Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Owen's Critique of War Remembrance

Uploaded by

Mohsin IqbalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Owen's Critique of War Remembrance

Uploaded by

Mohsin IqbalCopyright:

Available Formats

CONTEXTUALIZE

- Written by English poet Wilfred Owen who was born in the late 19th century and died in battle in the early 20th

century during the first world war

- During his time in the war Owen was diagnosed as suffering from shell shock and was sent to Craiglockhart War

Hospital in Edinburgh for treatment. It was during treatment at Craiglockhart that he met fellow poet Siegfried

Sassoon who inspired him to translate his experiences into poetry

- This poem, alongside many other poems by Owen, are a commentary on the first World War, which took place

from 1914 to 1918

OVERVIEW

- In the first stanza, the poem looks at some of the ways that dead soldiers might be honored and transforms

them into the sounds and sights of war itself. The rituals referenced—the ringing of bells, prayers in churches,

singing choirs—are presented as “mockeries” that fail to do justice to the fallen. That is, these things are so

removed from the horrible reality of war that they mock the people they are supposed to honor.

- In the second stanza, the poem moves to describe more fitting forms of tribute. Instead of the weak light of

remembrance candles, for example, the speaker suggests honoring the “holy glimmers of goodbyes” in the

soldier's eyes—that is, the dying light of life in their eyes as they realize that their time is up. Then, the speaker

goes on to mention the “pallor of girls’ brows,” the “tenderness of patient minds,” and the “drawing-down of

blinds” each day. Each of these, the speaker suggests, is a more honest form of tribute.

PURPOSE

- Owen wanted to depict the brutal and pointless nature of warfare

STRUCTURE

- Written with the structure of a Petrarchan sonnet (14 lines with a rhyming couplet at the end) but the rhyme

scheme of a Shakespearean sonnet. A Petrarchan sonnet is a form of poetry usually centred on love but this is

used to illustrate how love for one’s country could lead to death, like in the case of the soldiers

THEMES

- Brutality and pointlessness of war

→ “Anthem for Doomed Youth” asks the reader not to romanticize war (which is accentuated by the

irony of its sonnet forms, which generally deals with themes of love and romance). Though it’s a lyrical

and beautiful poem, its power comes from the way in which it brings the horrors of war to life. War is

held up to the light, exposed as futile, horrific, and tragic.

- Ritual and remembrance

→ “Anthem for Doomed Youth” criticizes the usual forms of ritual and tribute used to commemorate

people who have died in war. It’s not saying that these rituals don’t have their place, but rather that

they're not enough in the face of war's horrors. In the second stanza, the poem presents memory,

kindness, and gratitude as more fitting memorials.”

TONE

As will be seen in the poem: grief-stricken and morose

MIPs. in this commentary I will be returning to three main ideas:

- The main themes of this poem

- How Owen utilizes weaponry in the poem as a way to comment on the brutal and pointless nature

of warfare

- The ways in which Owen highlights the mistreatment of soldiers in the war

LINE-BY-LINE ANALYSIS

Anthem for doomed youth

- Irony: “anthem,” is used ironically as well, because an anthem expresses unity and functions as a celebratory

and happy hymn, whereas in this case, it is bitterly sarcastic since there is a large amount of grief being

conveyed in the poem. It is, then, a kind of protest poem—subverting the usual use of “anthem” as a symbol of

nationalism (that is, taking undue pride in your home nation) into an anti-war message.

- Had originally had “dead” instead of “doomed” in the title, changed it to create greater sense of helplessness as

it seemed that the youth’s fate was sealed

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

- Religious imagery: “passing bells,” – religious imagery to allude to funeral bells – implying that the soldiers are

dead.

- diction: “these,” his diction is used to create detachment between reader and soldiers to represent how the

government thought of them as commodities, as “these,” is a demonstrative pronoun.

- Simile: “as cattle,” – to represent how the soldiers are dying in “herds” on the frontline like animals in a

slaughterhouse. It also compares their treatment (like the lack of a funeral) to the treatment of cows, expressing

the extent to which soldiers have been dehumanised

- Rhetorical question: Opens with the rhetorical question. This rhetorical question provokes reader thought,

making readers question why the soldiers are not given funerals – shock the readers to the realities of war and

how the soldiers’ deaths are taken.

- Hypophora: The rhetorical question acts as a hypophora given that the question is asked at the beginning of the

stanze and is answered in the rest of the stanze.

- The speaker questions what good "passing-bells"—and other forms of ritual—really do in the face of such

indiscriminate slaughter. In other words, this first line introduces the idea that there is too much of a disconnect

between the pretentious symbolism of religious ceremony and the grim realities of warfare.

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

- Personification: “monstrous anger of the guns.” – expresses the chaos and pandemonium of the soldiers’

deaths – juxtaposed to the peaceful deaths that people think they deserve and the contents of the first line. This

signifies the beginning of the use of auditory imagery throughout the poem which acts, in a way, to replace the

absent “passing-bells”

- Personification: “stuttering rifle,” to add to the sense of chaos and express the rage of the person holding the

rattle, as stuttering is something people do when they are infuriated, hence the expression, “stuttered with

rage,” – sense of chaos created and this is juxtaposed to the peaceful deaths that people think they deserve and

the contents of the first line

- Anaphora: Lines 2 and 3 make similar points. They are both about the sounds of war, and both begin with

anaphora of the repeated "Only", which aids in Owen’s emphasis on the personification of the weaponry that

heavily juxtaposes with the rest and silence which one may expect for a nation’s soldiers when they die

- Alliteration: “rifle’s rapid rattle,” – alliteration of ‘r’ sound emphasises the stuttering previously mentioned and

reinforces the rage of the enemy – sense of chaos– juxtaposed to the peaceful deaths that people think they

deserve and the contents of the first line.

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

- Onomatopoeia: “patter,” – onomatopoeia that sounds like gun firing. The soft sound of "patter" is deliberately

out of place here, helping to portray actual prayers (and traditional responses to soldiers' deaths more

generally) as, essentially, meaningless utterances.

- Diction: “hasty orisons,” – hasty means rushed, connotes a lack of care, shows how little effort went into the

last rites of the men as metaphorically represented through the word orisons, which is an archaic term for

prayers. Expressing his disheartenment with the church to the public, while reinforcing the theme of death.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

- Parallelism: “No mockeries…no prayers nor bells.” – the mockeries are the prayers and bells, this parallel is

reinforced by the repetition of the word no before each of the words. Owen is saying that the funerals

performed glorify their deaths, since they die like cattle. This is also an extension of Owen’s own negative view

of the church for aiding the government in performing the shoddy funerals that are not fit for honourable

soldiers and also for persuading men to go to war, as the churches preached pro war propaganda.

- Diction: use of ,”nor,” and ,”no,” in the same line create a sense of deprivation, highlight how the soldiers have a

lack of amenities and essentials on the battlefield, increase pity for soldiers

- Caesura: The caesura partway through makes line 5 feel a little slower and more mournful as well, compared

with the brutal depictions of the first half of the stanza.

- Explicit message: Line 5 makes the poem's stance on remembrance rituals explicitly clear: "passing-bells,"

"orisons," "choirs" and so on are all "mockeries." That is, rather than paying tribute to fallen soldiers, they're

actually more of an insult—because they're so divorced from the reality of warfare.

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

- Metaphor: The "choirs" of line 6 are, in fact, the horrific sounds of the "shells" (explosive and deadly projectiles)

as they rain over the soldiers' heads. These sounds are metaphorically described as "shrill, demented choirs,"

like a choir from hell singing in praise of death and destruction.

- Personification: idea of a choir (peaceful, serene) juxtaposed to the adjective used (demented) mocking the

divinity and peace that is presented by the Church. This enhances the continued criticism of Church by Owen.

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

- Volta: the volta is the turn of thought or an argument in a sonnet. This is seen in line 8 because the poem's

setting shifts from the "theater" of war (the area where the conflict actually takes place) to the country from

which the soldiers in question originally came. Whereas lines 1 to 7 showcase the horrible and hellish of sounds

weaponry, the sound (that of a bugle, which is a simple brass instrument) in line 8 instead relates specifically to

home.

- Diction: “bugles,” – Bugles were commonly used on the front lines of war to convey instructions or information

but they also have a commemorative use. The speaker evokes this commemorative use of bugles by

characterizing their tune as the melodic sound of loss and longing

- Sibilance: “sad shires,” – alliteration to emphasise how the shires (different parts of Britain) are very sure that

their men will die in the war, morose tone created. This also emphasizes Owen’s criticism of war and its

pointlessness

What candles may be held to speed them all?

- Synecdoche in candles which are used as funeral imagery to represent remebrance as a whole

- Rhetorical question: implies that no candles are used to send them into the afterlife, no proper funeral. This

question acts as a hypophora once more as it is asked at the beginning of the stanze and is answered in the rest

of the stanza.

- Religious allusion: Speed - religious allusion given that the speaker asks what candles can help the souls of the

dead find their way ("speed") to the afterlife

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

- Diction: “boys,” – shows how young the soldiers are and how innocent they are (denotation), increasing the

tragedy of their deaths.

- “in their eyes,” – implies tears, shows that tears are more genuine expressions of grief than the superficial

funerals

- Religious imagery: “hands of boys,” – religious imagery related to funeral because altar boys carry candles to

the casket during funeral

- Litote; not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes. Allows Owen to put emphasis on what isn’t happening instead

of what is.

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

- Euphemism: “holy glimmers of goodbye,” – (conveys their suffering) euphemism for suffering of soldiers before

they die, showing how the soldiers died without honour, because the glimmers form when people are about to

cry, hence explaining that they were crying before they died. You only cry if you’re really suffering emotionally,

reiterating the theme of suffering and therefore increasing the audience’s sympathy for the men

- Sibilance: Line 11—makes use of sibilance (both alliterative and consonantal) to create a whispering quality

that's suggestive of weakness as life ebbs away:

The pallor of girls' brows shall be their pall;

- Definition: “pall” is a cloth laid over a coffin—but again, many of these young men won't have funerals, which

means that they won't have coffins over which a pall could be draped.

- Multiple meanings: “Pallor” has a kind of double meaning—it relates to being pale, but can also mean

"deathlike." In other words, the "girls' brows" have been touched by death in their own way. Through this

image, the speaker suggests that the profound grief of those left behind is actually a more fitting way to honor

the dead than any of the formal rituals discussed in previous lines.

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

- Diction: “flowers,” reinforces existing funeral imagery to highlight a sense of tragedy. Instead of the temporary

beauty of "flowers," the sacrifices of WWI will be honored by peace.

- “tenderness of patient minds,” – the speaker hopes that part of the sorrowful legacy of the war will be "the

tenderness of patient minds." That is, the speaker hopes that one of the effects of such a devastating war will

eventually be to make such an event less likely in the future.

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

- Diction: dusk refers to the time period during which soldiers could relax and rest. It is also the last part of the

day and this could parallel how the soldiers’ lives are ending and in their end, the soldiers can finally be at

peace. This punctuates the theme of death and adds to the morose tone of the extract.

- Allusion: “drawing-down of blinds.” – practise when one’s family member died, home had blinds drawn to

honour the dead. This adds to the morose tone of the last line by showing how at dusk, more blinds are drawn,

i.e more dead soldiers.

- Sibilance: Both lines in the couplet use sibilance, drawing the poem to its hushed close.

You might also like

- The Soldier by Rupert BrookeDocument1 pageThe Soldier by Rupert BrookeAarti Naidu100% (1)

- Now Let No Charitable Hope - NotesDocument2 pagesNow Let No Charitable Hope - NotesEram IftikharNo ratings yet

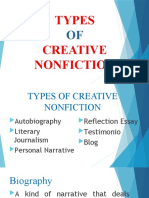

- Types of Creative Nonfiction Under 40 CharactersDocument23 pagesTypes of Creative Nonfiction Under 40 CharactersLeah Joy Dadivas100% (2)

- Ib English WaDocument8 pagesIb English Waapi-376581373No ratings yet

- DISABLED - NotesDocument4 pagesDISABLED - NotesLenora LionheartNo ratings yet

- (Medieval European Studies, 18) Stephen J. Harris - Bede and Aethelthryth - An Introduction To Christian Latin Poetics-West Virginia University Press (2016)Document362 pages(Medieval European Studies, 18) Stephen J. Harris - Bede and Aethelthryth - An Introduction To Christian Latin Poetics-West Virginia University Press (2016)MSTNo ratings yet

- Owen's Critique of War RemembranceDocument5 pagesOwen's Critique of War RemembranceMohsin IqbalNo ratings yet

- Strange Meeting by Wilfred OwenDocument9 pagesStrange Meeting by Wilfred Owenbritney campbellNo ratings yet

- Thrushes: Ted HughesDocument6 pagesThrushes: Ted HughesNosaiba EfratNo ratings yet

- The Send Off - CommentaryDocument4 pagesThe Send Off - CommentaryZachary Iqbal100% (1)

- Blessing Anlysis (Edited)Document3 pagesBlessing Anlysis (Edited)Tyng ShenNo ratings yet

- PoetDocument2 pagesPoetROSERA EDUCATION POINTNo ratings yet

- Plot Summary: Facebook Page MA / BS English University of Sargodha PakistanDocument15 pagesPlot Summary: Facebook Page MA / BS English University of Sargodha PakistanMohsin Iqbal100% (1)

- The Soldier SummaryDocument7 pagesThe Soldier SummarySalsabeel NagiNo ratings yet

- Death of A Salesman Summary and AnalysisDocument3 pagesDeath of A Salesman Summary and AnalysisAnGel LieNo ratings yet

- She Was A Phantom of Delight'Document5 pagesShe Was A Phantom of Delight'Daisy0% (1)

- Mourning Becomes ElectraDocument3 pagesMourning Becomes ElectraJauhar JauharabadNo ratings yet

- Dryden's Mock-Heroic Satire Attacking Fellow Poet Thomas ShadwellDocument13 pagesDryden's Mock-Heroic Satire Attacking Fellow Poet Thomas ShadwellMadhulina Choudhury100% (1)

- The Decadence of True Humanity in The Importance of Being EarnestDocument5 pagesThe Decadence of True Humanity in The Importance of Being EarnestAdilah ZabirNo ratings yet

- Tradition and The Individual TalentDocument5 pagesTradition and The Individual TalentJashim UddinNo ratings yet

- Fasting, Feasting by Antia Desai, Houghton Mifflin CompanyDocument10 pagesFasting, Feasting by Antia Desai, Houghton Mifflin CompanyGLOBAL INFO-TECH KUMBAKONAMNo ratings yet

- (Early Modern Literature in History) Kathleen Miller (Auth.) - The Literary Culture of Plague in Early Modern England-Palgrave Macmillan Uk (2016) PDFDocument247 pages(Early Modern Literature in History) Kathleen Miller (Auth.) - The Literary Culture of Plague in Early Modern England-Palgrave Macmillan Uk (2016) PDFsomabswsNo ratings yet

- How Does Owen Convey, in Disabled', What The Young Man Has Lost in War?Document2 pagesHow Does Owen Convey, in Disabled', What The Young Man Has Lost in War?DeepNo ratings yet

- Larkin Ambulances1Document4 pagesLarkin Ambulances1Sumaira MalikNo ratings yet

- Methapor and Idiom of The Poem From The Hollow Men by T S EliotDocument10 pagesMethapor and Idiom of The Poem From The Hollow Men by T S EliotDDNo ratings yet

- Edmund Spenser (1552 - 1599) Like As A ShipDocument5 pagesEdmund Spenser (1552 - 1599) Like As A ShipHaneen Al Ibrahim100% (1)

- Captive - NotesDocument7 pagesCaptive - NotesLindie Van der MerweNo ratings yet

- 1) To Trouble The Living StreamDocument6 pages1) To Trouble The Living StreamRifa Kader DishaNo ratings yet

- Hawk RoostingDocument17 pagesHawk RoostingRitankar RoyNo ratings yet

- He Never Expected So MuchDocument7 pagesHe Never Expected So Muchlakshmipriya sNo ratings yet

- MahabharatDocument21 pagesMahabharatDevendra KumawatNo ratings yet

- Thistles Ted HughesDocument2 pagesThistles Ted Hugheslghobrial2012100% (1)

- Dulce Et Decorum Est SummaryDocument1 pageDulce Et Decorum Est SummarySrigovind Nayak100% (1)

- Shakespeare's Sonnet 55 Analyzed Through New Critical and Formalist LensesDocument2 pagesShakespeare's Sonnet 55 Analyzed Through New Critical and Formalist LensesTündi TörőcsikNo ratings yet

- Poem Analysis The Man He KilledDocument4 pagesPoem Analysis The Man He KilledRachael RazakNo ratings yet

- Riders To The SeaDocument45 pagesRiders To The SeaAshique ElahiNo ratings yet

- The Morning Is FullDocument3 pagesThe Morning Is FullLoewe Isabel LalicNo ratings yet

- Modern Drama from Shaw to Theatre of the AbsurdDocument12 pagesModern Drama from Shaw to Theatre of the AbsurdAttila ZsohárNo ratings yet

- A Thousand Years of Good Prayers LitChartDocument15 pagesA Thousand Years of Good Prayers LitChartGanadhipati Anissha AryanNo ratings yet

- After BlenheimDocument3 pagesAfter Blenheimjini deyNo ratings yet

- Frost - "Home Burial"Document5 pagesFrost - "Home Burial"Alicia Y. Wei100% (2)

- Sunday Morning: by Wallace StevensDocument4 pagesSunday Morning: by Wallace StevensMarinela CojocariuNo ratings yet

- Piano Poem AnalysisDocument2 pagesPiano Poem AnalysisBen ChengNo ratings yet

- Metaphysical Poets: George Herbert Go To Guide On George Herbert's Poetry Back To TopDocument10 pagesMetaphysical Poets: George Herbert Go To Guide On George Herbert's Poetry Back To TopEya Brahem100% (1)

- Biography of Kamala Das: Kamala Surayya / Suraiyya Formerly Known As Kamala Das, (Also Known As Kamala Madhavikutty, PenDocument2 pagesBiography of Kamala Das: Kamala Surayya / Suraiyya Formerly Known As Kamala Das, (Also Known As Kamala Madhavikutty, Penkitchu007No ratings yet

- Eliot's "The Hollow MenDocument6 pagesEliot's "The Hollow MenIkram TadjNo ratings yet

- Uniqueness of Donne As A Poet of LoveDocument9 pagesUniqueness of Donne As A Poet of LoveAbhiShekNo ratings yet

- Blake's Iconic Poem 'The Tyger' AnalyzedDocument4 pagesBlake's Iconic Poem 'The Tyger' Analyzedenglish botanyNo ratings yet

- The Romantic PoetsDocument4 pagesThe Romantic PoetsbaksiNo ratings yet

- Jayanta MahapatraDocument10 pagesJayanta MahapatrasanamachasNo ratings yet

- Philip Larkin Toads8585Document3 pagesPhilip Larkin Toads8585lisamarie1473No ratings yet

- AdoniasDocument7 pagesAdoniasShirin AfrozNo ratings yet

- Monish B V - We Are The Music MakersDocument2 pagesMonish B V - We Are The Music MakersVijay Kumar100% (1)

- Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good NightDocument3 pagesDo Not Go Gentle Into That Good NightRinku GhoshNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On Modern DramaDocument30 pagesTerm Paper On Modern DramaAsad Ullah100% (1)

- The Contribution of Charles Lamb As An Essayist To The English LiteratureDocument5 pagesThe Contribution of Charles Lamb As An Essayist To The English LiteratureHimanshuNo ratings yet

- The Faerie Queen (Spenser)Document2 pagesThe Faerie Queen (Spenser)Amy Fowler100% (1)

- Carol Ann DuffyDocument3 pagesCarol Ann DuffyRed TanNo ratings yet

- Duffy V LarkinDocument5 pagesDuffy V Larkinapi-353984031No ratings yet

- Mean TimeDocument6 pagesMean Timeapi-438963588No ratings yet

- Essay Question Futility Next WarDocument2 pagesEssay Question Futility Next Warapi-299201285100% (1)

- The Chimney Sweeper SoI & SoEDocument2 pagesThe Chimney Sweeper SoI & SoEGeorge KnightNo ratings yet

- Poem - The Runaway Slave at Pilgrims Point - Elza Browning - Tariq Makki OrginialDocument4 pagesPoem - The Runaway Slave at Pilgrims Point - Elza Browning - Tariq Makki Orginialapi-313775083No ratings yet

- Wilfred Owen - Dulce Et Decorum Est, Text of Poem and NotesDocument4 pagesWilfred Owen - Dulce Et Decorum Est, Text of Poem and NotesMalcolm J. SmithNo ratings yet

- Thomas Gray's Popular Elegy Explores Death and EqualityDocument2 pagesThomas Gray's Popular Elegy Explores Death and EqualitysdvsvbsNo ratings yet

- RenessansDocument117 pagesRenessansChetanya MundachaliNo ratings yet

- Study On The Images of The Code Hero Fighting Alone in Hemingway's WorksDocument6 pagesStudy On The Images of The Code Hero Fighting Alone in Hemingway's WorksMohsin IqbalNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Themes and Artistic Features of For Whom The Bell TollsDocument3 pagesAnalysis of The Themes and Artistic Features of For Whom The Bell TollsTatjana BarthesNo ratings yet

- Wilfred Owen-An IntroductionDocument7 pagesWilfred Owen-An IntroductionMohsin IqbalNo ratings yet

- Irony and Nostalgia in Hanif'S A Case of Exploding Mangoes: A Postmodern AnalysisDocument13 pagesIrony and Nostalgia in Hanif'S A Case of Exploding Mangoes: A Postmodern AnalysisMohsin IqbalNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Themes and Artistic Features of For Whom The Bell TollsDocument3 pagesAnalysis of The Themes and Artistic Features of For Whom The Bell TollsTatjana BarthesNo ratings yet

- The Inwardness of James Joyce's Story, "The Dead"Document14 pagesThe Inwardness of James Joyce's Story, "The Dead"Billy BoyNo ratings yet

- Wilfred Owen-An IntroductionDocument7 pagesWilfred Owen-An IntroductionMohsin IqbalNo ratings yet

- The Shutters by Ahmed BouananiDocument118 pagesThe Shutters by Ahmed BouananiPranay DewaniNo ratings yet

- Second Quarter Activity SheetsDocument7 pagesSecond Quarter Activity SheetsAnjieyah Bersano FabroNo ratings yet

- World Literature ElementsDocument13 pagesWorld Literature ElementsErica RabangNo ratings yet

- Oscar Alfaro biography and poemsDocument2 pagesOscar Alfaro biography and poemstemlor100% (3)

- +12 English DiscoursesDocument24 pages+12 English DiscoursesNASREEN KADERNo ratings yet

- English Literature Project XIDocument6 pagesEnglish Literature Project XIAnushka MajumderNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 THE SPANISH PERIOD (1565-1898) : Philippine LiteratureDocument6 pagesLesson 3 THE SPANISH PERIOD (1565-1898) : Philippine LiteratureJerome BautistaNo ratings yet

- American Literary CriticismDocument4 pagesAmerican Literary CriticismMihaela MunteanuNo ratings yet

- U2L01 - Activity Guide - Exploring Web PagesDocument1 pageU2L01 - Activity Guide - Exploring Web PagespeggyNo ratings yet

- Explore Types of Poetry and Lyric FormsDocument24 pagesExplore Types of Poetry and Lyric FormsJave MamontayaoNo ratings yet

- pHIL EMERGENCEDocument1 pagepHIL EMERGENCEmavlazaro.1995No ratings yet

- Blake Critiques Society in Songs of Innocence and ExperienceDocument1 pageBlake Critiques Society in Songs of Innocence and ExperienceJarrad The-Todd AdamsNo ratings yet

- Donne's Conceptualization of Love from Physical to MetaphysicalDocument22 pagesDonne's Conceptualization of Love from Physical to Metaphysicalyumnasahar siddiquiNo ratings yet

- Problems of Language in GDocument6 pagesProblems of Language in Gapi-533561996No ratings yet

- COHENDocument2 pagesCOHENKazi RidwanNo ratings yet

- Five Paragraph EssayDocument1 pageFive Paragraph EssayKhalid IbrahimNo ratings yet

- l10 and 11 Ms Kat Poetry Appreciation GuideDocument2 pagesl10 and 11 Ms Kat Poetry Appreciation Guidejuliano gouderNo ratings yet

- Article After 450 Years, We Still Don't Know The True Value of ShakespeareDocument3 pagesArticle After 450 Years, We Still Don't Know The True Value of ShakespeareJaydenNo ratings yet

- Tennyson Echo and NarcissusDocument9 pagesTennyson Echo and NarcissusCarla Sendón GonzálezNo ratings yet

- The poetic meter of the given sonnet is iambic pentameter.Iambic pentameter refers to lines with five metrical feet, where each foot contains one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllableDocument15 pagesThe poetic meter of the given sonnet is iambic pentameter.Iambic pentameter refers to lines with five metrical feet, where each foot contains one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllableRon GruellaNo ratings yet

- Far From The Madding Crowd - TestoDocument3 pagesFar From The Madding Crowd - Testogb.bonny12No ratings yet

- By: Alisher Janassayev: Analysis of Prayer Before Birth, The Tyger and Half Past TwoDocument5 pagesBy: Alisher Janassayev: Analysis of Prayer Before Birth, The Tyger and Half Past TwoAlisher JanassayevNo ratings yet

- Mother Tongue Content for 1st QuarterDocument8 pagesMother Tongue Content for 1st QuarterRoginee Del SolNo ratings yet

- 21ST-Q4 ReviewerDocument23 pages21ST-Q4 ReviewerLearner AccNo ratings yet

- Gilgamesh, Epic Of: Martin WorthingtonDocument3 pagesGilgamesh, Epic Of: Martin WorthingtonsrdjanNo ratings yet