Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 Growth PDF

Uploaded by

Mohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 Growth PDF

Uploaded by

Mohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/269809954

Examining the Relationship Between Role Models

and Leadership Growth During the Transition to

Adulthood

Article in Journal of Adolescent Research · June 2015

DOI: 10.1177/0743558415576570

CITATIONS READS

9 537

3 authors, including:

David Rosch Daniel A. Collier

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Western Michigan University

57 PUBLICATIONS 305 CITATIONS 46 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Kalamazoo Promise View project

COVID and Higher Ed Research View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Daniel A. Collier on 28 May 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

576570

research-article2015

JARXXX10.1177/0743558415576570Journal of Adolescent ResearchBowers et al.

Article

Journal of Adolescent Research

1–23

Examining the © The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

Relationship Between sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0743558415576570

Role Models and jar.sagepub.com

Leadership Growth

During the Transition to

Adulthood

Jill R. Bowers1, David M. Rosch1,

and Daniel A. Collier1

Abstract

Leadership and developmental scholars have highlighted the need to enhance

youth leadership skills. Yet, research that explains youths’ perceptions of

how and when role models influences their leadership growth processes

is limited. To address these gaps and begin to develop an understanding of

youths’ perspectives, we employed a qualitative, grounded theory design

and interviewed emerging adults (N = 23) about their perceptions of their

own leadership development. Our analysis resulted in a role model–driven

framework for youth leadership development. This framework illustrates

participants’ descriptions of the leadership growth process between

adolescence and emerging adulthood, including the ways in which youths’

motivation to lead was facilitated by the qualities of relational role models,

their knowledge of opportunities, the relational role models’ beliefs in youths

potential, and the fact that they were inspired by positional role models.

Keywords

leadership development, role models, mentors, adolescents, emerging

adults, leadership growth

1University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, USA

Corresponding Author:

Jill R. Bowers, Department of Human and Community Development, University of Illinois at

Urbana–Champaign, 2029 Christopher Hall, MC-080, 904 W. Nevada, Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Email: bowers5@illinois.edu

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

2 Journal of Adolescent Research

Adolescents and emerging adults are the future leaders of our communities

and organizations, and longstanding concerns about the availability and effi-

cacy of good leadership among youth and adults in the United States have

continued seemingly unabated (Ashford & DeRue, 2012; Rosenthal, 2012;

Schwab, 2007). Adults have criticized contemporary youth (adolescents and

emerging adults) for lacking leadership qualities, or those that facilitate aca-

demic or occupational successes (e.g., by exhibiting poor interpersonal skills,

such as selfishness, or professional work ethic, such as laziness; Arnett,

2007). At the same time, scholars have, paradoxically, highlighted the critical

role of adult role models in youths’ leadership development (Astin, 1993;

Campbell, Smith, Dugan, & Komives, 2012; Dugan & Komives, 2007;

McNeill, 2010). In this study, we define role models as adults, or more expe-

rienced peers, who empower youth to develop as leaders by exhibiting cer-

tain qualities, behaviors, or successes. It is possible that how they have been

mentored, who their role models are, and the characteristics of the role mod-

els contribute to youths’ leadership deficiencies as highlighted by adults.

Research that helps us to understand the process by which role models influ-

ence leadership development among youth is limited. Furthermore, the vast

majority of the leadership literature focuses on adults’ perspectives. Less is

known about youths’ perspectives of the leadership growth process when, in

fact, youths’ voices may provide considerable insight into the ways in which

adults can define, teach, and mentor youth to grow as outstanding leaders in

their field. To address these gaps, we interviewed emerging adults about their

perceptions of their own leadership development between adolescence (i.e.,

experiences in high school) and emerging adulthood (i.e., experiences in col-

lege) and how their role models aided their development. The purpose of this

article was to gain a better understanding of how emerging adults describe

their own leadership growth and the processes by which role models facilitate

or constrain their leadership development.

Leadership Defined

Contemporary society calls almost all individuals to take on the responsibili-

ties of leadership in some context (Northouse, 2009), yet it has been argued

that “there are almost as many different definitions of leadership as there are

persons who have attempted to define it” (Bass, 1990, p. 11). Many observers

admit that they cannot clearly articulate a definition of leadership, but none-

theless know it when they see it (Rosch & Kuzel, 2010).

Social structures and work practices have shifted their focus from the

industrial paradigm of leadership that emphasizes hierarchy and control to a

more relationship-oriented focus that emphasizes trust, networks, and ethics

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 3

(Kezar, Carducci, & Contreras-McGavin, 2006; Komives, Lucas, &

McMahon, 2007; Rost, 1993). Furthermore, popular models have focused on

the emotional competencies required for creating effective relationships

(Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2002), described how leaders work with

groups to create adaptive change in organizations and society (Heifetz,

Grashow, & Linksy, 2009), and emphasized leader authenticity and integrity

(Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Still, there are some arguments about whether

leadership is a trait (Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1991; Stogdill, 1974), a skill

(Mumford, Marks, Connelly, Zaccaro, & Reiter-Palmon, 2000), a behavior

(McGregor, 1960), or the development of an influence-based relationship

(Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Nonetheless, relationships seem to be a common

denominator across the current leadership literature regardless of how schol-

ars are conceptualizing leadership.

Even when not clearly defined, many of the outcomes in the leadership

literature parallel the goals of educational systems (i.e., high school and col-

lege), such that outcomes often surround academic performance, occupa-

tional attainment, or success in adult roles. For example, research has shown

that the development of leadership and team-oriented competencies can help

adolescents and emerging adults to succeed in their communities and profes-

sional work settings after graduation (Astin & Astin, 2000). In addition,

employers wish universities spent more time educating their students on

issues of problem-solving, relationship development, communication skills

for teams, and ethical behavior (National Association of Colleges and

Employers, 2013). Based on the links between leadership traits, skills, behav-

iors, and outcomes related to community engagement and gainful employ-

ment in adulthood, we operationalized leadership when interviewing the

study participants as the skills, behaviors, or qualities that foster relationships

and achievements for individuals in positions of influence in community and

or occupational roles.

Youth as Primary Targets for Leadership Training

Individuals in late adolescence (approximately 17-18 years old) and emerg-

ing adulthood (18-25 years old) are often the target population for leadership

training programs as they are at pivotal points for establishing their own

community engagement and occupational trajectories. Concurrently,

research has shown rising rates of unemployment among this age group

(Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010) and lower retention rates among first-

time college students (United States Department of Education, 2010). In

addition, some adults critique adolescents and emerging adults for appearing

selfish, lazy, unambitious, and entitled (Arnett, 2007; Sacred Heart

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

4 Journal of Adolescent Research

University, 2006), although these are some of the personal and professional

skills that are least valued in educational and occupational settings. As the

professional environment increasingly calls for adults who can practice

influence from any position within an organization and build trusting and

interdependent relationships with diverse others (Seidman, 2007), navigat-

ing the transition to adulthood from this perspective of leadership develop-

ment is paramount.

Role Models

In apparent response to the need for leadership education, leadership edu-

cation efforts at colleges and universities have doubled, with more than

1,000 colleges and universities offering leadership education in some

form (Riggio et al., 2003), yet leadership is not always explicitly taught.

Some research has shown that leadership behaviors are more commonly

learned by observing and listening to others (Avolio, Reichard, Hannah,

Walumbwa, & Chan, 2009). Yet, such growth is often dependent on how

individuals engage with learning opportunities within their environment

over time.

Some leadership scholars assert that individuals develop as leaders when

they are in empowering environments, where adults and more experienced

leaders allow space for youth to mature and practice new skills (Komives,

Longerbeam, Owen, Mainella, & Osteen, 2006). Leadership role models,

therefore, are individuals in youths’ environments who might provide guid-

ance and mentoring to adolescents and emerging adults in the leadership

growth process and or facilitate an empowering environment. Researchers

have found significant predictive relationships between university students’

leadership capacity and their ability to engage in a mentorship process with

professionals on their campus (Campbell et al., 2012). In fact, two types of

role modeling in relation to mentorship that have been central in the leader-

ship literature include psychosocial (instilling a sense of competence, foster-

ing a healthy identity development, or providing guidance toward achievement

in some capacity) and career (e.g., vocational coaching or job skills; Daloz,

1999; Kram, 1985). At the same time, less is known about the qualities of role

models that facilitate leadership development or the processes by which the

relationship with the role model facilitates leadership development between

adolescence and emerging adulthood. Some research has shown that defi-

ciencies in mentor relational skills play a role in the demise of the youth-role

model relationship (Spencer, 2007). At the same time, more research is

needed that examines role model characteristics in relation to youths’ leader-

ship pathways.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 5

Goals of the Present Study

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of how and when

relationships between youth and their role models influence the ways in

which they grow as leaders between adolescence and emerging adulthood.

We chose emerging adults who were in leadership positions as our target

sample because emerging adults who were in positions to lead could speak on

their experiences as adolescents and discuss their leadership growth and the

conditions that facilitated it between adolescence and emerging adulthood.

To address the gaps in the literature, we employed qualitative, grounded the-

ory research to address the following questions:

Research Question 1: What are youths’ perceptions of the processes by

which role models influence leadership development between adoles-

cence and emerging adulthood?

Research Question 2: What are the conditions that facilitate the leader-

ship growth process?

Method

To address these questions, data were collected through qualitative research,

and the overall aim was to contribute to a comprehensive, grounded theory

about role models, youth, and leadership development. The present research

design was based on the work of Strauss and Corbin (1990), who have

asserted that theory evolves from the data, research questions largely focus

on process, and the research design becomes more focused throughout the

data collection process. Grounded theorists believe that coding involves the

proposition of categories and the various links between them, and a valida-

tion of the information through constant comparisons, thus “moving between

inductive and deductive thinking” (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, p. 111). Through

this process, researchers highlight concepts and group them into common

categories and subcategories, or properties of the categories. Each of these

stages of analysis are described in detail in this section.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected from a diverse sample of emerging adults who were

enrolled at a large, research-intensive university in the Midwestern United

States. We chose to interview emerging adults who were in college, so they

could speak about leadership growth experiences during adolescence and the

years in college that followed. Participants were involved by participating in

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

6 Journal of Adolescent Research

interviews (n = 23) and completing member checks (n = 11) where they

reviewed a four-paragraph summary of the results. Initial, open coding began

immediately after the first interviews. Following Strauss and Corbin’s (1990)

grounded theory model, we used axial coding and selective coding to analyze

each category further. Saturation occurred when we were confident that more

interviews or information from the participants would not provide additional

insights into the results of this study. This study involved simultaneous data

collection and analysis.

Participant recruitment. Participants were matriculated students who were

initially recruited through academic courses or student organizations that

included a spread of emerging adults across all undergraduate class stand-

ings (freshman through senior). Many youth do not even recognize their

own potential to employ leadership behaviors (Shertzer & Schuh, 2004). As

such, to explore the processes by which youth come to view certain adults

as role models who have influenced their leadership development between

adolescence and emerging adulthood, we employed purposeful sampling

and interviewed emerging adults who had been in positions to lead in col-

lege; purposeful sampling is a way to ensure information-rich cases are

included in the data (Patton, 2002). We intentionally chose to include stu-

dents who were actively involved in student organizations because we

wanted to explore the leadership growth process among emerging adults

who could recognize and articulate their leadership growth, potential,

behaviors, and the influence of role models. By selecting students who

were in positions to lead, we knew we could discuss these experiences in

the interviews if students struggled to recognize their own leadership devel-

opment. Purposeful, theoretical sampling is important to the grounded the-

ory process as grounded theory scholars believe that theoretical sampling

and the iterative process involved is important in developing a meaningful

understanding of all of the facets related to a category or concept (Glaser &

Strauss, 1967). We conducted interviews with all students who were

actively involved in student organizations and volunteered to participate.

Initial interviews with students from other countries or rural areas indicated

the potential for individual differences, so we purposefully recruited four

more students who were either from rural areas or who were international

students.

Incentives. Participants in this study were offered a $5 gift card to a food

establishment of their choice if they participated in initial interviews. Those

who completed member checks (n = 11) were presented with a $10 gift cer-

tificate to Amazon.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 7

Data management. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed by a tran-

scription company. The third author cross-checked the transcriptions and

assigned each participant a pseudonym (that they chose); these pseudonyms

were used in transcripts, memos, and written reports. All other identifying

information was removed. All transcriptions were uploaded into NVivo, a

software tool for managing qualitative data.

Sample Description

The college students (N = 23) who initially agreed to participate in initial

interviews included freshman (n = 3), sophomores (n = 6), juniors (n = 9),

and seniors (n = 5) from a variety of disciplines (i.e., biology; economics;

engineering; business; psychology; food science; health; Lesbian, Gay,

Bisexual, and Transgender [LGBT]/queer studies; secondary education; and

environmental sustainability). The study not only consisted of young women

(n = 11) and men (n = 12) who were largely U.S. citizens (n = 18) but also

included 5 who identified as international students from India (n = 4) or

China (n = 1). Of those who were U.S. citizens, the majority not only identi-

fied as White or Caucasian (n = 13) but also included students who identified

as Asian American (n = 4) and African American (n = 1).

Stages of analysis. The 60- to 120-minute interviews were appropriate for the

grounded theory methodology proposed here as they allow for rich insight,

discovery, and flexibility at the same time. In general, it is recommended that

20 to 30 participants are required for interviews in a grounded theory study

(Creswell, 2005; Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2007), although the sample in this

study relied on theoretical saturation.

Questions that we asked participants focused on how they had developed

as leaders since high school (e.g., Describe the role that others have had in

your own leadership growth since high school), their motivation to lead (e.g.,

How are you motivated to lead compared with your friends or others you

know?), and the qualities of good or bad leaders that influenced them (e.g.,

Identify someone who you believe is a good leader; describe how you know

them and why you believe that individual is a good leader). Initial, open cod-

ing began immediately after the initial interviews. In addition, the interviewer

wrote memos after each interview that included observations, potential bias,

and ideas about the interview and interviewee.

Data collection, memo writing, and coding occurred simultaneously. The

first and third authors were involved in the flexible open coding that occurred

during initial analysis of interviews. The second author provided feedback

and assisted coders with coming to agreements on categories and definitions

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

8 Journal of Adolescent Research

when there were discrepancies. Then, the categories that emerged and their

definitions allowed for axial coding, which began after we had completed 10

interviews. Axial coding is a detailed form of coding, which allows research-

ers to analyze phenomena that arise from open coding and provide a concep-

tual explanation for some process surrounding the phenomena; with axial

coding, “the grounded theorist selects one open coding category, positions it

at the center of the process being explored (as the core phenomenon, and then

relates other categories to it” (Creswell, 2005, p. 298). Following Strauss and

Corbin’s (1990) model, we used axial coding to link multiple categories and

subcategories that were identified during open coding, labeling possible

causal conditions (events that lead to the development of the phenomenon),

context (set of properties that pertain to the phenomenon), intervening condi-

tions (condition that facilitate or constrain action strategies), action/interac-

tion strategies (devised to respond to a phenomenon), and consequences

(outcomes) that surrounded each phenomenon. The axial coding stage is

where the researcher begins to analyze the process, discovering a paradigm

model. In this study, we identified links between emerging adults’ back-

grounds, experiences with role models, and how they grew (or did not grow)

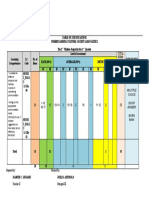

as leaders. For an example of our initial categories, see Table 1.

Then, we continued open and axial coding, but also began selective cod-

ing, including more details and validating or discounting cases. For example,

participants described positive qualities and negative qualities of adults with

whom they had interacted. Initially, we had subcategories for a variety of

positive or negative role model qualities. However, as our analysis became

more refined, we did not consider an observation of one negative or positive

action by an adult as characteristic of a role model; rather, we focused on

participants’ definitions of role models and their explanations as to why or

why not they considered these adults to be their role models along with the

nature of the relationship itself. Finally, we conducted formal member checks,

at which time participants who responded to the third authors’ emails (n = 11)

clicked on the link to review a four-paragraph summary of our analysis.

Researchers believe that the quality of the data improves through the member

checking process; even if participants disagree with the initial report of

research findings, this process helps the researchers to understand partici-

pants’ perspectives (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998).

Results

Our central research questions were designed for us to gain a better under-

standing of the processes by which role models influence youths’ leadership

development, specifically youths’ perceptions of the process between

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 9

Table 1. Example of an Initial Axial Coding Table During Coding for this Study.

Term Examples

Causal conditions Youths’ role models define success and leadership

and the opportunities that will help emerging adults to

achieve success and leadership.

Phenomenon Youth are influenced by relational and or

positional role models.

Context The number of role models emerging adults are

influenced by; opportunities for involvement;

number of people they are competing with; college

status (e.g., freshman, sophomore, junior, senior),

knowledge, and experience of role models—

What their role models know (or knowledge of role

models) and the experiences of their role models, who

their role models are and what they stand for?

Intervening conditions Role models define leadership and success, and they

display good or bad interpersonal skills, character

traits, work ethic, risk-taking behaviors, control,

or ethics, and youth find them credible or not

based on these characteristics.

Action/interaction Youth are motivated by role models they

believe are credible and/or they experience

barriers because of their role models’ actions,

characteristics, interpersonal skills, work ethic,

risk-taking behaviors, control, or ethics.

Consequences Youth grow as leaders; those who had leaders who

inspired them with good characteristics experience

the most positive changes in thoughts and actions

related to leadership or gain confidence in their own

leadership skills and recognize leadership as a process;

those who experienced the most barriers with role

models were not motivated to change or did not

understand how.

adolescence and emerging adulthood. Furthermore, we wanted to explore the

conditions that facilitated the leadership growth process. We include partici-

pants’ quotes from the interviews and member checks in this section to pro-

vide examples of how the categories and subcategories were derived through

the analysis. We conclude with a section on the data derived from the member

checks. We begin with the description of a conceptual model that emerged

from the data and depicts youths’ perceptions of the ways in which role mod-

els influenced their leadership development between adolescence and

emerging adulthood.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

10 Journal of Adolescent Research

Figure 1. A role model–driven framework for youth leadership development.

A Role Model–Driven Framework for Youth Leadership

Development

The data revealed that their role models influenced how participants defined

leadership and success, their knowledge of growth opportunities, their indi-

vidual awareness of their potential to become leaders, how they are inspired

to become leaders, their pursuit of opportunities, and their levels of involve-

ment. The analysis provided insight into the ways in which relational role

models (i.e., parents, friends, family, high school teachers, coaches, profes-

sors, or other mentors with which they have a personal relationship) provided

the foundation for their leadership development by displaying good leader-

ship qualities. As the relational role models displayed good leadership quali-

ties, youth were motivated to develop as leaders. The relational role models

helped youth by providing them with knowledge of opportunities for leader-

ship development, as well as a belief in their own potential as leaders. As

participants became knowledgeable and believed in their own potential, they

got involved in leadership roles and were often inspired by positional role

models (i.e., college professors; institutional, organizational, community, and

world leaders that they learn from but with whom they do not have a relation-

ship). See Figure 1 for a graphic representation of the nature of participants’

leadership growth.

According to participants, they trusted, respected, learned, and listened

most to role models who displayed professional work ethic (e.g., initiative,

drive, persistence), good interpersonal skills (e.g., communicating with con-

fidence, listening), and positive character traits (e.g., respectful, responsible,

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 11

positive attitude, tolerant). Although some participants viewed role models’

“weaknesses as a learning opportunity” (Britney), many acknowledged get-

ting frustrated and discouraged by role models who did not exhibit qualities

that youth perceive to be those representative of good leadership. Ben said

that he and others his age often “struggle with role models who lack certain

characteristics [because] we want someone who can influence us to be better

than who we already are.” Thus, the personal qualities that the role model

employs are critical to the influence the role model had on youths’ leadership

growth. These qualities are, in essence, what makes role models credible and

trustworthy leaders through the eyes of youth. Eve summarized the words of

others when she stated, “if role models want successful young adults, they

must realize their success is a reflection of their guidance.”

Professional work ethic. Professional work ethic was the most commonly

coded subcategory within relational role models’ qualities. Many partici-

pants’ echoed Ingrid who stated, “Nobody will be inspired by someone who

has no work ethic or professional skills, so I don’t think these types of people

will be role models in the first place.” Hana said,

Anyone can be complacent, not showing any initiative, working hard, etc. . . .

no one admires this because it’s often in the natural state. However, when we

see what can be accomplished with good work ethic, [ . . . ] people want to

work equally hard.

Many participants viewed hard work and initiative as minimal require-

ments of a good leader. Participants said, “as a leader you have to take on

. . . you’re willing to take on more responsibilities” (Allison), “show more

involvement” (Britney), “take initiative” (Cassie), and “take on more than the

rest, have your workload be a little bit more” (Peter).

Interpersonal skills. Participants in this study also discussed interpersonal

skills when asked to think about someone they know and what makes them a

good leader. For example, Cassie stated that individuals trust leaders who are

empathetic, such as those who are able to problem solve, as well as “read a

group and know how they work” and listen to their ideas. She emphasized the

importance of knowing your audience and being able to adapt. Similarly, Abe

said that “being charismatic . . . and working well with people” in addition

to “being empathetic and seeing [things] through your subordinates eyes” is

important. Listening skills played a key role for participants. For example,

Peter stated that one of his role models was “always trying to listen to people,

not just say what’s on his mind. He’ll listen first, absorb what they’re trying

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

12 Journal of Adolescent Research

to say, and then say something back.” Displaying good interpersonal skills

was a quality that youth valued in their role models and others whom they

viewed as leaders.

Positive character traits. There were several character traits that participants

discussed as important to the influence of the relational role model or the for-

mation of the relationship between youth and role models with whom they

did not already have a relationship. For example, good leaders “have posi-

tive personalities” (Gail), “have respect for us” (Ben), “consider themselves

equal to the people they’re leading, but just have to take more responsibility”

(Cassie), and “cover everyone equally” (Ben). Some of the character traits

were mentioned because they were motivated by a role model who displayed

such traits. For example, Gail was inspired by a high school teacher who

influenced her students to do their best. She said that this teacher was confi-

dent and listened, but she was also positive and respectful to all people and

subsequently, people turned to her when they had a problem. Youth may fear

rejection and thus, a role model with a positive attitude may help increase

comfort and confidence when deciding to approach them. Ingrid said, “It is

important to have a mentor who you can go to for help when you are feeling

discouraged, and that person should be someone who has a positive attitude

and will help you get back on track.”

Eve said,

if students receive positive feedback from someone they trust, they’ll thrive.

And if you work very hard with a role model, but they’re negative or don’t

acknowledge your work, you feel very dejected and are probably less likely to

perform at your full aptitude from that point forward.

Again, many participants also respected mentors who lead by example. If

their role models, for example, considered it a sign of disrespect to be late for

a class, they expected the teacher or professor to give them the same respect.

For example, Ben said that if a class started at 8:30 and the professor expects

everyone to be there by 8:30 (if not before), then, he or she should not come

walking in at 8:35.

Such focus on respect was evident in each discussion with participants

who mentioned this as an important leadership quality. Sometimes, respect

was earned by giving it and other times, participants discussed the respect

they had for role models who displayed other positive character traits, such as

positivity and tolerance.

The foundations that the relational role models provided for participants’

leadership development were often indirect, such that they did not say, “here’s

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 13

how to be a leader.” Instead, they modeled traits that led youth to incorporate

learned values and behaviors. For example, Hana said, “While they [my par-

ents] did not directly inspire me to be a leader, they did teach me to behave

positively and to work hard.”

Relational role models influence youth’s motivation for leadership development. As

the role model displayed good leadership qualities, role models with whom

youth had a relationship influenced youths’ motivation for leadership devel-

opment. The data revealed the significance of a personal relationship between

youth and their role models in helping youth to define leadership and boost-

ing their desire for leadership development. For example, Ingrid said, “I don’t

personally learn well from people who I am not closely connected to . . .

mentors who I have close relationships with have shaped me and influenced

my motivation and goals.” Many other participants in this study echoed Brit-

ney’s comments. She stated,

I would not have grown as a leader if I wasn’t encouraged by my own teachers,

friends’ parents, and my own parents. Their belief in me as a leader also helped

them provide me with more opportunities to develop as a leader.

Because some youth talked about their parents or family members as most

influential on their leadership growth process and others discussed the quali-

ties that influenced the relationship between youth and their leadership role

models, we believe that it may be the combination of the youths’ perspectives

of leadership qualities displayed by the role model and the relationship itself

that supported the leadership development process for the youth in this study.

Nonetheless, the relational aspect appeared to be a critical component of the

leadership growth process. Thus, we believed that it was important to distin-

guish these roles models from those with whom youth did not have a relation-

ship. As such, we defined relational role models as parents, friends, family,

high school teachers, coaches, professors, or other mentors with whom they

had a personal relationship.

According to participants in this study, relational role models provided the

foundation for their leadership abilities. For example, Jake talked about his

dad and said, “my father was by far the biggest influence on my leadership

development.” Others, such as Britney, Abe, and Cassie described high

school teachers or coaches as role models who played an essential role on

their leadership development. Some participants mentioned relational role

models they had had in college (e.g., professors or those who were officers of

a student organization in which they were involved). For example, Curt dis-

cussed being influenced by a friend, who had more leadership experience as

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

14 Journal of Adolescent Research

the leadership chair for a university service fraternity for which he was

involved. The relationship with the role model(s) facilitated youths’ knowl-

edge of leadership qualities, opportunities, and their belief in their own abili-

ties to follow suit.

Knowledge is gained of opportunities and belief in their own potential. For partici-

pants to learn about opportunities and believe in their own potential as lead-

ers, they had at least one (and sometimes many) relational role models who

facilitated such knowledge and beliefs. For example, Hana said, “my greatest

time of growth was when I surrounded myself with people whom I consid-

ered to be good leaders. These people motivated me, helped me find my

intrinsic motivation, and encouraged me to keep up with them.” As such,

participants’ knowledge of opportunities and belief in their own potential

flourished or was constrained by a variety of individual and contextual fac-

tors (e.g., ethnicity, gender, where they grew up, their college status). For

example, Mike said, “If one is a minority, then he has the stigma engrained

into him from birth that he must work harder than others to prove himself.

That is how it was for me.” Although some participants considered them-

selves advantaged because they were a part of a dominant group, a few others

acknowledged stereotypes that might make it difficult for others. For exam-

ple, Ben who grew up in a rural area said most of his role models were men.

He said, “When I was younger, I can remember thinking about who would be

considered ‘in charge’ and it was always a male.” As such, Ben’s capacity for

leadership may have been influenced by social policies that encouraged him

as a young man, and it is possible that his female peers may not have been

encouraged in the same manner.

Some participants had opportunities to be influenced by a number of rela-

tional role models, yet others persevered because they had just one relational

role model who inspired their knowledge of opportunities and belief in their

own potential. For example, Gail was raised by a single mother who immi-

grated to the United States and did not have a college education and thus,

Gail experienced barriers to leadership development surrounding class and

family structure. She was a first-generation college student and although she

viewed her mother as a role model, the knowledge that her mother could

provide about leadership opportunities was limited. Yet, she went on to pur-

sue college and leadership opportunities at college because she had a cousin

who went to optometry school. Her career path modeled that of her cousin’s

and she said he gave her hope that she was capable and she was “impressed

and motivated by his success and hard work.”

Indeed, the data revealed that participant’s awareness of leadership oppor-

tunities and their own potential were often dependent on the intersection

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 15

between their relational role models and individual and contextual factors. It

was often the case that the knowledge and beliefs of the role models in a

given culture or area influenced participants’ own knowledge and beliefs.

Even those that did not discuss their own advantages or disadvantages with

respect to knowledge of opportunities and belief in their own potential

described their perceptions of how such differences influenced others’ leader-

ship growth. For example, Eve said,

Everyone likes to hear a good success story because it makes them feel less

guilty about the huge gap in educational quality and opportunities for those of

less privileged genders, races, and socio-economic backgrounds. I don’t think

less privileged kids are any less inspired by their own personal leadership role

models. But, the quality of that role model greatly varies from demographic to

demographic.

Youth is inspired by positional role models and actively pursue opportunities. The

relational role models with good leadership qualities facilitated participants’

own knowledge and beliefs, yet the data in this study revealed that to grow,

youth become inspired by positional role models as they actively pursue

opportunities for involvement. Based on participants’ descriptions of indi-

viduals who they considered role models but they did not necessarily know

personally, we defined positional role models as college professors, institu-

tional, organizational, community, and world leaders that they learn from but

with whom they do not have a relationship. Jake articulated this when asked

specifically about differences between his relational and positional role mod-

els in the member checks phase of this study. He said,

I think that relational role models have the greater impact on our willingness

and ability to serve as a leader, but positional role models provide the inspiration

for us to strive for higher levels of leadership and greater levels of success

within our positions.

Some participants believed that their transition from learning from rela-

tional models to closely observing positional role models occurs over time

and possibly, with age. In essence, their relational models were still consid-

ered important influences, but less so as they “grow out” of them or observe

positional role models more closely aligned with their aspirations in life. For

example, Eve said,

Growing up, I always idolized my teachers and parents. But when you get

older, you realize that they’re a little out of touch and their magic fades. By the

time I was 18, I think all of my major sources of inspiration were people that I

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

16 Journal of Adolescent Research

had never met. While I do look up to my parent, teachers, and professors for

advice and guidance, I don’t look to them for leadership inspiration. They will

always be a great tool in getting leadership advice, but in terms of the people

that I would want to mold my personal leadership trajectory off of, I would

look up more to Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and other people that were

once normal and unimportant like me. That’s way more inspiring than my

parents telling me that I’m great.

In summary, the data revealed that the relationship between youth and

their relational role models provided the foundation for their growth. The

relationship and its influence on participants’ motivation for leadership

growth were facilitated by the qualities that the role models exhibited (i.e.,

professional work ethic, interpersonal skills, and positive character traits).

Once participants learned of opportunities to get involved and believed in

their own potential, they actively pursued those opportunities. As they got

more involved, many participants were also inspired by positional role mod-

els, who had qualities, behaviors, or outcomes that they believed extended

the capabilities of their relational role models. As such, the relationships that

youth have with role models helped to define leadership and success and set

the stage for further development. From there, leadership skills are “continu-

ously evolving” (Britney).

Member Checks

In this study, we emailed a link to a four-paragraph summary of the results

and asked participants to validate or refine our interpretations. Many of the

participants, who completed the member checks (n = 11) provided feedback,

such as “I agree with the above statement because . . . ” or “I completely

agree with this” and “I find this to be very true” with descriptions and expla-

nations in the comments sections below each paragraph. Participants’ favor-

able responses to the one page summary and their additional comments

provided the validation for the constructs. Of the few that discounted any of

our interpretations, their disagreements surrounded the significance of indi-

vidual and contextual factors in relation to the opportunities the emerging

leader learns about from his or her role model(s). Yet, many participants

agreed with the information in this section and elaborated or included exam-

ples to provide further validation. As such, we did not refine our interpreta-

tions in this area, and we believe participants’ own perceptions are limited to

their unique experiences. These experiences and unique leadership pathways

deserve more attention in the literature (e.g., similarities and differences in

social norms, expectations, opportunities, and role models in various geo-

graphic locations or cultures). Regardless, no new properties or dimensions

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 17

emerged from member checks, and we became even more confident that the

data analysis included enough details, yet was comprehensive enough that it

accounted for much of the possible variability among participants’ responses.

We, therefore, determined after completing member checks that we had

reached theoretical saturation and no new data needed to be collected.

Discussion and Implications

Our study focused on youth leadership growth processes, youths’ perceptions

of how their role models came to be their leadership-oriented role models,

and the ways in which certain role models influenced their leadership

development between adolescence and emerging adulthood. We inter-

viewed emerging adults who described their leadership growth between

adolescence and emerging adulthood. A role model–driven framework for

youth leadership development emerged from data, and this model can be

used to discriminate the influence of relational role models and positional

role models. According to the emerging adult participants, relational role

models seem to provide a foundation of confidence within the youth, and

aid in recognizing the potential for engagement in student or service orga-

nizations. Once such a foundation is created, inspiration from positional

role models may then provide energy and momentum toward increased

engagement and growth beyond what relational role models often provide.

Perhaps most critical to the youth-role model relationship for emerging

adults in this study were the positive leadership behaviors and traits pos-

sessed by relational role models. Indeed, these findings indicate that youth

learn best from and listen to role models who display positive characteris-

tics (i.e., professional work ethic, interpersonal skills, and positive charac-

ter traits), and the positive leadership qualities exhibited by these role

models provide the foundation for the youth-role model relationship.

Moreover, some participants attributed their motivation for leadership

development to their role models. It is possible that the qualities their role

models possessed facilitated youths’ intrinsic motivation to develop as

leaders, such that youths’ role models provided informational support that,

in turn, facilitated self-determination and competence as leaders, rather

than control over the youth, which has been found to lower self-determina-

tion and undermine intrinsic motivation (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 2001).

We provide implications for research and provide practical suggestions for

role models, school or university administrators, or those who work in

organized youth programs by focusing here on leading by example and

motivating youth, as well as individual and contextual factors that should

be considered in future research and practice.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

18 Journal of Adolescent Research

Leading by Example and Motivating Youth

The findings from this study possess several important implications for those

involved in youth development programs and invested in youths’ futures.

First, the data revealed that positive leadership qualities displayed by indi-

viduals who are in positions to lead youth (e.g., program staff, faculty, interns,

coaches, or volunteers) are a key to the youth-role model relationship and,

subsequently, youth leadership development. Adults in positions of influence

who lack initiative, interpersonal skills, and positive character traits may

impede youth’s knowledge of opportunities, or their confidence to try out

various leadership positions. As such, it is especially important for adults to

display positive leadership qualities that they wish to see in youth before

youth will learn to develop as leaders with those qualities. To ensure that

those who work with youth are displaying positive leadership qualities and

leading by example, leaders, themselves, may need explicit leadership train-

ing (e.g., by requiring staff or volunteers who are in direct service positions

to read a book or attend a workshop on leadership qualities that they are

expected to exhibit). Administrators may falsely assume that their organiza-

tions’ leaders will exhibit such qualities. With more explicit leadership train-

ing for staff and volunteers, however, youths’ potential role models could

become aware of their strengths and areas for potential growth. Moreover,

such training could facilitate a culture of leadership within organizations or

institutions that serve youth (e.g., through common leadership-focused lan-

guage or naturally occurring accountability that occurs as a result of aware-

ness of one’s own leadership styles, as well as organizational expectations).

Second, developmental scholars have found that the development of ini-

tiative plays a critical role in positive youth development, and opportunities

for such growth often occur in the context of organized youth activities or

school (Larson, 2000). Larson believes that within these contexts, youth learn

when they experience a combination of intrinsic motivation and concentra-

tion. It is possible that the qualities displayed by role models with whom

emerging adults could potentially have a relationship can facilitate or con-

strain their initiative, intrinsic motivation, and ability to pay attention. This

could be tested in quantitative studies that examine the association between

role model characteristics, motivation, and the youth-role model relationship,

and such research could inform curricula and training for youth program

leaders.

Finally, leadership and developmental scholars assert that the contempo-

rary work force requires skills such as collaboration, strategic thinking, orga-

nization, and others that are not measured in many westernized countries in a

way that influence youths’ work or college pathways (Larson, Wilson, &

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 19

Mortimer, 2002). If youth are expected to exhibit good leadership qualities

and such qualities often dictate their ability to obtain or maintain employ-

ment, perhaps evidence of the development of leadership skills could be

more explicitly taught and utilized as measures of potential future success.

Considering Individual and Contextual Factors

Our findings also indicate that various individual and contextual factors (e.g.,

ethnicity, gender, college status, geographic location of where they grew up)

may influence role models’ knowledge and beliefs about leadership and, subse-

quently, knowledge and opportunities for youth. For example, the analysis

revealed that young men in this study who grew up in rural areas may be at an

advantage when compared with the young women because of the social policies

that reinforce gendered behaviors. As such, young women in rural areas may

benefit from female role models who have knowledge of opportunities for

young women to get involved, or have, themselves, sought positions or careers

that facilitate leadership growth. More research, however, is needed on these

factors. Through quantitative research and a larger sample of youth, researchers

could better address individual differences as a function of gender, region, social

class, and culture. Practitioners could, subsequently, refine leadership training

practices or develop programs to help specific populations. For example, young

women in rural areas may benefit from structured mentoring systems while they

are in high school.

Limitations

We are able to provide a role model–driven framework for youth leadership

development and several implications based on our work with emerging

adults, yet our study was not without limitations. Our grounded theory was

based on the values and beliefs of the 23 emerging adults who participated,

and while this group was diverse, it should not be seen as necessarily repre-

sentative of the broad demographic of emerging adults in contemporary soci-

ety. We intentionally chose a sample of youth who were leaders in some

capacity, so that they could discuss their experiences about their leadership

development. Further research that includes a broader representation of

emerging adults in regards to demography and geography is warranted. The

inclusion of younger adolescents, who might be currently developing rela-

tionship with potential mentors, could provide for a more refined model as well,

especially if this research could be combined with longitudinal analysis of youth

leadership through their elementary, high school, and college years. Although

exploratory, our findings surrounding individual and contextual diversity high-

light a need to include individual differences in studies of leadership growth.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

20 Journal of Adolescent Research

Moreover, our results were informed by college students who have already

succeeded in some ways by simply being enrolled in an institution of higher

education. As such, future research should examine the role model–driven

framework and the influence of youth-role model relationships on non-uni-

versity populations.

Conclusion

This research provides an understanding of youth leadership growth processes

and contributes to the developmental and leadership literature by highlighting

the ways that role models influenced the leadership development of emerging

adults in this study. Our analysis resulted in a role model–driven framework

for the leadership growth process between adolescence and emerging adult-

hood, emphasizing the importance of relational role models in youths’ knowl-

edge of opportunities and belief in their potential. Additionally, positional role

models inspired youth to actively pursue opportunities that enhanced their

leadership growth. This research can be used in future efforts involving lead-

ership training for emerging adults, as well as adults who work with youth to

ensure more congruity between employers’ and other adults’ expectations and

emerging adults’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors surrounding leadership.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publi-

cation of this article.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Suffering, selfish, slackers? Myths and reality about emerging

adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 23-29. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-

9157-z

Ashford, S. J., & DeRue, D. S. (2012). Developing as a leader: The power of mind-

ful engagement. Organizational Dynamics, 41, 146-154. doi:10.1016/j.org-

dyn.2012.01.008

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Astin, A. W., & Astin, H. S. (2000). Leadership reconsidered: Engaging higher edu-

cation in social change. Battle Creek, MI: W.E. Kellogg Foundation.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to

the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 315-338.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 21

Avolio, B. J., Reichard, R. J., Hannah, S. T., Walumbwa, F. O., & Chan, A. (2009). A

meta-analytic review of leadership impact in research: Experimental and quasi-

experimental studies. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 764-784. doi:10.1016/j.

leaqua.20000999.06.006

Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, &

managerial applications. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2010). Employment and unemployment among youth.

Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/youth.nr0.htm

Campbell, C. M., Smith, M., Dugan, J. P., & Komives, S. R. (2012). Mentors and col-

lege student leadership outcomes: The importance of position and process. The

Review of Higher Education, 35, 595-625. doi:10.1353/rhe.2012.0037

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluat-

ing quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Education.

Daloz, L. A. (1999). Mentor: Guiding the journey of adult learners. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic moti-

vation in education: Reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research,

71, 1-27. doi:10.3102/00346543071001001

Dugan, J. P., & Komives, S. R. (2007). Developing leadership capacity in college stu-

dents: Findings from a national study. A report from the Multi-Institutional Study of

Leadership. College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies

for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R. E., & McKee, A. (2002). Primal leadership: Realizing the

power of emotional intelligence. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership:

Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over

25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership

Quarterly, 6, 219-247.

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linksy, M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership:

Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard Business Press.

Kezar, A. J., Carducci, R., & Contreras-McGavin, M. (2006). Rethinking the “L”

word in higher education: The revolution in research in higher education (Vol.

31). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kirkpatrick, S. A., & Locke, E. A. (1991). Leadership: Do traits matter? The Executive,

5, 48-60.

Komives, S. R., Longerbeam, S. D., Owen, J. E., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L.

(2006). A leadership identity development model: Applications from a grounded

theory. Journal of College Student Development, 47, 401-418. doi:10.1353/

csd.2006.0048

Komives, S. R., Lucas, N., & McMahon, T. (2007). Exploring leadership: For col-

lege students who want to make a difference (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

22 Journal of Adolescent Research

Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American

Psychologist, 55, 170-183.

Larson, R. W., Wilson, S., & Mortimer, J. T. (2002). Conclusions: Adolescents’

preparation for the future. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12, 159-166.

doi:10.1111/1532-7795.00029

McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterprise. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

McNeill, B. (2010). The important role non-parental adults have with youth learn-

ing leadership. Journal of Extension, 48. Retrieved from http://www.joe.org/

joe/2010october/tt4.php

Mumford, M. D., Marks, M. A., Connelly, M. S., Zaccaro, S. J., & Reiter-Palmon, R.

(2000). Development of leadership skills: Experience and timing. The Leadership

Quarterly, 11, 87-114.

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2013). Job outlook 2013.

Bethlehem, PA: Author.

Northouse, P. G. (2009). Introduction to leadership concepts and practice. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). A call for qualitative power analyses.

Quality & Quantity, 41, 105-121. doi:10.1007/s11135-005-1098-1

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A

personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1, 261-283.

doi:10.1177/1473325002001003636

Riggio, R. E., Ciulla, J. B., & Sorensen, G. J. (2003). Leadership education at the

undergraduate level: A liberal arts approach to leadership development. In S. E.

Murphy & R. E. Riggio (Eds.), The future of leadership development (pp. 223-

236). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Rosch, D. M., & Kuzel, M. L. (2010). What do we mean when we talk about leader-

ship? About Campus, 15, 29-30.

Rosenthal, S. A. (2012). National Leadership Index 2012: A National Study of

Confidence in Leadership. Cambridge, MA: Center for Public Leadership,

Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved from http://www.centerforpublicleadership.

org/

Rost, J. C. (1993). Leadership for the 21st century. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Sacred Heart University. (2006). Majority of Americans cite sense of entitlement

among youth, says national poll. Retrieved from http://www.prnewswire.com/

news-releases/majority-of-americans-cite-sense-of-entitlement-among-youth-

says-national-poll-56425377.html

Schwab, N. (2007). A national crisis of confidence. U.S. News & World Report,

143, 46.

Seidman, D. (2007). How we do anything means everything: In business and in life.

Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Shertzer, J. E., & Schuh, J. H. (2004). College student perceptions of leadership:

Empowering and constraining beliefs. NASPA Journal, 42, 111-131.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

Bowers et al. 23

Spencer, R. (2007). It’s not what I expected: A qualitative study of youth men-

toring relationship failures. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 331-354.

doi:10.1177/0743558407301915

Stogdill, R. M. (1974). Handbook of leadership: A survey of theory and research.

New York, NY: Free Press.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory

procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Taylor, S. J., & Bogdan, R. (1998). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A

guidebook and resource (3rd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley.

United States Department of Education. (2010). National Center for Education

Statistics—Fast facts. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.

asp?id=40

Author Biographies

Jill R. Bowers is a researcher in the Family Resiliency Center in the Department of

Human and Community Development at the University of Illinois at Urbana–

Champaign. Her research focuses on online program development and evaluation,

specifically online positive youth development programs for adolescents and emerg-

ing adults.

David M. Rosch serves as an assistant professor in the College of Agriculture,

Consumer, and Environmental Sciences (ACES) at the University of Illinois at

Urbana–Champaign. His particular areas of interest include programmatic training in

youth leadership development and the accurate assessment of leadership effective-

ness. He earned his doctorate in higher education administration from Syracuse

University, a master’s in student affairs in higher education from Colorado State

University, and a bachelor’s degree from Binghamton University, NY.

Daniel A. Collier is a graduate student in the Education Policy, Organization and

Leadership doctoral program. He is particularly interested in student leadership devel-

opment, ethical leadership practices of administration, and evaluation of educational

workplace policy, and currently serves as a research assistant in the Illinois Leadership

Laboratory through the Agriculture Education Department.

Downloaded from jar.sagepub.com at UNIV OF ILLINOIS URBANA on May 27, 2015

View publication stats

You might also like

- Leadership Reckoning: Can Higher Education Develop the Leaders We Need?From EverandLeadership Reckoning: Can Higher Education Develop the Leaders We Need?Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Benefits of A Long-Lens Approach To Leader DevDocument13 pagesThe Benefits of A Long-Lens Approach To Leader DevacorderoNo ratings yet

- Hoch - Do Ethical Authentic and Servant Leadership Explain Variance Above and Beyond Transformational LeadershipDocument29 pagesHoch - Do Ethical Authentic and Servant Leadership Explain Variance Above and Beyond Transformational Leadershipallis eduNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals 20 Knowledge 20 of 20 LeadershipDocument5 pagesFundamentals 20 Knowledge 20 of 20 LeadershipAmrit PatnaikNo ratings yet

- TESIS Heinzerling 2018Document30 pagesTESIS Heinzerling 2018MarcelaNo ratings yet

- The Glass Ceiling and Executive Careers Still An Issue For Pre-Career WomenDocument16 pagesThe Glass Ceiling and Executive Careers Still An Issue For Pre-Career WomenGabriela BorghiNo ratings yet

- Leadership Study BenchmarkingDocument7 pagesLeadership Study BenchmarkingPaula Jane MeriolesNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals 20 Knowledge 20 of 20 LeadershipDocument5 pagesFundamentals 20 Knowledge 20 of 20 LeadershipmalikNo ratings yet

- Promoting Positive Youth Development Through Teenagers-as-Teachers ProgramsDocument25 pagesPromoting Positive Youth Development Through Teenagers-as-Teachers ProgramsFeli S.No ratings yet

- K Cognitive and Social Processes in EarlyDocument17 pagesK Cognitive and Social Processes in EarlyMbak KatiniNo ratings yet

- Leadership by GenderDocument8 pagesLeadership by GenderAlexandru PrisecaruNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Leadership Expectations On Gendered Leaders' BehaviorDocument8 pagesCross-Cultural Leadership Expectations On Gendered Leaders' BehaviorCarolina Gomes de AraújoNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Literature Review Background of The StudyDocument60 pagesThe Problem and Literature Review Background of The StudyDandyNo ratings yet

- Bridging Generations Applying Adult LeadDocument17 pagesBridging Generations Applying Adult LeadAngie Viviana EspitiaNo ratings yet

- Developing Leadership For Life Outcomes From A Collegiate Student Alumni Mentoring Program (2014)Document12 pagesDeveloping Leadership For Life Outcomes From A Collegiate Student Alumni Mentoring Program (2014)Konika SinghNo ratings yet

- AdolLead 2022 PPS in PressDocument45 pagesAdolLead 2022 PPS in Presserichjanegonzagagarcia493No ratings yet

- Hoch Bommer Dulebohn WuDocument30 pagesHoch Bommer Dulebohn WuKrishnanand RavikumarNo ratings yet

- Leadership DevelopmentDocument312 pagesLeadership Developmentherryapt100% (2)

- Organizational Behavior LEADERSHIPDocument33 pagesOrganizational Behavior LEADERSHIPShyam TarunNo ratings yet

- The Future of Leadership Development: It's Vertical!Document8 pagesThe Future of Leadership Development: It's Vertical!Stefania Padilla RamirezNo ratings yet

- Applied Article Analysis Voskoyan RobertDocument5 pagesApplied Article Analysis Voskoyan RobertRobert VoskoyanNo ratings yet

- Guay 2015Document12 pagesGuay 2015NURUL AIN MOHD NASIBNo ratings yet

- How Do They Manage? An Investigation of Early Childhood LeadershipDocument25 pagesHow Do They Manage? An Investigation of Early Childhood LeadershipNon AisahNo ratings yet

- Lived Experiences of Student LeadersDocument6 pagesLived Experiences of Student LeadersIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Future OrientationDocument29 pagesFuture OrientationY VismitanandaNo ratings yet

- Session 1 - Romance of LeadershipDocument8 pagesSession 1 - Romance of LeadershipMai MaiNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Adult Development Theories: Overviews and OverlapsDocument18 pagesLeadership and Adult Development Theories: Overviews and OverlapsDaniel AretasNo ratings yet

- The Art and Science of Leadership 6e Afsaneh Nahavandi Test BankDocument5 pagesThe Art and Science of Leadership 6e Afsaneh Nahavandi Test BankIvan Olegov0% (2)

- Student and Youth Leadership: A Focused Literature Review: AuthorDocument21 pagesStudent and Youth Leadership: A Focused Literature Review: AuthorL G Pangahin AvenidoNo ratings yet

- Leadership and The GiftedDocument12 pagesLeadership and The GiftedVideo KlipNo ratings yet

- Social and Emotional Learning in Adolescence - Testing The CASEL Model in A Normative SampleDocument30 pagesSocial and Emotional Learning in Adolescence - Testing The CASEL Model in A Normative Sampleina safitriNo ratings yet

- Causadias, Salvatore, & Sroufe, 2012Document11 pagesCausadias, Salvatore, & Sroufe, 2012GriselNo ratings yet

- 1-7-LQ-2015-To Whom Does Transformational Leadership Matter MoreDocument12 pages1-7-LQ-2015-To Whom Does Transformational Leadership Matter MoreTàii ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior Project ON From Transactional To Transformational Leadership: Learning To Share The VisionDocument13 pagesOrganizational Behavior Project ON From Transactional To Transformational Leadership: Learning To Share The VisionShashank KhareNo ratings yet

- Leadership Styles - Organizational Behavior and Human RelationsDocument9 pagesLeadership Styles - Organizational Behavior and Human RelationsSriram AiyaswamyNo ratings yet

- The Untold Stories of Student LeadersDocument10 pagesThe Untold Stories of Student LeadersAna AlcasidNo ratings yet

- Are Leaders Born or MadeDocument3 pagesAre Leaders Born or MadeSanchiNo ratings yet

- Ssaucedofalagan Lab Paper 4Document7 pagesSsaucedofalagan Lab Paper 4api-447525145No ratings yet

- Students StandardsDocument27 pagesStudents StandardsHoney Jade Ceniza OmarolNo ratings yet

- Mentoring and Leader Identity Development: A Case StudyDocument32 pagesMentoring and Leader Identity Development: A Case StudyManuel Hugo Luarte JaraNo ratings yet

- RRL Final 1Document2 pagesRRL Final 1sherlynmamac98No ratings yet

- Beyond Knowledge and Skills - Exploring Leadership Motivation As ADocument19 pagesBeyond Knowledge and Skills - Exploring Leadership Motivation As Amayan clerigoNo ratings yet

- Howard Walsh 2011Document18 pagesHoward Walsh 2011Sannan Asad ArfeenNo ratings yet

- Leadership DevelopmentDocument15 pagesLeadership Developmentamos wabwileNo ratings yet

- Transformational Leadership Practice of Academic Heads of Private Colleges in LagunaDocument10 pagesTransformational Leadership Practice of Academic Heads of Private Colleges in LagunaIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- Reference9 2Document3 pagesReference9 2Gabrieli AlvesNo ratings yet

- Bsoa Loja Et Al Done FinalDocument37 pagesBsoa Loja Et Al Done FinalZainahl Danica DangcatanNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Youth DevelopmentDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Youth Developmentc5qz47sm100% (2)

- Walumbwa Schaubroeck 2009 JAPDocument13 pagesWalumbwa Schaubroeck 2009 JAPNad GhazaliNo ratings yet

- Leadershipdevelopmentartice SMjouranl AADocument3 pagesLeadershipdevelopmentartice SMjouranl AATusharr AnanddNo ratings yet

- Ogl 300 Final PaperDocument7 pagesOgl 300 Final Paperapi-580803791No ratings yet

- Research Paper Leadership PDFDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Leadership PDFhfuwwbvkg100% (1)

- Derue - Et - Al-2011-Trait and Behavioral Theories of Leadership - An Integration and Meta Analytic Test of Their Relative ValidityDocument46 pagesDerue - Et - Al-2011-Trait and Behavioral Theories of Leadership - An Integration and Meta Analytic Test of Their Relative ValidityMy Nguyen Ha QTKD-5K-17No ratings yet

- Assessment of Adjustment, Decision Making Ability in Relation To Personality of AdolescentsDocument9 pagesAssessment of Adjustment, Decision Making Ability in Relation To Personality of AdolescentsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Transformational-Transactional Leadership TheoryDocument34 pagesTransformational-Transactional Leadership TheoryAnthony WilsonNo ratings yet

- Ryan Moore Lit ReviewDocument6 pagesRyan Moore Lit Reviewapi-609524066No ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence and Transformational and Transactional LeadershipDocument14 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Transformational and Transactional LeadershipAnonymous phas7nu3bNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Reynolds & Warfield - Discerning The Differences Between Managers and LeadersDocument5 pages2010 - Reynolds & Warfield - Discerning The Differences Between Managers and LeadersApollo Yap100% (1)

- Development and Preliminary Validation of The Youth Leadership Potential ScaleDocument14 pagesDevelopment and Preliminary Validation of The Youth Leadership Potential ScaleHebo NajiNo ratings yet

- Collete Taylor - Visionary LeadershipDocument19 pagesCollete Taylor - Visionary LeadershipAura IlieNo ratings yet

- أثر إدارة المواهب في الأداء الوظيفي في المنظمات الحكومية في المملكة العربية السعوديةDocument20 pagesأثر إدارة المواهب في الأداء الوظيفي في المنظمات الحكومية في المملكة العربية السعوديةMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- Agri Food SupplychainDocument39 pagesAgri Food SupplychainMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Human Resource ManagementDocument7 pagesAn Introduction To Human Resource ManagementMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Covid-19 On Tourism SustainabilityDocument7 pagesThe Impact of Covid-19 On Tourism SustainabilityMohammad Al-arrabi Aldhidi100% (1)

- Sustainability 12 00263 v2Document38 pagesSustainability 12 00263 v2Mohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- Impact of COVID-19: Research Note On Tourism and Hospitality Sectors in The Epicenter of Wuhan and Hubei Provinc..Document16 pagesImpact of COVID-19: Research Note On Tourism and Hospitality Sectors in The Epicenter of Wuhan and Hubei Provinc..Mohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- K Reiner 2020Document15 pagesK Reiner 2020Mohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- How To Build A Sustainable MICE Environment Based On Social Identity TheoryDocument15 pagesHow To Build A Sustainable MICE Environment Based On Social Identity TheoryMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Hotel CSR For Strategic Philanthropy On Booking Behavior and Hotel Performance During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument37 pagesThe Impact of Hotel CSR For Strategic Philanthropy On Booking Behavior and Hotel Performance During The COVID-19 PandemicMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- Ffects of Green Restaurant Attributes OnDocument20 pagesFfects of Green Restaurant Attributes OnMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet

- Impact of Employee Job Attitudes On Ecological Green Behavior in Hospitality SectorDocument14 pagesImpact of Employee Job Attitudes On Ecological Green Behavior in Hospitality SectorMohammad Al-arrabi AldhidiNo ratings yet