Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rearranging The Deck Chairs? A Critical Examination of Canada'S Shifting (Im) Migration Policies

Rearranging The Deck Chairs? A Critical Examination of Canada'S Shifting (Im) Migration Policies

Uploaded by

waciy70505Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rearranging The Deck Chairs? A Critical Examination of Canada'S Shifting (Im) Migration Policies

Rearranging The Deck Chairs? A Critical Examination of Canada'S Shifting (Im) Migration Policies

Uploaded by

waciy70505Copyright:

Available Formats

CITC - March 2010_3:Layout 1 26/03/10 5:31 PM Page 25

REARRANGING THE DECK

CHAIRS? A CRITICAL

EXAMINATION OF

CANADA’S SHIFTING

(IM)MIGRATION POLICIES

ABSTRACT

This article explores the recent shifts in directions in immigration policy, from nation builders (permanent residents)

to economic units (temporary workers), in response to the challenge of matching the selection process to the labour

market and the labour market’s failure to fully utilize many of Canada’s more skilled immigrants. Through an

exploration of some of the policy changes that have taken place in Canada over the past 10 years, and the reasons

policies have shifted, this article concludes that (im)migration policies are being revised and changed to address

problems that are not fully understood. Without proper evaluation of current and past policies, such policy changes

blur our understanding of where the gaps and issues lie in the system and how to address the real needs.

Immigrants as nation builders

C

anada has often been described as a nation of immigrants. In 2007, nearly 20% of the country’s

population was born outside of Canada, and each year about 240,000 immigrants arrive with

University of Guelph in International Development, Gender Studies and Sociology.

MA Program in Immigration and Settlement Studies and holds a BAH from the

in Toronto (www.wes.org/ca). Sophia graduated from Ryerson University’s

Sophia is the research and policy analyst at World Education Services (WES)

SOPHIA J. LOWE

permanent residence status (0.72% of the population) (CIC 2007a). It is projected that by

2012, all of Canada’s net labour market growth will come from immigration, and that by 2030, all of

its population growth will be due to immigration (HRSDC 2007).

The original immigration points system of 1967 was revised in 2002 under the Immigration and

Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), with the premise that in a knowledge-based economy, with a rapidly

changing labour market, it would be too difficult to match people’s skills with specific occupations in

demand. The revised and current points system (which has changed again with Bill C-50) is based on

the human capital model that assesses immigrants’ potential ability to establish themselves successfully

through high levels of education, training, experience and language skills. Essentially, it rewards

immigrants with the generic skills expected to allow them to adapt in a changing labour market.

Immigrants to Canada come from all over the world, with top-source countries being China (14%),

India (11.6%), Philippines (7%) and Pakistan (5.2%). Over 70% of all working age (15 to 65 years of age)

immigrants in the recent past hold some post-secondary education (Statistics Canada 2007b, 2007a).

Specifically, economic immigrants enter Canada based on their educational credentials, work experience

and language abilities (Statistics Canada 2007a) 92% of which have a post-secondary education (CIC

2007a).1 Expecting that the very education and skills that got them into Canada would be utilized, many

immigrants are deeply disappointed once they arrive and face only limited prospects for success.

Poor employment outcomes

Despite the high education levels of immigrants to Canada, many immigrants are underemployed

and unemployed, while highly skilled jobs remain vacant. In 2006, the unemployment rate of very recent

university educated immigrants was four times that of the university educated Canadian born and in

Ontario, the unemployment rate of all immigrants was 2.5 times higher than that of Canadian born

Ontarians (11% vs. 4.4%) (Gilmore 2008). Further, very recent university educated immigrants had an

unemployment rate similar to very recent immigrants holding only high school education (Zietsma

2007). Immigrant communities are facing greater incidences of poverty, despite having higher levels of

education than Canadian-born; and labour market outcomes for immigrants are only improving

marginally with time in Canada (Statistics Canada 2007b). Some of the major barriers faced by recent

immigrants are lack of foreign credential recognition, language barriers, lack of Canadian experience

and employment and racial discrimination (Statistics Canada 2005).

25

You might also like

- 30RH & 32RH Automatic TransmissionDocument90 pages30RH & 32RH Automatic Transmissionapi-26140644100% (15)

- SOP For Quality Risk Management - Pharmaceutical GuidelinesDocument3 pagesSOP For Quality Risk Management - Pharmaceutical Guidelinessakib44586% (7)

- Housing Finance Mechanisms in IndiaDocument61 pagesHousing Finance Mechanisms in IndiaUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)100% (2)

- James E. Miller Jr. J.D. Salinger University of Minnesota Pamphlets On American Writers 1968Document49 pagesJames E. Miller Jr. J.D. Salinger University of Minnesota Pamphlets On American Writers 1968Aurelia Martelli100% (1)

- Amazon IncDocument15 pagesAmazon Incabdul basitNo ratings yet

- Gu 2020Document21 pagesGu 2020Tasnim MuradNo ratings yet

- Internal Mobility and Likelihood of Skill Losses in Localities of EmigrationDocument24 pagesInternal Mobility and Likelihood of Skill Losses in Localities of Emigrationahmed_driouchiNo ratings yet

- Karnataka State StudyDocument18 pagesKarnataka State StudyVishwanath PatilNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 5 The Foreign Worker in Workplace DiversityDocument7 pagesCHAPTER 5 The Foreign Worker in Workplace Diversityliyanglindil13No ratings yet

- Issues Related Migration in IndiaDocument16 pagesIssues Related Migration in IndiarishiNo ratings yet

- Human Capital Spillovers From Special Economic ZonDocument15 pagesHuman Capital Spillovers From Special Economic ZonDung NguyenNo ratings yet

- GDLab Brochure Call For Research Proposals (ENG)Document9 pagesGDLab Brochure Call For Research Proposals (ENG)Igor DantasNo ratings yet

- Migration, Labour Market and Health ProtectionDocument37 pagesMigration, Labour Market and Health Protectionsubramanian kNo ratings yet

- The Labor Market Effects of IMMIGRATION: A Unified View of Recent Development by Giovanni PeriDocument7 pagesThe Labor Market Effects of IMMIGRATION: A Unified View of Recent Development by Giovanni PeriCatherine R. IronsNo ratings yet

- China's Hukou System: Overview, Reform, and Economic ImplicationsDocument3 pagesChina's Hukou System: Overview, Reform, and Economic ImplicationsSCRBDusernmNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Net Advantage or Disadvantage of Immigrants 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: Net Advantage or Disadvantage of Immigrants 1otieno vilmaNo ratings yet

- Harris Todaro 1970Document18 pagesHarris Todaro 1970galuhNo ratings yet

- The International Journal of Human Resource ManagementDocument18 pagesThe International Journal of Human Resource ManagementIvandi RachmatNo ratings yet

- 05 Immigration Greenstone LooneyDocument12 pages05 Immigration Greenstone LooneyAnuar Hurtado GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Wider Economic Impacts of High-Skilled Migrants: A Survey of The Literature For Receiving CountriesDocument20 pagesThe Wider Economic Impacts of High-Skilled Migrants: A Survey of The Literature For Receiving CountriesthawesgarNo ratings yet

- Understanding Migration Motives and Its Impact On Household Welfare Evidence From Rural Urban Migration in IndonesiaDocument16 pagesUnderstanding Migration Motives and Its Impact On Household Welfare Evidence From Rural Urban Migration in Indonesiamulifa iyahNo ratings yet

- BR Fing: The Case For Treating Long-Term Urban Idps As City ResidentsDocument4 pagesBR Fing: The Case For Treating Long-Term Urban Idps As City ResidentsJagadish JagsNo ratings yet

- Emerging Pattern and Trend of Migration in Megacities: Special ArticleDocument6 pagesEmerging Pattern and Trend of Migration in Megacities: Special Articlepragya guptaNo ratings yet

- PlazaDocument7 pagesPlazaSelwynVillamorPatenteNo ratings yet

- Hyper'-Urbanisation and Migration - A Security ThreatDocument5 pagesHyper'-Urbanisation and Migration - A Security Threat03 Akshatha NarayanNo ratings yet

- PWC India Surging To A Smarter FutureDocument32 pagesPWC India Surging To A Smarter Futureektasharma123No ratings yet

- M C - A, K. B N, A B, M W - R: Immigrant Employment Integration in Canada: A Narrative ReviewDocument20 pagesM C - A, K. B N, A B, M W - R: Immigrant Employment Integration in Canada: A Narrative ReviewPhạm Thùy TrangNo ratings yet

- Dejene 2nd Proposal Draft22334 With TrackDocument45 pagesDejene 2nd Proposal Draft22334 With Trackabdulmejidjemal1No ratings yet

- In and Out of The Ethnic Economy A Longitudinal Analysis of Ethnic Networks and Pathways To Economic Success Across Immigrant CategoriesDocument53 pagesIn and Out of The Ethnic Economy A Longitudinal Analysis of Ethnic Networks and Pathways To Economic Success Across Immigrant Categories11No ratings yet

- Creative Revision 1Document2 pagesCreative Revision 1api-457875809No ratings yet

- 2015 1 PDFDocument32 pages2015 1 PDFDaniel SherwoodNo ratings yet

- Kim 2021 Changes in The Distribution of Migrant Labourers and Implications of Comprehensive Wealth in China SDocument23 pagesKim 2021 Changes in The Distribution of Migrant Labourers and Implications of Comprehensive Wealth in China SJunyu MengNo ratings yet

- Rural-Urban Migration in Developing CountriesDocument13 pagesRural-Urban Migration in Developing Countriesan570No ratings yet

- Cash Transfers, Social ProtectionDocument10 pagesCash Transfers, Social ProtectionRahmat PasaribuNo ratings yet

- Grade 4/5: Week 19: Feb 8-11, 2020 English Language Arts, Social Studies and Career EducationDocument13 pagesGrade 4/5: Week 19: Feb 8-11, 2020 English Language Arts, Social Studies and Career EducationKonhoNo ratings yet

- Migration Pattern and Urban Informal Sector of Bangladesh The Applicability of The Harris Todaro Migration Model in The Presence of COVID 19 OutbreakDocument11 pagesMigration Pattern and Urban Informal Sector of Bangladesh The Applicability of The Harris Todaro Migration Model in The Presence of COVID 19 OutbreakEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Habitat International: Md. Ashiq Ur Rahman, Astrid LeyDocument9 pagesHabitat International: Md. Ashiq Ur Rahman, Astrid LeyRisna Imanda RegarNo ratings yet

- Econ Dev - Part C.3Document2 pagesEcon Dev - Part C.3Darryl LabradorNo ratings yet

- Dhaka CP 2Document63 pagesDhaka CP 2mohanvelinNo ratings yet

- Migration and decent work. Challenges for the Global SouthFrom EverandMigration and decent work. Challenges for the Global SouthNo ratings yet

- Indian MillennialsDocument14 pagesIndian MillennialsS.Prabakaran S.PrabakaranNo ratings yet

- SR23826192214Document6 pagesSR23826192214Shilpa MuralidharNo ratings yet

- Slum Upgrading: by Nora Sticzay and Larissa Koch, Wageningen University and Research CentreDocument8 pagesSlum Upgrading: by Nora Sticzay and Larissa Koch, Wageningen University and Research CentreZeinab NadeemNo ratings yet

- Icssr Unicef PDFDocument248 pagesIcssr Unicef PDFAshashwatme100% (1)

- Groutsis, NG & Ozturk - IHRM - Chapter 2Document24 pagesGroutsis, NG & Ozturk - IHRM - Chapter 2Uly SsesNo ratings yet

- Limits2015 TomlinsonDocument3 pagesLimits2015 TomlinsonBauerPowerNo ratings yet

- Wage Rate and Local Migration Correlation: Addressing Rapid Urbanization in Metro Manila With Selected Cases of Households FromDocument9 pagesWage Rate and Local Migration Correlation: Addressing Rapid Urbanization in Metro Manila With Selected Cases of Households FromJoseph TalubanNo ratings yet

- Transportation Needs and Mobility Patterns of Persons ExperiencingDocument8 pagesTransportation Needs and Mobility Patterns of Persons ExperiencinggharehghashloomarjanNo ratings yet

- Habitat International: Seong Hun Yoo, Byungwon WooDocument9 pagesHabitat International: Seong Hun Yoo, Byungwon WooAhmed RagabNo ratings yet

- Migeration Rural and UrbanDocument11 pagesMigeration Rural and UrbanAjay_mane22No ratings yet

- Cities: Tatiana C.G. Trindade, Heather L. Maclean, I. Daniel PosenDocument15 pagesCities: Tatiana C.G. Trindade, Heather L. Maclean, I. Daniel PosenAhmed RagabNo ratings yet

- 04 CDP 2017 2020Document21 pages04 CDP 2017 2020Chesca LaurinNo ratings yet

- Beegle Et Al (2011)Document24 pagesBeegle Et Al (2011)Hope LessNo ratings yet

- Mega Cebu Lantawanarticle Jan 2017Document4 pagesMega Cebu Lantawanarticle Jan 2017kyNo ratings yet

- 01+597 99Z - Article+Text 1722 1 4 20230131Document15 pages01+597 99Z - Article+Text 1722 1 4 20230131Laiba AqilNo ratings yet

- A Model For Population Displacement and ResettlementDocument21 pagesA Model For Population Displacement and ResettlementNafiseh RowshanNo ratings yet

- Global MigrationDocument28 pagesGlobal MigrationAngely LudoviceNo ratings yet

- Navigating HR Dynamics in BangladeshDocument14 pagesNavigating HR Dynamics in BangladeshMohammed J. SarwarNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Changes in Standard of Living Among The Slum Resettlers in Perumbakkam, ChennaiDocument7 pagesA Study On The Changes in Standard of Living Among The Slum Resettlers in Perumbakkam, ChennaiInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Fp4-Inclusive Cities - Enhancing The Positive Impact of Urban Migration v261119Document6 pagesFp4-Inclusive Cities - Enhancing The Positive Impact of Urban Migration v261119mugwaziwendotageonelNo ratings yet

- Developing Kasita Homes in ChinaDocument18 pagesDeveloping Kasita Homes in Chinaapi-331830880No ratings yet

- India and BotswanaDocument6 pagesIndia and Botswanaapi-242215284100% (1)

- Admsci 14 00049Document24 pagesAdmsci 14 00049Tijira TabNo ratings yet

- Social Housing As Investment-The Case For Incremental HousingDocument30 pagesSocial Housing As Investment-The Case For Incremental HousingMadhav BoharaNo ratings yet

- kij4Document10 pageskij4waciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0898122100003400 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0898122100003400 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877050917327254 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S1877050917327254 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- kij5Document10 pageskij5waciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1474667017328033 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1474667017328033 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- Resehk Aplle JuiceDocument6 pagesResehk Aplle Juicewaciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0042698900002595 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0042698900002595 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1474667017331336 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1474667017331336 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1474667017341010 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S1474667017341010 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- SIPRIPP21Document64 pagesSIPRIPP21waciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0927776512003426 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0927776512003426 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- S On The Yield of AppDocument8 pagesS On The Yield of Appwaciy70505No ratings yet

- Paster Barkai Golan 2008 Mouldy Fruits and Vegetables As A Source of Mycotoxins Part 2Document12 pagesPaster Barkai Golan 2008 Mouldy Fruits and Vegetables As A Source of Mycotoxins Part 2waciy70505No ratings yet

- Walitt Et Al-2015-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument54 pagesWalitt Et Al-2015-Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviewswaciy70505No ratings yet

- Immigrant CredentialsDocument10 pagesImmigrant Credentialswaciy70505No ratings yet

- Canadian Experience Discourse and Anti-Racialism in A Post-Racial SocietyDocument21 pagesCanadian Experience Discourse and Anti-Racialism in A Post-Racial Societywaciy70505No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0163725899000480 MainDocument18 pages1 s2.0 S0163725899000480 Mainwaciy70505No ratings yet

- Ucalgary 2021 Marulanda DavidDocument167 pagesUcalgary 2021 Marulanda Davidwaciy70505No ratings yet

- Admin,+cws19n3 MojabDocument6 pagesAdmin,+cws19n3 Mojabwaciy70505No ratings yet

- Capital Mobilization of Skilled Migrants - A Relational Perspective - Al Ariss - 2011 - British Journal of Management - Wiley Online LibraryDocument51 pagesCapital Mobilization of Skilled Migrants - A Relational Perspective - Al Ariss - 2011 - British Journal of Management - Wiley Online Librarywaciy70505No ratings yet

- Labour Market Experiences of Recent DependeDocument115 pagesLabour Market Experiences of Recent Dependewaciy70505No ratings yet

- An Overview of Discourses of Skilled ImmDocument35 pagesAn Overview of Discourses of Skilled Immwaciy70505No ratings yet

- Settlement of Newcomers To Canada Fall 2010Document224 pagesSettlement of Newcomers To Canada Fall 2010waciy70505No ratings yet

- Immigrant Skills and Immigrant Outcomes Under A SeDocument61 pagesImmigrant Skills and Immigrant Outcomes Under A Sewaciy70505No ratings yet

- 381 FullDocument8 pages381 Fullwaciy70505No ratings yet

- Immigration Policy, National Origin, and Immigrant Skills: A Comparison of Canada and The United StatesDocument46 pagesImmigration Policy, National Origin, and Immigrant Skills: A Comparison of Canada and The United Stateswaciy70505No ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Students Course Perception and Their Approaches To Studying in Undergraduate Science Courses A Canadian ExperienceDocument21 pagesThe Relationship Between Students Course Perception and Their Approaches To Studying in Undergraduate Science Courses A Canadian Experiencewaciy70505No ratings yet

- Evaluación Inglés - Quinto - Cantidad 31Document3 pagesEvaluación Inglés - Quinto - Cantidad 31Javier VanegasNo ratings yet

- Siebel Release Notes / Known IssuesDocument99 pagesSiebel Release Notes / Known Issues谢义军No ratings yet

- Tour Report SanchitDocument38 pagesTour Report SanchitSTAR PRINTINGNo ratings yet

- KolamDocument5 pagesKolamMizta HariNo ratings yet

- Ascia Action Plan Anaphylaxis Epipen Personal 2014Document1 pageAscia Action Plan Anaphylaxis Epipen Personal 2014api-247849891No ratings yet

- Establishing An Effective PLCDocument26 pagesEstablishing An Effective PLCRM MenoriasNo ratings yet

- Telling The Whole Truth: Albert Memmi: January 2018Document5 pagesTelling The Whole Truth: Albert Memmi: January 2018Amira ChattiNo ratings yet

- Development of Noise Absorbing Composite Materials Using Agro Waste ProductsDocument6 pagesDevelopment of Noise Absorbing Composite Materials Using Agro Waste Productssanjanna bNo ratings yet

- APD General OrdersDocument789 pagesAPD General OrdersAnonymous Pb39klJNo ratings yet

- Flexible Instruction Delivery Plan (Fidp)Document2 pagesFlexible Instruction Delivery Plan (Fidp)Neil Patrick John AlosNo ratings yet

- Happy Birthday PaperDocument1 pageHappy Birthday PaperSahil LakhaniNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research - Feb13Document4 pagesQualitative Research - Feb13AkashNo ratings yet

- English. 2nd Edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents, 1990Document4 pagesEnglish. 2nd Edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents, 1990Ishaque MozumderNo ratings yet

- Use Properties of Exponents: For Your NotebookDocument7 pagesUse Properties of Exponents: For Your Notebook미나No ratings yet

- Payment Procedure: Important!Document3 pagesPayment Procedure: Important!Iqra AyeshaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Stone Mastic Asphalt Mix by The Bailey Method DesignDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Stone Mastic Asphalt Mix by The Bailey Method DesignLin ChouNo ratings yet

- Wagner Die Supply: Suppliesforthe SteelruledieindustryDocument19 pagesWagner Die Supply: Suppliesforthe SteelruledieindustrySOE RestaurantNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam Schedule-Summer 2022 Weekdays and WeekendDocument14 pagesMidterm Exam Schedule-Summer 2022 Weekdays and Weekendmansoor malikNo ratings yet

- Annexure 2 - Common Mistakes in Prison Design (UNOPS, 2016)Document3 pagesAnnexure 2 - Common Mistakes in Prison Design (UNOPS, 2016)Razi MahriNo ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of Simple As Possible Computer (SAP-1)Document52 pagesDesign and Implementation of Simple As Possible Computer (SAP-1)Muhammad Anas 484-FET/BSEE/F18No ratings yet

- Hempel - RECOMMENDED PAINTING SPECIFICATIONS and MaintenanceDocument304 pagesHempel - RECOMMENDED PAINTING SPECIFICATIONS and MaintenanceFachreza AkbarNo ratings yet

- Cuando Dios Escribe Tu Historia de Amor PDF DescargarDocument2 pagesCuando Dios Escribe Tu Historia de Amor PDF DescargarHernandez Ramirez Pepe0% (1)

- Au t2 S 1596 Southern Lights Powerpoint English Ver 1Document7 pagesAu t2 S 1596 Southern Lights Powerpoint English Ver 1IONELA-MARIA CRETANo ratings yet

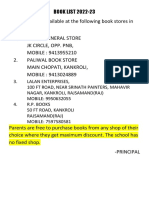

- Booklist 1Document19 pagesBooklist 1Suhana LaddhaNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Management and Commerce - South Eastern University of Sri LankaDocument28 pagesFaculty of Management and Commerce - South Eastern University of Sri LankaruzaikanfNo ratings yet