Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Quarter-Life Period

Uploaded by

kevin bayu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views21 pagesquarterlife crisis

Original Title

The_Quarter-Life_Period-converted

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentquarterlife crisis

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

35 views21 pagesThe Quarter-Life Period

Uploaded by

kevin bayuquarterlife crisis

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 21

Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 DOI 10.

1007/s 1059 1-008-9066-2

The Quarter-life Time Period: An Age of Indulgence, Crisis or Both?

Joan D. Atwood - Corinne Scholtz

Published online: 10 June 2008 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008

Abstract A new developmental stage called the quarter-life is proposed, extending from

approximately 18-29 years of age and sometimes later. The emergence of this period is

believed to be the result of several social, historic and economic factors that occurred post

WWII. This article explores these changes in terms of the experiences of affluent young

people in today’s Western society. A typology of adaptational responses are presented and

explored as the quarter-lifers attempt to navigate their way to adulthood within the context

of this ‘new’ affluent society. Implications for family therapists are considered.

Keywords Stage of development - Late adolescent issues - Quarterlife time period - Affluent

society - Typology of quarterlifers - Therapy implications

The concept of adolescence became current in the very early 20th century with the pub-

lication of a book by G. Stanley Hall (1904). This was the first discussion in which

adolescence was described as applicable to a specific time period and as having a distinct

set of behaviors. As societies became more and more industrialized, extensive training was

required, necessitating young people to attend school for a greater number of years. This

extended the period between childhood and adulthood. Adolescence as a distinct phase of

social development is thus a relatively modern phenomenon—one that is characteristic of

advanced industrialized societies with extended educational systems. This stage arose

when it was recognized that young people held norms and beliefs that were significantly

different from their parents and that there appeared to be a period of confusion or

ambivalence that represented a transitional period from childhood to adulthood.

J. D. Atwood (&)

Marriage and Family Therapists of New York, 542 Lakeview Avenue, Rockville Centre, NY

11570, USA

e-mail: jatwood @optonline.net

C. Scholtz Nova University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

Q Springer 234 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

Prior to the creation of this distinction, children entered the work force at young ages and

there was no stage that represented a waiting period. Eventually, it was this “waiting

period” that came to be seen as a separate stage of life—adolescence. It was believed that

this time period represented a time of anomie because neither the norms of childhood nor

the norms of adulthood were applicable. According to Seeman (1976),” anomie denotes a

situation in which the social norms regulating individual conduct have broken down or are

no longer effective as rules for behavior” (p. 406). With no norms for behavior available to

guide individuals, persons became unsure of and confused by which norms of behavior

were expected of them and thus adolescence became associated with storm and stress.

Currently, as technology continues to increase and training for specialized jobs requires

more and more schooling, the stage of adolescence has extended once again. Some the-

orists are redefining the end markers and calling for a new stage of life, one that is in

between adolescence and adulthood (Robbins 2004; Robbins and Wilner 2001). Although

there is no magical line that demarcates adolescence from adulthood, we define the

quarter- life period as the time of life in between adolescence and adulthood. This time

period correlates roughly with the ages 18~30. Robbins and Wilner (2001) refer to a crisis

of the quarter-life as occurring somewhere between leaving adolescence and two decades

before the “mid-life crisis’”—basically around the early twenties. Grossman (2005) extends

the definition of what he calls the “twixsters” as persons who are clearly not adolescents

but who are not meeting the standard criteria of adulthood, sometimes even by age 29.

Gordon and Shaeffer (2004) call this period of life “adultscence.” Amett (2004) presents a

com- pelling portrait of the lives of people he calls “emerging adults.” He argues that in

recent decades, a new stage of life has developed, usually lasting from about age 18 through

the mid-twenties, and distinct from both the adolescence that precedes it and the young

adulthood that comes in its wake. This new stage is one of identity exploration, instability,

possibility, self-focus, parental conflict, and of a substantial sense of limbo. What is valuable

to note is that the extended time period between adolescence and adulthood is increasingly

recognized by theorists. This is particularly relevant to marriage and family therapists

(MFTs) who frequently interact with these young people in therapy.

It appears that young people in their twenties and early thirties are making a statement

about adult life in the 21st century, pushing theoreticians to reconsider the adult markers

of development. It is crucially important for MFTs to be aware of the sociological influences

of these changes as the roots of the new life-stage do not appear to be limited to changes in

the family system; but rather seem to be familial adaptations to socially constructed

technological changes and social expectations.

In this article, we first explore the larger context—the social factors that appear to

influence the quarter-life time period, and then discuss the clinical adaptations to these

changes, exploring the socially constructed meanings and describing the resulting issues as

young affluent people may typically experience them. In addition, there is a consideration

of the type of confusion or anomie created by an affluent society. Therapeutic consider-

ations are then presented.

Demographics of the Quarter-life

Young adults make up 27.7% of the population. Sixty-seven million Americans were

between the ages of 18 and 34 in 2000. About three-fourths of young adults aged 18-34 are

in the labor force. About 80% of those aged 18-34 have a high school degree. Sixty-one

percent have some college and one in five (20%) aged 18-34 have a 4-year college degree

1) Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 235

or higher (U.S. Census Bureau 2003). As will be described, the many social changes our

society has undergone have had profound effects on a large percentage of young people.

Globalization

Globalization is defined as a historical process, the result of human innovation and tech-

nological progress. It also refers to the increasing integration of economies around the

world, particularly through trade and financial flows (Bordo et al. 2005). The term

sometimes also refers to the movement of people (labor) and knowledge (technology)

across international borders. While globalization has many advantages, it also has disad-

vantages in that it may intensify economic deprivation, increase class divisions, and thus

increase differential access to resources, wealth and opportunity, creating inequality of

access to and achievement of resources, and perhaps also a redefinition of the meaning of

socially defined goals (World Youth Report 2003). Globalization, while defined as a

historical and economic process, has profound social implications.

Some young adults’ experience of globalization appears to be riddled with uncertainty. The

degree of that uncertainty varies according to social environments and much depends on

the extent to which individuals have the cultural and financial resources to offset the risks

associated with the apparent increase in patterns of inequality (Mills and Blossfeld 2003).

This is not to say that young people are passive recipients of social trends. Rather, the

economic benefits of globalization do not necessarily trickle down to all members of society

equally. Some are more vulnerable than others. Mass media and the technological

revolution have played a key role for young adults in the postmodern era. It is believed that

there is a growing gulf between the classes—between those who are information-rich and

those who are information-poor or as Simon and Gagnon (1976) point out, there are

profound differences between certain segments of society in terms of resources. Young

people in both these situations will experience anomie—the anomie of scarcity and the

anomie of affluence. However, the expression of the anomie may differ.

The Anomie of Affluence

We emphasize the anomie of affluence because we believe it to be more related to the

development of the quarter-life time period and the potential development of the quarter-

life crisis. Durkheim (1898), a classic sociologist, first described the concept of anomie in

the early 19th century as that condition in which social metaphors lose their ability to

organize personal metaphors. He was addressing the connection of everyday life to the

socially defined meanings of society. In other words, anomie occurs when people’s

behavior is not regulated or tied to the social order—the goals and means of achieving

those goals do not hold much value to individuals. Anomie has commonly been referred to

as a state of normlessness, a lack of a blueprint for behavior. Merton (1938), another classic

sociologist, explores the means of achieving the socially defined goals of society and points

out the unequal access to those goals. Simon and Gagnon (1976) discuss the notion that in a

society based on deprivation and scarcity, achieving goals is primarily a struggle, and the

final achievement of the goals is rewarding.

However, in a society, especially one post WWI, the struggle of hard work, thrift, and

deprivation to obtain social goals may seem remote to young people growing up in that

society. Post WWII society holds easy access to goals, but what could be problematic in

g Springer 236 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

this society is the commitment to the goals in the first place and the resulting gratification

or lack thereof when those goals are finally achieved. This post WWII society provides its

young people with many goals and many different means to achieve them. Simon and

Gagnon (1976) believe “that a society that keeps these promises with such ease and

abundance can trivialize them to the point where achievement no longer affords what has

been called ‘consummatory gratification’” (p. 361). Individuals no longer are tied to the

existing social and moral order. Instead, those ties are weakened, lending to the experience

of anomie and in some cases, deviant behavior. In essence, the rewarding feeling of

achieving the goal decreases along with the value of the goal. If everyone has a Rolex and

they are easy to obtain, the status of owning one declines as does the pleasure associated

with owning one. So, as defined by Simon and Gagnon (1976), “...the anomie of affluence is

easy access—indeed, overly easy access—to institutionalized means of achieving the major

goals of society” (p. 369). Further, once the goal is achieved, it is questionable that this

achievement will generate adequately rewarding levels of gratification. Thus, it may be

difficult for young people to identify with the goals their parents have defined.

These notions are directly related to the quarter-life. In an affluent society, such as that of

the post WW II United States, there is an abundance of social goals and many oppor-

tunities for access to these goals. In general, young people, as Simon and Gagnon (1976)

point out, seem to have a much cooler, more detached attitude toward achieving posses-

sions for themselves. Achieving status, things, and/or prestige do not necessarily mean

much to these young people as they have had material wealth handed to them by their

parents. Very recently, in fact, some young people report that they feel inadequate next to

their parent’s accomplishments (Kamenetz 2005). Their parents were the ones who went

from rags to riches post WWII. These parents provided their children with a very com-

fortable life-style—a life-style very few young people today will be able to achieve on their

own. Some try anyway; some aspire to very different goals from their parents; others just

give up.

Information and Technology

Living in a world in which rapid change constantly revolutionizes the process of gathering

and receiving information has led in many ways to a generation that expects instant

gratification and has a sense of entitlement. Young adults have grown up with very dif-

ferent images than their parents, having been reared in a culture popularized and

reinforced by mass media that has a powerful voice in today’s society. The wide range of

explicit images and/or messages that have been communicated and internalized have

created a different childhood experience for today’s adult children (Arnett 2004). Some

state that media influences have become so powerful that the family and community

strength of socializing the young has decreased as mass media, technology and the

information explosion have increased. Those who believe this premise also believe that

mass media is then a primary source of socialization and thus a major factor involved in

identity for- mation in vulnerable young people.

The Privileges of the Child

This is a generation that is growing up with working mothers and fathers. As a result of

expanding parental roles and conflicting pulls between work and family, family life has

® Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 237

become increasingly participatory. The once hierarchical structure of the traditional family

is now a minority, with the ‘new’ family becoming more democratic and collaborative.

Children have more of a “say” in these families; they are encouraged to freely express

themselves (Day et al. 2002). Having achieved an accumulation of material wealth, there

seems to be an increase of parental indulgence in material items. As a result, children are

more prone to define themselves in terms of their possessions. As stated by Taffel (2001),

we are victims of a consumer culture and drive ourselves to attain possessions — the best

cars, houses, tv’s, clothes, and other worldly goods, not to mention the hottest stocks — our

children are stricken by “the gimmees,” an unrelenting need for the artifacts of the pop

culture and the erroneous assumption that things buy happiness.

(p. 3)

This type of indulgence and affluence can create a false sense of esteem in young people.

Material goods seem to define who they are; what they possess and the brands that they

wear—their outer selves—momentarily give them a sense of confidence and esteem. While

their outer selves seem polished and manicured, there is no recognition that the confidence

and esteem that they are seeking comes intrinsically from within. This seeming lack of

connection to a self that is defined beyond one’s external world is often a factor in one’s

struggle for identity - particularly when contending with a quarter-life crisis.

The Value of Individualism in Western Culture

In addition to technological access, affluence, and indulgence in the environment of young

people, the emphasis on individualism and independence in US culture is also very rele-

vant. “The criteria most important to young Americans as markers of adulthood are those

that represent becoming independent from others (especially parents) and learning to

stand alone as a self-sufficient individual” (Arnett 1998, p. 296). Individualism and

indepen- dence are very prominent values and features in Western society’s conception of

adulthood. While the post-modern young adult is in transition or in a waiting period

between adolescence and adulthood, taking on a role can mean compromising one’s

individualism, and in some ways one’s independence, in order to conform to the

requirements of the role. It is entirely possible this is related to the fact that marriage and

other role transitions are rejected as important criteria for entering adulthood by the

current generation of young people (Berger and Luckman 1966).

Too Many Choices

There are a bewildering number of choices facing emerging young adults today and no

definitive way of deciding which ones are the ‘right’ choices. In this period of transition,

there is little that is normative. While there is a script for behavior during adolescence and

a script during adulthood, there is no script for this new period—just bits and pieces from

many scripts from which young people feel they have to choose. This can create a state of

anomie, not having a script or blueprint for behavior, causing this time of life to be called

emerging adulthood (Arnett 2001).

As stated earlier, emerging adulthood is defined as a period of life bridging adolescence and

young adulthood, during which time people are no longer adolescents but have not yet

attained full adult status. They are in the process of developing the skills, capabilities, and

Q Springer 238 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

qualities of character deemed by their culture as necessary for completing the transition to

adulthood, It is a period of intense focus on preparation for adult status. It is a time of life

when many different directions are possible, when little of the future is certain, and when

the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most than it will be

at any other time of life.

Unstable Residential Status

There is a time for departure, even when there’s no certain place to go. Tennessee Williams

Currently, eighteen million 20-34 year olds live with their parents. In the 1930's, only 25%

of those who left home returned. In the mid-1980’s, this figure rose to 40% and today, it is

as high as 60%. Most adults leave home by 18 or 19: 1/3 goes off to college after high

school and spends approximately 4 years in semi-independent living conditions. Forty

percent move out of their parent’s home not for college but for independent living and full

time work: 2/3 cohabit with a romantic partner. Some remain at home while attending

school, and 10% of the men and 30% of the women remain at home until marriage. But, for

about 40% of the current generation, residential changes include moving in and out of their

parents’ home (Infoplease 2005).

Such behavior is different from that of their parents and can be a source of additional

conflict between the generations. Members of the parental generation grew up knowing

that once they reached their twenties, they were on their own. Whether they chose to

become part of the establishment or to drop out, or if they decided to get married and start

their own families, they did not continue to be dependent on their parents. Many of them

did not stay single for an extended period of time after high school or college, and their

twenties began with the assumption that they would live happily ever after. The young

people of today may question the wisdom of their parents in this regard; the world is a

different place and the cultural and societal rules their parents followed may no longer

make sense for the emerging adults of today.

Finances and Debt—-Generation Broke

One report (Draut and Silva 2004) indicates that the economic security of younger

Americans is eroding at an alarming pace as a result of slow wage growth, underem-

ployment, rising costs and mounting student loan and credit card debt. According to

another report, the youngest adult households (aged 18—24) with debt spend nearly 30

cents of every dollar earned servicing debt, twice the amount spent on average in 1992

(Mintel Report 2004). Credit card debt among the youngest adults (aged 18-24)

skyrocketed 104% during this same period to $2,985. Student loan balances have doubled

in the course of a decade. The average 2002 graduate carried $18,900 in debt versus $9,000

for 1992 graduates. By 2005, they carried over $20,000 in student loans, a figure that has

doubled in a decade. Unemployment rates have risen faster for younger workers than for

those in other categories: | in 10 was unemployed in 2003 (Mintel Report 2004), At this

point in time, it seems that young people are marginalized in terms of their economic

power. Marginali- zation plants the seeds for emotional issues to surface while also

increasing the possibility for alternative behavior patterns to emerge.

® Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 239

Another example relative to young adults and the reality of financial independence is the

fact that today’s young adults tend to pursue opportunities that provide short-term

rewards. They often find themselves clinging to their jobs amid layoffs, hiring freezes, etc.

Although the number of college graduates has remained consistent over the past few years,

the number of unemployed college graduates has increased 20%. In fact, college degrees

offer less job security than ever before. As of March, 2004, there were 1.17 million

unemployed college graduates. Young adults are entering this period with debt, from both

school and credit cards, in greater amounts and more often than ever before (Gordon and

Shaffer 2004). In addition, this group is less likely to have jobs with adequate health

insurance, and if they have pensions, they are less likely to be guaranteed. This is very

different from their parents. Many parents believed in no debt, pay bills on time, and if you

don’t have the money, don’t buy it.

Generations in Conflict

Some of the issues faced by these young adults are exacerbated by a lack of understanding

of the differences and similarities between generations. Change in and of itself creates a

natural tension between generations. As children, emerging young adults were told to start

thinking about their resumes before they were teenagers. They took courses to prepare

them for Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Tests (PSATs) and more courses to prepare them

for Scholastic Aptitude Tests (SATs). Our children are encouraged to choose a sport and

develop it so they can apply for scholarships and increase their chances for getting into a

good college. In fact, a new occupation has recently appeared—a career that assists young

people and their parents with filling out college applications. The pressures to succeed and

to obtain a status occupation after graduation are enormous. In addition, there is some

indication that young people’s achievements affect their parents’ own sense of self-worth

(Adams 2004), possibly creating a recalcitrant loop of parents trying to ensure their

children’s happiness and young people achieving in order to please their parents, perhaps

adding even more anxiety to the family system. These pressures begin at increasingly early

ages,

Relationships and Quarter-life

Young men and women may expect their future marriages to last a lifetime and to fulfill

their deepest emotional and spiritual needs. Yet they are involved in a mating culture that

may make it more difficult to achieve this lofty goal. Today’s singles mating culture is not

necessarily oriented toward marriage, as the mating culture was in the past. In fact, dating

patterns of young adults today bear almost no resemblance to dating patterns of the past

(National Marriage Project 2000). Many of today’s young adults must blaze their own trails,

create and follow their own paths. Evolving technology, increased access to edu- cation,

relaxed social norms, and the information age give young adults a very different

perspective from that of older adults.

Extending the beginning of adulthood into the twenties has influenced the perception of

young adults when establishing committed relationships. According to the National

Marriage Project (2000), young adults, are, either by choice and/or due to circumstances,

willing to spend the time looking for their soul mates rather than marrying young, People

are living much longer now than they used to, and young adults may speculate about their

g) Springer 240 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

parents’ decision to settle down at younger ages, believing that it may have been a con-

tributing factor to over 50% of their marriages ending in divorce. As a result of the high

divorce rate of their parents’ generation, young adults today are deciding to marry later

and are living together before marriage more than their parents ever did. “Both women and

men favor living together as a way of gathering vital information about a partner’s char-

acter, fidelity and compatibility” (National Marriage Project 2000). Many young adults are

also choosing to live alone or with people they are not related to prior to marriage. This

was very uncommon in the past (Gordon and Schaffer 2004). Increasing numbers of young

people say that they look to education as the principal means for increasing their chances

of marital success. They would like to learn how to communicate more effectively and to

resolve conflict in relationships.

Putting financial independence ahead of marriage is not new for young men. Tra- ditionally,

men have had to prove to themselves and to others that they were able to make a living, or

at least had the education or training to make a good living, before they could take on the

responsibilities of supporting a family. For women, however, the goal of achieving

individual financial and residential independence before marriage is relatively new. We

found that women are just as committed as men to making it on their own and getting a

place of their own before marriage. They cite the high rate of divorce, their past experience

of failed relationships, and their desire to avoid the same mistakes their mothers made, as

reasons why they are intent on independence (National Marriage Project 2000).

The Old Developmental Tasks of Adolescence

The benchmarks used by traditional developmental theorists may no longer be relevant ina

post-modern society nor may they occur at the ages previously described. In addition,

please note that the measures of familial and individual health that are typically used by

mental health professionals, including MFTs, may or may not be as relevant as they once

were or, at least may not be as typical of affluent youth. Other benchmarks may be

becoming more important as family health markers. And thus, more research is needed.

Erikson (1950, 1968) believes the primary focus for the adolescent and young adult centers

around identity and role confusion:

The young person must develop some specific ideology, some set of personal values and

goals...the teenager must not only consider what or who she is, but who or what she will

be...if these identities are not worked out, then the young person suffers from a sense of

confusion, a sense of not knowing what or who she is. (p. 57)

Interestingly, more recent research has found that most identity exploration takes place in

the years beyond adolescence, and there is evidence that identity achievement is rarely

reached by the end of high school (Montemayor et al. 1985; Waterman 1982), thus lending

support to an extended period of time between adolescence and adulthood.

In addition, according to Erikson (1950, 1968), a person must take a risk in creating an

intimate relationship with another and the immersion of the self into a sense of “we.”

Levinson (1986) believes that early adult transition (17-22) consists of moving out of the

pre-adult world, exploring possibilities and making tentative commitments. Between 22

and 28, the developmental task involves creating a major life structure, for example,

a Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 241

marriage, home, mentor, and a dream. As was discussed earlier, in a society where over

50% of marriages end in divorce, young people may be reluctant to enter into more

permanent, intimate relationships. In addition, they may not feel financially equipped to

take on the responsibility of a family until they are older.

The developmental tasks that are listed by the major developmental theorists are not

necessarily in agreement with the experience of today’s young individuals. According to the

former, the criteria most important in defining the transition to adulthood are the

individualistic character qualities of accepting responsibility for one’s self and making

independent decisions along with becoming financially independent. Thus, independence

(especially from one’s parents) and learning to be a self-sufficient individual are the most

important criteria for young people in terms of defining their own transition into

adulthood. Marriage, interestingly enough, has been ranked very low (Arnett 1997).

Thus, the long believed markers of adulthood are in flux; they need to be redefined for

young people in this postmodern society. The traditional definers of family health also need

to be examined in terms of their relevance in contemporary society.

The Quarter-life Crisis

It is important to note that not all young people absorb the messages of the dominant

culture in a uniform way. Some young people will become confused during this time,

resolve their confusion, and then go forward with their lives. Others may experience the

time period in an intensified way and some may seek out therapy for assistance in

resolving some of the issues. And still others may become part of the medicalization of

today’s youth and begin taking anti-depressants and/or anti-anxiety medications to soothe

their worries. Increasingly, this time period is becoming problematic for young people. The

kind of emotional crisis among twenty somethings—the sense of desolation, isolation,

inadequacy, and self-doubt, coupled with a fear of failure that many report in therapy is

what is referred to as the Quarter-Life Crisis (QLC) (Robbins and Wilner 2001).

Personal symptoms can range from mild anxiety to full blown panic attacks and/or

depression. Young adults experiencing the QLC tend to go through periods of insecurity

and then they feel confident. They feel alone, confused, and anxious one minute and social,

centered, and calm the next. These feelings can change from one minute to the next, so that

unpredictability may be the only predictable factor in their lives. Short attention spans,

poor focus, and an emphasis upon self-help and a search for self-fulfillment are charac-

teristic of this crisis. Uncertainty about the future is a major theme that is fundamental to

the QLC (Robbins and Wilner 2001),

Adding to this, because of technology and mass media, young persons may spend quite a bit

of time alone. Research (Jonsson 1994; Larson 1990) has found that young Americans ages

19-29 spend more of their leisure time alone than any other persons except for the elderly

and spend more of the time in productive activity (work and school) alone than any other

age group under 40. This means also that young adults explore their identity tran- sitions

alone without the companionship or support of peers or family.

Typology of Adaptive Responses to the Quarter-life Period of Life

The QLC (Robbins and Wilner 2001) is characterized by the confusion and anomie that

young people may experience when the norms of adolescence are no longer relevant and

the norms

g) Springer 242 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

of adulthood do not yet fit. What are the implications and adaptations to this specific type

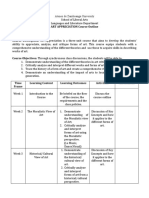

of anomie experienced by young people? Simon and Gagnon (1976) posit a typology of nine

adaptations that are directly applicable to the quarter-life time of life. They point out that

most people have access to the means of achieving the rewards offered by society but that

the feelings of gratification associated with the achievement of social goals varies. Table |,

based on Simon and Gagnon’s (1976) original typology, alters the categories somewhat,

taking into account the potential adaptive experiences of those within each category. What

we are proposing is that the sense of reward associated with the achievement of the

socially valued goal will then influence whether the person will experience a QLC. This

revised typology (See Table 1) is simply a visual representation of the possible adaptations

to the anomie of affluence. The yes and no answers refer to whether the person has

committed to the goals, has the means of achieving the goals, feels a sense of

accomplishment or reward when he or she achieves the goals, and whether he or she will

be likely to enter therapy. “Alternative” refers to the young person finding other ways of

defining, accomplishing and/or experiencing the goals. Please note that these are

typologies, merely descriptions of the types of issues that mental health practitioners might

see in therapy. The purpose of presenting them is to give MFTs examples of the kinds of

stories that young people may bring to therapy during this life period. What is needed now

is research in this area.

The first type of response applied to young adults describes those individuals who are the

most conforming—those who have internalized the means and goals of society. These

young people define the goals as desirable, have access to the means to achieve the goals

and fee] rewarded when they accomplish the goals. These are individuals who are most

committed to society. They experience the rewards of their achievements and there is no

threat that they would violate any laws or experience any social or psychological distress

around time of life pressures.

Emily is a 27-year-old wife and mother of a !-year-old. She has just completed her Ph.D. in

environmental science and has since been hired at a prestigious university as a professor.

She is committed to her career and family goals, and has accomplished both within a

reasonable time frame. She feels gratified and believes that she will reap the rewards of her

accomplishments both personally and professionally.

Table 1 Typology of adaptive responses to the quarter-life period of life

Commitment Means of Sense of Participation to goals achieving goals gratification in

therapy 1. Conformist Yes Yes Yes No 2. OK No Yes No Yes 3. Workaholic No Yes No Yes 4,

Thrill Yes Yes No Yes seekers 5. Detached No No No Yes person 6, Drug use No Alternative

Alternative Yes 7. Scam artist Yes Alternative Yes No 8. Joan of arc Alternative Yes

Alternative No 9, Rebels Alternative Yes Yes No 10. Rejectors Alternative Alternative Yes

No

Based on Simon and Gagnon (1976, p. 370)

® Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 243

It is likely that Emily would not experience the confusion and/or anxiety indicative of the

QLC and it is unlikely that she would go for therapy at this point in time.

Members of the second group see the goals as “OK” and will achieve some gratifi- cation,

but the ambition to succeed and sense of reward when they do achieve is lower than for the

first group. Persons of the second type define sources of achievement as adequate, but they

are not necessarily devoted to the goals. They do what they have to do. They get by. They

achieve but without passion or joy. As young people, they may switch from job to job but

without a plan, making money when they have to pay bills.

Sally is 28 years old and returning to school in order to earn a degree in physical therapy.

She is very committed to her goal of achieving her degree. Anything that can be considered

a distraction is put on hold, including personal relationships and working full-time. She

declares that she does not do what she wants to do; rather, she does what she has to do—

what she believes is required of her to obtain her goal. She is quickly frustrated and

complains three months into the program that perhaps she has chosen the wrong school.

She cannot wait until graduation when she can then begin paying back her $100,000

student loan debt.

In Sally’s case, the schooling is simply a means to an end and she does not receive a great

deal of personal satisfaction from her courses. Members of this group may present in

therapy because they see their friends enjoying the things that have been sacrificed in

order to reach their goal. At some point, they may wonder if the choice they made is worth

it. They may present in therapy with feelings of depression and/or anger if their parents

are pressuring them to settle on a career.

The third type is the “workaholic.” Individuals in this group are committed to achievement

but they do not receive gratification from the achievement of their goals. These persons do

lots of work but do not experience any real satisfaction or feelings of accomplishment when

the goal is achieved. As soon as one project is completed, another must start. Simon and

Gagnon (1976) refer to this as a “thirst for achievements” (p. 371).

Cindy is 25 years old and anxious and worried about her future. She learns a job quickly

but needs a constant challenge to keep her from being bored. As soon as she has mastered

something, a new goal must take its place. Instead of a sense of satisfaction when she

finishes a task, she experiences feelings of emptiness and becomes restless until she finds a

new project.

Young persons such as Cindy may present in therapy because they may just as easily

become bored in relationships, over-function, and become restless at work. They may mask

their anxiety at not being able to find satisfaction with anything in their lives. This is the

type of person who climbs the ladder of success only to realize at forty that it has been

leaning against the wrong wall. The pursuit of external accomplishment diverts attention

away from having to figure out their authentic feelings. These individuals may present in

therapy feeling unhappy, empty and/or depressed and may self-medicate the anxiety

and/or depression with drugs.

The next group of individuals, the fourth group, could be called the “thrill seekers.”

Individuals in this group will seek out experiences simply because they are there. They

have achieved gratification from their accomplishments, but it is short lived and they feel

that they must pursue more and more activities and experiences. Their quest for new

experiences can begin to consume them. The focus is on self-gratification but the self is

never fully gratified.

Q Springer 244 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

Ron, age 28, was determined to make a lot of money fast. He wheeled and dealed as a

trader on the stock market and his bonuses got bigger and bigger. His goal was money. He

decided to buy an airplane. He took flying lessons and eventually obtained his pilot’s

license. Then he bought a boat and sailed up the East Coast of the U.S. He wanted a fast car

so he bought a Porsche and would “drag” race sometimes at stop lights. He liked the rush.

His latest endeavor was to go out West to join a thrill seeking expedition.

Ron and others in this group may feel like bottomless pits and may come to therapy

reporting that they feel empty. They also may experience anxiety as they look for the next

thrill seeking activity.

Persons illustrative of the fifth type, the detached person, reject both the means of

achievement and the rewards associated with the achievement of the goal. In this case,

there is no commitment to anything except not making a commitment. They simply are not

interested. They may come to therapy depressed. This group may tend to feel a sense of

anhedonia, no joy in life, no excitement about people or things. They have no real desire to

be in a relationship; it simply takes too much energy. These persons may be suicidal at

some point in life.

Paul is 29 years old and is not interested in a career or a relationship. He simply does not

want to deal with other people’s drama. He procrastinates, never really accom- plishing the

major tasks of adulthood, which include finding fulfilling work and love. He prefers to live

alone and work in isolation, as the owner of a small business or as a computer

programmer, in solitary activity, often making just enough money to get by. He questions

the idea that there is someone for everyone, and shuns the responsibility of getting

married. Besides, he feels, everyone ends up divorced anyway. By the time he reaches

thirty, he may feel that he has seen all that life will offer him.

A younger version is typified by Chris:

Chris is 25 years old. He tried college but didn’t like it. He had a job as a painter for a while

and occasionally works for a friend when he wants money. For a while, he considered

becoming an actor, so bought some books on acting. Then he thought he should join the

Coast Guard but changed his mind at the last minute.

This type of individual may go for therapy if his family begins to pressure him and/or if he

begins to increase his isolation, He may become suicidal at some point, believing that there

is nothing more to life. He feels that he is unable to make his own meaning and purpose.

The sixth category refers to those who reject the achievement commitment but accept

innovative or possibly deviant styles of gratification. The drug cultures would be an

example of this type. There is a rejection of the achievement norms but a commitment to

seeking new and different modes of gratification. This group would want to alter con-

sciousness/reality to see how good it feels.

Joe is 30 years old and is constantly haunted by a sense of anomie. Although he has a

college degree, he is not interested in holding down a full-time steady job. He is lonely and

thinks he wants a serious relationship but he is unsure if he could handle the responsibility

involved. He believes that he is not good relationship material. Working does not provide

any sense of achievement and, besides, he thinks he is smarter than most of the people he

works with, including his bosses. Highly intel- lectual, he is committed to experiencing

highs and looks to escape his lonely life that

a Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 245

does not mirror that of his peers. Losing himself in drugs and alcohol is the only real

gratification he seems to find in his life. The only time he feels confident and good about

anything is when he is taking drugs. As the years go by, it may become harder and harder

for him to change.

Another Case:

Keith is 24 years old. After switching from college to college, he moved back home with his

parents so he could attend a local community college in the area to see if he could earn an

Associates Degree. He is waiting to hear from a European Soccer Team to see if he could

join them on a semi-professional basis. When he needs money, he works as a coach but, for

the most part, stays home and smokes pot with his friends.

People like Joe and Keith may present in therapy because they begin to wonder if they can

ever fit into society. They may feel that they are just are not motivated to push on with

their lives, and this may make them feel uncomfortable at some point.

Members of category seven want to change the means of achieving social goals, but accept

those aspects of life that are consonant with a successful life. They aspire to the good life

but want to change the methods for achieving it. They could create new and possibly

deviant modes of obtaining the desirable socially defined goals. They may be represented

by the con-artist who would scam people out of money and use it to buy a Status car.

Jeremy, age 26, lives with his girlfriend, Lauren. He tells Lauren he loves her and wants to

marry her but he doesn’t feel ready just yet. Lauren works and supports the two of them.

Jeremy stays at home and sleeps all day. He tells Lauren he cannot work because he has

anxiety; however, he is very social and goes out with his friends most weekends. He wants

Lauren to take out a loan and buy him a new car for his birthday because he is feeling

depressed.

It is unlikely that this type of person would present in therapy. Similar to Jeremy, he might

be living with someone who is supporting him or achieving “things” in ways that are

consonant with a scamming mindset.

Individuals in the eighth category, the Joans of Arc, are very committed to changing the

social goals and see themselves as instruments of change. They do not receive pleasure

from achievement. Rather, they see themselves as self-sacrificial in a way. Their purpose in

life is to change society; their self is unimportant. These are persons who devote their lives

to helping others; if they are helping the poor, they may give them their money, living in

poverty themselves.

Alice is 24 years old and working at a non-profit agency helping the homeless population,

Although she does not see herself really settling down and pursuing any type of career, she

is satisfied because she feels that her work is making a difference. Every day when she

comes to work she embraces those who are less fortunate than she is and she is

appreciative daily of the blessings in her life. She finds her work internally satisfying. She

may not achieve the status or prestige of her peers, but she feels the scope of her work

reaches beyond the superficial standards of society.

It is unlikely that these individuals would present themselves in therapy as any

unhappiness is “good” because it is for a greater cause.

Individuals in category nine are the rebels of society. They seek to change the goals

associated with the social order and the lifestyle associated with those goals. These

Q Springer 246 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

individuals are the revolutionaries, the radicals—radical to anything. They want to over-

throw the existing social order and with it wipe away the lifestyle associated with that

order,

Frank, age 25, feels that society is going down the tubes. He wants to move to a commune-

like community in Nova Scotia. He feels the environment is increasingly being polluted and

destroyed and he believes all politicians are liars; he thinks society is overcome with

materialism; and believes that the God of society is money. He refuses to bring children into

this world and is not interested in any long-term relationships. He votes for the communist

party in every election because he feels that only by overthrowing the current political

order would any change occur.

These individuals generally will not come for therapy because they would see therapists as

untrustworthy (they might define them as social control agents—preserving the status

quo). As long as they were entrenched in a sub-culture of like-minded individuals, they

would feel emotionally content.

The tenth category represents the more extreme situations. In this case, the young persons’

behaviors are problematic not only for themselves but also for their families. They do not

want to leave the house and are content to stay at home or to stay in their room day in and

day out. This category can be called the rejectors because they reject not only the goals of

society and the means of achieving those goals, but they have no energy, interest or desire

to interact with people.

Tommy, age 17, cut out of school. A few weeks later, he stopped going to school altogether.

A few weeks after that, he didn’t venture outside the upstairs bedroom in his family’s home.

He slept during the day and stayed up all night, playing computer games, going on the

Internet, and watching CNN. His parents tried ordering him out, and when that didn’t work,

they tried coaxing or bribing him out only to hear in response, “Leave me alone!”

These persons generally would not come in for therapy unless pressured by significant

others—usually parents. They have rejected the goals of society, the means of achieving

those goals and they do not experience any feelings of reward or accomplishment. When

pressured by parents, they may become hostile and tend to withdraw completely.

A Word on Gender

It is crucial to acknowledge the influence of gender on one’s experience of the QLC and

possibly whether one will even have such a crisis. Many of the examples given above were

examples of young men. This is because the story of men and women in U.S. society is a

gendered one. The value in US society, although changing, is still that men generally are

expected to be the primary breadwinners of the family. They tend to provide most of the

family income. Their social role dictates that they “should” be successful in a career, make

money, support their families, etc. They operate primarily in the work situation; they are

interested in politics and sports. In general (and these are all generalizations) they are not

expected to be the nurturing members of society. Men also define themselves more in

terms of their occupations: I am a CEO; I am a carpenter.

Generally speaking, the woman stays at home and takes care of children. She is responsible

for nurturing, for taking care of the family and for the home. Even if she works outside the

home, as most women do in 2008, she operates under the belief that her family

® Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 247

comes first. In addition, women tend to define themselves more in terms of social rela-

tionships: I am a wife; 1 am a mother. Although these values are changing and may not

even be the reality for many at this point, they still are the dominant values of society,

It is the authors’ belief that young persons during this stage of life are aware of the goals

and ideals of the parental generations and many know and have the socially approved

means of achieving those goals. However, many young persons often feel that they have no

guidelines for navigating their twenties—for getting from one place to another (Robbins

and Wilner 2001). Not having guidelines may cause them to do some soul-searching as to

who they are, who they want to be, and what they want their lives to represent. Making

money, being successful, getting married and having children are the goals they were

taught that they should want and have, and many of them do. However, some may want to

achieve them in a different time-frame, and they may approach achieving them differently

from the parental generations.

Young adults may jump around from relationship to relationship, from job to job, not

because they are unable to make commitments, but rather, because their commitments

differ. They are committed to themselves —to finding their own meaning and purpose in

life, to pursuing their own happiness and freedom in whatever form that may be. Many are

committed to the pursuit of their own authenticity.

Implications for Family Therapists:

The Chinese symbol for the word ‘crisis’ is a composite of two pictographs: the symbols for

‘danger’ and ‘opportunity’. Although we would not wish for misfortune, the paradox of

resilience is that our worst times can also become our best.

(Wolin and Wolin 1993, as quoted in Walsh 1998, p. 7)

Throughout this article we have attempted to illustrate the effects of social and techno-

logical change on the lives of affluent, young people. If we consider that reality is, in part, a

social construction created by individuals through language (Anderson and Goolishian

1998), rather than that it is something “out there” to be discovered, one can conceptualize a

crisis to be reflective of a phenomenon constructed within one’s culture and community. If

crises are birthed through social processes, this eliminates viewing the individual as

owning a “problem” (McNamee 2002). Thus, how can one view the QLC in relational terms,

and what are the therapeutic implications of such a stance?

Many MFTs have been concerned with the relational construction of identity. (Anderson

and Goolishian 1988; Freedman and Combs 1996; Watzlawick 1978; White and Epston

1990). In thinking about the young people who fall into the QLC category, quarter- lifers

probably will present in therapy by themselves to examine their relationships with

themselves, with their peers, with work, with their parents and siblings, with significant

others, and/or with the culture in which they live. It is exactly for this reason that family

therapy, a relational orientation, is the ideal approach. According to McNamee (2002), “The

relational orientation this provides presumes that the client and the therapist are

cooperatively engaged in constructing a narrative about the client’s crisis” (p. 194).

If we consider for a moment that a crisis can be reframed into an opportunity to rescue

oneself from ideas imposed upon us by our culture, we create space for alternative

experiences and descriptions to take place. MFTs are ideally suited to assist with the

transition from adolescence to adulthood because their conceptualization of human

development, social change, and family dynamics is broad enough to incorporate the

Q Springer 248 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250

myriad of forces influencing the individual. Thus, the MFT understands the individual

within the context of the larger society, the community, the extended family, as well as the

family and peer group in which the individual participates. The MFT is aware of the impact

of stressors from work, family, society and culture. Even though there may be one person in

the therapy room, the MFT is able to maintain a view that extends beyond the individual.

Therapeutic Approaches for the QLC

Many different therapeutic approaches are available when working with an individual

struggling with the QLC. Because cultural stories act to organize people’s experience, and

aid in constructing a normative view, people come to identify themselves and compare

themselves against what is expected of them and considered appropriate. In the experience

of the QLC, these individuals are challenging the normative story of adult development and

achievement in today’s world. They are seeking the expression of a new story, one that

speaks to the dynamics of their lived experience and honors the struggles that are unique

to the world in which they navigate and create meaning. This serves as a reminder that,

“These stories people construct evolve in and are unique to the social and cultural, rela-

tional context in which they are constructed” (Zimmerman and Dickerson 1994, p. 236). As

such, change is constructed through the development of more flexible, viable, and useful

stories in collaboration with the therapist and through the use of language.

If we can assume that all behavior, emotion, and description make sense given the context

in which they occur, it becomes crucial for therapists to acknowledge how their client

understands and organizes experience. Inherent in this position is a stance of curi- osity,

and a willingness to remain in a not-knowing position. What this implies is that while the

therapist is the expert on psychological theory and process, it is the client who is the expert

on his or her life and experience. When confronted with individuals who feel they are lost

and failing in some way, it is crucial to have a framework in mind that counteracts any

motion to pathologize their struggles.

In an effort to move from a problem-saturated story of frustration, anomie, and

uncertainty, one may seek to provide a re-authoring context (Epston and White 1992),

while focusing upon possibilities and strengths already a part of the person’s experience.

(de Shazer 1998). O’ Hanlon (O’ Hanlon and Bertolino 1998) writes about brief therapy that

validates and acknowledges a client’s experience while collaborating in a new conversa-

tion that opens up space for possibilities to emerge: “In these conversations, we seek to

help people see the possibilities, be accountable for what they do, and take actions that will

help move them on into the kind of future they hope for” (p. 21), Interventions for the QLC

from a solution-focused orientation would include asking the miracle question, finding

times of exception when the presenting problem is not occurring, and using scaling

questions in an effort to move the client toward a preferred future and reality.

According to narrative therapists, such as Zimmerman and Dickerson (1994, p. 233),

In this work we pay attention to the larger cultural stories, including gender con-

structions, and to personal stories that persons have created to make meaning out of their

experience as they interact with one another in a reciprocal meaning-making process.

Interventions for the QLC from a narrative perspective would focus on “...externalizing the

problem narrative that is influencing the client(s), mapping the effects of the problem

Q Springer Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233-250 249

pattern and/or the totalizing view persons might have of others, and creating space for

client(s) to notice preferred actions and intentions” (p. 234).

Of utmost importance is that MFTs focus on change, not on diagnosing. They would see the

QLC as an attempt to negotiate the socially constructed world and the meanings contained

within it. The focus and co-construction by therapist and client would be on future, healthy

flexible realities. Thus, the goal of therapy “...is to participate in a con- versation that

continually loosens and opens up, rather than constricts and closes down” (Anderson and

Goolishian 1988, p. 381). It is a process of developing and creating new meanings,

understandings, and possibilities in an effort to free the individual from dis- course that is

constraining and restricting. It is inevitable that individuals will have internalized the

dominant assumptions of their culture, and have formed parts of their self- identity in

relation to these widely accepted and supported ideas.

It is important to remember that each of us is born into a given sociocultural envi- ronment

and as we learn the language of our group, we internalize the norms, values, and ideology

of this context. As Watts (1972) states “...our most private thoughts and emo- lions are not

actually our own...For we think in terms of languages and images that we did not invent but

which were given to us by society” (p. 64). “And knowledge as narratives embedded in

cultural stories is never final: It is always negotiable” (in Becvar and Becvar 1999, p. 11).

After all, just as the map is not the territory (Bateson 1972), so too, are there many ways of

getting to the same destination.

Acknowledgement A special note of thanks to Ian Nichols who assisted in the initial stages

of this work.

References

Adams, J. (2004). The kids aren’t all right. Retrieved February 2005 from

http://saqonline.smith.edu/ article.epl?issue_id=4&article_id=141,

Anderson, H., & Goolishian, H. (1988). Human systems as linguistic systems: Preliminary

and evolving ideas about the implications for clinical theory. Family Process, 27(4), 371-

393.

Arnett, J. (1997). Young peoples’ conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Youth and

Society, 29, 1-23.

Arnett, J. (1998). Learning to stand-alone: The contemporary American transition to

adulthood in cultural and historical context. Human Development, 41, 295-315.

Arnett, J. (2001). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through

the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480.

Arnett, J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the

twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. New York: Ballantine Books.

Becvar, D., & Becvar, R. (1999). Systems theory and family therapy: A primer. Lanham, MD:

University Press of America.

Berger, P., & Luckman, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the

sociology of knowledge. New York: Anchor.

Bordo, M., Taylor, A., & Williamson, J. (2005). Globalization in historical perspective.

National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report.

Day, D., Peterson-Badali, M. & Shea, B. (2002). Parenting style as a context for the

development of adolescent's thinking about rights. Retrieved February 12, 2008, from

http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERIC WebPortal/ custom/portlets/recordDetails/detailmini.jsp?

nfpb=true&& ERICExtSearch_Search Value_0=ED464746&

ERICExtSearch_SearchType_O=no&accno=ED464746.

de Shazer, S. (1998). Clues: Investigating solutions in brief therapy. New York: W.W.

Norton.

Draut, T., & Silva, J. (2004). Generation broke: The growth of debt among young americans.

Borrowing to make ends meet series. Retrieved May 2005 from

http://www/demosusa.org/pubs/Generation_Broke.pdf,

Durkheim, E. (1898; 1951), Suicide. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Epston, D., & White, M. (1990). Consulting your consultants: The documentation of

alternative knowledges. Dulwich Center Newsletter, p. 4.

A Springer 250 Contemp Fam Ther (2008) 30:233—250

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Freedman, J., & Combs, G. (1996). Narrative therapy: The social construction of preferred

realities. New York: Norton.

Gordon, L. P., & Shaffer, S. M. (2004). Mom, can I move back in with you? A survival guide

for parents of twenty some things. New York: Tarcher.

Grossman, L. (2005). Grow up? Not so fast. Time. January, pp. 42-54.

Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence, its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology,

sociology, sex, crime, religion and education. New York: Appleton.

Infoplease. (2000-2005). Household and family statistics. Retrieved October 13, 2005 from

http://wwwinfoplease.com/ipa/A0922218 htm],

Jonsson, B. (1994). Youth life projects and modernization in Sweden: A cross-sectional

study. San Diego, CA: The Society for Research on Adolescence.

Kamenetz, A. (2005). Rich little ‘poor’ kids. Village Voice. Retrieved November 2005, from

http://www. villagevoice.com/news/0530,kamenetz,66195,6.html.

Larson, R. W. (1990). The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend

alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review, 10, 155-183.

Levinson, D. J. (1986). A conception of adult development. American Psychologist, 41, 3-13.

McNamee, S. (2002). Reconstructing identity: The communal construction of crisis. In S.

McNamee & K. J. Gergen (Eds.), Therapy as social construction (pp. 186-199). London: Sage.

Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 672-682.

Mills, M., & Blossfeld, H. (2003). Globalization, uncertainty and changes in early life courses.

Springerlink, 6(2), 188-218.

Mintel Report. (2004). Lifestyles of young adults. Chicago: Mintel International Group, Ltd.

Montemayor, R., Brown, B., & Adams, G. (1985). Changes in identity status and

psychological adjustment after leaving home and entering college. Toronto, Canada: Society

for Research on Child Development.

National Marriage Project. (2000). Sex without strings, relationships without rings: Today’s

singles talk about mating and dating. Retrieved February 17, 2008, from

http://marriage.rutgers.edu/Publications/Print/ Print%20SEX %20WITHOUT

%20STRINGS.htm.

O'Hanlon, B., & Bertolino, B. (1998). Even from a broken web: Brief, respectful solution-

oriented therapy for sexual abuse and trauma, New York: Wiley.

Robbins, A. (2004). Conquering your quarterlife crisis: Advice from twentysomethings who

have been there and survived. New York: Berkeley Group.

Robbins, A., & Wilner, A. (2001) Quarter life crisis: The unique challenges of life in your

twenties. New York: Tarcher/Putnam.

Seeman, M. (1976). On the meaning of alienation. In L. A. Coser & B. Rosenberg (Eds.),

Sociological theory (pp. 401-414). New York: MacMillan.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. (1976). The anomie of affluence: A post-Mertonian conception. The

American Journal of Sociology, 82(2), 356-378.

Taffel, R. (2001). The second family. New York: St Martin’s Press.

U.S, Census Bureau. (2003). American community survey summary tables. American Fact

Finder, Tables P004. POOS.

Walsh, F. (1998). Strengthening family resilience. New York: Guilford Press.

Waterman, A. (1982). Identity development from adolescence to adulthood: An extension

of theory and a review of research. Developmental Psychology, 18, 341-358.

Watts, A. (1972). The art of contemplation. New York: Pantheon Books.

Watzlawick, P. (1978). The language of change: Elements of therapeutic communication.

New York: Norton.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: W.W.

Norton.

World Youth Report. (2003). Young people in a globalizing world. Retrieved July 15, 2006,

from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unyin/wyr03 htm.

Zimmerman, J., & Dickerson, V. (1994). Using a narrative metaphor: Implications for theory

and clinical practice. Family Process, 33(3), 233~245,

Q Springer Copyright of Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal is the

property of Springer Science & Business Media B.V. and its content may not be copied or

emailed to multiple sites or

posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However,

users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Abpsy - Prelim ReviewerDocument31 pagesAbpsy - Prelim Reviewerdharl sandiegoNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia, Neurodevelopmental & Neurocognitive DisordersDocument11 pagesSchizophrenia, Neurodevelopmental & Neurocognitive DisordersSyndell PalleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 History of Abnormal Psychology PDFDocument49 pagesChapter 1 History of Abnormal Psychology PDFGabriel Jeremy OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Code of EthicsDocument10 pagesCode of Ethicsgee wooNo ratings yet

- Psychological Evaluation Report SummaryDocument4 pagesPsychological Evaluation Report SummaryJan Mari MangaliliNo ratings yet

- Theories of Personality PRELIMSDocument10 pagesTheories of Personality PRELIMSANDREA LOUISE ELCANONo ratings yet

- Abpsy Lecture Chapter 1.1 - 2Document4 pagesAbpsy Lecture Chapter 1.1 - 2Tracey GoldNo ratings yet

- Theories of PersonalityDocument39 pagesTheories of PersonalityGene Ann ParalaNo ratings yet

- ABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY - Reviewer PrelimsDocument5 pagesABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY - Reviewer PrelimsSHIELA SAMANTHA SANTOSNo ratings yet

- Megono Rolls Article ReviewDocument5 pagesMegono Rolls Article ReviewMARIA AYUDIA ANINDHITANo ratings yet

- Experimental Psychology Flexys Syllabus 2021Document8 pagesExperimental Psychology Flexys Syllabus 2021Lovely MelgarNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Ni MonayDocument20 pagesReviewer Ni MonayDave Matthew LibiranNo ratings yet

- AbPsych Reviewer 3Document18 pagesAbPsych Reviewer 3Syndell PalleNo ratings yet

- The Mental Status ExaminationDocument16 pagesThe Mental Status Examinationeloisa.abcedeNo ratings yet

- Increasing Efficiency of Solar PanelsDocument5 pagesIncreasing Efficiency of Solar PanelsMahmudul Hasan RosenNo ratings yet

- Handouts of Experimental Psychology (PSYP402) 1-30 in PDFDocument297 pagesHandouts of Experimental Psychology (PSYP402) 1-30 in PDFSpy RiderNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis PDFDocument42 pagesChapter 3 Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis PDFGabriel Jeremy OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Developmental Science: Theories, Domains, and InfluencesDocument16 pagesDevelopmental Science: Theories, Domains, and InfluencesKat ChanNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Photoelectric Conversion Efficiency of Solar Panel by WatercoolingDocument5 pagesEnhancing Photoelectric Conversion Efficiency of Solar Panel by WatercoolingskrtamilNo ratings yet

- Filipino PsychologyDocument33 pagesFilipino PsychologyJirah MarcelinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Conceptualizing Abnormal Psychology PDFDocument67 pagesChapter 2 Conceptualizing Abnormal Psychology PDFGabriel Jeremy OrtegaNo ratings yet

- CS Psy Psy118 Bertulfo - D F 2018 2 PDFDocument8 pagesCS Psy Psy118 Bertulfo - D F 2018 2 PDFALEJANDRO RAMON CESAR MAGNONo ratings yet

- Industrial Psychology Module 2022 ZANEDocument58 pagesIndustrial Psychology Module 2022 ZANEKeanna Mae DumaplinNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus Abnormal Psychology - Winter 2014Document5 pagesCourse Syllabus Abnormal Psychology - Winter 2014payne4No ratings yet

- INTROPSY Reviewer (Book-Based Only) Chapters 1-2Document12 pagesINTROPSY Reviewer (Book-Based Only) Chapters 1-2RAYNE BERNADETTE BALINASNo ratings yet

- Social PsychologyDocument27 pagesSocial PsychologyFathima MusfinaNo ratings yet

- P110 - Module 7Document9 pagesP110 - Module 7Mariella MarianoNo ratings yet

- MA Psychological Testing Syllabus 2019-2020Document8 pagesMA Psychological Testing Syllabus 2019-2020Jam PecasalesNo ratings yet

- 10 Substance Related DisordersDocument31 pages10 Substance Related DisordersZ26No ratings yet

- Theories of PersonalityDocument30 pagesTheories of PersonalityNico Jay DauzNo ratings yet

- Stroop EffectDocument21 pagesStroop Effectjai Hind100% (1)

- Chapter 2 NotesDocument26 pagesChapter 2 NotesEsraRamosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Social Psy NotesDocument8 pagesChapter 1 Social Psy NotesNigar HuseynovaNo ratings yet

- KJGKJGKDocument6 pagesKJGKJGKSamanthaSalongaNo ratings yet

- Psych Assessment Practice TestDocument25 pagesPsych Assessment Practice TestCharlene RoqueroNo ratings yet

- Integrative Approach to Psychopathology ModelsDocument8 pagesIntegrative Approach to Psychopathology ModelsMavy QueenNo ratings yet

- Depression PresentationDocument12 pagesDepression PresentationYitzRichmond100% (1)

- ARTAPP Course OutlineDocument3 pagesARTAPP Course OutlineEmmanuel ApuliNo ratings yet

- Final Quiz 1 - Gender and SocietyDocument7 pagesFinal Quiz 1 - Gender and SocietyRadNo ratings yet

- Labovie Vief TheoryDocument9 pagesLabovie Vief TheorySai BruhathiNo ratings yet

- Motivation and EmotionDocument29 pagesMotivation and EmotionRitukumarNo ratings yet

- Midterm Examination Psych AssessmentLDocument13 pagesMidterm Examination Psych AssessmentLAnne SanchezNo ratings yet

- Psychology Lecture and Textbook NotesDocument52 pagesPsychology Lecture and Textbook NotesVictoriaNo ratings yet

- Cavite State University: CAS Thesis Form 1Document12 pagesCavite State University: CAS Thesis Form 1Kaira RazonNo ratings yet

- My Copy Understanding Abnormal PsychologyDocument12 pagesMy Copy Understanding Abnormal PsychologySYD EMERIE FAITH PARREñONo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology ReviewerDocument23 pagesAbnormal Psychology ReviewerPinca, Junea PaulaNo ratings yet

- High Efficiency Solar Cells - Sale Prices of Very High Efficiency Silicon, Multijunction Solar Cells - Green World InvestorDocument3 pagesHigh Efficiency Solar Cells - Sale Prices of Very High Efficiency Silicon, Multijunction Solar Cells - Green World InvestoralkanonimNo ratings yet

- Relevant Laws in The Practice of PsychologyDocument11 pagesRelevant Laws in The Practice of PsychologyDaegee AlcazarNo ratings yet

- Social Psychology: Social Thinking and Social InfluenceDocument60 pagesSocial Psychology: Social Thinking and Social InfluenceKerryNo ratings yet

- Io-Psych Outline-ReviewDocument2 pagesIo-Psych Outline-ReviewfaizaNo ratings yet

- PSYCH 1.1A Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic DisorderDocument28 pagesPSYCH 1.1A Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic DisorderZaza100% (1)

- Representation and Organization of Knowledge in MemoryDocument44 pagesRepresentation and Organization of Knowledge in MemoryBrylle Deeiah100% (1)

- PSY 307 Midterm Examination Reviewer Chapters 1 3Document13 pagesPSY 307 Midterm Examination Reviewer Chapters 1 3Yana TemplanzaNo ratings yet

- Biopsych Trans Chap 2Document13 pagesBiopsych Trans Chap 2Chantelle SiyNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For 2011 Campus ElectionsDocument5 pagesGuidelines For 2011 Campus ElectionsJun Rangie ObispoNo ratings yet

- Inventory SKDocument3 pagesInventory SKRodelio Paner Sr.100% (1)

- Intro Social Psyc 1Document52 pagesIntro Social Psyc 1PranavNo ratings yet

- Arnett J.J. 2007 - Emerging AdulthoodDocument6 pagesArnett J.J. 2007 - Emerging AdulthoodKarin Hanazono100% (1)

- Introduction To The Section: Ageism - Concept and Origins: Liat Ayalon and Clemens Tesch-RömerDocument10 pagesIntroduction To The Section: Ageism - Concept and Origins: Liat Ayalon and Clemens Tesch-RömerArepa TrinindoNo ratings yet

- Readings in Sociology 1 SOCIOLOGY OF AGING 1Document5 pagesReadings in Sociology 1 SOCIOLOGY OF AGING 1Kingred EnarioNo ratings yet

- Vgotsky's Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive DevelopmentDocument5 pagesVgotsky's Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive DevelopmentEmmanuel YuNo ratings yet

- CHILDHOOD1Document6 pagesCHILDHOOD1wilbertNo ratings yet

- Effect of academic anxiety on mental health of adolescentsDocument111 pagesEffect of academic anxiety on mental health of adolescentssai projectNo ratings yet

- Arnett, Emerging AdulthoodDocument281 pagesArnett, Emerging AdulthoodFrancis GayobaNo ratings yet

- Transcultural Perspective in The Nursing Care of AdultsDocument4 pagesTranscultural Perspective in The Nursing Care of AdultsMary Margarette Alvaro100% (1)

- Tratamiento Tdah y TodDocument6 pagesTratamiento Tdah y TodPatricia Ramirez BarreraNo ratings yet

- Development Stages in Middle and Late AdDocument76 pagesDevelopment Stages in Middle and Late AdGelli Ann RepolloNo ratings yet

- Session 1 - Life Cycle and Goal Setting - FinalDocument5 pagesSession 1 - Life Cycle and Goal Setting - FinalClaudia Digma100% (1)

- Aprendizaje e Identidad El Papel de La Educación Formal en La Construcción de Las Identidades.Document64 pagesAprendizaje e Identidad El Papel de La Educación Formal en La Construcción de Las Identidades.Anonymous nxk3qhNo ratings yet

- Childhood QADocument3 pagesChildhood QAKuber PatidarNo ratings yet

- Health - ModuleDocument23 pagesHealth - ModuleRegie G. Galang100% (1)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionFrom EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (89)

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityFrom EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsFrom EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (386)

- The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveFrom EverandThe Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (383)