Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Philippine Revolution: Main Article

Uploaded by

Jin Badon0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views2 pagesOriginal Title

fil am

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views2 pagesPhilippine Revolution: Main Article

Uploaded by

Jin BadonCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Philippine Revolution[edit]

Main article: Philippine Revolution

Andrés Bonifacio was a warehouseman and clerk from Manila. On July 7, 1892, he

established the Katipunan—a revolutionary organization formed to gain independence

from Spanish colonial rule by armed revolt. In August 1896, the Katipunan was

discovered by the Spanish authorities and thus launched its revolution. Fighters

in Cavite province won early victories. One of the most influential and popular leaders

from Cavite was Emilio Aguinaldo, mayor of Cavite El Viejo (modern-day Kawit), who

gained control of much of the eastern portion of Cavite province. Eventually, Aguinaldo

and his faction gained control of the leadership of the Philippine revolution. After

Aguinaldo was elected president of a revolutionary government superseding the

Katipunan at the Tejeros Convention on March 22, 1897, his government had

Bonifacio executed for treason after a show trial on May 10, 1897.[34]

Aguinaldo's exile and return[edit]

Main article: Hong Kong Junta

By late 1897, after a succession of defeats for the revolutionary forces, the Spanish had

regained control over most of the Philippine territory the rebels had taken. Aguinaldo and

Spanish Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera entered into armistice negotiations

while Spanish forces surrounded Aguinaldo's hideout and base in Biak-na-

Bato in Bulacan province, and Aguinaldo reorganized his "Republic of the Philippines" in

the meantime. On December 14, 1897, an agreement was reached in which the Spanish

colonial government would pay Aguinaldo $MXN800,000[a] in Manila—in three

installments if Aguinaldo would go into exile outside of the Philippines.[36][37]

Upon receiving the first of the installments, Aguinaldo and 25 of his closest associates

left their headquarters at Biak-na-Bato and made their way to Hong Kong, according to

the terms of the agreement. Before his departure, Aguinaldo denounced the Philippine

Revolution, exhorted Filipino rebel combatants to disarm, and declared those who

continued hostilities and waging war to be bandits. [38] Despite Aguinaldo's denunciation,

some of the revolutionaries continued their armed revolt against the Spanish colonial

government.[39][40][41][42] According to Aguinaldo, the Spanish never paid the second and

third installments of the agreed-upon sum.[43]

On April 22, 1898, while in exile, Aguinaldo had a private meeting in Singapore with

United States Consul E. Spencer Pratt, after which he decided to again take up the

mantle of leadership in the Philippine Revolution.[44] According to Aguinaldo, Pratt had

communicated with Commodore George Dewey (commander of the Asiatic Squadron of

the United States Navy) by telegram, and passed assurances from Dewey to Aguinaldo

that the United States would recognize the independence of the Philippines under the

protection of the United States Navy. Pratt reportedly stated that there was no necessity

for entering into a formal written agreement because the word of the Admiral and of the

United States Consul were equivalent to the official word of the United States

government.[45] With these assurances, Aguinaldo agreed to return to the Philippines.

Pratt later contested Aguinaldo's account of these events, and denied any "dealings of a

political character" with the leader.[46] Admiral Dewey also refuted Aguinaldo's account,

stating that he had promised nothing regarding the future:

From my observation of Aguinaldo and his advisers I decided that it would

be unwise to co-operate with him or his adherents in an official manner. ...

In short, my policy was to avoid any entangling alliance with the

insurgents, while I appreciated that, pending the arrival of our troops, they

might be of service.[41]

Filipino historian Teodoro Agoncillo writes of "American apostasy", saying that it was the

Americans who first approached Aguinaldo in Hong Kong and Singapore to persuade

him to cooperate with Dewey in wresting power from the Spanish. Conceding that Dewey

may not have promised Aguinaldo American recognition and Philippine independence

(Dewey had no authority to make such promises), he writes that Dewey and Aguinaldo

had an informal alliance to fight a common enemy, that Dewey breached that alliance by

making secret arrangements for a Spanish surrender to American forces, and that he

treated Aguinaldo badly after the surrender was secured. Agoncillo concludes that the

American attitude towards Aguinaldo "... showed that they came to the Philippines not as

a friend, but as an enemy masking as a friend." [47]

You might also like

- History of The Philippines (1898-1946) - WikipediaDocument211 pagesHistory of The Philippines (1898-1946) - WikipediaRacquel DarawayNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldo - Hero or VillainDocument15 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo - Hero or VillainGerard JuntillaNo ratings yet

- The Revolution, Second PhaseDocument4 pagesThe Revolution, Second PhasePercy Samaniego50% (6)

- Declaration of Independence and Revolutionary Government: First Philippine RepublicDocument3 pagesDeclaration of Independence and Revolutionary Government: First Philippine RepublicZamhyrre Perral - ABE FairviewNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldo's Memoirs and Revolutionary CareerDocument26 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo's Memoirs and Revolutionary CareerGeo StellarNo ratings yet

- Historical Context Behind Declaration of PH IndependenceDocument3 pagesHistorical Context Behind Declaration of PH IndependenceJericho Perez100% (1)

- Mga Gunita NG - HimagsikanDocument26 pagesMga Gunita NG - HimagsikanJULIUS L. LEVEN65% (55)

- Lesson 6.0 The Act of Proclamation of Independence of The Filipino PeopleDocument13 pagesLesson 6.0 The Act of Proclamation of Independence of The Filipino PeopleQuinnie CervantesNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Philippine IndependenceDocument2 pagesDeclaration of Philippine IndependenceKirigaya KazutoNo ratings yet

- Philippine-American War Module 5Document5 pagesPhilippine-American War Module 5Threcia MiralNo ratings yet

- Philippine Revolution Second Phase SummaryDocument3 pagesPhilippine Revolution Second Phase SummaryRio AwitinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 17Document50 pagesChapter 12 17GrandpaGyu InSpiRiTNo ratings yet

- Philippine Revolution: MilitaryDocument10 pagesPhilippine Revolution: MilitaryQueensen Mera CantonjosNo ratings yet

- THE Struggle Continues: Reporters: Belaro, Hanielyn B. Cagang, Hillary Jane C. Bsa 1 - ADocument10 pagesTHE Struggle Continues: Reporters: Belaro, Hanielyn B. Cagang, Hillary Jane C. Bsa 1 - ANirvana GolesNo ratings yet

- HeroesDocument3 pagesHeroesSpongie BobNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldomgagunita NG HimagsikanDocument8 pagesEmilio Aguinaldomgagunita NG HimagsikanKent LasicNo ratings yet

- Act of Philippine Independence DeclarationDocument36 pagesAct of Philippine Independence DeclarationDennis RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Chapter X - Philippine Revolution Under AguinaldoDocument4 pagesChapter X - Philippine Revolution Under AguinaldoJames Roi Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Frago - Synchronous 9Document3 pagesFrago - Synchronous 9Justin Johanna FragoNo ratings yet

- Spain United States Philippines Tagalog Manila August Adjacent Cavite KatipunanDocument2 pagesSpain United States Philippines Tagalog Manila August Adjacent Cavite KatipunanKristine CafeNo ratings yet

- Dictatorial and Rebolutionary Government of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesDictatorial and Rebolutionary Government of The PhilippinesSky LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldo Y Famy: Overview BackgroundDocument5 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo Y Famy: Overview BackgroundRodrick Sonajo RamosNo ratings yet

- Lesson2 PHHDocument26 pagesLesson2 PHHAra Mae AlcoberNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6.0 The Act of Proclamation of Independence of The Filipino PeopleDocument10 pagesLesson 6.0 The Act of Proclamation of Independence of The Filipino PeopleQuinnie CervantesNo ratings yet

- Tejeros ConventionDocument6 pagesTejeros ConventionMary Mhajoy A. MacayanNo ratings yet

- Critical analysis of key Philippine independence documentsDocument2 pagesCritical analysis of key Philippine independence documentsSHAINA ANNE BUENAVIDESNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldo: First President of the Philippine RepublicDocument20 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo: First President of the Philippine RepublicRechelleNo ratings yet

- Emilio AguinaldoDocument4 pagesEmilio AguinaldoHannah GrepoNo ratings yet

- The Struggle ContinuesDocument5 pagesThe Struggle ContinuesAbegail Bagaan0% (1)

- Spanish Cavite Offensive and Battle of Perez DasmariñasDocument4 pagesSpanish Cavite Offensive and Battle of Perez Dasmariñasalondra gayonNo ratings yet

- The Act of Proclamation of Independence of The People: (Acta de La Proclamacion de La Inedependencia Del Pueblo Filipino)Document18 pagesThe Act of Proclamation of Independence of The People: (Acta de La Proclamacion de La Inedependencia Del Pueblo Filipino)Nerish PlazaNo ratings yet

- The RevolutionDocument19 pagesThe RevolutionJerica100% (1)

- Emilio Aguinaldo: First President of the Philippine RepublicDocument14 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo: First President of the Philippine RepublicCatherine AmicanNo ratings yet

- Emilio AguinaldoDocument6 pagesEmilio AguinaldoanayNo ratings yet

- Emilio AguinaldoDocument2 pagesEmilio AguinaldoEhl Viña LptNo ratings yet

- Philippine Revolution MemoirsDocument24 pagesPhilippine Revolution MemoirsDawn Juliana AranNo ratings yet

- Philippine Under American RegimeDocument30 pagesPhilippine Under American RegimeDonn MoralesNo ratings yet

- The 2nd Phase of The Philippine RevolutionDocument4 pagesThe 2nd Phase of The Philippine RevolutionGusty Ong VañoNo ratings yet

- Week 13 Soc SciDocument5 pagesWeek 13 Soc SciIsrael Bonite - gscNo ratings yet

- Emilio F. AguinaldoDocument3 pagesEmilio F. AguinaldoAriel DicoreñaNo ratings yet

- American Infiltration in The PhilippinesDocument20 pagesAmerican Infiltration in The PhilippinesMiguel Angelo RositaNo ratings yet

- Battle of Zapote Bridge and Spanish Offensive in 1897Document4 pagesBattle of Zapote Bridge and Spanish Offensive in 1897Zamhyrre Perral - ABE FairviewNo ratings yet

- Philippine RevolutionDocument25 pagesPhilippine RevolutionLinas KondratasNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldo: Hero or GangsterDocument11 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo: Hero or GangsterLiway Generoso100% (1)

- Fray Juan de Plasencia: Juan de Plasencia (Spanish: Juan de Plasencia) Was A Spanish Friar of Thefranciscan OrderDocument6 pagesFray Juan de Plasencia: Juan de Plasencia (Spanish: Juan de Plasencia) Was A Spanish Friar of Thefranciscan Orderpcjohn computershopNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldo y FamyDocument7 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo y FamyHoward ReyneraNo ratings yet

- Readings in Philippine History: Emilio Aguinaldo: Hero or Gangster?Document12 pagesReadings in Philippine History: Emilio Aguinaldo: Hero or Gangster?renz pepa100% (1)

- The Coming of United StatesDocument14 pagesThe Coming of United Statesmaricel cuisonNo ratings yet

- Mga Gunita NG HimagsikanDocument7 pagesMga Gunita NG HimagsikanCatherine Mae MacailaoNo ratings yet

- American Era: 1935 Philippine Presidential ElectionDocument3 pagesAmerican Era: 1935 Philippine Presidential ElectionZamhyrre Perral - ABE FairviewNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 11 SummaryDocument6 pagesCHAPTER 11 SummaryDenzz QuintalNo ratings yet

- Work SheetDocument10 pagesWork Sheetwatermelon sugarNo ratings yet

- Emilio F. Aguinaldo: First President of The Philippines (1897-1901)Document13 pagesEmilio F. Aguinaldo: First President of The Philippines (1897-1901)danieNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 - Declaration of Phil. Ind by Rianzarrez BautistaDocument8 pagesLesson 6 - Declaration of Phil. Ind by Rianzarrez BautistaJanna Grace Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- AbassDocument15 pagesAbassNeil PagadNo ratings yet

- HistorytudyidyDocument28 pagesHistorytudyidyKapid Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Group 3Document11 pagesGroup 3desiree viernesNo ratings yet

- RIPH Act#5Document2 pagesRIPH Act#5Kia GraceNo ratings yet

- War (Modern: Citation NeededDocument1 pageWar (Modern: Citation NeededJin BadonNo ratings yet

- Henry Clark Corbin Adjutant General of The U.S. Army: Main ArticleDocument2 pagesHenry Clark Corbin Adjutant General of The U.S. Army: Main ArticleJin BadonNo ratings yet

- Brian Mcallister Linn. The Philippine War, 1899-1902. Lawrence: University Press of KansasDocument4 pagesBrian Mcallister Linn. The Philippine War, 1899-1902. Lawrence: University Press of KansasJin BadonNo ratings yet

- NICK JOAQUIN Demystifying The Past UnfetDocument18 pagesNICK JOAQUIN Demystifying The Past UnfetDareyn MacedaNo ratings yet

- The Philippines, A Past Revisited - Renato ConstantinoDocument471 pagesThe Philippines, A Past Revisited - Renato ConstantinoIronnelCostales100% (2)

- War Against Stars and StripesDocument39 pagesWar Against Stars and StripesJin BadonNo ratings yet

- IntroDocument1 pageIntroJin BadonNo ratings yet

- Fascinating Facts About the PhilippinesDocument2 pagesFascinating Facts About the PhilippinesAnj HwanNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Case Digest 1 4Document6 pagesCorporation Law Case Digest 1 4Rhythmic CampNo ratings yet

- Gr7musicteachersguide 120613203109 Phpapp02Document42 pagesGr7musicteachersguide 120613203109 Phpapp02Rjvm Net Ca FeNo ratings yet

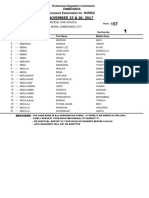

- RA NURSE ZAMBO Nov2017 PDFDocument53 pagesRA NURSE ZAMBO Nov2017 PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- PSU Lingayen OJT certificatesDocument7 pagesPSU Lingayen OJT certificatesAntonio de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Prof. Pedrito A. SalvadorDocument7 pagesProf. Pedrito A. SalvadorPed Salvador100% (2)

- Republic of the Philippines Religion and Belief Systems Table of SpecificationDocument16 pagesRepublic of the Philippines Religion and Belief Systems Table of SpecificationRaquel Domingo100% (1)

- FIlipino National ArtistDocument10 pagesFIlipino National ArtistJasper MabiniNo ratings yet

- Locsin, Noble Chino Cristiano (A Novelized Biography of Sin Loc)Document28 pagesLocsin, Noble Chino Cristiano (A Novelized Biography of Sin Loc)Seminario LipaNo ratings yet

- Political Psychology in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesPolitical Psychology in The PhilippinesArielle LibotanNo ratings yet

- GECLIF-Module 3 - Annotation of Morga S Sucesos de Las Islas FilipinasDocument37 pagesGECLIF-Module 3 - Annotation of Morga S Sucesos de Las Islas Filipinasching100% (1)

- Have You Ever Wondered How The Philippine Art Developed?Document15 pagesHave You Ever Wondered How The Philippine Art Developed?Ryan TusalimNo ratings yet

- Quezon - ProvDocument4 pagesQuezon - ProvireneNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights Concepts and CasesDocument2 pagesBill of Rights Concepts and CasesArvin ArenasNo ratings yet

- The Basis For Civil Society in The Philippines Is Provided by The Filipino Concepts of PakikipagkapwaDocument4 pagesThe Basis For Civil Society in The Philippines Is Provided by The Filipino Concepts of PakikipagkapwaMaria SalveNo ratings yet

- Nluc Foundation 2017 For FINAL PDFDocument36 pagesNluc Foundation 2017 For FINAL PDFLester Eslava OrpillaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Lesson 1Document26 pagesModule 1 Lesson 1E-dlord M-alabananNo ratings yet

- Labor Law Case on Temporary Suspension of Recruitment of Filipino Domestic Helpers for Hong KongDocument278 pagesLabor Law Case on Temporary Suspension of Recruitment of Filipino Domestic Helpers for Hong KongLDNo ratings yet

- Philippine 21st Century Literature Regions and AuthorsDocument22 pagesPhilippine 21st Century Literature Regions and AuthorsOtencianoNo ratings yet

- Historical Development of The Philippine Educational SystemDocument12 pagesHistorical Development of The Philippine Educational SystemRiza Pearl LlonaNo ratings yet

- ReadingDocument22 pagesReadingMichelle Awa-aoNo ratings yet

- Cultural Communities and Physical Fitness Standards of Fule Almede Elementary SchoolDocument6 pagesCultural Communities and Physical Fitness Standards of Fule Almede Elementary SchoolJocelynNo ratings yet

- Module 9: Cavite MutinyDocument5 pagesModule 9: Cavite Mutinyjanela mae d. nabosNo ratings yet

- Athlete Record TemplateDocument12 pagesAthlete Record TemplateJessel PalermoNo ratings yet

- Pluma: Sumusulat, NagmumulatDocument9 pagesPluma: Sumusulat, NagmumulatmkNo ratings yet

- The Kundiman - Chapter 1Document19 pagesThe Kundiman - Chapter 1elliotNo ratings yet

- Lesson3-Self As FilipinoDocument23 pagesLesson3-Self As FilipinoNino Joycelee TuboNo ratings yet

- 4 Arts Promotion and PreservationDocument32 pages4 Arts Promotion and PreservationLalaine FuntalbaNo ratings yet

- Notes in LanguageDocument2 pagesNotes in LanguageJR MendezNo ratings yet

- South CotabatoDocument2 pagesSouth CotabatoSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet