Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dilthey and Gadamer

Uploaded by

anshulpatel0608Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dilthey and Gadamer

Uploaded by

anshulpatel0608Copyright:

Available Formats

Dilthey and Gadamer: Two Theories of Historical Understanding

Author(s): David E. Linge

Source: Journal of the American Academy of Religion , Dec., 1973, Vol. 41, No. 4 (Dec.,

1973), pp. 536-553

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1461732

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Journal of the American Academy of Religion

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CRITICAL DISCUSSION

Dilthey and Gadamer

Two Theories of Historical Understanding

DAVID E. LINGE

ST "O the impenetrable depths within myself," wrote Wilhelm D

1910, "I am an historical being.... The first condition for the

bility of historical science lies in the fact that I am myself an h

being - that the one who studies history is the same one who makes

sentences of Dilthey's give expression to the central problem of t

namely, the problem of the relation between historical understanding

historicity of human existence. Most philosophers have taken the rela

tween these two notions to be one of mutual exclusion. The unqualified

tion of man's historicity seems to lead directly to a relativism that m

kind of objective knowledge impossible. Hence it is not surprising

author of the above words is generally considered one of the fathers of

ism. Writing at the turn of the century, Dilthey was indeed one of t

thinkers to see that the result of historical scholarship - its insight int

a creature of history - threatened to undercut the very ideal of objecti

which historical scholarship itself is based.

In this paper, I shall examine the attempts of two thinkers - Wilh

they and Hans-Georg Gadamer - to work out a positive relationship b

the historicity of the knower and the objectivity of historical interpret

sharply conflicting theories of these thinkers represent two of the prin

in which German philosophy in the twentieth century has sought to

terms with the radical historicity of man while avoiding the pitfalls of

1 Wilhelm Dilthey, Gesammelte Schriften (14 vols.; Stuttgart: Teubner,

Vol. VII, p. 278. (Hereafter cited as GS, with appropriate volume number fo

DAVID E. LINGE (Ph.D., Vanderbilt University) is Assistant Professor of

Studies at The University of Tennesee in Knoxville.

536

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 537

The background of the problem

viction that has become increasi

years - the conviction usually re

sciousness" The rise of what I w

the development of scientific h

subsequent accumulation of a va

whole range of social, political, a

of its development of the natur

teenth century to our own time

torical awareness it has bequea

humanities has been left untouch

during the past century, not on

precedented mass of informatio

adopt a historical point of view

important part of its task to exa

it is concerned from the point of

and the various historical influen

The term "historical consciou

signifies more than the emergen

the methodology of present-day

standing of reality, to a convict

categories constitute the widest

"History," said Ernest Troeltsch,

of things or a partial satisfaction

of all thinking about values and

species regarding its nature, orig

has thus come to constitute a wo

to a wider framework - to absolutes or to realities not accessible to historical

thinking and historical investigation - is no longer possible.

This view of things stands in stark contrast to the sense of the meaningful-

ness of history which men had before the present century. Until the close of

the last century, men considered history intelligible and knowledge of it impor-

tant only because history itself was deemed to fit into a larger metaphysical con-

text. For medieval man, history was intelligible in terms of the supernatural

end which God had ordained for it and not in terms of itself. During the eigh-

teenth and nineteenth centuries, this supernatural framework for history and

historical understanding was more and more called into question; the meaning

of history became man himself, his struggle towards and gradual realization of

his natural capacities and ideals. Hence the foundations of historical under-

*Ernst Troeltsch, Die Absolutheit des Christentums und die Religionsgeschichte (Tii-

bingen: Mohr, 1929), p. 3.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

538 DAVID E. LINGE

standing at the time of

tury reflected the gen

control and direct him

goals, the validity of

medieval and the mod

and historical knowled

was thought to be cont

providence, for the ot

Even before the collap

War, historical conscio

qualifying in principle

The German theologia

torical thinking: "The

asserts, "consists in the

torical'. What earlier a

historically, but for t

historical becomes the

relativism, the growin

longer regards history

nificance. At most, hi

tinual positing of abso

understood historically

prevents one from tak

knowledge that fill the

History does indeed kno

norm or good. These oc

of perfection, in a teleo

scendentally founded no

the processes of positin

versal validity. By trac

values, goods or norms,

the unconditional posit

the age is limited.'

Historical consciousne

ofevery man and every

But what holds for o

is a small step from D

erosion of the tradition

mode of being of the t

less immersed in histo

SGerhard Ebeling, Wor

' GS, VII, p. 173.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 539

silenced by the relativity of their

his own claims will fare any bett

subordinates - or better, swallow

given in the past, but now, in F

bites its own tail, this mode of in

himself.5 The final and most de

therefore, is not its ever more r

rather its radical historicization

historical knower himself.

And this, of course, is the poin

brate a logical victory over their

in the triumph of Socratic philos

goras. The critics of historicism

the knower of history as well as

dations for objective knowledge

the historicist's presuppositions r

the ideal of objective knowledge

opponents of historicism insist, t

maintain both their assertion of

and their claim to a scientific his

objectively valid knowledge of h

able enough that most would-be

affirmation of human historicity,

that has allowed them to salvage

by exempting the knower himse

historicity. The most prominent

seen in the great interest philos

have shown in methodological qu

any rate, even the brief analysis

taken leads one to suspect that th

nated historical studies at the tu

vague sense of self-contradiction

The subtle continuation by the

set out to overcome is nowhere m

interpretation he adopts. For it i

ogy - that is, by virtue of his me

control- that the knower comes

remain unaffected by his histor

understanding with which the hi

at which we gain an insight into

to history. In the following sect

5 Friedrich Meinecke, Zur Theorie

Koehler, 1959), p. 215.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

540 DAVID E. LINGE

of historical understan

main interest is not in

of historical interpreta

to the reflexive questi

thinkers make regardin

historicity of the know

II

Dilthey's philosophy of life stands within the great tradition of German his-

torical scholarship which has its roots in early nineteenth-century romanticism

and includes the work of such thinkers as Schleiermacher, Ranke, Droysen, and

the Historical School. But it is especially Dilthey, in a series of writings that

appeared between 1900 and his death in 1911, who worked out the historicist

implications of this heritage.

Throughout his writings, Dilthey posits a unique connection between life

and history. "In its subject matter," he asserts, "life is identical with history.

And history consists in life of all kinds in the most varying circumstances. His-

tory is only life viewed in terms of the continuity of mankind as a whole."6

Life is the ultimate, underlying ground of all human thought and action and the

source from which the entire socio-historical world arises. It is the compre-

hensive context in which individual, personal lives take place. But we can ap-

proach life only through the study of the myriad forms in which it manifests

itself in the course of history. "History must teach us what life is; yet, because

it is the course of life in time, history is dependent on life and derives its con-

tent from it."'

If we are to understand what Dilthey means by historicity, we must first

of all consider his concept of the organic system of consciousness that is at the

basis of human life and all its historical manifestations. The human studies

(Geisteswissenschaften) are distinct from the natural sciences precisely becaus

their mode of understanding presupposes an inner and underived mental struc-

ture which is present to the individual in experience and reflection on experienc

The continuity of life that embraces both the subject and the objects of historica

knowledge is seen in the fact that this mental structure is at the basis of the

knower's own life as well as at the basis of the phenomena he studies.

For Dilthey, the initial contact of the self with its environment is not a pas

sive recording of impersonal, neutral objects and processes. Rather, immediate

awareness of our involvement in the world occurs on the level of vital interac-

tion. Drives and instincts innate in the self run up against the resistance of what

is beyond it.8 Consequently, the basic form of our mental structure is determined

6 GS, VII, p. 256.

7 GS, VII, p. 262.

8 Cf., GS, V, pp. 98-105.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 541

in lived experience by the recipr

environment and responds purpo

therefore an original element of

the world is originally present in

relation in which it stands. Dilth

up out of such preconceptual inv

... There is nothing that does not

thing is related to it, the state of the

and people around it. There is not

to me; for me it involves pressure o

a restriction of my will, importanc

or resistance, distance or strangene

tory or permanent, these people a

existence or heighten my powers; or

pressure on me and drain my streng

only in the life-relation to me prod

the basis of life itself, types of beh

evaluation and the setting of purpos

other. In the course of life they for

determine all activity.'

Reflection presupposes lived ex

what is given in it. The self thus

albeit in a pre-reflective and not

which develops on this pre-conce

As reflection clarifies and draws

ness, these elements already belo

perience. The structural unity of

somehow subsequent to lived exp

only insofar as it belongs ab initi

present in it. This is not of cour

structure is consciously present i

the organic whole of mental life

manent in the particular lived exp

in that particular but rather, star

tion which uncovers and draws o

making up the total system. Thu

and future pervade each momen

spontaneously determine that mo

In this way reflection arises s

draws out and clarifies the mean

initial encounter with the world.

of the comprehensive system of t

9 GS, VII, pp. 131-32.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

542 DAVID E. LINGE

matic awareness. Neve

the mental structure,

than the mere chron

most primordial level

place according to thei

self-reflection can ran

can be transformed f

ciplined and sustained

out and accentuates m

forgetfulness. He rem

his life goals, and the

of those goals. Old let

projects into his futu

into reflection, and t

of lived experience and

with historical interp

understanding.

There are two feature

prove to be the essent

as such.

(1) Historical underst

part-whole structure.

significance for the c

to which they belong.

interpretation as the p

interrelatedness. And a

in their significance a

interpreter's view thr

familiar with the her

vidual structure that fo

of a text or a personal

historical epoch. In all

for in en them we also

parts have their signi

own study of the Prus

in Italy are, therefore

the personal self, the

of themselves because

mark them off from what went before and what follows. "It is the task of his-

torical analysis," Dilthey asserts, "to discover the climate which governs the con-

crete purposes, values and ways of thought of a period. Even the contrasts which

prevail there are determined by this common background. Thus, every action,

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 543

every thought, every common activ

has its significance through its re

For Dilthey, hi then, the ideal of

of itself. The interpreter does no

external perspective - for instance

of eternal values - nor does he cr

of view as false or delusory. Inde

immersing oneself in the object,

a manifestation of something bey

toward the individual that rescues

ditional worldviews, each of whic

reality. "Every expression of life

expresses something that is part o

itself. There is nothing in it that

(2) Secondly, historical understa

from sensuously given manifesta

directly given, namely, the indivi

tions of life presuppose. That is t

the existence of a historico-cultu

following Hegel, calls objective sp

"the past is a permanently enduri

style of life and the forms of soci

society has created for itself, to

philosophy.... From this world of

from earliest childhood. It is the

people and their expressions take

objectified itself contains somethi

All expressions, intentional or un

the individual life structure, belo

stitute the point of departure for

expressive behavior such as gestu

tions which tell us something of t

tific expressions gain their preci

without any reference to an indiv

stances. Yet even Newton's Princi

'" GS, VII, pp. 154-55; cf. also, p. 1

limited but specific sense that they al

sufficient to justify Dilthey's procedu

larger realities, unlike personal selves

are only logical subjects. Cf. GS, VII

n GS, VII, p. 234; cf. also, p. 138.

1~ GS, VII, p. 208.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

544 DAVID E. LINGE

torical understanding

author or the mind of

primarily dependent o

the conversation, the

All of these presuppos

Indeed, such expression

than their author cons

cation of such clues to

hope to understand th

they argues, therefore,

these life-manifestatio

the individual life-who

These two essential ch

standing to be one of

knower into the horizo

for the possibility of u

known are individual s

system of life appears

organ by which I unde

effect become the oth

life-structure, not in t

by reflectively graspin

son or age.

Now is my it

content

cism are present in Di

model- dominant, at le

phy and historiography

tory. Dilthey

assumes

the very success of hi

knower's negating and

his object. The aim of

prejudices, and thus to

in terms of the life-w

his own present as a

achieved in direct prop

zons that, on Dilthey's

toricity. Paradoxically

poses no real limitatio

history a living reality

it did those of the pas

behind by the utilizati

This alienation from h

standing, has profoun

understanding liberate

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 545

dom from the prejudices given in

cal horizons. From his methodol

comes to see the relativity and th

The historical consciousness of th

of every human social condition an

the last step towards the liberation

to enjoy every experience to the fu

as if there were no system of philo

from knowledge through concepts

webs of dogmatic thought. Everythi

relived and interpreted, opens pers

And equally, we accept the evil, hor

as containing some reality which mu

thing that cannot be conjured aw

tinuity of creative forces asserts itse

What Dilthey is offering us he

quite at odds with the one he im

manner reminiscent of Hegel, D

constitutes a kind of heightened

itself and gaining a final sovereig

standing gives life what the olde

cal consciousness could not: a con

onesidedness which, as Dilthey se

Thus the cogency of Dilthey's

knower's own transcendence of

the historicist is magically eman

universal. This conflict, implicit

tific historical knowledge and th

solved by Dilthey. At the very e

epistemological consequences tha

of historicism consistent by p

historical Weltanschauung," he sa

the final chains which natural sc

where are the means for overcom

break in? I have labored my ent

If I fall along the way, I hope my

it to the end."14 But how Dilth

hard to discern, nor did his stud

Dilthey did, however, succeed in

his conception of historical know

work leaves us with a choice betw

because of the threat it poses to

* GS, VII, pp. 290-91.

' GS, V, p. 9.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

546 DAVID E. LINGE

that model of historic

value in his historicism

unanimous in adopting

a concerted effort to e

III

It is man's situation to be present in and to understand his world in terms

of patterns of meaning that are antecedent to reflection and color reflection when

it occurs. Dilthey intended his concept of historicity to illuminate this perspec-

tival character of human consciousness. But if we now recall his proposition

that "the one who studies history is the same one who makes it," the full irony

of his position comes to light, for historicity is exactly what he cannot ultimately

attribute to the knower. His insight into the historical nature of man seems to

have a purely negative value for him.

Against this background, we can now turn our attention to the new direction

Hans-Georg Gadamer takes in his reflections on the nature of understanding. In

his systematic work Truth and Method, which appeared in 1960, and in numer-

ous essays since that time,15 Gadamer elevates the historicity of understanding to

the level of a basic hermeneutical principle and exhibits the positive role his-

toricity actually plays in every human transmission of meaning. The most im-

mediate result of Gadamer's affirmation of historicity is to diminish the sharp

distinction between the scientific interpretation that goes on in the Geisteswissen-

schaften and the broader processes of understanding that occur everywhere in

human life without any pretense of scientific precision. Scientific interpretation

too, as a mode of human activity, is subject to the universal and binding power

of man's historicity. Quite explicit in Gadamer's work, therefore, is a thorough-

going critique of the excessive claims made by Dilthey and others that methodo-

logical self-consciousness and critical self-control amount to a vehicle whereby the

knower transcends his own historicity. Such claims reflect the Cartesian and

Enlightenment ideal of the autonomous subject who successfully extricates him-

self from the immediate entanglements of history and the prejudices that come

with that entanglement. For Dilthey, historical understanding occurs only in-

sofar as the knower breaks the immediate and formative influence of history

upon him and stands over against it. Historical understanding is the action of

subjectivity purged of all prejudices.

This methodological alienation of the knower from history is precisely the

point at which Gadamer focuses his criticism. Is it the case that the knower can

leave his immediate situation in the present by virtue of adopting an attitude?

1 Cf. Hans-Georg Gadamer, Wahrheit und Methode: Grundziige einer philosophischen

Hermeneutik (2nd ed.; Tiibingen: Mohr, 1965), and Kleine Schriften (3 vols.; Tiibingen:

Mohr, 1967-72). (The former work will be cited as WM, the latter as KS.) A selection

of essays from the Kleine Schriften, translated and edited by the present writer, will be

published shortly by Northwestern University Press as Essays in Philosophical Herme-

neutics.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 547

An ideal of understanding that as

ble only on the assumption that t

factor. But if it is an ontological

condition, then the knower's own

volved in any actual process of

knower's boundness to his presen

him from his object are no longe

come, but rather, the productive

do not cut us off from the past b

horizons have a hermeneutical sig

historical understanding commens

Precisely here is the point at whic

must critically begin. The overcomi

the Enlightenment - will itself tur

will clear the way for an appropria

only dominates our humanity but ju

standing in traditions actually mean

limited in one's freedom? Rather,

free - limited and conditioned in m

absolute reason is simply not a possi

is only real as historical, that is, wi

ways remains dependent upon the g

Prejudice is the necessary conditi

as a finite being, has no direct or

from his position in the present.

ined ways, the present is the "giv

and which reason can never entir

This is the meaning of the "herm

term. The givenness of the herm

critical self-knowledge in such fa

derstanding might disappear. "To

to be absorbed into self-knowledg

The past can now be seen to hav

of understanding. Its role cannot

or events that make up the "obje

tion, it also defines the ground th

stands. While acknowledging this

mer can still affirm the legitima

critical scholarship. Despite the a

receives its rightful and distingu

16 WM, p. 260.

17 WM, p. 285.

" Several reviewers have charged Ga

hostile and passionate of Gadamer's cr

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

548 DAVID E. LINGE

less, such methodology

broader more spon and

goes on and always has

scientific self-control.1

understanding tries to

and interpretation, or

knower's present histo

standing itself - even

tinues, and adds to the

to preserve and transm

formed at all without

immediately by the pa

in and through its und

form and have formed

derstanding, either bef

historical consciousnes

standing-within tradit

this. We can tell where

But Mommsen's Histor

methodology - also bet

ten and proves to be a

"knowing subject."''

In this fashion, Gadam

knowledge and traditio

which historical under

This continuing standin

situates the knower in

productive reality, of

seen this in the Phenom

arises from a histori

reason, Hegel contende

it into knowledge. Ga

Dilthey - to the extent

gaining critical awaren

stands in close proximity

der Geisteswissenschafte

is found in his "Hermcn

second edition of WM, p

"1 Gadamer has in mind

of art ( WM, pp. 1-162) a

290-95, 307-23). Cf. also, KS, I, pp. 101-107, 119-21.

' WM, p. 289.

2Cf. KS, I, pp. 103, 120-21.

22Cf. Hegel, Phianomenologie des Geistes (Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 1952), pp. 19ff.

(Baillie translation, pp. 80ff.), and Gadamer, WM, pp. 285-86.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 549

interaction which shapes our herm

historical interaction and the imme

all lead to the negation of its influ

ultimately of Dilthey's conceptio

equate these two--awareness of his

fluence upon us. For Gadamer, on

and finite, not absolute, and for th

"substantiality" of the past inoper

ing brings before me something

Something - but not everything, fo

torical interaction is inescapably m

never fully manifest."23 The con

negates the conditionedness. The r

of faith in a method does not cance

than does the naive unawareness of it.

It should be clear from this that Gadamer is not offering us a normative

account of historical understanding. He presents no new canon of interpreta-

tion, but rather is seeking to describe the ontological context in which all under-

standing - including critical understanding - transpires. This context cannot

be adequately grasped in terms of a model of historical understanding dominated

by the idea of a method. The emphasis upon method, in fact, blurs our sensitivity

to historical understanding as an event over which the interpreter does not

preside. Here Gadamer's philosophy joins Heidegger's attack on the "sub-

jectivism" of Western metaphysics, which has as its point of departure the self-

secured position of the knowing subject. Understanding is an event, a move-

ment of history itself in which neither interpreter nor text can be thought of as

an autonomous part. "Understanding itself," Gadamer argues, "is not to be

thought of so much as an action of subjectivity, but as the entering into an event

of transmission in which past and present are constantly mediated. This is what

must gain validity in hermeneutical theory, which is much too dominated by

the idea of a procedure, a method."24

In sharp contrast to Dilthey's model, Gadamer regards historical understand-

ing not as transposition, but as translation. Even in the most careful attempts

to grasp the past "as it really was," understanding remains essentially a mediation

of the past with the present. Understanding is not reconstruction, but integra-

tion. As translation, mediation, the interpreter's action belongs to and is of the

same nature as the substance of history which fills out the temporal gulf. For

this gulf, as the continuity of heritage and tradition, is precisely a process of

"presencings," that is, of mediations, through which the past already functions in

and shapes the interpreter's present. Historical understanding is always a con-

crete fusing of horizons (Horizontsverschmeltzung). The event of understand-

ing alters the horizons that existed beforehand. The text or events of the past

23KS, I, p. 127.

' WM, pp. 274-75.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

550 DAVID E. LINGE

speak anew in the lan

is enhanced and broa

overcome. This conc

critical interpretatio

rect them in our eff

longer to be regarde

free, absolute knowl

permanent, inflexibl

immersion in histori

the presupposition o

toricity is taken ser

position and becomes

indeed productive an

and fused with future

In truth the horizon o

as we must all constan

the understanding of

such testing as the las

shape at all without th

itself as there are his

understanding is alway

in themselves.... In th

there old and new gr

one or the other ever

The event of underst

genuinely learns som

This is a profoundly

much from Hegel, b

great distance betwe

continues the contem

him attains a final g

sure, this absolute g

takes place instead in

precisely this contem

a victim of the very

Man, this temporal cr

he works in time, by

objects. While under t

in lies the eternal contradiction between creative minds and the historical con-

sciousness. The former naturally try to forget the past and to ignore the better

in the future. But the latter lives in the synthesis of all times, and it perceives

in all individual creation the accompanying relativity and transience. This con-

tradiction is the silently born affliction most characteristic of philosophy today.ft

' WM, p. 289.

2 Dilthey, GS, V, p. 364; similarly, cf. GS, VIII, p. 225.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 551

Gadamer's philosophy is more

side of Hegel's thought. Not th

ing, dialectical life of reason fi

neutics. Historical understandin

knowledge.27 Every experience,

experience. Our efforts to un

Genuine historical understandin

our finitude. Yet this conscio

being - is not an achievement w

infinitude of absolute knowled

experience, for future historica

ity of historical interaction, th

rather contains, as an essential i

formation, that is, for fusion w

Gadamer has located the dee

Heidegger and has built upon i

event of understanding is both

ongoing dialogue with the past

only to be resumed again and a

like all new attempts at philos

evitable interinvolvement of dis

and disadvantages.

I have indicated that Gadamer

for interpretation, but seeks to

what is actually achieved in his

mer's philosophical hermeneutic

tology that more adequately illu

standing. Gadamer emphaticall

metaphysics and the consciousn

against the "subjectivism" of

standing of being that can push

ter of hermeneutical theory an

braces knower and known ali

act of subjectivity - as an adequ

tion of the original author (me

judged against an alleged mean

terpretations and is only throu

therefore, is extensive and epi

standing is a moment in the lif

are subordinate elements. It is e

going process of "presencing

present. "The real event of und

" Cf. WM, pp. 439-40.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

552 DAVID E. LINGE

beyond what can be

by methodological ef

what we ourselves ca

that through it some

Gadamer's philosoph

tion of the actual ro

should be of interes

from the ideal of on

of text or historical

situation is a constitu

is no meaning of the

But Gadamer's theor

stimulate further in

mer do away with th

himself to the charg

whatsoever and make

preter may well fin

final result of his ef

the process of traditi

of in all this." But ca

procedures he follow

determinate meanin

lar to that encounter

where a tension and

situation of ethical a

the objective, unamb

Like ethics, hermene

meaning and the cre

be that a theory of h

dialogue with ethics

linguistic analysis.

Perhaps Gadamer's t

question of the objec

through a careful de

actually come into co

conversation and agr

situation as one essen

What a text means is

stubbornly adhered to

the question of how

In this sense, underst

comprehension" whic

to understand the tex

' KS, I, pp. 80-81.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DILTHEY AND GADAMER 553

meaning of the text the interpre

extent, the interpreter's own hori

standpoint which one holds fast or c

and possibility which cooperates in

We have described this as a fusin

form of operation of the conversat

sion which is not only mine or my

However this may be, Gadamer

function of human historicity as

past for ever new concretizations

ing for ever new appropriations

2 WM, p. 366.

This content downloaded from

106.221.238.30 on Tue, 05 Dec 2023 05:04:59 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Esotericism and The Critique of HistoricismDocument18 pagesEsotericism and The Critique of HistoricismLovro KraljNo ratings yet

- Bracken Philosophy and RacismDocument20 pagesBracken Philosophy and RacismMark LeonardNo ratings yet

- Speech ActDocument14 pagesSpeech ActA. TENRY LAWANGEN ASPAT COLLE100% (2)

- Claudia Goldin-Career and FamilyDocument1 pageClaudia Goldin-Career and Familyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Core77 - 1000 Words - A Mani..Document2 pagesCore77 - 1000 Words - A Mani..mludwig8888No ratings yet

- Donald R. Kelley - Faces of History - Historical Inquiry From Herodotus To HerderDocument350 pagesDonald R. Kelley - Faces of History - Historical Inquiry From Herodotus To HerderJhon Edinson Cabezas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Scientific Discovery, Logic, and RationalityDocument388 pagesScientific Discovery, Logic, and RationalityIduán García100% (1)

- Zielinski, Siegfried - Deep Time of The Media. Toward An Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical MeansDocument391 pagesZielinski, Siegfried - Deep Time of The Media. Toward An Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical MeansNadia_Karina_C_9395No ratings yet

- Candy 2005 - Futures and GardeningDocument17 pagesCandy 2005 - Futures and GardeningStuart CandyNo ratings yet

- Foucault and The New HistoricismDocument17 pagesFoucault and The New HistoricismLovro KraljNo ratings yet

- Meaning in History: The Theological Implications of the Philosophy of HistoryFrom EverandMeaning in History: The Theological Implications of the Philosophy of HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Frank Ankersmit - Historicism. An Attempt at SynthesisDocument20 pagesFrank Ankersmit - Historicism. An Attempt at SynthesisEdmar Victor Guarani-Kaiowá Jr.No ratings yet

- Indiana University PressDocument33 pagesIndiana University Pressrenato lopesNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Theory and HistorismusDocument35 pagesAesthetic Theory and HistorismusMG BurelloNo ratings yet

- Hayden White and The Aesthetics of Histo PDFDocument20 pagesHayden White and The Aesthetics of Histo PDFMiguel ValderramaNo ratings yet

- Cbo9781139170291 004Document25 pagesCbo9781139170291 004Denilson XavierNo ratings yet

- Cbo9781139170291 003Document23 pagesCbo9781139170291 003Denilson XavierNo ratings yet

- American Historical Review: The History of IdeasDocument13 pagesAmerican Historical Review: The History of Ideasabimanyu setiawanNo ratings yet

- Are We All Greeks CartledgeDocument9 pagesAre We All Greeks CartledgemaxNo ratings yet

- Collins 1985Document10 pagesCollins 1985elfifdNo ratings yet

- Fowler, MYTHOS AND LOGOSDocument23 pagesFowler, MYTHOS AND LOGOSDe Grecia Leonidas100% (1)

- PDFDocument2 pagesPDFEsteban VediaNo ratings yet

- The Treatment of "Irrationality" in The Social SciencesDocument21 pagesThe Treatment of "Irrationality" in The Social SciencesHospodar VibescuNo ratings yet

- Tiner, Eschatology and PoliticsDocument24 pagesTiner, Eschatology and PoliticsRasoul NamaziNo ratings yet

- Cbo9781139170291 002Document24 pagesCbo9781139170291 002Denilson XavierNo ratings yet

- NonhistoryDocument10 pagesNonhistoryfloatingduckNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 195.251.6.2 On Wed, 05 Oct 2022 11:25:39 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.251.6.2 On Wed, 05 Oct 2022 11:25:39 UTCKostas TampakisNo ratings yet

- Historical Perspective: Using The Past To Study The Present: Academy of Management Review April 1984Document7 pagesHistorical Perspective: Using The Past To Study The Present: Academy of Management Review April 1984antonio jeovaniNo ratings yet

- Readings in Phil HistoryDocument3 pagesReadings in Phil HistoryHernandez, Christin A.No ratings yet

- Nowell SmithDocument29 pagesNowell SmithDenilson XavierNo ratings yet

- The Historical EventDocument27 pagesThe Historical EventMeenukutty MeenuNo ratings yet

- Empathy and History: Historical Understanding in Re-enactment, Hermeneutics and EducationFrom EverandEmpathy and History: Historical Understanding in Re-enactment, Hermeneutics and EducationNo ratings yet

- William Beik - The Dilemma of Popular CultureDocument10 pagesWilliam Beik - The Dilemma of Popular CultureFedericoNo ratings yet

- Braudel1960 2Document12 pagesBraudel1960 2Leticia ZuppardiNo ratings yet

- Retz, 2015. A Moderate Hermeneutical Approach To Empathy in History Education PDFDocument14 pagesRetz, 2015. A Moderate Hermeneutical Approach To Empathy in History Education PDFNATALIA CONSTANZA ALBORNOZ MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- 00 WILHELM DILTHEY - On Interpretation - I - The Rise of Hermeneutics (New Literary History, Vol. 3, Issue 2) (1972)Document17 pages00 WILHELM DILTHEY - On Interpretation - I - The Rise of Hermeneutics (New Literary History, Vol. 3, Issue 2) (1972)marcus winterNo ratings yet

- Wiley Wesleyan UniversityDocument13 pagesWiley Wesleyan Universityjhonaski riveraNo ratings yet

- Appleby, Telling The Truth About History, Introduction and Chapter 4Document24 pagesAppleby, Telling The Truth About History, Introduction and Chapter 4Steven LubarNo ratings yet

- Roseberry - Balinese Cockfights and The Seduction of AnthropologyDocument17 pagesRoseberry - Balinese Cockfights and The Seduction of AnthropologyEsteban RozoNo ratings yet

- The End of HistoryDocument26 pagesThe End of Historykafka717No ratings yet

- Hegel's Philosophy of HistoryDocument12 pagesHegel's Philosophy of HistoryArch Mustafa SaadiNo ratings yet

- HT A History of The FutureDocument19 pagesHT A History of The FutureEdvardas ŠlikasNo ratings yet

- 3 Reason and Decision-MakingDocument42 pages3 Reason and Decision-MakingCarolina PaezNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and Social ChangeDocument14 pagesPhilosophy and Social Changecauim.ferreiraNo ratings yet

- Elías José Paltí - Historicism As An Idea and As A LanguageDocument11 pagesElías José Paltí - Historicism As An Idea and As A LanguageTextosNo ratings yet

- 12 - Skoric - Beslin 2017-3Document20 pages12 - Skoric - Beslin 2017-3vojvodjanski.klub92No ratings yet

- Two Approaches To Historical Study: The Metaphysical (Including 'Postmodernism') and The HistoricalDocument32 pagesTwo Approaches To Historical Study: The Metaphysical (Including 'Postmodernism') and The HistoricalDavid HotstoneNo ratings yet

- Ankers M It 1990Document23 pagesAnkers M It 1990alexNo ratings yet

- HIRSCH, E. STEWART, C. Ethnographies of HistoricityDocument15 pagesHIRSCH, E. STEWART, C. Ethnographies of HistoricityAnonymous M3PMF9iNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press University of Notre Dame Du Lac On Behalf of Review of PoliticsDocument22 pagesCambridge University Press University of Notre Dame Du Lac On Behalf of Review of PoliticsXimena U. OdekerkenNo ratings yet

- Shklar - Rethinking The PastDocument12 pagesShklar - Rethinking The PastNicolasDiNataleNo ratings yet

- An Ethnologist's View of History An Address Before the Annual Meeting of the New Jersey Historical Society, at Trenton, New Jersey, January 28, 1896From EverandAn Ethnologist's View of History An Address Before the Annual Meeting of the New Jersey Historical Society, at Trenton, New Jersey, January 28, 1896No ratings yet

- Philosophical Review - Humanistische Reden Und Vorträgeby Werner JaegerDocument4 pagesPhilosophical Review - Humanistische Reden Und Vorträgeby Werner JaegerHamidNo ratings yet

- História Dos Arquivos ModernosDocument8 pagesHistória Dos Arquivos ModernosFelipe MamoneNo ratings yet

- Susan-Buck-Morss - The Gift of The PastDocument13 pagesSusan-Buck-Morss - The Gift of The PastjazzglawNo ratings yet

- Faubion HistoryAnthropology 1993Document21 pagesFaubion HistoryAnthropology 1993ataripNo ratings yet

- Assignment in ReadingsDocument3 pagesAssignment in ReadingsMishaSamantha GaringanNo ratings yet

- Goldstein Collingwood's Theory of Historical KnowingDocument35 pagesGoldstein Collingwood's Theory of Historical KnowingRadu TomaNo ratings yet

- Assis Objectivity in History 2020Document22 pagesAssis Objectivity in History 2020rebenaqueNo ratings yet

- 6a-Recent Scholarship On History and MemoryDocument17 pages6a-Recent Scholarship On History and Memoryzelycia amundariNo ratings yet

- Historical Perspective: Using The Past To Study The Present: The Academy of Management Review April 1984Document7 pagesHistorical Perspective: Using The Past To Study The Present: The Academy of Management Review April 1984Stanzin PhantokNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 195.33.244.114 On Sun, 20 Mar 2022 16:49:32 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.33.244.114 On Sun, 20 Mar 2022 16:49:32 UTCZübeyde GürboğaNo ratings yet

- Polimenov, T. - A Review of Khristo Todorov's Essays On The Philosophie of HistoryDocument4 pagesPolimenov, T. - A Review of Khristo Todorov's Essays On The Philosophie of HistoryAntonia Polimenova-TsonevaNo ratings yet

- WWW Historytoday Com Stefan Collini What Intellectual HistoryDocument20 pagesWWW Historytoday Com Stefan Collini What Intellectual HistoryAnonymous X40FqoDiCNo ratings yet

- Archana Prasad-Integrated Farm Solutions and its Impact on Small Farmers A Case Study of Bayer in Karnal, Haryana, GPN Working Paper NumbeDocument90 pagesArchana Prasad-Integrated Farm Solutions and its Impact on Small Farmers A Case Study of Bayer in Karnal, Haryana, GPN Working Paper Numbeanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Changing contours of solid waste management in IndiaDocument11 pagesChanging contours of solid waste management in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Neoliberal Subjectivity, Enterprise Culture and New Workplaces: Organised Retail and Shopping Malls in IndiaDocument10 pagesNeoliberal Subjectivity, Enterprise Culture and New Workplaces: Organised Retail and Shopping Malls in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- MSMEs Introduction-Rashmi ChaudharyDocument46 pagesMSMEs Introduction-Rashmi Chaudharyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Gandhi and MSMEsDocument9 pagesGandhi and MSMEsanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Display PDF - PHPDocument21 pagesDisplay PDF - PHPanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Praveen Jha-Labour Condition in Rural IndiaDocument134 pagesPraveen Jha-Labour Condition in Rural Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- ARC - Jobless Growth & Labour Conditions in IndiaDocument22 pagesARC - Jobless Growth & Labour Conditions in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Santosh Mehrotra-InformalityDocument24 pagesSantosh Mehrotra-Informalityanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Content Server 1Document25 pagesContent Server 1anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Agrarian Question of Capital and LabourDocument35 pagesAgrarian Question of Capital and Labouranshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Contemporary Globalisation and Value Systems What Gains For Developing Countries by Jha and YerosDocument15 pagesContemporary Globalisation and Value Systems What Gains For Developing Countries by Jha and Yerosanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Disposable People-Kelvin BalesDocument12 pagesDisposable People-Kelvin Balesanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Law and COntradictionsDocument13 pagesLaw and COntradictionsanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Barbara Harris Whita and Henry Bernstein-Reviewing-Petty-Commodity-Production-Toward-A-Unified-Marxist-ConceptionDocument9 pagesBarbara Harris Whita and Henry Bernstein-Reviewing-Petty-Commodity-Production-Toward-A-Unified-Marxist-Conceptionanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Harriss WhiteDocument38 pagesHarriss Whiteanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Property 1Document1 pageProperty 1anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- CI 403 Monsoon 2023Document4 pagesCI 403 Monsoon 2023anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- The Harris - Todaro Model of Labour Migration and Its Implication in Commercial Policy ImplicationDocument101 pagesThe Harris - Todaro Model of Labour Migration and Its Implication in Commercial Policy Implicationanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Problem Set 1Document1 pageProblem Set 1anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Employment Plfs 201718Document9 pagesEmployment Plfs 201718anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Amiya Kumar Bagchi - Chapter 13Document13 pagesAmiya Kumar Bagchi - Chapter 13anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Conceptually and EmpiricallyDocument11 pagesConceptually and Empiricallyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Global Value Chain-EPWDocument8 pagesGlobal Value Chain-EPWanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- N.Neetha-Data and Data Systems in Unpaid WorkDocument11 pagesN.Neetha-Data and Data Systems in Unpaid Workanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes Chapter 7 Exercises and AnswersDocument102 pagesLecture Notes Chapter 7 Exercises and AnswersAbhipsaNo ratings yet

- Mol, A - The Environmental State and Environmental GovernanceDocument24 pagesMol, A - The Environmental State and Environmental GovernancePauloNo ratings yet

- Module 5 PhiloDocument4 pagesModule 5 Philogirlie jimenezNo ratings yet

- الفقر وعلاقته بالعوامل الاقتصادية والاجتماعية والديموغرافية في الجزائرDocument14 pagesالفقر وعلاقته بالعوامل الاقتصادية والاجتماعية والديموغرافية في الجزائرHnan SaidNo ratings yet

- attachmentsff33a8a91029original3020Manipulation20Techniques PDFDocument64 pagesattachmentsff33a8a91029original3020Manipulation20Techniques PDFHussain BahaNo ratings yet

- Assignment / TugasanDocument15 pagesAssignment / TugasantEnG pArThIbAnNo ratings yet

- Lec3 Types of ResearcheDocument26 pagesLec3 Types of ResearcheALI Al malahiNo ratings yet

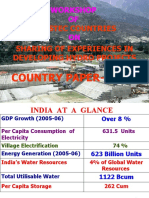

- Bimstec Countries Sharing of Experiences in Developing Hydro ProjectsDocument30 pagesBimstec Countries Sharing of Experiences in Developing Hydro Projectsjaiganeshmails100% (1)

- Onomatopoeia in HebrewDocument18 pagesOnomatopoeia in Hebrewsamuel fernandesNo ratings yet

- Nature, in The Broadest Sense, Is The: PhysisDocument1 pageNature, in The Broadest Sense, Is The: PhysisAkshatNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Infrastruktur Secara Spasial Terhadap Konvergensi Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Di IndonesiaDocument12 pagesPengaruh Infrastruktur Secara Spasial Terhadap Konvergensi Pertumbuhan Ekonomi Di IndonesiaLaksmiTitisAstrytaDewiNo ratings yet

- Hughes10e PPT Ch01Document33 pagesHughes10e PPT Ch01Azin RostamiNo ratings yet

- W9 Niobe WayDocument12 pagesW9 Niobe WayLuth JardinelNo ratings yet

- Oppressed Women's Voices and Female Writing in Sylvia Plath's "Tulips" and "Daddy"Document5 pagesOppressed Women's Voices and Female Writing in Sylvia Plath's "Tulips" and "Daddy"Emily ChenNo ratings yet

- Gender & Society: BELIEVING IS SEEING:: Biology As IdeologyDocument15 pagesGender & Society: BELIEVING IS SEEING:: Biology As IdeologyAurélio OliveiraNo ratings yet

- PERDEVELPMENTDocument19 pagesPERDEVELPMENTAlliana O. BalansayNo ratings yet

- Who Are The Indigenous PeopleDocument7 pagesWho Are The Indigenous PeopleFrancisNo ratings yet

- Reviewer LLLDocument5 pagesReviewer LLLJazzi ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Essay "The Role of Pancasila in Building and Maintaining The Unity of Indonesia" Name: Resyalwa Azzahra Harahap Nim: 2203321009 Class: DIK F 20Document1 pageEssay "The Role of Pancasila in Building and Maintaining The Unity of Indonesia" Name: Resyalwa Azzahra Harahap Nim: 2203321009 Class: DIK F 20Resyalwa Azzahra HarahapNo ratings yet

- Biomassa e Energia PDFDocument6 pagesBiomassa e Energia PDFannesuellenNo ratings yet

- Blog 1 Week 2 ContentDocument14 pagesBlog 1 Week 2 ContentSKITTLE BEASTNo ratings yet

- Summative Assessment Things Fall ApartDocument4 pagesSummative Assessment Things Fall Apartapi-428944081No ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior Key Concepts Skills and Best Practices 5th Edition Kinicki Test BankDocument35 pagesOrganizational Behavior Key Concepts Skills and Best Practices 5th Edition Kinicki Test Bankdianelambkqvbvt100% (23)

- Chapter 3Document7 pagesChapter 3Niles VentosoNo ratings yet

- Linguistics 3rd YearDocument19 pagesLinguistics 3rd YearThe hopeNo ratings yet

- Emile Boutroux, Fred Rothwell, Translator - Historical Studies in Philosophy (1912) PDFDocument358 pagesEmile Boutroux, Fred Rothwell, Translator - Historical Studies in Philosophy (1912) PDFSila MitridatesNo ratings yet