Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Insect Morphogenesis

Uploaded by

Akash DashOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Insect Morphogenesis

Uploaded by

Akash DashCopyright:

Available Formats

MORPHOGENESIS

Morphogenesis:

Once an insect hatches from the egg it is usually able to survive on its own, but it is small, wingless, and

sexually immature. Its primary role in life is to eat and grow. If it survives, it will periodically outgrow

and replace its exoskeleton (a process known as molting). In many species, there are other physical

changes that also occur as the insect gets older (growth of wings and development of external genitalia,

for example). Collectively, all changes that involve growth, molting, and maturation are known as

morphogenesis.

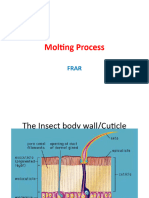

Moulting:

-The periodic process of loosening and discarding the cuticle, accompanied by the formation of a new

cuticula and often by structural changes in the body wall and other organs.

-Molting is a physiological phenomenon in which separation of old exoskeleton and replacing of new

cuticle is formed.

-Separation or shredding of old exoskeleton is known as molting.

-Molting The formation of new cuticle followed by ecdysis.

The molting process is triggered by hormones released when an insect's growth reaches the physical

limits of its exoskeleton. Each molt represents the end of one growth stage (instar) and the beginning

of another. In some insect species the number of instars is constant (typically from 3 to 15), but in

others it may vary in response to temperature, food availability, or other environmental factors. Molting

stops when the insect becomes an adult; energy for growth is then channeled into production of

eggs and sperm.

An insect cannot survive without the support and protection of its exoskeleton, so a new, larger

replacement must be constructed inside the old one. The molting process begins when epidermal

cells respond to hormonal changes by increasing their rate of protein synthesis. This quickly leads to

apolysis-physical separation of the epidermis from the old endocuticle. Epidermal cells fill the resulting

gap with an inactive molting fluid and then secrete a special lipoprotein (the cuticulin layer) that

insulates and protects them from the molting fluid's digestive action. This cuticulin layer becomes part of

the new exoskeleton's epicuticle.

After formation of the cuticulin layer, molting fluid becomes activated and chemically "digests" the

endocuticle of the old exoskeleton. Break-down products (amino acids and chitin microfibrils) pass

through the cuticulin layer where they are recycled by the epidermal cells and secreted under the

cuticulin layer as new procuticle (soft and wrinkled). Pore canals within the procuticle allow movement

of lipids and proteins toward the new epicuticle where wax and cement layers form.

When the new exoskeleton is ready, muscular contractions and intake of air cause the insect's body to

swell until the old exoskeleton splits open along lines of weakness (ecdysial sutures). The insect sheds

its old exoskeleton (ecdysis) and continues to fully expand the new one. Over the next few hours,

sclerites will harden and darken as quinone cross-linkages form within the exocuticle. This process

(called sclerotization or tanning) gives the exoskeleton its final texture and appearance.

An insect that is actively constructing new exoskeleton is said to be in a pharate condition. During the

days or weeks of this process there may be very little evidence of change. Ecdysis, however, occurs

quickly (in minutes to hours). A newly molted insect is soft and largely unpigmented (white or ivory). It

is said to be in a teneral condition until the process of tanning is completed (usually a day or two).

You might also like

- Hair and Hair Care PDFDocument681 pagesHair and Hair Care PDFpsychposters100% (1)

- The Biology of ScorpionsDocument233 pagesThe Biology of ScorpionsAymer VásquezNo ratings yet

- Acarology PDFDocument812 pagesAcarology PDFFrederico Kirst86% (29)

- Veterinary Embryology (Class Notes) PDFDocument77 pagesVeterinary Embryology (Class Notes) PDFluis feo0% (3)

- Arun PPT - PPTX ..HUMAN REPRODUCTION FOR HSC Board Maharashtra State..Document65 pagesArun PPT - PPTX ..HUMAN REPRODUCTION FOR HSC Board Maharashtra State..arunmishra1986100% (1)

- The Arthropods: Blueprint For SuccessDocument68 pagesThe Arthropods: Blueprint For SuccessKlym CaballasNo ratings yet

- Morphogenesis (From The Greek Morphê Shape and Genesis Meaning Beginning', LiterallyDocument11 pagesMorphogenesis (From The Greek Morphê Shape and Genesis Meaning Beginning', LiterallySundayNo ratings yet

- CP 3204 Assign FINALDocument7 pagesCP 3204 Assign FINALPrincess CabardoNo ratings yet

- ENT216 - Lecture 5 Integument MoultingDocument33 pagesENT216 - Lecture 5 Integument MoultingkaraboletheNo ratings yet

- 2molting ProcessDocument22 pages2molting ProcessGretz AnticamaraNo ratings yet

- Insect PhysiologyDocument34 pagesInsect PhysiologyVina MolinaNo ratings yet

- MoultingDocument12 pagesMoultingPushpinderNo ratings yet

- CuticleDocument7 pagesCuticleMuhammad SibtainNo ratings yet

- Animal Development 2Document7 pagesAnimal Development 2dewiNo ratings yet

- Bio 152 Lab 10 Animal Developemnt Worksheet PDFDocument18 pagesBio 152 Lab 10 Animal Developemnt Worksheet PDFHyena100% (1)

- Module 5Document10 pagesModule 5Phan MhiveNo ratings yet

- B2603 ANIMAL DEVELOPMENT - Post Fertilization EventsDocument13 pagesB2603 ANIMAL DEVELOPMENT - Post Fertilization EventssispulieNo ratings yet

- CH 47 - Animal DevelopmentDocument70 pagesCH 47 - Animal DevelopmentSofiaNo ratings yet

- Developmental BiologyDocument72 pagesDevelopmental BiologyKshitija KavaliNo ratings yet

- Handouts in BioDocument8 pagesHandouts in BioEarl averzosaNo ratings yet

- Human Embryonic DevelopmentDocument8 pagesHuman Embryonic DevelopmentGargi BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Cell Parts and Its FunctionsDocument25 pagesCell Parts and Its FunctionsSen Armario100% (1)

- General Features of Chordate DevelopmentDocument66 pagesGeneral Features of Chordate DevelopmentJang WonyoungNo ratings yet

- 8.introduction To EmbryologyDocument63 pages8.introduction To EmbryologyAhmed OrabyNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 3. Photoperiodism and EmbryogenesisDocument7 pagesWorksheet 3. Photoperiodism and EmbryogenesisSukmagita RahajengNo ratings yet

- Fate Maps & Fate of Germ LayersDocument5 pagesFate Maps & Fate of Germ LayersAmar Kant JhaNo ratings yet

- Human Embryonic DevelopmentDocument16 pagesHuman Embryonic DevelopmentsivaNo ratings yet

- Principal Features of Development: 1. Fertilization/ Insemination/pollination/ Fecundation/ Syngamy and ImpregnationDocument6 pagesPrincipal Features of Development: 1. Fertilization/ Insemination/pollination/ Fecundation/ Syngamy and ImpregnationHashim khanNo ratings yet

- Unit Morphogenesis and Tissue Organis Ation: StructureDocument23 pagesUnit Morphogenesis and Tissue Organis Ation: Structurekaladhar reddyNo ratings yet

- Embryology Kul FKDocument65 pagesEmbryology Kul FKFahreza ArraisyNo ratings yet

- Phylum ARTHROPODADocument10 pagesPhylum ARTHROPODAKhawar HussainNo ratings yet

- Fertilization - ImplantationDocument4 pagesFertilization - ImplantationEzeoke ChristabelNo ratings yet

- Fertilization 1 1Document219 pagesFertilization 1 1Edwin TiuNo ratings yet

- Oogenesis Oogenesis Is The Process Whereby Oogonia Differentiate Into Mature Oocytes. It Starts in TheDocument7 pagesOogenesis Oogenesis Is The Process Whereby Oogonia Differentiate Into Mature Oocytes. It Starts in ThebarbacumlaudeNo ratings yet

- Research - Blastula StageDocument5 pagesResearch - Blastula StageAjay Sookraj RamgolamNo ratings yet

- Glossary - Zoology - : Biophysics - Sbg.ac - At/home - HTMDocument37 pagesGlossary - Zoology - : Biophysics - Sbg.ac - At/home - HTMPepe CaramésNo ratings yet

- Cleavage Partitions The Zygote Into Many Smaller CellsDocument10 pagesCleavage Partitions The Zygote Into Many Smaller CellssispulieNo ratings yet

- Biology ProjectDocument21 pagesBiology ProjectsivaNo ratings yet

- Human Embryology: Presenting By: Ms.G.Nivedhapriya M, SC ., Nursing Sripms-Con CoimbatoreDocument74 pagesHuman Embryology: Presenting By: Ms.G.Nivedhapriya M, SC ., Nursing Sripms-Con CoimbatoreKavipriyaNo ratings yet

- 4 FertilizationDocument389 pages4 FertilizationAngel Gabriel Fornillos100% (1)

- Mikes First Semester Embryology-1Document8 pagesMikes First Semester Embryology-1obianujuonyeka6No ratings yet

- 3 Animal TissuesDocument21 pages3 Animal TissuesAnonymous KazutoNo ratings yet

- Review of Fetal DevelopmentDocument71 pagesReview of Fetal DevelopmentlisafelixNo ratings yet

- Embryonic Development - WikipediaDocument7 pagesEmbryonic Development - WikipediadearbhupiNo ratings yet

- EmbryologyDocument101 pagesEmbryologytawandarukwavamadisonNo ratings yet

- Origin and Development of Organ Systems NotesDocument4 pagesOrigin and Development of Organ Systems NotesimnasNo ratings yet

- Insect BodywallDocument3 pagesInsect BodywallDillawar KhanNo ratings yet

- Camp's Zoology by the Numbers: A comprehensive study guide in outline form for advanced biology courses, including AP, IB, DE, and college courses.From EverandCamp's Zoology by the Numbers: A comprehensive study guide in outline form for advanced biology courses, including AP, IB, DE, and college courses.No ratings yet

- Physiology of Reproduction (2019) Notes:: Provided by Yvonne HodgsonDocument14 pagesPhysiology of Reproduction (2019) Notes:: Provided by Yvonne HodgsonBảoChâuNo ratings yet

- Pembentukan Lapisan-Lapisan Bakal Dan SelomDocument35 pagesPembentukan Lapisan-Lapisan Bakal Dan SelomRosihan Husnu MaulanaNo ratings yet

- اجنه الاخصابDocument12 pagesاجنه الاخصابFatimaAmmarNo ratings yet

- Frog EmbryologyDocument8 pagesFrog EmbryologyklumabanNo ratings yet

- FertilizationDocument2 pagesFertilizationDua SlmNo ratings yet

- 07 Gastrulation BiologyDocument22 pages07 Gastrulation BiologyKashif JamalNo ratings yet

- Tissue EngineeringDocument15 pagesTissue Engineeringsattyadev95No ratings yet

- Why Do Cells Have Organelles?Document43 pagesWhy Do Cells Have Organelles?Zemetu Gimjaw AlemuNo ratings yet

- EmbryologyDocument9 pagesEmbryologyRuhul Qudus NaimNo ratings yet

- Notes For Cell Biology BT-I YearDocument16 pagesNotes For Cell Biology BT-I YearKRATIKA TYAGINo ratings yet

- Dkp1 Imam Agus Faisal 1.A. Stage or Phase Embriogenesis and OrganogenesisDocument3 pagesDkp1 Imam Agus Faisal 1.A. Stage or Phase Embriogenesis and OrganogenesisImam Agus FaisalNo ratings yet

- Uni FileDocument17 pagesUni Filemuqadar khanNo ratings yet

- Animal - Development (Kel 1-5)Document83 pagesAnimal - Development (Kel 1-5)MelatiNo ratings yet

- Local Media8080976868035007820Document19 pagesLocal Media8080976868035007820Kin elladoNo ratings yet

- Bology in Human Welfare (8M)Document11 pagesBology in Human Welfare (8M)kondamudiananyaNo ratings yet

- Bruno Callegaro - Embriologia (EN)Document8 pagesBruno Callegaro - Embriologia (EN)Jose TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Hairwellbeingfinal 1592394575686Document10 pagesHairwellbeingfinal 1592394575686enzooo2009No ratings yet

- Module-1 CP-1 Revised 2023Document42 pagesModule-1 CP-1 Revised 2023Deron C. De CastroNo ratings yet

- Arthropods: ENT 425 - Worksheet #1Document9 pagesArthropods: ENT 425 - Worksheet #1Evana N. PertiwiNo ratings yet

- Anexo 1 - Capitulo 139 Integrated Pest ManagementDocument6 pagesAnexo 1 - Capitulo 139 Integrated Pest ManagementJulian Andres Tovar MedinaNo ratings yet

- Phylum Arthropoda-2 Subphylum Crustacea: Ana Huamantinco Araujo 2018Document34 pagesPhylum Arthropoda-2 Subphylum Crustacea: Ana Huamantinco Araujo 2018Joselyn CarmenNo ratings yet

- Insect Morphology and Systematics PDFDocument182 pagesInsect Morphology and Systematics PDFYashraj Singh BhadoriyaNo ratings yet

- Entomology MergedDocument226 pagesEntomology MergedShanmathiNo ratings yet

- EntomologyDocument82 pagesEntomologySALAUDEEN SAEFULLAHNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Zoology: Lepidoptera, Moths and ButterfliesDocument578 pagesHandbook of Zoology: Lepidoptera, Moths and ButterfliesKarina SjNo ratings yet

- NTS Test Preparations Dogar Brothers Books in PDF 2018Document186 pagesNTS Test Preparations Dogar Brothers Books in PDF 2018Shahroz AsifNo ratings yet

- एपिस मेलीफेरा अनुसन्धान निर्देशिका (कोलोस वी वुक, भाग एक २०१३) for Nepalese Bee ScientistsDocument630 pagesएपिस मेलीफेरा अनुसन्धान निर्देशिका (कोलोस वी वुक, भाग एक २०१३) for Nepalese Bee ScientistsHarihar Adhikari100% (2)

- Module 2 PDFDocument98 pagesModule 2 PDFPrathmesh Bharuka100% (1)

- InsectDocument27 pagesInsectdeafrh4No ratings yet

- Insect StructureDocument37 pagesInsect StructureSaroj k jenaNo ratings yet

- AEB 317 Introductory Entomology-2Document88 pagesAEB 317 Introductory Entomology-2Ogualu FavourNo ratings yet

- Morphology of InsectDocument31 pagesMorphology of InsectSera Esra PaulNo ratings yet

- Hair and Hair Care (Dale H. Johnson)Document801 pagesHair and Hair Care (Dale H. Johnson)Amira AlaydrusNo ratings yet

- Phylum ProtozoaDocument123 pagesPhylum Protozoaยุทธพงษ์ สานต์ศิริNo ratings yet

- Structure and Functions of Insect Body Wall: Arun Kumar K M I Ph.D. Agricultural Entomology UAS, GKVK, BengaluruDocument19 pagesStructure and Functions of Insect Body Wall: Arun Kumar K M I Ph.D. Agricultural Entomology UAS, GKVK, Bengalurudeep khattraNo ratings yet

- Arthropod GlossaryDocument10 pagesArthropod GlossaryAlejandro Delgado BaltazarNo ratings yet

- Entomology Lab HandoutsDocument13 pagesEntomology Lab Handoutshumanupgrade100% (1)

- WoolDocument20 pagesWoolNasir Sarwar100% (1)

- CAMC 102 - General Physiology and ToxicologyDocument6 pagesCAMC 102 - General Physiology and ToxicologyPrincess Mae AspuriaNo ratings yet

- NO. 59. Finke, MD. (Persentase Kitin Serangga) Estimate of Chitin in Raw Whole InsectsDocument11 pagesNO. 59. Finke, MD. (Persentase Kitin Serangga) Estimate of Chitin in Raw Whole InsectsVincent AriesNo ratings yet

- Application of Enzymes and Chitosan Biopolymer To The Antifelting Finishing ProcessDocument6 pagesApplication of Enzymes and Chitosan Biopolymer To The Antifelting Finishing ProcessDesyree VeraNo ratings yet

- Insect Physiology and AnatomyDocument101 pagesInsect Physiology and AnatomySaid H AbdirahmanNo ratings yet