Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(CR) A Rare Case of Acute Pericarditis Due To SARS-CoV-2 Managed With Aspirin and Colchicine

Uploaded by

Patrick NunsioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(CR) A Rare Case of Acute Pericarditis Due To SARS-CoV-2 Managed With Aspirin and Colchicine

Uploaded by

Patrick NunsioCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Case

Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.12534

A Rare Case of Acute Pericarditis Due to SARS-

CoV-2 Managed With Aspirin and Colchicine

Komandur Thrupthi 1 , Adithya Ganti 1 , Trishna Acherjee 1 , Maham A. Mehmood 1 , Trupti Vakde 2

1. Internal Medicine, BronxCare Health System, Bronx, USA 2. Pulmonary and Critical Care, BronxCare Health System,

Bronx, USA

Corresponding author: Komandur Thrupthi, tkomandu@bronxcare.org

Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 infection presents with predominant respiratory illness. Cardiac injury has been reported in

patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The spectrum of cardiac involvement ranges from pericarditis to

myocarditis. Acute pericarditis attributed to SARS-CoV-2 is rare.

A 68-year-old male with co-morbid condition of hypertension and arthritis presented with chest tightness,

cough and exertional shortness of breath for five days. He was tachycardic at the time of presentation and

cardiac auscultation was positive for pericardial rub. His room air oxygen saturation was 95%. Chest imaging

studies revealed bilateral infiltrate. His electrocardiogram showed ST elevation with diffusely elevated J

point in lead II, III, aVF and V4-V6. Echocardiogram was unrevealing for pericardial effusion and left

ventricular ejection fraction was normal. Serial troponin level did not reveal a rising trend. The

nasopharyngeal swab was positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

use in SARS-CoV-2 positive patient is debatable. The patient had acute pericarditis due to SARS-CoV-2 and

it was treated with high dose aspirin with colchicine.

Acute pericarditis is a rare complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection and can be managed with aspirin and

colchicine.

Categories: Cardiology, Internal Medicine

Keywords: viral pericarditis, covid 19, covid-19 pneumonia

Introduction

Hubei province in China first reported the atypical pneumonia of unknown origin. The etiology of

pneumonia revealed to be a novel virus and was named coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV), also known as

COVID-19, by the health commission of China. It is genetically similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome

(SARS) Coronavirus of 2002 and hence the WHO termed it SARS-CoV-2 [1].

SARS-CoV-2 disease is a global pandemic with a predominant pulmonary manifestation. SARS-CoV-

Review began 11/09/2020

2 generally presents with viral prodromal symptoms and patients with pre-existing co-morbid conditions

Review ended 01/02/2021

Published 01/06/2021 like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease have an adverse outcome. There is ample

evidence to opine on gastrointestinal, hepatic, cardiac, and central nervous system involvement of SARS-

© Copyright 2021

CoV-2. It is estimated that around 20%, of infected, may have a cardiac injury related to SARS-CoV-2 [2].

Thrupthi et al. This is an open access

article distributed under the terms of the The spectrum of cardiac involvement ranges from myocarditis with left ventricular dysfunction to

Creative Commons Attribution License pericarditis [3]. It is challenging to opine on the exact incidence of pericarditis based on a review of current

CC-BY 4.0., which permits unrestricted literature. The majority of evidence of SARS-CoV-2-related pericarditis is based on case reports and it is one

use, distribution, and reproduction in any

of the rare findings of SARS-CoV-2 [4]. Here we present a case of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia who also reported

medium, provided the original author and

chest pain and was diagnosed with acute pericarditis. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are

source are credited.

first-line therapy for the management of acute pericarditis. The emergence of evidence, though uncertain,

of NSAID-related worsening of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia led us to manage pericarditis with colchicine. Our

case report demonstrates a rare presentation of SARS-CoV-2 related to acute pericarditis and the utility of

colchicine in its management.

Case Presentation

A 68-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension and osteoarthritis presented to the

emergency department with a chief complaint of chest tightness for five previous days. The patient also

reported having a dry cough, mild fatigue, and shortness of breath on exertion. On further evaluation, the

patient revealed that his chest pain is sharp, stabbing type with no radiation, persistent with no respiratory

variation, and exacerbation of pain on bending forward. He denied any pain on exertion, any prior episodes

of chest pain, COVID-19 positive sick contact, and prior history of any rheumatological disorder.

On examination, the patient was afebrile with a mean arterial pressure of 93 mm Hg, heart rate of 125 beats

per minute, oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. The physical exam was significant for a pericardial rub

How to cite this article

Thrupthi K, Ganti A, Acherjee T, et al. (January 06, 2021) A Rare Case of Acute Pericarditis Due to SARS-CoV-2 Managed With Aspirin and

Colchicine. Cureus 13(1): e12534. DOI 10.7759/cureus.12534

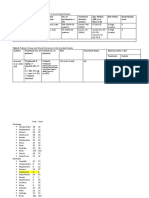

and bilateral extensive expiratory crackles. His troponin on the day of presentation was 17 ng/L with the NT-

proB-type natriuretic peptides (BNP) of 54 pg/ml. Another pertinent laboratory parameter is demonstrated

in Table 1. A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed an ST elevation in leads II, III, AVF, and V4-V6, with

diffusely elevated J point (Figure 1). Findings on the initial X-ray of the chest revealed bilateral diffuse

patchy and peripheral interstitial infiltrates (Figure 2). A computerized tomographic pulmonary angiogram

(CTPA) did not reveal any pulmonary arterial filling defect. However, it revealed extensive peripheral

airspace disease (Figure 3).

LABORATORY FINDINGS Day-1 Day-2

WBC 4.5 5.9

Lymphocyte count 0.9 0.9

ESR 89

D-dimer 486

LDH 338

CRP 38.7 21.90

Ferritin 1733 993

Troponin 16.17 12

TABLE 1: Laboratory parameter at presentation and interval follow-up

WBC: White blood cell; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; CRP: C-reactive protein.

FIGURE 1: Electrocardiogram demonstrates ST-elevation in I, II, III, aVF

and V4-V6 with J point elevation suggestive of acute pericarditis

2021 Thrupthi et al. Cureus 13(1): e12534. DOI 10.7759/cureus.12534 2 of 6

FIGURE 2: X-ray chest demonstrates bilateral opacities

2021 Thrupthi et al. Cureus 13(1): e12534. DOI 10.7759/cureus.12534 3 of 6

FIGURE 3: Cross-section of the CT-chest revealing extensive peripheral

patchy ground glass opacities

The patient was considered to be a COVID-19 suspect (patient under investigation) with pneumonia and

possible myopericarditis. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a 69% ejection fraction with no

pericardial effusion. There were no wall motion abnormalities on the echocardiogram. The nasopharyngeal

swab was performed for Pan-SARS and SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

was reported positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and negative for Pan-SARS panel. Other pertinent laboratory

parameters including urine Legionella and Mycoplasma pneumonia IgM were unrevealing for positive

findings.

The patient’s serial troponins were followed every 8 hours and noted to be normalized in 24 hours of

presentation to 12 ng/L. Given the non-rising trend of troponin level, absence of myocardial wall motion

abnormality, typical pericardial chest pain, and presence of pericardial rub, the patient was managed as

myocarditis. The recommendations prevalent in our institution were followed for the management of

COVID-19 pneumonia. He was initiated on doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily and amoxicillin-

clavulanate 875 mg-125 mg twice daily orally. The patient’s hospital course was stable and he remained

afebrile. He was initiated on aspirin 650 mg tablet three-time daily with colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily. The

patient was not in respiratory distress, was saturating 95% on room air. SARS-CoV-2 was presumed to be a

possible etiology for his acute pericarditis and was planned for rheumatology evaluation on an ambulatory

basis. The patient was not given steroids during hospitalization as he responded well with aspirin and

colchicine. The patient was followed with a telehealth visit and reported resolution of symptoms three

weeks after discharge. He was planned for the outpatient cardiology appointment but failed to follow up.

Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 virus transmits through respiratory droplets, with an incubation period of five days to 10

days [5]. SARS-CoV-2 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme type-2 (ACE-2) receptors of host cells and

after internalization, it leads to the downregulation of ACE2 receptors [6]. ACE2 is expressed in the lungs,

2021 Thrupthi et al. Cureus 13(1): e12534. DOI 10.7759/cureus.12534 4 of 6

kidneys, heart, and blood vessels and is the key enzyme to regulate angiotensin II and angiotensin I. There is

a better understanding of the life cycle of SAR-CoV-2 and most of the clinical manifestation can be from the

viral replication or host response [7].

The majority of the patients with the SARS-CoV-2 have a mild to moderate clinical presentation [8]. The

severe presentations have predominant pulmonary involvement. In our case report, CT imaging was not

used as a tool to assess the severity of the disease but it was mainly based on clinical presentation and

response to treatment. Cardiac complication from SARS-CoV-2 has given insight into another major

predictor of mortality. In a cohort of 466 patients in Wuhan, the presence of cardiac injury, as diagnosed by

elevated serum troponin levels, had 51.2% mortality versus 4.5% in those who did not have cardiac injury

[9]. Acute myopericarditis with subsequent arrhythmia or decrease in left ventricular function may be the

pathophysiology for SARS-CoV-2-related cardiac morbidity [10].

Acute pericarditis is diagnosed if the patient has two of four presenting clinical criteria [11]. These criteria

are: i) chest pain, ii) auscultation findings of pericardial friction-rub, iii) ECG findings suggestive of

pericarditis, and iv) pericardial effusion. Our patient had all characteristics except pericardial effusion.

However, pericardial effusion is present only in up to 60% of patients [12]. Serial troponins and myocardial

dysfunction will aid in assessing myocarditis in conjunction with pericarditis [13]. There was no wall motion

abnormality or low ejection fraction on the echocardiogram in our patient. Hence, the cardiac manifestation

in our patient was likely due to acute pericarditis.

A viral infection is the most common etiology for acute pericarditis. Pericardial inflammation due to viral

replication or immune response explains the pathogenesis of acute pericarditis [14]. Nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first line in pharmacological treatment for acute pericarditis. The

association of NSAIDs and the worsening of COVID-19 is not clear but should be avoided if possible [15].

Colchicine used for recurrent pericarditis can be utilized in acute presentation as well [13, 16]. We performed

an ‘All Field’ PubMed search with "covid 19” AND "pericarditis" and reviewed nine articles as of May 21,

2020. We did not find the use of Colchicine in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 pericarditis. The anti-

inflammatory potency of Colchicine is being evaluated for COVID-19 at this time [17]. However, our case

report demonstrates the utility of managing SARS-CoV-2 pericarditis with Colchicine.

Conclusions

Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection can have a rare presentation with acute pericarditis. Echocardiogram

should be performed to assess wall motion abnormality along with left ventricular ejection fraction to rule

out myocardial involvement. SARS-CoV-2 pericarditis can be treated with Colchicine.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Conflicts of interest: In

compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services

info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the

submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial

relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an

interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other

relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, et al.: Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and

modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci China Life sci. 2020, 63:457-460.

10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5

2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al.: Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19

in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020, 395:1054-1062. 10.1016/S0140-

6736(20)30566-3

3. Aghagoli G, Marin BG, Soliman LB, Sellke FW: Cardiac involvement in COVID-19 patients: risk factors,

predictors, and complications: a review. J Card Surg. 2020, 35:1302-1305. 10.1111/jocs.14538

4. Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X: COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system . Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020,

17:259-260. 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5

5. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, et al.: The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from

publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020, 172:577-582.

10.7326/M20-0504

6. Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD: Renin-angiotensin-

aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382:1653-1659.

10.1056/NEJMsr2005760

7. Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S: COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review . Clin Immunol. 2020,

215:108427. 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427

8. Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, del Rio C: Mild or moderate covid-19 . N Engl J Med. 2020, 383:1757-1766.

10.1056/NEJMcp2009249

2021 Thrupthi et al. Cureus 13(1): e12534. DOI 10.7759/cureus.12534 5 of 6

9. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al.: Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with

COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5:802-810. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950

10. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al.: Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan,

China. Lancet. 2020, 395:497-506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

11. Xanthopoulos A, Skoularigis J: Diagnosis of acute pericarditis . E-J Cardiol Pract. 2017, 15:

12. Imazio M, Brucato A, Maestroni S, Cumetti D, Dominelli A, Natale G, Trinchero R: Prevalence of C-reactive

protein elevation and time course of normalization in acute pericarditis: implications for the diagnosis,

therapy, and prognosis of pericarditis. Circulation. 2011, 123:1092-1097.

10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986372

13. Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, et al.: Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial

diseases executive summary: the task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the

European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004, 25:587-610. 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.002

14. Maisch B, Outzen H, Roth D, et al.: Prognostic determinants in conventionally treated myocarditis and

perimyocarditis—focus on antimyolemmal antibodies. Eur Heart J. 1991, 12:81-87.

10.1093/eurheartj/12.suppl_D.81

15. Russell B, Moss C, Rigg A, Van Hemelrijck M: COVID-19 and treatment with NSAIDs and corticosteroids:

should we be limiting their use in the clinical setting?. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020, 14:1023.

10.3332/ecancer.2020.1023

16. Adler Y, Finkelstein Y, Guindo J, et al.: Colchicine treatment for recurrent pericarditis. A decade of

experience. Circulation. 1998, 97:2183-2185. 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2183

17. Deftereos S, Giannopoulos G, Vrachatis DA, et al.: Colchicine as a potent anti-inflammatory treatment in

COVID-19: can we teach an old dog new tricks?. Eur Heart J - Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020, 6:255.

10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa033

2021 Thrupthi et al. Cureus 13(1): e12534. DOI 10.7759/cureus.12534 6 of 6

You might also like

- The Association Between Covid-19 and ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Variable Clinical Presentations On A Case Report SeriesDocument7 pagesThe Association Between Covid-19 and ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Variable Clinical Presentations On A Case Report SeriesLila FathiaNo ratings yet

- Delayed Acute Myocarditis and COVID 19 Relatedmultisystem in Ammatory SyndromeDocument6 pagesDelayed Acute Myocarditis and COVID 19 Relatedmultisystem in Ammatory SyndromedrKranklNo ratings yet

- Fatal Pulmonary Thromboembolism in SARS CoV 2 Inf - 2020 - Cardiovascular PatholDocument4 pagesFatal Pulmonary Thromboembolism in SARS CoV 2 Inf - 2020 - Cardiovascular PatholsirpitorcasNo ratings yet

- Hemorhagic PRESDocument4 pagesHemorhagic PRESAbdul AzeezNo ratings yet

- Research JournalDocument7 pagesResearch JournalHyacinth A RotaNo ratings yet

- Comment: Covid-19 and The Cardiovascular SystemDocument2 pagesComment: Covid-19 and The Cardiovascular SystemplasmaNo ratings yet

- Case Report - Walking Pneumonia in Novel Coronavirus Disease Covid19Document3 pagesCase Report - Walking Pneumonia in Novel Coronavirus Disease Covid19Walter Pinto TenecelaNo ratings yet

- Revisi A Suspected COVID - 2Document11 pagesRevisi A Suspected COVID - 2Nicholas PranandaNo ratings yet

- Three Cases of Right Heart Thrombus Using POCUS For The Diagnosis of Thromboembolism in COVID-19Document4 pagesThree Cases of Right Heart Thrombus Using POCUS For The Diagnosis of Thromboembolism in COVID-19Yeimer OrtizNo ratings yet

- Report of A Case: Key PointsDocument1 pageReport of A Case: Key PointsLalit GoreNo ratings yet

- Vaccines 10 01286 PDFDocument7 pagesVaccines 10 01286 PDFAarathi raoNo ratings yet

- Unilateral Diaphragm Paralysis With COVID-19 InfectionDocument2 pagesUnilateral Diaphragm Paralysis With COVID-19 InfectiontankNo ratings yet

- Ajrccm-Conference.2021.203.1 Meetingabstracts.a2012Document1 pageAjrccm-Conference.2021.203.1 Meetingabstracts.a2012AngelNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Atypical Presentation of COVID-19 Leading To ARDSDocument4 pagesCase Report: Atypical Presentation of COVID-19 Leading To ARDSEhab MardawiNo ratings yet

- Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in A Young Patient Infected With COVID-19Document4 pagesAcute Decompensated Heart Failure in A Young Patient Infected With COVID-19sw jyNo ratings yet

- Emp2 12098Document4 pagesEmp2 12098Miva MaviniNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0146280620300955 MainDocument21 pages1 s2.0 S0146280620300955 Mainmarialigaya2003No ratings yet

- 2021-Acute Myocarditis After Administration of The BNT162b2 Vaccine Against COVID-19Document3 pages2021-Acute Myocarditis After Administration of The BNT162b2 Vaccine Against COVID-19seguridadyambiente641No ratings yet

- COVID-19 Autopsies - Aqaa062Document9 pagesCOVID-19 Autopsies - Aqaa062Pramod BiradarNo ratings yet

- MainDocument3 pagesMainGAlei LeoNo ratings yet

- Pericarditis: Jenish Dave To:-Dr. Frank KunikDocument24 pagesPericarditis: Jenish Dave To:-Dr. Frank Kunikjenish daveNo ratings yet

- Covid and Cardiovascular SystemDocument4 pagesCovid and Cardiovascular SystemChristine Jane Rodriguez100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S2213007121000289 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2213007121000289 MainHi GamingNo ratings yet

- Estado Del Arte CoronavirusDocument17 pagesEstado Del Arte CoronavirusJosé AñorgaNo ratings yet

- Status of Sars-Cov-2 in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients With Covid-19 and StrokeDocument3 pagesStatus of Sars-Cov-2 in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients With Covid-19 and StrokeSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Bagus 2Document5 pagesBagus 2Jhondris SamloyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading Kelompok 1 From Streptococcal PharyngitisTonsillitis To MyocarditisDocument11 pagesJurnal Reading Kelompok 1 From Streptococcal PharyngitisTonsillitis To MyocarditisFathya ChoirunnisaNo ratings yet

- Rapid Onset Honeycombing Fibrosis Covid 19Document3 pagesRapid Onset Honeycombing Fibrosis Covid 19JimmyNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Autopsies, Oklahoma, USADocument9 pagesCOVID-19 Autopsies, Oklahoma, USARhagaraRhaNo ratings yet

- Acute Cerebral Stroke With Multiple Infarctions and COVID-19, France, 2020Document3 pagesAcute Cerebral Stroke With Multiple Infarctions and COVID-19, France, 2020Rifqi RamdhaniNo ratings yet

- Unilateral Common Carotid Artery Dissection in A PDocument3 pagesUnilateral Common Carotid Artery Dissection in A PidhebeatrickNo ratings yet

- Misdiagnosis in Covid19 Era JACC PDFDocument6 pagesMisdiagnosis in Covid19 Era JACC PDFRirin Efsa JutiaNo ratings yet

- Combination of RT-QPCR Testing and Clinical Features For Diagnosis of Covid-19 Facilitates Management of Sars-Cov-2 OutbreakDocument7 pagesCombination of RT-QPCR Testing and Clinical Features For Diagnosis of Covid-19 Facilitates Management of Sars-Cov-2 OutbreakPrivate HunterNo ratings yet

- E236218 FullDocument5 pagesE236218 Fulldrnaufal ilmiNo ratings yet

- Asma y Covid19Document11 pagesAsma y Covid19Marialy VizcayaNo ratings yet

- Early Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin As Combined Therapy For COVID-19: A Case SeriesDocument8 pagesEarly Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin As Combined Therapy For COVID-19: A Case SeriesTasya OktavianiNo ratings yet

- 145 Other 492 1 18 20220331Document12 pages145 Other 492 1 18 20220331Sarah FajriaNo ratings yet

- 0717 6163 RMC 148 12 1848Document7 pages0717 6163 RMC 148 12 1848ViondaA SotoNo ratings yet

- Lung Ultrasound in The Monitoring of COVID-19 Infection: Author: Yale Tung-ChenDocument4 pagesLung Ultrasound in The Monitoring of COVID-19 Infection: Author: Yale Tung-ChenAndiie ResminNo ratings yet

- Sars-Cov-2: A Potential Novel Etiology of Fulminant MyocarditisDocument3 pagesSars-Cov-2: A Potential Novel Etiology of Fulminant MyocarditisTerry SugijattiNo ratings yet

- The Clinical and Chest CT Features Associated With Severe and Critical COVID-19 PneumoniaDocument5 pagesThe Clinical and Chest CT Features Associated With Severe and Critical COVID-19 PneumoniaNadanNadhifahNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0749070421000439Document21 pagesPi Is 0749070421000439Vlady78No ratings yet

- COVID-19-Associated Carotid Atherothrombosis and StrokeDocument3 pagesCOVID-19-Associated Carotid Atherothrombosis and StrokeChavdarNo ratings yet

- Brojakowska 2020Document11 pagesBrojakowska 2020Anett Pappné LeppNo ratings yet

- Outcomes in Patients With COVID-19 Infection Taking ACEI/ARBDocument4 pagesOutcomes in Patients With COVID-19 Infection Taking ACEI/ARBfk unswagatiNo ratings yet

- 10.1016@j.yjmcc.2020.04.031 Hipertensi Dan Covid 19Document22 pages10.1016@j.yjmcc.2020.04.031 Hipertensi Dan Covid 19Sulis TioNo ratings yet

- Pneumothorax in Critically COVID-19 Patients With Mechanical VentilationDocument5 pagesPneumothorax in Critically COVID-19 Patients With Mechanical VentilationNadyaNo ratings yet

- Case Report COVID-19 and Pulmonary Mycobacterium Tuberculosis CoinfectionDocument4 pagesCase Report COVID-19 and Pulmonary Mycobacterium Tuberculosis CoinfectionNindie AulhieyaNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Injury and Myocarditis in Sars-Cov-2 PatientsDocument4 pagesMyocardial Injury and Myocarditis in Sars-Cov-2 PatientsdiaconuNo ratings yet

- Covid-Stroke 1 PDFDocument18 pagesCovid-Stroke 1 PDFMelya UmbulNo ratings yet

- 449 Marlyn A - 062018 PDFDocument2 pages449 Marlyn A - 062018 PDFVibhor Kumar JainNo ratings yet

- Medical Virology Jan 2021Document9 pagesMedical Virology Jan 2021cdsaludNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: David SweetDocument204 pagesAcute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: David SweetJelenaNo ratings yet

- Persistent Complete Atrioventricular Block in A Covid PatientDocument6 pagesPersistent Complete Atrioventricular Block in A Covid PatientIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Stroke Associated With Novel Coronavirus 2019 A Report of Three CasesDocument6 pagesIschemic Stroke Associated With Novel Coronavirus 2019 A Report of Three CasesDewianggreini DandaNo ratings yet

- Coexistence of COVID-19 and Acute Ischemic Stroke Report of Four CasesDocument3 pagesCoexistence of COVID-19 and Acute Ischemic Stroke Report of Four CasessomyahNo ratings yet

- 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Taiwan: Reports of Two Cases From Wuhan, ChinaDocument4 pages2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Taiwan: Reports of Two Cases From Wuhan, ChinaClaav HugNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3 - Disfuncion NeurologicaDocument7 pagesArticulo 3 - Disfuncion NeurologicaClaudia SalasNo ratings yet

- Outcomes of Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury in COVID 19 Infection An Observational StudyDocument9 pagesOutcomes of Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury in COVID 19 Infection An Observational StudyJulio YulitaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case Reports - 2020 - Koirala - A Rare Case of Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy With IUD in Situ A Case Report FromDocument4 pagesClinical Case Reports - 2020 - Koirala - A Rare Case of Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy With IUD in Situ A Case Report FromPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Acute Ischaemic Stroke in Infective Endocarditis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Treated With Reperfusion TherapyDocument13 pagesAcute Ischaemic Stroke in Infective Endocarditis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Treated With Reperfusion TherapyPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- UC Irvine: Clinical Practice and Cases in Emergency MedicineDocument6 pagesUC Irvine: Clinical Practice and Cases in Emergency MedicinePatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Ruptured Primary Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy, A Rare Case ReportDocument3 pagesRuptured Primary Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy, A Rare Case ReportPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy in The Presence of An Intrauterine DeviceDocument5 pagesRuptured Ectopic Pregnancy in The Presence of An Intrauterine DevicePatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Notes ColchicineDocument1 pageNotes ColchicinePatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- (RCT) Cardiovascular Injuries After Covid-19 InfectionDocument7 pages(RCT) Cardiovascular Injuries After Covid-19 InfectionPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of COVID-19 Related Myocarditis, Insights On Management and OutcomeDocument7 pagesSystematic Review of COVID-19 Related Myocarditis, Insights On Management and OutcomePatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy in The Presence of An Intrauterine DeviceDocument5 pagesRuptured Ectopic Pregnancy in The Presence of An Intrauterine DevicePatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Clinically Suspected Myocarditis Temporally Related To COVID-19 Vaccination in Adolescents and Young AdultsRunningDocument29 pagesClinically Suspected Myocarditis Temporally Related To COVID-19 Vaccination in Adolescents and Young AdultsRunningPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Notes ColchicineDocument1 pageNotes ColchicinePatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Clinical Course and Risk Factors For Mortality of Adult Inpatients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Retrospective Cohort StudyDocument9 pagesClinical Course and Risk Factors For Mortality of Adult Inpatients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Retrospective Cohort StudyJoão PascoalNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case Reports - 2020 - Koirala - A Rare Case of Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy With IUD in Situ A Case Report FromDocument4 pagesClinical Case Reports - 2020 - Koirala - A Rare Case of Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy With IUD in Situ A Case Report FromPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of The Infectious Complications of Colchicine and The Use of Colchicine To Treat InfectionsDocument12 pagesA Systematic Review of The Infectious Complications of Colchicine and The Use of Colchicine To Treat InfectionsPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Neurological Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan China, A Retrospective Case Series StudyDocument26 pagesNeurological Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan China, A Retrospective Case Series StudyPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Comorbilidades Asociadas A Mortalidad Covid-Eeuu-2020Document11 pagesComorbilidades Asociadas A Mortalidad Covid-Eeuu-2020RONALD. D VIERA .MNo ratings yet

- (CR PERICARDITIS) Challenges in Managing Pericardial Disease Related To Post Viral Syndrome After COVID-19 InfectionDocument6 pages(CR PERICARDITIS) Challenges in Managing Pericardial Disease Related To Post Viral Syndrome After COVID-19 InfectionPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Simplified Rules of BadmintonDocument2 pagesSimplified Rules of BadmintonPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- (Hydroxychloroquine/ Azithromycin/antiretro Virals/low Molecular Weight Heparin)Document4 pages(Hydroxychloroquine/ Azithromycin/antiretro Virals/low Molecular Weight Heparin)Patrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 VaksinDocument136 pagesCovid-19 VaksinPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- 00547-2020 Full PDFDocument56 pages00547-2020 Full PDFirmaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Course and Risk Factors For Mortality of Adult Inpatients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Retrospective Cohort StudyDocument9 pagesClinical Course and Risk Factors For Mortality of Adult Inpatients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A Retrospective Cohort StudyJoão PascoalNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Outcome Comparison of Ischemic Stroke With and Without Atrial Fibrillation 9055Document5 pagesThe Clinical Outcome Comparison of Ischemic Stroke With and Without Atrial Fibrillation 9055Patrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Neuropathy As A Complication of SARS-Cov-2Document5 pagesPeripheral Neuropathy As A Complication of SARS-Cov-2Patrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Paed COVID 19 Case P PUL 2020Document6 pagesPaed COVID 19 Case P PUL 2020Minaz PatelNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of COVID-19 Infection in Beijing PDFDocument7 pagesCharacteristics of COVID-19 Infection in Beijing PDFPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- A Comparative-Descriptive Analysis of Clinical Characteristics in 2019-Coronavirus-Infected Children and AdultsDocument28 pagesA Comparative-Descriptive Analysis of Clinical Characteristics in 2019-Coronavirus-Infected Children and AdultsPatrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Ghid 2016 Fibrilatia AtrialaDocument90 pagesGhid 2016 Fibrilatia AtrialaIon PetescuNo ratings yet

- Ehx 039Document1 pageEhx 039Patrick NunsioNo ratings yet

- Why We Sleep The New Science of Sleep and Dreams BDocument3 pagesWhy We Sleep The New Science of Sleep and Dreams BmjhachemNo ratings yet

- Act Assessment Practice Reading PassageDocument3 pagesAct Assessment Practice Reading PassageThanh HàNo ratings yet

- Consent Explanation Document (English Version)Document4 pagesConsent Explanation Document (English Version)SIMEON KINTUNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) : Prakash Thakulla InternDocument38 pagesPostpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) : Prakash Thakulla InternPrakash ThakullaNo ratings yet

- Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation StudentDocument11 pagesSurveillance and Outbreak Investigation Studentnura meccaNo ratings yet

- PresbycusisDocument2 pagesPresbycusisRomano Paulo BanzonNo ratings yet

- English VersionDocument20 pagesEnglish Versionistinganatul muyassarohNo ratings yet

- Smart Asthma ConsoleDocument35 pagesSmart Asthma ConsoleMohamad Mosallam AyoubNo ratings yet

- Drug Education Definition of TermsDocument6 pagesDrug Education Definition of TermsQayes Al-QuqaNo ratings yet

- CDC's Guidelines For Environmental Infection ControlDocument242 pagesCDC's Guidelines For Environmental Infection ControlGeorge HarrisonNo ratings yet

- Resolution AgeismDocument7 pagesResolution AgeismRoseAnn DivinaNo ratings yet

- Millet Grains: Nutritional Quality, Processing, and Potential Health BenefitsDocument16 pagesMillet Grains: Nutritional Quality, Processing, and Potential Health BenefitsBala NairNo ratings yet

- Becknam-Ref VrednostiDocument44 pagesBecknam-Ref VrednostialisaNo ratings yet

- ESR Vs CRPDocument6 pagesESR Vs CRPMuhammad Imran MirzaNo ratings yet

- Post Basic Nursing SyllabusDocument112 pagesPost Basic Nursing SyllabusSathish Kumar67% (3)

- Naga College Foundation, Inc.: Case Study On AnemiaDocument66 pagesNaga College Foundation, Inc.: Case Study On AnemiaAnnie Lou AbrahamNo ratings yet

- First Aid Introduction-2022Document107 pagesFirst Aid Introduction-2022Chipego NyirendaNo ratings yet

- Vital Statistics Rapid Release: Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates For 2021Document16 pagesVital Statistics Rapid Release: Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates For 2021Verónica SilveriNo ratings yet

- Do-6 ReadingDocument7 pagesDo-6 ReadingNazar KuzivNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Pridiction Using Machine LearningDocument31 pagesDiabetes Pridiction Using Machine LearningAbhishekNo ratings yet

- Causes and Characteristics of Horizontal Positional NystagmusDocument9 pagesCauses and Characteristics of Horizontal Positional NystagmusRudolfGerNo ratings yet

- 9485 R0 NuNec Surgical Technique 8-30-16Document24 pages9485 R0 NuNec Surgical Technique 8-30-16BobNo ratings yet

- 5 Easy Ways To Cheat A Jet LagDocument3 pages5 Easy Ways To Cheat A Jet LagRuchi AhujaNo ratings yet

- Nidaan Swasthya Bima Policy BrochureDocument10 pagesNidaan Swasthya Bima Policy Brochureimpbithin96No ratings yet

- Disorders of The EarDocument8 pagesDisorders of The EarVinz Khyl G. CastillonNo ratings yet

- International Vision Rehabilitation StandardsDocument156 pagesInternational Vision Rehabilitation StandardsGuadalupeNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 June 2000Document6 pagesPaper 2 June 2000MSHNo ratings yet

- Potential Indonesian Herbs To Develop A Mix Herbal Immunomodulator Supplement A Hermeneutic Systematic ReviewDocument6 pagesPotential Indonesian Herbs To Develop A Mix Herbal Immunomodulator Supplement A Hermeneutic Systematic Reviewdhiva YunitaNo ratings yet

- Renr Week 7th 2017 Questions SheetDocument21 pagesRenr Week 7th 2017 Questions SheetSasha UterNo ratings yet

- Delivery of CH ServicesDocument39 pagesDelivery of CH ServicesAnand gowdaNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)