Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 129.237.35.237 On Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

Uploaded by

api-550243992Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 129.237.35.237 On Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

Uploaded by

api-550243992Copyright:

Available Formats

Effects of Wh-Question Graphic Organizers on Reading Comprehension Skills of

Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Author(s): Keri S. Bethune and Charles L. Wood

Source: Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities , June 2013,

Vol. 48, No. 2 (June 2013), pp. 236-244

Published by: Division on Autism and Developmental Disabilities

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23880642

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Education and Training

in Autism and Developmental Disabilities

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 2013, 48(2), 236-244

© Division on Autism and Developmental Disabilities

Effects of Wh-Question Graphic Organizers on

Reading Comprehension Skills of Students with

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Ken S. Bethune Charles L. Wood

James Madison University University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Abstract: Students with autism spectrum disorders often have difficulty with reading comprehension. This study

used a delayed multiple baseline across participants design to evaluate the effects of graphic organizers on the

accuracy of wh-questions answered following short passage reading. Participants were three elementary-age

students with autism spectrum disorder. Results indicated improved accuracy of responses to wh-questions,

generalization, and maintenance of gains following intervention. Implications for future research and practice

are discussed.

Many students with autism spectrum disorders Several researchers have examined ways to

(ASD) acquire reading decoding skills, but teach reading comprehension to students

continue to struggle with reading comprehen- with ASD. Chiang and Lin (2007) conducted a

sion (Nation, Clarke, Wright, & Williams, literature review to investigate reading com

2006). Comprehension occurs when the prehension strategies for students with ASD.

reader actively obtains meaning from written They included 11 studies that examined par

text (Bursuck & Darner, 2011). Newman et al. ticipants, setting, text (academic reading)

(2007) found that students with ASD had sta- comprehension, functional sight words, com

tistically significant lower scores on reading prehension, and instructional methods. Re

comprehension compared to scores by their viewed studies included 49 students with ASD

typically developing peers, even when control- (many of whom also were diagnosed with an

ling for sight word recognition. Saalasti and intellectual disability) who were 3 to 17 years

colleagues (2008) showed that students with old. Four studies occurred in traditional

Asperger syndrome had significantly lower schools (two in inclusion classrooms), three in

scores on a comprehension of instructions private clinics or specialized schools, one in a

subtest compared to scores of their typically home setting, and three studies did not spec

developing peers. Walberg and Magliano ify the setting. Four studies examined text

(2004) identified possible reasons for the dis- comprehension and the remaining seven

crepancy between word reading and compre- studies examined sight word comprehension,

hension skills for students with ASD: (a) in- A wide variety of instructional methods were

ability to use background knowledge to represented including progressive time-delay,

interpret information and ambiguities pre- discrete-trial training, peer tutoring, coopera

sented in text, (b) fundamental deficits in live learning groups, incidental teaching,

language abilities, (c) difficulties with linguis- computer-assisted instruction, priming, use of

tic processing at the sentence level, and (d) in- a cloze task (filling in blanks), and cueing

ability to resolve ambiguity in text. students to attend. The authors stated that

future research needs to apply National Read

ing Panel (2000) identified strategies for in

Correspondence concerning this article should structing students with ASD, further explora

be addressed to Charles L. Wood, Department of tion of literacy instruction of students with

Special Education and Child Development, 9201 Asperger syndrome, and further research on

University City Blvd., Charlotte, NC 29223. E-mail: instructional methods for teaching reading

clwood@uncc.edu comprehension to students with high func

236 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-June 2013

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

tioning autism or Asperger syndrome in the strategy on reading comprehension test

general education setting. scores. They used a multiple probe across par

Other studies have examined reading com- ticipants design with four phases to anal

prehension skills of students with ASD. First, the impact of teaching the test-taking strat

Reynhout and Carter (2008) studied the ef- to students with high-functioning ASD.

fects of a social story intervention on appro- suits showed a functional relation between a

priate group reading behavior and specific quisition of the test-taking strategy and

attention on reading comprehension difficul- increase in reading comprehension test

ties. They used a single-subject, ABC design to scores. Results also demonstrated gener

evaluate the impact of the social story review tion and maintenance of the test-taking str

prior to group read aloud on the behavior of egy.

looking at the book. The participant was an Finally, Hundert and van Delft (2009) u

8-year-old diagnosed with ASD, intellectual a multiple probe across behaviors design

disability, and limited language skills. The re- analyze the effects of a system of least promp

suits failed to demonstrate a functional rela- on students' ability to answer three types of

tion between the social story and appropriate ferential "why" questions: (a) questions based

group reading behavior. The targeted behav- on a three-card picture sequence (a vi

ior also failed to improve after adding a verbal representation of a short sequence of event

prompt to read the story. The authors suggest paired with a short text), (b) questions base

that one possible explanation for the lack of a on a vocally presented story, and (c) genera

functional relation could be that the partid- information questions. Participants w

pant was unable to comprehend the social three children with high functioning auti

story text and/or the text being read to the Results showed a functional relation between

class. The authors stated that future research the embedded instruction and the students'

is needed to examine comprehension skills ability to answer the three identified types

that act as prerequisites to social stories and to of inferential "why" questions; however, stu

implement rigorous designs including multi- dents' responses did not generalize to u

ple baseline across behaviors, settings, or par- trained inferential "why" questions. One nota

ticipants. ble limitation of this study is the insufficient

Flores and Ganz (2007) analyzed the effects baseline data collected pr

of a Direct Instruction (DI) reading program tion of intervention. At

on reading comprehension skills. DI involves sufficient data to establ

carefully designed explicit instruction, scripted other times an increa

lessons, high rates of student responses, and lished in baseline. The a

immediate feedback (Watkins & Slocum, future research is needed to

2004). DI has been successful with students results in school settings during classroom

with disabilities and students at risk for failure routines and implemented by general educa

(Bursuck & Darner, 2011; Camine, Silbert, tion teachers, special education teachers, or

Kame'enui, & Tarver, 2010). They used a mul- paraprofessionals. The authors also stated that

tiple probe across behaviors design to mea- further research is needed to determine if an

sure the impact of DI on reading comprehen- increase in ability to answer inferential "why"

sion skills and behaviors of students with questions would translate into an increase in

developmental disabilities, including ASD. Re- overall reading comprehension skills,

suits showed a functional relation between One method suggested for increasing read

DI and reading comprehension skills. The ing comprehension skills for struggling read

authors stated that future research is needed ers (e.g., students with learning disabilities) is

to examine the effects of the complete DI graphic organizers (Jiang & Grabe, 2007).

program (rather than just the selected por- Graphic organizers are visual representations

tions used in this study), the modifications of the information conveyed in a text (Jiang &

needed for students with ASD, and feasibility Grabe, 2007). Graphic organizers have been

of implementation of this program. used to increase reading comprehension skills

Songlee, Miller, Tincani, Sileo, and Perkins in young readers and second language stu

(2008) examined the effects of a test-taking dents (Jiang & Grabe, 2007). Graphic organiz

Graphic Organizers / 237

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ers are currently in wide use by reading ex- mentary school in a separate classroom de

perts and classroom teachers, and studies have signed for children with autism due to a corn

shown a positive effect on reading compre- bination of his challenging behaviors, such as

hension (Carnine et al., 2010; Jiang & Grabe, aggression, tantrums, and lack of academic

2007). progress. Aaron's IQ was tested with the Reyn

Graphic organizers and visual supports have olds Intellectual Assess

also been recommended to teach reading ported as 94. Aaron wa

comprehension skills to students with ASD ¡n conversational lan

(Gately, 2008). Visually cued instruction, in- person was of inter

eluding graphics, story/visual maps, and goal most often used his la

structure mapping, can help students with wants and needs. Aa

ASD focus on key information, increase inde- struction using a l

pendence and memory (Gately, 2008). Al- program. The teache

though graphic organizers and visual supports Aaron could read

have been successful teaching reading com- fluently, he was una

prehension skills to nondisabled young read- sion questions abou

ers, and have been recommended as an effec- Mark was a 10-yea

tive teaching tool for students with ASD, autism and was Cauca

further empirical research is needed to dem- same public elemen

onstrate its use to teach reading comprehen- was placed in a diff

sion to students with ASD. Therefore, the pur- designed for childre

pose of this study was to examine the effects of onstrated severely r

wh-question (i.e., who, what, where, what do- reoCypit behavio

ing) graphic organizers on reading compre- demk Mark

hension skills in students with ASD. ^ , ct- , ui * n

reported as o7. Mark was able to vo

municate his wants and needs and r

Method some intraverbal questions (e.g., "What's on

your head?" "A hat."). Mark was begi

Participants read sentences and paragraphs, but his flu

~ . . . . ^ , ency and intonation were not yet mastered.

Participants were three elementary students 7 , 7

j . , «or* i j * * r» Mark s teacher reported that Mark was unable

diagnosed with ASD who demonstrated deh- r

. . r j • u to answer any comprehension questions about

cits in the area of reading comprehension. / r n

Convenience sampling was used to identify a Passa8e he had

(a) ability to orally read text at a minimum of Joe was a 10-year-

a 1st grade level, (b) ability to match written nosed with autism a

nouns to picture representations, (c) inability Joe also attended th

to accurately answer literal wh-questions (who, school and was

what, where, and what doing) about a previ- designed to meet

ously read text, (d) inability to sort written autism. Joe demonst

text into a graphic organizer according to the and stereotypic

corresponding type of literal wh-question 'n academic progr

(who, what, where, and what doing), and some limitations in

(e) signed parental consent and student as- difficult to under

sent. Although the participants of this study tion. Joe demonstra

represent a range of races and ethnicities, language; however,

participants were not selected based on race phrases, gestures, and

or ethnicity, rather this range was the result of his wants and nee

the convenience sampling used to identify the Leiter Intern

participants meeting the above criteria. and was reported as

Aaron (pseudonyms used throughout) was sentences and pa

an 8-year-old boy diagnosed with autism and he read aloud it w

was Hispanic. Aaron attended a public ele- his speech. The teacher reported Joe was

238 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-June 2013

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

unable to answer comprehension questions student wrote the word "mom" into the "who"

about passages he had read. category. When presented with the word "run

ning," the response was scored correct if the

student wrote "running" in the "what doing"

Setting

category. This resulted in the student having a

The study took place in a public elementary completed graphic organizer where key text

school located in an urban area of the south- from the story was sorted into the appropriate

eastern United States. Instruction occurred at categories.

the students' desk or at a designated reading The primary dependent variable was accu

instruction table in each student's classroom. racy answering eight, literal recall (i.e., stated

The classrooms were each designed specifi- in the text) wh-comprehension questions,

cally for students with autism, but were not This occurred after the student completed the

otherwise modified for this study. Each class- graphic organizer. The eight questions corn

room was staffed with one special education prised two questions from each category: who,

teacher and one paraprofessional. The first what, where, and what doing. The researcher

author served as the experimenter and con- asked two questions of each type to ensure

ducted the intervention and probes through- that students had to respond according to the

out the study. A graduate student from a local type of information requested and ensure that

university served as a data collector for inter- the response was correct according to the pas

observer reliability and procedural fidelity. sage. For example, if the passage read "Nancy

played with dolls on the floor. Mom cooked

dinner in the kitchen." The student would

Materials

have sorted "Nancy" and "mom" into the

The graphic organizer was an 8.5" by 11" pa- "who" category and "floor" and "kitchen" i

per divided into four columns. Each column the "where" category of the graphic organi

was labeled in large font according to the type Students had to use knowledge from the

of wh-question as follows: Who? (person), to answer "Who cooked dinner?" If th

Where? (place), What? (thing), and What do- dent responded "mom," his respons

ing? (event). Reading materials were selected scored correct. If the student respo

from the students' current level in a Direct "Nancy," it was scored incorrect and m

Instruction reading program and was between indicate that the student did not compreh

two to four pages in length. During each in- the passage and answered based on the

tervention and probe session, students read mation found on the graphic organizer

from the next story, ensuring that they never If the student responded "kitchen," it w

encountered the same story twice. Targeted counted incorrect and might indicate t

text was changed for each session and probe did not comprehend the type of ques

to prevent students from memorizing re- asked. Aaron and Mark answered the q

sponses. tions vocally. Joe answered vocally, but also

pointed to the written word on the grap

Data Collection

organizer. Responses were recorded as corr

or incorrect, and the number of independ

Dependent variables. Data were collected on correct responses was gr

two dependent variables. First, data were col- interval graph (see Figur

lected on the accuracy of sorting words (pre- Interobserver reliability

sented as text) into the graphic organizer cor- ability was conducted by co

responding to the type of wh-question. In ond observer's scores with

these probes, occurring after reading the pas- scores. Reliability sessions w

sage but prior to answering wh-questions, stu- uted across baseline, interv

dents were shown a list of words by the re- tenance phases for all student

searcher and were asked to sort (i.e., write) reliability was scored item

each word into the corresponding category. Heron, & Heward, 2007)

For example, when presented with the word dividing the total disagree

"mom," the response was scored correct if the opportunities and mult

Graphic Organizers / 239

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BL GO

BL GO Maintenance

Maintenance disagree and five representing strongly agree.

8 " O

o 0 0

The experimenter read five questions to stu

o o

dents and they reponded by circling the word

6■

(paired with a symbol) yes or no.

4 *

" o ÍV\>

2■

0 -

V Experimental Design

Aaron

This study used a delaye

across participants desig

q. 88 cited in Cooper et al., 200

nT

\T

1/1

cd b6 designs are a common re

t3 44 ■

cu

gle-subject research and

o 2 " with special needs popula

u

sample of participants is

Mark

Mark

et al., 2007; Kennedy, 20

<D

-Q

1984). There was a basel

E

by an intervention phas

o

0 nance phase. The second

o duced to the intervention once the first stu

\/y~

Yw

dent's data path showed a change in level

and/or trend. The third student was intro

duced to the intervention in the same manner

Joe

once the second student's data path demon

strated a change in level and/or trend. The

10 15 20 25 30

intervention ended once the student correctly

Sessions answered at least seven out of eight compre

Sessions

hension questions about a text in three con

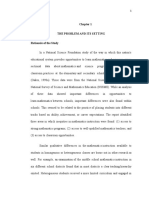

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Number

Numberof

ofcorrect

correct responses

responses on on

wh-wh

secutive sessions and at least five data points

questions

questionsfor Aaron,

for Mark,

Aaron, and Joe

Mark, and Joe per phase were established.

(open data points). Solid, horizontal

lines show mean correct words sorted

in graphic

in graphicorganizers.

organizers.BLBL = Baseline, Procedure

= Baseline,

GO = Graphic Organizers.

Baseline. Data were collected during each

baseline session by asking the student to corn

Aaron, interobserver reliability was conducted plete two types of probes: (a) sor

in 31.25% of total sessions and averaged words into corresponding wh-question

97.5% (range = 87.5%-100%). For Mark, in- ries on a graphic organizer (two of

terobserver reliability was also conducted in of wh-question), and (b) answering

31.25% of total sessions and averaged 97.5% questions about a text (two of each t

(range = 87.5%-100%). For Joe, interob- question). The experimenter did not

server reliability was conducted in 33.33% of corrective feedback on students'

total sessions and averaged 100%. during probes. Once a minimum of five data

Social validity. Social validity question- points and a stable or decreasing trend was

naires can obtain stakeholders' (e.g., partici- established, the first student began the inter

pants, teachers, parents) opinions about an vention phase. Baseline probes were con

intervention's goals, outcomes, and methods ducted daily following completion of the read

(Cooper et al., 2007). After the maintenance ing passage. Reading passages were changed

phase of the study the students and their class- for each probe to ensure students were unable

room teachers completed questions that ad- to memorize responses. Each probe was con

dressed social validity. The teachers' question- ducted in the classroom during typical instruc

naire included six items ranked on a Likert tional time and lasted approximately 10 min.

scale with possible scores ranging from one Graphic organizer. The intervention using

through five with one representing strongly the graphic organizer was conducted in the

240 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-June 2013

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

same manner as the baseline sessions with the curacy of implementation of the intervention,

exception of the introduction of prompting to The second observer watched sessions and

teach the students to use the graphic orga- completed a procedural reliability checklist,

nizer correctly. The experimenter used a least Procedural reliability was evenly distributed

to most prompting hierarchy (independent, across baseline, intervention, and mainte

verbal, gesture, and physical) to teach each nance sessions. Reliability was conducted in

student to sort words into corresponding cat- 31.25% of Aaron and Mark's sessions and av

egories on a graphic organizer and answer eraged 100%. Procedural reliability was con

corresponding comprehension questions from ducted in 33.33% of Joe's sessions and aver

a short passage. For example, the experimenter aged 100%.

presented the graphic organizer and a list

of eight words (two from each category). The Results

experimenter asked the student to write (i.e.,

sort) the words into the corresponding cate- Figure 1 shows the number of independent

gories, providing least to most prompting as correct responses to the wh-questions for

needed. After the words were successfully Aaron, Mark, and Joe. The x-axis represents

sorted, the experimenter presented a short probes and the y-axis represents the number

reading passage (passages were never re- of independent correct responses during each

peated), the student read it aloud, and then probe. The solid, horizontal lines indicate the

the experimenter presented eight corre- mean of words sorted correctly in the graphic

sponding wh-questions about the text, and organizer per phase. All three participants

prompted the student to use his graphic orga- demonstrated an immediate change in level

nizer. As described previously, the eight ques- after instruction on the graphic organizer be

tions included two questions from each cate- gan, and quickly met the criteria to move to

gory: who, what, where, and what doing. This maintenance.

was to ensure that students had to respond During baseline, Aaron's performance aver

according to the type of information re- aged 3.8 correct answers on comprehension

quested and ensure that the response was cor- probes. The data were low and somewhat vari

rect according to the passage. Students were able. During baseline Aaron averaged 4.8 in

able to look back at the text or graphic orga- dependent correct words sorted in the

nizer at any point. graphic organizer. During the intervention

Generalization and maintenance. Generaliza- phase Aaron averaged 7.2 correct answer

tion data were taken once in baseline and wh-questions. The data in this phase w

once in maintenance by scoring permanent high and stable. During the interve

products from each student's responses to phase Aaron 7.8 independent correct

questions from their reading in their special sorted in the graphic organizer. During m

education classrooms. The students partid- tenance Aaron averaged 7.6 independe

pated in a leveled Direct Instruction reading rect answers to wh-questions per pro

program that contained reading comprehen- data in this phase remained high and

sion worksheets. The examiner scored the stu- During maintenance Aaron average

dents' responses to literal wh-questions on dependent correct words sorted ont

these worksheets that were completed with graphic organizer.

their regular teachers during reading instruc- During baseline, Mark's performan

tion. The students did not use the graphic aged 2.7 correct answers to wh-questio

organizers during their teachers' reading in- probe. The data were low and showe

struction. Maintenance data were collected variability. During baseline Mark avera

once per week after the student completed independent correct words sorted i

the intervention phase. Aaron had five weeks graphic organizer. During the interv

of maintenance data, Mark had four weeks of phase Mark averaged 6.4 correct ans

maintenance data, and Joe had three weeks of wh-questions per probe. Mark's data

maintenance data. phase were high, stable, and showed an in

Procedural reliability. Procedural reliability creasing trend. During the interventi

served as the primary method of assessing ac- Mark averaged 7.0 independent corre

Graphic Organizers / 241

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

sorted in the graphic organizer. During main- an appropriate way to help teach wh-questions

tenance Mark averaged 7.25 correct answers about a text, (c) the student has answered

to wh-questions per probe. His data in this wh-questions in the classroom, and (d) the

phase remained high and stable. During student increased his ability to answer wh

maintenance Mark averaged 7.5 independent questions from reading in general. Finally,

correct words sorted onto the graphic orga- teachers had some disagreement on whether

nizer. the student had been able to accurately an

Joe's performance in baseline averaged 3.6 swer reading

correct answers to wh-questions per probe. ing regular En

The data were low with a fair amount of vari- homework. One teacher rated this as a 2,

ability. During baseline Joe averaged 5.6 inde- another as a 4, and the last as a 5. Teachers

pendent correct words sorted in the graphic also had the opportunity to make open ended

organizer. During the intervention phase Joe comments. Two teachers responded, "The

averaged 6.1 independent correct answers to graphic organizer has been very helpful to my

wh-questions per probe. His data in this phase student in making progress on reading corn

were higher than the baseline phase, but ini- prehension. The hands-on visual approach is

daily demonstrated some variability before great," and "Using the graphic organizer

stabilizing. During the intervention phase helped clarify the important information from

Joe averaged 7.4 independent correct words extraneous information."

sorted in the graphic organizer. During main- Students all responded "yes" to the follow

tenance Joe averaged 7.0 correct answers to ing questions: (a) "Did the graphic organizer

wh-questions per probe. Joe's data in this help you learn about the types of wh-ques

phase remained high with a small amount of tions?," (b) "Do you read a lot during your

variability. During maintenance Joe averaged day?," and (c) "Did you like learning this way?"

7.3 independent correct words sorted in the Two of the three students reponded "yes" to

graphic organizer. the following two questions: (a) "Did you like

the lessons?," and (b) "Did the graphic orga

.o ,. .. nizers help you answer questions about what

Generalization ....

you read?"

Data were collected in the form of percent of

wh-questions answered correctly fromDiscussion

stu

dents' reading instruction from their special

education teachers. All three students' scores The purpose of this study was to exami

improved from baseline to generalization. effects of wh-question graphic organ

Aaron's baseline score was 0%, and improved reading comprehension skills in student

to 100% during the generalization probe that ASD. A functional relationship was

was conducted during the maintenance phase. tween the use of graphic organizer

Mark's baseline score was 33%, and improved students' correct responses to literal wh

to 75% during the generalization probe that tions from short passages. The stud

was conducted during the maintenance phase. formance also demonstrated a high

Joe's baseline score was 40%, and improved maintenance, and they were able t

to 100% during the generalization probe that wh-questions from three to five weeks

was conducted during the maintenance phase. stopping the intervention. Additio

three students were able to demonstrate gen

eralization to their reading program work

Social Validity

sheets administered during regular reading

Teachers reported that they strongly agreed instruction.

that reading comprehension is useful in the Graphic organizers have been use

student's daily life. The teachers rated the fully to teach reading comprehension

following questions as either a 4 or 5 on a a wide range of students such as youn

5-point scale: (a) they agreed that graphic and second language students (Cami

organizers helped the student answer compre- 2010; Jiang & Grabe, 2007). Addi

hension questions, (b) graphic organizers are graphic organizers and visual suppo

242 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-June 2013

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

been recommended to teach reading compre four-column wh-question graphic organizer

hension skills to students with ASD as a way to (available from the corresponding author)

utilize visually cued instruction (Gately, 2008). used in the study was low cost and easy to

This study demonstrates that use of graphic make on a word processor, making it easy

organizers can help students with ASD im for teachers to supplement their reading in

prove their ability to answer literal wh-ques struction. Social validity findings from teach

tions about a text. However, this study focused ers were generally positive, suggesting that

on students with ASD who met a narrow set of graphic organizers might be a strategy they

criteria and the extent to which graphic orga would use when teaching reading comprehen

nizers can help other students with ASD im sion to students with ASD.

prove reading comprehension is unclear. This

study focused on students with ASD who were References

vocal, able to communicate basic wants and

needs, able to read aloud, but had difficulty Bursuck, W. D., & Damer, M. (2011). Reading in

with reading comprehension. Specifically, struction for students who are at risk or have disabilities

(2nded.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

they lacked skills at answering literal compre

hension questions. Therefore, the extent to Camine, D. W., Silbert, J., Kame'enui, E. J., &

Tarver, S. G. (2010). Direct instruction reading (5th

which a graphic organizer could help students

ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

with ASD answer inferential comprehension

Chiang, H., & Lin, Y. (2007). Reading comprehen

questions is not clear. sion instruction for students with autism spec

trum disorders: A review of the literature. Focus

Limitations and Future Research on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 22,

259-267.

This study was the first to use graphic organiz Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L.

ers to teach reading comprehension skills to (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Upper

students with ASD. Additional replications of Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Flores, M. M., & Ganz,J. B., (2007). Effectiveness of

this study with a variety of participants, set

direct instruction for teaching statement infer

tings, and researchers are required in order

ence, use of facts, and analogies to students with

for the use of graphic organizers to teach developmental disabilities and reading delays. Fo

reading comprehension, specifically answer cus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities,

ing literal wh-questions, to become an estab 22, 244-251.

lished intervention.

Gately, S. E. (2008). Facilitating reading compre

A second limitation of this study is the hension for students on the autism spectrum.

experimenter's role as primary instructor TEACHING Exceptional Children, 40(3), 40-45.

throughout implementation of the study. Heward, W. L. (1978, May). The delayed multiple base

Classroom teachers were not asked to admin line design. Paper presented at the Fourth Annual

Convention of the Association for Behavior Anal

ister the intervention. This limits the authors'

ysis, Chicago.

ability to predict whether teacher implemen

Hundert, J., & van Delft, S. (2009). Teaching chil

tation would maintain high treatment fidelity.

dren with autism spectrum disorders to answer

Future studies could use classroom teachers to

inferential "why" questions. Focus on Autism and

deliver the graphic organizer intervention. Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 67-76.

A third limitation was that instruction was

Jiang, X., & Grabe, W. (2007). Graphic organizers in

delivered during one-to-one sessions. Since reading instruction: Research findings and issues.

group instruction is commonly used in class Reading in a Foreign Language, 19, 34-55.

rooms, future research could evaluate instrucKennedy, C. H. (2005). Single-case designs for educa

tion with graphic organizers during small ortional research. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Nation, K-, Clarke, P., Wright, B., & Williams, C.

whole group instruction.

(2006). Patterns of reading ability in children

with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism

Implications for Practice and Developmental Disorders, 36, 911-919. doi:

10.1007/sl0803-006-0130-l

Results of this study suggest that graphic orga

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to

nizers might help students with ASD improve read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific re

their literal reading comprehension. Thesearch literature on reading and its implications for

Graphic Organizers / 243

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

reading instruction. Washington, DC: National In egy instruction on high-functioning adolescents

stitute of Child Health and Human Development. with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism

Newman, T. M., Macomber, D., Naples, A. J., Babitz, and Other Developmental Disabilities, 23, 217-228.

T„ Volkmar, F., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2007). Hy doi: 10.1177/1088357608324714

perlexia in children with autism spectrum disor Tawney, J. W., & Gast, D. L. (1984). Single subject

ders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, research in special education. Columbus, OH: Mer

37, 760-774. doi: 10.1007/sl0803-006-0206-y rill.

Reynhout, G., & Carter, M. (2008). A pilot study to Wahlberg, T., & Magliano, J. P. (2004). The ability

determine the efficacy of a social story interven

of high function individuals with autism to com

tion for a child with autistic disorder, intellectual

prehend written discourse. Discourse Processes, 38,

disability and limited language skills. Australasian 119-144.

Journal of Special Education, 32, 161-175. doi:

Watkins, C. L., & Slocum, T. A. (2004). The com

10.1080/10300110802047210

ponents of Direct Instruction. In N. Marchand

Saalasti, S., Lepisto, T., Toppila, E., Kujala, T.,

Martella, T. Slocum, & R. Martella (Eds.), Intro

Laakso, M., Nieminin-von Wendt, T Jansson

duction to direct instruction (pp. 75-110). Boston:

Verkasalo, E. (2008). Language abilities of chil

dren with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism

Allyn & Bacon.

and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1574-1580. doi:

10.1007/sl 0803-008-0540-3 Received: 9 February 2012

Songlee, D., Miller, S. P., Tincani, M., Sileo, N. M., Initial Acceptance: 5 April 2012

Perkins, P. G. (2008). Effects of test-taking strat Final Acceptance: 10 June 2012

244 / Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities-June 2013

This content downloaded from

129.237.35.237 on Sat, 07 Aug 2021 13:14:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Division On Autism and Developmental Disabilities Education and Training in Autism and Developmental DisabilitiesDocument14 pagesDivision On Autism and Developmental Disabilities Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilitiesapi-315856815No ratings yet

- 1045988x 2012 PDF UdlDocument10 pages1045988x 2012 PDF Udlapi-256799877No ratings yet

- 2bec PDFDocument12 pages2bec PDFchenee liezl horarioNo ratings yet

- Training Peers To Teach Reading Comprehension To StudentsDocument17 pagesTraining Peers To Teach Reading Comprehension To StudentsIngrid DíazNo ratings yet

- IncreaseDocument12 pagesIncreaseapi-260700588No ratings yet

- Classroom ParticipationDocument16 pagesClassroom ParticipationmhabranNo ratings yet

- Improving Students Sense of Argumentation Using Claim Evidence and Reasoning Approach Chapter 1 5. GROUP 3.Document50 pagesImproving Students Sense of Argumentation Using Claim Evidence and Reasoning Approach Chapter 1 5. GROUP 3.John Cobe AdoveNo ratings yet

- Do Targeted Fluency Interventions Positively Impact ComprehensionDocument35 pagesDo Targeted Fluency Interventions Positively Impact ComprehensionValeska ArandaNo ratings yet

- Action Research ProposalDocument18 pagesAction Research Proposalborgek11100% (5)

- Annotated BibliographyDocument2 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-555899952No ratings yet

- Literature Review On Reading DisabilityDocument11 pagesLiterature Review On Reading Disabilityc5hc4kgx100% (1)

- Effective Reading Remediation Instructional Strate PDFDocument6 pagesEffective Reading Remediation Instructional Strate PDFCarlo LegaspinaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Coaching Behaviour Modification Practices On Reinforcement of Reading Abilities Among Dyslexic Learners in KenyaDocument5 pagesInfluence of Coaching Behaviour Modification Practices On Reinforcement of Reading Abilities Among Dyslexic Learners in KenyaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Close Reading As An Intervention For Struggling Middle School ReadersDocument12 pagesClose Reading As An Intervention For Struggling Middle School ReadersNurilMardatilaNo ratings yet

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsFrom EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsNo ratings yet

- Effect of Proxemics On Academic Achievement of Learning Disabled Students in Inclusive ClassroomDocument9 pagesEffect of Proxemics On Academic Achievement of Learning Disabled Students in Inclusive ClassroomAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- ED619622Document31 pagesED619622John RambooNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument8 pagesReview of Related LiteratureNORZEN LAGURANo ratings yet

- Influence of Mathematical Dyslexia Condition On Academic Performance in Upper Primary Learners in Kenyan Public SchoolsDocument6 pagesInfluence of Mathematical Dyslexia Condition On Academic Performance in Upper Primary Learners in Kenyan Public SchoolsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Reciprocal TeachingDocument36 pagesThe Impact of Reciprocal Teachingborgek11100% (2)

- Action ResearchDocument23 pagesAction ResearchDANIEL DUAVENo ratings yet

- Yurpo Pamela PRE ORALDocument24 pagesYurpo Pamela PRE ORALmilagroszamora221967No ratings yet

- Morphology Pilot StudyDocument16 pagesMorphology Pilot Studyapi-456699912No ratings yet

- Bcvs Project Title: Multiple Intelligences and Learning StylesDocument17 pagesBcvs Project Title: Multiple Intelligences and Learning StylesasarvigaNo ratings yet

- Oral Reading Fluency and ComprehensionDocument7 pagesOral Reading Fluency and ComprehensionGracy LiteralNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Systematic Instruction in A Group Format To Teach Science To Students With Autism and Intellectual DisabilityDocument18 pagesThe Effects of Systematic Instruction in A Group Format To Teach Science To Students With Autism and Intellectual DisabilityjoannadepaoliNo ratings yet

- Effects of Multimedia Vocabulary Instruction On Adolescents With Learning DisabilitiesDocument23 pagesEffects of Multimedia Vocabulary Instruction On Adolescents With Learning DisabilitiesGabriela Mosqueda CisternaNo ratings yet

- The Alternative Learning System (ALS) Students' Challenges in Untangling The Reading Comprehension AbilityDocument9 pagesThe Alternative Learning System (ALS) Students' Challenges in Untangling The Reading Comprehension AbilityPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- PUBLISHABLEDocument14 pagesPUBLISHABLEKIMBERLY AMODIANo ratings yet

- Evidence 1Document10 pagesEvidence 1api-662101203No ratings yet

- 1462-Texto Del Artículo-4508-1-10-20171120Document18 pages1462-Texto Del Artículo-4508-1-10-20171120Zamzam DiamelNo ratings yet

- Visual Supports For Students With Disabilities Alicia Hembree and Kimberly GrahamDocument6 pagesVisual Supports For Students With Disabilities Alicia Hembree and Kimberly GrahamAHembreeNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of The Value of Problem-Based Learning Among StudentsDocument19 pagesPerceptions of The Value of Problem-Based Learning Among StudentsTerim ErdemlierNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Digital Storytelling As An Assessment Tool 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: Digital Storytelling As An Assessment Tool 1vifongiNo ratings yet

- Read 650 - Symposium Conference Proposal 3Document7 pagesRead 650 - Symposium Conference Proposal 3api-740242908No ratings yet

- An Exploration of Teacher's Experiences Towards Managing Challenging Behaviour Exhibited by Learners With DyslexiaDocument10 pagesAn Exploration of Teacher's Experiences Towards Managing Challenging Behaviour Exhibited by Learners With DyslexiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Journal of Literacy Research 1983 McKeown 3 18Document17 pagesJournal of Literacy Research 1983 McKeown 3 18Nenk YuliNo ratings yet

- Improving Listening Comprehension Responses For Students With Moderate Intellectual Disability During Literacy ClassDocument20 pagesImproving Listening Comprehension Responses For Students With Moderate Intellectual Disability During Literacy Classapi-255533609No ratings yet

- Working Thesis - Parenthetical DocumentationDocument52 pagesWorking Thesis - Parenthetical DocumentationDea Ann Sto. DomingoNo ratings yet

- Alexander and WoodcraftDocument8 pagesAlexander and WoodcraftGenesis Dalapo AbaldeNo ratings yet

- Digital MediaDocument20 pagesDigital MediamaprevisNo ratings yet

- Research On Impact of Socio Demographics Attributes On Learners Success in MathDocument32 pagesResearch On Impact of Socio Demographics Attributes On Learners Success in MathWinnie Rose GonzalesNo ratings yet

- The Truth About Homework from the Students' PerspectiveFrom EverandThe Truth About Homework from the Students' PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its Setting Rationale of The StudyDocument39 pagesThe Problem and Its Setting Rationale of The StudyGab TangaranNo ratings yet

- VOCAB Research UpdatedDocument46 pagesVOCAB Research Updatedjambyvillarsadsad123No ratings yet

- Grace Case StudyDocument6 pagesGrace Case Studyapi-427522957No ratings yet

- The ProblemDocument26 pagesThe ProblemCarlito AglipayNo ratings yet

- Project Muse 614737Document33 pagesProject Muse 614737Paul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Reading Instruction For Students With Intellectual DisabilitiesDocument22 pagesComprehensive Reading Instruction For Students With Intellectual DisabilitiesBlanca Flor Camarillo SalazarNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Multiple Intelligences and Participation Rate in Extracurricular Activities 10956Document7 pagesThe Relationship Between Multiple Intelligences and Participation Rate in Extracurricular Activities 10956Phili-Am I. OcliasaNo ratings yet

- King, Lemons, Davidson, Fulmer y Mrachko 2020Document18 pagesKing, Lemons, Davidson, Fulmer y Mrachko 2020Pedro Alberto Herrera LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Multiple-Intelligence Approach & Traditional Teaching Approach On Educational ESP Attainment and Attitudes of Educational Science StudentsDocument3 pagesImpact of Multiple-Intelligence Approach & Traditional Teaching Approach On Educational ESP Attainment and Attitudes of Educational Science StudentsTI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- Research Group 5 1 3Document12 pagesResearch Group 5 1 3Rikka Marie De LaraNo ratings yet

- Project7 ResearchDocument11 pagesProject7 Researchapi-309801450No ratings yet

- Applying The Think-Aloud Strategy To Improve Reading Comprehension of Science ContentDocument35 pagesApplying The Think-Aloud Strategy To Improve Reading Comprehension of Science ContentBenj AlejoNo ratings yet

- Banda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFDocument7 pagesBanda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFMuhammad Bilal ArshadNo ratings yet

- Response To Intervention: Increasing Fluency, Rate, and Accuracy For Students at Risk For Reading FailureDocument20 pagesResponse To Intervention: Increasing Fluency, Rate, and Accuracy For Students at Risk For Reading FailurePaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Clouse-Bass and Miller Lit Intervention ReportDocument8 pagesClouse-Bass and Miller Lit Intervention Reportapi-741399259No ratings yet

- Retell As An Indicator of Reading Comprehension: Deborah K. ReedDocument32 pagesRetell As An Indicator of Reading Comprehension: Deborah K. Reedkeramatboy88No ratings yet

- Ej 1230072Document5 pagesEj 1230072Abderrahim LidriNo ratings yet

- Contentserver 21Document13 pagesContentserver 21api-550243992No ratings yet

- Strategies For Success Evidence-Based Instructional Practices For Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 2Document1 pageStrategies For Success Evidence-Based Instructional Practices For Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 2api-550243992No ratings yet

- Strategies For Success Implementation 1Document1 pageStrategies For Success Implementation 1api-550243992No ratings yet

- Project Muse 317579Document15 pagesProject Muse 317579api-550243992No ratings yet

- Strategies For Success Evidence Based Instructional Practices For Students With Emotional and Behavioral DisordersDocument9 pagesStrategies For Success Evidence Based Instructional Practices For Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disordersapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Effects of Classroom Practices On Reading Comprehension, Engagement, and Motivations For AdolescentsDocument30 pagesEffects of Classroom Practices On Reading Comprehension, Engagement, and Motivations For Adolescentsapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Project Muse 597970Document33 pagesProject Muse 597970api-550243992No ratings yet

- Retrieval Practice Implementation 1Document1 pageRetrieval Practice Implementation 1api-550243992No ratings yet

- Contentserver 20Document20 pagesContentserver 20api-550243992No ratings yet

- Contentserver 19Document17 pagesContentserver 19api-550243992No ratings yet

- Retrieval-Based Learning: Active Retrieval Promotes Meaningful LearningDocument7 pagesRetrieval-Based Learning: Active Retrieval Promotes Meaningful Learningapi-550243992No ratings yet

- The Effect of Retrieval Practice in Primary School Vocabulary Learning Notes 3Document1 pageThe Effect of Retrieval Practice in Primary School Vocabulary Learning Notes 3api-550243992No ratings yet

- Contentserver 18Document9 pagesContentserver 18api-550243992No ratings yet

- Contentserver 17Document16 pagesContentserver 17api-550243992No ratings yet

- Goal Setting and Self-Monitoring For Students With DisabilitiesDocument7 pagesGoal Setting and Self-Monitoring For Students With Disabilitiesapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Journal of Experimental Child Psychology: Emily R. Fyfe, Bethany Rittle-JohnsonDocument12 pagesJournal of Experimental Child Psychology: Emily R. Fyfe, Bethany Rittle-Johnsonapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Goal Setting Notes 1Document1 pageGoal Setting Notes 1api-550243992No ratings yet

- Graphic Organizers and Students With Learning Disabilities A Meta-Analysis Notes 2Document1 pageGraphic Organizers and Students With Learning Disabilities A Meta-Analysis Notes 2api-550243992No ratings yet

- Goal ImplementationDocument1 pageGoal Implementationapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Graphic Organizers and Students With Learning Disabilities: A Meta-AnalysisDocument22 pagesGraphic Organizers and Students With Learning Disabilities: A Meta-Analysisapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Graphic Organizers and Their Effects On The Reading Comprehension of Students With LDDocument14 pagesGraphic Organizers and Their Effects On The Reading Comprehension of Students With LDapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Graphic Organizer Implementation 1Document1 pageGraphic Organizer Implementation 1api-550243992No ratings yet

- Immediate Feedback Notes 2Document1 pageImmediate Feedback Notes 2api-550243992No ratings yet

- Feedback 2Document21 pagesFeedback 2api-550243992No ratings yet

- Using Immediate Feedback To in 1Document10 pagesUsing Immediate Feedback To in 1api-550243992No ratings yet

- Immediate Feedback Implementation 1Document1 pageImmediate Feedback Implementation 1api-550243992No ratings yet

- Cra Implementation 1Document1 pageCra Implementation 1api-550243992No ratings yet

- Ebp CraDocument11 pagesEbp Craapi-550243992No ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practices Applications of Concrete Representational Abstract Framework Across Math Concepts For Students With Mathematics Disabilities Notes 3Document1 pageEvidence-Based Practices Applications of Concrete Representational Abstract Framework Across Math Concepts For Students With Mathematics Disabilities Notes 3api-550243992No ratings yet

- Samantha Loveless ResumeDocument2 pagesSamantha Loveless Resumeapi-241563761No ratings yet

- English Teacher Resume 1Document3 pagesEnglish Teacher Resume 1literaturemks100% (1)

- Challenges Faced by Visually Impaired Students at Makerere and Kyambogo UniversitiesDocument12 pagesChallenges Faced by Visually Impaired Students at Makerere and Kyambogo UniversitiesDesire ramsNo ratings yet

- Bi Ling SampleDocument12 pagesBi Ling Sampleirish xNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Successful Culinary Lab Management GuidelinesDocument12 pagesLesson Plan Successful Culinary Lab Management GuidelinesmaitebaNo ratings yet

- Abbeydale Grange School - Prospectus 2008/09Document20 pagesAbbeydale Grange School - Prospectus 2008/09abbeydalegrange100% (7)

- Challenges To Preparing Teachers To Instruct All Stu - 2023 - Teaching and TeachDocument10 pagesChallenges To Preparing Teachers To Instruct All Stu - 2023 - Teaching and TeachjbagNo ratings yet

- Zaretsky PracticeTheoryInclusive 2005Document23 pagesZaretsky PracticeTheoryInclusive 2005sofcraftNo ratings yet

- Karyotyping Virtual Lab PlusDocument3 pagesKaryotyping Virtual Lab PlusVictoria YeeNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document5 pagesCase Study 2api-247285537100% (1)

- Teghan Knepper ResumeDocument2 pagesTeghan Knepper Resumeapi-547258912No ratings yet

- Savant SyndromeDocument10 pagesSavant Syndromepk_skbbNo ratings yet

- Clinical-Practice-Evaluation-1-Self-Evaluation 1 1Document3 pagesClinical-Practice-Evaluation-1-Self-Evaluation 1 1api-690519698100% (1)

- Overview of KSPKDocument38 pagesOverview of KSPKBukan Puteri Lindungan Bulan75% (12)

- Adapt IfDocument157 pagesAdapt IfCahyoNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument1 pageDaftar PustakaRizka Cii Putri TaufiqNo ratings yet

- Early Reading Intervention Program: Ms. Precious Angela Roma BalDocument10 pagesEarly Reading Intervention Program: Ms. Precious Angela Roma BalPrecious Angela BalNo ratings yet

- III Semister Syllbus B.ed 2016 17 KarnatakaDocument56 pagesIII Semister Syllbus B.ed 2016 17 KarnatakaMuhammad Rafiuddin100% (1)

- AWS Exam Cancellation Refund Policies and Other FeesDocument1 pageAWS Exam Cancellation Refund Policies and Other FeesZeeshan HasanNo ratings yet

- Sam Iep 1Document10 pagesSam Iep 1api-260964883100% (1)

- Landmark Academy COVID-19 Preparedness & ResponsePlanDocument29 pagesLandmark Academy COVID-19 Preparedness & ResponsePlanTheTimesHeraldNo ratings yet

- Thesis About Special Education in The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesThesis About Special Education in The PhilippinesHelpWithCollegePaperWritingCanada100% (2)

- Lier Upper Secondary SchoolDocument8 pagesLier Upper Secondary SchoolIES Río CabeNo ratings yet

- Upper Secondary School: Japan Exchange and Teaching ProgramDocument5 pagesUpper Secondary School: Japan Exchange and Teaching ProgramTasleem KhâñNo ratings yet

- Resume - Kimberly Grigg 1Document2 pagesResume - Kimberly Grigg 1api-267104542No ratings yet

- A Smile As Big As The MoonDocument3 pagesA Smile As Big As The Moonanalyn bonzoNo ratings yet

- Pes P6 TGDocument216 pagesPes P6 TGAnonymous xgTF5pfNo ratings yet

- sp0009 - Functional Assessment PDFDocument4 pagessp0009 - Functional Assessment PDFMarlon ParohinogNo ratings yet

- Pillars of Strength: Meeting The Demands of Learners With Special Educational Needs (LSENs) in Surigao City National High SchoolDocument33 pagesPillars of Strength: Meeting The Demands of Learners With Special Educational Needs (LSENs) in Surigao City National High Schoolvinay kumarNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Unit 2Document2 pagesPortfolio Unit 2Chi Raymond TumanjongNo ratings yet