Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Primary Evaluation and Acute Management of Vertigo.17

Uploaded by

nawal asmadiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Primary Evaluation and Acute Management of Vertigo.17

Uploaded by

nawal asmadiCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

Primary Evaluation and Acute Management of Vertigo

Sisha Liz Abraham

Department of Surgical Oncology, Cochin Cancer Research Centre, Kochi, Kerala, India

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/cmii by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AW

Abstract

nYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC1y0abggQZXdgGj2MwlZLeI= on 01/18/2024

Vertigo, an illusory movement, arises mostly because of lesions in the peripheral vestibular system (e.g., damage or dysfunction of the labyrinth and

vestibular nerve) and occasionally that of central vestibular structures. Patients give various descriptions of vertigo: a head‑spinning feeling, swaying,

tilting, or an imbalance in walking depending on the location of the lesion. Acute vertigo remains a diagnostic challenge for the physicians due to the

wide array of differential diagnosis. It is important to distinguish the central causes of vertigo from its peripheral causes. Benign paroxysmal positional

vertigo (BPPV) is one of the most common causes of peripheral vertigo, most commonly attributed to calcium debris within the posterior semicircular

canal, known as canalithiasis. Prompt diagnosis by positional testing (e.g., Dix–Hallpike), performing a bedside repositioning maneuver (e.g., Epley)

and administering symptomatic therapy helps in providing the quick relief to the highly distressing symptom of vertigo due to BPPV.

Keywords: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Epley maneuver, peripheral vertigo, vertigo

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sisha Liz Abraham, Department of Surgical Oncology, Cochin Cancer Research Centre, Kochi, Kerala, India.

E‑Mail: sisha.liz@gmail.com

Introduction

Vertigo is a symptom of illusory movement (feels as if the person or the objects around them are moving when they are not). It

arises because of abnormalities in the peripheral vestibular system (e.g., damage to/dysfunction of the components of labyrinth

and vestibular nerve) or from the lesions of the central vestibular structures in the brainstem.[1‑3] It is associated with significant

disability and can be prolonged or intermittent in nature. Vertigo, as a symptom, poses a significant challenge to emergency care

physicians as they have to consider a wide array of differential diagnosis in a short span of time and localize the lesion [Table 1].

Hence, a prompt and timely diagnosis is essential to initiate any early intervention that is required.

Vertigo is a symptom and not a diagnosis. Patients varyingly describe it as a head‑spinning feeling, swaying, tilting, or an

imbalance in walking depending on the exact site of abnormality.[4‑6] The most common sensation is a rotatory sensation, though

it is not always the case. Vertigo can occur as a single or recurrent episode and may last seconds, hours, or days. Acute vertigo

may be associated with nausea and vomiting, which may be significant enough to cause dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

A summary of the clinical features of common forms of acute vertigo is shown in Table 2.

The evaluation of a patient with vertigo is shown in Figure 1.

Evaluation: History

A history of the symptoms plays a key role in distinguishing vertigo from the other differentials and in localizing the lesion.

Try to obtain an unprompted description of the patient’s “dizziness” or “giddiness.” Cardiovascular causes usually lead to

Date of Submission: 08‑Feb‑2020 Date of Review: 09-Feb-2020

Date of Acceptance: 04-Mar-2020 Date of Web Publication: 10-Jul-2020

Access this article online This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative

Quick Response Code: Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to

Website: remix, tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as appropriate credit

www.cmijournal.org is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

DOI:

10.4103/cmi.cmi_11_20 How to cite this article: Abraham SL. Primary evaluation and acute

management of vertigo. Curr Med Issues 2020;18:217-21.

© 2020 Current Medical Issues | Published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow 217

Abraham: Primary management of vertigo and BPPV

presyncope/syncope and neurological causes are accompanied evaluation in emergency care. A good history should include

by disequilibrium. Hence, both should be ruled out during the the following:

• Time course of events:

• Recurrent vertigo of short duration with positional

Table 1: Common causes of central and peripheral vertigo

variation suggests benign paroxysmal positional

Peripheral causes Central causes vertigo (BPPV) whereas that of long duration

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo Vestibular migraine suggests Meniere’s disease[7,8]

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/cmii by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AW

Vestibular neuritis Brainstem ischemia • A single episode of vertigo lasting many hours may

Meniere’s disease Cerebellar infarction point to migraine or transient ischemic attack of the

and hemorrhage brain stem[9]

Herpes zoster oticus Head trauma • Labyrinthitis and vestibular neuronitis are typically

nYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC1y0abggQZXdgGj2MwlZLeI= on 01/18/2024

Labyrinthine concussion associated with the vertigo of prolonged duration over

Otitis media days.[10,11]

Table 2: Clinical features of common causes of vertigo[3]

Time course Suggestive clinical Associated Auditory symptoms Other diagnostic

setting neurologic symptoms features

Benign paroxysmal Recurrent, brief(s) Predictable head None None Dix‑Hallpike

positional vertigo movement/positions maneuver is

precipitate symptoms diagnostic

Vestibular neuritis Single episode, acute History of or Falls toward the side Usually none Head thrust test

onset, lasts days accompanying viral of the lesion, no usually abnormal

syndrome brainstem signs

Meniere’s disease Recurrent episodes, Spontaneous onset None May be preceded by Audiometry shows

last min‑several hours ear pain, U/L hearing U/L sensorineural

loss, tinnitus hearing loss

Vestibular migraine Recurrent episodes, History of migraine Migraine headache Usually none Between episodes,

(peripheral/central last several minutes and/or other tests are usually

nystagmus) to hours migrainous symptoms normal

Abhilash[3]

Figure 1: Evaluation of a patient with vertigo.

218 Current Medical Issues ¦ Volume 18 ¦ Issue 3 ¦ July‑September 2020

Abraham: Primary management of vertigo and BPPV

• Aggravating and relieving factors: All types of vertigo Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

become symptomatically worse with the head movement.

BPPV is one of the most common causes of vertigo presenting

Most patients prefer to keep their head still in fear

in the emergency department. It is a mechanical disorder of

of worsening of symptoms. Vertigo aggravated by or

the inner ear and is commonly attributed to free‑floating debris

provoked with specific head movements or postures is

within the semicircular canal (posterior being the most common),

typical of BPPV. History of head trauma should always

known as canalithiasis.[16‑18] This debris likely represents loose

be sought for the likely possibility of whiplash or that

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/cmii by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AW

otoconia (calcium carbonate crystals) within the auricular sac.

of perilymphatic fistula.[12] History of vertigo and a

These are normal structures that are displaced from the utricle.

recent viral infection suggest the possibility of vestibular

neuronitis caused by the inflammation of the eighth cranial There are three variants:

nerve[11] • Posterior canal (prototype/classical) – the most common

nYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC1y0abggQZXdgGj2MwlZLeI= on 01/18/2024

• Associated symptoms: The features of the brain stem • Horizontal canal (lateral canal) – the second‑most

involvement such as diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, common

weakness, or numbness suggest vertigo due to a • Anterior canal (superior canal).

vertebrobasilar stroke. Peripheral vertigo associated with

the symptoms such as deafness and tinnitus may point to Posterior Canal Benign Paroxysmal Positional

Meniere’s disease. Headache and photophobia are usually

associated with migrainous vertigo[9] Vertigo (Proto‑Type/Classical)

• Past medical history: A significant past medical history Recurrent episodes of vertigo lasting 1 min or less. Although

includes a history of migraine, risk factors for a individual episodes are brief, these typically recur periodically

cerebrovascular accident (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, for weeks to months without therapy. Episodes are provoked by

smoking, etc.), other neurological disorders, status the specific types of head movements, such as looking up while

of vision, psychiatric issues, and past history of head standing or sitting, lying down or getting up from bed, and

trauma. Certain medications (aminoglycosides, cisplatin, rolling over in bed. The spells may wax and wane over time.

and phenytoin) can cause vertigo, and drug history is Vertigo may be associated with nausea and at times vomiting.

absolutely essential.[13]

Examination

Nystagmus is optimally provoked by the Dix–Hallpike or

Evaluation: Examination Nylen–Barany maneuver (sensitivity 50%–88%).[14] Nystagmus

It is important to perform a complete otologic and neurologic is an involuntary movement of the eye characterized by a

examination in patients presenting with vertigo. smooth pursuit eye movement followed by a rapid saccade in

• Nystagmus: It is a rhythmic oscillation of the eyes. The the opposite direction of the smooth pursuit eye movement.

patient with the acute onset of vertigo tends to have Dix–Hallpike maneuver is helpful in diagnosing the classical

nystagmus when the gaze is not fixed. In peripheral posterior canal BPPV. The test itself may provoke severe

vertigo, the fast phase is usually away from the affected vertigo. Premedication with betahistine or dimenhydrinate IM

side. Peripheral vertigo is characterized by horizontal or or IV may make the test more tolerable and will not diminish

torsional or mixed nystagmus, but never vertical. Central the nystagmus.

vertigo may have any trajectory, but vertical nystagmus Dix‑Hallpike maneuver

strongly suggests a central origin of vertigo • Instruct the patient to keep their eyes open all the time

• Other neurological signs: A detailed central nervous and look at the examiners face

system exami nation look i ng for cranial ner ve • With the patient sitting, extend the neck and turn to one

abnormalities, cerebellar signs, motor or sensory side

changes, or abnormal reflexes, which would indicate a • Place the patient supine rapidly, so that the head hangs

central cause for vertigo over the edge of the bed

• Tests of hearing: Bedside tests of hearing (Weber and • Keep the patient in this position until 30 s have passed if

Rinne tests) and an otoscopic examination of the tympanic no nystagmus occurs

membrane for evidence acute or chronic otitis media. It • The patient should also be queried about the presence of

should be performed to distinguish the etiology of vertigo subjective vertigo

• Dix‑Hallpike maneuver: The most important cause of • Return the patient to upright position, observe for another

vertigo that present as an acute emergency is BPPV. This 30 s for nystagmus, and then repeat the maneuver with

maneuver is helpful in diagnosing the classical posterior the head turned to the other side.

canal BPPV. It should not be performed in patients

with a carotid bruit or risk factors for vertebrobasilar Diagnostic criteria employing the Dix–Hallpike maneuver

insufficiency due to a theoretical risk of precipitating a for posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

cerebrovascular accident.[14,15] The test is diagnostic for • Nystagmus and vertigo usually appear with a latency of

BPPV if positive, but does not rule it out if negative. a few seconds and last <60 s

Current Medical Issues ¦ Volume 18 ¦ Issue 3 ¦ July‑September 2020 219

Abraham: Primary management of vertigo and BPPV

• It has a typical trajectory, beating upward and torsionally,

Table 3: Particle repositioning maneuver (Epley maneuver)

with the upper poles of the eyes beating toward the ground

with a crescendo‑decrescendo pattern Epley maneuver for the right side BPPV

• After it stops and the patient sits up, the nystagmus may Step 1: The patient seated with head erect and facing forward

recur but in the opposite direction Step 2: The head is turned toward 45° to the right, and the patient is

• The patient should then have the maneuver repeated to the moved rapidly into a supine position with head extending just beyond

same side, with each repetition, the intensity and duration examining table (45° to horizontal), right ear down

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/cmii by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AW

of nystagmus will diminish.(nystagmus fatigability) Step 3: Examiner moves to head end of the table

• The side showing the positive test is the side of the lesion. Step 4: Head is quickly rotated to the left side. Right ear upward

(90° to the left). This position is held for 30 s

The clinical practice guideline published by the American

Step 5: The patient rolls into the left side while the examiner rapidly rotates

Academy of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery

nYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC1y0abggQZXdgGj2MwlZLeI= on 01/18/2024

head until the nose is angled toward the floor. This position is held for 30 s

does not include nystagmus fatigability as a diagnostic

Step 6: The patient is rapidly lifted into the sitting position

criterion.[19] If the patient’s history is compatible with BPPV,

but the Dix–Hallpike test exhibits no nystagmus or horizontal

nystagmus, and the clinician should perform a supine roll test

to assess for lateral semicircular canal BPPV.

Supine head roll test (Pagnini‑Lempert or Pagnini‑McClure

Roll test) for lateral canal benign paroxysmal positional

vertigo

• The patient is made to lie supine with the head in the

neutral position, followed by quickly rotating the head

90° to one side

• The patient’s eyes are observed for nystagmus

• Once the nystagmus subsides or if no nystagmus is

elicited, the head is then brought back to the straight face

up supine position

• If any additional nystagmus is elicited, it is allowed

to settle and the head is then quickly turned 90° to the

opposite side, and the eyes are once again observed for

Figure 2: Epley maneuver. The patient is instructed to lie supine or to left

nystagmus.

with the head elevated after the procedure and be preferably on bed rest

Lateral semicircular canal BPPV may occur following the after the procedure for 48 h. The entire sequence is repeated later for

performance of the canalith repositioning procedure for residual symptoms. BPPV: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

an initial diagnosis of posterior semicircular canal BPPV

(canal conversion). Hence, clinicians should be aware of lateral Commonly used medications for vertigo

semicircular canal BPPV and its diagnosis.[20] • Tablet cinnarizine 25 mg three times a day OR

• Tablet betahistine 16 mg three times a day OR

Acute Management of Benign Paroxysmal • Tablet prochlorperazine 10 mg three times a day OR

• Tablet flunarizine 10 mg three times a day OR

Positional Vertigo • Tablet promethazine 25 mg twice a day OR

The particle repositioning maneuver (Epley maneuver more • Syrup diphenhydramine 10–20 ml three times a day.

commonly practiced than Semont maneuver) should be

performed for all patients with confirmed posterior canal BPPV. These drugs are quite effective for acute symptomatic relief

The Epley maneuver for a right side BPPV is shown in Table 3 of vertigo. Antihistamines are usually used as the first choice

and Figure 2. This procedure alone provides significant symptom for most patients, with sedation being a common side effect.

relief in many patients.[21,22] Lempert 360 roll maneuver or The phenothiazine antiemetics such as prochlorperazine and

Gufoni maneuver is performed for lateral canal BPPV. promethazine are more sedating and hence are reserved for

patients with severe vomiting. Benzodiazepines too are quite

Oral medications may then be added for additional symptomatic sedative and are reserved for patients with severe symptoms.

management. The following classes of drugs are effective in The drug of choice in pregnancy is meclizine.[23]

suppressing the vestibular system.

• Antihistamines: diphenhydramine, dimenhydrinate,

cinnarizine, and meclizine Conclusion

• Antiemetics: prochlorperazine, promethazine, ondansetron, Acute vertigo remains a diagnostic challenge for emergency

and metoclopramide physicians due to the wide array of differential diagnosis.

• Benzodiazepines: diazepam, lorazepam, and alprazolam. It may be categorized as central or peripheral and making

220 Current Medical Issues ¦ Volume 18 ¦ Issue 3 ¦ July‑September 2020

Abraham: Primary management of vertigo and BPPV

the distinction between the two is the most important part 2001;56:436‑41.

of evaluation. A thorough history is important to distinguish 10. Schessel DA, Minor LB, Nedzelski J. Meniere’s disease and other

peripheral vestibular disorders. In: Gaertner RS, Murphy MB,

vertigo from other forms of giddiness or lightheadedness. editors. Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 4th ed.,

Laboratory testing and radiography are not routinely indicated Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004. p. 3231‑2.

in the workup of patients with vertigo when no other neurologic 11. Baloh RW. Clinical practice. Vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med

abnormalities are present. Prompt diagnosis, performing a 2003;348:1027‑32.

12. Black FO, Pesznecker S, Norton T, Fowler L, Lilly DJ, Shupert C, et al.

bedside canalith repositioning maneuver, and administering

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/cmii by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AW

Surgical management of perilymphatic fistulas: A Portland experience.

symptomatic therapy help in quick relief in BPPV which Am J Otol 1992;13:254‑62.

happens to be the most common cause of vertigo. 13. Cianfrone G, Pentangelo D, Cianfrone F, Mazzei F, Turchetta R,

Orlando MP, et al. Pharmacological drugs inducing ototoxicity,

Financial support and sponsorship vestibular symptoms and tinnitus: A reasoned and updated guide. Eur

Nil. Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2011;15:601‑36.

nYQp/IlQrHD3i3D0OdRyi7TvSFl4Cf3VC1y0abggQZXdgGj2MwlZLeI= on 01/18/2024

14. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. The pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis

Conflicts of interest of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Ann Otol Rhinol

There are no conflicts of interest. Laryngol 1952;61:987‑1016.

15. Hilton MP, Pinder DK. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre

for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

References 2014;(12):CD003162.

16. Brandt T, Steddin S. Current view of the mechanism of benign

1. Neuhauser HK. Epidemiology of vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol

2007;20:40‑6. paroxysmal positioning vertigo: Cupulolithiasis or canalolithiasis? J

2. Norrving B, Magnusson M, Holtås S. Isolated acute vertigo in the Vestib Res 1993;3:373‑82.

elderly; vestibular or vascular disease? Acta Neurol Scand 1995;91:43‑8. 17. Vannucchi P, Giannoni B, Pagnini P. Treatment of horizontal semicircular

3. Abhilash KP. Emergency Medicine: Best Practices at CMC. 2nd ed., Ch. canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res 1997;7:1‑6.

87, 282. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers’ Medical Publishers; 2019. 18. Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign

4. Newman‑Toker DE, Cannon LM, Stofferahn ME, Rothman RE, paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ 2003;169:681‑93.

Hsieh YH, Zee DS. Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom 19. Bhattacharyya N, Gubbels SP, Schwartz SR, Edlow JA, El‑Kashlan H,

quality: A cross‑sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Fife T, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional

Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:1329‑40. Vertigo (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;156:S1‑S47.

5. Stanton VA, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA Jr., Edlow JA, Lovett PB, 20. White JA, Coale KD, Catalano PJ, Oas JG. Diagnosis and management

Goldstein JN, et al. Overreliance on symptom quality in diagnosing of lateral semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

dizziness: Results of a multicenter survey of emergency physicians. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;133:278‑84.

Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:1319‑28. 21. Helminski JO, Zee DS, Janssen I, Hain TC. Effectiveness of particle

6. Nedzelski JM, Barber HO, McIlmoyl L. Diagnoses in a dizziness unit. repositioning maneuvers in the treatment of benign paroxysmal

J Otolaryngol 1986;15:101‑4. positional vertigo: A systematic review. Phys Ther 2010;90:663‑78.

7. Karlberg M, Hall K, Quickert N, Hinson J, Halmagyi GM. What 22. Strupp M, Cnyrim C, Brandt T. Vertigo and dizziness: Treatment

inner ear diseases cause benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Acta of benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo, vestibular neuritis

Otolaryngol 2000;120:380‑5. and Menère’s disease. In: Candelise L, editor. Evidence‑Based

8. Epley JM. New dimensions of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology‑Management of Neurological Disorders. Oxford: Blackwell

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (1979) 1980;88:599‑605. Publishing; 2007. p. 59‑69.

9. Neuhauser H, Leopold M, von Brevern M, Arnold G, Lempert T. The 23. Leathem AM. Safety and efficacy of antiemetics used to treat nausea and

interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo. Neurology vomiting in pregnancy. Clin Pharm 1986;5:660‑8.

Current Medical Issues ¦ Volume 18 ¦ Issue 3 ¦ July‑September 2020 221

You might also like

- Vertigo, A Simple Guide to The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandVertigo, A Simple Guide to The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- VertDocument9 pagesVertIka PurnamawatiNo ratings yet

- Vestibular DisorderDocument6 pagesVestibular DisorderEcaterina ChiriacNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Interventions in Vertigo ManagementDocument9 pagesTherapeutic Interventions in Vertigo ManagementtamiNo ratings yet

- Healing Is Voltage - The Handbook (2014) PDFDocument470 pagesHealing Is Voltage - The Handbook (2014) PDFShaun Oneill100% (3)

- Vestibular Function Evaluation & DiagnosisDocument98 pagesVestibular Function Evaluation & DiagnosisЭ.ТөгөлдөрNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Patient With DizzinessDocument5 pagesApproach To The Patient With DizzinessHuda HamoudaNo ratings yet

- Oral Tumor / Cancer: Wirsma Arif Harahap Head Neck and Breast Oncology Consultant Andalas Medical School PadangDocument55 pagesOral Tumor / Cancer: Wirsma Arif Harahap Head Neck and Breast Oncology Consultant Andalas Medical School Padangnawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- BPPV PDFDocument10 pagesBPPV PDFNamun Sibora BoraNo ratings yet

- Krok 2 - 2023 (14 March) (General Medicine) - 1Document19 pagesKrok 2 - 2023 (14 March) (General Medicine) - 1berdaderagaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Patient With Vertigo - UpToDate PDFDocument29 pagesEvaluation of The Patient With Vertigo - UpToDate PDFDanna GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Vestibular DisordersDocument8 pagesVestibular DisordersHilwy Al-haninNo ratings yet

- Dizziness: Classification and PathophysiologyDocument16 pagesDizziness: Classification and Pathophysiologyrapannika100% (2)

- Evaluation of The Patient With Vertigo - UpToDateDocument34 pagesEvaluation of The Patient With Vertigo - UpToDateadngdNo ratings yet

- Avaliação Do Pcte Com Vertigem UptodateDocument31 pagesAvaliação Do Pcte Com Vertigem UptodatePaula OhanaNo ratings yet

- "Approach To The Patient With Vertigo" "Evaluation of Syncope in Adults"Document8 pages"Approach To The Patient With Vertigo" "Evaluation of Syncope in Adults"Fila DelviaNo ratings yet

- The Bedside Assessment of VertigoDocument5 pagesThe Bedside Assessment of VertigoManuek GarciaNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument13 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptNia WillyNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The Vestibular System: History and Physical ExaminationDocument11 pagesAssessment of The Vestibular System: History and Physical ExaminationmykedindealNo ratings yet

- R 1095 PDFDocument7 pagesR 1095 PDFAndro SinagaNo ratings yet

- Positional VertigoDocument12 pagesPositional VertigoCribea AdmNo ratings yet

- Sumber 3Document3 pagesSumber 3Ali Laksana SuryaNo ratings yet

- Vertigo NoteDocument4 pagesVertigo Notemarmagia thomasNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of The Dizzy PatientDocument9 pagesEvaluation and Management of The Dizzy Patientsara mohamedNo ratings yet

- Vertigo In-ServiceDocument8 pagesVertigo In-Serviceapi-612663095No ratings yet

- Approach To The Patient With Dizziness - UpToDateDocument18 pagesApproach To The Patient With Dizziness - UpToDateImad RifayNo ratings yet

- Vestibular RehabDocument6 pagesVestibular RehabssgamNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of The Dizzy Patient: L M LuxonDocument8 pagesEvaluation and Management of The Dizzy Patient: L M LuxonCarolina Sepulveda RojasNo ratings yet

- Vertigo: Part 1 - Assessment in General PracticeDocument5 pagesVertigo: Part 1 - Assessment in General PracticeRajbarinder Singh RandhawaNo ratings yet

- ProprioceptiveDocument15 pagesProprioceptivebae addictNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing the cause of vertigo: a practical approach: Alex TH Lee 李定漢Document6 pagesDiagnosing the cause of vertigo: a practical approach: Alex TH Lee 李定漢Gh. AhmedNo ratings yet

- Articol OrlDocument6 pagesArticol OrlSabina BădilăNo ratings yet

- Neurology Vertigo PathwayDocument9 pagesNeurology Vertigo PathwayMuh Abdul wahidNo ratings yet

- Gadingzhr, ARTIKEL 7Document6 pagesGadingzhr, ARTIKEL 7NqbilNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Interventions in Vertigo Management: Review ArticleDocument12 pagesTherapeutic Interventions in Vertigo Management: Review ArticleAdityaNo ratings yet

- Central vs. Peripheral VertigoDocument3 pagesCentral vs. Peripheral VertigoDino AdijayaNo ratings yet

- Welgamp OLADocument14 pagesWelgamp OLASofiaNo ratings yet

- Vertigo: Ika Marlia Bagian Neurologi RSUDZA/FK UNSYIAH Banda AcehDocument33 pagesVertigo: Ika Marlia Bagian Neurologi RSUDZA/FK UNSYIAH Banda AcehChesy oety otawaNo ratings yet

- Presbyastasis A Multifactorial Cause of Balance Problems in The ElderlyDocument5 pagesPresbyastasis A Multifactorial Cause of Balance Problems in The Elderlydarmayanti ibnuNo ratings yet

- 6 - Vertebral Joint Mobilisation - Cervical Spine VDocument28 pages6 - Vertebral Joint Mobilisation - Cervical Spine VWalaa MohamedNo ratings yet

- Journal of Surgery Forecast: Vertigo: A Spectrum of CasesDocument4 pagesJournal of Surgery Forecast: Vertigo: A Spectrum of CasesKalyani IngoleNo ratings yet

- Vestibularneuritis: John C. Goddard,, Jose N. FayadDocument5 pagesVestibularneuritis: John C. Goddard,, Jose N. Fayaddarmayanti ibnuNo ratings yet

- Pharmacologic Treatment of Vestibular Disorders: Surgical Treatments - in Less FrequentDocument8 pagesPharmacologic Treatment of Vestibular Disorders: Surgical Treatments - in Less FrequentRay MaudyNo ratings yet

- Zee Bedside ExamDocument20 pagesZee Bedside Examhikmat sheraniNo ratings yet

- APA VBI GuidelinesDocument14 pagesAPA VBI Guidelinesbruno santosNo ratings yet

- Biofeedback For Vertigo 2ndry To Cervical LesionDocument7 pagesBiofeedback For Vertigo 2ndry To Cervical LesionBassam EsmailNo ratings yet

- NCM116 Finals Assessment of The Nervous SystemDocument9 pagesNCM116 Finals Assessment of The Nervous SystemRachelle DelantarNo ratings yet

- Podział Diagnostyka PDFDocument9 pagesPodział Diagnostyka PDFMagda KupczyńskaNo ratings yet

- Vertigo and ImbalanceDocument19 pagesVertigo and ImbalanceDiena HarisahNo ratings yet

- Chimirri Et Al 2013 Vertigo Dizziness As A Drugs Adverse ReactionDocument6 pagesChimirri Et Al 2013 Vertigo Dizziness As A Drugs Adverse ReactionNASTITI PUTRI NARISWARINo ratings yet

- Visual Vertigo, Motion Sickness, and Disorientation in VehiclesDocument14 pagesVisual Vertigo, Motion Sickness, and Disorientation in VehiclesOtorrino Rubén González Plástica Nasal-VértigoNo ratings yet

- V - Stibular Rehabilitation - Critical Decision AnalysisDocument12 pagesV - Stibular Rehabilitation - Critical Decision AnalysisKapil LakhwaraNo ratings yet

- 171120se-Bvsspa Sod 14008603Document5 pages171120se-Bvsspa Sod 1400860306trahosNo ratings yet

- Clinthera CaseDocument7 pagesClinthera CaseRishi Du AgbugayNo ratings yet

- Vestibular NeuronitisDocument8 pagesVestibular NeuronitisFatimah AssagafNo ratings yet

- Ataxia: Dr. Vipinnath E.N. (PT)Document18 pagesAtaxia: Dr. Vipinnath E.N. (PT)AKHILNo ratings yet

- PEMERIKSAAN PENUNJANG VertigoDocument4 pagesPEMERIKSAAN PENUNJANG Vertigotutut saNo ratings yet

- Vestibular Migraine An UpdateDocument15 pagesVestibular Migraine An UpdateSerdar MeteNo ratings yet

- Approaching Acute Vertigo With Diplopia - A Rare Skew Deviation in Vestibular NeuritisDocument7 pagesApproaching Acute Vertigo With Diplopia - A Rare Skew Deviation in Vestibular NeuritisRudolfGerNo ratings yet

- Vestibular NeuronitisDocument17 pagesVestibular Neuronitisimran qaziNo ratings yet

- Cervicogenicdizziness 210215 120659Document13 pagesCervicogenicdizziness 210215 120659doctorkenabreuNo ratings yet

- History and Physical Examination For Shoulder InstabilityDocument6 pagesHistory and Physical Examination For Shoulder InstabilitydrjorgewtorresNo ratings yet

- Virus Replication: John Goulding, Imperial College London, UKDocument1 pageVirus Replication: John Goulding, Imperial College London, UKnawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Praktikum Patologi Anatomi: Blok 2.1 Minggu 1 Jejas Sel & InflamasiDocument25 pagesPraktikum Patologi Anatomi: Blok 2.1 Minggu 1 Jejas Sel & Inflamasinawal asmadiNo ratings yet

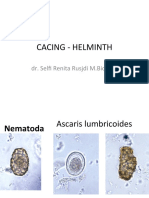

- Helminth - PictureDocument17 pagesHelminth - Picturenawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis: by Avit SuchitraDocument33 pagesAcute Appendicitis: by Avit Suchitranawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- 2.4.4.3D Reye's Syndrome - Dr. SaptinoDocument48 pages2.4.4.3D Reye's Syndrome - Dr. Saptinonawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Abnormalities in The Digestive SystemDocument2 pagesAbnormalities in The Digestive Systemnawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Tumor Saluran Cerna AtasDocument85 pagesTumor Saluran Cerna Atasnawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Healthy LifestyleDocument3 pagesHealthy Lifestylenawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Diabtes Melitus Pada Anak (DM Tipe 1)Document51 pagesDiabtes Melitus Pada Anak (DM Tipe 1)nawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Calculation of Metabolic RateDocument6 pagesCalculation of Metabolic Ratenawal asmadiNo ratings yet

- Unit Learning Plan Health 9 Quarter 3Document4 pagesUnit Learning Plan Health 9 Quarter 3ELLA VANI MARIE HINOLANNo ratings yet

- The Spine FrequenciesDocument2 pagesThe Spine Frequencieschris adiNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Bone DiseaseDocument52 pagesPresentation On Bone DiseaseNoor-E-Khadiza ShamaNo ratings yet

- Manfaat Rendaman Air Hangat Dan Garam Dalam Menurunkan Derajat Edema Kaki Ibu Hamil Trimester IiiDocument6 pagesManfaat Rendaman Air Hangat Dan Garam Dalam Menurunkan Derajat Edema Kaki Ibu Hamil Trimester IiiShinta BalikpapanNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Hepatitis B VirusDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Hepatitis B Virusafmzeracmdvbfe100% (1)

- Efek Zumba PDF 1Document1 pageEfek Zumba PDF 1Nury HerdiantiNo ratings yet

- Icmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (These Fields To Be Filled For All Patients Including Foreigners)Document2 pagesIcmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (These Fields To Be Filled For All Patients Including Foreigners)nitish mahatoNo ratings yet

- Mental Status Examination DefinitionsDocument8 pagesMental Status Examination DefinitionsCelebrity HubNo ratings yet

- The Misuse of Mobile PhoneDocument3 pagesThe Misuse of Mobile Phoneyisethe melisa erira menesesNo ratings yet

- Biotechnology and Its ApplicationsDocument27 pagesBiotechnology and Its ApplicationsKA AngappanNo ratings yet

- The Different Perspectives of DisasterDocument3 pagesThe Different Perspectives of DisasterJuliane Rebecca PitlongayNo ratings yet

- Meningocele ReconDocument15 pagesMeningocele ReconI Wayan ArimbawaNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Investigatory Project: Study of Oxalate Ion Content in Guava FruitDocument18 pagesChemistry Investigatory Project: Study of Oxalate Ion Content in Guava Fruityour saviorNo ratings yet

- Stained Febrile AntigensDocument1 pageStained Febrile AntigensmsaidsaidyoussefNo ratings yet

- Extraction of Catechin From Testa and LeavesDocument24 pagesExtraction of Catechin From Testa and LeavesĐức Kiều TríNo ratings yet

- Clinician's Manual S8 AutoSet IIDocument70 pagesClinician's Manual S8 AutoSet IIsles22No ratings yet

- Editorial: Education in The New Normal: Basey II District's Learning Amidst COVID-19Document1 pageEditorial: Education in The New Normal: Basey II District's Learning Amidst COVID-19EricsonCaburnidaSabanganNo ratings yet

- Murine TyphusDocument3 pagesMurine TyphusKeesha Mae Urgelles TimogNo ratings yet

- Osg Catalogue March 2021Document72 pagesOsg Catalogue March 2021Ritvik KhuranaNo ratings yet

- Phylum PlatyhelminthesDocument6 pagesPhylum PlatyhelminthesosaydNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Studies of Medicinal Plant Citrullus Colocynthis: A ReviewDocument9 pagesPharmacological Studies of Medicinal Plant Citrullus Colocynthis: A ReviewVinayNo ratings yet

- Hippo EM Board Review - Renal & GU Written SummaryDocument15 pagesHippo EM Board Review - Renal & GU Written Summarykaylawilliam01No ratings yet

- Form 5 Cambridge VocabularyDocument7 pagesForm 5 Cambridge Vocabulary41 SHI YING WONGNo ratings yet

- Human Reproduction-L12 - May 16.pdf 2.oDocument69 pagesHuman Reproduction-L12 - May 16.pdf 2.oUpal PramanickNo ratings yet

- Anatomy: Cervical Disk DegenerationDocument5 pagesAnatomy: Cervical Disk DegenerationSUALI RAVEENDRA NAIKNo ratings yet

- Native Mitral Valve Fungal Endocarditis Caused 2024 International Journal ofDocument4 pagesNative Mitral Valve Fungal Endocarditis Caused 2024 International Journal ofRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Applied Anthropology: By: DR Habibullah Abbasi Assistant Professor Center For Environmental Science, UosDocument13 pagesApplied Anthropology: By: DR Habibullah Abbasi Assistant Professor Center For Environmental Science, UosZain MemonNo ratings yet

- SPMU FormDocument3 pagesSPMU FormHershey Ramos SabinoNo ratings yet