Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oil Conti N:a Vs Turbo Charts

Uploaded by

PhilOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oil Conti N:a Vs Turbo Charts

Uploaded by

PhilCopyright:

Available Formats

The Oil Report

February 2019

Oil the News that’s Fit to Print!

We’ll be at Oshkosh this year! Find us at booth 4064 to

Do I Need to Worry? stock up on discounted bulk samples, ask questions, look

By Amanda Callahan at your report, and meet our analysts.

“Do I need to worry?” is a common question we get, and one there’s not one easy answer for. We’ve had

people pull the bearings out of a Corvette when lead was only a few ppm above average and we actually said

in the report, “You don’t need to do anything about this yet.” (For the record, that guy called us and said his

bearings looked fine and was kind of honked off about it.) We’ve had people with metals that are high all

along, but not changing, and it never turns into a problem. And we’ve had people not pursue what appeared

to be a problem, and regret it in the end. That’s especially problematic when the engine is in an airplane! So

how do we decide what’s a problem and what’s not? It would be great if there was a magic number, but

there’s not. We assess each engine individually, mainly focusing on these things:

1. How your sample compares to your trends

2. How your sample compares to average

3. The balance of metals to each other

4. What kind of cylinders you have installed

5. How your twin engines are wearing in relation to one another

6. Oil type

7. Corrosion

Trends

Figure 1: Continental O-300-C If you have them, trends are the number one most

helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s

health. It takes about three samples to get a good

trend going (though we can often tell if something is

amiss earlier than that). All engines are different, as

are their operators and the amount/frequency/type

of use they receive, and where they are in the coun-

try. As such, it’s very helpful to sample a few oil

changes in a row, at least at first, and have a baseline

established for your specific engine.

Consistency counts for a lot. If your engine is wearing

a lot but it’s doing so steadily, it’s entirely possible

that the metal isn’t a problem. Problems tend to get

worse over time – not remain stagnant. Figure 1 is a

good example where aluminum (a piston metal) read

Elevated metals may be okay if they’re steady.

©Copyright Blackstone Laboratories Inc., 2019 1

consistently high in this Continental O-300. The owner wasn’t having any problems, and our recommendation

was to just watch aluminum as time goes on.

But on the other hand, look at Figure 2. Copper (from brass/bronze parts like bushings and bearings) wasn’t

unusually high compared to averages for this IO-550-N27, but it was higher than before, and as such we

flagged it as something to monitor

going forward.

Figure 2: Continental IO-550-N27

Universal averages

Of course, when you first start sam-

pling, you don’t have trends to rely

on. So our second line of defense,

when we’re looking at your num-

bers, is universal averages.

We have averages established for

most of the engines out there,

though we’re always adding to our

database. When you do your first

sample, we’ll compare your metals

to averages for your specific engine.

It’s very helpful for us to know what

kind of engine you have. Take a look

The increase in copper is worth watching, even if the level isn’t high.

Figure 3: Lycoming IO-360-A1A at Figure 3, which shows average wear levels for a Lycoming IO-360-A1A

and Continental TSIO-520-R9B and a Continental TSIO-520-R9B. The big, turbo-charged Continental

makes a lot more metal than the Lycoming does. If we don’t know what

kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to

the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still

often tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences

between your engine and averages are harder to see.

Balance of metals

We also look at the balance of metals relative to each other. In Figure 4,

chrome read a bit out of balance relative to the aluminum and iron

readings. Chrome should be about 20% of iron, but instead it’s closer to

50%. That suggests the piston rings might be wearing a bit more than

they should be. Or, maybe that metal is related to having chromed cylin-

ders on board, which brings us to our next point…

Cylinder metallurgy

Different engines produce differ- Most aircraft engines come with steel cylinders from the factory, and as

ent wear patterns. such, most of the samples in our average files are based on having steel

cylinders on board. If your cylinders have been swapped for chromed or

nickel cylinders, you can expect those metals to read high. See figure 5, for example, which shows the wear

trends from a Lycoming O-320-H2AD with nickel cylinders on the left side of the average column and one with

chromed cylinders on the right side. Since replacement cylinders can affect wear trends, it’s always helpful to

©Copyright Blackstone Laboratories Inc., 2019 2

Figure 4: Continental TSIO-520 have as much information about the brand/type of cyl-

inders you have installed.

Twin engine comparisons

Twin engines of the same age that see the same type of

operation should wear similarly, and as such we always

compare left and right (or front and rear) engines if we

have the opportunity. Figure 6 shows left and right en-

gine samples from a Beechcraft Baron. The left engine is

wearing very well for the type, but the additional metal

in the right engine’s report suggests something might

be amiss – perhaps at steel parts and/or the exhaust

valve guides, though cylinder-area metals are elevated

as well.

Oil types

Aeroshell 15W/50 oil tends to cause high copper read-

ings in Lycoming engines. The copper isn’t poor wear

from brass/bronze parts, but rather it’s a chemical reac-

tion that happens between the oil and a coating applied

A metal reading out of balance relative to the to the engine parts in the nitriding process. The copper

others (chrome here) can indicate poor wear. itself is harmless, but because it can mimic brass/

Figure 5: Lycoming O-320-H2AD

NICKEL CYLINDERS CHROMED CYLINDERS

The universal averages are based on having steel cylinders. These two engines have different wear pat-

terns because of their non-factory cylinders.

©Copyright Blackstone Laboratories Inc., 2019 3

Figure 6: Twin Continental IO-470 engines

bronze wear in a used oil analy-

LEFT ENGINE RIGHT ENGINE sis, it’s important to know the

brand of oil you’re using to rule

out actual brass/bronze wear.

Figure 7 shows the high copper

trend in a Lycoming IO-360-A1A

using Aeroshell 15W/50. In the

most recent report, we decided

to stop marking copper in bold,

given its steadiness and the like-

lihood that it’s just a chemical

reaction in this case.

Corrosion

Because of their open breather

tubes, aircraft engines are more

susceptible to corrosion than

other types of engines are. Our

general rule of thumb is anytime

an engine sees fewer than five

hours of use in a month, it’s in-

active enough to possibly allow

Different wear patterns between twin engines can indicate trouble. for some corrosion to settle in.

Corrosion typically shows in our

reports as high aluminum and

Figure 7: Lycoming IO-360-A1A iron. Look at Figure 8. Frequency

and amount of use dropped sud-

denly for this TSIO-520-NB from

July 2017 to April 2018, and alu-

minum and iron increased at

about the same time, so corro-

sion is the primary suspect in

this case. You might note that

iron isn’t much higher than be-

fore, though because the inter-

val was shorter, the rate per-

hour has increased significantly.

How much metal is too

much?

So how much metal is too

much? In truth that number is

different for every engine. You

already know that we take a lot

of things into account in trying

Copper is high in this engine because of a harmless chemical reac-

tion with the oil.

©Copyright Blackstone Laboratories Inc., 2019 4

Figure 8: Continental TSIO-520-NB

Corrosion may account for the high aluminum and iron readings in the most recent sample.

to answer that question. We’ll call you to get more information if we’re not sure. Usually, we’ll suggest giving

it an oil change or two to see how trends shake out, and as always we suggest checking the oil filter or screen

for metal, as anything large enough to be picked up by the filter or screen isn’t something that will show up

in our testing. If something is seriously out of line we can usually tell, even if we don’t know your engine type

or how you use it.

We will say this, though: it’s pretty rare for a major mechanical problem to happen unexpectedly overnight.

Most engines will give at least some warning before things go south, and that’s why you do analysis. Follow

the trends to see what’s normal for your engine, and when deviations occur, you’re informed enough to

make a good decision.

©Copyright Blackstone Laboratories Inc., 2019 5

Report of The Month

This Austro AE300 diesel engine saw a dramatic spike in lead in December. Can you guess what happened?

To learn more about where the elements are from, click here.

The follow-up samples.

Most piston aircraft engines run 100LL and fuel blow-by causes lead to read at several hundred (or thousand)

ppm. But Jet A doesn’t have any lead in it, so lead should read very low in this engine’s report. Upon seeing

this high lead reading, we cautioned the owner that some 100LL may have been used. He immediately

grounded the aircraft. Before draining the fuel and flushing the fuel system, he took samples from both the

engine oil and the fuel tanks to determine the extent of lingering contamination. Both of those samples

came back without any lead whatsoever, which led us to consider another alternative: sample contamina-

tion. As it turns out, his sample was contaminated by his mechanic before it was sent. This report stands as a

good reminder to track the trends before proceeding with costly repairs, and to always make sure you get a

clean sample.

©Copyright Blackstone Laboratories Inc., 2019 6

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Continental Engine CareDocument74 pagesContinental Engine CareFran Garita75% (4)

- sr22t Engine OperationsDocument102 pagessr22t Engine OperationsPhilNo ratings yet

- Portable Mini Wooden Lathe - Project ProposalDocument3 pagesPortable Mini Wooden Lathe - Project ProposalArsalan Ahmed100% (1)

- Metric Edition of ANSI/AGMA 6101-E08.: ISBN: 978-1-64353-034-5 Pages: 63Document1 pageMetric Edition of ANSI/AGMA 6101-E08.: ISBN: 978-1-64353-034-5 Pages: 63gioNo ratings yet

- B737 Hydraulics QsDocument2 pagesB737 Hydraulics QsPhil0% (1)

- B737 Manouvers 2Document4 pagesB737 Manouvers 2PhilNo ratings yet

- B737 Electrical NotesDocument1 pageB737 Electrical NotesPhilNo ratings yet

- B737 Good To Know LimitationsDocument4 pagesB737 Good To Know LimitationsPhilNo ratings yet

- B737 NG Systems QuestionsDocument3 pagesB737 NG Systems QuestionsPhilNo ratings yet

- B737 Limitations USDocument1 pageB737 Limitations USPhilNo ratings yet

- B737 Non Normal ManouverDocument1 pageB737 Non Normal ManouverPhilNo ratings yet

- 737 Immediate Action Items (RED QRC)Document2 pages737 Immediate Action Items (RED QRC)PhilNo ratings yet

- 737 Bleed Air/Temp/Pressurization System NotesDocument2 pages737 Bleed Air/Temp/Pressurization System NotesPhil100% (1)

- BMW EGR RecallDocument7 pagesBMW EGR RecallPhilNo ratings yet

- B737 Checked LimitationsDocument4 pagesB737 Checked LimitationsPhilNo ratings yet

- An Airline Pilot's Guide To The Single-Pilot Instrument RatingDocument2 pagesAn Airline Pilot's Guide To The Single-Pilot Instrument RatingPhilNo ratings yet

- B737 NG Program - Jan 2015Document1 pageB737 NG Program - Jan 2015PhilNo ratings yet

- An Airline Pilot's Guide To The Single-Pilot Instrument RatingDocument2 pagesAn Airline Pilot's Guide To The Single-Pilot Instrument RatingPhilNo ratings yet

- LONG RANGE Radar/Laser Detector R1: User's ManualDocument12 pagesLONG RANGE Radar/Laser Detector R1: User's ManualPhilNo ratings yet

- Cirrus sr22 g6 Turbo Vs Cessna TTXDocument12 pagesCirrus sr22 g6 Turbo Vs Cessna TTXPhilNo ratings yet

- Twin and Turbine MagazineDocument36 pagesTwin and Turbine MagazinePhil100% (1)

- Type Acceptance Report: Cirrus SR20, SR22 and SR22TDocument17 pagesType Acceptance Report: Cirrus SR20, SR22 and SR22TPhilNo ratings yet

- Cirrus SR20, SR22 and SR22T: Owners' & Pilots' GuideDocument23 pagesCirrus SR20, SR22 and SR22T: Owners' & Pilots' GuidePhilNo ratings yet

- SR22 Checklist PDFDocument45 pagesSR22 Checklist PDFPhilNo ratings yet

- Check List CirrusDocument6 pagesCheck List CirrusValentim Santos100% (1)

- Cirrus SR22 G2 GTS Specifications and Performance PDFDocument3 pagesCirrus SR22 G2 GTS Specifications and Performance PDFAldoNo ratings yet

- 2019 SR22 United States PricelistDocument4 pages2019 SR22 United States PricelistPhilNo ratings yet

- Cirrus SR22T G5 POHDocument506 pagesCirrus SR22T G5 POHPhil50% (2)

- Cirrus sr22 g6 Turbo Vs Cessna TTXDocument12 pagesCirrus sr22 g6 Turbo Vs Cessna TTXPhilNo ratings yet

- Cirrus SR22 POHDocument480 pagesCirrus SR22 POHPhilNo ratings yet

- Cirrus SR Perspective Cockpit Reference GuideDocument120 pagesCirrus SR Perspective Cockpit Reference GuidePhilNo ratings yet

- Welding Quiz 1Document2 pagesWelding Quiz 1Thanga PandiNo ratings yet

- bs1452 Grade 250Document2 pagesbs1452 Grade 250Syed Shoaib RazaNo ratings yet

- UNit 3 Part A RevisedDocument76 pagesUNit 3 Part A Revisedraymon sharmaNo ratings yet

- Welding ConsumablesDocument79 pagesWelding Consumablesazam RazzaqNo ratings yet

- Sae Ams 5555e-2013Document5 pagesSae Ams 5555e-2013Mehdi MokhtariNo ratings yet

- QES PEVC-ENG237 - Checklist For PSS Fencing DetailsDocument2 pagesQES PEVC-ENG237 - Checklist For PSS Fencing DetailsRupesh Khandekar100% (1)

- EMT Conduit PDFDocument2 pagesEMT Conduit PDFbluesierNo ratings yet

- Marking ToolsDocument14 pagesMarking ToolsFabian NdegeNo ratings yet

- Machine Data Sheet: Model G9729 Combo Lathe/MillDocument3 pagesMachine Data Sheet: Model G9729 Combo Lathe/MillJIMJEONo ratings yet

- ASTM A536 Ductile Iron Castings Tensile RequirementsDocument1 pageASTM A536 Ductile Iron Castings Tensile RequirementsKhin Aung Shwe67% (3)

- Durg Factories ListDocument56 pagesDurg Factories ListManan ShahNo ratings yet

- Microstructures of Iron-Carbon Alloys: Fine Pearlite 3000XDocument9 pagesMicrostructures of Iron-Carbon Alloys: Fine Pearlite 3000XVaishu 07No ratings yet

- Mp63i40 ...Document2 pagesMp63i40 ...Ckaal74100% (1)

- Supranox Rs 309L: MMA Electrodes Stainless and Heat Resistant SteelsDocument1 pageSupranox Rs 309L: MMA Electrodes Stainless and Heat Resistant SteelsbrunizzaNo ratings yet

- Bharat Wagon ProjectDocument35 pagesBharat Wagon Projectsuman2567No ratings yet

- CorimpexDocument38 pagesCorimpexmahotkatNo ratings yet

- Please Visit Us at C116/8.1 From 16-21.09.2013 at Schweissen & Schneiden 2013Document2 pagesPlease Visit Us at C116/8.1 From 16-21.09.2013 at Schweissen & Schneiden 2013narendraNo ratings yet

- Hexalobular (6 Lobe) Socket Pan Head Thread Forming Screws Type C, Metric ThreadDocument3 pagesHexalobular (6 Lobe) Socket Pan Head Thread Forming Screws Type C, Metric ThreadRodrigo AugustoNo ratings yet

- Copperwireobjectsfrom Jahundaand Little Mapelatechnologyvaluesystemsandnetworksin Iron Agesouthern AfricaDocument20 pagesCopperwireobjectsfrom Jahundaand Little Mapelatechnologyvaluesystemsandnetworksin Iron Agesouthern AfricaSalumu Mwalimu MkwayuNo ratings yet

- High-Strength Carbon-Manganese Steel of Structural Quality: Standard Specification ForDocument3 pagesHigh-Strength Carbon-Manganese Steel of Structural Quality: Standard Specification ForSama UmateNo ratings yet

- DPX 800MPA M B: Recommended GM Steel Reparability MatrixDocument2 pagesDPX 800MPA M B: Recommended GM Steel Reparability MatrixSilverio AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Sumitec CatalogDocument90 pagesSumitec CatalogIfan JSENo ratings yet

- Top 6 Hydrogen Cracking - Cswip 3.1 Course Questions and AnswersDocument3 pagesTop 6 Hydrogen Cracking - Cswip 3.1 Course Questions and AnswersJlkKumarNo ratings yet

- High Quality Products For Welding and CladdingDocument25 pagesHigh Quality Products For Welding and Claddingsanketpavi21100% (1)

- Is 1865 1991Document16 pagesIs 1865 1991kumarkk1969No ratings yet

- Workshop ManualDocument60 pagesWorkshop ManualRishu pandey100% (1)

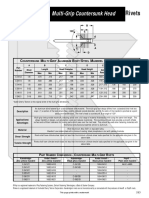

- Rivets Multi Grip CountersunkDocument1 pageRivets Multi Grip CountersunkIsrael OluwagbemiNo ratings yet

- PRC-2003G Heat Treating Nickel AlloysDocument9 pagesPRC-2003G Heat Treating Nickel AlloysHenryNo ratings yet