Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Paul Rudolph's Fluted Concrete Buildings - tcm45-344645

Uploaded by

Shuvro SarkarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Paul Rudolph's Fluted Concrete Buildings - tcm45-344645

Uploaded by

Shuvro SarkarCopyright:

Available Formats

Paul Rudolphs Fluted Concrete Buildings

S

ince 1962, architect Paul Rudolph of New Haven, Connecticut, has been developing a technique for building in concrete which demonstrates a new means for achieving a beautiful concrete finish. In the Yale University Art and A rc h i t e c t u re building in New Haven, and in the Endo Laboratories building at Garden City, Long Island, Mr. Rudolph has built with a rough concrete surface. Rather than showing the wood texture of the concrete forms after they have been removed, this surface shows the beauty of the concrete itself. Mr. Rudolphs method invo l ve s the preparation of finned forms. On a plywood backing, trapezoidal fins 2 inches deep by 1 _ inches at the base by _ inch at the top are nailed in place. They form a regular pattern, the space between the fins being equal to the width of the fins. These forms are placed as usual for any concrete wall. A stiff mixture of concrete with about a 2-inch slump and 1- to 1 1/2-inch aggregate is then placed. Cement, sand, and aggregate for the entire job are stock-piled before starting in order to assure consistency of surface tone. After removal of the forms, the fins are broken off with a hammer, thus exposing the aggregate. Often the aggregate breaks along with the concrete, and the interior tones of the aggregate are exposed. The stiff mixture avoids filming over aggregate stones which are not broken. In this way, the building takes on the warm tone of the aggregate. This method does more than decorate an otherwise smooth concrete surface. Often used both inside and outside, it eliminates the necessity of any further finishing of the conc re t e. In addition, the vertical fins suppress the subtle color changes visible in a smooth concrete surface. The finned method of concrete surface treatment was developed for the building at Yale, where Mr. Rudolph is chairman of the architectural department. Se ve ral experiments were made before the successful method was found. One experiment involved backing the t ra p ezoidal elements with cross slats, in order to achieve the rough surface without the necessity of hammering. This method, howe ve r, was found to produce too weak a form when applied to the scale necessary in building. Therefore, the plywood backing was used. A large sample section was placed on the building site before the method was approved. Nearly all concrete surfaces in the Yale building are treated with the rough finned technique. The four hollow rectangular pillars which are the major structural elements rising inside the building are finished in this way. Those walls which are not glass are also treated with fins. Only parts of the basements and the sixth and seventh floors, where artists need tackable surfaces, are given a smooth finish. The Long Island laboratory differs from the Yale Art and Architecture building in two ways. First, the finned technique, used only on flat surfaces in New Haven, is applied to curved surfaces. In most places this is done without the necessity of curving the forms. The transitions between 1-foot flat segments set on a curve are easily obscured by the activity of the fluted surface. The appearance is that of a true curve. A true curve was, in fact, used on the forms of only a small portion of the building. On the whole, the corduroy surface is used more sparingly at Endo. The only interiors finished with the rough surface are those of the turrets on the office wing and of the lobby. The remainder of the building called for smooth interior finish, since it is to be used for laboratories. General contractor for Yales Art and Architecture building was the George B. H. Macomber Company. The aggregate for the Yale building was brought from Easton, Massachusetts. The Easton stone was chosen for its warm yellow and gold tones which would be exposed by the hammering. The aggregate for the Endo building was a standard bank-run gra ve l from Long Island. This stone has a high percentage of light-colored quartz. All the concrete work on that building was done by the Ce n t ra l Cement Finishing Company of New York City. General contractors were Walter Kidde Constructors. Both jobs ran an average cost of $26.00 per square foot. The Rudolph treatment calls for one to two dollars more per square foot than a conventional concrete surface. This figure includes the extra one inch of width which must be allowed in the volume of concrete, and the cost of creating the fluted forms. The fluted technique, howe ve r, still underprices many alternative surface treatments, since the final surface is built into the concrete walls.

A chipper, one of four employed nearly full time on this aspect of the construction of the Yale building, executes the final step in creating the crusted concrete surface. Forms have just been removed from flutings at the left. Note that practically no pebbles are visible in the concrete. Photo shows a chipper breaking off the fluting with a hammer, exposing the aggregate. One piece of broken concrete flies off (in front of shadow).

A stack of the concrete forms (left) used to achieve the fluted, crusted surface of Yales Art and Architecture building. These fluted forms were cut and made in a shop on the building site. Endo Laboratories, Garden City, Long Island. Nearly all surfaces of this building are finished in the same crusted technique.

Sketch shows details of construction of forms for casting of the walls. Beveled fir strips were nailed on vertically and secured with walers and 1/2-inch bolts.

The Art and Architecture Building at Yale University was designed by architect Paul Rudolph and is built chiefly of reinforced concrete. The unusual fluted concrete finish is used on both interior and exterior surfaces.

PUBLICATION #C650084, Copyright 1965, The Aberdeen Group, All rights reserved

You might also like

- Components of A BuildingDocument9 pagesComponents of A BuildingNery Josue Villachica Hurtado100% (3)

- Chapter - 6 - BricksDocument56 pagesChapter - 6 - BricksPutry JazmeenNo ratings yet

- Visit Construction Site ReportDocument9 pagesVisit Construction Site Reportउमेश गावंडे100% (3)

- My Favorite HafizDocument57 pagesMy Favorite HafizIlaria MallardiNo ratings yet

- My Favorite HafizDocument57 pagesMy Favorite HafizIlaria MallardiNo ratings yet

- Top RCC Questions Asked in SSC JEDocument41 pagesTop RCC Questions Asked in SSC JEaman67% (9)

- 12 Samss 005 PDFDocument6 pages12 Samss 005 PDFfetihNo ratings yet

- Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum - tcm45-339863Document4 pagesFrank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum - tcm45-339863Paraskeui PapaNo ratings yet

- Walls: Presented By: Manoj Kader Vengatesh DeekshiDocument24 pagesWalls: Presented By: Manoj Kader Vengatesh DeekshiDEEKSHI MNo ratings yet

- Tech Drawing ProjectDocument30 pagesTech Drawing ProjectchukyzillaNo ratings yet

- Report of CTBMMSMT 1Document15 pagesReport of CTBMMSMT 1api-291031287No ratings yet

- Record 28 PDFDocument18 pagesRecord 28 PDFSakisNo ratings yet

- Construction of Foundation - Depth, Width, Layout and ExcavationDocument87 pagesConstruction of Foundation - Depth, Width, Layout and ExcavationGBABE ELIJAHNo ratings yet

- Structural Concept For ArchDocument15 pagesStructural Concept For ArchRonie SapadNo ratings yet

- Decorative Concrete - Growth and Creativity - tcm45-589925Document4 pagesDecorative Concrete - Growth and Creativity - tcm45-589925Fare NienteNo ratings yet

- Construction of Foundations - Excavation, Layout & DepthDocument9 pagesConstruction of Foundations - Excavation, Layout & DepthRajesh KhadkaNo ratings yet

- A New Method of Texturing Concrete Walls - tcm45-344375Document2 pagesA New Method of Texturing Concrete Walls - tcm45-344375cottchen6605No ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document61 pagesChapter 11yitayew tedilaNo ratings yet

- Tilt-Up Concrete House - Low Cost Luxury - tcm45-344462Document2 pagesTilt-Up Concrete House - Low Cost Luxury - tcm45-344462mrelfeNo ratings yet

- Obembe Olayemi EmmanuelDocument5 pagesObembe Olayemi EmmanuelOlayemi ObembeNo ratings yet

- Foundation Failure Residential Building in The Southern Part of Tel AvivDocument12 pagesFoundation Failure Residential Building in The Southern Part of Tel AvivloloNo ratings yet

- Building construction steps and materialsDocument17 pagesBuilding construction steps and materialsAbhishek MeenaNo ratings yet

- Site Visit ReportDocument5 pagesSite Visit ReportAbubakar Abdul RaufNo ratings yet

- Concrete Construction Article PDF - National Gallery Exhibits The Cutting Edge of Contemporary Architectural ConcreteDocument4 pagesConcrete Construction Article PDF - National Gallery Exhibits The Cutting Edge of Contemporary Architectural ConcreteDhruvi KananiNo ratings yet

- 2005 Chapter SIDBuildingÅrhusDocument6 pages2005 Chapter SIDBuildingÅrhusKarolina BiegałaNo ratings yet

- John Rhey L. Tagalog BD 1 - Activity 5Document5 pagesJohn Rhey L. Tagalog BD 1 - Activity 5John Rhey Lofranco TagalogNo ratings yet

- I.M. Pei's Groundbreaking ArchitectureDocument73 pagesI.M. Pei's Groundbreaking ArchitecturePrakhar JainNo ratings yet

- Construction of HouseDocument14 pagesConstruction of HouseKush Gondaliya100% (1)

- Joint Free Slabs On Grade An Innovative Approach WorkingDocument6 pagesJoint Free Slabs On Grade An Innovative Approach Workingmehdi_hoseineeNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Strength of Block Made From Cement and Lateritic SoilDocument10 pagesComparison of The Strength of Block Made From Cement and Lateritic SoilStephen Hardeykunle OladapoNo ratings yet

- Stone/CHB/Cement: RE200 - AR161Document36 pagesStone/CHB/Cement: RE200 - AR161magne veruNo ratings yet

- Background English BondDocument9 pagesBackground English BondasdqwerNo ratings yet

- Building Materials For ConstructionDocument52 pagesBuilding Materials For ConstructionLaxmana PrasadNo ratings yet

- Sequence of Work in Building ConstructionDocument8 pagesSequence of Work in Building ConstructionPurushottam PoojariNo ratings yet

- CBD222 NATURALLY QUARRIED STONES VS ARTIFICIAL STONESDocument8 pagesCBD222 NATURALLY QUARRIED STONES VS ARTIFICIAL STONESBoiki RabewuNo ratings yet

- Sun City, AZ - 1964 - "Research House"Document84 pagesSun City, AZ - 1964 - "Research House"Del Webb Sun Cities MuseumNo ratings yet

- Paolo Fabugais Dain Casalta Chelsa Tapis: Construction Materials A. ConcreteDocument9 pagesPaolo Fabugais Dain Casalta Chelsa Tapis: Construction Materials A. ConcretePaolo Miguel FabugaisNo ratings yet

- Report BataDocument17 pagesReport BataLutadias InawafaysNo ratings yet

- English BondDocument7 pagesEnglish BondJEN YEE LONGNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 BricksDocument56 pagesChapter 6 BricksDdeqz Elina Bueno I100% (1)

- Sydney Opera House: Subject-Advanced Structural SystemsDocument15 pagesSydney Opera House: Subject-Advanced Structural Systemspriyanka100% (1)

- MANUFACTURING OF BRICKS ReportDocument30 pagesMANUFACTURING OF BRICKS ReportRajat Mangal100% (2)

- Eames House Conservation Project PDFDocument3 pagesEames House Conservation Project PDFAna Paula Ribeiro de AraujoNo ratings yet

- MCM Assignment 1Document5 pagesMCM Assignment 1arnabgogoiNo ratings yet

- Assignment in CE513 Building ConstructionDocument7 pagesAssignment in CE513 Building ConstructionFrancis Prince ArtiagaNo ratings yet

- Construction Technology BrickworkDocument23 pagesConstruction Technology BrickworkdahliagingerNo ratings yet

- BM 5-ConcreteDocument81 pagesBM 5-ConcreteArch Reem AlzyoudNo ratings yet

- Brick MasonryDocument48 pagesBrick MasonryKannan Gnanaprakasam100% (1)

- Basic Components of A BuildingDocument13 pagesBasic Components of A Buildingkhim zukami100% (1)

- Faculty of Aechitecture and Planning, Aktu, Lucknow: SESSION-2020-21Document17 pagesFaculty of Aechitecture and Planning, Aktu, Lucknow: SESSION-2020-21Vikash KumarNo ratings yet

- How to Design and Build Poured Concrete Retaining WallsDocument5 pagesHow to Design and Build Poured Concrete Retaining WallsHardik SarvaiyaNo ratings yet

- Housing Module 4Document11 pagesHousing Module 4Kyla TiangcoNo ratings yet

- Building A Concrete Spiral StairwayDocument5 pagesBuilding A Concrete Spiral StairwaywalaywanNo ratings yet

- Tugas BHS InggrisDocument32 pagesTugas BHS InggrischrisnaNo ratings yet

- CT ReportDocument5 pagesCT ReportKAR WEI LEENo ratings yet

- Texture and Light in ArchitectureDocument18 pagesTexture and Light in ArchitectureSamantha BaldovinoNo ratings yet

- Brick MasonaryDocument42 pagesBrick MasonarySaddam HossainNo ratings yet

- Practica5 en InglesDocument7 pagesPractica5 en InglesStephan SantosNo ratings yet

- Brick MasonryDocument12 pagesBrick MasonrySanjaya PoudelNo ratings yet

- Refurbishment of IT Theme Centre with Polymer ConcreteDocument18 pagesRefurbishment of IT Theme Centre with Polymer ConcretenamrataNo ratings yet

- Lect +03 +the+Principles+of+CompositionDocument147 pagesLect +03 +the+Principles+of+CompositionJoy ShiNo ratings yet

- Tama Art University LibraryDocument61 pagesTama Art University LibrarySiulca Andreina Luna Salazar100% (3)

- Cracking of RC School Building Due To Soil Expansion: Omer S. Mughieda and Khaldoon A. Bani-HaniDocument16 pagesCracking of RC School Building Due To Soil Expansion: Omer S. Mughieda and Khaldoon A. Bani-HaniEng mohammadNo ratings yet

- Khulna Report Final Print 06-01-17Document33 pagesKhulna Report Final Print 06-01-17Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Reference:: MGT 511 - QBANK - 30MAR2017Document20 pagesReference:: MGT 511 - QBANK - 30MAR2017Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Reference:: MGT 511 - QBANK - 30MAR2017Document20 pagesReference:: MGT 511 - QBANK - 30MAR2017Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Technology Parks Services On The High Technology Industry: A Case Study On Kulim Hi-Tech ParkDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Technology Parks Services On The High Technology Industry: A Case Study On Kulim Hi-Tech ParkShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Cpw-Fed Antennas For Wifi and Wimax: January 2012Document31 pagesCpw-Fed Antennas For Wifi and Wimax: January 2012Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- 1 ZJ - KB Ïiæ N "Q Cövmövwgs-Gi NV Zlwo: Wugmwe WDocument3 pages1 ZJ - KB Ïiæ N "Q Cövmövwgs-Gi NV Zlwo: Wugmwe WShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Installation Guide R19 USDocument25 pagesInstallation Guide R19 USLori LoriNo ratings yet

- BudgetDocument1 pageBudgetShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- 4 Years in JourneyDocument13 pages4 Years in JourneyShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Meridian Park Design GuidelinesDocument68 pagesMeridian Park Design GuidelinesSidra JaveedNo ratings yet

- 1 ZJ - KB Ïiæ N "Q Cövmövwgs-Gi NV Zlwo: Wugmwe WDocument3 pages1 ZJ - KB Ïiæ N "Q Cövmövwgs-Gi NV Zlwo: Wugmwe WShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Basic Plumbing SystemDocument48 pagesBasic Plumbing SystemShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Distribution System PDFDocument19 pagesDistribution System PDFShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Distribution SystemDocument19 pagesDistribution SystemShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- ARC 331 17 - Vision For The CityDocument69 pagesARC 331 17 - Vision For The CityShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- ARC 441 - Specification - Reading Material Part 01Document8 pagesARC 441 - Specification - Reading Material Part 01Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- The Planning and Design of Science and T PDFDocument209 pagesThe Planning and Design of Science and T PDFShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- EPZ Building Code PDFDocument9 pagesEPZ Building Code PDFShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- ARC 441 - Specification - Reading Material Part 01Document8 pagesARC 441 - Specification - Reading Material Part 01Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Power of Public PlazasDocument17 pagesPower of Public PlazasShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Animation enDocument2 pagesBachelor of Animation enShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Plummy FashionsDocument23 pagesPlummy FashionsShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Four Steps To Pure Iman - Explanations of A Painting by M. R. Bawa MuhaiyaddeenDocument79 pagesFour Steps To Pure Iman - Explanations of A Painting by M. R. Bawa MuhaiyaddeenPakistani99100% (1)

- Bachelor of Animation enDocument2 pagesBachelor of Animation enShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Paul Rudolph's Fluted Concrete Buildings - tcm45-344645Document2 pagesPaul Rudolph's Fluted Concrete Buildings - tcm45-344645Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- DEV Suggestions!Document1 pageDEV Suggestions!Shuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Welcome: Economical Progress of Bangladesh Over The DecadesDocument10 pagesWelcome: Economical Progress of Bangladesh Over The DecadesShuvro SarkarNo ratings yet

- Chap 1 Intro To Systems Analysis and Design 2Document50 pagesChap 1 Intro To Systems Analysis and Design 2Hai MenNo ratings yet

- Time Table Even Sem 18-19 (II, III and IV - PT) To WebsiteDocument42 pagesTime Table Even Sem 18-19 (II, III and IV - PT) To WebsiteAnonymous n7zsf8w7aNo ratings yet

- LECTURE 1 Kinematics Fundamentals PDFDocument79 pagesLECTURE 1 Kinematics Fundamentals PDFNik ZulhilmiNo ratings yet

- Ufc 3-310-04Document16 pagesUfc 3-310-04sherylz0% (1)

- Introduction To Systems Engineering Practices:: Session I - RequirementsDocument52 pagesIntroduction To Systems Engineering Practices:: Session I - RequirementssuksesbesarNo ratings yet

- AS 3735 - Concrete Structures For Retaining LiquidsDocument27 pagesAS 3735 - Concrete Structures For Retaining LiquidslowiyaunNo ratings yet

- Syed Sohail Hamid Zaidi: A: Technical Aspects and Areas of ExpertiseDocument13 pagesSyed Sohail Hamid Zaidi: A: Technical Aspects and Areas of ExpertiseAfrasyab KhanNo ratings yet

- Embedded Systems: Objectives: After Reading This Chapter, The Reader Should Be Able To Do The FollowingDocument11 pagesEmbedded Systems: Objectives: After Reading This Chapter, The Reader Should Be Able To Do The Followingwalidghoneim1970No ratings yet

- St. Peter's College BSCE Curriculum 2020-2021Document1 pageSt. Peter's College BSCE Curriculum 2020-2021Arafat BauntoNo ratings yet

- Software Engineering MCQDocument63 pagesSoftware Engineering MCQPratyushNo ratings yet

- CMP E2FW Flameproof ATEX Cable Glands For Lead Sheathed CablesDocument1 pageCMP E2FW Flameproof ATEX Cable Glands For Lead Sheathed CablesrocketvtNo ratings yet

- Culvert 1x2x2 0.50 CushionDocument22 pagesCulvert 1x2x2 0.50 CushionubiakashNo ratings yet

- Column Design - Staad ReactionsDocument12 pagesColumn Design - Staad ReactionsNitesh SinghNo ratings yet

- 15SE202 SoftwareEP SyllabusDocument2 pages15SE202 SoftwareEP SyllabusAnonymous k1cZPS5xX0% (1)

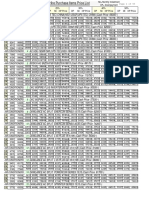

- PriceListHirePurchase Normal 1Document55 pagesPriceListHirePurchase Normal 1Muhammad HajiNo ratings yet

- Power System Design Basics Tb08104003e PDFDocument145 pagesPower System Design Basics Tb08104003e PDFRochelle Ciudad BaylonNo ratings yet

- Silangan Fit OutDocument5 pagesSilangan Fit OutNova CastyNo ratings yet

- CoursesDocument1 pageCoursesNorthTempleNo ratings yet

- Design of Concrete Structure II Sessional: Dhaka University of Engineering & TechnologyDocument22 pagesDesign of Concrete Structure II Sessional: Dhaka University of Engineering & TechnologyumrumrumrNo ratings yet

- Research Scientist - Engineer Job - Ingenia Polymers - Brantford, ON - Indeed - CaDocument2 pagesResearch Scientist - Engineer Job - Ingenia Polymers - Brantford, ON - Indeed - Caming_zhu10No ratings yet

- LS - Susol Series PDFDocument354 pagesLS - Susol Series PDFThinh TranNo ratings yet

- MECHCON A Corporate ProfileDocument40 pagesMECHCON A Corporate ProfileMuhammad AzeemNo ratings yet

- Elements of Masonry DesignDocument83 pagesElements of Masonry DesigndyetNo ratings yet

- EGD Lab ManualDocument15 pagesEGD Lab ManualRajesh ANo ratings yet

- Research HighlightDocument209 pagesResearch HighlightMuhammad Noor KholidNo ratings yet

- P 192.481 Visually Inspect For Atmospheric Corrosion RevisionsDocument2 pagesP 192.481 Visually Inspect For Atmospheric Corrosion RevisionsahmadlieNo ratings yet

- Space RoboticsDocument9 pagesSpace RoboticsRushikesh WareNo ratings yet