Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ashok Aklujkar

Uploaded by

mkmartandCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ashok Aklujkar

Uploaded by

mkmartandCopyright:

Available Formats

ANCIENT INDIAN SEMANTICS

Author(s): Ashok Aklujkar

Source: Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute , 1970, Vol. 51, No. 1/4

(1970), pp. 11-29

Published by: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41688671

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41688671?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Annals of the

Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ANCIENT INDIAN SEMANTICS*

By

Ashok Aklujkar

1. 1

The present paper is a study of ancient Indian semantic1

comparative point of view, the comparison being with the s

that has developed in relatively recent times in the West.8 Wit

rison in mind, one could study Indian semantics in two ways

could compare its history, as far as it is known, with that of

semantics, and ( ii ) one could select certain problems of semantic

either in the Indian tradition or in the western tradition and examine

whether those problems have been raised in the other tradition and, if

raised, how they have been raised and discussed. The first way would

take the research to a study of some facts of literary history and of

ideas about semantics while the second would take him to a study of

ideas in the semantics. In the present paper I plan to follow the first

way ; I shall here compare the histories of Indian and Western

semantics.

1. S

The present study is thus very ambitious in its scope and cannot

help being sketchy rather than thorough. However, since it tries to

* Paper read in the South Asia ( linguistica and philology ) section of the

Twenty-seventh International Congress of Orientalists. The author is grateful to

Dr. Ronald E. Asher ( University of Edinburgh ) for suggesting stylistic improvement!

in the first draft of this paper.

1 I use the word c semantics ' in the sense 6 study-science-general theory of

meaning ' I do not include in semantics the study-science-general theory of

reference-referent-denotatum. The problem of the relation between reference and

meaning which is a border-line problem and which is perhaps as important in the

study of meaning as it is in the study of reference, is not excluded from semantics by

the restriction of the term Semantics ' in the above manner. There is no reason why

we should treat any related branches of human knowledge as water-tight compart-

ments. For the history of the word ' semantics 'f see Read ( 1948 ). N oreen uses the

term c semology ' ( Malmberg 1964 : 124 ) which is again taken up recently by Joos

( 1958 ). German linguists usually prefer the term ( semasiology ' ; cp. Kronasser

( 1952 ). For a distinction between semasiology and onomasiology, see Malmberg

( 1964 : 124 ).

2 For the sake of brevity, I drop the adjectives ( ancient ' and c modern-

relatively recent ' from the phrases ' ancient Indian' and < modern-relatively recent

western ' in the following pages. I am aware of the fact that the West also has sn old

tradition of semantic thought.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1Ž Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

cover a large number of facts and aspects it may help in having a correct

perspective of Indian semantics. It may, perhaps too broadly, indicate

the peculiarities of the Indian semantic tradition, the amount of credit

or discredit that the Indian tradition should historically receive and thi

degree of the relevance the Indian tradition has to modern western

semantics. This paper is thus an introduction to Indian semantics1 and

a contribution to the history of linguistics.

1. S

One could begin the comparison either from the point of view of

the Indian tradition or of the western tradition ; that is, one could start

with the facts known about either tradition and try to see whether any-

thing corresponds to those facts in the other tradition and, if something«

corresponding is found, to what extent the correspondence goes. I have

preferred to start the comparison from the point of view of the western

tradition. My preference has been governed by some practical consi- v

darations. In the first place, more is known about the western tradition

than is about the Indian tradition ; it facilitates understanding and :

1 There is no paucity as such of material on Indian semantic thought. What i«

lacking is a clear, well-ordered and comprehensive treatment of this subject in,

rigorously chosen English by a mind that has full grasp of the Sanskrit Sftsttic

' theoretical ' texts and profound awareness of the relevance of this áubject to

problems in modern linguistics and philosophy. Writings of Chakravarti ( 1930, 19 331 )*

Gaurinath Sastri ( 1959 ), Bhattacharya ( 1962 ) and Pandeya ( 1963 ) are disappoint-

ing frpm this point of view though they are sufficiently comprehensive and have "

helped some scholars in approaching the original Sanskrit texts. Kunjunni Raja

( 1963 ) is aware of the importance of the subject for modern studies, writes in terms

clearer than those of his predecessors and offers some interesting observations ; but the

order of his discussions is not always satisfactory and the statements of the *rgu- ~

ments advanced by different Indian schools of thought have not been given adequate :

place in his book. He devotes insufficient space to the discussion of Bhartrhari's

views and does not present them in the light of Bhartrhari's philosophy as a whole.

In general, his book suffers from its impressive scope. Biardeau ( 1964), in contrast ,

to Kuujunni Baja, devotes almost half of her book to the discussion of Bhartrhari's

views but does not point out the relevance it has to modern linguistic and philoso-

phical thinking. Her assumption that the FVM »-commentary on the Väkya-padiya -,

is not from Bhartrhari's pen, is unjustified ( see Aklujkar forthcoming ) and has led

her to asserting a number of unconvincing and unwarranted fine theoretical distipc- .

tions between the views of Bhartrhari and that of the so-called var¿¿»-commentator.

Her book is a mine of interesting philological data in the field of linguistic philosophy .

of the Indians ; but one can not always be sure of her interpretation of the texts and i

of the conclusions she arrives at. Both Biardeau and Kunjunni Raja give a very

helpful bibliography on Indian linguistic tradition in general which can be supple-

mented by Ruegg ( 1959 ) and Staal ( 1960 ). A remarkably clear and accurate account. .

of the semantic thought in Sanskrit poetics is given in the Marãthl edition of ř

Mammata's Kãvya-prakãêa by Arjunwadkar and Mangrulkar ( 1962 ). , »

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 13

gives a better judgement of the relevance if Indian

the light of western semantics. Secondly, the w

not present the problem of interpretation of te

which the Indian tradition, because of its ancient ch

of its current interpretations, presents it. It is

something that is relatively far more certain tha

is, at least for the present, subject to different int

the semantic problems have been raised more ex

tradition than in the Indian tradition. If therefore we start with the

western tradition before us, we have a better chance of making comments ř

about well-defined topics than we would otherwise have. Finally, more

factual information is available about the western semantic tradition

than is about the Indian semantic tradition.1 So, if we start the comp

rison with the western tradition in view, the move enables us to stu

the Indian semantic tradition from more points of view than we wou

otherwise be able to. For all these reasons I have decided to look at

the Indian semantic tradition from the point of view of the wes

semantic tradition, though my first and better acquaintance has

with the Indian semantic tradition and though the other point of

proves to be more profitable and convenient in some other compar

studies of Indian semantics.

1.4

In many places I speak of the Indian semantic tradition in general.

My main reliance, however, is on Bhartrhari's Vâkya-padïya 2 which is

the earliest available ( fourth century A. D. ) and extensive work of

Indian semantics. Though it is not primarily devoted to semantics and ,

though it makes no claim of originality of views, it is perhaps the most -

important work in what survives of the Indian semantic tradition ; it

has influenced the ideas of all later Indian semanticists and deals with

the semantic problems quite extensively though semantics is but one

part of its scope. Most of the evidence for what I want to point out .

comes from this work. As I am concerned here with broad

comparisons between two traditions and not with the

of individual ideas back in time in any one tradition, I do no

necessary either to be exhaustive in my references when I make

point or to find out the earliest evidence in support of what

sufficient for my present purposes to produce some textual evid

a particular point made in connection with either tradition.

1 These last two points should be added to the points in section 2 of

2 In my opinion, the name of Bhartrhari's magnum opus , taken as

Trihãndi ; the title Vãkyapadiya applies only to its first two books. See Aklujkar •>

( forthcoming ). I also hold the view that the vrtti is Bhartrhari's work and that it is

an inseparable part of the Vãkyapadiya ( see footnote 1 on p. 12 )#

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Í4 Ánnals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

1. 6

So far I have used the expressions ' Indian semantics ' and i Indian

semantic tradition ' without raising the question whether there is any

referent for these expressions. We know for sure that the West has a

branch of study named ' semantics ' which has been distinguished from

some other branches of study at least from Bréal's time;1 but such a

fact has not been as yet established in the case of the Indian linguistic,

logical or philosophical tradition.2 I therefore have to answer the follow-

ing four questions before I proceed with the use of the expressions

1 Indian semantics ' and 'Indian semantic tradition'; ( i ) Is there any

body of Sanskrit literature that is exclusively concerned with the study

of meaning ? ( ii ) If such a body of literature exists, does it have any

specific name ? ( iii ) Are all the topics that are topics of semantics in

the West discussed in this literature ? That is, how much justified is

the transfer of the word 'semantics' to the Indian scene ? ( iv ) Is the

qualification ' Indian ' necessary ? What is distinctively Indian about

this semantics ? Or, is it Indian only because it developed in India ?

What follows the present introductory section in this paper and

many more papers on which I am working at present, are an indirect

answer to the last two questions. By studying the information that I

supply there and by judging the logic that I use there, the reader can

decide for himself how far the transfer of the word ' semantics ' is justi-

fied and how far the Indian semantics is ť Indian ' As for myself, I

answer both the questions in the affirmative ; I think that there is

enough similarity between the western semantics and the Indian studies

of meaning to justify the latter's being referred to by the term

1 semantics ' ; I also think that there are certain historical, methodologi-

cal and expressional peculiarities of the semantics that developed in

India3 to justify its being qualified by the adjective 'Indian '

Before I touch upon the first question, it would be worth point-

ing out that we need not have a body of literature that is exclusively

devoted to the study of meaning to be justified in saying that a language

1 Bréal introduced the terna ť sémantique 1 in an article in 1883 for the first time

( Malmberg 1964 : 123 ). His ' Eassai de sémantique . science des significations 9 was

first published in 1897. Ullmann ( 1966 : 217 ) informs us that in 1820's Reisig had

thought of ' semasiology

2 Staal ( 1966 : 304-311 ) points out that if the Indian ideas are presented in a

careful manner the existence and the relevance of Indian semantic thought would be

acknowledged. As will be noticed below, my approach is different in that I assume

the existence of semantic ideas in the Indian tradition and try to prove the

existence of a body of literature devoted to what we refer to as semantic problems

or topics.

3 This point should be added to the points in section 2.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 15

or a tradition has semantics. Even wh

language or tradition is tied to studies of

scattered through different systems of

results of such study are not brought toge

can say that the language or the tradi

existence of semantic thought is a more

the grouping. In the western tradition, w

number of discussions that are exclus

meaning is smaller than the number of

have appeared in the systems of philo

poetics. Even to-day semantics is consid

of all these systems. It is still spread ou

subject matter is such that it would rem

what is important is the existence of cer

under one distinctive heading.

The Indian semantic tradition is ve

semantic tradition in the distribution of li

The Indian semantic thought is to be fo

linguistics ( vyãkarana 'grammar') but

exegesis ( Mímãmsã ), philosophy ( m

major schools and the Buddhist and the

Vai$esika) Buddhist and Jain Nyãya)

kãvya-éãstra ). The only science that is

this did not develop as a system in anci

viveka , Abhidhã-vrtti-mãtrlcã , Éabda-

éabda-Šakti-prakáéiJca and vrtti-vãrtti

study of meaning. Works like Sphota-sid

Sphota-vãda and Tattva-bindu are primar

of signification and hence with such im

role of phonemes and morphemes in

language and the Indian tradition have an

that is concerned with the study of meani

We do not, however, find any old spe

study of meaning in the Indian traditio

Sanskrit corresponding term that bas so

ntics ' ( Staal 1966 : 306 ). It can, howev

Indian tradition most probably did not

study of meaning, it did consider from

linguistic forms and the study of meaning

linguistic knowledge- intimately conne

1 Add this point to the points in section %

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

important and too extensive not to have recognition às mutually

distinct bodies of knowledge. Theoretically form and meaning are not

absolutely separable, but there is so much to be said about form and so

much about meaning that the study of form and the study of meaning

ihould form separate bodies of linguistic knowledge. That this was

the attitude of ancient Indian linguists can be gathered from the

following facts : ( i ) The Pãninlyas distinguish between the rüpa-

■ formal ' aspect of grammar and the artha - 1 semantic ' aspect of

grammar. Works like Astãdhyãyí , Mahãbhãsya , Kãéikã , Siddhãnta -

kawmudî and Šabdendu-éekhara are always distinguished from works

}ike Sangro, ha, Vâkya-padîya , Sphotasiddhi , Vaiyäkarana-bhüsana

And Vaiyäkarana-siddhänta'laghu-maftjü8ä. The latter are concerned

not only with meaning but also with what we now refer to as the philo*

Bophy of language and the philosophy of grammar ; but the emphasis is

always on the study of meaning -lexical as well as grammatical, (ii)

Panini who describes the Sanskrit language mainly through forms,

fhows awareness of many semantic notions ; but he does not make them

the laksya * subject-matter' of his work. He utilizes them only when

they pave the way to broader grammatical generalizations and hence to

increased simplicity of description. He seems to have assumed that

the semantic notions which he utilizes are the subject-matter of a

system that is different from the system of formal descriptive grammar.

( iii ) The Mirriãmsã is a very old school of Indian philosophy. It»

primary concern on the theoretical level has always been the problems

of meaning and interpretation. It has never been confused with formal

grammar. ( iv ) The Sanskrit kãvya-kãstra ' poetics ' is a linguistically

oriented system. It discusses many topics which we would now include

in semantics. Perhaps it contains the best of Indian theorizing about

meaning. Explicitly and implicitly this kãvya-sãstra borrows a number

of ideas from the grammarians and has, for this reason, been referred to

as vyãkaranasya puccham ' the tail of grammar ' It is worth noticing

that a study of meaning has been considered to be an extension of a

study that is mainly devoted to linguistic forms and has not been treat*

ed as a part of the latter. ( v ) In the kãvya-sãstra itself we find a

division of figures of speech based on the division of form and meaning.

Such a division is present even in the oldest available texts of the

system. This fact can very well be an indication of the desire for rela-

tively independent treatment of form and meaning that the ancient

Indian thinkers of language had. Thus it will be clear that in ancient

India the study of meaning was distinguished from the study of lingui-

stic forms, though the former appeared as a part of some related body

of knowledge. Works concerned purely with the problem of significa-

tion, it seems, did not appear until after Xnandavardhana ( ninth

çentury À. D. ), the author of thç Dhvanyãloka.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 2fff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 17

t. 1

Two attitudes are noticeable in some of the western studies of the

problem of meaning. Bloomfield and some of the linguists influenced by

him seem to consider any satisfactory solution of the problem of mean-

ing almost an improbability.1 Philosophers like Quine ( 1953 : 47-64 )

show the direction in which one should approach the problem of mean-

ing but do not actually tackle the problem ; instead, they try to keep

philosophical analysis clear off it if they can.2 There is nothing

wrong with one's being aware of the difficult nature of the problem one

is trying to solve. Similarly, there should not be any objection if an

investigator feels that a particular area of knowledge is a mess and

should be avoided. I would even concede that if one accepts Bloomfield's

concept of meaning, it is indeed impossible to solve the problem of mean-

ing in a way that would satisfy a scientific mind. One fact, however,

emerges clearly. A sort of defeatist attitude is implicit in the remarks

especially of Bloomfield - and it has had its effect on the western

linguistic tradition, especially in the United States ; the study of mean-

ing was neglected for some time.

This defeatist attitude does not seem to be a result of the various

notions of meaning that were then current. Nor does it seem to be a

result of the various meanings of the word 4 meaning' which are still

current. It seems to be a result of the wrong approach to the problem,

of the confusion of meaning with reference3 and of the behavioristic

trend.4 The approach was wrong in the following way. Bloomfield

i ť The statement of meaning is therefore the weak point in language-study,

and will remain bo until human knowledge advances very far beyond its present

state '.

« Since we have no way of defining most meanings and of demonstrating their

constancy...'

« Although the linguist cannot define meanings, but must appeal for this to

students of other sciences or to common knowledge...' ( Bloomfield 1933 : 140, 144,

145 ; see also 1943 ).

2 1 ... (if we are to admit such things as meanings ) ... ' ( Quine 1960 : 201 ).

Moreover, Quine ( 1953: 48 ; 1966: 200) argues in favor of replacing the word

6 meaning ' by the words ' synonymous ' and ť significant '.

• That Bloomfield has confused meaning with reference is evident from his

statements in which he expresses the view that accurate statements of meaning are

not possible without an accurate scientific knowledge of the speaker's world and

from his calling an utterance of ( apple ' etc. an instance of deviant speech when an

apple etc. are not present. See note 1 above.

4 Bloomfield's behavioristic bias is too clearly expressed in his writings and

has been too often pointed out in the studies of his thought to need any indicatory

proof. His theory of meaning is a stimulus-response theory ( Alston 1964 : 26 ).

3 [ Annals, B. O. R. I. ]

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

assumed that every word in language must have a definite meaning and

that there could be no truly scientific theory of meaning as long as we

are not able to define the meaning of each word (Kunjunni Raja 1963:4);

but as Frege ( transi. 1952 : 42 ) says, ' One cannot require that every-

thing shall be defined, any more than one can require that a chemist shall

decompose every substance or as Russell ( 1940 : 29 ) says, • It is no

more necessary to be able to say what a word means than it is for a

cricketer to know the mathematical theory of impact and projectiles '

Further, Bloomfield misses the point that semantic systems are man-

made and autonomous, that circumlocution is not a make-shift device

for stating meanings but the most effective royal road ( Weinreich

1966 : 192 ).

In the Indian tradition we find various notions of meaning

( Kunjunni Raja 1963 : 69-74, Bhartrhari 2. 119-137 BSS pp. 132-139 ).

The Sanskrit term that corresponds to English ' meaniug ', namely

' artha ', does not have exactly the same number of meanings, but defi^

nitely has enough to cause confusion.1 Occasionally, though not as

commonly as in the western tradition, we find meaning understood as

reference.2 Still there is no expression of a defeatist attitude, no trace

of having given up the problem of meaning in despair. There is a con-

founding variety of views on almost all important theoretical problems

in semantics3 and quite a few instances of both genuine and deliberate

misunderstandings and misrepresentations;4 but the pursuit of mean-

1 See the dictionaries of Sanskrit by Roth-and-Böhtlingk, Monier Williams,

Apte etc. For the meanings of c meaning', see Ogden and Richards ( 1953), Abraham

( 1963 ), Fries ( 1954 : 62-63 ) and Read ( 1955 ).

2 For example, Sabara ( 1. 1. 5 ) : ' syãc ced arthena sambandhah krura-

modaka- àabdoGGãrane mukhasya pätana-pürane syãtãm . ' ť If there were any natural

relationship between a word and its meaning, the word ' razor 1 would cut the mouth

and the word ' sweet cake ' would fill it '. This statement is a part of the argument

to which Sabara does not subscribe. It is based on a wrong under*

standing of the Mtmãmsã position on the part of Sahara's philosophical advers

When the Mimãmsakas say 1 aulpattikas tu šabdasyarthena sambandhah ' they just

wish to point out that it cannot be told when exactly the relation between word

and meaning came to be established. The Mimãmsã doctrine of autpattika éabdã-

řtha-sambandha and the Vyãkarana doctrine of nitya or anãdi-siddha éabdõrtha -

sambandha are essentially the same ( see Bhartrharťs vrt ti on 1. 23, p. 59 ).

3 Even a perusal of the books by Kunjunni Raja and Bhattacharya would

convince one of this point.

4 For example, Kumarila's arguments against the grammarian's view of

indivisible sentence meaning. They seem to be a result of confusion of meaning

with reference -at least as far as Bhattacharya's ( 1962: 33-37 ) exposition

of them goes. It is not uncommon to find in Indian philosophical texts that that

interpretation of a philosophical adversary's theory is chosen which can be best

attacked. Interest in polemics and tendency of treating philosophical discussions as

a game for sharpening one's wits cannot be said to be entirely absent in the Indian

tradition, Bee note 2 above.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 19

ing in all its aspects continues -undetered a

of detail. This is particularly true of th

discussed a number of individual cases from

meaning till very recent times.

S. «

The immensity of the problem of meaning, the chaos of termino-

logy, aversion for anything that smacked of mentalism1 and perhaps a

¡confusion of meaning with reference2 led some of the linguists in the

American branch of western linguistics to think of excluding meaning

from linguistic analysis. It should not be supposed that such an

exclusion was actually achieved or was theoretically justified to such

an extent as to convince every contemporary American linguist of its

correctness. Nor should Bloomfield be considered to be an advocate

of this exclusion of meaning ( Fries 1954 : 57-60, 1962 : 212-216 ). On

should also be careful about what one exactly means by 'linguist

analysis'; in the discussion of this point it should include only t

discovery procedure and not the description procedure ; for, most of th

linguists of any tradition would agree that considerations of mean

should not dominate grammatical description and nothing would b

distinctive about the efforts of Bloch ( 1948 : fn. 8 ) and Harris (1952 : 1

1954 : 39-42 ) if they insisted only on this principle of linguistic descrip

tion. As Fries ( 1962 : 216 ) has observed :

' A number of American linguists... who have been considerably

influenced by Bloomfield, have tried to go beyond him in the exclus

of meaning - at least they have proposed, as a theoretical possibilit

the total exclusion of the use of meaning in analysis. No examples

descriptive analysis accomplished on this basis have appeared '

In the Indian linguistic tradition we do not find any instances o

linguistic analysis achieved without the use of meaning. We do n

even notice any trend in this direction. In theory we always fi

meaning given the status of a basis for determining the phonemes

morphemes, grammatical categories etc. Anvaya-vyatireka , finding

distinctive features of linguistic expressions through binary oppositi

is an age-old method in India. The grammarian or the linguist proce

to apply it in the following way : ( i ) The meaning of a linguis

1 Katz ( 1964 : 124-137 ) discusses the type of mentalism that is harmful to

true science and points out how the Bloomfieldian attack on mentalism was

misdirected.

2 Bar-Hillel ( 1954 : 203-237 ) does not exactly hold that confusion of mean-

ing and reference led linguists to think of excluding meaning from linguistic

analysis ; according to him, it led linguists to disregard meaning - the linguists

thought that questions of reference ( truth etc. ) do not fall within linguistics.

Quine ( 1953 : 47 ) is of the opinion that confusion of meaning with reference had

encouraged a tendency to take meaning for granted.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 Annals of the Bhandarhar Oriental Research Institute

expression as the native speaker understands it, is never to be ques-

tioned.1 ( ii ) If there is an expression ( usually a sentence or a com-

pound) of the form * x y ... ' with a meaning of its own and 1 x 1 y ' •••

are accepted as possessors of meaning in themselves, then ťx', ťy'..«

are the pada units of the language.2 The linguist uses the technique

of checking the changes in meaning with the presence and absence of

what he postulates to be a pada* Such pada-apoddhãra * picking up

of the padas ' is frequently done by the speakers of the language on the

level of communication. The linguist who is not using the language

but studying it and for whom the level is that of analysis, however, goes

a step further than a speaker of the language in his capacity as a

speaker goes.4 ( iii ) He studies the various situations in which the

padas occur, notes the relations in which they stand to each other and

tests if some elements in the padas can be linked to the relations in a

systematic way. If he finds a system of relations and of formal ele-

ments in the padas , he accepts the elements as linguistic units, for the

relations they regularly express are associated with them as meanings

are with the padas . The elements are the pratyayas and the remain-

ing parts of the padas are the prakrtis .5 This is prakrti-pratyaya -

1 In the following places, Helãrãja, the author of the Prakirnaka-prakã&i I,

makes it clear that grammatical rules do not invest expressions with meanings

but that they merely follow the meanings of expressions as understood in the

linguistic community : 3. 7. 61 ; 3. 8. 2 ; 3. 9. 100, 110 ; 3. 10. 8 ; 3. 13. 12, 31 ; 3. 14, 33,

42, 53, 119, 154, 155, 192, 193, 194, 308, 408, 413, 547, 584.

2 ť artha-dvãrena ca pada-pariksã. - Helãrãja, 3. 1. 2, p. 10 ; * tad evam art ha -

dvãrena pade pariksyamãtie...1 - Helãrãja, 3. 1. 48, p. 57. 6 tatrãpoddhãra-padãrthah

... anvaya-vyatirekãbhyãm riipa-samanugama-kalpanayã Samudãyãd apoddhrtãnãm

áabdãnãm abhidheyatvenãériyate . ' vrtti 1. 24-26, p. 65.

3 * anvaya-vyatirekãbhyãm hi viêiçtãrtha-êabdãvadhãranam. ' - Helãrãja,

3.1.87, p. 8 5 6 yathãrtham parikalpitãnvaya-vyatireka-nibandhano vãkgavãdinâm

padãpoddhãrah . Helãrãja, 3. 1. 1, p. 2.

* It should be noted that the prakrti-pratyaya-apoddhãra is called ' êãatriya ' :

»... sãstrlyãnvaya - vyatireka - nimittãrthãpoddhãra - vašah prakrti - pratyayãdya -

poddhãrah - Helãrãja, 3. 1. 1, p. 2 ; 6 yathaiva vãkyãt padãrtha-pravibhãgena

vy avahãr ah kriyate , tathã padãd api prakrti-pratyayãdyapoddhãrena êãstre bhüyän

vyavahãro dréyate .' - vrtti 2. 164-165. Some instances of pada-apoddhãra in ordinary

life and in contexts other than that of the discovery procedure, are noted in

Trikãndi 2. 72-87.

5 * èiddham tvanvaya-vyatirekãbhyãm. ... iha vrkça ityukte kaicicchabdah srüyate ,

Vrksa-ûabdo 5 kãrãntah sakãras ca pratyayaht artho'pi kaécid gamy ate. ... vrkçãv

ity ukte kašctcchabdo hiyate , kaécid upajãyate , kaécid anvayi . ... ekatvam hiyate ,

dvitvam upajãyate , mula - skandha-phala - palãsa-vãn anvayi . te manyãmahe yah

éabdo hiyate tasyãsãv artho yo Wtho hiyate , yah kabda upajãyate tasyãsãv artho yo *

rtha upajãyate , yah êabdo'nvayi tasyUsãv artho yo'nvayi. 1 - Patañjali, 1. 2. 45.

Vol. I p. 21Ô. See also 1. 3. 1. 6, Vol. I p. 255 ; 1. 3. 1. 5, 6, Vol. I p. 255; and the

remarks quoted in footnote 4 above.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 21

apoddhãra. ( iv ) The anvaya-vyatireka tes

prakrtis also. The linguist finds that the pra

convey the meaning that is associated with th

out from them, if they are wholly or partly pr

deviant way or if some new element is introd

realises that the elements that go into the ma

role in the conveying of meaning even though

with them as individual entities.2 He accep

units of language, varnas, thus again using

vyatireka of meaning. In this way meanin

discovery procedures in the Indian tradition

the theory of linguistic analysis. There have b

meaning from linguistic analysis though, as

Indian grammatical tradition knows, there ha

on meaning in the available linguistic descrip

is thus essentially the position taken by Fries ( 1954 : 60 cp.

1962 : 215 ) :

'... on all levels of linguistic analysis certain features and types

of meaning furnish a necessary portion of the apparatus used... I do not

mean to defend the common uses of meaning as the BASIS of analysis

and classification, or as determining the content of linguistic definition

and descriptive statement. ... The issue is not an opposition between

NO use of meaning whatever, and ANY and ALL uses of meaning

0. S

A natural consequence of the tendency in the West toward gett-

ing rid of meaning in linguistic analysis and of the oft-repeated point

that meanigs are mental entities of some kind was the feeling that

semantics does not legitimately belong to the field of linguistics, that it

should better be included in some other branch of knowledge, say,

psychology or the science of signs. The very first sentence of Garvin's

article in 1958 contains the explicit phrase, the oft-repeated position

that we cannot handle meaning linguistically../; one of Voegelin's arti-

cles ( 1949 ) is significantly titled as ' Linguistics without meaning and

culture without words ' ; in a recent article ( 1967 ) McCawley starts

with the comment that semantics is considered to be a nebulous area in

transformational grammars and concludes that ' ... it is high time for

1 See Patañjali's discussion ( on Pratyãhãra-sãtra 5, vol. I pp. 30-32 ) of the

following vãrttilcas : e varna-vyatyaye cãrthãntara-gamanãt ' varnãnupalabdhau

cãnartha-gateh ' and i varna-vyatyayãpãyopajana-vikuresvartha-darêanãt '.

2 ' ... manyãmahe ' narthakã varnã iti , - Patañjali, Pratyähära-sütra 5, vol, I

p. 31 ; ' sãstrãrtha èva varnãnãm arthavattve gradar hit ali 6 yathaivãnarthahaif

varnair ... ' - Trikãndi 2. 210, 410.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22 Annals of the Bhanctartcar Oriental Research Institute

linguists to grant to semantics the status as an integral part of lingui-

stics which has hitherto been denied to it by most ' ; in his survey of the

glossematic school of linguistics Spang-Hanssen ( 1962 : 132, 135 ) takes

pain to establish that glossematics does not exclude semantics.

This type of situation did not arise in India. There semantic

thought was always a prime concern of all the systems that were

concerned with language. This is perhaps partly due to the fact that

psychology, especially that of the behavioristic type, did not develop in

India and partly to the fact that the Indian thinkers of language were

never bogged down by the problem of meaning ; they never considered

it to be a ' nebulous ' area, which, in turn, is due to the fact that a

correct approach ( see para. 2 under 2. 1 above ) to the problem of

meaning was taken from very early times in India.

2.4

In the western tradition semantics has been usually thought of as

à part of the general science of signs. Saussure's ( 1916 : 33 ) term for

the latter is ' semiologie ' while later writers generally prefer the term

• semiotics ' Peirce's writings have proved to be a great impetus for the

development of semiotics in the West. He divides semiotic theory into

pure grammar, logic proper and pure rhetoric ( pp. 135-136 ) and he

divides signs from three points of view ( pp. 142-146 ), the most im-

portant division being the one into icons, indices and symbols. Morris

(1938, 1946 ) carried further Peirce's point of view and made significant

contributions in terms of scope of semiotic discussions, variety of the

view-points adopted in studying the operations of signs and the terminò-

logy of semiotics. His division of semiotic theory into syntactics,

semantics and pragmatics ( 1938 : 84-85 ) is especially note-worthy.

Roughly in the first quarter of this century ( 1923-29 ) were published

the three volumes of Cassirer's Philosophie der symbolischen Formen

among which the first volume is about Die Sprache . He discusses in

detail language as a system of signs and analyses the relations between

things and concepts on the one hand and linguistic expressions on the

other. Among present day linguists, Harris ( 1954 : 38 ) has expressed

the view that meaning is not a unique property of language, Guiraud

( 1955 : first chapter, pp. 84-99 ) has distinguished between signs and

šymbols, and Weinreich ( to be published ) has discussed semantics and

semiotics'. Thus in the West the science of meaning is closely associated

with the science of signs and attempts have been made for the

development of both.

The Indian tradition greatly differs from the western tradition in

this respect. There is reason to believe that non-linguistic ( or, only

apparently non-linguistic ) systems of signs like gesture languages,

secret code languages, were developed and were current in India frpm

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 23

considerably old times ; 1 it is well-known

grammar that creation of artificial langu

terms, the krtrima samjftäs,2 was not a

even find discussions about the meani

laukika sañijñás* about the Mïmâmsâ the

a word and its meaning is svãbhãtika

theory that such a relation is sãnketika '

distinction between sign and symbol h

Still, the general science of signs is not

India. Nor do I find any piece of evidence

ceived as a frame-work of the science of m

It is likely that the Indian thinkers

language is the basic system of signs -th

systems of signs have as their basis som

In other words, it could have been their

non-linguistic systems of signs are const

language, that their nature is determined

that conceives of them and that they ar

language whether consciously or unconsc

e. e

As Ullmann (1964 : 9 ) observes, stylistics has had a profound

influence on semantic studies in the West. In the Indian tradition we

do not find any distinctive body of literature that could resemble modern

ptylistics. There are however quite a number of ideas and observations

scattered through the system of Sanskrit poetics that modern stylistics

could profitably use. For that aspect of stylistics which is concerned

with the expressive values of language, the discussion of alankãrat

' figures of speech ' in the Sanskrit tradition would prove to be %

treasure of remarkable insights ; for that other aspect of stylistics which

1 According to Sukumar Sen ( 1968 : 681 ), Mfiladevïya , a kind of cryptic or

concealed language is quoted in the Jaya-matigala, a commentary on the Kama -

miras. See also Kautilya 1. 12. 11, 13 ; 1. 16. 25 ; Bhãsa Pratijftã-yaugandharãyana

act 3 ; Bharati ( 1965 : 164-184 ). One comes across a number of artificial technical

terms in Sanskrit works on grammar, mathematics, astronomy and astrology.

The Tantra and Yoga works use many common words as symbols having specifio

significance in the framework of the system.

2 Standard illustrations of the krtrima samjftãs are ti, ghu , bha etc.

3 Trikãndi 2. 365-371. See also the metarule ' krtrimãkrtrimayoh krtrimt

kãrya-sampratyayah ' in the Mahãbhãsya and the Paribhãsã works.

* Ruegg ( 1959 : 12, 72-73 ), Kunjunni Raja ( 1963 : 19-23 ) : vrtti 1. 23, p. 59;

1. 24-26, p. 71.

5 ' akçi-nikocãdinãm api éabdenaivãnumãpakatvafh , sanketitatvãt, ' - Helãrãja,

3, 14. 197, p. 96. See also vrtti 1. 24-26, p. 72 ; 1. 141, p. 230 ; 1. 147, p. 235,

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 Annals of the BhandarJcar Oriental Research Institute

is concerned with the emotive values of language, the Sanskrit dis-

cussions about the gunas * qualities of the poetic sentiment ', about the

relation between the sounds a literary composition uses and the mood it

tries to create, about ancitya ' literary propriety about the different

ways in which the nature of literary suggestion is affected, and about

the vyabhicãri-sancãri bhãvas ' the fleeting moods that a poet describes

to make manifest the culminating mood ' may prove to be significant.

The Sanskrit literature thus contains some ingredients of a general

theory of stylistics. It does not however contain any studies of the

styles of individuals or of styles used in different literary forms in

different social contexts ( e. g. styles in folk literature ) as the western

literature contains. Thus in a sense the Indian tradition has a stylistics

of its own and in a sense it does not have it. Under either alternative

one does not meet a situation in which semantics is aided or influenced

by stylistics.

m

One cause of the Indian tradition's being different in this respect

from the western tradition is of course the absence of stylistics as a disti •

nctive branch of knowledge in India ; had it been a distinctive branch it

would have most probably iufluenced Indian semantics, for, both these

fields of intellectual activity are too close to each other to avoid mutual

influence. One could also argue that the Indian theorizing about lite-

rary style did in fact influence the Indian theorizing about meaning,

only we do not have any way open to us for examining this influence

because the theorizing about style did not develop into a distinctive

system. The question then, which would take us to a deeper analy-

sis of circumstances, is, ' Why did not theorizing about style develop

into a distinctive branch of knowledge in India ? ' As all histo-

rians of thought know, it is very difficult to answer such questions in

any definite or exact way. My own guess would be as follows. In the

western tradition where poetics was mostly speculative and individuali-

stic in its approach, not especially keen to use the basis of linguistics

until very recent times, stylistics which uses the relatively objective

basis of linguistic expression ina rigorously or semi-rigorous ly stati-

stical way, was, so to say, a historically necessary intermediary

science. Indian poetics, especially after Snandavardhana ( ninth century

A. D. ), was, on the other hand, an exquisite edifice built on a solid

ground of Indian linguistic thought with room left for changes only

through logic and not through speculation or individual preferences.

Therefore there were 110 forces in India which could lead to the emer-

gence of an intermediary branch of study approximating western styli-

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 25

sties. Another possible cause is the absenc

does not seem to have occurred to the Ind

a single literary work or an individual au

could be studied by preparing a statistica

tendencies.

S. 6

No attempt for the statistical measurement of meaning, like the

one which we find in the writings of Osgood and others (1957 ), was

ever made in the Indian tradition. Absence of statistics as a science,

lack of electronic machinery etc. are of course the obvious causes of not

having made such an attempt. It is an interesting question whether

the Indians would have engaged themselves in a similar experiment had

the statistical and computing techniques been available to them. I

think that as psychologists or as compilers of thesauruses they would

have been interested in experiments like that of Osgood's, for, these

experiments do bring out a kind of average of a community's emotive

connotations with various words ; but as theoreticians of meaning they

would not have made much of these experiments. They seem to be of

the opinion that a roughly available consensus of the speakers of a

language is sufficient for the purposes of analysis and theoretical descri-

ption of meaning.1

2. 7

Most of the early studies of meaning in the West were studies in

historical semantics. Thinkers interested in language and meaning

classified and characterized various changes of meaning and tried to ex-

plain their causes. Very few were interested in answering the question

what meaning is ( Malmberg 1964 : 125 ). Asa result we have a very

rich tradition of historical semantics in the West.

The Indian semanticists have, however, paid very little attention

to the problem of change of meaning. They have studied it from a

synchronic point of view ; that is, they have probed the phenomenon of

change in meaning with changing contexts and this they have done with

remarkable thoroughness, but the studies of change in meaning from a

dichronistic point of view are almost entirely lacking in the Indian

tradition. The Indian observations in this respect do not go beyond

recording the phenomenon of nirüdha-laksanä ' stabilization of an

originally secondary meaning ' ( Kunjunni Raja ( 1957 : 127-130, 1963 : 10

38-47, 59-69).

1 4 kiñeit sãmãnyam ãéritya sthite tu pratipãdanam ' Trihãndi 3. 10. 8cd.

* sãdrèya-leéãnugama-mãtrena tu éabdãnuêãsane yathã- Icathañcid artho nirdiéyate...9-

Helãrãja, 3. 14. 202, p. 98. See also Helãrãja, 3. 10. 8, p. 101 ; 3f 14. 192. p. 95t

4 [ Annals, B, O. R. I. ]

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26 Annals of the BhandarJcar Oriental Research Institute

This fact is rather surprising. From very old times the Indians

were aware of the change that had taken place in the Sanskrit language.

Efforts to determine the meanings and etymologies of Vedic words had

begun even before Yãska. The prãtiéãkhyas had noted the changes in

pronunciation with great zeal. The grammarians had brought to atten-

tion the changes in forms. The writers of Prakrit grammars had

essentially used the technique of postulating a common form when they

treated Sanskrit forms as prakrti ' the original ' and Prãkrta forms as

vikrti 1 the derivative ' of Sanskrit forms. The phenomenon of nirüdha-

laksanã had been noticed. Homonyms and homophones had attracted

the attention of all thinkers interested in language (Kunjunni Raja

1963 : 34-48 ). Still, nothing that would resemble the western histori-

cal semantics developed in India.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abraham, Leo. 1936. " What is the theory of meaning about ?"

The Monist , 46. 228-256.

Alston, William P. 1964. Philosophy of language . Prentic

Foundations of Philosophy Series. Englewood Cliffs,

Jersy.

Arjunwadkar, Krishna Shrinivas and Arvind Mangrulkar. ( eds. and

transi. ) 1962. Mammata-bhatta-vir acita Kãvya-prakãia.

Poona. ( Marathï ).

Bar-Hillel, Y. 1954. " Logical syntax and semantics Language , 30.

230-237.

Bharati, Agehananda. 1965. The Tantric tradition. London.

Bhartrhari. Vâkyapadïya or Trikândï.

( a ) kãnda I. ( ed. ) Subramania Iyer. K. A. Deccan College

Monograph Series no. 32. Poona 1966.

( b ) kãnda II. kãrikã. ( eds. ) Abhyankar K. V. and Y. P.

Limaye. University of Poona, Sankrit and Prakrit Series

no. 2. Poona 1965.

vrtti . ( ed. ) Charudeva Shastri. Ramlal Kapoor Trust

Society, Lahore, Around 1941.

( c) kãnda III. samuddeèas 1-7. (ed. ) Subramania Iyer. K.

Deccan College Monograph Series no. 21. Poona 1963.

samuddeias 8-13. (ed. ) Sãmbaáiva Castri, K. Trivan

drum Sanskrit Series no. CXVI. Tri vandrům 1935.

samuddeša 14. (ed. ) Ravi Varmã, L. A. University of

Travancore Sanskrit Series no, CXLVIII. Trivandrum

1942t

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 2 7

Bhäsa. Bhãsa-nãtaJca-cakram. ( ed. ) Devadhar, C. R

Series no. 54. Poona 1937.

Bhattacharya, Bishnupada. 1962. A study in language and meaning

Calcutta.

Biardeau, M. 1964. Theorie de la connaissance et philosophie de la

parole dans le brahmanisme classique. Paris.

Bloch, Bernard. 1948. "A set of postulates for phonemic analysis".

Language. 24. 3-46.

Bloomfield, L. 1933. Language. New York.

35. 101-106.

Chakravarti, P. C. 1930. The philosophy of Sanskrit grammar. Univer

sity of Calcutta, Calcutta.

..

sity of Calcutta, Calcutta.

Frege, Gottlob. Translations from the

(eds. ) Peter Geach and Max Black.

Fries, Charles C. 1954. "Meaning and L

30. 57-68.

and American linguistics . 193

mann, Alf Sommerfelt and Jo

Mass.

Garvin, Paul L. 1958. " A descriptive technique for the treatment of

meaning Language , 34. 1-32.

Gaurinath Sastri. 1959. The philosophy of word and meaning . Calcutta

Sanskrit College Research Series no. 5. Calcutta.

Guiraud, Pierre. 1955. La sémantique. Paris.

Harris, Zellig S. 1952. "Discourse analysis". Language , 28. 1-30.

age. (eds. ) Jerry A. Fodor and

Cliffs, New Jersy. 1965. Reprint.

Heläräja. See Bhartrhari ( c ).

Joos, Martin. 1958. " Semology : a

Studies in linguistics , 13. 53-70.

Katz, Jerrold J. 1964. " Mentalism

124-137.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

28 Annals of the ßhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

K^utilya. Artha-éãstra. (ed.) Kangle, R. P. University of Bomba#

Studies in Sanskrit, Prakrit and Pali, no. 1. Bombay 1960.

Kronasser, Heinz. Handbuch der Semasiologie .

Ku nj unni Baja, K. 1957. " Diachronistic linguistics in ancient India.1'

Journal of the Madras University , pp. 127-130.

Series no. 91. Madras.

Malmberg, Bertil. 1964. New trends in linguistics : an orientation .

Translated from the Swedish original by Edward Carney.

Stockholm Lund.

McCawley, James D. 1967. "How to find semantic universais in the

event that there are any." Read in mimeographed form.

Morris, Charles W. 1938. " Foundations of the theory of signs. "ú'

International Encyclopaedia of Unified Science, (eds. ) Otto

Neurath, Rudolf Carnap and Charles Morris. Vol. I, pp. 76-137.

Chicago.

Ogden, C. K. and I. A. Richards. 1923

The meaning of meaning. New

Osgood, Charles E., Q. J. Suci and

printing 1961. The measurement

Pandeya, R. C. 1963. The problem

Delhi.

Patañjali. Vyãkarana-mahãbhãsya. ( ed. ) Kielhorn, F. Third edn.

Vol. I. Poona 1962.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. Collected Papers Yol. II. (eds. ) Charles Hart-

shorne and Paul Weiss. Harvard University Press. Cambridge,

Mass. 1960.

Quine, Willard van Orman. 1953. From a logical point of view. Harvard

University Press. Cambridge, Mass.

Mass.

Read, Allen Walker. 1948. " An accou

4. 76-97.

' meaning 6th RTMf pp. 123-13

Ruegg, David Seyfort. 1959. Contr

sophie linguistique indienne . Par

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient Indian Semantics 29

Russell, Bertrand. 1940. An inquiry into me

Šabara. Mimäfosä-sütra-bhäsya. Anandãáram

Poona 1929.

Saussure, F. de. 1916. Cours de Linguistique Générale. Lausanne.

Spang-Hanssen, Henning. 1962. " Glossematics ". Trends in Euro -

pean and American linguistics : 1930-1960. (eds. ) Christine

Mohrmann, Alf Sommerfelt and Joshua Whatmough.

Staal, J. F. 19tj0. "Review of Ruegg (1959)." Philosophy East and

West. 10. 53-57.

ental Society , 86. 304-311.

Sukumar Sen. 1968. " On Müradeva M

d'Indianisme a la mémoire de Lou

Trikândï. See Bhartrhari.

Ullmann, Stephen. 1962-1964. Semantics. New York.

Greenberg, J. H. The M. I. T. Press

C. F. 1949. " Linguistics without m

words." Word , 5. 36-42.

vrtti. See Bhartrhari ( a ) and ( b

Weinreich. Uriel. 1966. " On the sem

Universais of language (ed. ) Green

Press. Cambridge. Mass.

Encyclopaedia of the Soc

shed by Crowell-Collier.

This content downloaded from

128.171.57.189 on Sun, 27 Feb 2022 01:43:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- A History of Indian Philosophy, Volume 1From EverandA History of Indian Philosophy, Volume 1Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Buddhist Philosophy of Language in India: Jñanasrimitra on ExclusionFrom EverandBuddhist Philosophy of Language in India: Jñanasrimitra on ExclusionNo ratings yet

- Can The Grammarians'Dharma Be A Dharma For All JIP2004Document46 pagesCan The Grammarians'Dharma Be A Dharma For All JIP2004forizslNo ratings yet

- Potter 1957Document5 pagesPotter 1957adeeba.aliNo ratings yet

- Context of Ancient Indian PhilosophersDocument17 pagesContext of Ancient Indian PhilosophersPmsakda HemthepNo ratings yet

- 1 Observations On Language Spread in Multi-Lingual Societies-2 (1) Sujay Rao MandavilliDocument73 pages1 Observations On Language Spread in Multi-Lingual Societies-2 (1) Sujay Rao MandavilliSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Subhāṣita Saṃgraha-S in Old-Javanese and Tibetan (Ludwik Sternbach)Document45 pagesSanskrit Subhāṣita Saṃgraha-S in Old-Javanese and Tibetan (Ludwik Sternbach)Qian CaoNo ratings yet

- Daya Krishna - Indian PhilosophyDocument220 pagesDaya Krishna - Indian PhilosophySanPozza100% (1)

- Panel Proposal for Group Section on Comparative Literature at ICLA Conference 2013Document9 pagesPanel Proposal for Group Section on Comparative Literature at ICLA Conference 2013Judhajit SarkarNo ratings yet

- A Source Book in Indian PhilosophyFrom EverandA Source Book in Indian PhilosophyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy - John GrimesDocument400 pagesConcise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy - John Grimesmvinkler50% (2)

- D'Ottavi - Ferdinand de Saussure Et L'Inde - Contacts Et Consonances ThéoriquesDocument13 pagesD'Ottavi - Ferdinand de Saussure Et L'Inde - Contacts Et Consonances ThéoriquesEric M GurevitchNo ratings yet

- Thesis SanskritDocument4 pagesThesis SanskritPaperWritingServicesForCollegeStudentsSingapore100% (2)

- The Purusha Suktam: An A-Religious Inquiry into a Sacred TextFrom EverandThe Purusha Suktam: An A-Religious Inquiry into a Sacred TextNo ratings yet

- 200002-02 - Ancient and Modern ScienceDocument8 pages200002-02 - Ancient and Modern SciencemanoharlalkalraNo ratings yet

- Traditional and Modern Sanskrit Scholarship: How Do They Relate To Each Other?Document14 pagesTraditional and Modern Sanskrit Scholarship: How Do They Relate To Each Other?Pmsakda HemthepNo ratings yet

- Vāda in Theory and Practice: Studies in Debates, Dialogues and Discussions in Indian Intellectual DiscoursesFrom EverandVāda in Theory and Practice: Studies in Debates, Dialogues and Discussions in Indian Intellectual DiscoursesNo ratings yet

- A Concise Dictionary of Indian PhilosophyDocument400 pagesA Concise Dictionary of Indian PhilosophyEl Zorro100% (2)

- J CH Chatterji - Hindu Realism 1912Document218 pagesJ CH Chatterji - Hindu Realism 1912ahnes11No ratings yet

- Unity in Diversity - India and Western Philosophical Tradition (2005)Document19 pagesUnity in Diversity - India and Western Philosophical Tradition (2005)Đoàn DuyNo ratings yet

- Kahrs - Indian Semantic Analysis The Nirvacana Tradition - Kashmir - SaivismDocument318 pagesKahrs - Indian Semantic Analysis The Nirvacana Tradition - Kashmir - SaivismRalphNo ratings yet

- Sociocultural PraxisDocument14 pagesSociocultural PraxisPratap Kumar DashNo ratings yet

- Sabda_Sakti_Power_of_Words_in_Indias_LinDocument20 pagesSabda_Sakti_Power_of_Words_in_Indias_LinyaqubaliyevafidanNo ratings yet

- Presidential AddressDocument10 pagesPresidential AddresshannahjiNo ratings yet

- Sabda Sakti KalakalpaDocument17 pagesSabda Sakti Kalakalpasunil sondhiNo ratings yet

- Vac. The Concept of The Word in Selected Hindu Tantras. (A.padoux) (SUNY, 1990)Document464 pagesVac. The Concept of The Word in Selected Hindu Tantras. (A.padoux) (SUNY, 1990)chetanpandey100% (7)

- UntitledDocument558 pagesUntitledakshatNo ratings yet

- Dasgupta S - History of Indian Philosophy PDFDocument982 pagesDasgupta S - History of Indian Philosophy PDFVildana Selimovic100% (1)

- Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Annals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research InstituteDocument3 pagesBhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Annals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institutekhadesakshi55No ratings yet

- Tracing The Roots of Research From Indian Perspective: June 2014Document17 pagesTracing The Roots of Research From Indian Perspective: June 2014salvatoreNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit SyntaxDocument552 pagesSanskrit Syntaxpatel_musicmsncomNo ratings yet

- A Review of Indian Buddhism by A K WardeDocument9 pagesA Review of Indian Buddhism by A K WardeZp magikNo ratings yet

- PHD Sanskrit ThesisDocument4 pagesPHD Sanskrit Thesismoniquedaviswashington100% (2)

- Bailey Pravrti-NivrtiDocument20 pagesBailey Pravrti-NivrtialastierNo ratings yet

- A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy Sanskrit Terms Defined in EnglishDocument400 pagesA Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy Sanskrit Terms Defined in Englishelenacretoiu100% (1)

- Bhate and KakDocument17 pagesBhate and KakratNo ratings yet

- SD 2Document640 pagesSD 2pabitra100% (1)

- A History of Indian Philosophy - 1 - DasguptaDocument546 pagesA History of Indian Philosophy - 1 - Dasguptaadiyanshah100% (2)

- A History of Indian Philosophy Volume IDocument2,517 pagesA History of Indian Philosophy Volume INinaBudziszewska100% (2)

- Examples of The Influence of Sanskrit Grammar On Indian Philosophy - Raffaele TorellaDocument14 pagesExamples of The Influence of Sanskrit Grammar On Indian Philosophy - Raffaele TorellaraffaeletorellaNo ratings yet

- Matilal's Insightful Approach to Understanding Indian PhilosophyDocument11 pagesMatilal's Insightful Approach to Understanding Indian Philosophypatel_musicmsncomNo ratings yet

- Sciencedirect: Contrastive Studies On ProverbsDocument4 pagesSciencedirect: Contrastive Studies On ProverbsFhaijahNo ratings yet

- AklujkarAshok The Early History Sanskrit Supreme LanguageDocument33 pagesAklujkarAshok The Early History Sanskrit Supreme LanguageAshay NaikNo ratings yet

- Sabda Brahma: Science and Spirit of Language in Indian CultureDocument21 pagesSabda Brahma: Science and Spirit of Language in Indian Culturesunil sondhiNo ratings yet

- Students Handbookof Indian AestheticsDocument138 pagesStudents Handbookof Indian AestheticsSumathi N100% (1)

- Invitation and Theme of The SeminarDocument3 pagesInvitation and Theme of The SeminarNagaraj BhatNo ratings yet

- Language Vs Grammatical Tradition in Ancient IndiaDocument35 pagesLanguage Vs Grammatical Tradition in Ancient IndiayaqubaliyevafidanNo ratings yet

- "Semantics" in The Sanskrit Tradition "On The Eve of Colonialism"Document14 pages"Semantics" in The Sanskrit Tradition "On The Eve of Colonialism"margheritatrNo ratings yet

- Indian Approach To LogicDocument24 pagesIndian Approach To LogicYoungil KimNo ratings yet

- Learn Sanskrit through its scientific principles and massive yet precise textsDocument6 pagesLearn Sanskrit through its scientific principles and massive yet precise textsprometheusrising1970No ratings yet

- 10 2307@41426852 PDFDocument7 pages10 2307@41426852 PDFabdul basithNo ratings yet

- Udayanacarya, «Atma Tattva Viveka» («Η διάκριση της πραγματικότητας του Εαυτού»)Document601 pagesUdayanacarya, «Atma Tattva Viveka» («Η διάκριση της πραγματικότητας του Εαυτού»)Dalek CaanNo ratings yet

- Room at The Top in Sanskrit PDFDocument34 pagesRoom at The Top in Sanskrit PDFcha072No ratings yet

- ISAACSON - 2009 A Collection of Hevajrasaadhanas and Related WorksDocument51 pagesISAACSON - 2009 A Collection of Hevajrasaadhanas and Related WorksMarco PassavantiNo ratings yet

- A History of Indian Philosophy - 3 - Dasgupta PDFDocument628 pagesA History of Indian Philosophy - 3 - Dasgupta PDFnicoarias6100% (2)

- Hindi LiteratureDocument7 pagesHindi LiteratureParulNo ratings yet

- Deccan College BooksDocument6 pagesDeccan College BooksmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Dhvani PosterDocument1 pageDhvani PostermkmartandNo ratings yet

- Rare Indian textsDocument1 pageRare Indian textsmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Ātmecchaṃ Pūrayet PātraṃDocument6 pagesĀtmecchaṃ Pūrayet PātraṃmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Reflection PDFDocument1 pageDynamics of Reflection PDFmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Arrivederci Napoli ! - CASHMERIAN SANSCRITISTDocument7 pagesArrivederci Napoli ! - CASHMERIAN SANSCRITISTmkmartandNo ratings yet

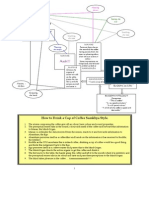

- Aaah!!!: How To Drink A Cup of Coffee Samkhya StyleDocument1 pageAaah!!!: How To Drink A Cup of Coffee Samkhya StylemkmartandNo ratings yet

- Flyer IPSummerDocument1 pageFlyer IPSummermkmartandNo ratings yet

- Deccan College BooksDocument6 pagesDeccan College BooksmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Prabuddha Bharata, June 2005 PDFDocument3 pagesPrabuddha Bharata, June 2005 PDFmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Abdul Ahad AzadDocument43 pagesAbdul Ahad AzadmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Deccan College BooksDocument8 pagesDeccan College BooksmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Purushasukta With Sayanabhashya - GB Kale 1952 Andashrama Series Printed in Pune.Document18 pagesPurushasukta With Sayanabhashya - GB Kale 1952 Andashrama Series Printed in Pune.Prathap VimarshaNo ratings yet

- KṛṣṇāvatāralīlāDocument268 pagesKṛṣṇāvatāralīlāmkmartandNo ratings yet

- UrduxDocument18 pagesUrduxmkmartand100% (2)

- Ghani KashmiriDocument202 pagesGhani KashmirimkmartandNo ratings yet

- ASS 005 Isavasya Upanishad With SKT Commentaries - Rajaram Sastri Bodas 1905Document81 pagesASS 005 Isavasya Upanishad With SKT Commentaries - Rajaram Sastri Bodas 1905mkmartandNo ratings yet

- PersianDocument92 pagesPersianMujeeb Ur Rahman100% (3)

- Linguistic Traditions of Kashmir ReviewDocument4 pagesLinguistic Traditions of Kashmir ReviewmkmartandNo ratings yet

- S Vac Chanda Tantra 6Document284 pagesS Vac Chanda Tantra 6mkmartandNo ratings yet

- Maharajaofkashmi00basuuoft BWDocument196 pagesMaharajaofkashmi00basuuoft BWmkmartandNo ratings yet

- Gurunāthaparāmarśa (KSTS)Document13 pagesGurunāthaparāmarśa (KSTS)mkmartandNo ratings yet

- The Allure of Travel Writing - Travel - SmithsonianDocument2 pagesThe Allure of Travel Writing - Travel - SmithsonianJINSHAD ALI K P0% (1)

- Englishtshiasant 00 EvanialaDocument272 pagesEnglishtshiasant 00 EvanialaGarvey LivesNo ratings yet

- Adaptation As A Process of Social ChangeDocument9 pagesAdaptation As A Process of Social ChangeArnav Jammy BishnoiNo ratings yet

- Interpretation: Resolved Denotes A Proposal To Be Enacted by LawDocument9 pagesInterpretation: Resolved Denotes A Proposal To Be Enacted by LawBenjamin CortezNo ratings yet

- Business Research Methods Solved Mcqs Set 1Document7 pagesBusiness Research Methods Solved Mcqs Set 1yohannes retaNo ratings yet

- EHI-07 BHIE-107 2018-19 EnglishDocument4 pagesEHI-07 BHIE-107 2018-19 EnglishHarsh Wardhan SainiNo ratings yet

- John Adams - Defence of The Constitutions of Government of The United States of America, VOL 2Document466 pagesJohn Adams - Defence of The Constitutions of Government of The United States of America, VOL 2WaterwindNo ratings yet

- Why Is The Askokin Intimately Related To WarsDocument2 pagesWhy Is The Askokin Intimately Related To WarsRemus NicoaraNo ratings yet

- SFCC 140th/ SFCCAAON Annual Dinner 2009 Program BookDocument24 pagesSFCC 140th/ SFCCAAON Annual Dinner 2009 Program BooksfccaaonNo ratings yet

- Sample Questions Asked Thesis DefenseDocument8 pagesSample Questions Asked Thesis Defenseafkomeetd100% (1)

- CounselingDocument23 pagesCounselingrashmi patooNo ratings yet

- Patent Law OutlineDocument10 pagesPatent Law Outlinenumba1koreanNo ratings yet

- Measuring Place Attachment FactorsDocument4 pagesMeasuring Place Attachment FactorsAndrea Díaz FerreyraNo ratings yet

- Tom Moylan, Raffaella Baccolini (Editor) - Demand The Impossible - Science Fiction and The Utopian Imagination (2014, Peter Lang)Document363 pagesTom Moylan, Raffaella Baccolini (Editor) - Demand The Impossible - Science Fiction and The Utopian Imagination (2014, Peter Lang)luciananmartinez0% (1)

- Dadli Endru - Izazov Fenomenologije (K. Napomena)Document2 pagesDadli Endru - Izazov Fenomenologije (K. Napomena)milanvicicNo ratings yet

- Research Plan Methodology GuideDocument19 pagesResearch Plan Methodology GuideMarcksjekski Lovski0% (1)

- Educational technology conceptsDocument23 pagesEducational technology conceptsJuliet Pillo RespetoNo ratings yet

- ICT Form 5 Chapter 1Document34 pagesICT Form 5 Chapter 1Benammi Al-KhawarizmiNo ratings yet

- Essential Practices: For Overcoming InsecurityDocument19 pagesEssential Practices: For Overcoming InsecurityFariza IchaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Creativity in EntrepreneurshipDocument14 pagesThe Role of Creativity in Entrepreneurshipyoshita91No ratings yet

- MexicanamericanwarcommondbqDocument14 pagesMexicanamericanwarcommondbqapi-292351355No ratings yet

- Laser Beam Expander Guide: Theory, Types & ApplicationsDocument14 pagesLaser Beam Expander Guide: Theory, Types & ApplicationsJayakumar D SwamyNo ratings yet

- School Name My Family - Listening Comprehension NameDocument2 pagesSchool Name My Family - Listening Comprehension NameDelia ChiraNo ratings yet

- Fuzzy LogicDocument21 pagesFuzzy LogicDevang_Ghiya0% (1)

- The 5 Core Functions of ManagementDocument138 pagesThe 5 Core Functions of ManagementLords PorseenaNo ratings yet

- ISO 26000 PresentationDocument21 pagesISO 26000 PresentationcompartimentssmNo ratings yet

- DeliveryOpenSourceModelBasedBayesian Gunning 030203Document46 pagesDeliveryOpenSourceModelBasedBayesian Gunning 030203Thomas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Conservation of Linear Momentum, Momentum & Impulse, Mechanics Revision Notes From A-Level Mathat TutorDocument4 pagesConservation of Linear Momentum, Momentum & Impulse, Mechanics Revision Notes From A-Level Mathat TutorA-level Maths TutorNo ratings yet

- Satanic SymbolsDocument123 pagesSatanic SymbolsPoorna Kalandhar67% (9)

- Dispersion staining using cardioid darkfield condenserDocument7 pagesDispersion staining using cardioid darkfield condensermarkoosNo ratings yet