Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Verne Reynolds's Etude No. 6 From 48 Etudes: by William Eisenberg

Uploaded by

Gaspare BalconiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Verne Reynolds's Etude No. 6 From 48 Etudes: by William Eisenberg

Uploaded by

Gaspare BalconiCopyright:

Available Formats

Verne Reynolds’s Etude No.

6

from 48 Etudes

by William Eisenberg

V

erne Reynolds published his 48 Etudes for French Horn in guiding practices, it is difficult to pinpoint the real points of

1961. These etudes, like those of Chopin, Scriabin, and arrival, on the small scale and the large, and the piece can end

Rachmaninoff, are both technical studies and works of up sounding like a long run-on sentence. Therefore, one must

art – works with “sufficient musical merit” to deserve perfor- get a handle on the organizational logic that drives the phrase

mance, as Reynolds states in his introduction. Nevertheless, structures and the large-scale form.

the etudes have remained mostly in the practice room and off Verne Reynolds states that this etude is one of his “inter-

the stage. Perhaps the lack of performances and recordings is val studies.” The minor third plays a vital role in the underly-

due to their significant technical difficulty, which overshadows ing harmony and the ends of phrases and sections. Reynolds

their musical worth. Yet, to my mind, these are wonderfully generates different harmonies by combining minor thirds in a

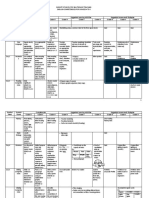

expressive compositions that deserve to be performed. This ar- variety of ways (see Figure 1). Specific set classes1 serve differ-

ticle examines some of the challenges one faces in Etude No. 6, ent functions: [0369], the set-class of the diminished 7th chord

sheds light on its formal and harmonic language, and suggests works as a signature harmony or signpost; [0134] is the collec-

how one might use this knowledge to craft a more compelling tion of the piece’s head motif; and chromatic clusters appear

performance. throughout. These collections, with their distinct intervallic

Verne Reynolds

profiles, mark new sections.

Figure 1

b˙ ™ b˙

Adagio q = 72

& 4 b˙ ™ ˙™

5 ˙ œ#œ œ œn˙ bœ œ œ œnœ œ œ

˙ ˙ ˙ ˙™ Œ œ #œ#œ œ œ œ œ

Horn in F

(not at concert) mp mf mp cresc.

Some combinations of minor thirds

8

nœ œ œ œ nœ#œ ˙ œ

œ œnœ œœ œ œ#œ nœ œ œ w

3

œ Œ

˙™ b ˙ ™ b˙

& #œ#œ nœ#œ

#˙ ™

œ ˙ ˙ m. 1 m. 7 m. 17

& œ œ bœ #œ œ œ œ œ œ

œ #œ œ

œ #œ nœ b œ ™ œ œ #œ

f mp

œœœ œ œ œœ

15

Œ œ #œ #œ #œ #˙ J

n˙ ™

& n˙ œœ œ œ #˙ #œ n˙ [0134] [0369], a fully diminished chord [0358], a minor 7th sonority

œ ˙ mf

f

m. 19 m. 40 m. 54

nœ ™ bœ #œ #œ œ œ #œ œ

œ ˙ Œ œ™ bœj œ

œ œ j œ bœ œ j #œ

nœ œ & #œ #œ œ

22

nœ bœ nœ

œ™ œ bœ ™ #œ

& #œ #œ#œ J nœ œ bœn˙ Œ œ #œ œ

p mf f

œ œ w

[036] (a diminished triad) chromatic hexachord, or [012345] [0347]

b˙ ™ ˙™ œ œ œ ™ #œJ

29

& b˙ ™ ‰

3 3

˙ ˙ ˙™ ˙ ˙ œ nœ #œ œ

#œ œ

The etude is in an ABA’ form, with the overall structure

3

mp mf

nœ #œ #œ nœ nœ nœ 3

34

#œ ‰ nœ nœ nœ

3

‰

3 3

outlining a rise and fall in several ways. The A section begins

Ϫ

& j

#œ nœ

3 3 #œ nœ œ nœ bœ #œ nœ in the middle range of the horn, and stays in this register until

36 n œ b œ nœ m. 28. The highest point appears in the middle of the B section,

bœ œ nœ nœ ‰ #œ œ #œ nœ bœ ‰ #œ œ nœ bœ bœ

3 3 §?

& œ œ bœ #œ nœ nœ nœ bœ œ

3 3

3

f

3

mp 3 3 3

which runs from mm. 29-42. The closing A’ section plummets

to the lower register, and comes to a close after gravitating to

bœ #œ nœ nœ œ

38

nœ nœ bœ

& ≈ nœ bœ bœ œ #œ nœ bœ #œ nœ ≈ œ œ nœ #œ #œ œ œ #œ ‰ ≈ nœ nœ Œ ≈

bœ #œ œ and solidifying the low c [as written, in F]. The etude has a hair-

pin shape dynamically, too – it opens softly, builds throughout

œbœ ‰ ≈

40

bœ bœ bœ bœ œ œ the development, and closes with a pianissimo. Rhythmically,

& bœbœ ‰ ≈bœ œ nœ œ œ nœ œ bœ œ œ nœ# œ œ œ œ œ bœbœ œ bw Œ

n œ # œ bœbœ œ

f mp the opening and closing sections feature only eighth notes and

n˙ ™ longer note values while the development relies almost exclu-

& #˙ ™

b˙ n˙ ™ ˙ #˙

Œ #œ œ œ œ œ œ n˙ ™ b˙

43

n˙

#˙ ™ ‰ j ?

#œ ˙ œ œ œ œ #˙ #˙ ™ mf sively on triplets and sixteenth notes. The B section also accel-

mp

erates the presentation of minor third cells. Like a pot coming

? <b>œ œ œ œ bœ bœ bœ œ nœ nœ & ?œ œ œ j j

51

œ& œ #œ œ™ œ œ™ nœ

nœ ™ J

?œ ?

&œ œ œ bœ œ œ œ œ œ to a boil, the surface becomes muddied as seconds and major

œ

55

thirds emerge forcefully, overshadowing the clearer presenta-

? b˙ n˙ #œ ˙ ˙™ nw œ ˙™ ˙ ˙™ ˙ œ Œ Œ Ó tion of minor thirds in the outer sections. Performers have a

dim. pp choice to make here: they can cut across the grain of some of

the slurs to bring out other intervals or continue to emphasize

the minor thirds, which compose the lines.

An interpreter of this etude faces significant challenges

The opening four-bar motif recurs four times, each at an

from the structure, harmonic logic, and lack of tonality. With-

important structural point (see Figure 2). Each statement main-

out a single key to govern tonic-dominant progressions and

tains the same [0134] sonority and rhythmic profile, but serves

cadential gestures, it is easy to get lost. In a tonal work, tension

a unique role. In the first occurrence, the thirds fold in on each

and release is driven by traditional voice leading – dissonance

other, but the second two-bar grouping doesn’t overlap the

is carefully resolved by step, minor sevenths resolve down-

first. When the motif returns in mm. 12-15, the measures work

ward, leading tones resolve upward, and so on. Without these

upward chromatically, overlapping each other and forming

90 The Horn Call - October 2011

Reynolds’s Etude No. 6

a central axis around b, a minor third below and above. It is eight-measure theme built out of two four-measure phrases.”

also important to note that the shape of each two-bar cell is It “begins with a four-measure presentation, consisting of a

an inversion of the opening gestures. The next occurrence in repeated two-measure basic idea” and ends with a continu-

mm. 29-32, which marks the beginning of the B section, uses ation that “brings closure” (Caplin 1998). In other words, the

the same gesture as the opening, but starts lower, allowing presentation includes the basic idea (a motif or fragment) and

Reynolds to return to the opening pitches when he sequences its restatement, either verbatim or with registral or harmonic

the motif up a perfect fourth, just as he did earlier. The final variations. The continuation typically features an intensifica-

appearance of the motif, from mm. 43-46, marks the start of tion of harmonic rhythm, melodic fragmentation, and a drive

the A’ section. Like the second occurrence, the gesture is in- towards a cadence. As an example, think of the opening horn

bÆÆ

verted, but instead of closing on an expected e , it drops an statement in the first movement of Mozart’s first horn concerto,

#ÆÆ #

octave from the f , and then another octave to f in the next bar. or the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (after the first

These octave leaps signal a change in section and are a sign that two fermatas). Unlike its companion structure, the parallel pe-

the piece is coming to its final phrase. If treated properly, this riod,3 a sentence moves forward with tension and energy – it

change of pattern on the fourth (and final) occurrence has the has, in other words, a “progressive” dynamic.

potential to be a particularly surprising and expressive event. Sentences saturate this etude and are established at the

outset. The basic idea is stated in the first two measures. It in-

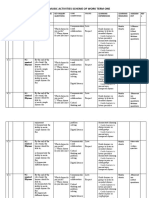

Figure 2

troduces the short-long and long-short rhythmic motifs, which

Fig. 2: Associations among recurrences of the head motif

combine into a [0134] sonority, the same set as the first four

notes of an octatonic scale.4 The dynamic swell of the basic

b˙ ™

(a) mm. 1-4, head motif, [0134] transposed up a P4

idea, with a crescendo and decrescendo, mirrors the shape of the

Horn in F & 45 b˙ ™ ˙ ˙ ˙™ b˙ ˙ ˙™ entire piece. The next two measures transpose the basic idea

up a perfect fourth. While a typical sentence has a continuation

lasting four measures, this one lasts for seven. The extension

(b) mm. 12-15, head motif inverted then transposed up a M2

runs from mm. 6-9 and explores a diminished-seventh sonority

˙™ b˙™

&

#˙ ™ ˙ ˙ b˙ n˙ ˙™ within the context of an octatonic collection. The closing sec-

tion can also be thought of as an expanded sentence. Measure

(c) mm. 29-32, transposed up a P4 in order to return to the opening pitches in (a)

39 recapitulates the basic idea from the opening; a new two-

& b˙ ™ b˙ ™ ˙™

measure motive appears in m. 47, which then repeats down a

˙ ˙ ˙™ ˙ ˙ perfect fourth. As was the case with the opening sentence, this

continuation is also extended. Reynolds closes on an A-C dyad

(d) mm. 43-46, inverted like (b), with varied transpositions expected D#

that mimics the close of the opening four bars, but he lingers on

& #˙ ™

˙ these notes, slowing to a crawl as the piece spends its last eight

#˙

avoided

˙ b˙ ˙™

#˙ ™

˙™ measures on a single [0347] sonority. This realization of the

collection has a more open feel than the opening [0134] gesture:

While the thirds in the opening seem to fold in on each other,

the thirds at the end open outward, widening spatially along

An understanding of the rhythmic structure is also inte-

with the broadening of rhythm.

gral to an effective performance. The opening bars lay out two

Articulating the climax of the etude is also essential to a

motifs that play vital roles in the etude: long–short followed by

compelling performance. The highest note, at a dynamic of

short–long. These twin motifs recur throughout. They accentu- ÆÆ

forte, occurs on the b in m. 36. The etude has been gradually

ate the asymmetry of the 5/4 meter, made plain in the open-

climbing upward to this point, after which the register slowly

ing bars where the motifs are stated with a dotted-half and a

and inexorably descends until the final measures. This climac-

half note. In these measures, the long–short gesture brings an ÆÆ

tic b is structurally significant: it is the midpoint of both the

increase in volume and intensity while the short–long gesture

entire etude and the B section. On the surface, its arrival is

is heard as a relaxation. Reynolds often uses a series of short

marked by a change in m. 38 from triplet rhythms to sixteenth

notes followed by a longer one as a cadential gesture at phrase ÆÆ

notes. At first glance, b appears to be the climax. But a closer

endings. The reverse pattern (long–short) signals an increase in

reading offers several compelling reasons to maintain the in-

tension. In mm. 16-18, for instance, the phrase builds in inten- ÆÆ ÆÆ

tensity through the b until the e at the downbeat of m. 37.

sity, as shorter eighth notes follow the opening slower rhythm,

One reason is the fact that downbeats serve to articulate phrase

then relaxes into the downbeat of m. 18 on the short-long fig-

beginnings and endings as well as new sections. To wit, the

ure. Another example of rhythm intensity occurs in mm. 47-

opening phrase ends on a downbeat whole note in m. 11, the B

48, where eighth notes push the phrase forward and an exact

section closes on a downbeat whole note in m. 42, and the final

recurrence of the original short-long motive brings it to a close.

note begins and ends on a downbeat. Since downbeats tend to

As mentioned earlier, one of the main challenges in this

occupy places of strongest arrival, it makes sense to continue

etude is avoiding a run-on sentence. An understanding of the

to build through the middle of measure 36 until the downbeat

phrase structures is a huge step towards avoiding this pitfall. ÆÆ

of m. 37. Another reason to build the energy to the e is that the

Although this is an atonal composition, Reynolds makes use ÆÆ ÆÆ

b to e gesture of the climax has been carefully foreshadowed.

of one of the most common phrase structures in the Classical Æ

The main points of arrival leading up to the climax are the b

period: the sentence.2 William Caplin defines a sentence as “an

at the end of the opening phrase in m. 11, and the e at the end

The Horn Call - October 2011 91

Reynolds’s Etude No. 6

of the A section in mm. 27-28. Bringing out the gesture in the

ÆÆ ÆÆ

climax from b - e connects these three events.

Breathing is a very familiar issue to horn players. Unlike

orchestral passages, where one might quickly snag an unno-

ticed breath, breathing in this etude is exposed. With this in

mind, breathing and phrasing must always go hand in hand.

There are two types of breath to consider, active and passive.

Active breaths are a part of the musical line and can be thought

of as being “articulated” in much the same way a tongued note

is. For example, the listener should palpably feel the eighth-

note rest in m. 35 – a clear release on the preceding note and

sharp attack on the following will ensure this. Passive breaths,

on the other hand, are actual silences that serve to create space

between sections. Not all passive breaths need be equal, how-

ever. Before beginning the second phrase in m. 12, one might

pause slightly longer than a quarter rest, but an even bigger

space should mark the end of the first main section and the

beginning of the B section at m. 29. The silence before return-

ing to the calm of the A’ section at m. 43 should be longer still

– even a pause of several seconds would not be out of place.

This silence allows the turmoil of the B section to fade away

and prepares the listener for the return to the inversion of the

opening gesture.

In a perfect world, we would never be forced to “catch”

a breath. Since everyone has to breathe eventually, it is im-

portant to make these breaths musical. The length of a breath,

whether it is active or passive, and how to connect the material

on either side of the breath should all be considered. In gen-

eral, breaths can be taken every two bars, and at the notated

rests. Those in parentheses show logical places to put addi-

tional breaths, if necessary. It is especially important to make

these extra breaths musical, as well. For example, if one does

not breath in m. 53, it is easy to emphasize the octave leap from

Æ

c to c, but this is also possible even with a breath: we simply

make sure that the breath is active, and feels like a slight lift

before the low c, rather than a stop and restart.

Much more remains to be explored in this piece. But I

hope that this essay provides insight into the etude’s large-

scale rhythmic, dynamic, and registral shape, as well as the fre-

quent use of sentences, the combinations of minor thirds, and

the interplay of short-long rhythmic motifs. I also hope that it

can serve as a starting point and a guide for performers who

are interested both in building technique and making compel-

ling music: For a careful consideration (or “close reading”) of

structure, articulation, and logic can inform performances of

Reynolds’s other etudes, which contain as much depth and

“musical merit” as this one.

Works Cited

Caplin,William E.. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Func-

tions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.

New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1998.

Forte, Allen. The Structure of Atonal Music. New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1973.

Rahn, John. Basic Atonal Theory. New York: Longman, 1980.

Reynolds,Verne. 48 Etudes for French Horn. New York NY:

G. Schirmer, Inc., 1961.

92 The Horn Call - October 2011

Sure Shot Playing

William Eisenberg is a senior at Oberlin Conservatory, where Personally I was never a “sure shot” horn player. But when

he studies horn with Professor Roland Pandolfi. He has also attended I gradually applied this idea to the whole range, I became a

the Interlochen Summer Arts Camp and the Kent/Blossom Summer “sure shot!” Ironically, I discovered this remarkable principal

Music Festival, where he studied with Richard King. Special thanks about six months before I decided to retire!

to Professor Brian Alegant for his help in preparing this article. “Sure shot” players do not change the texture of the upper

lip. They do it naturally without knowing why. Now “sure

Notes shot” playing can be available to everyone who applies this

1. Set classes are a way of classifying collections of notes. Here, I represent upper lip principal!

set classes as constructs called “prime forms;” all transpositions and inversions The biography of Fred Fox, the most recent IHS Punto Award

of the same collection share the same combination of interval classes, and thus winner, is found on page 59. Fred expounded on this topic at the

belong to the same prime form. For example, a D diminished seventh chord International Horn Symposium.

and an F# diminished seventh chord belong to the prime form [0369]. See the

works cited for several resources on set class theory.

2. The term “sentence” (Satz in German) was coined by Arnold Schoen-

berg (an important theorist as well as an extremely influential composer). See

Caplin’s Classical Form for further discussion.

3. A parallel period features a phrase repeated twice, first with a weaker

cadence and then with a stronger cadence. As an example, think of the first two

phrases of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” from the Ninth Symphony.

4. The octatonic scale alternates whole steps and half steps: C–C#–D#-E-F#,

and so on. This collection is also referred to as a “diminished scale” by many

jazz musician.

Sure Shot Playing (or the ”hanging lip”)

by Fred Fox

I

magine a woodwind player using a medium hard reed. No

matter how high or low he plays, the reed remains medium

hard. It doesn’t change regardless of the register or how

hard he presses on it.

The same should be true for a brass player. Most brass

players make the upper vibrating lip inside the mouthpiece

stiffer as they play in the upper range. This creates another

“moving part” or an extra error-prone possibility. This upper

lip change can be eliminated, thus greatly increasing the ac-

curacy of the player!

Play a middle register note on your instrument. Then play

a note one-third higher, concentrating upon keeping the upper

lip that is in the mouthpiece identical, with no change what-

soever. Yes, the muscles around the mouthpiece will change

but not the vibrating upper lip inside the mouthpiece. That

remains like a reed – not harder or softer but the very same

texture.

You will be surprised to find that you can play those notes

going up and back a third without changing the upper lip ten-

sion inside the mouthpiece. Once you can do this, you can

gradually extend the range in both directions with no change

of the upper lip.

The Horn Call - October 2011 93

You might also like

- Concerto For Two Horns in E-Flat Major Attributed To Joseph Haydn - A New Arrangement For Wind Ensemble by Guan-Lin Yeh PDFDocument188 pagesConcerto For Two Horns in E-Flat Major Attributed To Joseph Haydn - A New Arrangement For Wind Ensemble by Guan-Lin Yeh PDFMcJayJazz0% (1)

- Verdi (Master Musicians Series) - Budden, JulianDocument1,504 pagesVerdi (Master Musicians Series) - Budden, JulianElision0667% (6)

- Figured Bass Haendel PDFDocument107 pagesFigured Bass Haendel PDFrobert100% (3)

- Mastery of the French Horn: Technique and musical expressionFrom EverandMastery of the French Horn: Technique and musical expressionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Law in Action Understanding Canadian LawDocument19 pagesLaw in Action Understanding Canadian LawGloria VelezNo ratings yet

- RCM HarmonyDocument39 pagesRCM HarmonybleufeeNo ratings yet

- Rubric SongwritingDocument2 pagesRubric Songwritingapi-370906687100% (1)

- The Doflein Method: The Violinist's Progress. Development of technique within the first positionFrom EverandThe Doflein Method: The Violinist's Progress. Development of technique within the first positionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Bordogni Low Horn Bootcamp Sample PDFDocument5 pagesBordogni Low Horn Bootcamp Sample PDFGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- BERRY, Walace - Musical Structure and Perfomance PDFDocument128 pagesBERRY, Walace - Musical Structure and Perfomance PDFRose Dália Carlos100% (1)

- Keyboard HarmonyDocument44 pagesKeyboard Harmonyvmartinezvilella100% (3)

- Pianist - April May.2017Document91 pagesPianist - April May.2017Alain Lachaume100% (15)

- King of Denmark PDFDocument14 pagesKing of Denmark PDFJacopoNo ratings yet

- Piano Teachers Guide PDFDocument188 pagesPiano Teachers Guide PDFMichelle Mel86% (7)

- Ravel 5 Miroirs No.1 NoctuellesDocument15 pagesRavel 5 Miroirs No.1 NoctuellesBBIIYAUNo ratings yet

- Lexcerpts - Orchestral Excerpts For Horn v3.11 (US) PDFDocument213 pagesLexcerpts - Orchestral Excerpts For Horn v3.11 (US) PDFpedro ribeirinoNo ratings yet

- Only The Good Die YoungDocument8 pagesOnly The Good Die Youngjon_scribd2372No ratings yet

- Telling True Stories: A Nonfiction Writers Guide From The Nieman FoundationDocument5 pagesTelling True Stories: A Nonfiction Writers Guide From The Nieman FoundationAntoine Delroise100% (1)

- Lifes A Party FontDocument2 pagesLifes A Party FontJilliene IsaacsNo ratings yet

- Sight Reading For Drummers: by Frank DerrickDocument2 pagesSight Reading For Drummers: by Frank DerrickRichard Bulos MontalbanNo ratings yet

- Cm9 UpdatedDocument23 pagesCm9 UpdatedJzaninna Sol BagtasNo ratings yet

- Cu31924021757228 PDFDocument164 pagesCu31924021757228 PDFEsteban Carrasco ZehenderNo ratings yet

- SOJS AdDocument2 pagesSOJS AdGeorgeLouisRamirezNo ratings yet

- Laude: EntenaryDocument12 pagesLaude: EntenaryJohnBaptistNo ratings yet

- F&A Lecture 1Document8 pagesF&A Lecture 1RonaldNo ratings yet

- LP Eng6Document12 pagesLP Eng6Mary Kryss DG SangleNo ratings yet

- English GR 456 1st Quarter MG Bow 1Document24 pagesEnglish GR 456 1st Quarter MG Bow 1api-359551623100% (1)

- Arranging For Strings, Part 1Document6 pagesArranging For Strings, Part 1MassimoDiscepoli100% (1)

- TMM E-Workbook, PT 2 PDFDocument93 pagesTMM E-Workbook, PT 2 PDFKanyin Ojo100% (1)

- Diversidad - 969863 10 11Document2 pagesDiversidad - 969863 10 11Silvia BNo ratings yet

- Espagnole: Allegro VivaceDocument1 pageEspagnole: Allegro VivaceFJRANo ratings yet

- LP The Science of Vocal Pedagogy D Ralph AppelmanDocument12 pagesLP The Science of Vocal Pedagogy D Ralph AppelmanrobertoNo ratings yet

- Table of Specification First Quarter Examination English 10 S.Y. 2017-2018 Subtotal 1 Subtotal 2 Subtotal 3 Total NoDocument3 pagesTable of Specification First Quarter Examination English 10 S.Y. 2017-2018 Subtotal 1 Subtotal 2 Subtotal 3 Total NoSHEILA A. PAGNANAWONNo ratings yet

- Dallin Text 06Document17 pagesDallin Text 06VishnuNo ratings yet

- Arranging For StringsDocument27 pagesArranging For Stringscub moxfNo ratings yet

- Melodia Sight SingingDocument216 pagesMelodia Sight SingingRafael LealNo ratings yet

- Jazz Preparation Pack Chord ProgressionsDocument4 pagesJazz Preparation Pack Chord ProgressionsAllan CifuentesNo ratings yet

- MAPEH Weekly Home Learning PlanDocument5 pagesMAPEH Weekly Home Learning PlanRASHILOUNo ratings yet

- PDF Figured Bass Haendel PDF CompressDocument107 pagesPDF Figured Bass Haendel PDF CompressDesiderio Elielton100% (1)

- IMSLP627502-PMLP2017-Rachmaninov Prelude Op 23 #1Document8 pagesIMSLP627502-PMLP2017-Rachmaninov Prelude Op 23 #1Seba Gonzalez LopezNo ratings yet

- Weekly Plan STD WK 4Document4 pagesWeekly Plan STD WK 4cyberfoxx2007No ratings yet

- Scheme of Work - Std. 2 TERM 1-13-17Document5 pagesScheme of Work - Std. 2 TERM 1-13-17cyberfoxx2007No ratings yet

- Curriculum Map in Mathematics: Phoenix Math For The 21 Century Second Edition Learner Page2-24Document2 pagesCurriculum Map in Mathematics: Phoenix Math For The 21 Century Second Edition Learner Page2-24Ogaban JamilNo ratings yet

- CM9 FinalDocument23 pagesCM9 FinalJzaninna Sol BagtasNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map: English 9 Sy16-17Document31 pagesCurriculum Map: English 9 Sy16-17Jzaninna Sol Bagtas100% (1)

- Bounce Now2 Home Study 1 - 5Document16 pagesBounce Now2 Home Study 1 - 5Control EscolarNo ratings yet

- Lesson - Plan - Discovering - The - Scene (Stratfrod)Document8 pagesLesson - Plan - Discovering - The - Scene (Stratfrod)RunhartNo ratings yet

- JazzBootCampVol1 PDFDocument41 pagesJazzBootCampVol1 PDFCarlosAndrésPeñaRuiz100% (3)

- Rachmaninoff C Sharp Prelude Booklet WebDocument13 pagesRachmaninoff C Sharp Prelude Booklet WebdeadlymajestyNo ratings yet

- PP1 MUSIC ACTIVITIES SCHEME OF WORKDocument6 pagesPP1 MUSIC ACTIVITIES SCHEME OF WORKWan TechNo ratings yet

- Neoclassic and Romantic Period Arts and Music 3rd Periodical Test Table of SpecificationDocument2 pagesNeoclassic and Romantic Period Arts and Music 3rd Periodical Test Table of SpecificationJhonabie Suligan CadeliñaNo ratings yet

- Grade 1C - Weekly Plan Week 9 26-12-09Document1 pageGrade 1C - Weekly Plan Week 9 26-12-09G1 Class TeacherNo ratings yet

- Wordsmith 5e Ch01Document12 pagesWordsmith 5e Ch01VIPA ACADEMICNo ratings yet

- Exercise Template OUTCOME 2 SAC (3) For VCE StudentsDocument8 pagesExercise Template OUTCOME 2 SAC (3) For VCE StudentsJennaNo ratings yet

- Prelude No 4 Villalobos Repertoire Level 4 UP1 PDFDocument10 pagesPrelude No 4 Villalobos Repertoire Level 4 UP1 PDFAt YugovicNo ratings yet

- Orsor Grade Composer Composition Main Technical Difficulty or Benefit Other Notes & CommentsDocument28 pagesOrsor Grade Composer Composition Main Technical Difficulty or Benefit Other Notes & Commentsv501100% (8)

- 2nd PT MAPEHDocument4 pages2nd PT MAPEHLV BENDANANo ratings yet

- TeoriaDocument3 pagesTeoriajuanNo ratings yet

- g11 Creative Writing Humss As q2 w1 2 CamagonDocument4 pagesg11 Creative Writing Humss As q2 w1 2 CamagonCharmaine Grace CamagonNo ratings yet

- STEM School English Languages Unit/ Module Cycles Grade 11 Cycle 5 Culture DiversityDocument4 pagesSTEM School English Languages Unit/ Module Cycles Grade 11 Cycle 5 Culture DiversityShahd MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Various Compositions CommentariesDocument17 pagesVarious Compositions Commentariesgreen1458No ratings yet

- Debussy VoilesDocument9 pagesDebussy VoilesMillie Olexa100% (1)

- Improvisation: C F E ADocument5 pagesImprovisation: C F E AotengkNo ratings yet

- VoilesDocument9 pagesVoilesGerardo LunaNo ratings yet

- Character AnalysisaDocument4 pagesCharacter Analysisaapi-239388046No ratings yet

- Pp1 Schemes of Work MusicDocument6 pagesPp1 Schemes of Work Musicvincent mugendiNo ratings yet

- 1A1 Lojano Ronald Ingles PDFDocument2 pages1A1 Lojano Ronald Ingles PDFRonald LojanoNo ratings yet

- Flexies For HornDocument6 pagesFlexies For HornGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- The Man From Snowy River (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Document4 pagesThe Man From Snowy River (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Jurassic Park (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Document4 pagesJurassic Park (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Jurassic Park (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Document4 pagesJurassic Park (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Forrest Gump 1 (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Document4 pagesForrest Gump 1 (2021 - 03 - 04 17 - 56 - 05 UTC)Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Ten Etudes Edited EricsonDocument5 pagesTen Etudes Edited EricsonGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Horn Mouthpiece CatalogDocument30 pagesHorn Mouthpiece CatalogGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Hackleman Routine W ThoughtsDocument3 pagesHackleman Routine W ThoughtsRaulVillodreNo ratings yet

- ExpansionDocument1 pageExpansionGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Boldin Lmea Clinic Fall 2010Document9 pagesBoldin Lmea Clinic Fall 2010Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- TONY HALSTEAD Horn-Practice MethodDocument11 pagesTONY HALSTEAD Horn-Practice MethodGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Arnold Jacobs RespiraciónDocument4 pagesArnold Jacobs RespiraciónMoises David Torres LamedaNo ratings yet

- Mozart'S: Very First Horn ConcertoDocument8 pagesMozart'S: Very First Horn ConcertoGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Daily Routines Student Horn SampleDocument8 pagesDaily Routines Student Horn SampleGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Img 20200501 0014Document1 pageImg 20200501 0014Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Misurazioni Bocchini Corno PDFDocument10 pagesMisurazioni Bocchini Corno PDFAlessandro MacrìNo ratings yet

- Img 20180114 0023Document1 pageImg 20180114 0023Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Ellefson Warm UpDocument16 pagesEllefson Warm UpMatthew Harris100% (11)

- Working With ScalesDocument3 pagesWorking With ScalesGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Notes From Abe Kniaz On Playing The Horn: Collected by Thom GustavsonDocument48 pagesNotes From Abe Kniaz On Playing The Horn: Collected by Thom GustavsonCelso AlvesNo ratings yet

- Faded Walker VetroDocument2 pagesFaded Walker VetroGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Img 20200501 0012Document1 pageImg 20200501 0012Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Img 20200501 0006 PDFDocument1 pageImg 20200501 0006 PDFGaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Img 20200501 0002Document1 pageImg 20200501 0002Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- Img 20200501 0010Document1 pageImg 20200501 0010Gaspare BalconiNo ratings yet

- PDF 20230109 105054 0000Document8 pagesPDF 20230109 105054 0000JYP opparr's plastic pantsNo ratings yet

- Kata LogDocument28 pagesKata Logsarajevo84No ratings yet

- Rigomor Armor Guide - Everything You Need to KnowDocument7 pagesRigomor Armor Guide - Everything You Need to KnowImam FadholiNo ratings yet

- Pachelbel Chaconne in F Minor-Violin 2Document2 pagesPachelbel Chaconne in F Minor-Violin 2Adela UrcanNo ratings yet

- Art in Early CivilizationDocument24 pagesArt in Early CivilizationJomari Gavino100% (1)

- Quarter 1 - Module 3:: Arts and Crafts of Luzon Elements of Beauty and UniquenessDocument27 pagesQuarter 1 - Module 3:: Arts and Crafts of Luzon Elements of Beauty and UniquenessIvan Rey Porras VerdeflorNo ratings yet

- Malmö Symphony Orchestra Audition: Co-Principal TrumpetDocument26 pagesMalmö Symphony Orchestra Audition: Co-Principal TrumpetCristóbal LuisNo ratings yet

- A Middle Bronze Age Ceranic Jug From TelDocument33 pagesA Middle Bronze Age Ceranic Jug From TelPetraki OrlovskiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary ArtDocument7 pagesContemporary ArtFrancis Morales AlmiaNo ratings yet

- Ah - Painters - Gustave DoréDocument1 pageAh - Painters - Gustave DoréNicoleta BadilaNo ratings yet

- LangstonDocument3 pagesLangstoniluvgovNo ratings yet

- First Hindi Rap AlbumDocument4 pagesFirst Hindi Rap AlbumJock Itch100% (1)

- LP 3rd Observation FinalDocument5 pagesLP 3rd Observation FinalMichael AnoraNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 8 Discussion1Document13 pagesMAPEH 8 Discussion1Margielane AcalNo ratings yet

- Destination B1 31 - 32-33 - Review UnfinishedDocument13 pagesDestination B1 31 - 32-33 - Review UnfinishedPhanh NguyenNo ratings yet

- WHLP - G9 Arts Q1 Week 3&4Document3 pagesWHLP - G9 Arts Q1 Week 3&4Uricca Mari Briones SarmientoNo ratings yet

- One Thing I Ask Soprano 1 PDFDocument1 pageOne Thing I Ask Soprano 1 PDFOphelia Sapphire DagdagNo ratings yet

- Top EDM Songs from DJ Tiesto and MoreDocument1 pageTop EDM Songs from DJ Tiesto and MoreEka Adhis ThanayaNo ratings yet

- Megacity São Paulo Home to Over 12 MillionDocument7 pagesMegacity São Paulo Home to Over 12 Millionrosendo javier lopez colindresNo ratings yet

- The Feminine Symbolism of the Serpent in Late 19th Century PoetryDocument24 pagesThe Feminine Symbolism of the Serpent in Late 19th Century PoetryalineNo ratings yet

- Music 6 Q1 Mod 4Document14 pagesMusic 6 Q1 Mod 4Cindy EsperanzateNo ratings yet

- Flip Book. Fold On Dotted Line.: Instructions For Flip BooksDocument3 pagesFlip Book. Fold On Dotted Line.: Instructions For Flip BooksCamyNo ratings yet

- Alesis HR16 HR16B MMT8 ManualDocument72 pagesAlesis HR16 HR16B MMT8 Manualdruids2000No ratings yet

- Payroll data with names, values, benefits and codesDocument40 pagesPayroll data with names, values, benefits and codesBruno MeisterNo ratings yet

- Working with AccompanistsDocument17 pagesWorking with AccompanistszramarioNo ratings yet

- Um Man 2022Document13 pagesUm Man 2022Parhan AzmiNo ratings yet