Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Experiences of Adults With

Uploaded by

Asish DasOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Experiences of Adults With

Uploaded by

Asish DasCopyright:

Available Formats

ARTICLE

The experiences of adults with

learning disabilities attending a

sexuality and relationship group:

“I want to get married and have kids”

Matthew Box,1 Jill Shawe2

1

Specialist Practitioner – ABSTRACT

Community Learning Disabilities Background People with learning disabilities are KEY MESSAGE POINTS

Nursing, Department of Learning

Disabilities, Surrey and Borders frequently denied or restricted in their right to

Partnership NHS Foundation express their sexuality by restrictive policies, ▸ Sexuality and relationship groups can

Trust, Kingsfield Centre, Redhill, negative attitudes or lack of awareness of their offer people with learning disabilities a

UK

2 needs. They also tend to have differing and beneficial and positive experience to

Senior Research Associate,

University College London unrecognised sexual health needs to those of the explore sexuality and relationship issues.

Institute for Women’s Health, general population. Evidence suggests that ▸ The experiences of participants attending

London, UK acquiring a greater knowledge and awareness of such a group were unique and individual.

Correspondence to sexuality and relationship issues helps to ▸ A person-centred approach needs to be

Mr Matthew Box, Department of decrease these disadvantages and to promote a adopted to improve participants’ experi-

Learning Disabilities, Surrey and greater sense of well-being for this group. ences of attending such groups.

Borders Partnership NHS Methods The experiences of eight adults with

Foundation Trust, CTPLD East,

Kingsfield Centre, Philanthropic learning disabilities attending a sexuality and

Road, Redhill RH1 4DP, UK; relationship group, based on a mixture of

matthew.box@sabp.nhs.uk validated and established sexuality and the right to express their sexuality,1 2

relationship programmes, were explored using a including the desire for same sex relation-

Received 10 October 2012

Revised 10 April 2013 case study approach. Participants’ experiences ships.3 Although attitudes are changing,

Accepted 23 April 2013 were gathered through semi-structured they still experience difficulties in expres-

Published Online First interviews and analysed using qualitative content

20 June 2013 sing their sexuality4–6 and in developing

analysis supported by participant observation and meaningful relationships.1 They also

pre- and post-group assessment of knowledge. tend to have differing and unrecognised

Results Participant experiences were unique and sexual health needs to those of the

individual, with few shared opinions. All general population.7 8 They require more

participants demonstrated increases in their total support, including sexual health promo-

knowledge scores in the post-group assessment tion, for their needs to be met.9

and felt that attending the group had changed The term ‘learning disability’ in this

their views on relationships; they felt that they article relates to a significant impairment

were more able to talk to others, to trust of intelligence (IQ score below 70) and

someone, to feel confident to want longer social function, which commenced before

relationships and to be married with children. adulthood and which is life-long.10 The

Conclusions Sexuality and relationship groups degree of learning disability can be

can offer participants a beneficial and positive further subdivided into mild, moderate,

experience to explore such issues. The severe and profound.10 People with learn-

experiences of participants could be enhanced ing disabilities may also have other

through adopting a person-centred approach co-morbid diagnoses (e.g. Down’s syn-

and through recognising that participants have drome, autism, physical disabilities,

individual experiences that may not be shared neurological and mental health disor-

within the group environment. ders), which are not always formally

diagnosed.

To cite: Box M, Shawe J. INTRODUCTION As a result of past and present atti-

J Fam Plann Reprod Health Historically people with learning disabil- tudes, people with learning disabilities

Care 2014;40:82–88. ities have been denied and restricted in are often reluctant to develop their

82 Box M, et al. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014;40:82–88. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100509

Article

sexual lives.4–6 Structural and organisational problems changes in individuals’ attitudes towards their sexual-

restrict relationships from forming and/or develop- ity4 32 and to that of their carers.34 People with learn-

ing,1 contributing to social isolation11 and small social ing disabilities therefore need to be provided with

networks.2 These individuals have fewer opportunities meaningful sexuality and relationship education that

to engage in consenting sexual relationships12 and are reflects their unique needs.35

less likely to develop positive experiences in their This study aimed to build upon the evidence base

sexual lives.13 regarding the sexuality and relationship needs of

As a consequence of these attitudes and experiences, people with learning disabilities, through exploring

many people with learning disabilities feel that they their experiences of attending a sexuality and relation-

have a lack of privacy in society,14 15 thinking that ship group. In particular it aimed to discover what

they are constantly being monitored and judged. participants liked and did not like about the group,

Hingsburger and Tough14 describe how a couple think how attendance at the group made participants feel,

they cannot have sex in their bedroom as “we’d get and how it affected their views and feelings about sex

killed”, and instead engage in intimate behaviour in and relationships. The aim was to improve and tailor

the park as it is seen as somewhat private and safe, the facilitation of future groups to meet the needs of

and away from staff and others who might punish participants.

them.

Many parents are also reticent for people with METHODS

learning disabilities to engage in sexual relation- The study used case study methodology36 following a

ships.16 Despite normally recognising this as their qualitative theoretical perspective to explore the

right17 they are fearful of their vulnerability.18 Indeed experiences of adults with learning disabilities attend-

numerous parents still support sterilisation as a form ing a sexuality and relationship group. Data were pri-

of contraception,4 especially as they do not trust their marily obtained from semi-structured interviews and

child to use reversible contraception and they fear supported by participant observation and assessment

that pregnancy might result from sexual abuse.18 of pre- and post-group knowledge. Participants for

This concern is justified, as people with learning the study were recruited from adults referred to the

disabilities are at high risk of experiencing sexual Community Team for People with Learning

abuse,19 either as victims or as perpetrators. This may Disabilities (CTPLD) requesting sexuality and relation-

be due to their lack of knowledge regarding capacity ship input. The CTPLD is a National Health Service

to consent and the law,20 their vulnerability,7 21 (NHS) organisation, commissioned to work with any

limited sexuality and relationship education13 and lack adult with a learning disability requiring specialist

of adequate policies.22 There is a higher rate of abuse health input. Referrals can be made by anyone and

for women with learning disabilities compared to can include self-referrals.

men, and nearly all the perpetrators are men who Ethical approval was obtained from Surrey Research

themselves have a learning disability.23 Ethics Committee and the local NHS Trust.

People with learning disabilities have also been The researcher approached participants only when

shown to have decreased levels of knowledge and it was agreed by professionals within the CTPLD that

understanding of sexuality and relationship issues24 the individual’s needs could be appropriately met

and fewer sexual experiences25 compared to the through attendance at a sexuality and relationship

general population. They are less likely to be offered group. As the study explored a vulnerable group’s

sexual health screening26 and are more likely to experience of a sensitive subject, special consideration

engage in unsafe sex.27 was given to the ethics of conducting the research and

Many parents and carers are fearful that providing obtaining informed consent from participants. This

sexuality and relationship information for people with followed advice from the British Psychological

learning disabilities will lead to unwanted sexualised Society’s Professional Practice Board37 in relation to

behaviours28 and will evoke feelings of discomfort.5 17 the Mental Capacity Act,38 as well as guidance from a

In contrast, many people in society1 5 17 and many clinical psychologist and speech and language therap-

health professionals29 view people with learning dis- ist from the CTPLD. A participant information sheet

abilities as asexual and consequently not needing and consent form were devised in an easy-to-read

sexual health promotion. format covering all aspects needed to display

Recognition of the need for, and benefits of, sexual- informed consent.

ity and relationship education for people with learn- Prior to the group starting, participants met with

ing disabilities has been demonstrated to support the researcher (who was also the male facilitator of

them in developing their needs.9 30 This is further the group) to discuss the topics the group intended to

promoted by reports of group programmes31–33 that cover and to assess what participants hoped to get out

have been facilitated to help achieve this; these led to of attending the group. A social and sexual knowledge

increases in knowledge,34 decreases in incidences of assessment39 was also completed. This is a standar-

inappropriate sexualised behaviour,34 and positive dised questionnaire containing 111 questions over 16

Box M, et al. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014;40:82–88. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100509 83

Article

sections. During this visit the researcher discussed completed, after which semi-structured interviews

what participation in the research study involved, were conducted at a subsequent meeting. Both of these

namely observations within the group and a recorded typically lasted 1 hour, and took place without carers

interview of their experiences of the group. It was being present. Interviews followed a topic guide and

stressed that if group members did not wish to partici- used open-ended questions, to reduce acquiescence.43

pate in the study, this would not affect their attend- Pictures were also used as prompts to address commu-

ance at the group. Participants were then visited at nication difficulties and help participants remember

least 24 hours later to complete the consent form, different aspects of the group.43 Participants were

which was completed in the presence of a person encouraged to discuss issues and experiences pertinent

independent of the study (e.g. carer) to ensure that to themselves. The interviews were recorded and tran-

there was no duress or coercion. This allowed partici- scribed verbatim and analysed using qualitative content

pants time to weigh up the information, demonstrate analysis.44 This involves the analysis of transcribed

they were able to retain information and decide if speech and takes into account how words are said (e.g.

they wished to participate. repetition, elaborative speech). Transcripts are analysed

Participants were informed that the research study by repeatedly reading through them for any themes

would be confidential, but that if they disclosed any- that emerge and identifying any substantive statements,

thing that might indicate a safeguarding concern, this which are categorised. Emergent themes are then

would be reported to the relevant authorities. placed on a grid for thematic analysis.

The sexuality and relationship group met for ten

weekly 2-hour sessions at a local day centre for adults RESULTS

with learning disabilities. The sessions were Group participants

co-facilitated by a male and a female Learning A profile of the participants who took part in the

Disability Community Nurse from the CTPLD, with study is shown in Table 1. The CTPLD is based in an

past experience of running sexuality and relationship area that is not ethnically diverse and so participants’

groups. Two participants (P2 and P3) were previously ethnicity reflects the lack of diversity in the local

known to the researcher, who had completed an population. Participant diagnosis was obtained from

assessment of their health needs when they were psychiatric, social and medical records. Although P2

referred to the CTPLD. None of the participants were had no formal diagnosis, from the researcher’s own

previously known to the female facilitator. experience it was evident that he displayed autistic

Sessions were based on validated and established sexu- tendencies. None of the participants in the group

ality and relationship programmes for people with learn- were engaged in paid employment and all received

ing disabilities.40–42 Topics included: basic anatomy and benefits as their means of income, which is typical for

body differences, puberty, hygiene, menstruation, meno- the vast majority of adults with learning disabilities.11

pause, sexual activities including same-sex relationships, The group consisted of six regular participants

conception, contraception and safe sex including abstin- (three females and three males), and one female and

ence, masturbation, wet dreams, self-examination, attrac- one male who only attended two sessions each. These

tions, different types of relationships, forming and two participants were experiencing personal difficul-

managing relationships, emotions, attitudes including ties (e.g. bereavement) when the group ran and there-

stereotyping, good and bad touch, consent, public and fore requested to attend the next group. One of the

private places, abuse and assertiveness. regular group participants was unable to demonstrate

Participant observation was undertaken by facilita- capacity to give valid consent and was therefore not

tors to capture group interaction and behaviour, included in the study.

content of language, knowledge and understanding,

emotional experiences, and session events. Social and sexual knowledge assessment

Following the final session, individual and group All study participants demonstrated increases in their

social and sexual knowledge assessments39 were total knowledge in the post-group assessments (Table 2).

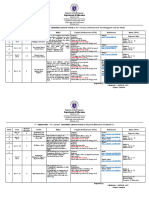

Table 1 Participants’ profiles

Participant

Attribute P1 P2 P3 P4 P5

Gender Male Male Male Female Female

Age (years) 20–24 45–49 20–24 30–34 25–29

Ethnicity White British White Other White British White British White British

Diagnosis Moderate LD, autism Mild LD, cerebral palsy Mild LD, Asperger Mild LD, epileptic Moderate LD, paranoid

syndrome, ADHD schizophrenia, depressive disorder

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; LD, learning disability.

84 Box M, et al. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014;40:82–88. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100509

Article

Table 2 Participants’ pre- and post-group social and sexual knowledge scores

Participant

Parameter P1 P2 P3 P4 P5

Assessment Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post

Total score 55/111 70/111 80/111 98/111 92/111 99/111 93/111 98/111 49/111 63/111

Score change +15 +18 +7 +5 +14

Participants who had a lower pre-group score available if needed. Both participants appreciated this:

achieved a larger number of correct answers in their “I feel like I’d have liked to have a support worker

post-group assessment scores. Participants generally there anyway just to make sure but, mm, now I’ve

had better knowledge of social aspects of the assess- done it on my own and they go next door just to make

ment (social behaviour: kissing and sexual assault; sure that … I’m glad I did it anyway”. [P4]

marriage and caring for children), and tended to not Most of the participants felt that the group was

score as well in the sexual knowledge sections about the right size and that the group benefited from

(masturbation, menstruation and contraception). In being mixed gender. They enjoyed sharing the experi-

particular the only form of contraception most partici- ence with other group members and some participants

pants were aware of was the condom, despite different formed close relationships, feeling supported by one

forms of contraception being covered in the sessions. another. “It’s easier to learn things with different

The quality of responses to questions also tended to kinds of people.” [P2] “It was really quite cool having

improve in the post-group assessments, with partici- men and women in the group.” [P5]

pants giving more detailed answers. As expected, One participant would have preferred an all-male

participants with a mild learning disability achieved group, suggesting he feels more comfortable in an

higher scores than participants with a moderate learn- all-male environment: “Because men are more, [...] I

ing disability. mean they are different, you know, to women”. [P1]

Participants with milder learning disabilities appeared

Sexuality and relationship group assessment to benefit from having people with more significant

Participants’ individual post-group assessment learning disabilities present as they tended to be more

responses were largely positive and similar to their open about their feelings and they felt that they could

responses as a group, stating that they liked meeting help each other. “I suppose it felt comfortable ‘cos

new people and being around people. Participants erm … unlike other people, they don’t hide if they

tended not to have negative comments except P2 who don’t understand everything, they don’t pretend.” [P2]

found the group too noisy and busy. “It made me feel proud actually … I felt I could help

others … And it felt good….” [P4]

Semi-structured interviews Participants generally commented favourably about

Previous experience of sexuality and relationship education the organisation, venue and time of the group but felt

The participants could not recall having had any sig- that it was very important to have consistent group

nificant sexuality and relationship education before facilitation. When one facilitator was replaced for two

attending the group, apart from P3 who remembered sessions by another female facilitator the group felt

having input at school, “They just talked about differ- disrupted. “Sometimes if they were different you start

ent [contraceptives] … like condoms, not much else”, all over again … because people don’t know what we

and P4 who had been visited by someone at home. have talked about.” [P2]

Participants appeared to have preferred the group

Experience of participating in the sexuality and relationship group being facilitated by a male and female together,

Participants’ general experience of the group was feeling this added to the overall experience and if they

positive, with most participants feeling nervous and had something personal they wanted to discuss they

scared before they attended their first session, being would talk to a facilitator of the same sex privately: “I

uncertain about what was going to happen and who have to go to a lady if I wanted someone to talk to

would be there, but glad that they attended, feeling someone privately”. [P4] This was in relation to dis-

happy and safe in the group: “I preferred it in a big cussing sexual attractions she had for someone, which

group … It makes me calm and safer – and safe in she later discussed within the group as a whole.

that room”. [P4]

The two female participants initially both wanted Content of programme

their support workers to attend the session with them, Participants felt that 10 sessions was about the right

but were informed that the group was a private and amount, but the male participants would have liked

confidential arena and so non-participants/observers the sessions to be longer, “as things often became

were not allowed, but could sit next door and be rushed”. [P3] The group had agreed on ground rules

Box M, et al. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014;40:82–88. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100509 85

Article

for conduct within the sessions and most participants interviews. Observations indicated that participants

felt these were beneficial. benefited from attending the group, showing

Participants in the main talked favourably about increased insight into sexuality and relationship issues

session content, and worksheets were thought to be a as the group progressed. This was shown through par-

good to aid communication. They enjoyed the more ticipants using more appropriate terminology for

participatory and energetic activities, such as the parts of their body, increasingly responding correctly

attractions exercise where participants discussed why to questions and activities and, most importantly,

people may fancy one another from pictures they had gradually feeling more able to discuss sexuality and

cut from magazines. “I felt it was great because you relationship issues.

get, you know who you like and don’t like. That way Observations also indicated that all but one partici-

you learn.” [P4] “I think it was fun.” [P5] pant enjoyed the shared experience. Participants

All participants liked using DVDs, with P1 mention- showed respect for one another and frequently

ing the DVD exploring safe sex: “That was helpful encouraged and praised each other when they did

because … for me … I could just see what that is”. something well. Participants with milder learning dis-

Participants would have liked more role play in the abilities tended to support and encourage participants

sessions. They talked about how they enjoyed dressing with more significant learning disabilities, who often

up and feeling they were relaxed, fun and more realis- lost concentration during more discussion-based exer-

tic. Although some participants said they did not cises. All participants appeared to benefit from using

enjoy role play, as they felt embarrassed, they appre- pictorial aids to support teaching, which allowed them

ciated participating, acknowledging that it was good to gain a better understanding of what was being dis-

to practise these skills: “the way we learn is to show cussed and then to formulate their thoughts.

other people”. [P5]

Participants generally preferred having the sex edu- DISCUSSION

cation sessions before the relationship sessions, as this Participants’ experiences of attending a sexuality and

helped them to better explore the more abstract rela- relationship group in this case study were unique and

tionship sessions through having a knowledge base of individual, with participants often sharing positive

sexuality topics and terminology used. experiences of one aspect of the group and not of

another. This was highlighted in the semi-structured

Post-group views about sexuality and relationships interviews where participants tended to talk more

All participants felt that the group had positively about subjects important to them, which differed for

changed their views on relationships. “I now feel more each participant, and the reasons why they did or did

confident in relationships … I want [...] to be married not enjoy a particular aspect of the group also often

with children.” [P3] “I can trust someone … more differed for each participant. Although this may

able to talk to others.” [P5] suggest that it is difficult to have fixed rules in the

Participants appreciated being able to discuss sexual- facilitation of a sexuality and relationship group,

ity and relationship issues. “People always talk to me the findings from the data can assist in improving the

about a lot of things now.” [P1] Another felt he now facilitation of future groups, through adopting a more

had a better understanding regarding the rules of rela- person-centred approach.11 45 Thought should there-

tionships: “I can work out now about relationships … fore be given to changing the recruitment procedure

work out how they work”. [P2] for future groups and improving the assessment

The majority of participants stated they now felt process. This would include gathering more informa-

more confident in relationships, with P3 discussing tion of potential participants’ wants and needs before

how he now felt more assertive: “I found it hard to the course, including their past experiences of attend-

say no to people in the past”. He stressed how the ing groups and their preferred learning styles.

‘Rules for Saying No’ exercise3 allowed him to prac- However, it is acknowledged that this would be more

tise assertiveness techniques that he could transfer time consuming and there may not be sufficient

outside the group. numbers of potential participants to make up groups

Participants in general did not comment upon with similar needs.

whether the group made any difference to how they The data indicate that the general experience of the

thought about sex and their bodies, although one group was positive, which is reflected in participants’

female participant commented: “I now know my body high attendance record. The fact that the two partici-

is changing and that I can talk to someone about sex” pants who knew the researcher prior to the group did

[P4], demonstrating an awareness that bodies change not mention this in their semi-structured interviews

through ageing. would indicate that this had little significance regard-

ing their experience of the group. Participants talked

Participant observations favourably about session content, with the majority

Participant observations generally correlated with the saying they enjoyed the sessions that tended to be

views they had expressed in their semi-structured more practical. The male participants commented that

86 Box M, et al. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014;40:82–88. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100509

Article

they also enjoyed the menstruation and sexual activ- Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally

ities session, which was more discussion-based using peer reviewed.

pictures, as they had not previously explored this. The

female participants appeared comfortable discussing REFERENCES

this area with the males present. 1 Lesseliers J. A right to sexuality? Br J Learn Disabil 1999;27:

Participants enjoyed being in a mixed-gender group 137–140.

2 Carson I, Docherty D. Friendships, relationships and issues in

and learning from each other. For many participants

sexuality. In: Race D (ed.), Learning Disability – A Social

this may have been the first time they had experienced

Approach. London, UK: Routledge, 2002:139–153.

sharing intimate and personal experiences with

3 Lofgren-Martenson L. The invisibility of young homosexual

members of the opposite sex, and as such the group women and men with intellectual disabilities. Sex Disabil

was very revealing and liberating for them. This is in 2009;27:21–26.

contrast to previous literature4 32 46 that suggests that 4 Withers P, Ensum I, Howarth D, et al. A psycho educational

single-sex groups are preferable to mixed groups. group for men with intellectual disabilities who have sex with

Participants appeared to have enjoyed and benefited men. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2001;14:327–339.

from sharing the experience with other group 5 Aunos M, Feldman M. Attitudes towards sexuality, sterilization

members, speaking fondly of one another. It has been and parenting rights of persons with intellectual disabilities.

recognised that people with learning disabilities gain J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2002;15:285–296.

from being in groups through sharing their experi- 6 Thomas G, Kroese B. An investigation of students’ with mild

learning disabilities reactions to participating in sexuality

ences and listening to the opinions of other group

research. Br J Learn Disabil 2005;33:113–119.

members.7 Indeed as the group progressed, partici-

7 Sant Angelo D. Learning disability community nursing:

pants showed a greater respect for one another and addressing emotional and sexual health needs. In: Astor R,

appreciated that people have differing needs and feel- Jeffereys K (eds), Positive Initiatives for People with Learning

ings in relation to sexuality and relationships. Difficulties. Basingstoke, UK: MacMillan Press Ltd,

Although some participants still struggled with this, 2000:52–68.

the fact that they demonstrated a positive change in 8 Peate I, Maloret P. Testicular self-examination: the person with

self-awareness helps to demonstrate the positive learning disabilities. Br J Nurs 2007;16:931–935.

nature of attending a group. However, it needs to be 9 Grieveo A, McLaren S, Lindsay W. An evaluation of research

recognised that individual work would be more and training resources for the sex education of people with

appropriate for some people;7 for instance, if they moderate to severe learning disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil

2006;35:30–37.

feel uncomfortable discussing personal issues due to

10 World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of

past experiences of abuse, or if they find the proxim- Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and

ity of others distressing due to autism. Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health

Limitations of the study included the small sample Organization, 1992.

size, reducing its ability for its findings to be generalis- 11 Department of Health. Valuing People: A New Strategy for

able. In addition, the participants were all known to Learning Disability for the 21st Century. London, UK: HMSO,

the researcher as he co-facilitated the group, which 2001.

may have inhibited them in discussing negative experi- 12 Wheeler P, Jenkins R. The management of challenging sexual

ences within the interviews. However, past research behaviour. Learn Disabil Pract 2004;7:28–35.

studies interviewing people with learning disabilities 13 Ailey S, Marks B, Crisp C, et al. Promoting sexuality across the

indicate that participants feel embarrassed discussing life span for individuals with intellectual and developmental

disabilities. Nurs Clin North Am 2003;38:229–252.

sexuality issues with a stranger, and will talk more

14 Hingsburger D, Tough S. Healthy sexuality: attitudes, systems,

openly with group facilitators.4 6

and policies. Res Pract Persons Severe Disabl 2002;27:8–17.

15 Hollomotz A. ‘May we please have sex tonight?’ – people with

CONCLUSIONS learning difficulties pursuing privacy in residential group

This study, which explored the experiences of adults settings. Br J Learn Disabil 2008;37:91–97.

with learning disabilities attending a sexuality and 16 Evans D, McGuire B, Healy E, et al. Sexuality and personal

relationship group, has shown that participants’ relationships for people with an intellectual disability. Part II:

staff and family carer perspectives. J Intellect Disabil Res

experiences are unique and individual. Participants

2009;53:913–921.

indicated that their experiences were largely positive 17 McDonagh R. Too sexed-up! J Adult Prot 2007;9:27–33.

and beneficial and the future running of similar 18 Patterson-Keels L, Quint E, Brown D, et al. Family views on

groups should therefore be encouraged. sterilization for their mentally retarded children. J Reprod Med

1994;39:701–706.

Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the

participants who took part in this study, and Susann Stone who 19 McCormack B, Kavanagh D, Caffrey S, et al. Investigating

co-facilitated the group. sexual abuse: findings of a 15-year longitudinal study. J Appl

Competing interests None. Res Intellect Disabil 2005;18:217–227.

20 O’Callaghan A, Murphy G. Sexual relationships in adults with

Ethics approval Ethical approval for this study was obtained

from Surrey Research Ethics Committee and the local NHS intellectual disabilities: understanding the law. J Intellect

Trust. Disabil Res 2007;51:197–206.

Box M, et al. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014;40:82–88. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100509 87

Article

21 Bell D, Cameron L. The assessment of the sexual knowledge 33 McGaw S, Ball K, Clark A. The effect of group intervention on

of a person with severe learning disability and a severe the relationships of parents with intellectual disabilities. J Appl

communication disorder. Br J Learn Disabil 2003;31: Res Intellect Disabil 2002;15:354–366.

123–129. 34 Plunkett P. An evaluation of a community-based sexuality

22 Fyson R, Kitson D. Independence or protection – does it have education program for individuals with developmental

to be a choice? Reflections on the abuse of people with disabilities. Electron J Hum Sex 2002;5. http://www.ejhs.org/

learning disabilities in Cornwall. Crit Soc Policy volume5/plunkett/references.html [accessed 5 October 2012].

2007;27:426–436. 35 Peate I. Men’s Sexual Health. London, UK: Whurr Publishers

23 McCarthy M, Thompson D. A prevalence study of sexual Ltd, 2003.

abuse of adults with intellectual disabilities referred for sex 36 Yin R. Case Study Research. Design and Methods (4th edn).

education. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 1997;10:105–124. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2009.

24 Galea J, Butler J, Iacono T, et al. The assessment of sexual 37 British Psychological Society, Professional Practice Board.

knowledge in people with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Conducting Research With People Not Having the Capacity to

Disabil 2004;29:350–365. Consent to Their Participation. A Practical Guide for

25 McCabe M, Cummins R. The sexual knowledge, experience, Researchers. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society, 2008.

feelings and needs of people with mild intellectual disability. 38 HMSO. Mental Capacity Act. London, UK: Crown Copyright,

Educ Train Ment Retard Dev Disabil 1996;3:13–21. 2005.

26 Healthcare Commission. Performing Better? A Focus on Sexual 39 Fraser J. Not a Child Anymore. Birmingham, UK: Brook

Health Services in England. London, UK: Healthcare Publications, 1987.

Commission, 2007. 40 McCarthy M, Thompson D. Sex and the 3Rs. Rights,

27 Cambridge P. Men with learning disabilities who have sex Responsibilities and Risks. A Sex Education Package for Working

with men in public places: mapping the needs of services and with People with Learning Difficulties (Revised Edition).

users in South East London. J Intellect Disabil Res 1996;40: Brighton, UK: Pavilion, 1998.

241–251. 41 Craft A. Living Your Life: The Sex Education and Personal

28 Valenti-Hein D, Dura J. Sexuality and sexual development. In: Development Resource for Special Education Needs. London,

Jacobson J, Anton J (eds), Manual of Diagnosis and UK: Brook Publications, 2003.

Professional Practice in Mental Retardation. Washington, DC: 42 Kerr-Edwards L, Scott L. Talking Together … About Sex and

US American Psychological Association, 1996;301–310. Relationships. A Practical Resource for Schools and Parents

29 Earle S. Disability, facilitated sex and the role of the nurse. Working with Young People with Learning Disabilities. London,

J Adv Nurs 2001;36:433–440. UK: Family Planning Association, 2003.

30 Blanchett W, Wolfe P. A review of sexuality education curricula; 43 Sigelman C, Budd E, Spanhel C, et al. When in doubt, say yes:

meeting the sexuality education needs of individuals with acquiescence in interviews with mentally retarded persons.

moderate and severe intellectual disabilities. Res Pract Persons Ment Retard 1981;19:53–58.

Severe Disabil 2002;27:43–57. 44 Gillham B. Research Interviewing: The Range of Techniques.

31 Sheppard L. Growing pains: a personal development program Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press, 2005.

for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in 45 Department of Health. Valuing People Now: A New Three-Year

a specialist school. J Intellect Disabil 2006;10:121–142. Strategy for Learning Disabilities London, UK: Department of

32 Sant Angelo D. Group think. Can group work with people Health Publications, 2009.

with learning disabilities be an effective approach? Learn 46 McCarthy M. Sexuality and Women with Learning Disabilities

Disabil Res Pract 2001;3:26–28. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1999.

88 Box M, et al. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014;40:82–88. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100509

You might also like

- Greek and Latin RootsKeys To Building VocabularyDocument211 pagesGreek and Latin RootsKeys To Building VocabularyDuc Vu90% (30)

- Sex Education and Family BackgroundDocument29 pagesSex Education and Family Backgroundkimb baturianoNo ratings yet

- Ravens Progressive MatricesDocument16 pagesRavens Progressive Matricesabc123-189% (74)

- Grade 8 Health Physical EducationDocument2 pagesGrade 8 Health Physical Educationapi-364536997No ratings yet

- Social Competence: Interventions for Children and AdultsFrom EverandSocial Competence: Interventions for Children and AdultsDiana Pickett RathjenNo ratings yet

- Quantitative ResearchDocument22 pagesQuantitative ResearchElsieGrace Pedro Fabro50% (2)

- 7 Great Theories About Language Learning-1Document8 pages7 Great Theories About Language Learning-1Iqra100% (1)

- Revision Checklist ESLDocument12 pagesRevision Checklist ESLdevajlaisafNo ratings yet

- Research Final PaperDocument20 pagesResearch Final PaperJohn Carl AparicioNo ratings yet

- Social-Sexual Education in Adolescents With Behavioral Neurogenetic SyndromesDocument7 pagesSocial-Sexual Education in Adolescents With Behavioral Neurogenetic Syndromesaoi maryNo ratings yet

- Teaching AS Chemistry Practical SkillsDocument91 pagesTeaching AS Chemistry Practical SkillsArsalan Ahmed Usmani90% (20)

- ABA VB-MAPP Symposium 5-26-07Document41 pagesABA VB-MAPP Symposium 5-26-07Monalisa CostaNo ratings yet

- Prime-Hrmo Action Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesPrime-Hrmo Action Plan TemplateGing J.100% (1)

- Evaluation Clinical Practice - 2022 - Honan - Program Evaluation of An Adapted PEERS Social Skills Program in Young AdultsDocument10 pagesEvaluation Clinical Practice - 2022 - Honan - Program Evaluation of An Adapted PEERS Social Skills Program in Young Adultsnuel7No ratings yet

- Reading & Writing - Q4 - Week 3 & 4Document35 pagesReading & Writing - Q4 - Week 3 & 4Mary Jane CalandriaNo ratings yet

- Edu410 PD PlanDocument4 pagesEdu410 PD Planapi-4125669740% (1)

- Prosocial Behaviour: Prof. Ariel Knafo-Noam, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, IsraelDocument61 pagesProsocial Behaviour: Prof. Ariel Knafo-Noam, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, IsraelALMALYN ANDIHNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of Live in Partner in Senior High at Dapdap High School.Document16 pagesA Case Study of Live in Partner in Senior High at Dapdap High School.andrew100% (1)

- Severe and Multiple Disabilities-Essay On Chapter 12Document5 pagesSevere and Multiple Disabilities-Essay On Chapter 12TheHatLadyNo ratings yet

- GfjygkujDocument38 pagesGfjygkujCsr JoanaNo ratings yet

- Neurodiversity and Gender Diverse Youth - An Affirming Approach To Care - 2020Document7 pagesNeurodiversity and Gender Diverse Youth - An Affirming Approach To Care - 2020leonardooomaartinsNo ratings yet

- Growing Up Sex and RelationshipsDocument28 pagesGrowing Up Sex and RelationshipsshylajaNo ratings yet

- Home Science Project Draft Interview Two Adolescents and Two Adults Regarding Their Perception of People With Special NeedsDocument11 pagesHome Science Project Draft Interview Two Adolescents and Two Adults Regarding Their Perception of People With Special NeedsfarhaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Group 4 DraftDocument24 pagesThesis Group 4 DraftJoshyne BernalesNo ratings yet

- Sexuality Education Annotated BibliographyDocument19 pagesSexuality Education Annotated Bibliographyapi-550131693No ratings yet

- MAPEH8 - WEEK14Document14 pagesMAPEH8 - WEEK14Ligaya BacuelNo ratings yet

- Barnett 2015Document9 pagesBarnett 2015NobodyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 NeeewDocument8 pagesChapter 1 NeeewAnonymous enspv0UpNo ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument21 pagesAction ResearchMarlon SimbaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Sexuality EdDocument9 pagesThe Importance of Sexuality EdAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Perspect Sex Reprod Health 23 55 49Document13 pagesPerspect Sex Reprod Health 23 55 49natalia barriosNo ratings yet

- G6 CUF HealthEd Mar8Document4 pagesG6 CUF HealthEd Mar8angielyn concepcionNo ratings yet

- Fsie 2Document16 pagesFsie 2Rimil Joyce BalbasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 3 ThesisDocument21 pagesChapter 1 3 ThesisJohn Patriarca0% (1)

- Investigacion TeletonDocument10 pagesInvestigacion TeletonFran RubilarNo ratings yet

- Lessonplan tch210Document6 pagesLessonplan tch210api-252738288No ratings yet

- Identifying Effective Methods For Teaching Sex Education To Individuals With Intellectual Disabilities A Systematic Review PDFDocument22 pagesIdentifying Effective Methods For Teaching Sex Education To Individuals With Intellectual Disabilities A Systematic Review PDFDhandrei Justin BlancoNo ratings yet

- The Problem and It's BackgroundDocument54 pagesThe Problem and It's BackgroundRomar GomezNo ratings yet

- PR Group 8 Chapter 1 3 RevisedDocument18 pagesPR Group 8 Chapter 1 3 RevisedhtfcbqxstnNo ratings yet

- The Long-Term Impact of Early Parental DeathDocument11 pagesThe Long-Term Impact of Early Parental DeathMartynaNo ratings yet

- Attitudes Changing Report PDFDocument25 pagesAttitudes Changing Report PDFsrikar13No ratings yet

- Co-Exist Research PaperDocument49 pagesCo-Exist Research PaperharshitaNo ratings yet

- Literature MatrixDocument4 pagesLiterature MatrixgapangdaisyNo ratings yet

- Structural Social Capital of Parents Having Persons With Disability in ChandigarhDocument8 pagesStructural Social Capital of Parents Having Persons With Disability in ChandigarhIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document11 pagesChapter 1jezebeth malloryNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Sexuality Education Toolkit Trainers ManualDocument95 pagesComprehensive Sexuality Education Toolkit Trainers ManualPidot Bryan N.No ratings yet

- Considering Inclusion in Research: An Introduction To Scientific and Policy PerspectivesDocument17 pagesConsidering Inclusion in Research: An Introduction To Scientific and Policy Perspectivessaad nNo ratings yet

- Pdhpe s4 Stronger Together ProgramDocument14 pagesPdhpe s4 Stronger Together ProgramAshleigh WalkerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Theoretical Framework / Conceptual Framework: - RrlsDocument7 pagesChapter 2: Theoretical Framework / Conceptual Framework: - RrlsAron R OsiasNo ratings yet

- Signature AssignmentDocument15 pagesSignature Assignmentapi-302494416No ratings yet

- Family Health: PpcalaraDocument2 pagesFamily Health: PpcalaraCristine Ann ApuntarNo ratings yet

- Adolescents in Educational ContextsDocument6 pagesAdolescents in Educational ContextsExpertNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument8 pagesResearchArchie Dumalag GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Challenges Faced by Teachers in Teaching Sex Education in Secondary Schools in Awgu Local Government Area of Enugu StateDocument55 pagesThe Challenges Faced by Teachers in Teaching Sex Education in Secondary Schools in Awgu Local Government Area of Enugu StateNwigwe Promise ChukwuebukaNo ratings yet

- Social Work 621 Section 67334/35 and 67342/3Document24 pagesSocial Work 621 Section 67334/35 and 67342/3sachin BhartiNo ratings yet

- Chp1tochp5 Delmontecopm 1Document102 pagesChp1tochp5 Delmontecopm 1Angel Rose NarcenaNo ratings yet

- Inbound 175701145108736279Document21 pagesInbound 175701145108736279Jonalyn Arpon NaroNo ratings yet

- Supporting Gender Independent Children and Their FamiliesDocument14 pagesSupporting Gender Independent Children and Their FamiliesGender SpectrumNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Impact of Healthy Family RelationshiDocument40 pagesMeasuring The Impact of Healthy Family RelationshiDrey KimNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Assessment Intervention DisabilitiesDocument61 pagesGuidelines Assessment Intervention DisabilitiesBladimir Iles ChavesNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its SettingDocument10 pagesThe Problem and Its Settingczarina_roqueNo ratings yet

- MSC Child and Adolescent Psychology Psyc 1107 Advanced Research Methods For Child Development M01Document10 pagesMSC Child and Adolescent Psychology Psyc 1107 Advanced Research Methods For Child Development M01macapashaNo ratings yet

- 10th Research ForumDocument14 pages10th Research ForumvinaNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of Adult Sex EducationDocument50 pagesAn Assessment of Adult Sex Educationapi-550131693No ratings yet

- Phenomenolgical Research AbstractsDocument64 pagesPhenomenolgical Research AbstractsMohammad Rafiuddin100% (1)

- Adolescent Girls' Knowledge and Attitude About Mental Health Issues: A QuestionnaireDocument8 pagesAdolescent Girls' Knowledge and Attitude About Mental Health Issues: A QuestionnaireamritaNo ratings yet

- FALLSEM2023-24 HUM1021 TH VL2023240108380 2023-10-10 Reference-Material-IDocument10 pagesFALLSEM2023-24 HUM1021 TH VL2023240108380 2023-10-10 Reference-Material-Ibefimo7388No ratings yet

- Health 8 WK 2 Final VersionDocument6 pagesHealth 8 WK 2 Final VersionMarlon Joseph D. ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Parent-Assisted Social Skills Training To Improve Friendships in Teens With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument12 pagesParent-Assisted Social Skills Training To Improve Friendships in Teens With Autism Spectrum DisordersroosendyannisaNo ratings yet

- Application of The Functional, Expressive and Aesthetic Consumer Needs Model Assessing The Clothing Needs of Adolescent Girls With DisabilitiesDocument10 pagesApplication of The Functional, Expressive and Aesthetic Consumer Needs Model Assessing The Clothing Needs of Adolescent Girls With DisabilitiesAsish DasNo ratings yet

- The Contribution of ADHD and ADocument6 pagesThe Contribution of ADHD and AAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Transgender Experiences of Occupation and The Environment A Scoping ReviewDocument16 pagesTransgender Experiences of Occupation and The Environment A Scoping ReviewAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Why Sexuality Education For People With Developmental Disabilities Is So Important - NESCADocument4 pagesWhy Sexuality Education For People With Developmental Disabilities Is So Important - NESCAAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Why Has So Little Progress BeeDocument6 pagesWhy Has So Little Progress BeeAsish DasNo ratings yet

- AdolescenceDocument6 pagesAdolescenceAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Youths With Disabilities Need Education, Guidance On Sexual Health: AAPDocument3 pagesYouths With Disabilities Need Education, Guidance On Sexual Health: AAPAsish DasNo ratings yet

- 12 AbstractDocument2 pages12 AbstractAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Acharya 2014 Preparing For Motherhood A Role ForDocument3 pagesAcharya 2014 Preparing For Motherhood A Role ForAsish DasNo ratings yet

- The Role of Clothing in Participation of Persons With A Physical Disability A Scoping Review ProtocolDocument6 pagesThe Role of Clothing in Participation of Persons With A Physical Disability A Scoping Review ProtocolAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Fredriksen Goldsen 2012 Disability Among Lesbian Gay and BiDocument6 pagesFredriksen Goldsen 2012 Disability Among Lesbian Gay and BiAsish DasNo ratings yet

- Chapter One 1.1 Background of The StudyDocument25 pagesChapter One 1.1 Background of The StudySHAKIRAT ADUUNINo ratings yet

- Unit 4f Teaching Grammar 3 Using Communicative ActivitiesDocument7 pagesUnit 4f Teaching Grammar 3 Using Communicative ActivitiesKhalil MesrarNo ratings yet

- Wvu Unit Plan1-6Document5 pagesWvu Unit Plan1-6api-267333082No ratings yet

- Qualities of A Teacher in The New NormalDocument7 pagesQualities of A Teacher in The New NormalObet BerotNo ratings yet

- Christopher Manning Lecture 5: Language Models and Recurrent Neural Networks (Oh, and Finish Neural Dependency Parsing J)Document66 pagesChristopher Manning Lecture 5: Language Models and Recurrent Neural Networks (Oh, and Finish Neural Dependency Parsing J)Muhammad Arshad AwanNo ratings yet

- National Orientation: Guidelines On The Basic Education Enrollment For SCHOOL YEAR 2020-2021Document46 pagesNational Orientation: Guidelines On The Basic Education Enrollment For SCHOOL YEAR 2020-2021RobieDeLeonNo ratings yet

- Lantite ResultsDocument2 pagesLantite Resultsapi-527349815No ratings yet

- PPST Module 4-Emerging Assessment Strategies For Improved Teaching and Learning GROUP 18Document13 pagesPPST Module 4-Emerging Assessment Strategies For Improved Teaching and Learning GROUP 18Regine LetchejanNo ratings yet

- ACEWM Call For Application 2019 2020Document3 pagesACEWM Call For Application 2019 2020NgendahayoNo ratings yet

- Ten Minute Leadership LessonDocument40 pagesTen Minute Leadership LessonJoy SalvadorNo ratings yet

- G11 Q1 RequirementsDocument2 pagesG11 Q1 RequirementsRam KuizonNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1. State The Legal Basis of The Teaching of Physical Education (PE)Document2 pagesAssessment 1. State The Legal Basis of The Teaching of Physical Education (PE)Mar Jory del Carmen BaldoveNo ratings yet

- 14. Using Campinha-Bacote’s framework to examine cultural competence from an interdisciplinary international service learning program. Elizabeth D. Wall-Bassett, Western Carolina University, United States; Archana V. Hegde, Katelyn Craft & Amber L. Oberlin, East Carolina University, United States; pp. 274-283Document10 pages14. Using Campinha-Bacote’s framework to examine cultural competence from an interdisciplinary international service learning program. Elizabeth D. Wall-Bassett, Western Carolina University, United States; Archana V. Hegde, Katelyn Craft & Amber L. Oberlin, East Carolina University, United States; pp. 274-283STAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Sinopsis Buku THE PRACTICE OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING SPLKPM 2023Document2 pagesSinopsis Buku THE PRACTICE OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING SPLKPM 2023mokzzzNo ratings yet

- Assessment and EvaluationDocument11 pagesAssessment and EvaluationAryahebwa JosephineNo ratings yet

- Sweet Demonstration TeachingDocument2 pagesSweet Demonstration TeachingMary GraceNo ratings yet

- Captioned Media in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching - Subtitles For The Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing As Tools For LanguaDocument277 pagesCaptioned Media in Foreign Language Learning and Teaching - Subtitles For The Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing As Tools For LanguahighpalmtreeNo ratings yet

- Learning: St. Mary's College of Tagum, IncDocument4 pagesLearning: St. Mary's College of Tagum, IncJunly AberillaNo ratings yet

- 3 RRLDocument5 pages3 RRLChristian VillaNo ratings yet

- Homework Sheets Ks3 EnglishDocument5 pagesHomework Sheets Ks3 Englishh4aa4bv8100% (1)

- Effects of Using Casio FX991 ES PLUS On Achievement and Anxiety Level in MathematicsDocument8 pagesEffects of Using Casio FX991 ES PLUS On Achievement and Anxiety Level in MathematicsPeter QuintosNo ratings yet