Professional Documents

Culture Documents

21_Culture

Uploaded by

Hani BoudiafCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

21_Culture

Uploaded by

Hani BoudiafCopyright:

Available Formats

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Table of Contents

Session plan ........................................................................................................................ 2

Culture ................................................................................................................................. 3

Introduction to culture ............................................................................................... 3

Aviation Culture .......................................................................................................... 5

National Culture ......................................................................................................... 6

Cultural dimension in aircraft accidents .................................................................. 7

National culture – Basic premise ............................................................................. 8

Professional culture ................................................................................................. 11

Company culture ...................................................................................................... 12

Safety culture and CRM ........................................................................................... 13

Pilots vs Cabin crew – Same culture? .................................................................... 13

Boeing vs Airbus ....................................................................................................... 14

Military vs Commercial Flying Culture..................................................................... 15

Type of Flying Operations ........................................................................................ 16

Managing cultural differences & CRM training ...................................................... 17

Developing the right culture .................................................................................... 18

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.1

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Module 21

Culture

Session plan

Module no 21

Module title Culture

Duration 1 hour

Optimal class size 6 to 12

Learning On completion of the module the student will be able to:

Objectives

• Identify the different cultures which are present in our professional aviation

environment

• List ways in which to develop and maintain an appropriate organisational and

positive safety culture

Delivery method Facilitation

Trainer Trainer to have completed 5 day CRM Trainer core course.

qualifications

Student None

prerequisites

Trainer materials PowerPoint

Whiteboard

Flipchart

Participant Handout: N/A

materials

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.2

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Culture

Slide – Header slide

Introduction to culture

Slide – Introduction

Slide – Introduction

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.3

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Slide – Introduction

Professor Geert Hofstede, a Dutch, social psychologist, who is notable in his research of

cross-cultural groups and organisations defines culture as;

“The collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or

category of people from others.”

Slide – Background

Culture surrounds us and influences the values, beliefs, and behaviours that we share with

other members of groups. Culture serves to bind us together as members of groups and to

provide clues and cues as to how to behave in normal and novel situations.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.4

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Aviation Culture

Slide – Background

When thinking of culture, what typically comes to mind first is national culture, the

attributes that differentiate between natives of one culture and those of another.

For pilots and cabin crew however, there are three cultures operating to shape actions and

attitudes.

▪ National culture (Global Workplace).

▪ Professional culture that is associated with being a member of the pilot

profession.

▪ Company (organisational) culture – which defines the daily activities of

their members.

All three cultures are of importance in an aviation environment because they influence

critical behaviours. These include how junior crew relate to their seniors and how

information is shared. Culture can also shape attitudes about stress (e.g. gung ho/macho

or supportive) and personal capabilities. It also influences adherence to SOPs and how

automation is valued and used.

Each of the three cultures has strengths that enhance safety and weaknesses which can

diminish it.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.5

MODULE 21

CULTURE

National Culture

Slide – National Culture

People who have grown up in different countries will have experienced different general

ways of acting and behaving, particularly in social situations. They will also have developed

different values. A person from one country might act in a way that seems polite, but a

person from a different country might perceive that way of acting as rude.

In an increasing global workplace of multicultural and multilingual working environments a

junior, assertive Western FO, who’s culture values subordinates speaking up, goes against

cultural norms in an Eastern Flight deck were they value subordinates who obey their

superiors unquestioningly, can be damaging to a working dynamic; as the Captain

perceives the FO as being impolite, aggressive or disruptive which will lead to a less

functional (and possibly less safe) environment.

In his study of national culture and CRM, Aviation Psychologist Brent Hayward (1997)

compared the implicit meanings present in language despite the same explicit

communication. For example, the word yes to a Westerner is an acknowledgment and

agreement with another party. However, the same word, to an East Asian can be just an

acknowledgement without any intent to express agreement.

This misunderstanding of implicit information can lead to faulty situation awareness and

decision-making, which can impact aviation safety. In addition, although English is the

universal language for aviation, most cultures have a different accent and use of it. This

slows crew co-ordination and causes further misunderstandings.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.6

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Slide – National Culture

As well as Communication and common language other cultural differences include:

▪ Humour

▪ Religion

▪ Politics

▪ Use of automation

These differences in culture can create friction between individuals slowing teamwork and

decision-making also decreasing one another’s trust.

Cultural dimension in aircraft accidents

Whereas accident rates vary among nations (particularly between the developed and

developing world) it is not obvious to what extent, if any, those accident rates are

influenced by cultural differences (e.g. between developed and developing nations).

Nevertheless, some researchers have made convincing arguments attributing cultural

dimensions to accidents.

Slide – Culture in aircraft accidents

1) Asiana Airlines Flight 214, 6th July 2013 (4min 44sec video)

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.7

MODULE 21

CULTURE

http://www.voanews.com/content/aviation-experts-question-whether-culture-had-role-in-

asiana-crash/1730757.html

http://www.voanews.com/media/video/1731526.html

2) One example is argued by Helmrich (1994) to be the Avianca (Boeing 707) Flight 52

19th July 1989 that ran out of fuel approaching John F Kennedy Airport (the criticality of

the fuel emergency was not communicated by Spanish pilots).

3) Another, argued by Westrum and Adamski (1999) is the runway overrun of Korean Air

1533 (MD-83) 15th March 1999 in which there was disagreement between the Korean

and Canadian pilots.

4) Korean Air Cargo Flight 8509 (Boeing 747-2B5F) 22 December 1999 – from London to

Milan. The crew banked the aircraft into the ground while multiple audible warnings were

sounding. Subsequent investigation revealed that the pilots did not respond appropriately

to warnings during the climb after take-off despite prompts from the flight engineer. The

commanding pilot maintained a left roll control input, rolling the aircraft to approximately

90 of left bank and there was no control input to correct the pitch attitude throughout the

turn. The first officer either did not monitor the aircraft attitude during the climbing turn or,

having done so, did not alert the commander to the extreme unsafe attitude that

developed, and the maintenance activity at London/Stansted was misdirected.

Investigators subsequently suggested, among other things, that Korean Air alter training

materials and safety education to meet the "unique" Korean culture.

5 Helios Airways Flight 522 (737-300) 14th August 2005 - German Captain (history of

abrupt, distant, weak advocacy of teamwork) and Cypriot First Officer (history of not

following checklist and SOPs) all within an organisation which had barriers of personal

conflict, language, cultural traits with a lacklustre CRM training programme.

National culture – Basic premise

Slide – National Culture

Research of Hofstede (1980, 1991) laid the foundation for the considerable body of work

which has since examined the role of national culture in relation to flight crew behaviour

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.8

MODULE 21

CULTURE

and safety on the flight deck. In it he identified a number of dimensions were national

culture could be identified:

Power Distance (PD)

One’s perception of (and response to) hierarchy, seniority or rank.

In a high-power distance culture (e.g. India) the social inequality is accepted and leaders

are expected to be decisive and self-sufficient, while the subordinates should know their

place and not question their superiors. In a low power distance culture (e.g. Austria) all

citizens treat and view each other as team mates or colleagues there is no gap between

boss and employee, captain and co-pilot. This will affect the management, teamwork and

communication between the crew.

Individualism and collectivism (IND)

A reference to whether a person’s goals are self-oriented (individualism) or team-oriented

(collectivism).

Individualists cultures (e.g. US, Australia, Great Britain) view their actions in a narrow-

minded frameset of personal costs and benefits and group involvements are seen as costs

or rewards. In this culture independence and self-sufficiency are valued, individuals like to

express their own opinions, communication is direct and personal, feedback is precise and

always verbal. Emphasis is placed on resolving conflicts rather than simply agreeing.

Whereas in Collectivist Cultures (e.g. Iran, and many Asian and South American Countries)

individuals express concern for the implications of their actions towards the group, being a

part of a group is highly valued and you have obligations to your group. They also tend to

have a stronger acceptance of fate, tending to cause low stress levels. It is possible to

commonly link collectivism to a high-power distance in a culture because authority is rarely

challenged in a group orientated society.

Uncertainty avoidance (UA)

This is the extent to which people feel threatened in unfamiliar situations or conditions

and of one’s need for defined structures and procedures.

High uncertainty avoidance involves a preference for standard operating procedures

(SOPs), direct face-to-face communications and leaving as little as possible to chance. Low

uncertainty avoidance involves acceptance of high stress and higher exposure to risk as

part of the job, with more tolerance and flexibility.

In the flight deck this may affect how each pilot reacts to an emergency situation and how

each crew member embraces protocol. High uncertainty avoidance cultures (e.g. Latin

America, Latin Europe) are very emotional and expressive with loud voices and sweeping

gestures, they will feel more stressed at work with preference to Standard Operating

Procedures and a stable environment leaving as little as possible to chance and often

communication is very direct. The lowest uncertainty avoidance cultures (e.g. Most Anglo,

Nordic and Asian countries) uncertain situations and conditions are viewed as part of the

job or part of life, and individuals seem more tolerant and flexible.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.9

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Slide – National Culture

Masculine and feminine cultures

This division determines the feeling towards traditional male and female values. In the

flight crew this will affect how much value the men and women place in their working

relationship. In a masculine culture (e.g. Switzerland) there is a stronger gender

differentiation in which males are assertive, competitive and value wealth relative to the

female population. In feminine cultures (e.g. Norway) value in placed on the quality of life

and relationships, male and female populations generally value assertiveness,

competitiveness and wealth equally.

Long vs. short term orientation

This describes the individual cultures orientation towards the future and the present. This

does not have a major effect in aviation working culture but can create friction between

individuals. In long term orientated cultures (e.g. China) people are focused on future

goals and actions are taken to achieve these. Value is placed on an individual’s thrift and

perseverance. Where as in short term orientated cultures (e.g. US and NZ) one’s focus is

on fulfilling social obligations of the present, protecting one’s ‘face’ rather than a respect

for tradition.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.10

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Professional culture

Slide – Professional Culture - Positives

Work conducted by aviation psychologists Robert L Helmreich and Ashleigh C. Merrit

(1998) confirmed that pilots have an overwhelming liking for their job (even if they have a

passionate dislike for their organisation). They found pilots are proud of what they do and

retain their love of the work and are strongly motivated to do it well. This very positive

aspect of the culture of pilots is pride in their profession can help organisations work

toward safety and efficiency in operations.

Slide – Professional Culture - Negatives

However, it was found that professional culture of pilots also has a strong negative

component in a near-universal sense of personal invulnerability. In particular, how the

majority of pilots in all cultures feel that their decision-making is as good in emergencies

as normal situations, that their performance is not effected by personal problems, and

that they do not make more errors in situations of high stress. This misplaced sense of

personal invulnerability can result in a failure to utilise CRM practices as countermeasures

against error.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.11

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Slide – Professional Culture – Impact on safety

In their research paper ‘Culture, Error, and Crew Resource Management’, (Robert L.

Helmreich, John A. Wilhelm, James R. Klinect, & Ashleigh C. Merritt) showed graphically

some of the positive and negative influences of pilots’ professional culture on safety. As

the figure illustrates, positive components can lead to the motivation to master all aspects

of the job, to being an approachable team member, and to pride in the profession. On the

negative side, perceived invulnerability may lead to a disregard for safety measures,

operational procedures, and teamwork.

Company culture

Slide – Company culture

While national, vocational and work group cultures have an undeniable influence on

individual and group behaviour at work, organisational culture has the potential to have a

very significant direct impact on the safety performance of organisations. It is

organisational culture which ultimately shapes workers' perceptions of safety, the relative

importance placed on safety, and members' activities regarding safety (Merritt &

Helmreich, 1996a). A number of authors have provided rigorous discussion on the

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.12

MODULE 21

CULTURE

importance of an appropriate organisational safety culture and the role that human factors

expertise can play in establishing and maintaining appropriate cultural norms

Safety culture and CRM

Slide – Company culture & CRM

A company’s safety culture is inextricably linked with, but can be distinguished from its

organisational culture. A company culture will depend on factors such as the way in which

the organisation handles the often conflicting goals of safety and profitability, the trade-

offs between the two, and the level of demonstrated commitment to safety. It also

depends heavily on perceptions of the organisational communication styles, for example, if

an employee is concerned about the safety of a certain practice or procedure, are

channels open for that concern to be communicated to management. If so, how will

management respond? Is the flight safety department proactive or reactive?

Pilots vs Cabin crew – Same culture?

Slide – Company culture – Pilots v Cabin crew

Brent Hayward, in his research paper Culture, CRM and aviation safety, recognised that

within the aviation industry, there exist a range of sub-cultures which can be labelled as

occupational or work group cultures. Examples include the occupations of pilot, flight

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.13

MODULE 21

CULTURE

attendant, maintenance engineer, ramp, air traffic control, etc. While these aviation

professions commonly share various vocational norms, there are also significant

differences between their sub-cultures. For instance, pilots and flight attendants work

together as members of the same flight crew, but there are many differences between

them in terms of stereotypical characteristics and management styles for each group

within the organisation.

The cockpit/cabin crew interface research conducted by Chute and her co-workers at

NASA Ames (Chute, Wiener, Dunbar, & Hoang, 1996) analysed the nature of the jobs to

reveal some generalised differences in the demographics and roles of the two work

groups, and their origins, as depicted in Table below.

Boeing vs Airbus

Slide – Company culture – Boeing v Airbus

Within the two biggest aircraft manufacturers there is a culture that distinguishes one from

the other due to the significant differences between the two, in their operating

philosophies and basic systems architecture.

“If it’s not Boeing, I ain’t going” vs “If it’s not Airbus, just take a bus”

Boeing uses traditional controls, where the position of control column corresponds to

position of control surfaces and force on the control column corresponds to force on the

control surfaces. This means that the pilot has to adjust the trim manually when not using

autopilot.

Boeing aircraft leave ultimate control mostly to the pilot.

In flight, the Airbus side-stick input does not indicate desired position of control surfaces,

but desired wing loading and roll rate. The flight computer takes care of trimming the

aircraft for straight flight at current speed and balance, even when autopilot is not

engaged.

Airbus aircraft limit pilots' capabilities in situations that require extreme action to be taken;

the computer may prevent the pilot from pushing the plane past its safe ranges, which

could be necessary in case of an emergency.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.14

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Contrary to what a lot of people think, there aren’t two “camps” of pilot out there, with one

that swears by the Boeing camp and another loyal to Airbus. Although it is recognised that

a pilot might prefer one over the other, it is usually the case of whatever aircraft make they

have been used to. In addition, other factors such Airlines, seniority, bidding preferences,

pay and conditions, commuting options, quality of life/work balance companies etc,

usually determine which aircraft they fly. Whether it’s a Boeing or an Airbus is really

secondary.

Which is safer?

It may be argued that Airbus relies too heavily on automation and flight envelope

protection — under certain conditions, Airbus flight control software precludes manual

inputs from the crew entirely resulting in a statistical stalemate.

However, in determining the better design culture the pros and cons of both sides will

remain, however both plane-makers have endured scandals and controversies, from the

air data sensor malfunction that may have played a role in the 2009 Air France disaster

(Airbus), to the rudder design problems that caused at least two fatal 737 crashes

(Boeing).

As author and researcher Malcom Gladwell (2008) points out, Boeing and Airbus design

modern, complex airplanes to be flown by two equals. That works beautifully in low-power-

distance cultures [like the U.S., where hierarchies aren't as relevant]. But in cultures that

have high power distance, it’s very difficult.

"You are obliged to be deferential toward your elders and superiors in a way that would be

unimaginable in the U.S." he added. That's dangerous when it comes to modern airplanes,

said Gladwell, because such sophisticated machines are designed to be piloted by a crew

that works together as a team of equals, remaining unafraid to point out mistakes or

disagree with a captain.

Military vs Commercial Flying Culture

Slide – Company culture – Military v Commercial

Acceptable risk?

A typical commercial flight is a largely predictive environment. As there will always be a

known sequence of events and significant variations from the plan are rare. If unusual,

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.15

MODULE 21

CULTURE

unplanned events or emergencies occur the clear majority can be modelled in advance, or

already experienced in the past. Hence, detailed checklists and procedures are in place

with loss of additional resources available beyond the flight deck, (e.g. ATC, Operations,

Maintrol etc) which can assist crews in a successful outcome.

Within military flying, pilots deliberately place themselves in a high-risk environment, with

the peacetime or training ‘acceptable’ loss rate being zero. And whilst commercial pilots

also have to deal with the unexpected, the reality is that the airlines have been

enormously successful at largely ‘systemising’ the risk out of their operations.

It is recognised that within military pilots there is a ‘higher’ risk culture (compared to

Commercial aviation), which is managed by equipping their pilots with tools and

techniques to be able to still make decisions to deal with the unique situations they end

up facing. It is recognised, unlike commercial flying, that it is not possible to provide all the

solutions they are ever likely to face. So the aim is to equip military pilots with the ability to

reach safe solutions themselves.

As military pilots, safety or risk management is not simply a compliance exercise, or

something that is outsourced to a separate department; it’s owned by the operators.

However, if it can’t be done safely, or at least within agreed acceptable boundaries of risk,

then it can’t be done at all.

Conversion from Military to Civilian Commercial Flying

What are the challenges?

As an example, Korea’s authoritarian culture had previously reflected Korean Air’s hiring

and promotion policy that favoured former military fliers over civilians. Too often, the effect

had been friction (hierarchical cockpits, poor stunted communication) which hampered the

pilot teamwork needed to fly Western-built jets.

Type of Flying Operations

Slide – Company culture – Type of operation

Within aviation there are a number of varying types of Aircraft operations, For example,

Commercial and Public, Business (Corporate) and specialised operations (air taxi, medical,

police, security etc). Within each of these organisations, the culture adopted to satisfy the

demands and expectations of the differing types of operation will be different.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.16

MODULE 21

CULTURE

These cultural differences will need to be recognised by the organizations and appropriate

management SOPs, and countermeasures be incorporated to ensure the risks identified

are acceptable and managed accordingly, whilst still meeting company financial

performance and profitability.

Managing cultural differences & CRM training

Whilst CRM has succeeded in developing better flight crews, due to expansion of aviation

with multicultural and multilingual cockpits there is a need to ensure how CRM techniques

and principles (which are based upon the cultural values of western European society) are

adapted to bridge the gap that separate pilots and crew in language, professional

expectations and cultural interaction.

Answers how to tackle – Basic premises of advocacy, communication and inquiry,

Move from personalities to culture CRM training

Slide – Managing cultural differences

CRM training in the past, had used training from corporate management disciplines and

applied it to aviation to focus upon pilot’s personalities. The idea was that by recognising

your own and your work colleague’s personality traits you will be able to adapt your

behaviour to ensure you still work together as an effective team in maintaining a safe

flight.

However, over recent years it has become recognised that within CRM sessions pilots and

crews are reluctant and uncomfortable to openly discuss their perceived negative

personality traits with their peers.

Aviation psychologist, Robert L. Helmreich refers to additional studies that indicate no

reliable and consistent evidence that personality relates to accidents. However, what is

agreed is that pilots’ personalities should be emotionally stable, non-impulsive, agreeable

but assertive, and that cultural differences should be appreciated by all crew-members,

and where possible substituted for a professional culture. In particular, Crew Resource

Management training of an organization needs to be tailored to the culture of the specific

individuals receiving the training.

Trainers should encourage flight crewmembers to communicate clearly with each other.

Just as pilots have no problem asking ATC to “say again” or “please clarify” instructions,

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.17

MODULE 21

CULTURE

they should be unwilling to accept an instruction from an aircraft captain or a reply from a

first officer that is imprecise or unclear.

For example, in cultures of high power distance (e.g. India), a First Officer should receive

training that correcting or questioning the Captain is not so much concerned with

disrespecting the Captain, but more about preventing events down the line that (for

example) might lead to the Captain ‘losing face.’ A well designed training program should

be able to overcome many cultural barriers (Helmreich, 1999).

An organisation needs to support the CRMT in ensuring their employees recognise the

basic premises of national culture identified by Professor Geert Hofstede they must be

applied at the individual pilot level through a three-step developmental mode:

▪ Awareness — Be mindful that you cannot accurately profile another

crewmember simply because of assumptions about his or her national

culture or language.

▪ Knowledge — Incorporate the skills learned from your company’s formal

CRM courses and recognise key phrases and terms that will better

enable communication success and understanding of another’s

perceived strengths and weaknesses.

▪ Skill — Apply the lessons learned to your daily flying activities, and

recognise what works (and, more importantly, what does not) with your

colleagues.

Returning to the basics of early CRM will require trainers to incorporate explicit phrases —

the new idiom — for crewmembers of different primary languages and cultures to employ

when a message is ambiguous.

“Please confirm you would like me to perform the following procedure …” and “Your

instructions are not clear — please clarify …” are examples of procedural, word-specific

SOPs planned for the latest iteration of CRM.

Developing the right culture

Slide – Developing the right culture

What is the right culture – it is one that empowers subordinates by training them the

cognitive (SA and Decision Making) and interpersonal skills (Communication, team work,

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.18

MODULE 21

CULTURE

advocacy and inquiry which will enable them to take on additional responsibility when

circumstances call for it.

Behavioural Markers (Notechs)

Via the use of Behavioural Markers organisations are able to develop CRM knowledge,

skills and attitudes appropriate to the culture, which influence flight safety.

Specific Behavioural Markers need to be developed which are sensitive to the individual,

organisation and profession.

Specific behavioural techniques intended to enhance situation awareness and flight

safety, such as cross-checking and verification of communication, preparation, planning,

and vigilance, speaking up to express concerns, and sharing a mental model of the

situation are all means of reducing the likelihood of an error occurring or trapping an error

before it has an operational impact.

These behavioural markers then need to be continually evaluated and reinforced

throughout sim and line orientated training, line checks and company assessments.

Human error and TEM

Also important to the establishment of an appropriate safety culture is the recognition that

human error is unavoidable and that it is the responsibility of a mature organisation to

effectively manage that error. Ensuring non-punitive policies regarding everyday error.

Threat Error Management has been identified as a method of universal agreement across

ALL cultures, which along with behavioural markers a set of error countermeasures that

when applied reduces the likelihood of error, trapping errors before they have an

operational effect, and mitigating the consequences of errors when they do occur.

To summarise

Slide – Summary

Recognition of various cultures within the aviation industry will go a long way toward

mitigating the undesirable effects of some of those cultures, and breaking down barriers

between sub-cultures.

Development and maintenance of an appropriate organisational culture and a positive

safety culture is essential.

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.19

MODULE 21

CULTURE

Crew Resource Management training needs to be tailored to the culture of the specific

individuals receiving the training.

A well-designed training program should be able to overcome many cultural barriers.

References

Flight Safety Foundation David M. Bjellos – Multicultural CRM

http://flightsafety.org/aerosafety-world-magazine/august-2012/multicultural-CRM

University of Texas, Robert L. Helmreich, John A. Wilhelm, James R. Klinect, & Ashleigh C.

Merritt, 1 Culture, Error, and Crew Resource Management

University of Texas, Robert L. Helmreich, Building Safety on the Three Cultures of Aviation

Human Factors in complex sociotechnical systems, Liza Tam and Jacqueline Duley, Ph.D.

Booz Allen Hamilton McLean, VA BEYOND THE WEST: CULTURAL GAPS IN AVIATION

HUMAN FACTORS RESEARCH

Aviation Knowledge – National Culture in Aviation

http://aviationknowledge.wikidot.com/aviation:national-culture-in-aviation

The Australian Aviation Psychology Association, Brent Hayward, Culture, CRM and aviation

safety

CAA, CAP 737 – Flight-crew human factors handbook, October 2014

© Global Air Training Limited 2016 21.20

You might also like

- Risk Exposure: Expatriate Failure Under-PerformanceDocument31 pagesRisk Exposure: Expatriate Failure Under-PerformancePriya AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Ihrm (3,4,5)Document8 pagesIhrm (3,4,5)gopika premarajanNo ratings yet

- Fish Can't See Water: How National Culture Can Make or Break Your Corporate StrategyFrom EverandFish Can't See Water: How National Culture Can Make or Break Your Corporate StrategyNo ratings yet

- Lesson1 - The Contemporary World 1Document33 pagesLesson1 - The Contemporary World 1Lloyd bustriaNo ratings yet

- The Brain DrainDocument74 pagesThe Brain DrainJoydip ChandraNo ratings yet

- Education and Training for the Oil and Gas Industry: Localising Oil and Gas OperationsFrom EverandEducation and Training for the Oil and Gas Industry: Localising Oil and Gas OperationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- OHCHR Training Guide CRPD and OPDocument134 pagesOHCHR Training Guide CRPD and OPGlobal Justice Academy100% (1)

- Training and Development - An Introduction to Expatriate Cultural TrainingDocument88 pagesTraining and Development - An Introduction to Expatriate Cultural TrainingShanu JainNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural TrainingDocument11 pagesCross Cultural TraininganitikaNo ratings yet

- OECD Creativity Working PaperDocument46 pagesOECD Creativity Working PaperMark GleesonNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Training ReportDocument12 pagesCross Cultural Training Reportkaran aroraNo ratings yet

- Effective Strategies For Developing and Retaining International Teams...Document25 pagesEffective Strategies For Developing and Retaining International Teams...Faith jakeNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Business Competencies MAR038-6Document25 pagesIntercultural Business Competencies MAR038-6saheraurme0360No ratings yet

- Cro - Ranjeet Dilshan - 20201205 - 000074Document11 pagesCro - Ranjeet Dilshan - 20201205 - 000074ramanpreet kaurNo ratings yet

- Cultural Differences Must Be Evaluated by An Organisation When Competing in Global MarketsDocument5 pagesCultural Differences Must Be Evaluated by An Organisation When Competing in Global Marketsاسامه سنكرNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0925753515001381 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0925753515001381 Mainalibaba1888No ratings yet

- Multi-Cultural Factors in The Crew Resource Management EnvironmenDocument17 pagesMulti-Cultural Factors in The Crew Resource Management EnvironmenSergio RomeroNo ratings yet

- 3 Internationalization of HRDocument4 pages3 Internationalization of HRjakub.chvojkaNo ratings yet

- 77 M4nS 252 PDFDocument10 pages77 M4nS 252 PDFDeepak Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Diversity Awareness Presentation - ORGB193Document9 pagesDiversity Awareness Presentation - ORGB193Aditya SrivastvaNo ratings yet

- Mission Vision ObjectivesDocument4 pagesMission Vision ObjectivesMubaShir MaNakNo ratings yet

- Module Cruise 2021 Updated PDFDocument33 pagesModule Cruise 2021 Updated PDFKatrina Javier100% (1)

- Module 1 ORGANIZATION - STRUCTURE OF GLOBALIZATIONDocument7 pagesModule 1 ORGANIZATION - STRUCTURE OF GLOBALIZATIONkennethpcano32No ratings yet

- MNGT6583 International Business Experience China 2017Document27 pagesMNGT6583 International Business Experience China 2017ac hanNo ratings yet

- MNGT6583: International Business Experience China (Including Hong Kong)Document27 pagesMNGT6583: International Business Experience China (Including Hong Kong)mbs mbaNo ratings yet

- FINAL Dissertation Off2007Document46 pagesFINAL Dissertation Off2007Jamel BelaidNo ratings yet

- Education For The 21St Century: A South Australian Perspective G. SpringDocument22 pagesEducation For The 21St Century: A South Australian Perspective G. SpringgladysNo ratings yet

- Manuel2017 Article VocationalAndAcademicApproacheDocument11 pagesManuel2017 Article VocationalAndAcademicApproachearmanNo ratings yet

- AKEPT Proposal For Cultural Intelligence - 25022021Document10 pagesAKEPT Proposal For Cultural Intelligence - 25022021Dyzza SharafizaNo ratings yet

- 5os04 SummaryDocument45 pages5os04 Summaryhind idrisNo ratings yet

- International Training and Development: Preparing Employees for Global AssignmentsDocument64 pagesInternational Training and Development: Preparing Employees for Global AssignmentsEddie930922No ratings yet

- Risk management as a strategy for the preservation of cultural heritage in sciences and healthFrom EverandRisk management as a strategy for the preservation of cultural heritage in sciences and healthNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Policy DesignDocument13 pagesModule 2 Policy DesignNilton Dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Presented To Dr. Ayman MetwallyDocument11 pagesPresented To Dr. Ayman MetwallyOssama FatehyNo ratings yet

- International Human Resource ManagementDocument7 pagesInternational Human Resource ManagementvydehiNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity Manning Strategies and Management Practices in Greek ShippingDocument22 pagesCultural Diversity Manning Strategies and Management Practices in Greek ShippingLaurayb MyrzaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to IHRM challengesDocument19 pagesIntroduction to IHRM challengesSanyam AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Communication Guide - v2.5Document12 pagesCommunication Guide - v2.5Ed BoringNo ratings yet

- THE Contemporary World: Basic Concepts of GlobalizationDocument17 pagesTHE Contemporary World: Basic Concepts of GlobalizationJeric RepatacodoNo ratings yet

- Full Download International Business 15th Edition Daniels Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesFull Download International Business 15th Edition Daniels Solutions Manualzaridyaneb100% (41)

- Cultural Adaptability - An Indicator of Inclusive World Growth Tim SeroyDocument7 pagesCultural Adaptability - An Indicator of Inclusive World Growth Tim SeroyJames PutoNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full International Business 15th Edition Daniels Solutions Manual PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full International Business 15th Edition Daniels Solutions Manual PDFstuartstubbendeckz100% (9)

- Cross Cultural ReportDocument7 pagesCross Cultural ReportAnthony BurnsNo ratings yet

- Fazekas-Field SbSreviewofGermany 2013Document111 pagesFazekas-Field SbSreviewofGermany 2013yasmineNo ratings yet

- International Project Management: Leadership in Complex EnvironmentsFrom EverandInternational Project Management: Leadership in Complex EnvironmentsNo ratings yet

- Mastura Naz - Section 2Document17 pagesMastura Naz - Section 2Syed TajbirNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity Manning Strategiesand Management Practicesin Greek ShippingDocument34 pagesCultural Diversity Manning Strategiesand Management Practicesin Greek ShippingThanos DimouNo ratings yet

- Chap 004Document18 pagesChap 004Thu HàNo ratings yet

- ABR 311 Study Guide 2024Document45 pagesABR 311 Study Guide 2024mosianetshepo5No ratings yet

- Coaching Mentoring and Managing Breakthrough Strategies To Solve Performance Problems and Build WDocument22 pagesCoaching Mentoring and Managing Breakthrough Strategies To Solve Performance Problems and Build WeaglebrdNo ratings yet

- Factors, Benefits, Aims and Role of School Heads in GlobalizationsDocument6 pagesFactors, Benefits, Aims and Role of School Heads in GlobalizationsKibetfredrickNo ratings yet

- Katie Kirkby, MPH University of Oxford Aldineber Alzate, University of SussexDocument45 pagesKatie Kirkby, MPH University of Oxford Aldineber Alzate, University of SussexSebastian Jaramillo PiedrahitaNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis Fall Semester, 2008: "How Does Culture Influence Communication in Multicultural Teams inDocument67 pagesMaster Thesis Fall Semester, 2008: "How Does Culture Influence Communication in Multicultural Teams ineldociNo ratings yet

- Multinational Enterprises and IHRMDocument6 pagesMultinational Enterprises and IHRMfysallNo ratings yet

- Garbage In, Garbage Out..... : The International Maritime Human Element BulletinDocument8 pagesGarbage In, Garbage Out..... : The International Maritime Human Element BulletinmarinedgeNo ratings yet

- 6019SSL CW2Document18 pages6019SSL CW2Muhammad Salman KhanNo ratings yet

- APT2Document2 pagesAPT2Hani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FFS1 INIT BDocument2 pagesFFS1 INIT BHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FFS1 ADocument2 pagesFFS1 AHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FFS2 CDocument2 pagesFFS2 CHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FMS work BookDocument21 pagesFMS work BookHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FFS4 BDocument2 pagesFFS4 BHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- GFACHAPT3TRAE01Document2 pagesGFACHAPT3TRAE01Hani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FFS2 INIT BDocument2 pagesFFS2 INIT BHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Airbus Action Flow A330Document13 pagesAirbus Action Flow A330Hani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FSA work BookDocument30 pagesFSA work BookHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- FFS2 BDocument2 pagesFFS2 BHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- 14_AutomationDocument23 pages14_AutomationHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- 10_DecisionMakingDocument18 pages10_DecisionMakingHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Skill TestDocument1 pageSkill TestHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- 19_RunwayIncursionDocument13 pages19_RunwayIncursionHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- 17_IcingDocument16 pages17_IcingHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- 11 CommunicationDocument28 pages11 CommunicationHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Monitoring lapses RC_mitigation stratDocument3 pagesMonitoring lapses RC_mitigation stratHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- LeadershipDocument94 pagesLeadershipHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Corporate Airlines J32 Delegate HandoutDocument8 pagesCorporate Airlines J32 Delegate HandoutHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

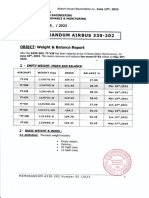

- MEMORANDUM AIRBUS A330-202 NUM 55 DATED June 13, 2023Document6 pagesMEMORANDUM AIRBUS A330-202 NUM 55 DATED June 13, 2023Hani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- NOTECHS Cats - Elements - EASA UpdateDocument7 pagesNOTECHS Cats - Elements - EASA UpdateHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- TRI_TRE_GuideDocument167 pagesTRI_TRE_GuideHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- 22_MonitoringinterventionDocument22 pages22_MonitoringinterventionHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Pinnacle CVR RecordsDocument7 pagesPinnacle CVR RecordsHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- SDV05Document11 pagesSDV05Hani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- 7TVJX Dah1012 20220902 Daag Daag F220902130744 4319267 0 9073Document101 pages7TVJX Dah1012 20220902 Daag Daag F220902130744 4319267 0 9073Hani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Brussels Airport Briefing ProceduresDocument137 pagesBrussels Airport Briefing ProceduresHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Cagm 6008 Vi PBCS Ads CPDLC Nat HlaDocument42 pagesCagm 6008 Vi PBCS Ads CPDLC Nat HlaHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Syllabi BDocument5 pagesSyllabi BHani BoudiafNo ratings yet

- Scale Aviation Modeller International - February 2020Document84 pagesScale Aviation Modeller International - February 2020Ron Lebert100% (2)

- Verma - Shashikant MR Del Hyd 2 MarDocument1 pageVerma - Shashikant MR Del Hyd 2 MarShashikant VermaNo ratings yet

- Dummies Guide To Flying The ME 109Document9 pagesDummies Guide To Flying The ME 109Mason ReyesNo ratings yet

- Heathrow Egll Pilot Operations Guide 2 0Document10 pagesHeathrow Egll Pilot Operations Guide 2 0Marcelo CameraNo ratings yet

- Safety Information Bulletin: Airworthiness - OperationsDocument4 pagesSafety Information Bulletin: Airworthiness - OperationsferbmdNo ratings yet

- MH370 - The Case of A Missing PlaneDocument3 pagesMH370 - The Case of A Missing PlaneSaurav BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Flight Management SystemDocument10 pagesFlight Management SystemSIMAR SINGH CHAWLANo ratings yet

- Atr72 Norm ProceduresDocument83 pagesAtr72 Norm Proceduresjuan romeroNo ratings yet

- Barros/Jorgemr 11sep Lis Ter: 1 MensagemDocument3 pagesBarros/Jorgemr 11sep Lis Ter: 1 MensagemrjiiNo ratings yet

- Defending America - Rules - BookletDocument24 pagesDefending America - Rules - BookletAquiles FragaNo ratings yet

- Sameer Bhikaji Pawar: Permanent AddressDocument2 pagesSameer Bhikaji Pawar: Permanent Addresssamepawar_76257301No ratings yet

- CPL BrochureDocument4 pagesCPL Brochureadam atomNo ratings yet

- Marek - 1-Junkers Ju-87BDocument11 pagesMarek - 1-Junkers Ju-87Bcastropereira100% (1)

- Airbus A220 Technical Training Manual - Airframe Bombardier CSeries CS300Document1,268 pagesAirbus A220 Technical Training Manual - Airframe Bombardier CSeries CS300Illarions Panasenko100% (19)

- Annexes 032-CQB Release 10Document21 pagesAnnexes 032-CQB Release 10Eliezer Planes100% (3)

- ItineraryDocument2 pagesItineraryArman AhmadiNo ratings yet

- WWII CAP Pilot Wings HistoryDocument2 pagesWWII CAP Pilot Wings HistoryCAP History Library100% (2)

- A350-900 Preliminary Data PDFDocument155 pagesA350-900 Preliminary Data PDFodehNo ratings yet

- Jeppesen weather briefing and NOTAMs for Phnom Penh International AirportDocument27 pagesJeppesen weather briefing and NOTAMs for Phnom Penh International Airportchang woo yunNo ratings yet

- Azores VuelosDocument4 pagesAzores VuelosfernanmataNo ratings yet

- MiG-29 v2.01 ManualDocument63 pagesMiG-29 v2.01 ManualDave91No ratings yet

- RAF Virtual Operations Manual 1.0Document6 pagesRAF Virtual Operations Manual 1.0HxmiiNo ratings yet

- E-Ticket flight booking from Chennai to HyderabadDocument2 pagesE-Ticket flight booking from Chennai to HyderabadAravindhan Gunasekaran PaediatricianNo ratings yet

- Dhaka, Bangladesh Vghs/Dac: 10-9 121.8 118.3 127.4 Hazrat Shahjalal IntlDocument1 pageDhaka, Bangladesh Vghs/Dac: 10-9 121.8 118.3 127.4 Hazrat Shahjalal IntlRitwik ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Dani TicketDocument2 pagesDani TicketAshar AwanNo ratings yet

- 5 Elements of The Aviation Ecosystem That Will Impact The Future of The Industry - Connected Aviation TodayDocument4 pages5 Elements of The Aviation Ecosystem That Will Impact The Future of The Industry - Connected Aviation TodayToto SubagyoNo ratings yet

- Spicejet Brand ManagementDocument18 pagesSpicejet Brand ManagementArpita MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- ICAO SAT/19 Meeting Discusses AF447 Report Safety RecommendationsDocument3 pagesICAO SAT/19 Meeting Discusses AF447 Report Safety RecommendationsJoão Hiller SilvaNo ratings yet

- Chengdu J-XX (J-20) Stealth Fighter PrototypeDocument25 pagesChengdu J-XX (J-20) Stealth Fighter PrototypeSanye PerniaNo ratings yet

- Singapore Air Lines 9GSIA19J03: InstructionsDocument5 pagesSingapore Air Lines 9GSIA19J03: InstructionsTrịnh Xuân BáchNo ratings yet