dan Islam di Indonesia, (Jakarta: BPK

Gunung Mulia, 2004), p. 371.

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 403

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

political streams among Indonesians in the twentieth century. Geertz,

for instance, elucidates this polarisation among Javanese people into

trichotomy, i.e. santri (pious Muslim), abangan (Javanese mystics) and

priyayi (Javanese elites).20 Another example is that under the regime of

President Soekarno, Indonesia was in resistance toward the domination

of the West, while at the same time it systematically embraced capitalist

and global economic systems during the New Order Regime led by

President Suharto.

During the 1970s-1980s, global networks linked Islamic

movements and Islamic fundamentalism in Indonesia to the spirit of

Islamic resurgence. Islamic activists and the idea of revivalism were

institutionalised in many contexts. During the New Order period, for

example, we see the development of Islamic institutions, such as those

exemplified by the growth of Islamic schools, clinics, hospitals, legal aids,

disaster relief, youth centers, banks and Islamic political parties. Islam at

the local level changes because of global influences from the emergence

of Islamic revival movements in the late 1970’s. The changing patterns of

Muslim separatism in the Philippines, Thailand, Aceh, and the collapse

of Communism as well as the issue of terrorism, have affects also on

the Muslim communities at the local level.

D. Religion & Globalisation: Model of Responses

It can be argued that religion would not be able to contribute

positively to the social life unless its adherents transform and implement

their religious values properly. It implies the necessity of reinterpreting

religious themes when facing the current problems. Although religious

symbols occupy a very high portion, yet the adherents’ behaviors do

not represent their religious values. The challenge is how, according to

Evi, people should read their religious symbols in a more substantial,

rather than merely a symbolic, manner. In line with this idea, Bagir, an

Indonesian scholar, pointed out that the negative effects of globalisation

may be resisted by making use of religious spirits in all fields.21 These were

example of responses from some of participants during the “Bridge-

Clifford Geertz, The Religion of Java, (New York: The Free Press, 1960).

20

CRCS & ICRS team, Workshop proceedings: Bridge-Building Dialogue. Unpublished,

21

Yogyakarta, 2008, p. 5.

404 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

Building Program.”

One response takes a clear-cut, ideological position against

globalisation, referring to religion as an alternative and a cure. It argues

that religion itself has a power to deal and overcome problems raised by

globalisation. Nopri, a prominent leader of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia/

HTI, for example, pointed out that Islam offers solutions to solve the

problems of globalisation. This is so because, he said, Islam is not just

a religion that only deals with worship toward the Creator, but it serves

also as an ideology with detailed concepts of governing public affairs.

Islam, he continued, provides a unique concept of economic, political,

governmental, social, cultural, legal, educational systems. Therefore,

Muslim, he insisted, should be more loudly and more optimistic about

voicing the need to change the current world system. He also argues that

Islam has no problem with globalisation as long as the term is understood

as a process of human integration. Nopri suggested that Muslims must

take advantage of technology, information, etc. HTI, he said, is a political

party whose goal is to replace capitalism with Islamic civilisation. For him,

globalisation is a comprehensive ideology of capitalism and covers all

aspects of human life. Globalisation is a capitalist civilisation that attacks

and hits all over the world, particularly the Muslim world. It attempts to

erode Islamic identities and make Muslims identical with the West. The

ultimate goal of globalisation, he said further, is human exploitation

unhindered by the state, culture, rules, and of human values.22

Globalisation has an extraordinary negative impact on the world.

HTI looks at the need for a better world, and it tries to disseminate that

Islam, instead of capitalism, is a better alternative to the new world.23

Here, we can see that an Islamic organisation such as HTI takes a firm

stand against globalisation in which it sees globalisation as a dangerous

phenomenon that must be responded intelligently. Therefore, people

must be fully aware in facing this phenomenon. Proactive attitudes must

be developed in response to the universalisation of the capitalist ideology

that is only exploiting the world, especially the Islamic one.

Some also argued that the impact of globalisation is ambivalent.

22

Nopriadi, “Memahami Globalisasi: Proses Integrasi Umat Manusia dalam

Arus Kapitalisme Global,” [http://www.khilafah1924.org]. This paper is also presented

at one of the three workshops, March 8-9, 2008.

23

Nopriadi, “A Better World,” pp. 7-8.

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 405

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

Globalisation with its highly super-fast trend has negated humanitarian

processes, leading to the alienated people. “The global trend established

a tradition that is simple, fast and tends to see the core of the process at

its physical and materialistic model, said Rahman, a Muslim participant.

Other Muslim participant, for example, perceives that the positive impact

of globalisation is very little, while the negative impact is more pertinent as

the result of our own mistakes, especially those in the field of education.

It is argued that “educational system in Indonesia is on the wrong track

because it is only aimed at the developments of the brain and physics

with a little attention on morality,” said Thoha Abdurrahman.24 The

reason why many people see globalisation in a negative way is due to its

ignorance on human morality and spirituality.

The above ambivalent responses to globalisation strengthen

Berger’s pessimistic opinion on Islam in dealing with globalisation. Islam

has unfavorable aspects to the development of a global civil society, i.e.

its understanding and interpreting of law, jiha>d and the role of women

that have been traditionally defined as having inferior status. The notion

of shari>‘ah, for example, is inherent in the relation between religion and

state, which hinders the modern economic development and the global

civil society institutions.25 The obstruction of economical and politic

developments under globalisation is due to religious polarisation as

well. Interpretation on histories, texts and political interests stimulate

hostility and separation within one religion. It takes place globally, either

among Catholics in Northern Ireland, Buddhism in Sri Lanka, or Islam

in Southeast.

Some participants attempt to integrate between locality, nationality

and globality. It does not mean that this group fully accepts globalisation

without any notice; rather, they combine it with their local culture in a

critical manner. In an integrative way, religious communities may “accept”

globalisation as part of the process of their lives as outlined by God, in

which human beings, as a caliphate in the world is assigned to “escort”

globalisation. Those who belong to this idea argued that all of humankind

has in fact common good interests. Human beings can learn from each

24

Workshop proceedings, p. 10.

25

Peter L. Berger, “Religion in Global Civil Society” in Mark Juergensmeyer

(ed.), Religion in Global Civil Society (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 18.

406 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

other so that they can work together and eventually live side by side as

one single family. The integrative sides of globalisation in Indonesia take

the form of socio-political changes that include openness. Indonesian

people are more concerned with at least four global issues, including

democracy, human rights and environmental sustainability as well as the

freedom of the press as an integral part of social communication systems.

There are also participants who hold an exclusive response in which

they reject globalisation as it threatens morality, spirituality and religion.

Globalisation does not only create an increasingly consumerist, apathetic,

individualistic society but also it erodes and alienates people from their

local cultures and religions. They refuse globalisation by excluding

themselves from this global phenomena or even strengthening their own

identities. In fact, this tendency is found in all religious communities,

including Islam, Christianity, Hinduism and other fundamentalists in

several places. It is become undeniable fact. In this sense, globalisation

appeared as a paradox in which it triggers uniformity and homogeneity

in terms of communication systems and lifestyles and at the same time, it

strengthens cultural heterogeneity in the form of primordialism, cultural

localism and religious fundamentalism. This negative response follows

from the belief that religion is only about spiritual, nothing to do with

social responsibility. It neglects the fact that religion can give a positive

response when its believers are willing to cooperate, develop ethics in

order to provide a positive contribution to this nation, as to work together

to tackle the problems of poverty. They blame that globalisation along

with its tools such as the internet, pluralism projects, secularism and

liberalism is a conspiracy theory of Judaism to destroy Islamic world.

Jewish people become a scapegoat since they proved to be able to produce

“superhuman,” scientists, capitalists; those people become puppet masters

(dalang), who are working with America and Israel to control the world.26

26

For example, Dewan Dakwah under the leadership of Muhammad Natsir

is in polemic against Christianity and Judaism, and it believes that globalisation put

Islam under the new threats of a new Christian Crusade and international Jewish

conspiracies. This hatred pursued Committee for Solidarity with the World of Islam

(KISDI) during the 1990s, which then actively pressured the government to protect

Muslims in Indonesia from any Western influence; see Martin van Bruinessen, “Global

and local in Indonesian Islam,” Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 37, no.2 (1999), pp. 46-63.

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 407

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

E. Conclusion

Looking at different responses above, we may also conclude that

there are opportunities and constraints for an interfaith cooperation to

take place in response on globalisation. Seen as an integration of time and

space, globalisation is an avoidable phenomenon to which all religions

should deal with. In the context of pluralistic Indonesian societies, the

bad impacts of globalisation in the form of, to mention some, poverty,

morality, and ecological problems, are issues to which all religions in

the country have to face. In this sense, interfaith cooperation become

more feasible when all different religions regard those real problems

as their common concerns, regardless of their theological differences.

Therefore, it seems that an integrative response as explained earlier is

the best for the realisation of interfaith cooperation since it implies that

globalisation generates a common concern on the destructive impacts

of globalisation on religions.

Religion is required to collect, move, and empower all moving in

unison to realise the ecological measures as a form of faith. Religion

makes his followers for daring to talk about ecological issues, so that

humans and all creatures are protected from natural disasters, religion can

also urged his followers to seek an agreement to end the destruction of

God’s creation. Religions are supposed to encourage their followers to

conduct interfaith cooperation in order to find alternatives that can bring

life to each other and make this world better. Religion should become

a community of hope for those who need assistance from the threat of

the hope of life in the middle of the absence of climate change in the

current fierce.

408 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

Religious Responses to Globalisation

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aritonang, Jan, S, Sejarah Perjumpaan Kristen dan Islam di Indonesia, Jakarta:

BPK Gunung Mulia, 2004.

Azra, Azyumardi, The Origins of Islamic Reformism in Southeast Asia: Networks

of Malay-Indonesian and Middle Eastern “Ulama” in the Seventeenth and

Eigteenth Centuries, University of Hawai’i, 2004.

Berger, Peter L, “Religion in Global Civil Society” in Mark Juergensmeyer

(ed.), Religion in Global Civil Society, Oxford University Press, 2005.

Beyer, Peter. Systemic Religion in Global Society. Inside The Transnational Studies

Reader: Intersections and Innovations. Sanjev Khagram and Peggy Levitt

(eds.), New York and London: Routledge, 2008.

Bruinessen, Martin van, “Global and local in Indonesian Islam,” Southeast

Asian Studies (Kyoto) vol. 37, no.2, 1999.

Clifford Geertz, The religion of Java. New York: The Free Press, 1960.

CRCS-ICRS, Workshop Proceedings, Bridge Building Dialogue, Globalization:

Challenge & Opportunities for Religion, Yogyakarta, 2008.

Esposito, John L; Fasching Darrell; Lewis Todd., Religion and Globalization.

World Religions in Historical Perspective, Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2008.

Huntington, Samuel, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World

Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Knitter, Paul, ”Globalization and the Religions: Friends or Foes?”

unpublished paper presented on May 24, 2006 at a Research

Seminar on Globalization and Religion: Friends or Foes? at Centre

for Religious and Cross-Cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University,

Yogyakarta.

Loy, David R, ‘The Religion of the Market’ in Journal of the American

Academy of Religion, vol. 65, no. 2, Summer 1997.

Mudzakkir, Amin, “Antara Iman dan Kewarganegaraan: Pergulatan

Identitas Muslim Eropa,” Jurnal Kajian Wilayah Eropa-UI, Vol. V.,

No. 1, 2009.

Nopriadi, “Globalization, Media and education of young people”. A

paper presented at the workshop, 8-9 March 2008 by the Center for

Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H 409

Hatib A. Kadir & Maufur

Religious and Cross - Cultural Studies (CRCS) and the Indonesian

Consortium for Religious Studies (ICRS-Yogya).

----, “Memahami Globalisasi: Proses Integrasi Umat Manusia dalam Arus

Kapitalisme Global,” [http://www.khilafah1924.org] . This paper

is also presented at one of the three workshops, March 8-9, 2008.

Ray, Larry, Globalization: Everyday Life, New York: Routledge, 2007.

Ricklef, Merle. Polarizing Javanese Society, Islamic and Other Visions (c 1830-

1930), Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007.

Robertson, Roland, Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture, London:

Sage, 1992.

Steger, Manfred B, Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2009.

410 Al-Ja>mi‘ah, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011 M/1432 H

You might also like

- Contemporary WorldDocument39 pagesContemporary WorldEmmanuel Bo100% (9)

- The Political Economy of NGOs: State Formation in Sri Lanka and BangladeshFrom EverandThe Political Economy of NGOs: State Formation in Sri Lanka and BangladeshNo ratings yet

- Windows Server 2019 Administration CourseDocument590 pagesWindows Server 2019 Administration CourseTrần Trọng Nhân100% (2)

- The Management Reporting SystemDocument33 pagesThe Management Reporting Systemkim che100% (1)

- Berlitz Examination GuideDocument23 pagesBerlitz Examination Guidekim che50% (2)

- #Test Bank - Law 2-DiazDocument35 pages#Test Bank - Law 2-DiazKryscel Manansala81% (59)

- The Contemporary WorldDocument39 pagesThe Contemporary WorldIan Cunanan100% (3)

- RA 7277 - Magna Carta of Disabled PersonsDocument18 pagesRA 7277 - Magna Carta of Disabled PersonsVanny Joyce Baluyut100% (3)

- Barangay Micro Business Enterprise (Bmbe) Act: 13284-TOPIC 3Document16 pagesBarangay Micro Business Enterprise (Bmbe) Act: 13284-TOPIC 3kim cheNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-The Study of GlobalizationDocument21 pagesChapter 1-The Study of GlobalizationSohkee Vince GamazonNo ratings yet

- Globalisation EssayDocument27 pagesGlobalisation Essaycarmenc92No ratings yet

- Article 1767-1768Document16 pagesArticle 1767-1768kim cheNo ratings yet

- Understanding Globalization Through Its DefinitionsDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Globalization Through Its Definitionsshaina juatonNo ratings yet

- Heavenly Nails Business Plan: Heaven SmithDocument13 pagesHeavenly Nails Business Plan: Heaven Smithapi-285956102No ratings yet

- Special Economic ZoneDocument19 pagesSpecial Economic Zonekim cheNo ratings yet

- Philippine Constitution Association vs Salvador Enriquez ruling on veto power, pork barrelDocument1 pagePhilippine Constitution Association vs Salvador Enriquez ruling on veto power, pork barrellckdscl100% (1)

- Providing Safe Water Purification Units to Schools and Communities in Dar es SalaamDocument19 pagesProviding Safe Water Purification Units to Schools and Communities in Dar es SalaamJerryemCSM100% (1)

- LECTURE NOTES - PAS 21 and PAS 29Document4 pagesLECTURE NOTES - PAS 21 and PAS 29kim cheNo ratings yet

- Article 1774-1783Document35 pagesArticle 1774-1783kim che50% (2)

- Bhumi Soni A-24 Law & JusticeDocument29 pagesBhumi Soni A-24 Law & JusticePrashant PatilNo ratings yet

- A Chart On The Covenant Between God and Adam KnownDocument1 pageA Chart On The Covenant Between God and Adam KnownMiguel DavillaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Study of Globalization: Ge103 - The Contemporary WorldDocument4 pagesIntroduction To The Study of Globalization: Ge103 - The Contemporary Worldmaelyn calindongNo ratings yet

- Case Study Chapter 4 ECON 225Document9 pagesCase Study Chapter 4 ECON 225kim cheNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-Financial MarketsDocument18 pagesChapter 1-Financial Marketskim cheNo ratings yet

- WEEK4LESSONTCWDocument22 pagesWEEK4LESSONTCWEmily Despabiladeras DulpinaNo ratings yet

- Globalization, Poverty, and International DevelopmentFrom EverandGlobalization, Poverty, and International DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary World (GE 3) : A.Y. 2020-2021, First SemesterDocument21 pagesThe Contemporary World (GE 3) : A.Y. 2020-2021, First SemesterJeric Sebastian Ganara100% (1)

- 3rd Week Module in Contemporary World - BaylonDocument12 pages3rd Week Module in Contemporary World - Baylonqueenie belonioNo ratings yet

- Globalisasi Budaya Dan Tantangan Untuk Teori Komunikasi TradisionalDocument18 pagesGlobalisasi Budaya Dan Tantangan Untuk Teori Komunikasi Tradisionalrahmad08No ratings yet

- 21.12.globalization and Internationalization in Higher Educa-30-63Document34 pages21.12.globalization and Internationalization in Higher Educa-30-63ioselianikitiNo ratings yet

- Lauren Movius - Cultural Globalisation and Challenges To Traditional Communication TheoriesDocument13 pagesLauren Movius - Cultural Globalisation and Challenges To Traditional Communication TheoriesCristina GanymedeNo ratings yet

- Unit 4: A World of Ideas: Learning CompassDocument3 pagesUnit 4: A World of Ideas: Learning CompassRica Mae Lepiten MendiolaNo ratings yet

- CW - Module 2Document15 pagesCW - Module 2Dahlia GalimbaNo ratings yet

- Christianity and Globalisation, An Impact ReviewDocument18 pagesChristianity and Globalisation, An Impact ReviewPastor(Dr) Dele Alaba IlesanmiNo ratings yet

- GE6 Module 3Document9 pagesGE6 Module 3Crash OverrideNo ratings yet

- Defining GlobalizationDocument5 pagesDefining GlobalizationCagadas, Christine100% (1)

- Sedigheh Babran - Media, Globalization of Culture, and Identity Crisis in Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesSedigheh Babran - Media, Globalization of Culture, and Identity Crisis in Developing CountriesCristina GanymedeNo ratings yet

- InTech-Globalization and Culture The Three H ScenariosDocument18 pagesInTech-Globalization and Culture The Three H ScenariosSherren Marie NalaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalization On Religion: (University Name)Document15 pagesImpact of Globalization On Religion: (University Name)Obaida ZoghbiNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Culture - The Three H ScenariosDocument19 pagesGlobalization and Culture - The Three H ScenariosWilly WonkaNo ratings yet

- 2 E Globalization and PakistanDocument9 pages2 E Globalization and PakistanNabeelapakNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTION TO GLOBALIZATION ModuleDocument8 pagesINTRODUCTION TO GLOBALIZATION Modulevalleriejoyescolano2No ratings yet

- Globalization: An Agenda: January 2013Document23 pagesGlobalization: An Agenda: January 2013Jean EspantoNo ratings yet

- Globalization Defined: Understanding Competing ConceptionsDocument17 pagesGlobalization Defined: Understanding Competing ConceptionsRegine MabagNo ratings yet

- Eiabc: Department of Anthropology AssignmentDocument10 pagesEiabc: Department of Anthropology AssignmentGirum TesfayeNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary WorldDocument32 pagesThe Contemporary WorldAxel Ngan50% (2)

- Dominican College of Tarlac module explores globalization theoriesDocument21 pagesDominican College of Tarlac module explores globalization theoriesCNo ratings yet

- The Role of Globalization and Integration in InterDocument17 pagesThe Role of Globalization and Integration in Interlatharamreddygari2112No ratings yet

- 42rkjz88v Lit 1 Contemp - World 1Document97 pages42rkjz88v Lit 1 Contemp - World 1Jesica BalanNo ratings yet

- GE3 Forum#1Document4 pagesGE3 Forum#1Lalaine EspinaNo ratings yet

- Globalization in IndiaDocument12 pagesGlobalization in Indiawarezisgr8No ratings yet

- Ge 7 - Chapter 1 (Outline Summary)Document5 pagesGe 7 - Chapter 1 (Outline Summary)Princess Jean MagdangalNo ratings yet

- Globalization People, PerspectivesDocument5 pagesGlobalization People, PerspectivesBack Claro TXNo ratings yet

- What Is The Driving Force of Globalization?Document11 pagesWhat Is The Driving Force of Globalization?Shamim HosenNo ratings yet

- vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.documentrendition1 (1)Document9 pagesvnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.documentrendition1 (1)sachied1023No ratings yet

- Globalization Learning Outcomes DefinitionsDocument2 pagesGlobalization Learning Outcomes Definitionskassel PlacienteNo ratings yet

- International Studies-Final Exam-PinkihanDocument17 pagesInternational Studies-Final Exam-PinkihanBielan Fabian GrayNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary World (Compact Version)Document39 pagesThe Contemporary World (Compact Version)TANAWAN, REA MAE SAPICONo ratings yet

- Religion and Globalization New Possibilities Furthering ChallengesDocument11 pagesReligion and Globalization New Possibilities Furthering ChallengesFe CanoyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To GlobalizationDocument5 pagesIntroduction To GlobalizationCiaran AspenNo ratings yet

- After centuries of technological progress and advances in international cooperation, the world is more connected than everDocument13 pagesAfter centuries of technological progress and advances in international cooperation, the world is more connected than everPre Loved OlshoppeNo ratings yet

- Religion and Globalization New Possibilities Furthering ChallengesDocument11 pagesReligion and Globalization New Possibilities Furthering ChallengesUly SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Globalization: Impact On Society and CultureDocument21 pagesGlobalization: Impact On Society and CulturePre Loved OlshoppeNo ratings yet

- Globalization's Impact on EducationDocument46 pagesGlobalization's Impact on EducationJohn TongNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Globalization TheoriesDocument13 pagesChapter 1 - Globalization TheoriesJohn Paul PeressNo ratings yet

- Prepared By: John Joshua GepanaDocument24 pagesPrepared By: John Joshua GepanaJohn Joshua GepanaNo ratings yet

- PS4882 WK1 Mauro GuillenDocument27 pagesPS4882 WK1 Mauro GuillenedmundNo ratings yet

- Gec-Cw Chapter 1Document38 pagesGec-Cw Chapter 1shinamaevNo ratings yet

- Reconciliation Through Communication in Intercultural EncountersDocument11 pagesReconciliation Through Communication in Intercultural EncountersΔημήτρης ΑγουρίδαςNo ratings yet

- Module 1 13 TCWDocument33 pagesModule 1 13 TCWCristobal JoverNo ratings yet

- Written ReportDocument2 pagesWritten ReportMaxGabilanNo ratings yet

- Week3lessontcw PDFDocument19 pagesWeek3lessontcw PDFEmily Despabiladeras DulpinaNo ratings yet

- Remapping Knowledge: Intercultural Studies for a Global AgeFrom EverandRemapping Knowledge: Intercultural Studies for a Global AgeNo ratings yet

- Reconsidering Religion, Law, and Democracy: New Challenges for Society and ResearchFrom EverandReconsidering Religion, Law, and Democracy: New Challenges for Society and ResearchNo ratings yet

- Theory X and Y - McGregor's Motivation TheoriesDocument6 pagesTheory X and Y - McGregor's Motivation Theorieskim cheNo ratings yet

- TDC SeminarDocument6 pagesTDC Seminarkim cheNo ratings yet

- Price: Factors Affecting Pricing DecisionDocument4 pagesPrice: Factors Affecting Pricing Decisionkim cheNo ratings yet

- Case Study No#4: This Study Resource WasDocument7 pagesCase Study No#4: This Study Resource Waskim cheNo ratings yet

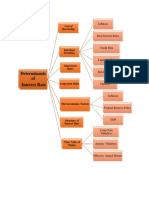

- Topic 2-Conceptual MapDocument1 pageTopic 2-Conceptual Mapkim cheNo ratings yet

- Statistical Sampling AuditingDocument5 pagesStatistical Sampling AuditingMuhammad Tuskheer Sohail AbidNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Development Economics Case Study Analysis 4 Dhruvi Kothari 1082180060 T.Y. Bsc. EconomicsDocument4 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Development Economics Case Study Analysis 4 Dhruvi Kothari 1082180060 T.Y. Bsc. Economicskim cheNo ratings yet

- BBS 2020 04 WijayaDocument12 pagesBBS 2020 04 Wijayakim cheNo ratings yet

- 13784-Topic 1Document1 page13784-Topic 1kim cheNo ratings yet

- DemystifyingtheChineseEconomy AuERDocument11 pagesDemystifyingtheChineseEconomy AuERJuan Pablo AragonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2-CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK-ANGTUDDocument4 pagesChapter 2-CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK-ANGTUDkim cheNo ratings yet

- Equity Related Policies Policies Specific To Regulation A Stock SalesDocument2 pagesEquity Related Policies Policies Specific To Regulation A Stock Saleskim cheNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 DisbursementsDocument20 pagesChapter 5 Disbursementskim cheNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Notes For DEC712S - 0Document21 pagesComprehensive Notes For DEC712S - 0Tanzina100% (1)

- Registration Ad BMBEDocument1 pageRegistration Ad BMBEkim cheNo ratings yet

- 15 GQ Ohx 1 Svuh SZW Ams 1 E4 Yud Vux 9 R WEhyDocument41 pages15 GQ Ohx 1 Svuh SZW Ams 1 E4 Yud Vux 9 R WEhykim cheNo ratings yet

- Reflection PaperDocument1 pageReflection Paperkim cheNo ratings yet

- Penalty and EffectivityDocument4 pagesPenalty and Effectivitykim cheNo ratings yet

- Senior Citizen LawDocument7 pagesSenior Citizen Lawkim cheNo ratings yet

- Contract Law For IP Lawyers: Mark Anderson, Lisa Allebone and Mario SubramaniamDocument14 pagesContract Law For IP Lawyers: Mark Anderson, Lisa Allebone and Mario SubramaniamJahn MehtaNo ratings yet

- BACC I FA Tutorial QuestionsDocument6 pagesBACC I FA Tutorial Questionssmlingwa0% (1)

- Abnormal Psychology Homework #4: Factors in Anxiety Disorders and Their TreatmentsDocument6 pagesAbnormal Psychology Homework #4: Factors in Anxiety Disorders and Their TreatmentsBrian ochiengNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Region: 3 Quarter, 2Document10 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Region: 3 Quarter, 2BEBERLIE GALOSNo ratings yet

- TC Speaking Like A PuritanDocument2 pagesTC Speaking Like A PuritanBro -HamNo ratings yet

- Phrases for Fluent English Speech and WritingDocument2 pagesPhrases for Fluent English Speech and WritingmolesagNo ratings yet

- Group 2 Selection ListDocument4 pagesGroup 2 Selection ListGottimukkala MuralikrishnaNo ratings yet

- Forgot Apple ID Password-CompressedDocument1 pageForgot Apple ID Password-CompressedNilesh NileshNo ratings yet

- Managing Bank CapitalDocument24 pagesManaging Bank CapitalHenry So E DiarkoNo ratings yet

- Material Fallacies ShortenedDocument56 pagesMaterial Fallacies ShortenedRichelle CharleneNo ratings yet

- National Institute of Technology Durgapur: Mahatma Gandhi Avenue, Durgapur 713 209, West Bengal, IndiaDocument2 pagesNational Institute of Technology Durgapur: Mahatma Gandhi Avenue, Durgapur 713 209, West Bengal, IndiavivekNo ratings yet

- STS Module 8Document16 pagesSTS Module 8Mary Ann TarnateNo ratings yet

- Quotes - From Minima MoraliaDocument11 pagesQuotes - From Minima MoraliavanderlylecrybabycryNo ratings yet

- Collapse of The Soviet Union-TimelineDocument27 pagesCollapse of The Soviet Union-Timelineapi-278724058100% (1)

- DRAFT Certificate From KVMRTv3 - CommentDocument2 pagesDRAFT Certificate From KVMRTv3 - CommentTanmoy DasNo ratings yet

- MSS RP 202Document6 pagesMSS RP 202manusanawaneNo ratings yet

- International Standards and Recommended Practices Chapter 1. DefinitionsDocument27 pagesInternational Standards and Recommended Practices Chapter 1. Definitionswawan_fakhriNo ratings yet

- Average Quiz BeeDocument21 pagesAverage Quiz BeeMarti GregorioNo ratings yet

- Ruta 57CDocument1 pageRuta 57CUzielColorsXDNo ratings yet

- Origin:-The Term 'Politics, Is Derived From The Greek Word 'Polis, Which Means TheDocument7 pagesOrigin:-The Term 'Politics, Is Derived From The Greek Word 'Polis, Which Means TheJohn Carlo D MedallaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2nd Evening Fall 2021Document2 pagesAssignment 2nd Evening Fall 2021Syeda LaibaNo ratings yet

- Obdprog mt401 Pro Mileage Correction ToolDocument6 pagesObdprog mt401 Pro Mileage Correction ToolYounes YounesNo ratings yet

- Churchil SpeechDocument5 pagesChurchil Speechchinuuu85br5484No ratings yet

- Salander Bankruptcy OpinionDocument52 pagesSalander Bankruptcy Opinionmelaniel_coNo ratings yet

- Who Are The MillennialsDocument2 pagesWho Are The MillennialsSung HongNo ratings yet