Professional Documents

Culture Documents

B3W Might Not Be Able To Compete With BRI in Southeast Asia, But That's Okay - The Diplomat

Uploaded by

Sajid Usman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views6 pagesOriginal Title

B3W Might Not Be Able to Compete With BRI in Southeast Asia, But That’s Okay – The Diplomat

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views6 pagesB3W Might Not Be Able To Compete With BRI in Southeast Asia, But That's Okay - The Diplomat

Uploaded by

Sajid UsmanCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

TRANS-PACIFIC VIEW | DIPLOMACY | SOUTHEAS

B3W Might Not Be

Able to Compete

With BRI in

Southeast Asia,

But That’s Okay

Rather than competing in a

sector where China is

strong – infrastructure –

B3W should focus on U.S.

strength areas.

By Maria Adele Carrai and William Yuen Yee

February 10, 2022

Credit: Depositphotos

The opening of a $5.9 billion high-speed railway

that links Laos to China has reignited questions

about the ability of the nascent U.S.-led Build

Back Better World initiative (B3W) to compete

with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in

Southeast Asia. Instead, the Biden

administration should focus on the United

States’ other competitive advantages over China

– technology, healthcare, and education – to

effectively counter Beijing’s rising influence in

the region.

The Biden administration has embraced

Southeast Asia as a cornerstone of its policy in

the Indo-Pacific. U.S. President Joe Biden himself

attended the virtual East Asia Summit in

October 2021, an annual gathering that his

predecessor repeatedly snubbed. In his

December 2021 visit to the region, Secretary of

State Antony Blinken proclaimed that “much of

the planet’s future will be written in the Indo-

Pacific.”

Blinken spent much of his visit promoting B3W,

with its emphasis on “freedom” and “openness,”

as an alternative to China’s BRI. However, such

comments misunderstand the challenge posed

by China’s BRI and the interests of Southeast

Asian nations. China’s primary advantage in

infrastructure diplomacy lies in its one-stop-

shop package of project finance, insurance, and

construction for developing nations.

Furthermore, recent polls indicate that many

ASEAN residents support China’s activities, a

sign that they might be less enticed by

aspirational soliloquies about democracy and

more concerned with building usable roads,

bridges, and airports.

By comparison, the B3W is less attractive. Many

low- and middle-income countries prefer

Beijing’s state-backed loans over higher-cost and

shorter-term private funding from Western

financiers. The U.S. and other G-7 countries

often impose what feels like onerous conditions

that delay project implementation and increase

costs. On top of that, B3W relies on unreliable

private funding. It is difficult to convince

private firms in developed G-7 countries to

invest in the developing world, which they view

as high risk and low reward.

Since the 1990s, the United States – like many

other Western economies – has drastically

reduced its infrastructure investment in

developing nations. And despite efforts under

the Trump administration to reinvigorate such

financing, the numbers still pale in comparison

to investments from China. In 2019, the U.S.

International Development Finance Corporation

capped its spending at $60 billion. China has

already spent an estimated $200 billion on the

BRI, and some project its overall investments

will reach $1.3 trillion by 2027.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe

for full access. Just $5 a month.

Moreover, unlike China, the United States does

not boast much infrastructure experience at

home. Since the 1950s, the U.S. has spent less

than 1 percent of GDP on its own domestic

infrastructure development. The BRI-backed

railway in Laos highlights this disparity. As

former Singaporean diplomat Kishore

Mahbubani said, Laos – one of Southeast Asia’s

poorest countries – “now has a faster train than

anything the United States has.”

When it comes to infrastructure, then, the U.S.

significantly trails China in funding,

institutional mechanisms, and experience.

While the Biden administration can and should

continue to push B3W, especially given the high

standards that it promotes, it is also time to

grapple with a hard truth: Build Back Better

World might not be able to effectively compete

with the Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast

Asia.

Instead, the Biden administration should turn to

other areas of economic and diplomatic

engagement. A U.S.-ASEAN digital trade

agreement to set regional rules on cross-border

data flows, privacy protection, and artificial

intelligence is a start. In 2020, China’s trade with

Southeast Asia totaled $685 billion, nearly

double that of the United States. Such an

agreement will be critical given the United

States’ continued absence from Asia’s two

biggest trade pacts: the Regional Comprehensive

Economic Partnership and the Comprehensive

and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific

Partnership. China is a member of the former

and recently applied to join the latter.

The United States could also leverage its

comparative advantages in healthcare and

education to strengthen ties with Southeast

Asia. While China enthusiastically provided its

domestically produced COVID-19 vaccines to

ASEAN countries, leading officials across the

region raised concerns about the efficacy of

such shots, with many ultimately embracing

Western-made boosters. The Biden

administration should continue to send vaccines

to the ASEAN nations that need it: Countries like

Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam have vaccinated

less than 25 percent of their citizens. The U.S.

should also increase collaboration with local

governments to combat diseases like HIV and

malaria. The Biden administration took a step in

the right direction by allocating $40 million to

such efforts last October. Finally, to strengthen

cultural ties, the United States should offer more

scholarships to Southeast Asian students, a

strategy successfully used by the Japanese

government. 80,000 students from ASEAN

countries study in China, while 60,000 study in

the United States.

To compete with China in Southeast Asia, the

Biden administration should substantiate B3W’s

democratic aspirations. Increasing economic

engagement, health cooperation, and student

exchanges with ASEAN countries is a good start.

You have read 3 of your 5 free articles this

month.

Subscribe to

Diplomat All-Access

Enjoy full access to the website and get an

automatic subscription to our magazine with a

Diplomat All-Access subscription.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

Already a subscriber? Login here

AUTHORS

GUEST AUTHOR

Maria Adele Carrai

Maria Adele Carrai is an assistant professor of

Global China Studies at New York University

Shanghai and an associate at the Harvard

University Asia Center. Her research explores the

history of international law in East Asia and

investigates how China’s rise as a global power is

shaping norms and redefining the international

distribution of power.

GUEST AUTHOR

William Yuen Yee

William Yuen Yee is a research assistant for

Professor Thomas Christensen at the Columbia-

Harvard China and the World Program. He has

previously written about China's foreign relations

and international trade for the Center for

Strategic and International Studies and the

Jamestown Foundation.

TAGS

Trans-Pacific View Diplomacy Southeast Asia China

United States B3W Belt and Road in Southeast Asia

Build Back a Better World Chinese infrastructure in ASEAN

Chinese infrastructure investment

You might also like

- Complete Saas PresentationDocument36 pagesComplete Saas PresentationDavid BandaNo ratings yet

- Chinese Soft PowerDocument137 pagesChinese Soft PowerVirtan Diana AdelinaNo ratings yet

- Thayer Will Vietnam and The U.S. Become Strategic Partners This Year RevisedDocument3 pagesThayer Will Vietnam and The U.S. Become Strategic Partners This Year RevisedCarlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Thayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 6Document3 pagesThayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 6Carlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Thayer U.S.-China Rivalry and Impact On VietnamDocument2 pagesThayer U.S.-China Rivalry and Impact On VietnamCarlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Concepts Competitiveness and Globalization Hitt 11th Edition Solutions ManualDocument29 pagesStrategic Management Concepts Competitiveness and Globalization Hitt 11th Edition Solutions ManualJohnny Adams100% (28)

- Thayer US-Vietnam Relations Post Mortem - 5Document4 pagesThayer US-Vietnam Relations Post Mortem - 5Carlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Thayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 7Document2 pagesThayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 7Carlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Chapter # 12 Exercise - Problems - AnswersDocument5 pagesChapter # 12 Exercise - Problems - AnswersZia UddinNo ratings yet

- Blackwill USCHINARELATIONSDETERIORATE 2021Document7 pagesBlackwill USCHINARELATIONSDETERIORATE 2021lextpnNo ratings yet

- America Shouldn't Copy China's Belt and Road Initiative - Foreign AffairsDocument7 pagesAmerica Shouldn't Copy China's Belt and Road Initiative - Foreign AffairsCintia DiasNo ratings yet

- DA - Diplomatic Capital - DDI 2022Document158 pagesDA - Diplomatic Capital - DDI 2022anikakulkarni22No ratings yet

- 李昭逸 Lee Zhao Yi Charles 2002055404Document1 page李昭逸 Lee Zhao Yi Charles 2002055404Charles LeeNo ratings yet

- Thayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 4Document3 pagesThayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 4Carlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- Geopolitical Strategic Importance of PakistanDocument4 pagesGeopolitical Strategic Importance of PakistanSyed Maaz HassanNo ratings yet

- China BD Rukhsana KibriaDocument5 pagesChina BD Rukhsana KibriaS. M. Hasan ZidnyNo ratings yet

- Countries Against BriDocument8 pagesCountries Against Britakudzwa kunakaNo ratings yet

- The Road To CompetitionDocument3 pagesThe Road To CompetitionSaqibullahNo ratings yet

- Biden Says US Prepared To Beat China For 21st Century Competition Not Looking For Conflict With BeijingDocument4 pagesBiden Says US Prepared To Beat China For 21st Century Competition Not Looking For Conflict With BeijingVAISHALI BASU SHARMANo ratings yet

- Competing With China in Southeast Asia: The Economic ImperativeDocument8 pagesCompeting With China in Southeast Asia: The Economic Imperativeviethai phamNo ratings yet

- Thayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 5Document3 pagesThayer President Biden To Visit Vietnam - Scene Setter - 5Carlyle Alan ThayerNo ratings yet

- BRICS, Quad, and India's Multi-Alignment Strategy - South Asian VoicesDocument4 pagesBRICS, Quad, and India's Multi-Alignment Strategy - South Asian Voicesahmad khanNo ratings yet

- BRICS Without Mortar?Document5 pagesBRICS Without Mortar?irfan_oct26No ratings yet

- Strategic Asia 2020 OverviewDocument44 pagesStrategic Asia 2020 OverviewAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Final Research PaperDocument20 pagesFinal Research Paperapi-581490471No ratings yet

- Moments of Clarity: Uncovering Important Lessons For 2023Document20 pagesMoments of Clarity: Uncovering Important Lessons For 2023The Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- The Inconvenient Truth: Aspirations Vs Realities of Coexistence Between "The West" and ChinaDocument5 pagesThe Inconvenient Truth: Aspirations Vs Realities of Coexistence Between "The West" and Chinarahul kadamNo ratings yet

- China's Latin America and Caribbean RelationDocument3 pagesChina's Latin America and Caribbean RelationramNo ratings yet

- fOREIGN AFFAIRSDocument58 pagesfOREIGN AFFAIRSMuhammad SaeedNo ratings yet

- A New Era of GreatDocument3 pagesA New Era of Greatsemp mardanNo ratings yet

- China Disadvantage - Harvard 2013Document34 pagesChina Disadvantage - Harvard 2013Brad MelocheNo ratings yet

- XuetongDocument6 pagesXuetongVasil V. HristovNo ratings yet

- US Should Focus On Economic Diplomacy in The Middle East - Arab NewsDocument4 pagesUS Should Focus On Economic Diplomacy in The Middle East - Arab Newskhurram saeedNo ratings yet

- 2 Mobley BeltRoadInitiative 2019Document22 pages2 Mobley BeltRoadInitiative 2019luanadiasfrancoNo ratings yet

- Addressing China's Rising Influence in AfricaDocument23 pagesAddressing China's Rising Influence in AfricaUn-Fair WebNo ratings yet

- Obama Visit To IndiaDocument3 pagesObama Visit To IndiaRohan ShahNo ratings yet

- EDITORIAL ANALYSIS Chinas Wolf Warrior Era 2Document5 pagesEDITORIAL ANALYSIS Chinas Wolf Warrior Era 2shiva pandeyNo ratings yet

- China Disadvantage - HSS 2013Document296 pagesChina Disadvantage - HSS 2013Elias GarciaNo ratings yet

- Dollar 2018Document16 pagesDollar 2018lalisangNo ratings yet

- The United States, China, and The Indo-Pacific StrategyDocument17 pagesThe United States, China, and The Indo-Pacific StrategyLia LiloenNo ratings yet

- Money Borrowing Trap: China's International StrategyDocument10 pagesMoney Borrowing Trap: China's International StrategyRitzzNo ratings yet

- Joe BiedenDocument10 pagesJoe BiedenFarah KhanNo ratings yet

- Short of War How To Keep US Chinese Confrontation - FA Mar-APR 2021Document16 pagesShort of War How To Keep US Chinese Confrontation - FA Mar-APR 2021veroNo ratings yet

- The Sabotage: How the USA Planned to Undermine China's Belt and Road ProjectFrom EverandThe Sabotage: How the USA Planned to Undermine China's Belt and Road ProjectNo ratings yet

- IB Mahrukh Oct 29 2020Document5 pagesIB Mahrukh Oct 29 2020Muhammad IshaqNo ratings yet

- 6IB006 Assessment 1 Coursework 2040721Document12 pages6IB006 Assessment 1 Coursework 2040721Kisan BhagatNo ratings yet

- Moldasbayeva Dilyara Response P1Document4 pagesMoldasbayeva Dilyara Response P1ДИЛЯРА МОЛДАСБАЕВАNo ratings yet

- Usman Zulfiqar Ali Research PaperDocument15 pagesUsman Zulfiqar Ali Research PaperUsman AleeNo ratings yet

- Indo PacificStrategyvs - beltandRoadInitiativeDailysunDocument4 pagesIndo PacificStrategyvs - beltandRoadInitiativeDailysunPooja LamaNo ratings yet

- The Age of Slow Growth in China Foreign AffairsDocument11 pagesThe Age of Slow Growth in China Foreign Affairshenrique.silva.eiraNo ratings yet

- Why The US Should Join AIIBDocument2 pagesWhy The US Should Join AIIBLincoln TeamNo ratings yet

- De La Cruz - Debt Trap Diplomacy - China's Economic Strategy Through Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications To The Philippine EconomyDocument25 pagesDe La Cruz - Debt Trap Diplomacy - China's Economic Strategy Through Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications To The Philippine EconomyRyan Andrei De La CruzNo ratings yet

- Mobley BeltRoadInitiative 2019Document22 pagesMobley BeltRoadInitiative 2019Scipione AfricanusNo ratings yet

- Caixin Global - Political Economy 05.19.2023Document3 pagesCaixin Global - Political Economy 05.19.2023austinsu.hk2016No ratings yet

- If 10029Document3 pagesIf 10029kashiram30475No ratings yet

- Opinion - The Expansion of BRICS Challenges and UncertaintiesDocument3 pagesOpinion - The Expansion of BRICS Challenges and UncertaintiesRahmatullah MaitloNo ratings yet

- The Hindu 1, 01-May-2009, Page: 010: Hundred Days, Miles To GoDocument8 pagesThe Hindu 1, 01-May-2009, Page: 010: Hundred Days, Miles To GoManish JodhwaniNo ratings yet

- Pol 101 Final DraftDocument24 pagesPol 101 Final DraftKim Hirai ChanNo ratings yet

- Question 6 US China After 1991Document8 pagesQuestion 6 US China After 1991Kazi Naseef AminNo ratings yet

- What To Expect From US-India Relations in 2016 - The DiplomatDocument3 pagesWhat To Expect From US-India Relations in 2016 - The DiplomatAnurag AryaNo ratings yet

- China and The West Competing Over Infrastructure in Southeast AsiaDocument12 pagesChina and The West Competing Over Infrastructure in Southeast AsiaJane CollenNo ratings yet

- Is Multi Alignment A Path To Chaos or Order PDFDocument10 pagesIs Multi Alignment A Path To Chaos or Order PDFKashi RanaNo ratings yet

- 10 June 2022Document9 pages10 June 2022Ali HussainNo ratings yet

- Daily Current Affairs - 1-2 May 2023Document3 pagesDaily Current Affairs - 1-2 May 2023Sajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- Pak Studies FinalDocument9 pagesPak Studies FinalSajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- Daily Current Affairs - 26 April 2023Document2 pagesDaily Current Affairs - 26 April 2023Sajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- Essay OutlineDocument3 pagesEssay OutlineSajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- 9-64-BSc (Hons) Agriculture-1st-1Document4 pages9-64-BSc (Hons) Agriculture-1st-1Sajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- Israel War Current AffairsDocument8 pagesIsrael War Current AffairsSajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- 6-Scientific Instruments Names PDF Notes For All Competitive ExamsDocument9 pages6-Scientific Instruments Names PDF Notes For All Competitive ExamsSajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- BRI - How China's Belt and Road Took Over The World - The DiplomatDocument14 pagesBRI - How China's Belt and Road Took Over The World - The DiplomatSajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- Political PhilosophyDocument14 pagesPolitical PhilosophySajid UsmanNo ratings yet

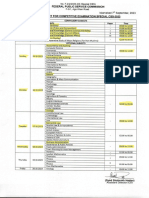

- Date Sheet Competitive Examination Special CSS-2023Document1 pageDate Sheet Competitive Examination Special CSS-2023Sajid UsmanNo ratings yet

- Cbe Joining Instruction For Diploma 1 September Intake 2023-2024 Jif2Document10 pagesCbe Joining Instruction For Diploma 1 September Intake 2023-2024 Jif2Daniel EudesNo ratings yet

- Formulaire Accepteur Agrege Marchand English VERSIONDocument2 pagesFormulaire Accepteur Agrege Marchand English VERSIONGerald NONDIANo ratings yet

- Pass4sure: Everything You Need To Prepare, Learn & Pass Your Certification Exam EasilyDocument8 pagesPass4sure: Everything You Need To Prepare, Learn & Pass Your Certification Exam Easilysherif adfNo ratings yet

- Sample Business CaseDocument19 pagesSample Business CasepreetigopalNo ratings yet

- Tittle ProposalDocument16 pagesTittle ProposalJoanne Vera CruzNo ratings yet

- April 202 FdA Business Environment Assignment 2 L4 AmendedDocument5 pagesApril 202 FdA Business Environment Assignment 2 L4 AmendedHussein MubasshirNo ratings yet

- Wayne Johnson AnnouncementDocument5 pagesWayne Johnson AnnouncementAlexandria DorseyNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledReplacement AccountNo ratings yet

- Steps Approach Coopsoc Audit 30062018Document150 pagesSteps Approach Coopsoc Audit 30062018Ritesh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- LG Microwave BillDocument1 pageLG Microwave BillAman GuptaNo ratings yet

- RBC Spherical Plain Bearings: Interchange TablesDocument2 pagesRBC Spherical Plain Bearings: Interchange Tablesjake leiNo ratings yet

- Turner (2020)Document37 pagesTurner (2020)Dhara Kusuma WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Solutions Manual: Accounting: Building Business SkillsDocument31 pagesSolutions Manual: Accounting: Building Business SkillsNicole HungNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Economics 9Th Edition John Sloman Full ChapterDocument67 pagesEssentials of Economics 9Th Edition John Sloman Full Chapterpeter.voit454100% (5)

- 1e1 S4hana2022 BPD en UsDocument60 pages1e1 S4hana2022 BPD en UsprajeethNo ratings yet

- VP Institutional Asset Management in Washington DC Resume Lisa DrazinDocument3 pagesVP Institutional Asset Management in Washington DC Resume Lisa DrazinLisaDrazinNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Framework ReviewerDocument4 pagesConceptual Framework ReviewerMA. MIGUELA MACABALESNo ratings yet

- Brief History of Saint Michael CollegeDocument4 pagesBrief History of Saint Michael CollegeAdoremus DueroNo ratings yet

- Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar MissionDocument55 pagesJawaharlal Nehru National Solar MissionIshan TiwariNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Nursing: A Concept Analysis: January 2016Document5 pagesInnovation in Nursing: A Concept Analysis: January 2016shejila c hNo ratings yet

- Management of Finacial MarketDocument3 pagesManagement of Finacial MarketDHAIRYA MARADIYANo ratings yet

- BSBHRM501 Student Workbookpdf 2001Document126 pagesBSBHRM501 Student Workbookpdf 2001Suraj Kumar S75% (4)

- Meghmani Organics Limited Annual Report 2019 PDFDocument254 pagesMeghmani Organics Limited Annual Report 2019 PDFmredul sardaNo ratings yet

- Annual Report Icici BankDocument132 pagesAnnual Report Icici BankMohit MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- A Medium For Male Escort Jobs in MumbaiDocument5 pagesA Medium For Male Escort Jobs in MumbaiBombay HotboysNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Unpaid SellerDocument6 pagesMeaning of Unpaid Sellerr.k.sir7856No ratings yet

- Philly POPS Files Lawsuit Against Philadelphia Orchestra and Kimmel Center Inc.Document7 pagesPhilly POPS Files Lawsuit Against Philadelphia Orchestra and Kimmel Center Inc.Kristina KoppeserNo ratings yet