Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CH 171

Uploaded by

EJ RaveloOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CH 171

Uploaded by

EJ RaveloCopyright:

Available Formats

A PARTICULAR SCENARIO

Our financial planning model now reminds us of one of those good news–bad news jokes.

The good news is we’re projecting a 25 percent increase in sales. The bad news is that this

isn’t going to happen unless Rosengarten can somehow raise $565 in new financing.

This is a good example of how the planning process can point out problems and potential

conflicts. If, for example, Rosengarten has a goal of not borrowing any additional funds

and not selling any new equity, then a 25 percent increase in sales is probably not feasible.

If we take the need for $565 in new financing as given, we know that Rosengarten has

three possible sources: short-term borrowing, long-term borrowing, and new equity. The

choice of some combination among these three is up to management; we will illustrate only

one of the many possibilities.

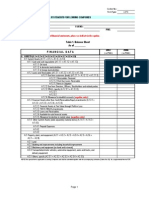

Suppose Rosengarten decides to borrow the needed funds. In this case, the firm might

choose to borrow some over the short term and some over the long term. For example,

current assets increased by $300, whereas current liabilities rose by only $75. Rosengarten

could borrow $300 − 75 = $225 in short-term notes payable and leave total net working

capital unchanged. With $565 needed, the remaining $565 − 225 = $340 would have to

come from long-term debt. Table 4.5 shows the completed pro forma balance sheet for

Rosengarten. Although it is common to assume that assets constitute a fixed percentage of revenue, this assumption

may not be correct.

In many circumstances, it is appropriate. It's worth noting that we essentially assumed Rosengarten.

since any rise in revenue resulted in an increase in fixed asset utilization.

Fixed assets rise. There would be some slack or extra capacity in most businesses.

and possibly an extra shift could be added to improve production.

The assumption that assets are a fixed percentage of sales is convenient, but it may not be

suitable in many cases. In particular, note that we effectively assumed that Rosengarten

was using its fixed assets at 100 percent of capacity because any increase in sales led to an

increase in fixed assets. For most businesses, there would be some slack or excess capacity,

and production could be increased by perhaps running an extra shift.

For example, in July 2016, Fiat Chrysler announced that it would spend $1.05 billion

in assembly plants in Ohio and Illinois to expand production of its Jeep product line. Later

that year, Ford announced plans to close two Mexican plants. Ford also announced that

it would idle four of its plants for a week, or longer. Evidently Ford had excess capacity,

whereas Fiat Chrysler did not.

In another example, in November 2016, automotive replacement parts manufacturer

Standard Motor Products announced that it was closing a plant in Texas. The company

stated that it would increase production at other plants to compensate for the closings.

Apparently,

Standard Motor had significant excess capacity at its production facilities.

Overall, according to the Federal Reserve, capacity utilization for U.S. manufacturing

companies in September 2017 was 76.2 percent, up slightly from the 76.1 percent in the

You might also like

- IB Interview Guide, Module 3: Deal Discussion Example - ADT (Leveraged Buyout)Document3 pagesIB Interview Guide, Module 3: Deal Discussion Example - ADT (Leveraged Buyout)Sofia MouraNo ratings yet

- Exercise Answers - Consolidated FS - Statement of Comprehensive IncomeDocument6 pagesExercise Answers - Consolidated FS - Statement of Comprehensive IncomeJohn Philip L Concepcion50% (2)

- A Complete Landscaping Company Business Plan: A Key Part Of How To Start A Landscaping BusinessFrom EverandA Complete Landscaping Company Business Plan: A Key Part Of How To Start A Landscaping BusinessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Mergers and Acquisitions Notes MBADocument24 pagesMergers and Acquisitions Notes MBAMandip Luitel100% (1)

- Tugas FM-High Rock IndustryDocument5 pagesTugas FM-High Rock IndustryAnggit Tut PinilihNo ratings yet

- The Five Types of Successful AcquisitionsDocument7 pagesThe Five Types of Successful AcquisitionsConsulter TutorNo ratings yet

- Course 7: Mergers & Acquisitions (Part 1) : Prepared By: Matt H. Evans, CPA, CMA, CFMDocument18 pagesCourse 7: Mergers & Acquisitions (Part 1) : Prepared By: Matt H. Evans, CPA, CMA, CFMAshish NavadayNo ratings yet

- Soal Latihan BVADocument35 pagesSoal Latihan BVAIkhsan Uiandra Putra SitorusNo ratings yet

- Discounted Cash Flow Analysis: by Ben McclureDocument17 pagesDiscounted Cash Flow Analysis: by Ben McclureresearchanalystbankingNo ratings yet

- Chapter 17 Financial Planning and ForecastingDocument39 pagesChapter 17 Financial Planning and ForecastingYu BabylanNo ratings yet

- Diageo CaseDocument5 pagesDiageo CaseMeena67% (9)

- Correction of Errors PDFDocument7 pagesCorrection of Errors PDFKylaSalvador0% (2)

- Capstone Round 3Document43 pagesCapstone Round 3Vatsal Goel100% (1)

- Play Time Toy CompanyDocument4 pagesPlay Time Toy CompanychungdebyNo ratings yet

- High Performance Tire Case StudyDocument5 pagesHigh Performance Tire Case StudyPreet AnandNo ratings yet

- Flash Memory CaseDocument6 pagesFlash Memory Casechitu199233% (3)

- Diageo Case Write UpDocument10 pagesDiageo Case Write UpAmandeep AroraNo ratings yet

- A Complete Mowing & Lawn Care Business Plan: A Key Part Of How To Start A Mowing BusinessFrom EverandA Complete Mowing & Lawn Care Business Plan: A Key Part Of How To Start A Mowing BusinessNo ratings yet

- Sample Problems On DepreciationDocument7 pagesSample Problems On DepreciationJoshua Phillip Austero Federis100% (1)

- The Upside (Review and Analysis of Slywotzky and Weber's Book)From EverandThe Upside (Review and Analysis of Slywotzky and Weber's Book)No ratings yet

- Business Plans that Win $$$ (Review and Analysis of Rich and Gumpert's Book)From EverandBusiness Plans that Win $$$ (Review and Analysis of Rich and Gumpert's Book)No ratings yet

- Advanced Financial Reporting - Class NotesDocument321 pagesAdvanced Financial Reporting - Class NotesJohn Kimiri Njoroge50% (2)

- Reading and Writing 4th QuarterDocument10 pagesReading and Writing 4th QuarterEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Case 06 NotesDocument4 pagesCase 06 NotesUmair Mushtaq SyedNo ratings yet

- Toy World Inc. Case AnalysisDocument6 pagesToy World Inc. Case AnalysisAnonymous EBlYNQbiMyNo ratings yet

- Zook On The CoreDocument9 pagesZook On The CoreThu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Top 5 PositionsDocument15 pagesTop 5 PositionsPradeep RaghunathanNo ratings yet

- Business Expansion: Example # 1 Overall Analysis of Proposed U.S. ExpansionDocument10 pagesBusiness Expansion: Example # 1 Overall Analysis of Proposed U.S. ExpansionrgaeastindianNo ratings yet

- Exhibit 4-5 Chan Audio Company: Current RatioDocument35 pagesExhibit 4-5 Chan Audio Company: Current Ratiofokica840% (1)

- Colgate Palmolive AnalysisDocument5 pagesColgate Palmolive AnalysisprincearoraNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis: Learning ObjectivesDocument39 pagesFinancial Analysis: Learning ObjectivesKeith ChandlerNo ratings yet

- Stock Whyyys 3Document101 pagesStock Whyyys 3depressionhurtsmeNo ratings yet

- JPM - Staples - Sep 2012Document10 pagesJPM - Staples - Sep 2012KunalNo ratings yet

- Summary Ross Chapter 4Document5 pagesSummary Ross Chapter 4Akun 19 LKSNo ratings yet

- Group 2 - CaseStudy Bigger Isnt Always Better - FINMA1 - BDocument14 pagesGroup 2 - CaseStudy Bigger Isnt Always Better - FINMA1 - BAccounting 201No ratings yet

- Timing Is Everything - Abello, Boteros, Polanco, SevaDocument9 pagesTiming Is Everything - Abello, Boteros, Polanco, SevaMarian Augelio PolancoNo ratings yet

- Ufa#Ed 2#Sol#Chap 06Document18 pagesUfa#Ed 2#Sol#Chap 06api-3824657No ratings yet

- Going Concern ConceptDocument2 pagesGoing Concern ConceptSavin AdhikaryNo ratings yet

- 2017 q3 Cef Investor LetterDocument6 pages2017 q3 Cef Investor LetterKini TinerNo ratings yet

- FinanceDocument3 pagesFinanceVũ Hải YếnNo ratings yet

- DCF - InvestopediaDocument16 pagesDCF - Investopediamustafa-ahmedNo ratings yet

- Divestment StrategyDocument3 pagesDivestment StrategyTenzin OzilNo ratings yet

- How To Start A Hedge Fund and Why You Probably ShouldntDocument20 pagesHow To Start A Hedge Fund and Why You Probably ShouldntJohn ReedNo ratings yet

- Tipton Ice Cream 1Document6 pagesTipton Ice Cream 1Aleksander JelskiNo ratings yet

- Corporate Mergers & Restructuring: Final Take-Home ExamDocument7 pagesCorporate Mergers & Restructuring: Final Take-Home ExamMegazzethNo ratings yet

- Artko Capital 2016 Q2 LetterDocument8 pagesArtko Capital 2016 Q2 LetterSmitty WNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Prospective Analysis: ForecastingDocument10 pagesChapter 6 Prospective Analysis: ForecastingSheep ersNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Law KingDocument5 pagesCase Study - Law KingPavi Antoni Villaceran100% (1)

- USMO White Paper (Updated)Document3 pagesUSMO White Paper (Updated)ContrarianIndustriesNo ratings yet

- Making Trade Offs in Corporate Portfolio DecisionsDocument10 pagesMaking Trade Offs in Corporate Portfolio DecisionsJohn evansNo ratings yet

- Delta Beverages Case Group 3Document7 pagesDelta Beverages Case Group 3Ayşegül YildizNo ratings yet

- Godrej Financial AnalysisDocument16 pagesGodrej Financial AnalysisVaibhav Jain100% (1)

- Transcription Doc Improving LiquidityDocument6 pagesTranscription Doc Improving Liquiditymanoj reddyNo ratings yet

- GuessDocument87 pagesGuessharsh1881100% (1)

- Basic Concepts: M & A DefinedDocument23 pagesBasic Concepts: M & A DefinedChe DivineNo ratings yet

- Analysis and InterpretationDocument3 pagesAnalysis and InterpretationKshitishNo ratings yet

- Five Questions For Dividend-Hungry InvestorsDocument5 pagesFive Questions For Dividend-Hungry InvestorsihopethisworksNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument8 pagesPDFSamantha Marie ArevaloNo ratings yet

- 15分鐘告訴你回報率在15%或更多的保險類股票Document15 pages15分鐘告訴你回報率在15%或更多的保險類股票jjy1234No ratings yet

- Case BackgroundDocument5 pagesCase BackgroundKshitishNo ratings yet

- Valuing Young or Start-Up FirmsDocument37 pagesValuing Young or Start-Up Firms000jerichoNo ratings yet

- The Well-Timed Strategy (Review and Analysis of Navarro's Book)From EverandThe Well-Timed Strategy (Review and Analysis of Navarro's Book)No ratings yet

- A Complete Pool Supply Store Business Plan: A Key Part Of How To Start A Pool & Spa Supply BusinessFrom EverandA Complete Pool Supply Store Business Plan: A Key Part Of How To Start A Pool & Spa Supply BusinessNo ratings yet

- A Roofing Contractor Business Plan: To Start with Little to No MoneyFrom EverandA Roofing Contractor Business Plan: To Start with Little to No MoneyNo ratings yet

- A Complete Pool Construction Business Plan: To Start with Little to No MoneyFrom EverandA Complete Pool Construction Business Plan: To Start with Little to No MoneyNo ratings yet

- UCSP Reviewer LawDocument6 pagesUCSP Reviewer LawEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Research EnvironmentDocument1 pageResearch EnvironmentEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Community Profile and Baseline DataDocument7 pagesCommunity Profile and Baseline DataEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Assignment Econ EntrepDocument3 pagesAssignment Econ EntrepEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Mail Merge SampleDocument1 pageMail Merge SampleEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- CH 2Document1 pageCH 2EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Reflect Upon 1Document2 pagesReflect Upon 1EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Sports Article English High School Level Earl Justine RaveloDocument2 pagesSports Article English High School Level Earl Justine RaveloEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- CH 4Document1 pageCH 4EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Math ChallengeDocument1 pageMath ChallengeEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Abstract ResearchDocument1 pageAbstract ResearchEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- CH 3Document1 pageCH 3EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RDQRT MTweek 3Document3 pages3 RDQRT MTweek 3EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- CH 7Document1 pageCH 7EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 4 TH Mathwk 9Document4 pages4 TH Mathwk 9EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RD MAPEHWK9Document6 pages3 RD MAPEHWK9EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RD MAPEHWK3Document4 pages3 RD MAPEHWK3EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RD Mathwk 7Document4 pages3 RD Mathwk 7EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- CH 5Document2 pagesCH 5EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RD MAPEHWK6Document6 pages3 RD MAPEHWK6EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RDQRT MTWK 5Document3 pages3 RDQRT MTWK 5EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RD MAPEHWK7Document7 pages3 RD MAPEHWK7EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Daily Lessonlog Day: School Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Date/Time QuarterDocument6 pagesDaily Lessonlog Day: School Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Date/Time QuarterEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 3 RDQRT MTWK 6Document3 pages3 RDQRT MTWK 6EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDocument7 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 4THMATHWK10Document4 pages4THMATHWK10EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Daily Lessonlog Day: School Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Date/Time QuarterDocument5 pagesDaily Lessonlog Day: School Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Date/Time QuarterEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Ases Post Phil Iri 2019Document3 pagesAses Post Phil Iri 2019EJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Biology I: Multiple Choice Questions 20 Items Name: - SchoolDocument3 pagesBiology I: Multiple Choice Questions 20 Items Name: - SchoolEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- 2015.12 2016.01 Q&A P2 Eng FinalDocument32 pages2015.12 2016.01 Q&A P2 Eng FinalKxlxm KxlxmNo ratings yet

- Financial Management - Education LuckDocument11 pagesFinancial Management - Education LuckVenkataramanan SNo ratings yet

- Problem 1-1 Effect of Counterbalancing and Non-Counterbalancing ErrorsDocument3 pagesProblem 1-1 Effect of Counterbalancing and Non-Counterbalancing ErrorsandreamrieNo ratings yet

- East Hill Home Healthcare Services Was Organized On January 1Document1 pageEast Hill Home Healthcare Services Was Organized On January 1trilocksp SinghNo ratings yet

- Infosys Accounting PoliciesDocument13 pagesInfosys Accounting PoliciesNawazish KhanNo ratings yet

- Topic 3.1 - Calculating WACC: Computing The WACC-An ExampleDocument2 pagesTopic 3.1 - Calculating WACC: Computing The WACC-An ExampleAngelica MedinaNo ratings yet

- KBC BelgiaDocument2 pagesKBC BelgiaBogdan StanicaNo ratings yet

- Financial Statements and ManagementReportsDocument325 pagesFinancial Statements and ManagementReportsBOCMANAGERNo ratings yet

- Managerial Accounting JONGAY (AutoRecovered)Document24 pagesManagerial Accounting JONGAY (AutoRecovered)Jhoy AmoscoNo ratings yet

- Problem 14-1: Bonds As Trading 2005Document18 pagesProblem 14-1: Bonds As Trading 2005Yen YenNo ratings yet

- ClassSession 26 - Dell Case - HandoutsDocument43 pagesClassSession 26 - Dell Case - Handoutsdrey baxterNo ratings yet

- On OversubcriptionDocument9 pagesOn OversubcriptionAyush MehraNo ratings yet

- CA Inter FM ECO Suggested Answer Nov 2022Document27 pagesCA Inter FM ECO Suggested Answer Nov 2022Abhishant KapahiNo ratings yet

- A Study On Dividend Policy and Its Effect On Market Price of Share of Ongc LTDDocument7 pagesA Study On Dividend Policy and Its Effect On Market Price of Share of Ongc LTDtejashwini sahukarNo ratings yet

- Take Home Quiz 2Document2 pagesTake Home Quiz 2Ann SCNo ratings yet

- Different Types of Debentures and Their UseDocument10 pagesDifferent Types of Debentures and Their UseMansangat Singh KohliNo ratings yet

- 12th Accountancy Set - 1 QuestionsDocument9 pages12th Accountancy Set - 1 QuestionsKaran SinghNo ratings yet

- Sec Form LcfsDocument15 pagesSec Form LcfsMeanne Waga Salazar100% (1)

- Bab 2Document6 pagesBab 2Elsha Cahya Inggri MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Post-Class Quiz #2Document9 pagesPost-Class Quiz #2Nghi AnNo ratings yet

- Answer (A) Indirect MethodDocument2 pagesAnswer (A) Indirect MethodKyriye OngilavNo ratings yet

- CH 9 Lecture NotesDocument14 pagesCH 9 Lecture NotesraveenaatNo ratings yet

- Bochungtu TV2Document6 pagesBochungtu TV23351Lương Vũ Quỳnh NhưNo ratings yet

- Corporate Financing and The Six Lessons of Market EfficiencyDocument24 pagesCorporate Financing and The Six Lessons of Market EfficiencyFelix Owusu DarteyNo ratings yet