Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Leising Gallrein Dufner PSPB2014

Uploaded by

Haroon khanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Leising Gallrein Dufner PSPB2014

Uploaded by

Haroon khanCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/256472256

Judging the Behavior of People we Know: Objective Assessment, Confirmation of

Pre-Existing Views, or Both?

Article in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin · December 2013

DOI: 10.1177/0146167213507287

CITATIONS READS

35 329

3 authors:

Daniel Leising Anne-Marie Brigitte Gallrein

Technische Universität Dresden Technische Universität Dresden

81 PUBLICATIONS 1,717 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 76 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Michael Dufner

Universität Witten/Herdecke

62 PUBLICATIONS 2,057 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Moderators of the Effects of Narcissism on Social Outcomes View project

Social processes underlying the joint development of personality and social relationships during university studies View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Michael Dufner on 10 May 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin http://psp.sagepub.com/

Judging the Behavior of People We Know: Objective Assessment, Confirmation of Preexisting Views, or

Both?

Daniel Leising, Anne-Marie B. Gallrein and Michael Dufner

Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2014 40: 153 originally published online 9 October 2013

DOI: 10.1177/0146167213507287

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://psp.sagepub.com/content/40/2/153

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Society for Personality and Social Psychology

Additional services and information for Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://psp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://psp.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Jan 13, 2014

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Oct 9, 2013

What is This?

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

507287

research-article2013

PSPXXX10.1177/0146167213507287Personality and Social Psychology BulletinLeising et al.

Article

Personality and Social

Judging the Behavior of People We Know:

Psychology Bulletin

2014, Vol. 40(2) 153–163

© 2013 by the Society for Personality

Objective Assessment, Confirmation of and Social Psychology, Inc

Reprints and permissions:

Preexisting Views, or Both? sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0146167213507287

pspb.sagepub.com

Daniel Leising1, Anne-Marie B. Gallrein1,

and Michael Dufner2

Abstract

The present study investigates the relative extent to which judgments of people’s behavior are influenced by “truth” (as

measured by averaged observer-judgments) and by systematic bias (i.e., perceivers’ preexisting views of target persons).

Using data from online questionnaires and laboratory sessions (N = 155), we demonstrate that self- and peer-judgments of

people’s actual behavior in specific situations are somewhat accurate but are also affected by what perceivers thought of the

targets before observing their behavior. The latter effect comprises a general evaluative component (generally positive or

negative views of targets) and a content-specific component (views of targets in terms of specific characteristics, for example,

“restrained”). We also found that friends, but not targets themselves, tend to judge targets’ behaviors more positively than

unacquainted observers do. The relevance of these findings for person perception in everyday life and in research contexts

is discussed.

Keywords

behavior, judgment, accuracy, evaluation, acquaintance

Received October 30, 2012; revision accepted September 8, 2013

A real-life example: A board of assessors meets to see a According to West and Kenny’s (2011) Truth and Bias

candidate present his research, and then, based on their Model, the variables affecting all sorts of judgments, includ-

observations, decide whether the candidate should be ing judgments of persons, can be categorized as either “truth”

granted a “certificate of eligibility for tenure” (Habilitation, or “bias” variables. Truth variables represent what is “real”

specific to the academic system in some European coun- or “objectively correct” about a judgment, whereas bias vari-

tries). The meeting is public, thus many people who are not ables represent any systematic influences apart from that.

members of the board—including one of the candidate’s The extent to which a truth or bias variable affects judgments

close friends—are also part of the audience. After the talk, is called the “force” of that variable. In the present study, we

the candidate’s friend approaches some colleagues and investigate the relative extents to which self- and peer-

praises the candidate’s performance: “Now, this is how it’s judgments of people’s behavior in specific situations are

done!” and so on. It is obvious that he actually believes the affected by how the target actually behaved (truth) and by the

candidate performed really well and must have impressed preexisting views that the perceivers had of the targets before

everybody in the room quite a bit. Praising the candidate’s observing their behavior (bias).

performance for other reasons (e.g., to influence the deci-

sion that is about to be made) would make no sense for him

because the people he talks to have nothing to do with the

Truth in Judgments of Behavior

formal evaluation of the candidate. Notably, nobody agrees There are at least two distinct ways in which behavior may

with him. Most people just nod politely to what he says and be described. On the one hand, one may focus on qualities of

remain silent. Obviously, the other people in the room, who

just saw the candidate for the very first time, agree that the 1

Technical University Dresden, Germany

candidate’s performance was actually quite horrible. How 2

Humboldt-University Berlin, Germany

may such discrepant perceptions of the same person’s

Corresponding Author:

behavior be explained? May the personal relationship Daniel Leising, Department of Psychology, Technical University Dresden,

between the candidate and the friend have something to do 01062 Dresden, Germany.

with it? Email: Daniel.Leising@tu-dresden.de

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

154 Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40(2)

behavior that are measurable with great exactness (e.g., previously neglected question of whether the same is true

whether person A decreases or increases her physical dis- for behavioral judgments that are provided by close

tance from person B). Such qualities of behavior may often acquaintances of the targets.

be assessed without relying much on any subjective human

judgments (e.g., by means of a ruler). The downside of such Preexisting Views as Biases in

assessments is that their meaning is often psychologically

ambiguous, and thus needs to be interpreted a posteriori by

Judgments of Behavior

the researcher. In everyday life, on the other hand, people The systematic biases that we focus on in the present article

tend to describe their own and others’ behaviors by meaning- concern perceivers’ preexisting views of the target persons

laden terms like, for example, “friendly,” “hasty,” “hostile,” whose behavior they judge. In terms of the Truth and Bias

or “relaxed.” That is, they focus on the psychological rele- model, such preexisting views are bias variables that may

vance of people’s behavior rather than on its physical quali- affect behavioral judgments independent of the truth. There

ties. This latter kind of behavioral judgment is also the one are at least two conceptually distinct ways in which such

that we are dealing with in the present article. However, views may influence subsequent judgments of behavior, one

determining whether a perceiver’s judgment of a target’s of them being globally evaluative and the other being con-

behavior by means of a meaning-laden term reflects the tent-specific. In the first case, a perceiver may simply have

“truth” is less straightforward than in the first case. an overall positive (or negative) attitude toward a target, and

It may be argued that the best way to assess whether thus tend to use all sorts of positive (or negative) terms to

some behavior is “actually” friendly, hasty, hostile, or describe that target’s behavior in a given situation, irrespec-

relaxed is the average view that many neutral observers tive of how the target “actually” behaved. In the second case,

have of that behavior (cf. Kenny, 2004). Averaging different a perceiver may have a content-specific view of a target (e.g.,

perceivers’ judgments of the same behavior reduces the as being arrogant, witty, or aloof), and thus tend to judge that

impact of the individual perceivers’ idiosyncratic term uses target’s behavior in a given situation accordingly, irrespec-

and focuses on the common element instead. The existence of tive of how the target “actually” behaved.

the latter constitutes the very reason why person-descriptive Regarding global evaluation, there is a considerable varia-

language may be effectively used at all. Moreover, averag- tion in how positively or negatively people tend to view them-

ing judgments of behavior will yield an impression that is selves and others (cf. Bono & Judge, 2003; Furr & Funder,

more representative of how a behavior will be perceived by 1998; Kim, Schimmack, & Oishi, 2012; Leising, Erbs, &

the average other person. This in turn is important because Fritz, 2010; Nisbett & Wilson, 1977; Saucier, 1994;

how others interpret our behaviors will strongly determine Srivastava, Guglielmo, & Beer, 2010; Wood, Harms, &

the consequences of those behaviors (Leising & Müller- Vazire, 2010), and such different attitudes strongly predict

Plath, 2009), so the “social reality” that only exists in other whether perceivers will use positive or negative terms in

people’s minds at first (e.g., “the remark that Pete just made characterizing targets (Leising et al., 2010; Leising, Ostrovski,

was really offensive”) may eventually have very real effects & Zimmermann, 2013). Sometimes, a perceiver’s character-

on the target person (e.g., Pete may be asked to leave). In ization of a target’s behavior in a given situation may even

accordance with this view, we define accuracy as the agree- depend more on whether the perceiver is fond of the target or

ment between a given perceiver’s judgment of a given not than on how the target “actually” behaved. We are talking

behavior and the average judgment of the same behavior by about partisanship here. Research in social psychology has

several neutral observers. In terms of West and Kenny’s demonstrated that perceptions of behavior may be strongly

(2011) Truth and Bias model, the truth variable in our study affected by a perceiver’s loyalty or allegiance regarding the

is the average behavior judgment by several neutral observ- target person: Studies of presidential debates in the United

ers, and the extent to which this variable predicts judgments States showed that this factor predicted which candidate

of the same behavior by any other perceivers (e.g., targets viewers would see as the winner (cf. Munro et al., 2002). In

or informants, see below) is the “force” of the truth the present study, we expect that a perceiver who already

variable. holds a generalized positive image of a target person will see

Using such a definition, research has shown that indi- the subsequent behaviors of that target person in a more posi-

viduals are in fact able to judge their own behavior within tive light, whereas a perceiver with a more negative attitude

specific situations with some degree of accuracy (e.g., toward a target will do the opposite. We apply this logic to

Leising, 2011; Sadler & Woody, 2003). In these studies, self- and peer-judgments of behavior alike.

participants were asked to judge their own behavior during Apart from global evaluation, a perceiver may think that a

laboratory interactions, and these self-ratings did predict person’s behavior in a given situation was highly (for exam-

judgments of the same interactions by unacquainted observ- ple) sophisticated, friendly, or arrogant because he or she

ers. Therefore, we expect that in the present study, self- tended to think of the target as being sophisticated, friendly,

judgments of behavior will converge at least somewhat or arrogant even before actually observing the behavior in

with judgments by neutral observers. We also address the question. Note that here it is the specific content of the word,

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

Leising et al. 155

not its evaluative connotation, that matters. Let us consider, own behavior (Leising, 2011), or the personality assessment

for example, a perceiver who is supposed to judge a known took place shortly after the participants had judged their

target’s “quickness” at a problem-solving task. Regardless of own behavior (Sadler & Woody, 2003). In the present study,

how positively or negatively the perceiver thinks of the tar- we use much longer intervals between the two kinds of

get in general, if she is convinced that the target is usually assessment in order to rule out this alternative explanation.

“quick” at accomplishing things, she may tend to judge the Finally, our study extends the previous work by testing

quickness of the target’s problem solving in the situation whether the preexisting views affect not only self- but also

accordingly, regardless of how quick the target actually was. peer-judgments of behavior.

There is some evidence supporting the notion that people

tend to characterize the behaviors of targets in line with pre-

existing images, and that to some extent, this happens inde-

Possible Mechanisms

pendent of the targets’ actual behaviors. For example, in the Even though we do not directly address psychological mecha-

study by Sadler and Woody (2003), the participants tended to nisms in the present article, we think it should still be asked

rate their own behavior during an interpersonal interaction in why one may expect effects of perceivers’ preexisting views

accordance with their general self-views, even if their “actual” of targets on those perceivers’ subsequent judgments of the

behavior during the interaction (as consensually judged by same targets’ behaviors. Would it not be more reasonable for

several observers) was controlled for. In other words, the par- a perceiver to form as accurate an impression of the target’s

ticipants overestimated the extent to which their behavior in behavior as possible and not rely on any other source of infor-

the situation concurred with what they generally thought of mation than “what is actually there” (truth)? A large number

themselves. Sadler and Woody (2003) called this phenome- of studies have demonstrated that people tend to interpret new

non a “consistency bias” (cf. Leising, 2011). information in accordance with their preexisting beliefs or

In the present article, we will use the term preexisting expectations (see Nickerson, 1998, for a review). This phe-

views (PEV) to denote the images of the targets that already nomenon has often been attributed to motivational factors

existed in the perceivers’ minds before they engage in the such as a basic need to maintain cognitive congruence

task of judging the targets’ behavior in specific situations. An (Festinger, 1957; Kunda, 1990; Nickerson, 1998). It may be

important limitation of the aforementioned studies is that argued that such congruence is needed because only congru-

they did not distinguish between preexisting views that are ent views permit predictions of future events. With regard to

globally evaluative and preexisting views that are content- behavior perception, this would imply that once a perceiver

specific. Thus, for example, a given perceiver’s judging a has formed a certain view of a target person, he or she may be

target’s personality and behavior as “witty” may have been inclined to actively seek or prioritize novel information that

due to the specific content of the term or simply due to the concurs with this view. In fact, research has shown that once

fact that the term has a positive evaluative connotation. In the individuals have developed some belief about another person

present study, we disentangle these two possibilities from (e.g. “the person is friendly”), they selectively seek behav-

one another by separately investigating the influences of pre- ioral evidence that confirms rather than falsifies this belief

existing views that are globally evaluative (PEV-GE) and (Lord, Lepper, & Preston, 1984; Snyder & Campbell, 1980;

preexisting views that are content-specific (PEV-CS). Snyder & Swann, 1978).

Moreover, we also disentangle two components of behav- Another possible explanation is more informational in

ioral judgments that were not disentangled in previous stud- nature. For a perceiver who has access to several sources of

ies of the “consistency bias”: Preexisting views of targets information about a target (e.g., observations of the target’s

may affect subsequent judgments of those targets’ behaviors behavior in several situations), it may be wise to pool that

because (a) perceivers judge particular targets in certain information in order to form the most accurate impression of

ways and/or because (b) perceivers tend to judge all targets the target possible. The upside of doing so would be that the

in certain ways. In Kenny’s (1994) terminology, the former resulting image of the person would likely become more rep-

would be denoted as “relationship effects,” whereas the latter resentative of how the person is on average, possibly permit-

would be denoted as “perceiver effects.” We investigate how ting more accurate predictions of the target’s behavior in the

strongly both components contribute to the consistency long run. Thus, if the target’s behavior in a new situation

between preexisting views and subsequent judgments of deviates from what the perceiver has previously learned

behavior. about the person, the new information may be partially dis-

Furthermore, in the studies described above the interval counted as an “exception,” and the interpretation of the new

between the global self-assessment of personality and the behavior may be “colored” by the perceiver’s previous expe-

momentary self-assessment of situated behavior was very riences with the target. The downside of doing so, however,

short (less than an hour). It is thus conceivable that the influ- would be that the perceiver’s ability to judge the target’s

ence of the perceivers’ preexisting views was overestimated behavior in just one situation objectively may at least partly

because the participants’ general images of themselves were be compromised. The present study investigates the extent to

made salient shortly before they were asked to judge their which this is the case.

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

156 Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40(2)

Overview of the Present Study Procedure

Given the ubiquity and importance of self- and peer-judg- Recruitment. We advertised the study on a campus website

ments of behavior in everyday life as well as in psychologi- and in local community centers. The announcement of the

cal research, it seems worthwhile to examine the factors that study contained an e-mail address to which participants were

contribute to the formation of such judgments. In the present asked to write in order to register for the study. When pro-

study, we use a design that allows us to simultaneously spective participants contacted the research team, they

investigate the influence of truth and bias (i.e., perceivers’ received an e-mail containing some broad information

preexisting view of targets) on self- and peer-judgments of regarding the aims and procedures of the study. The e-mail

behavior. In order to maximize external validity (cf. also asked the participants to recruit a second person who

Baumeister, Vohs, & Funder, 2007), we do not use written knew them reasonably well and would also be willing to take

vignettes of people’s behavior (which was the predominant part in the study. When a prospective participant contacted

method in previous studies addressing similar issues) but the research team again and named a second person who had

rather investigate judgments of people’s actual behaviors. agreed to participate, we randomly determined which of the

Specifically, we invite target persons and their peers to the two persons would serve as the target and which would serve

laboratory and then videotape the targets’ behaviors in a vari- as the informant. In the following, we will call these target-

ety of standardized situations. Afterward, the targets and informant pairs dyads.

their peers judge the targets’ behaviors. In order to obtain an

accuracy criterion, the same behaviors are also judged by Personality questionnaires. Both the target and the informant

unacquainted observers. The general images that the targets of a dyad received an e-mail containing a link to an online

and their peers have of the targets’ personalities are assessed questionnaire. They were asked to log in and describe the

by means of online questionnaires several days prior to the target person’s personality by means of an adjective list (see

laboratory assessments. The design enables us to compare below). We emphasized that the two persons should com-

the relative influence of the truth (= averaged observer-judg- plete the questionnaire independently and that they should

ments), as compared to PEV-GE and PEV-CS, on the partici- not communicate with each other about their ratings. The

pants’ judgments of their own and their peers’ behaviors. online questionnaire also contained a number of questions

regarding the two participants’ personal backgrounds (e.g.,

socioeconomic status) and their relationship with each other

Method (e.g., knowing and liking).

Sample Laboratory session. A few days later, the target and the infor-

The main sample comprised two groups of participants, the mant were invited to come to the lab together for a series of

target persons (N = 155) and the informants (N = 155), who observational assessments. These assessments all took place

came to the lab together in dyads (see below). Each partici- on the same day and comprised three stages. In the first stage,

pant (i.e., target or informant) received 15 Euros as a reward the target person engaged in four tasks, which were presented

for participating. One hundred and fifty target persons com- in random order. Task 1 consisted of answering a number of

pleted the online questionnaire. Of these, 86 were female, 63 questions pertaining to general knowledge (e.g., “How high

were male, and 1 did not report sex. The mean age of the is Mount Everest?” “How many people live in the Tokyo

targets was 23.2 years (SD = 4.06). Of the informants, 153 area?” “Who wrote the opera ‘Fidelio’?”). Task 2 consisted

completed the online questionnaire. Of these, 93 were of a role-play in which the target person was to call a “neigh-

female, 59 were male, and 1 did not report sex. The mean age bor” (actually played by a confederate) and to demand that

of the informants was 23.8 years (SD = 4.44). The majority the neighbor turns down the volume on her stereo (cf. Borke-

(n = 85) of the informants were friends of the targets’. nau, Mauer, Riemann, Spinath, & Angleitner, 2004). In Task

Another large proportion of the informants were the targets’ 3, the target person was asked to spontaneously tell a brief

romantic partners (n = 53). Other kinds of relationships story incorporating the terms “Corkscrew,” “Holiday,”

between informants and partners (e.g., colleagues, siblings) “Catastrophe,” and “Glove Box.” In Task 4, the target person

were less frequent (n < 10). The informants reported know- was asked to (a) sing a song of his or her own choice, (b) tell

ing the targets quite well (M = 4.17, SD = 0.79, on a scale a joke of his or her own choice, and (c) pantomime the term

ranging from 1 [“not at all”] to 5 [“very well”]) and liking party (which in German does not also mean “political party”

them very much (M = 4.70, SD = 0.51, on a scale ranging but only “festivity”). The four tasks were selected to enable

from 1 [“not at all”] to 5 [“very much”]). The values for the an assessment of diverse qualities of behavior. Completing a

targets’ knowing and liking of the informants were virtually task usually took a target less than 90 s. The targets’ behavior

identical (Knowing: M = 4.21, SD = 0.73; Liking: M = 4.67, while engaging in the tasks was videotaped. While the target

SD = 0.55), which is unsurprising given that the roles of tar- of a given dyad completed the four tasks, the respective

get and informant were assigned at random (see below). informant was seated in another room and asked to wait.

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

Leising et al. 157

In the second stage of the laboratory session, the target and more stable behavioral dispositions (in the online personality

the informant each rated four video-clips, by means of the questionnaire) and their more transient situation-bound behav-

same adjective list that was also used for the personality iors (in the lab). This conforms to the personality states

assessments (see below). These video-ratings took place in approach, which posits that both traits and states may be

separate rooms. One member of the dyad (the target or the assessed by means of the same vocabulary (Fleeson, 2001;

informant) rated the video-clips that had just been produced— Bleidorn, 2009). For example, in the online questionnaire, the

the ones showing the current target engage in the four tasks. targets and their informants rated how “shy” or “egoistic” they

The tasks were presented in the same order in which the target considered the targets to be in general, whereas in the lab ses-

had completed them. Meanwhile, the other member of the sion, they rated how “shy” or “egoistic” they considered the

dyad watched four video-clips showing the target of the pre- targets’ behavior during the tasks to be. However, because fac-

vious dyad (i.e., an unknown person) engage in the same tor structures of measures may differ considerably depending

tasks. Both the target and the informant of the current dyad on whether a measure is used for assessing states versus traits

were asked to watch one of the respective video-clips that had (e.g., Leising & Bleidorn, 2011), we only report analyses at

been assigned to them, then rate the respective target’s behav- the level of individual items in the following. This is also the

ior by means of the adjectives, then watch the next video-clip, level of abstraction at which everyday communication about

and so on. Whether the informant watched the current target individual differences in personality and behavior takes place.

and the current target watched the previous target, or vice The intervals between the completion of the online question-

versa, was also determined at random. naire and the laboratory assessments had an average length of

In the third stage of the laboratory session, the previous M = 4.08 days (SD = 3.24) for the targets and of M = 4.43 days

rating assignments were reversed: If the informant had just (SD = 4.37) for the informants.

rated the current target, and the current target had just rated Each of the 30 adjectives was also rated in terms of how

the previous target, then the informant was now supposed to positive or negative an impression of a target person it evokes

rate the previous target, whereas the current target was sup- (i.e., social desirability). For this, we used the ratings that

posed to rate himself or herself. If the rating assignments in were provided by 24 student raters as part of the study by

the second stage had been the other way round, then the Leising et al. (2010). The scale ranged from 1 (very negative)

assignments in the third stage were reversed accordingly. to 7 (very positive). Interrater reliability for these ratings was

This way, we let both the informants and the targets judge (a) ICC(3, 24) = .98. The desirability ratings were needed to

targets they knew and (b) targets they did not know. compute global evaluation indices by correlating a perceiv-

er’s ratings of a target on the 30 items with the profile of item

External observers’ ratings. Each of the 620 video-clips (= 155 desirabilities (Edwards, 1953). The resulting correlations

targets × 4 tasks) was also independently rated by at least reflect the extent to which the perceiver describes the target

three observers who were unacquainted with the targets (the in a more positive or negative manner overall.

maximum number of observers per video was six). The over-

all pool of observers comprised 18 persons from which sub-

groups were selected randomly to judge the individual Results

video-clips. The ratings were balanced such that each observer Agreement Between the Observers

would get to see all targets but only see each target in one

randomly chosen situation. Hence, the observer-ratings We used averaged observer-ratings as a measure of the tar-

always reflected judgments by persons who saw the respec- gets’ “true” behaviors during the laboratory tasks. The aver-

tive target in just one situation. The observers did not receive age interrater agreement, ICC(1, 3), between three observers

any training (apart from general technical instructions on how in judging the targets’ behavior by means of a single item

to watch the videos and provide their ratings) in order to pre- was .45 (SD = 0.15) for the story task, .47 (SD = 0.19) for the

serve the representativeness of their intuitive ways of apply- pantomime task, .44 (SD = 0.18) for the role-play task, and

ing the adjectives to the target persons’ behaviors. .49 (SD = 0.11) for the knowledge task. These levels of inter-

rater agreement are comparable to the levels of agreement

that were obtained in previous studies (e.g., Borkenau et al.,

Measure 2004) and can be regarded as quite satisfactory. Note that

The adjective list that we employed for the ratings of the tar- they reflect lower-bound estimates for interrater agreement

gets’ personalities and behavior in the lab was devised by because the performances of most targets in most situations

Borkenau and Ostendorf (1998) and has been used in several were judged by more than three observers.

person perception studies (e.g., Leising et al., 2010; Leising et

al., 2013). It consists of 30 terms that assess the Big Five per-

Correlations Among the Predictors

sonality factors by six items each. Three terms for each factor

have a positive valence and three have a negative valence. We In West and Kenny’s (2011) Truth and Bias Model, the truth

let the participants use the same terms for assessing the targets’ and bias variables may or may not be correlated with one

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

158 Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40(2)

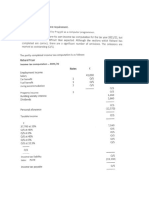

Table 1. Prediction of the Targets’ and the Informants’ Behavior Ratings From the Truth and the Two Bias Variables.

Standardized Betas

Without

Criterion Predictor Betas Raw perceiver effects

Behavior rating by target Truth .22 (.16, .28) .14 (.10, .18) .17 (.13, .21)

PEV-CS bias .18 (.14, .22) .17 (.13, .21) .13 (.10, .15)

PEV-GE bias .28 (.21, .35) .09 (.06, .11) .03 (.00, .05)

Behavior rating by Truth .31 (.23, .38) .18 (.13, .23) .18 (.15, .22)

informant PEV-CS bias .21 (.17, .25) .19 (.15, .23) .08 (.05, .11)

PEV-GE bias .22 (.13, .30) .08 (.04, .10) .04 (.02, .06)

Note. Coefficients were first computed for each task and item separately and then averaged (99% bootstrap confidence intervals are in parentheses).

Truth = averaged observer-ratings of the targets’ behavior, PEV-CS = Perceivers’ preexisting views of targets (content-specific) as measured by the

perceivers’ response to the same item in the personality questionnaire. PEV-GE = Perceivers’ preexisting views of targets (global evaluation) as measured

by the correlation between the perceiver’s description of the target in the personality questionnaire and the social desirabilities of the 30 items. PEV-GE

was multiplied with minus 1 when predicting behavior ratings on items with a negative valence (average desirability rating < 4).

another. In our sample, all correlations between the three pre- preexisting views of the targets in terms of particular items

dictors (averaged across items) were statistically significant (PEV-CS), and (c) the same perceivers’ preexisting global

as indicated by 99% bootstrap confidence intervals that did evaluations of the targets (PEV-GE). For these analyses, we

not include zero. The targets’ self-ratings on an individual used the targets’ and the informants’ ratings of persons they

questionnaire item (PEV-CS) predicted the observers’ ratings knew (i.e., the current targets) because without prior acquain-

of the targets’ behavior on the same item (truth) at r = .14 on tance between target and perceiver, behavior judgments

average. The respective correlation for the informants’ ratings could not be affected by the latter two factors. Note that by

of the targets’ personalities was r = .11. Thus, the targets’ and using multiple regressions, we determined the independent

the informants’ item-specific views of the targets’ personali- contributions of each predictor, controlling for the other two

ties had some validity, in that they could predict independent predictors.

ratings of the targets’ behaviors in the lab later on. Table 1 displays the average Betas that emerged for the

Before computing the average correlation of PEV-GE three predictors, along with 99% confidence intervals that

with PEV-CS and with the observer-ratings of the targets’ were determined by bootstrapping with the 30 items as cases.

behavior, PEV-GE had to be inverted (i.e., multiplied with To arrive at these correlations, we first ran multiple regres-

−1) in all cases where it was correlated with an item that had sions for each item and task separately (= 120 regressions),

a negative valence (i.e., an average desirability rating < 4). then averaged the resulting coefficients across tasks for each

Otherwise, the correlations of PEV-GE with positive and item (distinguishing between tasks did not lead to any differ-

negative items might have canceled out when averaging ent conclusions), and then averaged across the 30 items. In

across items. After implementing this rule, the average cor- computing average Betas for PEV-GE, we again reversed the

relation between PEV-GE and PEV-CS was .28 for the tar- direction of the predictor for all items with a negative

gets’ self-ratings and .34 for the informant-ratings, suggesting valence. Otherwise, positive and negative associations might

that targets who received more positive overall personality have canceled out. In fact, when not inverting PEV-GE in

ratings were also judged more positively on individual items. predictions of negative items, the average standardized Betas

The averaged observer-ratings of the targets’ behavior (truth) for the individual items correlated at r(28) = .94 (targets) and

correlated at .06 (on average) with PEV-GE in the targets’ r(28) = .87 (informants) with the items’ social desirability

self-ratings of their personalities and also at .06 with PEV-GE ratings. Thus, the more an item entailed a positive or nega-

in the respective informant-ratings. Thus, targets who had tive evaluation, the better the perceivers’ ratings of the tar-

received more positive overall personality ratings were also gets’ behavior by means of that item could be predicted from

judged in a slightly more positive manner by the average the same perceivers’ preexisting global evaluations of the

observer, on individual items. targets (PEV-GE).

In our discussion of the average contributions of the three

Relative Influence of Truth and Bias on predictors, we will concentrate on the standardized Betas

that are displayed in the second and third data column of

Judgments of the Behavior of Known Targets Table 1. As can be seen from the entries in the second data

Using multiple regressions, we predicted the participants’ column, all three predictors made significant contributions in

(i.e., the targets’ and the informants’) judgments of the tar- predicting the targets’ and the informants’ judgments of the

gets’ behavior in the lab from (a) averaged observer-judg- targets’ behavior: The targets’ actual behavior (truth)—as

ments of the same behavior (truth), (b) the same perceivers’ judged by unacquainted observers—and the perceivers’

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

Leising et al. 159

content-specific preexisting views of the targets (PEV-CS) with a target impairs validity, then accuracy should be lower

both made significant contributions of approximately the for “a” and “b” as compared to “c” and “d.”

same size. In addition, the perceivers’ globally evaluative First, we computed the correlations between each of the

views of the targets (PEV-GE) made another significant, but four perspectives and the averaged observer-ratings sepa-

somewhat smaller, contribution of their own. The relative rately for each task and item. Then we averaged across tasks.

strengths of the three effects were approximately the same Across the 30 items, the mean correlation was r = .18 (99%

for self- and informant-ratings of behavior. bootstrap CI = [.13, .22]) for the current targets’ ratings of

We also controlled for perceiver effects in order to deter- their own behavior (a), r = .22 (CI = [.17, .27]) for the current

mine how much of the influence of the two bias variables informants’ ratings of the current targets’ behavior (b), r =

was due to general perceptual tendencies as opposed to the .26 (CI = [.22, .30]) for the current targets’ ratings of the

perceivers’ views of the particular targets at hand. In the previous targets’ behavior (c), and r = .21 (CI = [.16, .26]) for

present study, a perceiver’s perceiver-effect was obtained by the current informants’ ratings of the previous targets’ behav-

averaging his or her judgments of the behavior of the known ior (d). Confidence intervals revealed that only the greatest

target (i.e., himself or herself or the other person in his or her difference (.18 vs. .26) was significant, suggesting that the

dyad) and the unknown target (i.e., the target of the previous accuracy of the targets’ judgments was greater when they

dyad). Perceiver-effects were calculated separately for each judged someone else’s behavior as compared to when they

of the 30 items and subtracted from the participants’ ratings judged their own behavior.

of the targets’ behavior (i.e., the DV) before repeating the

item-wise multiple regressions described above. The results

are displayed in the third data column of Table 1: Controlling

Global Evaluation Across Different Assessments

for perceiver effects did not change the effect size for the Finally, we compared how positively or negatively partici-

truth variable (i.e., observer-ratings of the targets’ behav- pants’ personalities and behaviors were judged by the dif-

ior). It did, however, significantly reduce the influence of the ferent types of perceivers. In each case, a perceiver’s overall

perceivers’ global evaluations of the targets (PEV-GE) on evaluation of a target was measured in terms of the within-

both self- and informant-ratings of behavior. Thus, a substan- person correlation between the perceiver’s description of

tial proportion of the above-reported effect of this predictor the target across the 30 adjectives and the social desirability

was due to perceiver effects. For self-ratings, the respective ratings for these adjectives. Thus, a positive correlation was

confidence interval almost included zero (the lower confi- indicative of positive global evaluation. Note that global

dence limit was minimally larger than zero, which is obscured evaluation coefficients were computed for the participants’

in the table because of rounding). Finally, controlling for per- judgments of the targets’ personalities by means of the

ceiver effects also lowered the impact of PEV-CS on behav- online questionnaire (= PEV-GE) as well as for their judg-

ior judgments, with the decrease being considerably stronger ments of the targets’ behavior in the lab. Each target’s

for the informants’ (compared to the targets’) judgments of behavior in the lab was rated by one previously acquainted

the targets’ behavior. target (i.e., the target’s self-rating) and one previously

acquainted informant, as well as by one unacquainted target

Loss of Validity Due to Target-Perceiver and one unacquainted informant. In addition, there were

three to six observer-ratings of each target’s behavior. In

Relationship? order to ensure comparability between perspectives, we

Given that the perceiver’s preexisting views of the targets first computed a global evaluation index for each individual

were found to affect their subsequent judgments of the tar- observer and then averaged across observers. For behavior

gets’ behavior, we investigated whether the accuracy of judg- ratings, evaluation indices were first computed separately

ments of known targets was lower than the accuracy of for each task and then averaged across tasks.

judgments of unknown targets. To this aim, we compared the The average global evaluation indices were r = .58 (range

accuracy of four kinds of judgments with each other: (a) The = −.14 to .92) for the targets’ self-descriptions and r = .68

targets’ judgments of their own behavior, (b) the informants’ (range = .05 to .93) for the informants’ descriptions of “their”

judgments of the behavior of “their” targets, (c) the targets’ targets’ personalities in the online questionnaire. The targets’

judgments of the behavior of the previous targets, and (d) the average evaluation was r = .43 (range = −.62 to .88) for their

informants’ judgments of the behavior of the previous tar- own behavior in the lab and r = .45 (range = −.36 to .89) for

gets. Thus, we compared the accuracy of perceivers who other targets’ behavior. The informants’ average evaluation

judged targets they already knew (a, b) with the accuracy of was r = .54 (range = −.48 to .93) for their “own” targets’

perceivers who judged targets they did not know (c, d). In all behavior in the lab and r = .40 (range = −.41 to .88) for other

four cases, accuracy was defined as the agreement between targets’ behavior. Finally, the average evaluation of the tar-

the respective kind of judgment (a, b, c, d) and the average gets’ behavior in the lab by a single neutral observer was r =

observer-judgment of the same behavior. If acquaintance .41 (range = −.31 to .77).

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

160 Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40(2)

We first compared the evaluation coefficients for the five informant-ratings of a person’s behavior are at least partly

different kinds of judgments of the targets’ behavior in the accurate or valid.

lab with one another, using one-way repeated measures Apart from that, however, the present article also demon-

ANOVA. The comparison was statistically significant, F(4, strates that people’s judgments of the behavior of targets they

147) = 12.274, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons with know are affected by two different kinds of bias: evaluative

Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing (α = .01) sug- and content-specific preexisting views of a person. The for-

gested that the informants’ judgments of their own targets’ mer bias closely resembles the effect of partisanship on judg-

behavior were significantly more positive than all other ments of candidates’ performances in presidential debates

behavior judgments but that none of the other behavior judg- (cf. Munro et al., 2002). However, the findings of the present

ments differed from each other in terms of global evaluation. study pertain more directly to everyday interpersonal rela-

In a second analysis, we compared the evaluation coeffi- tionships: Preexisting positive or negative attitudes do not

cients for the targets’ versus the informants’ judgments only affect people’s judgments of the debate performances of

(Factor 1) and for questionnaire versus behavior ratings presidential candidates they (dis-)like, they also affect peo-

(Factor 2) with one another, using two-way repeated mea- ple’s judgments of their own behavior, and of the behavior of

sures ANOVA. Note that in this analysis, we only used judg- their close acquaintances, across diverse situations.

ments within the same dyads, that is, judgments of known Notably, the strength of the PEV-GE bias is strongly mod-

targets. The analysis yielded significant effects for both fac- erated by the evaluative connotation of the item that is used

tors, target-informant, F(1, 146) = 29.009, p < .001; behav- to describe the behavior. The more evaluative the item is, the

ior-personality, F(1, 146) = 94.784, p < .001; but no larger the (positive or negative) impact of the perceiver’s

significant interaction effect, F(1, 146) = 0.215, p = .643. global evaluation of the target will be (cf. Leising &

Hence, informants viewed targets more positively than tar- Borkenau, 2011). The present study is already the third to

gets viewed themselves, and for both targets and observers, empirically corroborate this interaction between perceivers’

ratings of overall personality were more positive than ratings global evaluations of targets (sometimes assessed as “lik-

of behavior in the lab. ing”) and the evaluativeness of person descriptors (cf.

Leising et al., 2010; Leising et al., 2013). In fact, the correla-

tions that we found between the Betas for PEV-GE and the

Discussion item desirability ratings were so high (r > .86) that it may be

reasonable to interpret the latter as directly reflecting the

Truth and Bias in Judgments of Behavior

extent to which items will respond to a perceiver’s more pos-

The current study aimed to investigate the relative extents to itive or negative attitude toward a target. This renders it

which self- and informant-ratings of targets’ behavior in spe- likely that controlling for item desirability may be an effec-

cific situations reflect “the truth,” as opposed to two different tive way of addressing socially (un-) desirable responding

kinds of bias (i.e., PEV-GE and PEV-CS). Taken together, we (cf. Paulhus, 2002), that is, individual differences between

found that the truth and both bias variables had significant and perceivers in terms of their judging (all or particular) targets

independent effects on self- and informant-ratings of behavior. too positively or too negatively. Future research needs to

To some extent, such ratings reflect (a) the views that external address this highly intriguing possibility.

observers would have of the same behaviors (truth), (b) the The other kind of bias that independently affects behavior

generally positive or negative views that the perceivers had of judgments is content-specific: If a perceiver has come to

the targets before observing their behaviors (PEV-GE), and (c) generally attribute some level of a particular characteristic to

the views that the perceivers had of the targets before observ- a target person, then his or her judgments of that target’s sub-

ing their behaviors in terms of specific judgment dimensions sequent behavior in specific situations will partly reflect this

(e.g., “restrained”; PEV-CS). The “forces” of the truth and general view, even when controlling for the target’s “actual”

PEV-CS variables were about equally strong and stronger than behavior in the situation. This finding clearly stands in line

the force of the PEV-GE variable. with the previous research (cf. Leising, 2011; Sadler &

With regard to truth, we found that self- and informant- Woody, 2003). Going beyond previous findings, however,

ratings of behavior moderately agreed with average judg- the present study demonstrates that this bias effect still holds

ments of the same behavior by three or more observers. This if one controls for general evaluation. It is also the first study

largely confirms the findings of previous studies (Leising, to show that informant-ratings of behavior are just as suscep-

2011; Sadler & Woody, 2003) and implies that momentary tible to this bias as are self-ratings. Moreover, our study dem-

self- and informant-ratings of behavior do in fact concur to onstrates that a substantial proportion of the effect of PEV-CS

some extent with how the same behavior would be inter- is target-specific and cannot merely be explained in terms of

preted by persons who see the target person for the first time. perceivers’ general judgment tendencies (cf. Kenny, 1994).

If one accepts averaged behavior ratings by several neutral Finally, the present study demonstrates that the effect occurs

observers as a valid measure of the behavior’s “true” mean- even if the interval between the assessment of the perceiver’s

ing, then this finding supports the notion that self- and general image of the target and same perceiver’s judgment of

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

Leising et al. 161

the same target’s behavior in a particular situation is several that the informants’ judgments of “their” targets’ behavior in

days long (about 4 days on average). Therefore, it appears the lab were more positive than any other judgments of that

highly unlikely that the effect is merely rooted in the research- behavior. This clearly supports the notion of a “pal-serving

ers’ making the perceivers’ general images of the targets bias” (Leising et al., 2010), that is, partisanship in judgments

salient shortly before the behavioral assessment takes place. of the behavior of others we know and like. It should be

An explanation in terms of motivational or informational noted that this finding concerns a main effect (people in gen-

mechanisms (see above) seems more viable. Future research eral are partisan to their friends), whereas the above-

should compare the validities of such theoretical explana- described effects of PEV-GE concern individual differences

tions with one another. (people who generally see their targets more positively will

describe those targets’ subsequent behaviors more posi-

Loss of Validity Due to Acquaintance Between tively). It should also be noted that we did not find evidence

for a general self-serving bias in judgments of behavior. One

Target and Perceiver? possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that prais-

We also investigated whether judgments of the behavior of ing others is less “taboo” than praising oneself (cf. Gallrein,

known targets are less accurate than judgments of the behav- Carlson, Holstein, & Leising, 2013).

ior of unknown targets. Using averaged observer-ratings as Second, we found that judgments of personality were

an accuracy criterion, we found that the targets were in fact more positive than judgments of behavior in the lab. This

systematically less accurate in judging their own behavior as may be explained by our tasks eliciting behaviors that were

compared to how accurate they were in judging the behavior actually less “positive” than the behaviors that most people

of other people they did not know. However, it may not be tend to show in their everyday lives (the latter constituting

concluded that self-judgments of behavior are generally less the basis for personality judgments). Alternatively, it may be

accurate than are other-ratings because we did not find sig- the case that judgments of behavior from video are more

nificant differences in accuracy between self-ratings and data-driven than broad retrospective judgments of personal-

informant-ratings of behavior. Also, the informants were ity in a questionnaire. Because the latter kind of judgment is

about equally accurate in judging the behavior of known tar- more abstract, it may permit more target-serving, selective

gets and unknown targets. Therefore, the present study does recall of relevant behavioral episodes.

not suggest that prior acquaintance between perceivers and

targets is always detrimental to the perceivers’ accuracy in

Broader Implications and Outlook

judging the targets’ behavior. According to our view, the

finding that the targets were more accurate in judging some- Which implications do the present results have for behav-

one else than in judging themselves may be attributed to the ioral assessment in general? Most importantly, they suggest

operation of self-protective mechanisms in self-judgments that, apart from “truth,” momentary self- and other-judg-

(e.g., Tice, 1991) as opposed to the targets’ heightened atten- ments of behavior reflect a substantial proportion of system-

tion to someone else’s performance in the same situations atic bias variance. If a target’s behavior is judged by someone

that they had just undergone themselves. who is previously acquainted with the target, the resulting

It should be noted, however, that the targets and the infor- judgments will partly reflect the perceiver’s preexisting view

mants in the present study judged the targets’ behavior of the target, both in terms of general evaluation and in terms

directly after seeing them on video. This probably made it of the specific judgment dimension at hand. In other words,

relatively easy for them to be accurate because they received if we know how a perceiver generally views a target, we will

the exact same behavioral information on which the observ- be able to partly predict that perceiver’s judgments of that

ers also based their judgments. The fact that, even under such target’s subsequent behaviors, irrespective of how the target

optimal conditions for accuracy, we still found significant actually behaves. This might explain some of the stunning

effects for our bias variables (see above) renders these effects discrepancies that sometimes exist between different per-

even more impressive. We suspect that, under conditions ceivers’ views on the same targets’ behaviors (e.g., in our

where the interval between the observation and the judgment introductory real-life example).

of behavior is larger, the impact of the perceivers’ preexisting The bias effects that we found may become a problem

views of the targets on their judgments of the targets’ behav- especially when multiple momentary assessments of behav-

ior might become even stronger and possibly come to impair ior are averaged (as is often the case in experience sampling

accuracy. This issue needs to be addressed by future research. studies). For example, if we assume that people’s self-images

are relatively stable over time, they might be expected to

affect all momentary self-assessments of behavior in a simi-

Global Evaluation Across Perspectives lar manner. In contrast, the targets’ actual behaviors in the

We also investigated mean differences in how positively or different situations may contribute less to the average of

negatively the targets’ behaviors and personalities were momentary self-assessments, to the extent that they vary

described across the various assessments. First, we found over time. Taken to the extreme, it would be conceivable that

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

162 Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40(2)

an average of many momentary self-assessments may only more negative self-images (e.g., people with elevated levels

reflect the target’s overall self-images, but none of the tar- of depression). With such a sample, we would expect global

get’s actual behaviors in specific situations anymore, because evaluation to play an even more prominent role in predicting

the latter have averaged out. In such a case, the momentary the targets’ judgments of their own behaviors. When infor-

assessments would become superfluous because a single mant-ratings are used, a more realistic estimate of the global

overall self-assessment would do the job (of assessing what evaluation effect may be obtained by also recruiting infor-

people think of themselves) just as well. As the current study mants who have no particular loyalties toward, or who even

shows, using informant-instead of self-judgments of behav- dislike, their respective target persons. Such recruitment may

ior would not be a solution to this problem because infor- be challenging, but would clearly be worthwhile at the same

mant-judgments are just as prone to being biased by time, because the resulting samples of targets and perceivers

preexisting views as are self-judgments. The question of how would reflect the interpersonal world we inhabit (comprising

much incremental validity (e.g., in predicting important out- friends and foes, allies and competitors, love interests, loved

comes) aggregated momentary self- or informant-judgments ones and “exes”) more accurately.

of behavior actually have beyond the respective perceivers’

general images of the targets remains to be answered by Declaration of Conflicting Interests

future research. The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect

The present study also shows that people tend to judge the to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

behavior of their friends, but not their own behavior, in

overly positive ways. It seems appropriate to use the term Funding

overly here because we could show that these judgments

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support

were significantly more positive than judgments of the very for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This

same behaviors, by means of the very same terms, by any- research was supported by a grant (LE 2151/4-1) to Daniel Leising

body else, including neutral observers. The finding is in line provided by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

with previous research showing that people tend to view

their close acquaintances more positively than they view References

themselves (Barelds & Dijkstra, 2009; Leising et al., 2010;

Barelds, D. P. H., & Dijkstra, P. (2009). Positive illusions about

McNulty, O’Mara, & Karney, 2008; Murray, 1999; Murray,

a partner’s physical attractiveness and relationship quality.

Holmes, & Griffin, 1996; Swami, Stieger, Haubner, Voracek, Personal Relationships, 16, 263-283. doi:10.1111/j.1475-

& Furnham, 2009) but—according to our knowledge—the 6811.2009.01222.x

present study is the first study to actually demonstrate that Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Funder, D. C. (2007). Psychology

informant-ratings of behavior deviate positively from inde- as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever

pendent assessments of “the truth.” happened to actual behavior? Perspectives on Psychological

This has several important implications for person assess- Science, 2, 396-403. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00051.x

ments in real life: For targets, systematically befriending Bleidorn, W. (2009). Linking personality states, current social roles

people who might be asked to judge their behavior later on and major life goals. European Journal of Personality, 23, 509-

(e.g., as members of the board during job applications or as 530. doi:10.1002/per.731

reviewers for scientific journals) is likely to pay off in terms Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Core self-evaluations: A review

of the trait and its role in job satisfaction and job performance.

of obtaining better evaluations. Institutions (e.g., employers,

European Journal of Personality, 17, 5-18. doi:10.1002/

scientific journals) that are interested in assessing targets’ per.481

performances objectively, however, should take care that no Borkenau, P., Mauer, N., Riemann, R., Spinath, F. M., & Angleitner,

particularly positive or negative personal relationships exist A. (2004). Thin slices of behavior as cues of personality and

between targets and judges because otherwise the resulting intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86,

judgments might reflect the influence of those relationships 599-614. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.599

quite strongly (e.g., the average difference between the infor- Borkenau, P., & Ostendorf, F. (1998). The Big Five as states: How

mants’ global evaluations of the behavior of known vs. useful is the five-factor model to describe intraindividual varia-

unknown targets was d = .51 in the present study). tions over time? Journal of Research in Personality, 32, 202-

An important limitation of our study is that all informants 221. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1997.2206

were relatively fond of the targets. As a consequence, the Edwards, A. L. (1953). The relationship between the judged

desirability of a trait and the probability that the trait will be

influence of PEV-GE was probably underestimated due to

endorsed. Journal of Applied Psychology, 37, 69-106.

variance restriction (Leising et al., 2010; Peabody & Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2).

Goldberg, 1989). It seems likely that the force of this vari- Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

able would become stronger when including perceivers who Fleeson, W. (2001). Towards a structure- and process-integrated

differ more in how favorable or critical an image they have view of personality: Traits as density distributions of states.

of their respective targets. With regard to self-ratings, this Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 1011-1027.

may be achieved by including, for example, participants with doi:10.1037//0022-3514.80.6.1011

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

Leising et al. 163

Furr, R. M., & Funder, D. C. (1998). A multimodal analysis of per- Murray, S. L. (1999). The quest for conviction: Motivated cogni-

sonal negativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, tion in romantic relationships. Psychological Inquiry, 10, 23-

74, 1580-1591. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1580 34. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1001_3

Gallrein, A. M. B., Carlson, E. N., Holstein, M., & Leising, D. Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (1996). The ben-

(2013). You spy with your little eye—People are “blind” to efits of positive illusions: Idealization and the construction of

some of the ways in which they are consensually seen by satisfaction in close relationships. Journal of Personality and

others. Journal of Research in Personality, 47, 464-471. Social Psychology, 70, 79-98. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.79

doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.04.001 Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenom-

Kenny, D. A. (1994). Interpersonal perception: A social relations enon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2, 175-

analysis. New York, NY: Guilford. 220. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Kenny, D. A. (2004). PERSON: A general model of interpersonal Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can

perception. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 265- know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological

280. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_3 Review, 84, 231-259. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.3.231

Kim, H., Schimmack, U., & Oishi, S. (2012). Cultural differ- Paulhus, D. L. (2002). Socially desirable responding: The evolu-

ences in self- and other-evaluations and well-being: A study tion of a construct. In H. Braun, D. N. Jackson, & D. E. Wiley

of European and Asian Canadians. Journal of Personality and (Eds.), The role of constructs in psychological and educational

Social Psychology, 102, 856-873. doi:10.1037/a0026803 measurement (pp. 67-88). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Peabody, D., & Goldberg, L. R. (1989). Some determinants of fac-

Bulletin, 108, 480-498. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480 tor structures from personality-trait descriptors. Journal of

Leising, D. (2011). The consistency bias in judgments of one’s Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 552-567. doi:10.1037/

own interpersonal behavior. Two possible sources. Journal of 0022-3514.57.3.552

Individual Differences, 32, 137-143. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/ Sadler, P., & Woody, E. (2003). Is who you are who you’re talk-

a000046 ing to? Interpersonal style and complementarily in mixed-sex

Leising, D., & Bleidorn, W. (2011). Which are the basic meaning interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84,

dimensions of observable interpersonal behavior? Personality 80-96. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.80

and Individual Differences, 51, 986-990. doi.org/10.1016 Saucier, G. (1994). Separating description and evaluation in the

/j.paid.2011.08.003 structure of personality attributes. Journal of Personality

Leising, D., & Borkenau, P. (2011). Person perception, disposi- and Social Psychology, 66, 141-154. doi:10.1037/0022-

tional inferences and social judgment. In L. M. Horowitz & S. 3514.66.1.141

Strack (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal psychology: Theory, Snyder, M., & Campbell, B. (1980). Testing hypotheses about

research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions (pp. 157- other people: The role of the hypothesis. Personality and

170). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Social Psychology Bulletin, 6, 421-426. doi:10.1177/

Leising, D., Erbs, J., & Fritz, U. (2010). The letter of recommen- 014616728063015

dation effect in informant ratings of personality. Journal of Snyder, M., & Swann, W. B. (1978). Hypothesis-testing processes in

Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 668-682. doi:10.1037/ social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

a0018771 36, 1202-1212. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.36.11.1202

Leising, D., & Müller-Plath, G. (2009). Person–situation integra- Srivastava, S., Guglielmo, S., & Beer, J. S. (2010). Perceiving oth-

tion in research on personality problems. Journal of Research ers’ personalities: Examining the dimensionality, assumed sim-

in Personality, 43, 218-227. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.01.017 ilarity to the self, and stability of perceiver effects. Journal of

Leising, D., Ostrovski, O., & Zimmermann, J. (2013). Are we Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 520-534. doi:10.1037/

talking about the same person here? Inter-rater agreement in a0017057

judgments of personality varies dramatically with how much Swami, V., Stieger, S., Haubner, T., Voracek, M., & Furnham, A.

the perceivers like the targets. Social Psychological and (2009). Evaluating the physical attractiveness of oneself and

Personality Science, 4, 468-474. one’s romantic partner: Individual and relationship correlates

Lord, C. G., Lepper, M. R., & Preston, E. (1984). Considering of the love-is-blind bias. Journal of Individual Differences, 30,

the opposite: A corrective strategy for social judgment. 35-43. doi:10.1027/1614-0001.30.1.35

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1231-1243. Tice, D. M. (1991). Esteem protection or enhancement? Self-

doi:10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1231 handicapping motives and attributions differ by trait self-esteem.

McNulty, J. K., O’Mara, E. M., & Karney, B. R. (2008). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 711-725.

Benevolent cognitions as a strategy of relationship mainte- Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.60.5.711

nance: “Don’t sweat the small stuff.” But it is not all small West, T. V., & Kenny, D. A. (2011). The truth and bias model of

stuff. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 631- judgment. Psychological Review, 118, 357-378. doi:10.1037/

646. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.631 a0022936

Munro, G. D., Ditto, P. H., Lockhart, L. K., Fagerlin, A., Gready, Wood, D., Harms, P., & Vazire, S. (2010). Perceiver effects as pro-

M., & Peterson, E. (2002). Biased assimilation of sociopolitical jective tests: What your perceptions of others say about you.

argument: Evaluating the 1996 U.S. Presidential Debate. Basic Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 99, 174-190.

and Applied Psychology, 24, 15-26. doi:10.1037/a0019390

Downloaded from psp.sagepub.com at Universitaetsbibliothek on January 14, 2014

View publication stats

You might also like

- CarnesLickelJ-B PSPB 15Document13 pagesCarnesLickelJ-B PSPB 15Josh GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Rejected and Excluded Forevermore But EvDocument14 pagesRejected and Excluded Forevermore But Evspames23 spames23No ratings yet

- ActitudesDocument13 pagesActitudesguadalupecruzarias64No ratings yet

- Buffering Against Threat IdentityDocument14 pagesBuffering Against Threat IdentitySamiha MjahedNo ratings yet

- Extraversion, Social Interactions, and Well-Being During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Did Extraverts Really Suffer More Than Introverts?Document31 pagesExtraversion, Social Interactions, and Well-Being During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Did Extraverts Really Suffer More Than Introverts?vanessa.ruizzz.07No ratings yet

- Bulletin Personality and Social PsychologyDocument14 pagesBulletin Personality and Social PsychologyAb RazaNo ratings yet

- Habit in Personality and Social Psychology: Wendy WoodDocument15 pagesHabit in Personality and Social Psychology: Wendy Woodshubham kothareNo ratings yet

- Bulletin Personality and Social Psychology: Moving Narcissus: Can Narcissists Be Empathic?Document14 pagesBulletin Personality and Social Psychology: Moving Narcissus: Can Narcissists Be Empathic?Bunga Indira ArthaNo ratings yet

- Individual Perceptions of Self Actualization-What Functional Motives Are Linked To Fulfilling One's Full PotentialDocument16 pagesIndividual Perceptions of Self Actualization-What Functional Motives Are Linked To Fulfilling One's Full PotentialKatNo ratings yet

- Vendetti Etal 2014Document8 pagesVendetti Etal 2014Vishal KediaNo ratings yet

- Open Minded CognitionDocument18 pagesOpen Minded CognitionColin LewisNo ratings yet

- 2023 What Makes Groups EmotionalDocument14 pages2023 What Makes Groups EmotionalLucy VasquezNo ratings yet

- Ehrlich 2015Document13 pagesEhrlich 2015Muhammad HijrilNo ratings yet

- Pers Soc Psychol Rev 2015 Parks Leduc 3 29Document28 pagesPers Soc Psychol Rev 2015 Parks Leduc 3 29SaraNo ratings yet

- Fries Dorf 2015Document18 pagesFries Dorf 2015Anonymous Gim6abnNo ratings yet

- LikingGap CooneyDocument16 pagesLikingGap CooneyThanseem Abdul HameedNo ratings yet

- Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2013 Leitner 17 27Document12 pagesPers Soc Psychol Bull 2013 Leitner 17 27Rusu Daiana MariaNo ratings yet

- Baillargeon Et Al 2016 Psychological Reasoning in InfancyDocument30 pagesBaillargeon Et Al 2016 Psychological Reasoning in Infancymichel berdenNo ratings yet

- NewLookatSocialSupport PSPRDocument36 pagesNewLookatSocialSupport PSPRMabel PatiñoNo ratings yet

- Social Psychological and Personality Science 2012 Kredentser 341 7Document8 pagesSocial Psychological and Personality Science 2012 Kredentser 341 7OaniaNo ratings yet

- Busseri2011 - A Review of The Tripartite Structure of SWBDocument26 pagesBusseri2011 - A Review of The Tripartite Structure of SWBSamuel HasibuanNo ratings yet

- Self-Expression On Social Media: Do Tweets Present Accurate and Positive Portraits of Impulsivity, Self-Esteem, and Attachment Style?Document11 pagesSelf-Expression On Social Media: Do Tweets Present Accurate and Positive Portraits of Impulsivity, Self-Esteem, and Attachment Style?Jerry MastersNo ratings yet

- Benevolent Conformity: The Influence of Perceived Motives On Judgments of ConformityDocument13 pagesBenevolent Conformity: The Influence of Perceived Motives On Judgments of Conformitys.online2004No ratings yet

- Cognitive and Interpersonal Features of Intellectual HumilityDocument21 pagesCognitive and Interpersonal Features of Intellectual HumilityJoaquin De SilvaNo ratings yet

- Exlusao Social e Dor BernsteinClaypool2012aDocument13 pagesExlusao Social e Dor BernsteinClaypool2012apedroalouNo ratings yet

- Seeking Help in An Online Support Group - An AnalysisDocument4 pagesSeeking Help in An Online Support Group - An AnalysisArchana RebbapragadaNo ratings yet

- Problem-Solving Appraisal and Psychological Adjustment: January 2012Document87 pagesProblem-Solving Appraisal and Psychological Adjustment: January 2012Wilson Rafael Cosi ChoqqueNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Social Anxiety DisorderDocument30 pagesJurnal Social Anxiety Disordernaila syawalita tsaniNo ratings yet

- Selfie and Self - The Effect of Selfies On Self-Esteem and Social SensitivityDocument7 pagesSelfie and Self - The Effect of Selfies On Self-Esteem and Social SensitivityIonela CazacuNo ratings yet

- Human Abilities: Emotional Intelligence: Annual Review of Psychology February 2008Document36 pagesHuman Abilities: Emotional Intelligence: Annual Review of Psychology February 2008Alexandra StanciuNo ratings yet

- Complaining Behavior in Social Interaction: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin June 1992Document12 pagesComplaining Behavior in Social Interaction: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin June 1992Alyssa GoNo ratings yet

- Narrative Identity: Current Directions in Psychological Science June 2013Document8 pagesNarrative Identity: Current Directions in Psychological Science June 2013Chemita UocNo ratings yet

- Ecab 2Document30 pagesEcab 2Hugo SchmidtNo ratings yet

- Shoda Et Al - 2002Document11 pagesShoda Et Al - 2002dallaNo ratings yet

- S Komissarouk, A Nadler (2014)Document14 pagesS Komissarouk, A Nadler (2014)Jennifer KNo ratings yet

- McAdams Olson 2010 Personality DevelopmentDocument26 pagesMcAdams Olson 2010 Personality Developmentatieyhayati_No ratings yet

- Internet Research in Psychology 2015Document30 pagesInternet Research in Psychology 2015Alejandro GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Blakemore Mills 2014 Is Adolescence A Sensitive Period For Sociocultural ProcessingDocument24 pagesBlakemore Mills 2014 Is Adolescence A Sensitive Period For Sociocultural ProcessingLoes JankenNo ratings yet

- Bruck AyalewDocument73 pagesBruck AyalewBruk AyalewNo ratings yet

- Social Constructionist Contributions ToDocument8 pagesSocial Constructionist Contributions ToJamesNo ratings yet

- Highlighting Relatedness Promotes ProsocDocument14 pagesHighlighting Relatedness Promotes ProsocJustin CatubigNo ratings yet

- Forstmann 2016 Sequential Sampling Models in CogniDocument28 pagesForstmann 2016 Sequential Sampling Models in CogniDeissy Milena Garcia GarciaNo ratings yet

- ClinicalPsychologicalScience 2013 Goldin 2167702613476867Document11 pagesClinicalPsychologicalScience 2013 Goldin 2167702613476867Elena MathewNo ratings yet

- Science Perspectives On Psychological: Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition: Advancing The DebateDocument20 pagesScience Perspectives On Psychological: Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition: Advancing The DebateMoopsNo ratings yet

- Adolphs 2009 TheSocialBrainDocument28 pagesAdolphs 2009 TheSocialBrainKatherine SalazarNo ratings yet

- Forme Si Functii Ale Emotiilor SocialeDocument8 pagesForme Si Functii Ale Emotiilor SocialeDaniela GăujăneanuNo ratings yet