Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Catrin Rutland

Uploaded by

Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Catrin Rutland

Uploaded by

Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànCopyright:

Available Formats

DEVELOPING THE STUDENT PROFESSIONAL

How Does Student Educational

Background Affect Transition into

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

the First Year of Veterinary School?

Academic Performance and Support

Needs in University Education

Catrin S. Rutland n Heidi Dobbs n Sabine Tötemeyer

ABSTRACT

The first year of university is critical in shaping persistence decisions (whether students continue with and

complete their degrees) and plays a formative role in influencing student attitudes and approaches to learning.

Previous educational experiences, especially previous university education, shape the students’ ability to adapt to

the university environment and the study approaches they require to perform well in highly demanding profes-

sional programs such as medicine and veterinary medicine. The aim of this research was to explore the support

mechanisms, academic achievements, and perception of students with different educational backgrounds in their

first year of veterinary school. Using questionnaire data and examination grades, the effects upon perceptions,

needs, and educational attainment in first-year students with and without prior university experience were

analyzed to enable an in-depth understanding of their needs. Our findings show that school leavers (successfully

completed secondary education, but no prior university experience) were outperformed in early exams by those

who had previously graduated from university (even from unrelated degrees). Large variations in student percep-

tions and support needs were discovered between the two groups: graduate students perceived the difficulty and

workload as less challenging and valued financial and IT support. Each student is an individual, but ensuring that

universities understand their students and provide both academic and non-academic support is essential. This

research explores the needs of veterinary students and offers insights into continued provision of support and

improvements that can be made to help students achieve their potential and allow informed ‘‘Best Practice.’’

Key words: veterinary students, assessment, student support, transition to university, graduate students,

school leavers

INTRODUCTION able, motivated, and committed but also highly competi-

The first year of university has been identified as the tive and accustomed to academic success. Degree com-

most critical in shaping persistence decisions (whether pletion rates in UK universities are generally high in

students continue with and complete their degrees) and medicine and veterinary medicine with attrition rates

it plays a formative role in influencing student attitudes only around 5%. In contrast, the overall university attri-

and approaches to learning.1–5 Similar to medical students,6 tion rate is around 17%. The reasons for leaving are

veterinary students have added pressures compared to usually cumulative and include inappropriate informa-

students in many other programs. Contributing to this tion to make program choice, poor transition to higher

are the course content and high workload; the wide education, unclear academic expectations and lack of

range of skills required; the expectation that one will guidance, insufficient access to support, alienation and

behave like a professional and be judged accordingly; isolation, too many other commitments, and financial

the wide range of people with whom one must commu- pressure.7

nicate effectively; and the emotions associated with diffi- There are mixed views in the literature as to whether

cult situations including life/death decisions. The student more mature students achieve better or worse grades

groups associated with 5-year degree programs such as than younger students. ‘‘Mature’’ is too broad an age

veterinary medicine, which have extensive entry criteria spectrum, since two peak ages were observed in aca-

and work experience requirements, are generally highly demic achievement: 18–19 years old and 26–30 years

372 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1

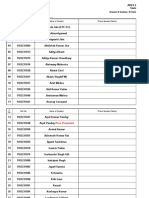

Table 1: Background education status of students applying to veterinary medicine through to the final cohort

School leaver Graduate

Applicants to Veterinary Medicine (n ¼ 1,366) 1,211 (89%) 155 (11%)

Offers made by the university to study veterinary medicine (n ¼ 133) 123 (92%) 10 (8%)

Admitted via gateway program and preliminary program (n ¼ 21) 5 (24%) 16 (76%)

Number of offers accepted (n ¼ 111 *) 85 (77%) 26 (23%)

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

Final cohort (n ¼ 109) 83 (76%) 26 (24%)

* Two school leavers deferred entry for 1 year

old.8 This was confirmed in the statistics for British veter- academic staff member. The numbers of prospective stu-

inary science degrees in 1995: 100% of students under 21 dents at each stage are shown in Table 1.

received a ‘‘good’’ degree (first-class honors or second- Student performance—In the first year of the program,

class honors, upper division), but this figure dropped to students performed summative assessments in all modules

76.6% in the 21–25 age group and increased again to within a systems-based teaching curriculum. Teaching

100% in the 26–30 year old group.9 Figures were not consisted of four block modules (Musculoskeletal [MSK],

available for veterinary medicine, however medicine and Lymphoreticular Cell Biology [LCB], Cardiorespiratory

dentistry showed that numbers attaining a ‘‘good’’ de- [CRS], Neuroscience [NEU]) and two long modules (Ani-

gree decreased with age: 89.5% for the under 21s, 88.4% mal Health and Welfare [AHW] and Personal and Pro-

in the 21–25 group, 63.6% for the 26–30 group, and fessional skills [PPS]). Except for PPS, all modules were

66.7% for those aged 31–40.9 In contrast, other general assessed online by multiple- and extended-choice ques-

studies have suggested an increase in attainment until tions (66%), short-answer examinations (spot tests, 33%),

36–40 years of age, with a decline thereafter.10 In the and assessment of practical skills through objective struc-

medical field, very few studies have compared the aca- tured practical examinations (OSPE, pass/fail). PPS was

demic performance of graduate students and school leavers assessed through coursework (100%), a portfolio (pass/

(defined as those who successfully completed secondary fail), and a skills diary (pass/fail). There were two assess-

and further education, but who had no prior university ment points: the first two modules, MSK and LCB, were

experience) in the same curriculum. Most studies focus assessed in January in the first week of the academic term,

on the accelerated graduate entry programs (GEP) in and the other modules, as well as all OSPEs, were

comparison to the traditional medical degree program, assessed at the end of the academic year (June). Prior to

where program type and admission selection rather than the summative assessments, students had the opportunity

graduate student attributes may explain differences.11–13 to participate in formative assessments covering all assess-

Staff often feel that graduate students may need less ment methodologies used.

assistance or guidance as they have already experienced Examination results were analyzed and the performance

the transition to university.8–10 However, the workload of graduate students was compared to the performance

and structure of medical or veterinary degree programs of school leavers: (1) overall year 1, (2) each module, (3)

might constitute a very different and still very challeng- computer-based assessment and spot test for all modules

ing experience, especially if students must work part- (except PPS), (4) number of re-sits (retaking an examina-

time to finance the program. Therefore it is important to tion after a failure), and (5) number of students who

understand the perceptions and needs of students with failed to progress after a re-sit. Admission into the uni-

degrees and also to understand whether they achieve versity was via one of three routes: preliminary year,

the same grades as school/college leavers. The aim of straight into first year, or ‘‘gateway’’ year. The university

this study is to investigate the impact of prior education ‘‘preliminary year’’ in veterinary studies required AAB

on students’ academic performance, perception of the first grades from any A-level subjects but was specifically for

year of the veterinary medicine and science program, and students who did not take A-level biology or chemistry.

support requirements. Students accepted into the first year had achieved A-level

grades including A for biology, A for chemistry, and at

MATERIALS AND METHODS least B in any other subject excluding general studies.

Student cohort—The student cohort in the 5-year BVMBVS The ‘‘gateway’’ further education college program required

with integrated BVMedSci at The University of Nottingham grades B, B, and C at A level and students were taught

consisted of 109 students. To gain entrance into the veter- in a different location from the veterinary school. The

inary school, all students applied through the British ‘‘preliminary year’’ students were taught within the

UCAS system and completed a questionnaire specific higher-education environment of the veterinary school

to this veterinary school. All students were either inter- and were grouped with the graduate students because

viewed in a three-part interview process (interview with they had experience with the university lifestyle and

academic and clinical staff, practical aptitude test, and education system before starting the veterinary degree.

team-working task) or in a telephone interview (for some School leavers were defined as those who had success-

international students) with a basic scientific and clinical fully completed secondary and further education, but had

no prior university experience. A-level grades achievable

doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC 373

Table 2: Student ratings (median) of learning experiences

Educational background

School leaver Graduate

Learning experience statement (n ¼ 76) (n ¼ 26) p

I am learning a lot in my first year at university. 2 (0–100) 2 (0–23)

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

I have felt overwhelmed by the workload this year. 26 (0–100) 32 (0–87)

My lecturers’ teaching has usually been clear and understandable. 25 (0–81) 28.5 (0–50)

The pace at which the material has been covered has been too fast. 42 (0–90) 45 (16–87)

I am less confident than other people to voice my opinion in self-directed 67 (2–100) 61 (23–100)

learning sessions.

I am not confident enough to voice my opinion in lectures/seminars. 50 (0–100) 57.5 (0–100)

I feel confident to participate in all tasks in practical teaching. 11 (0–100) 18.5 (0–100)

For my ability (or level of preparation), the course seemed too difficult. 56 (0–100) 72.5 (41–100) .01

This year has been too stressful. 50 (0–100) 50 (12–100)

The academic requirements have been too demanding. 50 (0–100) 50 (22–100)

I have had relatively little difficulty understanding course material. 50 (2–100) 39.5 (4–71) <.001

The demands on my time and energy have been excessive. 43 (0–100) 42.5 (0–86)

I am satisfied with my progress in learning the knowledge and skills needed for 25 (0–84) 23.5 (0–60)

a veterinary medical degree.

The personal tutor system provides good support. 21 (0–100) 39 (0–66)

My school experience in general prepared me well for my study at university. 43 (0–100) 50 (0–100) .01

My A Levels prepared me well academically for my study this year. 35.5 (0–100) 49 (0–100)

My previous degree prepared me well academically for my study this year. N/A 39 (2–100)

Values indicate median rating (minimum–maximum rating) with options ranging from strongly agree (0) to strongly disagree (100), and with

neutral at 50. Results were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test, two tailed with 95% confidence interval; P values have been given for

statistically significant differences and these are shown in bold font.

are A * –E and unclassified (fail). A unified marking in general/subjects studied/previous degrees, etc.) pre-

scheme is used to compensate for examination paper dif- pared you for this year,’’ ‘‘What could be improved in

ficulty. The maximum points available are 600. A * repre- terms of the support given to students?’’ and ‘‘Please

sents 480 points or above plus over 90% of unified marks give any further comments regarding your experiences

in a set number of examination papers; A is 480 points or this year and the support systems in place.’’ The linear

above; B is 420–479 points; and C is 360–419 points. visual analogue scale responses were measured manually

Questionnaire—A voluntary questionnaire was given by ruler. The support systems that students evaluated are

to all students in the final term of the first year as part of shown in Table 3 and consisted of those offered by the

a PPS teaching session. The Human Subjects Institutional veterinary school, those offered through peer interactions,

Review Board approved the study and the questionnaire. and those offered as general services by the university.

All questions and the student responses are summarized Statistical analysis—Cronbach’s alpha was determined

in Tables 2 and 3. Students were asked (1) to evaluate to measure the internal consistency of the questionnaire,

a number of statements with regards to their first-year and thereby its reliability. Questionnaire responses and

experience (adapted from Powers et al.14 on a linear assessment results of graduates and non-graduates were

visual analogue scale from 0–100 mm, thus ensuring compared using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U

that a continuum is provided rather than discrete jumps) test, two tailed with 95% confidence interval. P values of

from strongly agree to strongly disagree (the neutral mid- less than .05 were deemed significant.

point was marked); (2) to evaluate a range of support

services (peer, veterinary school, and university support) RESULTS

on a linear visual analogue scale (0–100 mm) from very

important to not important at all (the neutral midpoint was Impact of Admission Process on Student

marked); and (3) to complete a number of open questions Cohort

including ‘‘Please add any further comments you have Of the 1,366 applicants to the 5-year BVMBVS with in-

about how well your prior experience of education (school tegrated BVMedSci, 11% (155) were classified as graduates

374 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1

Table 3: Student ratings of support importance

Educational background Whole cohort

School leaver Graduate Not aware of service

Student support (n ¼ 76) (n ¼ 26) p (from n ¼ 103)

School service

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

Personal tutor 20 (0–89) 21 (0–71) 0

Tutor family 39 (0–100) 50 (0–100) 0

Senior tutors 50 (0–100) 34 (0–90) 6

Reception 21 (0–73) 16 (0–58) 0

Welfare officer 28 (0–100) 27 (0–72) 0

Welfare drop-in session 50 (0–100) 50 (0–100) 0

Extramural studies (EMS) placements office 0 (0–50) 0 (0–23) 1

Disability officer 50 (0–100) 49 (0–100) 9

Teaching, learning, and assessments (TLA) office 19.5 (0–100) 15.5 (0–54) 1

Peer support

Other students 5 (0–50) 23 (0–50) 1

Veterinary society (VetSoc) 34 (0–100) 39.5 (0–100) 0

University services

Academic support services 50 (0–100) 32.5 (0–100) 11

Counseling services 50 (0–100) 45.5 (0–100) 10

Financial support service 50 (0–100) 29 (0–56) .04 8

Student-IT helpdesk 32 (0–100) 16.5 (0–100) .04 5

Face-to-face IT support (library) 28.5 (0–100) 24 (0–100) 8

Value represent median (minimum–maximum rating) with options ranging from strongly agree (0) to strongly disagree (100), and with neutral

at 50. Statistical significance (p < .05) was analyzed using Mann–Whitney U test, two tailed with 95% confidence interval, and is indicated in

bold where significant. ‘‘Welfare officer’’ refers to a member of administrative staff who is available to students and can provide non-academic

guidance and advice.

and 89% (1,211) as school leavers. Of the 304 applicants able’’ and that they were ‘‘satisfied with [their] progress

invited to interview, 5% (14) were graduate students. Of in learning the knowledge and skills required for a veter-

the 133 offers made, 8% (10) were to graduate students. inary medicine degree.’’

The final BVMBVS cohort contained 23% (26) graduate School leavers were more likely to feel that the pro-

students from 111 students. In addition to the 10 graduate gram was too hard for their ability (median ¼ 72.5 for

students selected at interview, 16 students were admitted graduates vs. 56 for school leavers, p ¼ .01; medians cal-

from the preliminary program, located at University of culated from a visual analogue scale, 0–100 mm from

Nottingham School of Veterinary Medicine and Science, 0 ¼ strongly agree to 100 ¼ strongly disagree; all ranges are

and were grouped together with the graduate students. shown in corresponding Tables 2 and 3). School leavers

Five students were admitted from the gateway program were less likely to agree that they had relatively little dif-

and were considered to have school/college leaver status. ficulty understanding course material (median ¼ 39.5 for

Two non-graduates deferred entry. These data are also school leavers vs. 50 for graduates, p < .001). Despite the

shown in Table 1. higher number of school leavers finding the work more

difficult, it was clear that school leavers felt that their

Perception of First-Year Experience According school experience had prepared them well for studying

at university in comparison to graduates (median ¼ 39

to Previous Education

for school leavers vs. 21 for graduates, p ¼ .01). There

The return rate for the questionnaires was 94% (103 out

were no comments pertaining to how the students felt

of 109 students), however not all students answered all

that school had prepared them, whether they were think-

questions. The estimated reliability (coefficient alpha) of

ing about academic, personal, organizational, or life skills

a composite score based on all 16 items was .62, which

(Table 2).

is higher than the acceptable values of .5.14,15 The cohort

Free-text answers illustrated that some students felt

responses regarding their first-year experience are sum-

strongly that school had not prepared them for university

marized in Table 2. The whole student cohort strongly

education. Student comments included the following:

agreed that they were ‘‘learning a lot,’’ felt ‘‘confident to

‘‘the sixth form way of teaching is different to university

participate in all tasks in practical teaching,’’ and ‘‘felt

and I don’t feel I was initially prepared by my sixth

overwhelmed by the workload.’’ They also strongly

form,’’ ‘‘school only scratched the surface of most topics

agreed that teaching was ‘‘usually clear and understand-

so I found a huge jump from what I knew to what I was

doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC 375

Table 4: Support systems ranked by importance

Educational background

Student support ranking School leaver ranking Graduate ranking

School service

Personal tutor 4 5

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

Tutor family 10 15

Senior tutors 11 * 11

Reception 5 3

Welfare officer 6 8

Welfare drop-in session 11 * 15

Extramural studies (EMS) placements office 1 1

Disability officer 11 * 14

Teaching, learning, and assessments (TLA) office 3 2

Peer support

Other students 2 6

Veterinary society (VetSoc) 9 12

University services

Academic support services 11 * 10

Counseling services 11 * 13

Financial support service 11 * 9

Student-IT helpdesk 8 4

Face-to-face IT support (library) 7 7

* These categories were ranked equally by the school-leaver group. Ranking data were extrapolated from the rating data given by the

students.

Numbers in bold indicate situations where school leaver and graduate ranking differed by four places or more.

expected to know,’’ ‘‘none of my previous experience Support Mechanisms Based on Previous

prepared me to manage my time effectively in order to Education

cope with the large workload,’’ and ‘‘at school we were The students were asked to rate the importance of avail-

generally spoon fed in the science subjects, which in able support systems, including peer support and the

some cases has been a disadvantage when suddenly being tutor system as well as support systems specific to the

very independent at university.’’ One person stated that veterinary school and the university. All data (median

‘‘subjects studied (biology, maths, chemistry) has given and ranges) are summarized in Table 3. All groups of stu-

me a good ground knowledge which new material has dents (school leaver or graduate) placed the extramural

built on. The learning technique [at university] is a lot placements office at the top of their support systems, with

more independent whereas in school was more ‘spoon- personal tutors and the school reception always rated

fed’ and about achieving grades rather than understand- among the top five support systems. The student ratings

ing the content.’’ of support were generally very similar between graduates

Students who reached the program through the pre- and school leavers. A few notable exceptions were ob-

liminary or gateway years generally felt better prepared served: the school leavers rated the student-IT helpdesk

for the veterinary program, which was also reflected in service more highly than graduates (median ¼ 32 for

their free-text comments: ‘‘[I] think the Gateway course school leavers and 16.5 for graduates, p ¼ .04), while

had good content however there weren’t many practicals graduates rated the university financial support service

with animals and most staff were not very supportive,’’ more highly (median ¼ 29 for graduates in comparison

‘‘The Gateway course helped me significantly and im- to 50 for school leavers, p ¼ .04). The ranked data (Table

proved my confidence,’’ and ‘‘There are many topics I 4) showed that the school leavers found the tutor family

had not covered in school before I came here. Some (two academics assigned to around six students per cohort

topics I have covered in the Gateway course which has plus one senior tutor per cohort), welfare drop-in session,

helped this year. None of my previous experience prepared and the peer support from other students of more impor-

me to manage my time effectively in order to cope with tance than the graduate students did.

the large workload. I have found that a lot of lecturers

presume we have already learned many topics and so

the basics in that area are not explained—just the more Academic Achievement Based on Previous

complicated in depth areas.’’ Education

Of the 109 students, 107 participated in the assessments at

the first assessment point (MSK and LCB). Two students

376 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1

students gained significantly higher grades than the

school leavers in the assessments at the first examination

time point: for the MSK spot test, the median was 61%

for graduates and 51% for school leaver (p ¼ .02); in the

LCB exams, the online median was 70% for graduates

and 61% for school leaver (p ¼ .04) and the spot median

was 66% for graduates and 61% for school leavers

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

(p ¼ .02). These results lead to significantly better overall

grades for graduate students in these two modules (MSK:

median ¼ 66% for graduates and 50% for school leavers,

p ¼ .04; LCB: median ¼ 69% for graduates and 62% for

school leavers, p ¼ .01). While there were no significant

differences in assessment performance at the second

assessment point, the earlier enhanced performance was

still significantly reflected in the overall year 1 grades

(median ¼ 68% for graduates and 61% for school leavers,

p ¼ .03; Table 5a and Figure 1). When international stu-

dents (3 graduates and 19 school leavers) were excluded

from this analysis, graduate students still performed better

than school leavers but the differences were no longer

significant (Table 5b). Comparing the end-of-year perfor-

mance per grade bracket, most graduate students were

in the 70%+ bracket followed by the 60–69% bracket,

compared with the school leavers, who mostly fell within

the 60%–69% bracket followed by the 50%–59% bracket

(Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

First-Year Learning Experience and

Performance

Our study has clearly highlighted that in the first year of

a veterinary medicine degree, graduate students initially

perform better with significantly higher grades in the first

assessment point, leading to an overall grade for year

1 that is 10% (on average) higher than that of school

leavers. This supports the view that graduate students

are already familiar with the university environment and

with the study approaches required to perform well.

In the only study comparing academic performance of

gradate-entry medical students and school-leaver entry

medical students completing the same pre-clinical curric-

ulum and assessments, the study showed that graduate-

entry students performed significantly but only marginally

better than school leavers over all four bioscience knowl-

edge assessments.16 However, students were only included

in the study if they passed the subject on their first attempt,

with the reasoning that a fail may not reflect their academic

Figure 1: Examination grades in each of the modules in the ability but may be due to health or personal reasons.16 In

first year of study our study, all assessment performances were included,

*p < .05 (based on the Mann–Whitney U test, two tailed except for students with valid medical or personal exten-

with 95% confidence interval) uating circumstances who had their exam performance

annulled if failed. While a fail in first-year assessments

may not be a true reflection of the students’ knowledge,

had extenuating circumstances and their assessment re- if no extenuating circumstances are present, it very likely

sults were obtained from their first sit in the re-sit period reflects their difficulty in transitioning to the veterinary

(August). All students participated in the second assess- program, be it the difference in teaching delivery, inde-

ment point (June). pendent learning, workload, or the university environ-

We evaluated all examination grades (online and spot ment as a whole. Our data clearly show that graduate

test; Figure 1) from the six modules of the first year of students perform significantly better in the early assess-

the veterinary medicine degree program. The graduate ment point, but by the second assessment point, this

doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC 377

Table 5a: Examination grades (all students)

Graduate School leaver

Module Exam type (n ¼ 25) (n ¼ 87) p

MSK Musculoskeletal 1 Online 69 (51–93) 64 (42–84) –

Spot 61 (42–84) 51 (22–76) .02

Module overall 66 (46–88) 60 (36–81) .04

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

LCB Lymphoreticular Cell Biology 1 Online 70 (32–87) 61 (32–87) .04

Spot 66 (47–86) 61 (25–89) .02

Module overall 69 (41–81) 62 (35–84) .01

CRS Cardiorespiratory 2 Online 64 (41–82) 59 (37–79) –

Spot 64 (32–81) 62 (34–83) –

Module overall 66 (39–82) 60 (38–81) –

NEU Neuroscience 2 Online 67 (0–90) 64 (35–84) –

Spot 72 (31–88) 64 (24–91) –

Module overall 69 (10–90) 63 (31–86) –

AHW Animal Health and Welfare 2 Online 70 (48–83) 66 (43–81) –

Spot 63 (33–89) 59 (22–81) –

Module overall 68 (48–82) 64 (38–77) –

PPS Personal, Professional Skills 3 IT project 70 (51–77) 67 (45–83) –

Overall grade 68 (40–83) 61 (18–81) .03

Values indicate median (minimum–maximum) examination grade (percentage). P values are shown in bold if significant (p < .05) based on

the Mann–Whitney U test. In the modules, 1 represents the first assessment period ( January), 2 represents the second assessment period

(June), and 3 represents course work during term time.

Table 5b: Examination grades (international students excluded)

Graduate School leaver

Module Exam type (n ¼ 21) (n ¼ 68) p

MSK Musculoskeletal 1 Online 68 (49–93) 67 (43–84) –

Spot 60 (32–79) 53 (35–77) –

Module overall 66 (43–88) 62 (43–81) –

LCB Lymphoreticular Cell Biology 1 Online 71 (44–85) 63 (45–87) –

Spot 69 (29–80) 62 (25–89) –

Module overall 69 (45–81) 63 (46–84) –

CRS Cardiorespiratory 2 Online 65 (41–79) 60 (37–83) –

Spot 64 (32–76) 64 (34–83) –

Module overall 66 (39–76) 63 (38–82) –

NEU Neuroscience 2 Online 67 (0–90) 64 (35–86) –

Spot 65 (31–88) 66 (24–91) –

Module overall 69 (10–90) 65 (31–86) –

AHW Animal Health and Welfare 2 Online 69 (50–80) 67 (43–83) –

Spot 63 (48–89) 63 (22–85) –

Module overall 65 (56–77) 65 (38–82) –

PPS Personal, Professional Skills 3 IT project 70 (56–77) 68 (45–83) –

Overall grade 66 (18–83) 63 (40–82) –

Values indicate median (minimum–maximum) examination grade (percentage). P values are shown in bold if significant (p < .05) based on

the Mann–Whitney U test. In the modules, 1 represents the first assessment period ( January), 2 represents the second assessment period

( June), and 3 represents course work during term time.

difference in assessment results is diminished. Some of factor. This is similar to the outcomes of a study compar-

this academic advantage may be due to prior obtained ing knowledge assessment outcomes between graduate

scientific knowledge but since this advantage is most students on a 4-year UK Graduate Entry Program (GEP)

likely at play in the early part of first year, it suggests for medicine with those of a conventional 5-year program,

that prior experience of tertiary education is an important showing that the GEP students performed significantly

378 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1

perceived personal need for the support offered. This

study showed that school leavers were more likely than

graduates to feel that their school experience had pre-

pared them well for university. This would certainly be

worth further investigation to uncover which skills are

perceived as being useful by both sets of students. It was

noted in our results that graduates are less likely to rate

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

the tutor family or their peers highly within their support

network. It is possible that these students rely on mecha-

nisms such as family/friends in their personal life more

than school leavers do, but it is also important to high-

light that friendships and social networks have been

found to be important factors relating to student reten-

tion.19 Would ‘‘mature students’’ benefit more from being

in mixed-age tutor groups or ‘‘mature student only’’ tutor

groups? Support tailored towards mature students has

been suggested. In 2011, the British government high-

Figure 2: End-of-year examination grade position lighted the need to attract as well as support mature stu-

End-of-year grade and percentage of students within both dents.20 It has also been observed that financial problems,

school leaver and graduate groups achieving over 70% confidence in ability, and perceived lack of support from

(first-class honors), 60%–69% (upper second-class honors), teaching staff caused problems for non-traditional learners,

50%–59% (lower second-class honors), and under 50% including mature students.21 Specialized support programs

(traditionally third-class honors, but a failure to continue for mature students, staff awareness training, a mature

in veterinary medicine) student survival guide, and orientations aimed at mature

students have also been suggested as ways to assist

mature students in forming peer networks and support

better than both school leavers and graduate students on systems.22 On the other hand, graduate students have

the 5-year program.12 This better performance may be the additional costs of a second degree. Compared to

due to differences in selection policy, structure of teach- school leavers, university financial support services are

ing, academic support, or the program working environ- seen by graduate students as a more important univer-

ment12; however, no data were presented or discussed sity support system even in year 1. Financial pressures

comparing the performance of graduate students and will potentially increase over the 5-year program, espe-

school leavers within the 5-year program. Further data cially due to EMS and clinical EMS, leading to fewer

analysis showed that this difference is mainly due to opportunities to work in teaching-free times and also in-

international students in the school-leaver group, con- creased costs in addition to the very intensive fifth-year

firming again that transition to university is challenging, rotations. Some of these graduate students are also more

especially if that also means a different cultural or lan- likely to have differing family and financial responsibil-

guage environment. ities (e.g., partners, children, responsibilities as caregivers

In contrast to the marked difference in student per- for parents, mortgages, differing loan and/or bursary

formance, the perception of their first-year experience is opportunities) and they are more likely to have been in

very similar for both groups, reflecting that the veterinary the workplace and have taken a large drop in wages

medicine degree program has a higher workload and compared to school/college leavers. The long-term im-

faster pace than some other degree programs. The main pact on the increase in fees at UK universities, especially

differences include that graduate students are more con- in the long and intense programs such as medicine and

fident in their ability to cope with the program and to veterinary medicine, still needs to be established. While

understand the course materials. medicine and veterinary medicine are professional degrees

with currently good employment opportunities, it still

needs to be determined if studying in those programs as

Student Support a second degree is financially viable.

Student support is very important since the pressures Institutions of higher education are experiencing in-

listed above and the associated stress can lead to mental creased governmental, institutional, and market pressure

health problems. Up to a third of students surveyed in to achieve high standards in education while also pro-

their first year at a veterinary school reported clinical viding higher levels of support, especially as education

levels of depression and elevated anxiety levels.17,18 The increases in price.6 This has led to the view that students

main causes reported were homesickness, academic con- have become ‘‘customers’’ rather than beneficiaries of

cerns, difficulty fitting in with peers, and poorer perceived tertiary education.6 Hence universities have to find a

physical health. The University of Nottingham and the balance between listening to their students and acting

School of Veterinary Medicine and Science offer a range upon student feedback, thus ensuring that they attract

of support systems to avoid the escalation of stress and and maintain the best students but also maintain educa-

anxiety levels. However the rating of those support sys- tional standards so that degrees are not simply obtained

tems by the students is variable, probably reflecting the

doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC 379

because a student pays enough money. The financial re- SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

turn of a degree depends upon the degree subject, institu- It has previously been suggested that ‘‘treating people

tion attended, and class of degree obtained. It is therefore fairly does not mean treating people in the same way—

essential that all students be provided with an equal we need to recognize difference and respond appro-

chance through the university support systems to excel priately.’’27(p.197) It is the conclusion of this study that

at their studies and enhance their lifelong chances of graduate students and school leavers have very different

financial reimbursement for their studies. This is espe- educational and support needs, and that education pro-

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

cially important for graduate students who invest into a viders need to be aware of these differences to respond

very long secondary degree program with little opportu- and provide accordingly.

nity to work in lecture-free time due to work placements. Understanding the requirements and abilities of students

In a Finnish study of first-year student perceptions and who have prior university experience is very important.

performance in an macroscopic anatomy module (one Towards the end of first year, graduate students in our

of the first modules), prior university experience did study perceived transition into the highly demanding

not significantly improve performance but it did reduce veterinary degree program as easier with regards to course

stress levels.23 Even though many first-year students in material and prior knowledge. This difference between

countries such as the US already have degrees, their graduate students and school leavers was also reflected

experience of the university learning environment, the in assessment performance, with graduate students’ signif-

intensity of the course program, the time commitment, icantly better results in the early assessments leading to

and the large amount of information to learn and memo- significantly better grades at the end of year 1 even

rize can still be very challenging.24,25 The impact of this though the performance of both groups of students was

high workload may also reflect surface approaches to similar in the end-of-year assessments.

learning, which are negatively associated with grades

achieved in assessments.26

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A descriptive study like this one has some limitations

The authors would like to thank Debbie Coutts for collat-

that need to be acknowledged. This study was performed

ing information on cohort intake, the Teaching, Learning

in a UK university with the majority of students moving

and Assessment office for collating cohort examination

straight form secondary education to university, which is

grades, Mrs. Aziza Alibhai for assisting with ques-

common in European countries but different from coun-

tionnaire data, and Dr. Kate Cobb for intellectual input

tries such as the US, where students who enter veterinary

(University of Nottingham, School of Veterinary Medicine

medicine have already obtained an undergraduate degree.

and Science).

However, the recommendations for graduate students

will still be relevant. While there was a high return rate

for the questionnaire, only very few students answered REFERENCES

the free-text questions and hence no qualitative analysis 1 Astin A. Achieving educational excellence. San

was possible. Focus groups and face-to-face interviews Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1987.

might have yielded more in-depth information. The 2 Johnson GM. Undergraduate student attrition: a

sample size was relatively small, so caution should be comparison of the characteristics of students who

used when generalizing these data. withdraw and students who persist. Alberta J Educ Res.

1994;40(3):337–53.

Recommendations and Educational 3 Pascarella ET, Terenzini PT. How college affects

students: findings and insights from twenty years of

Implications research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1991.

e Information about support systems needs to be high-

4 Blythman M, Orr S. A joined-up policy approach to

lighted proactively at several times throughout first student support. In: Peelo MT, Wareham T, editors.

year, especially around revision and exam result Failing students in higher education. Buckingham, UK:

release times, to ensure that all students are aware of Open University Press and SRHE; 2003. p. 45–55.

the support available. 5 McInnis C, James R, McNaught C. First year on campus:

e Students should feel that identifying problem areas

diversity in the initial experiences of Australian

and seeking help/support are seen as strengths and undergraduates. Melbourne: Centre for the Study of

signs of good professionalism. Higher Education, University of Melbourne; 1995.

e University support needs to be aware of the specific

6 Dent JA, Rennie S. Student support. In: Dent JA, Harden

needs/stress points of veterinary students, especially RM, editors. A practical guide for medical teachers. 2nd

around time management and workload in com- ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2005.

parison to some other degree programs in order 7 Thomas E, Quinn J. First generation entry into higher

to provide suitable coping strategies as well as education: an international study. 1st ed. Maidenhead,

academic and financial advice. UK: McGraw-Hill International; 2007. p. 84.

e Tutors and welfare staff need to be aware that grad-

8 Woodley A. The older the better? A study of mature

uate students, although familiar with the university student performance in British universities. Res Educ.

environment, may still find the workload and time- 1984;32:35–50.

intensive teaching of the veterinary curriculum over- 9 Richardson JTE, Woodley A. Another look at the role of

whelming. In addition, financial support options and age, gender and subject as predictors of academic

coping strategies should be proactively discussed attainment in higher education. Stud High Educ.

with graduate students.

380 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1

2003;28(4):475–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ uploads/attachment_data/file/32404/11-728-guidance-

0307507032000122305. to-director-fair-access.pdf.

10 Bourner T, Hamed M. Entry qualifications and degree 21 Leathwood C, O’Connell P. ‘It’s a struggle’: the

performance. London: Council for National Academic construction of the ‘new student’ in higher education. J

Awards; 1987. Educ Policy. 2003;18(6):597–615. http://dx.doi.org/

11 Hayes K, Feather A, Hall A, et al. Anxiety in medical 10.1080/0268093032000145863.

students: is preparation for full-time clinical attachments 22 Tones M, Fraser J, Elder R, et al. Supporting mature-

${protocol}://jvme.utpjournals.press/doi/pdf/10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 - Saturday, July 21, 2018 12:37:58 AM - University of Arizona IP Address:150.135.135.69

more dependent upon differences in maturity or on aged students from a low socioeconomic background.

educational programmes for undergraduate and High Educ. 2009;58(4):505–29. http://dx.doi.org/

graduate entry students? Med Educ. 2004;38(11):1154– 10.1007/s10734-009-9208-y.

63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01980.x 23 Laakkonen J, Nevgi A. Relationships between learning

Medline:15507009 strategies, stress, and study success among first-year

12 Price R, Wright SR. Comparisons of examination veterinary students during an educational transition

performance between ‘conventional’ and Graduate phase. J Vet Med Educ. 2014;41(3):284–93. http://

Entry Programme students; the Newcastle experience. dx.doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0214-016R1 Medline:24981421

Med Teach. 2010;32(1):80–2. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/ 24 Sutton RC. Veterinary students and their reported

01421590903196961 Medline:20095780 academic and personal experiences during the first year

13 Shehmar M, Haldane T, Price-Forbes A, et al. of veterinary school. J Vet Med Educ. 2007;34(5):645–51.

Comparing the performance of graduate-entry and http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/jvme.34.5.645

school-leaver medical students. Med Educ. Medline:18326777

2010;44(7):699–705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365- 25 Chigerwe M, Ilkiw JE, Boudreaux KA. Influence of a

2923.2010.03685.x Medline:20636589 veterinary curriculum on the approaches and study

14 Powers DE. Student perceptions of the first year of skills of veterinary medical students. J Vet Med Educ.

veterinary medical school. J Vet Med Educ. 2011;38(4):384–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/

2002;29(4):227–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ jvme.38.4.384 Medline:22130414

jvme.29.4.227 Medline:12717641 26 Ryan MT, Irwin JA, Bannon FJ, et al. Observations of

15 Tait H, Entwistle N, McCune V. ASSIT: A veterinary medicine students’ approaches to study in

reconceptualisation of the approaches to studying pre-clinical years. J Vet Med Educ. 2004;31(3):242–54.

inventory. In: Rust C, editor. Improving student http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/jvme.31.3.242

learning: improving students as learners. Oxford: Medline:15510339

Oxford Center for Staff and Learning Development; 27 McKimm J, Swanwick T. Clinical teaching made easy:

1998. p. 262–71. a practical guide to teaching and learning in clinical

16 Dodds AE, Reid KJ, Conn JJ, et al. Comparing the settings. London, UK: Quay Books; 2010.

academic performance of graduate- and undergraduate-

entry medical students. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):197–204. AUTHOR INFORMATION

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03559.x Catrin S. Rutland, BSc (hons), MSc, PhD, PGCHE, MMedSci,

Medline:20059678 SFHEA, FAS, is Assistant Professor in Anatomy and

17 Hafen M Jr, Reisbig AMJ, White MB, et al. Predictors of Developmental Genetics, School of Veterinary Medicine and

depression and anxiety in first-year veterinary students: Science, University of Nottingham, College Rd, Sutton Bonington

a preliminary report. J Vet Med Educ. 2006;33(3):432–40. Campus, Loughborough LE12 5PE, UK. Email:

http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/jvme.33.3.432 catrin.rutland@nottingham.ac.uk. Her research interests include

Medline:17035221 student welfare, support, and pedagogical experience, as well as

18 Hafen M Jr, Reisbig AM, White MB, et al. The first-year international study.

veterinary student and mental health: the role of

common stressors. J Vet Med Educ. 2008;35(1):102–9. Heidi Dobbs, MChem, PGCE, is Teaching Associate, School of

http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/jvme.35.1.102 Veterinary Medicine and Science, University of Nottingham,

Medline:18339964 College Rd, Sutton Bonington Campus, Loughborough LE12 5PE,

19 Thomas L. Student retention in higher education: the UK, and RSC Education Coordinator, Midlands, School of

role of institutional habitus. J Educ Policy. Chemistry, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham

2002;17(4):423–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ NG7 2RD, UK. Email: heidi.dobbs@nottingham.ac.uk.

02680930210140257. Sabine Tötemeyer, Dipl Biol, PhD, PGCHE, SFHEA, MAHEd, is

20 Cable C, Willetts, D. Guidance to the director of fair Lecturer in Cellular Microbiology, School of Veterinary Medicine

access [Internet]. London: Secretary of State for Business, and Science, University of Nottingham, College Rd, Sutton

Innovation and Skills and Minister for Universities and Bonington Campus, Loughborough LE12 5PE, UK. Email:

Science; 2011 [cited 2016 May 4]. Available from: sabine.totemeyer@nottingham.ac.uk. Her research interests

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/ include admissions, the first-year experience, and student welfare.

doi: 10.3138/jvme.0915-145R1 JVME 43(4) 8 2016 AAVMC 381

You might also like

- Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student AttritionFrom EverandLeaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student AttritionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Business JourneyDocument10 pagesBusiness Journeyquanhle2005No ratings yet

- Lizzi o 2002Document28 pagesLizzi o 2002MelisawiNo ratings yet

- Theory Into Practice: To Cite This Article: J. Randy Mcginnis (2013) Teaching Science To Learners With Special NeedsDocument9 pagesTheory Into Practice: To Cite This Article: J. Randy Mcginnis (2013) Teaching Science To Learners With Special Needsรณกฤต ไชยทองNo ratings yet

- 5 RRLDocument3 pages5 RRLbjkaunlaranbambangbranchNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Special Education A Comprehensive ApproDocument7 pagesRethinking Special Education A Comprehensive ApprophyNo ratings yet

- Article 2023Document8 pagesArticle 2023solon.mykelesterbNo ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Pauli 12 10 21Document10 pagesCSTP 1 Pauli 12 10 21api-556979227No ratings yet

- Roach2004 - Evaluating School Climate and School Culture Andrew T. Roach - Thomas R. KratochwDocument8 pagesRoach2004 - Evaluating School Climate and School Culture Andrew T. Roach - Thomas R. KratochwAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Devlin 2002Document16 pagesDevlin 2002plinhchi1703No ratings yet

- Limitations in Public Ecuadorian ClassroomsDocument1 pageLimitations in Public Ecuadorian ClassroomsDamaris Lopez BobadillaNo ratings yet

- 3 CEQS Assessment (No Questions Provided 37th Question For General Satisfaction Is Here Though!)Document9 pages3 CEQS Assessment (No Questions Provided 37th Question For General Satisfaction Is Here Though!)Chynna ReyesNo ratings yet

- DataDocument1 pageDataapi-351067106No ratings yet

- Journal Academic Remediation-FocusedDocument11 pagesJournal Academic Remediation-FocusedHamidah IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1Document2 pagesPractical Research 1Lemuel Matin-aoNo ratings yet

- CSTP 6 Basani 4Document12 pagesCSTP 6 Basani 4api-518571218No ratings yet

- cstp1 EspalinDocument9 pagescstp1 Espalinapi-573214664No ratings yet

- SSRN Id4325530Document15 pagesSSRN Id4325530Jerry F. Abellera Jr.No ratings yet

- Advanced Visual Argument - Research Poster 1Document2 pagesAdvanced Visual Argument - Research Poster 1api-357042958No ratings yet

- FEU Assessment Policies and GuidelinesDocument14 pagesFEU Assessment Policies and GuidelinesAntoinette SangcapNo ratings yet

- Handbook of SelfRegulation of Learning and Performance. Capítulo 27Document17 pagesHandbook of SelfRegulation of Learning and Performance. Capítulo 27Relmu ArcoirisNo ratings yet

- Exm - Quantifying Difficulties of University Students With DisabilitiesDocument17 pagesExm - Quantifying Difficulties of University Students With Disabilitieshanis farhanaNo ratings yet

- BSIT students course influences at Leyte Normal UniversityDocument9 pagesBSIT students course influences at Leyte Normal UniversityrommelNo ratings yet

- A Study of Academic Procrastination in College StudentsDocument70 pagesA Study of Academic Procrastination in College StudentsVampyy GalNo ratings yet

- ShortstoryDocument14 pagesShortstoryAtasha Xd670No ratings yet

- RRLaS Matrix Factors Affecting Students' Career ChoicesDocument4 pagesRRLaS Matrix Factors Affecting Students' Career ChoicesAngel SisonNo ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Cunningham 3Document7 pagesCSTP 1 Cunningham 3api-518590777No ratings yet

- 43bceae6698a1fffe6fe7014cff6af8fDocument21 pages43bceae6698a1fffe6fe7014cff6af8fsalsabila pujiani gubaNo ratings yet

- Move 1,2,3 Position Paper ExampleDocument5 pagesMove 1,2,3 Position Paper ExampleEthan Erika BionaNo ratings yet

- Thesis IntroDocument8 pagesThesis IntroRiot GamesNo ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Pedue 12Document9 pagesCSTP 1 Pedue 12api-622185749No ratings yet

- Mga Sites AhDocument4 pagesMga Sites AhDianne PanNo ratings yet

- CSTP 1-6 Marsh 9Document49 pagesCSTP 1-6 Marsh 9api-707772485No ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Coronado 12Document6 pagesCSTP 1 Coronado 12api-679271268No ratings yet

- Os Mpa-2021Document20 pagesOs Mpa-2021BurgerqueennNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Arts Education and Special Education Policy, Research, and PracticesDocument14 pagesHandbook of Arts Education and Special Education Policy, Research, and PracticesVasia PapapetrouNo ratings yet

- Ej 1137898Document14 pagesEj 1137898Bianca Nicole MantesNo ratings yet

- Role and Requirement of Students and Teachers in Quality Enhancement of Higher Education InstitutionsDocument4 pagesRole and Requirement of Students and Teachers in Quality Enhancement of Higher Education InstitutionsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Karli Keller cstp1 2009 1Document7 pagesKarli Keller cstp1 2009 1api-637097800No ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Steiss 7Document8 pagesCSTP 1 Steiss 7api-678983495No ratings yet

- AnalysisDocument3 pagesAnalysisjeth.lungayNo ratings yet

- Gaps IdentifiedDocument6 pagesGaps IdentifiedAnjie CabalcarNo ratings yet

- CTSP 1 Butterbrodt 7Document6 pagesCTSP 1 Butterbrodt 7api-679216509No ratings yet

- (ASSIGMENT #1) Type of Test and AssessmentDocument3 pages(ASSIGMENT #1) Type of Test and AssessmentKarl Angelo ReblandoNo ratings yet

- Standard 1 CSTP: Engaging and Supporting All Students in LearningDocument7 pagesStandard 1 CSTP: Engaging and Supporting All Students in LearningKaitlyn AprilNo ratings yet

- High School Students' Perception of Challenges in Physics Learning and Relevance of Field DependencyDocument8 pagesHigh School Students' Perception of Challenges in Physics Learning and Relevance of Field DependencyYamin HtikeNo ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Ocampo 09Document11 pagesCSTP 1 Ocampo 09api-635281515No ratings yet

- The National Academies PressDocument7 pagesThe National Academies PressZehra ZahidNo ratings yet

- Students' Feedback and Challenges Encountered On Modular Distance Learning: Its Relationship To Their Academic Performance in ScienceDocument28 pagesStudents' Feedback and Challenges Encountered On Modular Distance Learning: Its Relationship To Their Academic Performance in SciencePsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological Study of Bukidnon State University Graduate Student ScholarsDocument10 pagesPhenomenological Study of Bukidnon State University Graduate Student ScholarsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Group Activity 2 Unit 1Document6 pagesGroup Activity 2 Unit 1tripon1552No ratings yet

- Higher Education Seen From Inside: The Case of Electrical Engineering StudentsDocument5 pagesHigher Education Seen From Inside: The Case of Electrical Engineering Studentsdilan bro SLNo ratings yet

- Using Survey of Academic Orientations to Predict Student Stress LevelsDocument8 pagesUsing Survey of Academic Orientations to Predict Student Stress LevelsCrizalyn AciertoNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its Setting: Quezonian Educational College Inc. Senior High School DepartmentDocument6 pagesThe Problem and Its Setting: Quezonian Educational College Inc. Senior High School DepartmentJOEMER TARACINANo ratings yet

- Definition of The Concept CompetencyDocument8 pagesDefinition of The Concept CompetencyLina KetfiNo ratings yet

- 14cheryan Etal Meltzoff Designing ClassroomsDocument9 pages14cheryan Etal Meltzoff Designing ClassroomsCayner CuritanaNo ratings yet

- cstp1 Nguyen 071323Document7 pagescstp1 Nguyen 071323api-621911859No ratings yet

- Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University College of Graduate StudiesDocument5 pagesDon Mariano Marcos Memorial State University College of Graduate StudiesMICHAEL STEPHEN GRACIASNo ratings yet

- Achieving and Sustaining Institutional Excellence for the First Year of CollegeFrom EverandAchieving and Sustaining Institutional Excellence for the First Year of CollegeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Phuong Phong Cach PR p1Document34 pagesPhuong Phong Cach PR p1Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Thuy Hang PR Ly Luan Va Ung Dung p1Document31 pagesThuy Hang PR Ly Luan Va Ung Dung p1Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Phuong Phong Cach PR p2Document24 pagesPhuong Phong Cach PR p2Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Group 2Document39 pagesGroup 2Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- (G1) Managing The ClassroomDocument60 pages(G1) Managing The ClassroomNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Phonetics 02 PhonemesDocument5 pagesPhonetics 02 PhonemesNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- (Giáo Trình) Going International - English For TourismDocument186 pages(Giáo Trình) Going International - English For TourismNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- (G2) Describing Learning & TeachingDocument30 pages(G2) Describing Learning & TeachingNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Phonetics 03 SyllableDocument3 pagesPhonetics 03 SyllableNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- (GP) Teaching Vocabulary - RevisedDocument3 pages(GP) Teaching Vocabulary - RevisedNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Phonetics 04 StressDocument3 pagesPhonetics 04 StressNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Academic Background & Course Involvement as Predictors of Exam PerformanceDocument5 pagesAcademic Background & Course Involvement as Predictors of Exam PerformanceNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Phonetics - 05 - Weak FormsDocument2 pagesPhonetics - 05 - Weak FormsNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Understanding IntonationDocument6 pagesUnderstanding IntonationNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- SAMPLE Phonology Test-1Document2 pagesSAMPLE Phonology Test-1Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- SAMPLE Phonology Test-1Document2 pagesSAMPLE Phonology Test-1Nguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Phonetics and Phonology - SampleDocument6 pagesPhonetics and Phonology - SampleNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- BA-IRM-Final Test-2021-JulyDocument1 pageBA-IRM-Final Test-2021-JulyNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Self-Enhancing and Self-Defeating Ego Goals in MatDocument24 pagesSelf-Enhancing and Self-Defeating Ego Goals in MatNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Phonetics and Phonology - SampleDocument6 pagesPhonetics and Phonology - SampleNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- (123doc) A Contrastive Analysis Between The Verb Run in English and The Verb Chay in VietnameseDocument52 pages(123doc) A Contrastive Analysis Between The Verb Run in English and The Verb Chay in VietnameseNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Sample Test 2 KeyDocument5 pagesSample Test 2 KeyNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- TWEEDIE 2017-Scholarly Works Item 1.4 Comparison of IELTS TOEFL EAP in NursingDocument23 pagesTWEEDIE 2017-Scholarly Works Item 1.4 Comparison of IELTS TOEFL EAP in NursingNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Intro To Lit-5.2021-CLC-TONG HOPDocument5 pagesIntro To Lit-5.2021-CLC-TONG HOPNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Vietnam National University exam final methodology teachingDocument2 pagesVietnam National University exam final methodology teachingNguyễn Trần Bá ToànNo ratings yet

- Motivation LetterDocument2 pagesMotivation LetterBabar MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Enrolment 2022 2023.ShsDocument10 pagesEnrolment 2022 2023.ShsLaVictoria SuccuZen GardenNo ratings yet

- Qualifications and Other Details For Appointment of TeachersDocument5 pagesQualifications and Other Details For Appointment of TeachersYogesh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Background and Work ExperienceDocument8 pagesBackground and Work ExperienceElena EreminaNo ratings yet

- Basic Physics Micro Project ReportDocument10 pagesBasic Physics Micro Project ReportLaptop DellNo ratings yet

- Schools in Uttar Pradesh: Rahul Motiawaet SchoolDocument12 pagesSchools in Uttar Pradesh: Rahul Motiawaet SchoolRavi Prakash RaoNo ratings yet

- Student FlowDocument1 pageStudent FlowNURUL SHAHINAZ BINTI AMIRUDDINNo ratings yet

- HSC ListDocument8 pagesHSC Listms_55100% (1)

- University of Mauritius: A: Student Disclosure/Undertaking Under Free Tertiary Education Scheme (Ftes)Document2 pagesUniversity of Mauritius: A: Student Disclosure/Undertaking Under Free Tertiary Education Scheme (Ftes)Boodhram NeilNo ratings yet

- Affix Your Self-Attested Recent Passport Size Photograph HereDocument8 pagesAffix Your Self-Attested Recent Passport Size Photograph Herekonga121No ratings yet

- Karnataka Common Entrance Test 2010Document3 pagesKarnataka Common Entrance Test 2010premsempireNo ratings yet

- Analytical Report: Extra-Curricular Activities Name: Shaan Rashad Saifullah Class: Grade 10 Section: 3 Roll No.: 23Document1 pageAnalytical Report: Extra-Curricular Activities Name: Shaan Rashad Saifullah Class: Grade 10 Section: 3 Roll No.: 23arif asgarNo ratings yet

- Ralph Bunche Application PDFDocument3 pagesRalph Bunche Application PDFAndre AndersonNo ratings yet

- ESE 19 Cut Off MarksDocument1 pageESE 19 Cut Off MarksvikasNo ratings yet

- 384 Yearbook EngDocument83 pages384 Yearbook EngwizzytrippzNo ratings yet

- Admissions 1Document1 pageAdmissions 1The real LeaderNo ratings yet

- Education System in JapanDocument8 pagesEducation System in JapanAsobina SanNo ratings yet

- Seminar Report Front PagesDocument3 pagesSeminar Report Front PagesBandari Chandu YadavNo ratings yet

- Iraq EducationDocument10 pagesIraq EducationAhmed Al-IraqiNo ratings yet

- "Basic Technician Certificate in Leather Products Technology "Programme For The Academic Year 2016/2017 Scheduled To Commence in March/April 2017.Document3 pages"Basic Technician Certificate in Leather Products Technology "Programme For The Academic Year 2016/2017 Scheduled To Commence in March/April 2017.Muhidin Issa MichuziNo ratings yet

- Analisis & Post-Mortem Keputusan SPM 2021Document40 pagesAnalisis & Post-Mortem Keputusan SPM 2021DYMPHINA J. JOHN MoeNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra Diploma Admission Receipt and StatusDocument1 pageMaharashtra Diploma Admission Receipt and StatusParner TehsilNo ratings yet

- MARK SCHEME For The November 2005 Question PaperDocument2 pagesMARK SCHEME For The November 2005 Question PaperSerenaNo ratings yet

- Bedford Borough Establishment Guide Apr 15Document15 pagesBedford Borough Establishment Guide Apr 15Mirela TudorNo ratings yet

- Marks Sessionals ON 2014Document167 pagesMarks Sessionals ON 2014ArnavGargNo ratings yet

- List of Schools in MaduraiDocument44 pagesList of Schools in MaduraiTech Ocean100% (1)

- Unisa Higher Certificates and The Related Qualifications Per CollegeDocument5 pagesUnisa Higher Certificates and The Related Qualifications Per CollegeAlenNo ratings yet

- Class XII INTEGRATION Most Important Questions For 2023-24 Examination (Dr. Amit Bajaj)Document118 pagesClass XII INTEGRATION Most Important Questions For 2023-24 Examination (Dr. Amit Bajaj)tejasbhai653No ratings yet

- TRC NewResidentScholarships-2022 0721-v2 PDFDocument4 pagesTRC NewResidentScholarships-2022 0721-v2 PDFBig DogNo ratings yet

- Mindler Exam Newsletter 22 Aug'22Document2 pagesMindler Exam Newsletter 22 Aug'22Uttkarsh SrivastavaNo ratings yet