Professional Documents

Culture Documents

According To Gaudiya Vaishnava Literature

Uploaded by

IshikaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

According To Gaudiya Vaishnava Literature

Uploaded by

IshikaCopyright:

Available Formats

According to Gaudiya Vaishnava literature,

Chaitanya picked six disciples who came to be called the

Goswamis and established them at Vrindavan over the

course of the sixteenth century.

At his behest, the six Goswamis,

who were the second generation of Gaudiya Vaishnava

leaders,

compiled the body of theological texts that had come to

define their religious tradition.

In the wake of Chaitanya’s demise and the waning

popularity of the Gaudiya Vaishnava movement,

the Goswamis chose Srinivasa Acharya, slated to become

the next Gaudiya Vaishnava leader,

to redeploy their energies in Bengal.

He was provided a cartload of manuscripts inscribed with

the essential principles of the tradition to help him

accomplish this task.

While travelling through Bishnupur,

Srinivas lost these precious manuscripts placed under his

charge.

On tracing them to the local chief, Bir Hambir of the

Malla dynasty,

he visited Bishnupur and electrified the court by astutely

narrating and elucidating on episodes from Krishna’s life.

The raja was so deeply moved by Srinivas’s passion for

Krishna that he fell at his feet and confessed to having

arranged the theft of the manuscripts, mistaking them for

worldly treasures.

In a bid to make amends, Bir Hambir entreated Srinivasa

and his fellow devotees to stay on and granted them the

land and resources to create a sacred centre for

Vaishnava devotion in the region.

This narrative, recovered from various Gaudiya

Vaishnava texts, draws attention to Bishnupur’s political

patronage of the Gaudiya Vaishnava faith, which helped

the order flourish in this region and establish a seat of

culture and religion based on the Vaishnava tradition.

This alliance with the political authorities of Bishnupur

meant that Gaudiya Vaishnavism would have a powerful

influence on the distinctive styles of art, craftsmanship,

and temple artistry that were on the verge of surfacing in

the region.

Structure and Design

Similar to the contouring of Vrindavan that had been

carried out in the sixteenth century by Chaitanya and the

Gaudiya Vaishnava devotees, temples burgeoned in

Bishnupur, constructed to establish the ritual worship of

images. The deities installed in these temples were named

after the icons worshipped and enshrined previously at

Vrindavan, notable examples being Madan Mohan,

Shyam Raya, Radha Raman, Keshto Raya, Madan Gopal,

Murali Mohan, Gopinath, and so forth. The narratives

surrounding their miraculous discovery and revelation are

also comparable to those of Vrindavan.

These temples were conspicuously distinct from the

Vrindavan temples—they were constructed on a new

ratna style, reoriented to face south, departing from the

nāgara custom of north India and the rekha style of facing

east in the direction of the rising sun (Ghosh 2005). They

had two storeys instead of one, with an additional shrine

stacked over the conventional sanctum on the lower level.

The shrine in the upper pavilion was reserved for special

occasions such as festivals, leaving the lower sanctum

available for daily worship. Novel also was the

presentation of the dual axes of worship—these temples

were provided with dual altars within the lower level

sanctum itself. One altar was constructed on the

traditional east-facing style of Hindu temples, and this

deity would be ministered to by the priests of the temple.

The other altar, which eventually came to hold greater

importance, faced south towards the courtyard and

nātmandir (entertainment hall), where devotees would

gather to sing praises to Krishna and his heroics, and

often spontaneously rise in dance during the ārati. This

new temple form served the various ritual needs of the

emerging Gaudiya Vaishnava community in Bengal.

Fig.3: Radha Shyaam temple. (Image by Amitabha

Gupta- https://amitabhagupta.files.wordpress.com/2012/

08/picture101.jpg )

Fig.4: Nandalal temple

The temples and monuments of Vrindavan drew heavily

from the imperial Mughal style of the late sixteenth

century. The architectural style of the Bishnupur temples,

however, derived from the tradition that had developed

under the sultanates that had ruled Bengal for the

previous four centuries—interior vaulting, pointed arches

with cusps, sturdy pillars with many facets, curved

cornices, and terracotta decoration (McCutchion 1972).

The continuities in the design style between these

temples and the Islamic architecture of Qadam Rasul, a

shrine constructed in 1519 in dedication to the footprints

of the Prophet at Gaur, is articulated through certain

shared features like the cubical base of the sanctum in

temples such as the Madan Mohan temple (1694) (Fig.1),

Shyam Raya temple (1643) (Fig.2), Radha Shyam temple

(1658) (Fig.3), Nandalal temple (seventeenth century)

(Fig.4), Radha Madhav temple (1747) (Fig.5), and so

forth. Certain adaptations were introduced to tailor the

structure to the needs of worship, such as the low

structure with three cusped arches supported by thick

faceted pillars at the entrance, rows of thin terracotta

surface ornamentation, and the basic plan of a central

chamber enclosed by shallow doorways.

Fig.5: Radha Madhav temple. (Image by Arnab

Dutta- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_temples_in_

Bishnupur#/media/File:Radhamadhab_Temple_Arnab_D

utta_2011.JPG )

Fig.6: Rasmancha

The temples also draw inspiration from the sloping

thatched huts of the region; the curved cornices of these

temples, a characteristic feature of this design, are

derived from the bent bamboo eaves of cottages in the

Bengali countryside. This feature occurs in combination

with a number of basic designs. There is the char-chala

design that consists of a four-sided roof coming to a point

on a square base. A similar but smaller roof may be

constructed on top of the char-chala like a tower to make

an at-chala. There is the do-chala or ek-bangla design,

which features a two-sided humped roof evocative of the

curved cornice on an elongated base. The Rasamancha in

Bishnupur is the earliest known temple in existence built

in the ‘bangla’ do-chala style (Fig.6). When two such do-

chala huts are attached one in front of the other, where

the front acts as a porch and the rear as a shrine, the

design is called jorbangla, as can be observed in the

similarly named Jor Bangla or Keshto Raya temple

(1655) (Fig.7). In the pancha ratna design, the roof is

flatter than in the do-chala or char-chala, and has a tower

in the centre which may be accompanied by four smaller

turrets at the four corners. The number of storeys may be

multiplied with the number of turrets in each corner from

one (ek-ratna) to 25 (panchabingshati-ratna)

(McCutchion 1972).

Fig. 7: Jor Bangla or Keshto Raya temple

Terracotta Decorations

Along with the innovations in form and structure, an

exceptional feature of this kind of temple architecture is

the use of terracotta facades. The temple walls are

covered with terracotta panels recounting the life and

exploits of Krishna, scenes from the Ramayana and the

Mahabharata, and stories from the Vishnupurana (Fig.8).

According to David McCutchion, the Bengal temple

terracotta art that developed from the sixteenth to the

nineteenth centuries, a development on the previous

sultanate architecture of the region, forms a self-

contained art tradition that is distinct from both the

preceding styles and the succeeding ones. McCutchion

says that even though terracotta decoration was in itself

not a new practice, the finely chiseled carpet-like

patterning of the terracotta facades of the Bishnupur

temples was vastly different from the style of terracotta

carving found in Buddhist monuments that used boldly

carved and modeled laterite bricks. Terracotta itself

ceased to be popular in the temple-building traditions of

the later Pala and Sena periods: their broad brickwork

acted as bases for stucco decoration alone.

Fig. 8: Panels with different carvings, Jor Bangla or

Keshto Raya

Fig. 9: Krishna with Gopis

Even though scenes from Krishna’s life were most

commonly sculpted on the terracotta plaques, there are

also depictions of scenes from other Vaishnava texts and

the larger body of the Vishnupurana, as well as legends

of other gods and goddesses. The terracotta work on the

Shyam Raya temple (1643), one of the oldest terracotta

temples in Bishnupur, is a fine example of this. This

temple has been constructed in the pancha-ratna style and

is the most richly decorated of all the terracotta temples

to be found in the region—every inch of the temple from

the interiors to the archway and from the vaulting inside

to the towers on the roof are sheathed with fine terracotta

work. There are innumerable small plaques embellished

with images based on themes such as Krishna embracing

Radha or playing his flute to her, Krishna’s battle with

Indra for the parijat tree, and Krishna between two gopis

under an elaborate canopy (Fig.9). These images are

bordered by a profusion of small rhythmic figures and

floral and vegetal motifs. Above the archways are

panoramic battle scenes depicting gods, demons,

warriors, and heroes. Scenes from Puranic legends, the

Ramayana, and Krishnalila adorn the rows below, and the

plaques at the very bottom depict more contemporary

scenes of the raja going to battle or proceeding in his

palanquin.

Fig. 10: Bhishma on a bed of arrows

The terracotta on the nearby Keshto Raya temple, also

famously known as the Jor Bangla temple, built only 12

years after the Shyam Raya temple and with the

patronage of the same raja, is just as lavish as its

predecessor. The subject matter is also largely similar,

but the layout is more intrepid and systematic. The

different rows of illustrations depict a single, linear

narrative each, with entire rows being taken up by

chronological depictions of Krishna’s life from the

nursing of Krishna and Balaram to Krishna and Balaram

fighting the King’s wrestlers in Mathura, warriors

confronting each other on chariots in the battle of

Kurukshetra highlighting evocative scenes like Bhishma

lying on a bed of arrows (Fig.10), scenes from the

Ramlila, and so forth.

The stories surrounding Krishna’a life and the legends

regarding his miraculous deeds were integral to the way

the Gaudiya Vaishnava movement unfolded and

proliferated in Bengal during the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries. The artistry displayed in the

terracotta temples is an indication that alongside

devotional songs and dramatic performances, a visual

vocabulary for communicating the episodes of Krishna’s

life also emerged. Manuscript copies of the Bhagavata

Purana, a text regarded as a revelation in the Vaishnava

tradition, were lavishly adorned with images depicting

these episodes, bringing to light the earliest efforts at

establishing pictorial conventions. These depictions

similarly came to adorn the brick surfaces of Krishna

temples in sixteenth and seventeenth century Bishnupur

—a visual narrative of the life story of the deity housed

in the temple (Ghosh 2005).

The temple imagery, by showing Krishna’s miraculous

feats, his dramatic and violent confrontations, and his

amorous encounters, created compelling visual sequences

meant for a largely illiterate audience. It may be

conjectured that the terracotta panels acted as visual aids

accompanying the narration of a priest or community

elder. The practice still exists whereby adults and guides

recount epic and Puranic tales to children and visitors,

using the panels to bring alive the scenes for the

listener’s imagination. Together with devotional music

and drama, the terracotta panels can be seen as part of a

collective artistic tradition that helped reinforce Gaudiya

Vaishnava narratives and the theological messages

embedded in them by evoking complete sensory

participation in the form of sight, sound, action, and

perhaps even smell and taste in the form of flowers and

offerings. The profusion of these images and their

selective deployment in the overall spread of the Gaudiya

Vaishnava faith reveal both an attempt to define the texts

and practices of the faith, as well as to put Bishnupur on

the map as an emerging centre for pilgrimage and

devotion during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The exact period of Gwalior Fort's construction is not certain but according to some old records

we get to know that Gwalior fort was initially known as Badal garh fort which was built by

a Sakarwar Rajput king name as Maharaja Badal Dev.[5] According to a local legend, the fort was

built by a local king named Suraj Sen (Sakarwar Rajput) in 3 CE. He was cured of leprosy, when

a sage named Gwalipa offered him the water from a sacred pond, which now lies within the fort.

The grateful king constructed a fort, and named it after the sage. The sage bestowed the title Pal

("protector") upon the king, and told him that the fort would remain in his family's possession, as

long as they bear this title. 83 descendants of Suraj Sen Pal controlled the fort, but the 84th,

named Tej Karan, lost it.

You might also like

- ROCK Temple ArchitectureDocument28 pagesROCK Temple ArchitectureUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Seam PuckeringDocument16 pagesSeam PuckeringIshika100% (2)

- Sabit Adanur - Handbook of Weaving-CRC Press (2000) PDFDocument427 pagesSabit Adanur - Handbook of Weaving-CRC Press (2000) PDFAnjani Deevi50% (2)

- Sabit Adanur - Handbook of Weaving-CRC Press (2000) PDFDocument427 pagesSabit Adanur - Handbook of Weaving-CRC Press (2000) PDFAnjani Deevi50% (2)

- Temple Mountains As A Design Concept of Temple ArchitectureDocument286 pagesTemple Mountains As A Design Concept of Temple Architectureuday100% (1)

- Renaissance Art and ScienceDocument14 pagesRenaissance Art and ScienceIshikaNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Art and ScienceDocument14 pagesRenaissance Art and ScienceIshikaNo ratings yet

- Aviation EnglishDocument34 pagesAviation EnglishElner Dale Jann Garbida100% (4)

- Famous Temples in Tamil NaduFrom EverandFamous Temples in Tamil NaduRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Bhuvaneshwari TempleDocument4 pagesBhuvaneshwari Templekb020sayanNo ratings yet

- The Styles of Temple Architectur EDocument27 pagesThe Styles of Temple Architectur EAnshika sainiNo ratings yet

- S7-300 - 400 Tip Analog Scaling Tip No. 1Document7 pagesS7-300 - 400 Tip Analog Scaling Tip No. 1mail87523No ratings yet

- THE ANCIENT INSCRIPTIONS OF RAMTEK HILLDocument35 pagesTHE ANCIENT INSCRIPTIONS OF RAMTEK HILLAndrey Klebanov100% (1)

- Ellora 14 - Chapter 6Document48 pagesEllora 14 - Chapter 6knarayananbhelNo ratings yet

- Spme-2 Final AssignmentDocument30 pagesSpme-2 Final AssignmentIshikaNo ratings yet

- Hindu Temple Architecture - WikipediaDocument30 pagesHindu Temple Architecture - WikipediaPallab ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Medieval Indian Temple Architecture - Synthesis and DigressionDocument9 pagesMedieval Indian Temple Architecture - Synthesis and Digressionrituag_bitmesra3888No ratings yet

- Ancient Temples KashmirDocument3 pagesAncient Temples KashmirShivaditya SinghNo ratings yet

- Agama Shilpa Parampara 2Document9 pagesAgama Shilpa Parampara 2Prantik GuptaNo ratings yet

- Stone Carved Temple in India.Document16 pagesStone Carved Temple in India.Kunal RaghwaniNo ratings yet

- Literature Review (Book) Creative WritingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review (Book) Creative WritingYATRI SHAHNo ratings yet

- Regionalism Art and Architecture of The Regional Styles (North India)Document15 pagesRegionalism Art and Architecture of The Regional Styles (North India)T Series Ka BapNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19 Temple ArchitectureDocument5 pagesChapter 19 Temple ArchitectureAyushi JhaNo ratings yet

- The Hindu - Arts - Books - Epigraphical Study of Vishnu Temples of KanchiDocument2 pagesThe Hindu - Arts - Books - Epigraphical Study of Vishnu Temples of KanchikaushiksasNo ratings yet

- UNIT 17Document13 pagesUNIT 17Sheel JohriNo ratings yet

- Earliest Concrete Evidence of Architecture in IndiaDocument6 pagesEarliest Concrete Evidence of Architecture in IndiaAyush Agrawal 19110143No ratings yet

- Rock Cut ArchitectureDocument7 pagesRock Cut ArchitecturetejaswaniNo ratings yet

- Temple Architecture, C. 300 - 750 CE: Cultural DevelopmentDocument25 pagesTemple Architecture, C. 300 - 750 CE: Cultural DevelopmentShreosi BiswasNo ratings yet

- Kefa 106Document35 pagesKefa 106Anushka GargNo ratings yet

- Hindu and Indian ArchitectureDocument7 pagesHindu and Indian ArchitectureMj JimenezNo ratings yet

- Inspection Note - RewaDocument14 pagesInspection Note - Rewamadhulikarkhabar7297No ratings yet

- Badami Chalukya Architecture and Cave TemplesDocument2 pagesBadami Chalukya Architecture and Cave TemplesShruthi ArNo ratings yet

- Architecture Art StylesDocument8 pagesArchitecture Art Stylespratyusha biswas 336No ratings yet

- Religion Shapes Interior DesignDocument41 pagesReligion Shapes Interior DesignHarshita Saini100% (1)

- Jain ArchitectureDocument9 pagesJain ArchitectureSuhaniNo ratings yet

- Gandhara Art and ArchitectureDocument7 pagesGandhara Art and Architecturesnigdha mehraNo ratings yet

- Article StudyontheSanchiStupaRuinsDocument6 pagesArticle StudyontheSanchiStupaRuinsEknoor Singh 4No ratings yet

- SubarnapurDocument24 pagesSubarnapursamj18992No ratings yet

- Vijayanagara Architecture Research Paper 3Document12 pagesVijayanagara Architecture Research Paper 3Sarganisha BNo ratings yet

- Chola Temples UPSC Arts and Culture NotesDocument5 pagesChola Temples UPSC Arts and Culture NotesmanjuNo ratings yet

- Karnataka Paradise PDFDocument10 pagesKarnataka Paradise PDFLokesh BangaloreNo ratings yet

- Pallava Architecture and SculptureDocument30 pagesPallava Architecture and SculptureSamudrala SreepranaviNo ratings yet

- Art & Architecture of South & Southeast Asia before 1200Document42 pagesArt & Architecture of South & Southeast Asia before 1200CabatanganDhggmhsNo ratings yet

- Sanchi Visit FileDocument19 pagesSanchi Visit FileYash MalviyaNo ratings yet

- Origin and Genesis of the Madurai Meenakshi Sundareswarar TempleDocument40 pagesOrigin and Genesis of the Madurai Meenakshi Sundareswarar TempleRajeshwaran KaruppiahNo ratings yet

- THE GLIMPSE OF THE MAGNIFICANCE OF A LOST CITY (AutoRecovered)Document8 pagesTHE GLIMPSE OF THE MAGNIFICANCE OF A LOST CITY (AutoRecovered)Vaishali DhyaniNo ratings yet

- Ancient Buddhist cave architectureDocument20 pagesAncient Buddhist cave architectureAkhilSharmaNo ratings yet

- Stupa ArchitectureDocument8 pagesStupa Architectureramish mushfiqNo ratings yet

- Architecture of Kēra A Temples: Remya V.PDocument9 pagesArchitecture of Kēra A Temples: Remya V.PAnirban MazumderNo ratings yet

- Jabs0208-013cv VBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBGBBBBBBBBBBBDocument2 pagesJabs0208-013cv VBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBGBBBBBBBBBBBChaitanya SharmaNo ratings yet

- UNIT 18Document17 pagesUNIT 18Sheel JohriNo ratings yet

- CCRT Art and Culture Notes: Visual ArtsDocument11 pagesCCRT Art and Culture Notes: Visual ArtsTriranga BikromNo ratings yet

- Indian Temple Architecture: Devanshu .D. Veshviker Roll No. 65 Submitted To-Bharti Teacher Class - 10 - CDocument30 pagesIndian Temple Architecture: Devanshu .D. Veshviker Roll No. 65 Submitted To-Bharti Teacher Class - 10 - CShiwangi NagoriNo ratings yet

- Early Temples in BadamiDocument9 pagesEarly Temples in BadamiSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- History of Big Temple, Thanjavur and Its Consecration - A StudyDocument8 pagesHistory of Big Temple, Thanjavur and Its Consecration - A StudyManju Akash J KNo ratings yet

- 13 Chapter 4Document42 pages13 Chapter 4indrani royNo ratings yet

- North Indian Temple Architecture from 800 ADDocument19 pagesNorth Indian Temple Architecture from 800 ADABHISHNo ratings yet

- 001-Chennakeshava Temple, SomanathapuraDocument12 pages001-Chennakeshava Temple, SomanathapuraraajagopalNo ratings yet

- He Architecture of BengaDocument2 pagesHe Architecture of BengaRohini PandeyNo ratings yet

- ModuleDocument5 pagesModuleManasa KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Kailash Temple, Ellora: Rock-Cut Hindu Ellora Maharashtra India MegalithDocument2 pagesKailash Temple, Ellora: Rock-Cut Hindu Ellora Maharashtra India MegalithFahim Sarker Student100% (1)

- Socio Cultural Factors Affecting Evolution of Kanlinga Temple ArchitectureDocument13 pagesSocio Cultural Factors Affecting Evolution of Kanlinga Temple Architecturesanchita sahuNo ratings yet

- Architecture: Early&ClassicalDocument38 pagesArchitecture: Early&ClassicalSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Prominent Religious Monuments and Sites in Bundelkhand RegionDocument3 pagesProminent Religious Monuments and Sites in Bundelkhand RegionGaurav MishraNo ratings yet

- From Sikhara To Sekhari Building From THDocument16 pagesFrom Sikhara To Sekhari Building From THsham_codeNo ratings yet

- Time Study Uses and ProcedureDocument14 pagesTime Study Uses and ProcedureIshikaNo ratings yet

- CHAPPERS MAMTA VAGHADIA GP May 2017Document72 pagesCHAPPERS MAMTA VAGHADIA GP May 2017IshikaNo ratings yet

- IE Jury Ishika MaluDocument16 pagesIE Jury Ishika MaluIshikaNo ratings yet

- Operation Breakdown of ShortsDocument3 pagesOperation Breakdown of ShortsIshikaNo ratings yet

- Levi S Casual Shirt Operation BreakdownDocument25 pagesLevi S Casual Shirt Operation BreakdownIshikaNo ratings yet

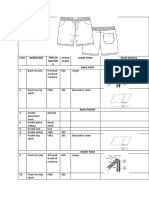

- Pattern Making Assignment-2 Specification Sheet: Bachelor'S of Fashion TechnologyDocument11 pagesPattern Making Assignment-2 Specification Sheet: Bachelor'S of Fashion TechnologyIshikaNo ratings yet

- Colorful Modern Geometric Construction ResumeDocument1 pageColorful Modern Geometric Construction ResumeIshikaNo ratings yet

- Study of Ergonomics in Textile Industry: Nemailal TarafderDocument9 pagesStudy of Ergonomics in Textile Industry: Nemailal TarafderSAURAV KUMARNo ratings yet

- Why Sewing MachineDocument17 pagesWhy Sewing MachineIshikaNo ratings yet

- FGF Study MaterialDocument30 pagesFGF Study MaterialIshikaNo ratings yet

- Brown Scrapbook Travel Square Photo BookDocument22 pagesBrown Scrapbook Travel Square Photo BookIshikaNo ratings yet

- Two Piece Dress Block Bodice Back Size 10 / Scale 1:4 Two Piece Dress Block Bodice Front Size 10 / Scale 1:4Document1 pageTwo Piece Dress Block Bodice Back Size 10 / Scale 1:4 Two Piece Dress Block Bodice Front Size 10 / Scale 1:4IshikaNo ratings yet

- I A M - F F D G: Solates Pplication of Ulti Unctional Inishes ON Enim ArmentsDocument9 pagesI A M - F F D G: Solates Pplication of Ulti Unctional Inishes ON Enim ArmentsIshikaNo ratings yet

- IDM-DT GroupAssignment 1 D H IDocument46 pagesIDM-DT GroupAssignment 1 D H IIshikaNo ratings yet

- 5 LevisJFMM200484Document11 pages5 LevisJFMM200484Anamaria Mihaela SîrghiNo ratings yet

- Brown Scrapbook Travel Square Photo BookDocument22 pagesBrown Scrapbook Travel Square Photo BookIshikaNo ratings yet

- Pass 2011Document6 pagesPass 2011Ara Grace M. MonsantoNo ratings yet

- 5 LevisJFMM200484Document11 pages5 LevisJFMM200484Anamaria Mihaela SîrghiNo ratings yet

- Marketing of Fashion - BFTech PDF For StudentsDocument111 pagesMarketing of Fashion - BFTech PDF For StudentsIshikaNo ratings yet

- I A M - F F D G: Solates Pplication of Ulti Unctional Inishes ON Enim ArmentsDocument9 pagesI A M - F F D G: Solates Pplication of Ulti Unctional Inishes ON Enim ArmentsIshikaNo ratings yet

- 5 LevisJFMM200484Document11 pages5 LevisJFMM200484Anamaria Mihaela SîrghiNo ratings yet

- Colorful Modern Geometric Construction ResumeDocument1 pageColorful Modern Geometric Construction ResumeIshikaNo ratings yet

- 02.properties or Characteristics of SeamDocument2 pages02.properties or Characteristics of SeamIshikaNo ratings yet

- Mosai JLPT Application FormDocument1 pageMosai JLPT Application FormscNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Materials Development, Multilingual Education, Mother Tongue-Based MultilingualDocument22 pagesKeywords: Materials Development, Multilingual Education, Mother Tongue-Based MultilingualMar Jhon AcoribaNo ratings yet

- Analisis Pemasaran Buah Naga di BanyuwangiDocument18 pagesAnalisis Pemasaran Buah Naga di BanyuwangiAna RainasiarNo ratings yet

- The Starter Generator" - 40+ engaging lesson starters"Over 40 lesson starters to spark discussion" "Generate discussion with 40+ creative starters""Mix it up with 40 engaging discussion startersDocument43 pagesThe Starter Generator" - 40+ engaging lesson starters"Over 40 lesson starters to spark discussion" "Generate discussion with 40+ creative starters""Mix it up with 40 engaging discussion starterskathrynbrinnNo ratings yet

- AspectDocument11 pagesAspectSaiful HudaNo ratings yet

- Alexander Theroux Answers Charge of Plagiarism in Primary Colors - San Diego ReaderDocument21 pagesAlexander Theroux Answers Charge of Plagiarism in Primary Colors - San Diego ReaderPahomy4100% (1)

- It Will Make More SpaceDocument62 pagesIt Will Make More Spaceapi-274335541No ratings yet

- Kelas 7 Semester 2Document22 pagesKelas 7 Semester 2Shiinta P AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Research Problems, Variables, and HypothesesDocument7 pagesResearch Problems, Variables, and Hypotheseselaineidano100% (1)

- BDU Thesis and Dissertation Formating Guideline - RevisedDocument27 pagesBDU Thesis and Dissertation Formating Guideline - RevisedEdlamu Alemie80% (5)

- Caning Dictionary Jun 16Document36 pagesCaning Dictionary Jun 16Hakki YazganNo ratings yet

- Math in Our World 2Nd Edition by Sobecki Solution Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesMath in Our World 2Nd Edition by Sobecki Solution Manual Full Chapter PDFtom.fox777100% (11)

- Envisalinktpi Ademco 1 02Document10 pagesEnvisalinktpi Ademco 1 02Sergio GarciaNo ratings yet

- LIT 4 Final TestDocument3 pagesLIT 4 Final TestMIKEL BAINTONo ratings yet

- Product MetrixDocument26 pagesProduct MetrixtmonikeNo ratings yet

- Bahasa InggrisDocument4 pagesBahasa Inggrisilham cahyadiNo ratings yet

- IntroductiontoMATLAB PDFDocument30 pagesIntroductiontoMATLAB PDFncharalaNo ratings yet

- 8000002080-Installation On Linux OS - Cloud Connector - PRDDocument4 pages8000002080-Installation On Linux OS - Cloud Connector - PRDKapil NebhnaniNo ratings yet

- CSC111 Study Questions by Premier.-1Document9 pagesCSC111 Study Questions by Premier.-1Abraham BanjoNo ratings yet

- R07 SET-1: Code No: 07A6EC04Document4 pagesR07 SET-1: Code No: 07A6EC04Jithesh VNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence High Technology PowerPoint TemplatesDocument48 pagesArtificial Intelligence High Technology PowerPoint TemplatesainnaayNo ratings yet

- W3 MapehDocument12 pagesW3 Mapehdianne grace incognitoNo ratings yet

- Operating System 5Document34 pagesOperating System 5Seham123123No ratings yet

- KAK English Year 1-6Document4 pagesKAK English Year 1-6Syazwani SeliNo ratings yet

- Assignment - V Construction of Words and PhrasesDocument2 pagesAssignment - V Construction of Words and PhrasesJashen TangunanNo ratings yet

- Lemery Colleges, Inc.: College DepartmentDocument8 pagesLemery Colleges, Inc.: College DepartmentHarrenNo ratings yet

- Textus ReceptusDocument20 pagesTextus ReceptusKatty UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- P1 AndalusiaDocument1 pageP1 Andalusiatiron4No ratings yet