Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Individual Moral Development

Individual Moral Development

Uploaded by

Francis NicorOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Individual Moral Development

Individual Moral Development

Uploaded by

Francis NicorCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction

At first glance, one of the most obvious places to look for moral progress is in individuals, in

particular in moral development from childhood to adulthood. In fact, that moral progress is

possible is a foundational assumption of moral education. Parents and teachers would not teach

children that they should not hurt their pet, be kind to their siblings or explain why they should

not cheat at an exam if they did not believe that this would contribute to the moral improvement

of children. Beyond the general agreement that moral progress is not only possible but even a

common feature of human development things become blurry, however. For what do we mean

by ‘progress’? And what constitutes moral progress? Does the idea of individual moral progress

presuppose a predetermined end or goal of moral education and development, or not? Is the kind

of progress we might make as adults of the same kind as that we might make in our growth to

adulthood, or is a different notion of progress at play here? In this paper we approach these

questions through analyses of, firstly, the concept of moral progress (Section 2) and secondly,

the psychology of moral development (Section 3). Thus, we use the literature on the concept of

moral progress to shed light on the psychology of moral development and vice versa; and we will

see that both analyses mutually support each other. Section 4 will be devoted to a comparison of

the moral progress of children and that of adults. We will end with a summary of our findings

and some concluding remarks.

The Concept of Moral Progress

To clarify the notion of moral progress we will distinguish (1) a strong and a weak concept, (2)

different levels on which progress may take place, and (3) formal and substantial criteria of

moral progress.

The Weak and the Strong Concept of Progress

The core of the concept of progress is ‘things getting better’. But is there more to it than that? In

everyday life we often speak of progress when things at a certain time are better than they were

at a previous time. For instance, a parent may look at a child’s school report, notice that on

average the child has received higher grades and say that the child has made progress. In the

literature the concept of progress is sometimes explained this way, as simply a combination of a

descriptive element (the observed change) and a normative or evaluative element (the evaluation

of the observed change) (Macklin 1977: 372–373). More often, however, a further element is

added to the concept of progress. Perhaps the child was lucky to get better grades; the exam

questions just happened to fall right. To be able to speak of progress it seems we need to know

more about the background of the change, and have reason to think the observed ‘trend’ will

consolidate itself, will indeed be a trend.

You might also like

- Addicted To Adultery - Douglas WeissDocument63 pagesAddicted To Adultery - Douglas WeissDavid chinonso100% (2)

- Human-DevelopmentDocument14 pagesHuman-DevelopmentJewel SkyNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent DevelopmentDocument288 pagesChild and Adolescent DevelopmentHann alvarezNo ratings yet

- Module in ED101 Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning Principles PDFDocument61 pagesModule in ED101 Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning Principles PDFAnjela April93% (100)

- Chapter 1 - Ethics and BusinessDocument14 pagesChapter 1 - Ethics and BusinessAbhishek Kumar Sahay100% (1)

- Module 2 - The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesDocument4 pagesModule 2 - The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesMarkhill Veran Tiosan100% (2)

- Can Business Ethics Be TaughtDocument20 pagesCan Business Ethics Be TaughtDarwin Dionisio ClementeNo ratings yet

- Funda - NursingDocument29 pagesFunda - NursingLloyd Rafael EstabilloNo ratings yet

- Theories of Human DevelopmentDocument8 pagesTheories of Human DevelopmentJessel Mae Dacuno100% (1)

- Prof Ed Exam - 900 Items (Makatulog Kapa Sana Hahaha)Document94 pagesProf Ed Exam - 900 Items (Makatulog Kapa Sana Hahaha)Shenna LimNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Social Responsibility and Ethics in Strategic ManagementDocument15 pagesChapter 3 - Social Responsibility and Ethics in Strategic ManagementMohammod TahmidNo ratings yet

- Child & Adolescent DevelopmentDocument34 pagesChild & Adolescent DevelopmentJustine Marquizo SanoriaNo ratings yet

- FC Practice Test 3 80 PPDocument82 pagesFC Practice Test 3 80 PPJoshua B. JimenezNo ratings yet

- Professional EthicsDocument21 pagesProfessional EthicsDr. Yashpreet Kaur100% (1)

- Childhood and Growing UpDocument72 pagesChildhood and Growing UpDurgesh100% (3)

- Educ. - 1-A Rudy 22Document26 pagesEduc. - 1-A Rudy 22Mary Rose Ponte Fernandez89% (38)

- Velasquez Business Ethics - Short VersionDocument69 pagesVelasquez Business Ethics - Short VersionIndraNo ratings yet

- Personal Development - Module 2Document12 pagesPersonal Development - Module 2joemariekeytNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Developmental PsychologyDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Developmental PsychologyTimothy JamesNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two Human Development Chapter Overview: Brainstorming QuestionsDocument12 pagesChapter Two Human Development Chapter Overview: Brainstorming QuestionsDawitNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document13 pagesUnit 1rajNo ratings yet

- Cad Week 1Document3 pagesCad Week 1Alyssa Crizel CalotesNo ratings yet

- Lesson No. 2Document15 pagesLesson No. 2Hezel CabunilasNo ratings yet

- Professional Education 101: in This Module, We Will Learn About "The Child and AdolescentDocument9 pagesProfessional Education 101: in This Module, We Will Learn About "The Child and AdolescentFloyd LawtonNo ratings yet

- Module 1 The Child and Adolescent Learner and Learning PrinciplesDocument8 pagesModule 1 The Child and Adolescent Learner and Learning PrinciplesBernard OnasinNo ratings yet

- FTC 1 Unit 1Document9 pagesFTC 1 Unit 1Lady lin BandalNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Health, Growth and DevelopmentDocument12 pagesChild and Adolescent Health, Growth and DevelopmentBackpackerJean ReyesLacanilaoNo ratings yet

- Number Content 1. Table of Content 1 2. Acknowledgement 2 3. 3 4. 4-5Document32 pagesNumber Content 1. Table of Content 1 2. Acknowledgement 2 3. 3 4. 4-5Shamsul Izwan RosliNo ratings yet

- ED1 AssignmentDocument4 pagesED1 AssignmentHazel De La VegaNo ratings yet

- Growth and Development KozierDocument41 pagesGrowth and Development KozierGeguirra, Michiko SarahNo ratings yet

- Functions of Applied Social Science, TomeDocument16 pagesFunctions of Applied Social Science, TomeKyla KateNo ratings yet

- Assignment No. 1: - Provide An Overview of Growth and DevelopmentDocument21 pagesAssignment No. 1: - Provide An Overview of Growth and DevelopmentQaiser KhanNo ratings yet

- Growth Vs DevelopmentDocument21 pagesGrowth Vs Developmentusman razaNo ratings yet

- Psychology and EducationDocument4 pagesPsychology and Educationapril marieNo ratings yet

- Jered Morato BTLED-3 Child and Adolescent Development - Lesson 2Document4 pagesJered Morato BTLED-3 Child and Adolescent Development - Lesson 2Jered MoratoNo ratings yet

- 8610 Assignment AiouDocument22 pages8610 Assignment AiouNoor Ul AinNo ratings yet

- Assignment No. 1 Sidra SaleemDocument16 pagesAssignment No. 1 Sidra SaleemAmmar IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Prof. Ed 1 ModulesDocument144 pagesProf. Ed 1 ModulesSheyne CauanNo ratings yet

- Growth and DevelopmentDocument38 pagesGrowth and DevelopmentKristle Tumaliuan CatindoyNo ratings yet

- Module 3-Meaning of TermsDocument19 pagesModule 3-Meaning of TermsKimberly VergaraNo ratings yet

- AdolescentDocument12 pagesAdolescentHeveanah Alvie Jane BalabaNo ratings yet

- Unit-5 060607Document4 pagesUnit-5 060607John Mark AlagonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document9 pagesChapter 1Jane Clair Servancia MarfilNo ratings yet

- IC103 - General Psychology: Psychology of Human Growth and DevelopmentDocument15 pagesIC103 - General Psychology: Psychology of Human Growth and DevelopmentKimberly PeolioNo ratings yet

- Human Development Ncert QuestionsDocument6 pagesHuman Development Ncert QuestionsYuvana SinghNo ratings yet

- Assignment No. 1 FazilaDocument16 pagesAssignment No. 1 FazilaAmmar IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document9 pagesModule 1Marls PantinNo ratings yet

- 002 Exam Guide Dec 21 SampleDocument18 pages002 Exam Guide Dec 21 SampleCSENo ratings yet

- Development and GrowthDocument4 pagesDevelopment and GrowthRaia EscameNo ratings yet

- Part 1Document1 pagePart 1Heart WpNo ratings yet

- EbookDocument9 pagesEbookod armyNo ratings yet

- Human Development: Meaning, Concepts and ApproachesDocument8 pagesHuman Development: Meaning, Concepts and ApproachesAsida Maronsing DelionNo ratings yet

- The Child and Adolescent Learner and Learning Principles: Ms. Grace Pangilinan Gulapa, LPT InstructorDocument37 pagesThe Child and Adolescent Learner and Learning Principles: Ms. Grace Pangilinan Gulapa, LPT InstructorTeddy Tumanguil TesoroNo ratings yet

- Module (Profed)Document6 pagesModule (Profed)JC SanchezNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document23 pagesModule 1Bulan BulawanNo ratings yet

- EbookDocument10 pagesEbookod armyNo ratings yet

- Developmental TheoriesDocument7 pagesDevelopmental TheoriesAngel YadisNo ratings yet

- ProfEd1 Module 1Document6 pagesProfEd1 Module 1Melchor Baniaga100% (1)

- Human Development - 0Document5 pagesHuman Development - 0Reafe LanzaderasNo ratings yet

- TC 001 - Module 3 Issues On Human Development Tasks GCDocument7 pagesTC 001 - Module 3 Issues On Human Development Tasks GCFelicity Joy VLOGSNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Human Development, Meaning, Concepts and Approaches Content OutlineDocument28 pagesModule 1: Human Development, Meaning, Concepts and Approaches Content OutlineCristine Joy CalingacionNo ratings yet

- Shannen Kaye Educ 1Document9 pagesShannen Kaye Educ 1Sedsed QuematonNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Theoretical Perspectives of Development: StructureDocument11 pagesUnit 1 Theoretical Perspectives of Development: StructureTanyaNo ratings yet

- Term Paper - Human Growth Learning and DevelopmentDocument19 pagesTerm Paper - Human Growth Learning and Developmentbernadeth felizarteNo ratings yet

- CALLP - Chapter 1 (Studying Learners' Development)Document23 pagesCALLP - Chapter 1 (Studying Learners' Development)Jbp PrintshopNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Dev PsychDocument25 pagesChapter 1 - Dev Psychkyle lumugdangNo ratings yet

- Assignment Solution 8610Document16 pagesAssignment Solution 8610Haroon Karim BalochNo ratings yet

- IMRAD Format ResearchDocument4 pagesIMRAD Format ResearchCess MB ValdezNo ratings yet

- Child Adolescent ReflectionDocument5 pagesChild Adolescent ReflectionFlorencio CoquillaNo ratings yet

- Soil Erosion: Get The Huge List of More Than 500 Essay Topics and IdeasDocument1 pageSoil Erosion: Get The Huge List of More Than 500 Essay Topics and IdeasFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- Pampanga: Imparayan Elementary School Music 6 1 Summative Test - 3 QuarterDocument2 pagesPampanga: Imparayan Elementary School Music 6 1 Summative Test - 3 QuarterFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- Mind Mapping: A Prelude To Paragraph DevelopmentDocument15 pagesMind Mapping: A Prelude To Paragraph DevelopmentFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- Report On Attendance: No. of School Days No. of Days Present No. of Days AbsentDocument5 pagesReport On Attendance: No. of School Days No. of Days Present No. of Days AbsentFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- Tesda Region VIDocument3 pagesTesda Region VIFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- REPUBLIC ACT NO 10647 Sec 1-3Document2 pagesREPUBLIC ACT NO 10647 Sec 1-3Francis NicorNo ratings yet

- Improving The Quality of Technical and Vocational Education in Slovakia For European Labour Market NeedsDocument9 pagesImproving The Quality of Technical and Vocational Education in Slovakia For European Labour Market NeedsFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- RA NO. 10647 Sec 4-6Document1 pageRA NO. 10647 Sec 4-6Francis NicorNo ratings yet

- Smea Report: 1st Quarter (January-March 2021)Document14 pagesSmea Report: 1st Quarter (January-March 2021)Francis NicorNo ratings yet

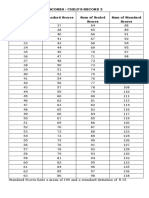

- Table 7. Interpretation of Standard Score or Development IndexDocument1 pageTable 7. Interpretation of Standard Score or Development IndexFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- SPEECH Believe in Yourself 2Document1 pageSPEECH Believe in Yourself 2Francis NicorNo ratings yet

- Omnibus Certification and Autheticity and Veracity of DocumentsDocument1 pageOmnibus Certification and Autheticity and Veracity of DocumentsFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- Scaled Score Equivalents of Raw Scores Age Band 5.1 - 5.11 YearsDocument1 pageScaled Score Equivalents of Raw Scores Age Band 5.1 - 5.11 YearsFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- Table of Standard Scores Child's Record 2Document1 pageTable of Standard Scores Child's Record 2Francis Nicor100% (4)

- Risk and Challenges in SchoolDocument4 pagesRisk and Challenges in SchoolFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- Technology and EducationDocument2 pagesTechnology and EducationFrancis NicorNo ratings yet

- The Moral Agent: Developing Virtue As HabitDocument12 pagesThe Moral Agent: Developing Virtue As HabitJeanette Torralba EspositoNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed 2 Module 1 1Document19 pagesProf Ed 2 Module 1 1PUNAY, PAMELA JANE, D.R.No ratings yet

- LAS Child & Adolescent 4Document5 pagesLAS Child & Adolescent 4Khiem RagoNo ratings yet

- Social Responsibility and Managerial Ethics: Stephen P. Robbins Mary CoulterDocument39 pagesSocial Responsibility and Managerial Ethics: Stephen P. Robbins Mary CoulterAbdul HannanNo ratings yet

- Ethics ReviewerDocument8 pagesEthics ReviewerMarie Pearl NarioNo ratings yet

- Soc Sci 101N Module 2Document4 pagesSoc Sci 101N Module 2Jane PadillaNo ratings yet

- Course-Module - Educ 1 Week 16Document19 pagesCourse-Module - Educ 1 Week 16DarcknyPusodNo ratings yet

- Full Download Ethics in Accounting A Decision Making Approach 1st Edition Solutions Klein PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Ethics in Accounting A Decision Making Approach 1st Edition Solutions Klein PDF Full Chapterapolloniccondylemoieax100% (14)

- Psychology Final Project PDFDocument12 pagesPsychology Final Project PDFapi-447026013No ratings yet

- DEMO TeachingDocument38 pagesDEMO TeachingJeh MatibagNo ratings yet

- Wagner & Rush (2000) - Altruistic OCBDocument14 pagesWagner & Rush (2000) - Altruistic OCBEmilia MiuNo ratings yet

- Unit 2: The Moral Agent: Topic 1: Culture and Its Roles in Moral BehaviorDocument21 pagesUnit 2: The Moral Agent: Topic 1: Culture and Its Roles in Moral BehaviorJohn Carlo LadieroNo ratings yet

- Qian Zhang & Honghui Zhao An Analyticak Overview O...Document10 pagesQian Zhang & Honghui Zhao An Analyticak Overview O...uki arrownaraNo ratings yet

- Kuther - Lifespan - Cog-Bio Dev. Early ChildhoodDocument76 pagesKuther - Lifespan - Cog-Bio Dev. Early ChildhoodLauren McCutcheonNo ratings yet

- LESSON 2 Pdev Part 5Document12 pagesLESSON 2 Pdev Part 5Mylen Noel Elgincolin ManlapazNo ratings yet

- Movie Review PaperDocument15 pagesMovie Review PaperWillie GoreNo ratings yet

- Educ 211 W7 11Document47 pagesEduc 211 W7 11Eugene BaronaNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics: Fon Univerzitet Prv-Privaten-Univerzitet-Vo-R.M. Fakultet Za Primeneti Stranski Jazici I BiznisDocument15 pagesBusiness Ethics: Fon Univerzitet Prv-Privaten-Univerzitet-Vo-R.M. Fakultet Za Primeneti Stranski Jazici I BiznisTrajko GjorgjievskiNo ratings yet

- The Social Norms of Tax ComplianceDocument19 pagesThe Social Norms of Tax Compliancewahyu artikaNo ratings yet

- Fostering Goodness & CaringDocument13 pagesFostering Goodness & CaringasmawiNo ratings yet