Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Myelodysplasia

Uploaded by

Jhon AlefeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Myelodysplasia

Uploaded by

Jhon AlefeCopyright:

Available Formats

Myelodysplasiadthe Musculoskeletal Problem:

Habilitation Erom Infancy to Adulthood

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

i%e physrcal therapy and orthopedic management of patients with myelodysphia Kimberly D Ryan

ji-om in.t~uyto adulthood are reviewed. T%eoverall goal for the child with myel- Christine Ploski

odv.phsia isfunctional independence.Pbysid therapy and orthopedic intaven- John B Emans

tion enable the individual to achieve this goal. &ociatedproblems, hhoweuer, sucb

as ArnolrCChiari maIformution, hydrocephalus, and tethered spinal cord, influ-

ence functional expectations. Pbysical therapy management begins in the neona-

talperiod and continues though adolescence. Treatment is mod@ed at the zlari-

ous stages of da~elopment.Knowledge of current orthotic and adaptiz~eequipment

is neces.uzly to achiez~eoptimal locomotorfunction. Orthopedic management deci-

sions are based on musculoskeletal and neurologic assessments, to which the phys-

ical thercrpist proz)ides a sign@cant contribution. Conm1enies e d t over the or-

thopedic management of dislocated hips, scoliosis, and kyphmis. [&an KD, Pl&i

C, Emans JB. Myeloci$sp&asia-the musculoskeletalproblem:habilitation ji-om in-

fancy to adulthood. Pbys 7;ber. 1991;71:935-946.1

Key Words: W p t i z ~ equipment,

e Function, Musculosheletal defmities, Myelociys-

phia, Orthotics, Strength.

Myelodysplasia, or myelomeningocele, The incidence of myelodysplasia var- weeks of gestation may decrease the

is a complex congenital disorder that ies in difFerent parts of the world but need for a subsequent amnio~entesis.~

primarily affects the nervous system is generally 1 per 1,000 births.2 A Amniocentesis performed at this time

and secondarily affects the muscu- slightly higher incidence is found in detects almost all open myelomenin-

loskeletal and urologic systems individuals of northern Europe origin. goceles but not closed (skin-covered)

(Tab. 1). The myelodysplastic defect There is a 1% to 2% greater chance myeloceles.6 Early detection may pre-

involves a failure of the fusion of the of a child being born with myelodys- sent a difficult decision for the par-

caudal end of the neural tube or rup- plasia if a sibling is already affected.3 ents, because termination of the preg-

ture of the nearly closed neural tube, nancy is the only way to prevent the

occurring early in embryonic devel- Prenatal screening can lead to early defect. Prior knowledge, however, can

opment before the 28th day of gesta- detection of the defect. Elevated levels prepare parents for the need for a

tion. The etiology is unknown but is of alpha-fetoprotein in the maternal cesarean birth and immediate postna-

believed to be multifactorial and in- serum after the 16th week of gesta- tal care.

cludes genetic and environmental tion may be indicative of a neural

influences.1 tube defea.4 Ultrasound testing per- Most infants born with myelodysplasia

formed between the 16th and 24th are treated aggressively with immedi-

ate closure and shunt insertion to

manage hydrocephalus,7 but this ap-

proach has not always been followed.

Kn Ryan, BS, PT,is Supervisor and Clinic Consultant, Department of Physical Therapy and Occupa- Lorher? in 1971, found that even

tional Therapy Services, Children's Hospital, 300 I.onpood Ave, Boston, MA 02115 (LISA). Addrehs

all correspondence to Ms Ryan. those children who were treated had

considerable problems with self-

C Ploski, MS, IT, PCS, is Assistant Supervisor and Clinic Consultant, Department of Physical Tiler.

apy and Occupational Therapy Services, Children's Hospital.

esteem and the attainment of func-

tional independence. He recom-

JB Emans, MD, is Aqsociate in Orthopaedic Surgey, Department of Onhopaedics, and Clinical Di- mended "selective treatment" based

rector, Myelodysplasia Clinic, Children's Hospital. He is also Assistant Clinical Professor, Depart-

ment o f Orthopedic Surgery, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138. on four criteria identified at birth: the

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12December 1991

-

Table 1. Basic Myelodysplastic Dgect L)ej?nitiom

Defect

Spina bifida occulta

Definltlon

Vertebral defect characterized by failure of closure of the

tral nervous system problems are of-

ten present.

Hydrocephalus. Evidence of hydro-

cephalus is present in 80% or more

of infants with myelodysplasia.l2 Clini-

cal symptoms are manifested by bulg-

posterior elements of the vertebral arch without a sac ing fontanel, increasing head circum-

containing neural tissue visible on the back. The ference, downward deviation of the

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

vertebral defect may or may not be associated with an eyes ("sunset eyes"), irritability, pro-

abnormality of the spinal cord. jectile vomiting, and seizures.

Spina bifida cystica Vertebral defect with cystic protrusion of the meninges or

of the spinal cord and meninges. Hydrocephalus is managed by the

Meningocele Protrusion of the meninges and cerebrospinal fluid into a insertion of a shunt, most commonly

sac that is covered by epithelium. Clinical symptoms a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.l3 Shunt

vary according to underlying spinal cord anomalies or

may not be apparent.

insertion may be performed when the

defect is closed or later when the

Myelomeningocele Most common and serious defect, which includes the

spinal cord, nerve roots, meninges, and cerebrospinal

symptoms of hydrocephalus are ap-

fluid. Commonly noted in the lumbar area, the level of parent. Revisions are necessary if the

the lesion is usually reflected in the severity of the shunt tubing becomes occluded, dis-

clinical deficit, with higher lesions having more connected, o r infected.

pronounced deficits.

Lipomeningocele Vertebral defect associated with a superficial fatty mass Some st~diesl4~15 have shown that

that merges with lower levels of the spinal cord. children with hydrocephalus may

Neurologic deficits vary. There is no associated

hydrocephalus. have reduced intelligence and

Encephalocele A protrusion of scarred brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and

perceptual-motor impairments. More

meninges through a bony defect in the skull. This recently, however, Mapsstone and

defect is usually occipital, but can be frontal or through colleaguesl6 demonstrated that intel-

the skull base. lectual function is also affected by

Anencephaly Failure of fusion of the cranial end of the neural tube, complications from shunting and by

resulting in exposure of a malformed brain at birth. other central nervous system anoma-

lies. Advances in shunt-placement

techniques and infection control have

degree of paralysis, the degree of in- nurse, physical therapist, occupational improved the outcome. Perceptual-

creased head circumference, the pres- therapist, social worker, and orthotist. motor impairment affects school per-

ence of kyphosis and other associated We believe the availability of a nutri- formance. Evaluation for perceptual-

congenital anomalies, and birth inju- tionist, speech and language patholo- motor dysfunction is frequently

ries. Gross and colleagues? using cri- gist, and psychologist is also essential handled by an occupational therapist.

teria similar to the criteria used by for comprehensive management.

Lorber, as recently as 1983 also sug- Arnold-Chiari malformation, In the

gested that treatment be withheld for The purpose of this article is to re- Arnold-Chiari defect, the lower brain

some infants. Most authorities today, view current physical therapy and stem and cerebellum, including the

however, agree that children with orthopedic management of children fourth ventricle, herniate through the

myelodysplasia should be treated ag- with myelodysplasia from infancy foramen magnum into the spinal ca-

gressively to minimize neurologic through adolescence. A philosophy nal. The fourth ventricle may become

deficits. In recent years, improved and controversies of care will be obstructed and the flow of cerebro-

closure techniques and other mehcal addressed. spinal fluid impeded, resulting in

advances and increa~edsocietal ac- hydrocephalus.17

ceptance of the disability have con- Associated Problems

tributed to a better quality of life for Virtually every child with myelomen-

these individuals.lO Neurologic Deficits ingocele has the malformation, and its

presence and severity are confirmed

Optimal management of the child with The primary neurologic problems in by magnetic resonance imaging

myelodysplasia occurs in a clinical set- persons with myelodysplasia are the (MKI), as well as the presence of clini-

ting with a team of knowledgeable variable motor and sensory deficits, cal manifestations.le Clinical signs in-

profe~sionals.~lThe treatment team which will be discussed in detail in clude respiratory symptoms, such as

should include a neurosurgeon, ortho- the "Physical Therapy and Orthopedic apnea, stridor, vocal cord paralysis,

pedic surgeon, urologist, pediatrician, Management" section. Associated cen- and upper-extremity weakness or

spasticity. A shunt insertion or revi-

68 / 936 Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12/December 1991

sion is the usual management tech- introduced by muscle imbalances, levels of involvement, As foot sensation

nique, but severe cases occasionally static positioning and gravity, and is often incomplete, neurotrophic ul-

require cervical laminectomy and pos- weight bearing on joints with insuffi- ceration can become a problem and

terior decompression.'9 cient muscular support. The source of may interfere with ambulation.

the deformity should be determined

Syrlngomyella and hydromyelia. before intervention, because the suc- Spinal deformities. Scoliosis and

Syringomyelia is present if there is a cess of treatment can be hindered by kyphosis have many etiologies in chil-

dilatation of the central canal of the a changing neurological picture, such dren with myelodysplasia. In addition

spinal cord, resulting in an elongated as the progressive deformities seen to abnormal skin covering and dis-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

cavity (syrinx) within the spinal cord with a tethered spinal cord. placement of neural elements, the

filled with cerebrospinal fluid.20 Hy- bony spine is abnormal. The stabiliz-

dromyelia o r syringohydromyelia are Lower extfemlties. Hip subluxation ing effect of the paraspinal muscles is

other terms commonly used for this and dislocation are common.27 They often lost, because the muscles are

condition. Symptoms such as the de- may be present at birth or develop displaced laterally o r may be dener-

velopment of scoliosis, upper- with growth because of the unbal- vated. In individuals with kyphotic

extremity weakness, or sensory anced action of the hip flexors and deformities, the muscles may be ante-

changes may occur if the syndrome adductors. Hip flexion contraaures rior as well as lateral to the spinal

progresses. The treatment is compli- also occur frequently. column. Spinal deformities may result

cated and varies according to the eti- from unbalanced growth attributable

ology of the syrinx.21.22 Knee flexion contractures occur in to congenital abnormalities (congeni-

children with high neurosegmental tal scoliosis or kyphosis), from abnor-

Tethered spinal cord. Progressive levels of involvement,2%nd such con- mal stresses of pelvic obliquity or hip

neurologic dysfunction may indicate traaures may impede the use of contracture, or from paralytic col-

tethering of the conus medullaris and braces or a standing frame. Progres- lapse. Significant scoliosis in a struc-

lower spinal cord ro0ts.~3Tethering sive knee flexion deformities may also turally normal part of the spine or a

results from scar formation and bind- accompany spasticity (hypertonia) rapid increase in spinal deformity

ing of the spinal cord tissue to the resulting from a tethered spinal cord. may result from spinal cord tethering

bony column at the site of the initial Ambulatory individuals with strong or other neurologic problems.24

repair, with subsequent inhibition of ankle dorsiflexors but weak gastroc-

normal spinal cord movement with nemius muscle function may develop Bowel and

growth or activity. A clinical diagnosis knee flexion deformities from a Bladder Problems

is made based on deterioration of crouched stance. Knee hyperexten-

urologic hnction, progressive ortho- sion deformities and rectus femoris The child with myelomeningocele may

pedic deformities, changes in motor muscle contracture can result from experience problems with bladder

status, back or leg pain, or deteriora- strong quadriceps femoris muscle control, which may adversely affect

tion in gait. Usually, the change in function unopposed by hamstring renal f~nction.~9 Clean, intermittent

motor fiunction entails loss of muscle muscle activity. Hypertrophy of the catheterization, in combination with

strength, although muscle activity not sartorius muscle secondary to overuse pharmacologic agents, has enabled

previously seen and not under volun- can be accompanied by a functionally most children to become c0ntinent.~9

tary control may also appear. Surgical insignificant snapping of the muscle Urodynamic studies are performed in

untethering is performed to halt the as it glides across the medial knee the neonatal period and at regular in-

progression of the symptoms, but is structures. Patellofemoral overuse syn- tervals as the child matures. The re-

not always successful.24Existing defor- dromes are common in community sults provide baseline information that

mities or problems may persist and ambulators with low-lumbar neuro- is useful in predicting future function

require orthopedic intervention. segmental levels of involvement, who and in detecting changes that may indi-

rely heavily on their quadriceps femo- cate neurological deteri0ration.3~

Musculoskeletal Problems ris muscles, particularly if a knee flex-

ion contraaure is present. Fecal incontinence affects the child's

A variety of bone and joint deformi- self-esteem and social acceptance.31

ties that affect function are encoun- Congenital foot deformities (eg, club- Management includes a combination

tered in children with myelodysplasia. foot, vertical talus) are most common of regular toileting, diet, medica-

Afected extremities usually exhibit in children with mid-lumbar neuroseg- tion, biofeedback, and behavior

muscle atrophy and osteopenia. To- mental levels of involvement. Acquired modification.-'2

gether, osteopenia, limited joint pro- foot deformities such a5 talipes calca-

prioception, and resistant contractures neus, talipes cavus, and talipes plano- Physical Therapy Assessment

make fractures a frequent occur- valgus, which develop from unbal-

rence.25J"ome deformities are con- anced muscle forces and unsupported A comprehensive evaluation includes

genital, but the majority are acquired weight bearing, occur most commonly testing range of motion (ROM), pos-

through growth and abnormal forces in children with lower neurosegmental ture, sensation, muscle strength, de-

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number

tantly, identlfy areas that may be at

risk for skin breakdown. The pres-

ence of any joint or postural deformi-

ties further increases the risk for skin

breakdown in insensate areas because

of unequal weight bearing.

The behavioral state of the infant af-

fects the sensory testing, which

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

should normally b e performed when

the infant is quiet. The infant's medi-

cal status and the effects of any medi-

cations must b e considered. Reactions

to appropriate stimuli that may indi-

cate intact sensation include grimac-

ing, crying, or withdrawal from the

stimulus. We believe sensory testing

becomes more accurate and precise

at later ages. Light touch, position

sense, temperature, and two-point

discrimination, in addition to pain,

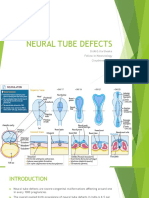

Figure 1. Newbonz infant with myelodyspkzsiu and kydrocephalus afer closure. can b e assessed in the older child.

Note abduction; externulfy rotatedposition of hips; and donijlexed, everted position of

thefeet. Strength

velopmental reflexes, motor develop- who is unable to assume test positions The results of the initial and subse-

ment, and functional status. Qualitative because of deformity or discomfort. quent muscle examinations are used

and quantitative assessments are used to idenufy the d e c t e d neurosegmen-

to assess motor development, identify The interpretation of the results of the tal levels and to predict the functional

strengths and weaknesses, and provide joint ROM mea5urement should al- outcome (Tab. 2 ) . e 4 3 Realistic inter-

a basis for intervention. Abnormal or ways be based on the individual's age, ventions are determined based on the

immature patterns of movement and muscle strength, and potential func- upper- and lower-extremity muscle

any asymmetries should also be docu- tional status. For example, in neonates strength in combination with the

mented. Both upper and lower ex- and young infants, limitations of hip child's dwelopmental level.

tremities are tested because associated and knee extension and hip adduc-

central nervous system problems can tion are normal and do not necessar- The procedure and grading for mus-

s e a the upper extremity and dec't ily indicate a problem.39 If there is an cle testing must be modified in in-

Assessments are

mobility.'X~2~).~*..'5-36 accompanying muscle imbalance or fants and young children according to

repeated at intervals ranging from the limitations persist over time, how- their age and dwelopmental level, as

1 month to 1 year, according to the ever, the findings should be consid- well as their medical stat~s.~*.*5

age and needs of the child. Results of ered abnormal. Grades that have resistance as a crite-

sequential examinations allow conlpar- rion, Fair plus o r above,G may b e

isons to determine the rate of prog- difficult to assign, because the infant

ress, to detect changes that may be or young child is unable to cooperate

indicative of deterioration, and to Alignment of the trunk and extremities or to understand the concept of resis-

judge the effectiveness of interventions. should be assessed through palpation tance. If an infant resists passive

The findings within each test area of bony landmark5 and observation. movement, however, the muscle

should be interpreted separately as Asymmetries and deviations from nor- strength may be graded as at least

well as jointly when impressions of mal are recorded. Real and apparent Fair plus. In a young child, the ability

status, prognosis, and physical therapy leg-length discrepancies may be indica- to lift body weight in an activity such

intervention are formed. tive of a dislocated hip, pelvic obliq- as bridging can be used to determine

uity, or scoliosis. Abnormal findings, whether the strength of the gluteus

Range of Motion particularly if new or progressive, war- maximus muscle is above the Fair

rant orthopedic assessment. level.

Standard test procedures have been

established for measurement of joint The initial muscle examination is usu-

ROM37.38 Modifications are necessary ally performed following closure of

in the neonate who may have position The results of sensory testing establish the defect, once the infant is medi-

restrictions (Fig. I ) or for any child the sensory level and, more impor- cally stable. The infant is usually re-

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12mecember 1991

-

Table 2. Function in Myelody.~lasia

Neurosegmental

Level Muscles Innervated

Preembulatlon Ambulatlon

Orthosls Orthoslsa Aselstlve Devlce Functlonal Prognosls

Musculoskeletal

Problem

Thoracic Abdominal Standing frame Reciprocating gait Parallel bars Wheelchair Spinal deformity

orthoses, swivel I

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

walker, Walker

parapodium I

Forearm crutches

Upper lumbar Abdominal, hip flexors Standing frame Reciprocating gait Parallel bars Wheelchair Hip flexion

orthoses, I contractures

parapodium Walker Possible household or Spinal deformity

I therapeutic

Forearm crutches ambulation

Standing transfers

Mid lumbar Abdominal, hip flexors, None HKAFO Parallel bars Wheelchair for Hip dislocation,

knee extensors, hip I I community mobility or subluxation

adductors KAFO Walker orthoses for

I I household ambulation

AFO (depending Forearm crutches

on quadriceps

femoris muscle

strength)

Low lumbar Abdominal; knee None KAFO Parallel bars Household or Foot deformities

extensors; hip I I community ambulators

abductors and AFO Walker

adductors; knee, hip, I

and toe flexors; ankle Forearm crutches

and toe dorsiflexors, I

evertors, and invertors None

Lumbosacral Abdominal; ankle plantar None AFO, UCBL, or Walker Community ambulators

flexors; foot intrinsic none I

muscles; knee None

extensors; hip

abductors and

adductors; knee, hip,

and toe flexors; ankle

and toe dorsiflexors,

evertors, and inventors

"HWO=:hip-knee-ankle-foot orthosis; WO=knee-ankle-ftmt onhosis; tu;O=ankle-foot orthosis; FO=foot onhosis; lJCRI.=University of California Bio-

mechanic:< Laboratory shor insen.

stricted to the prone o r side-lying po- be palpated for contraction in order elicit muscle contractions. The pres-

sition in order to allow the back to to differentiate between the activity of ence of muscle activity with reflex

heal. If hydrocephalus is present, individual muscles and muscle stimulation only should be docu-

there may be further restrictions o n groups. Tactile stimuli in the area of mented, but does not necessarily indi-

upright positioning. Once the posi- the deficits as well as at sites inner- cate voluntary control.

tioning restrictions are discontinued, vated by nerves from levels above the

the infant's strength can b e assessed spinal defect are used to elicit move- Modifications of muscle testing proce-

in the supine and upright positions. ment. Positioning a joint o r joints in dures are also necessary for testing

extreme KOM (eg, maximum hip and the older infant and young child. De-

The infant should be awake and alert, knee flexion) may stimulate the infant velopmental activities, such as rolling

which is often just prior to feeding. to contract the antagonist. Responses to elicit hip flexion o r pulling to a

Resting posture is observed as well as such as the plantar-grasp o r equilib- standing position to determine quad-

spontaneous movement. Muscles must rium reactions may also be used to riceps femoris muscle function, may

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12/December 1991 939 / 71

be used. The use of traditional tech- motor level and associated neurologic Physical Therapy and

niques of muscle testing depends on or orthopedic problems should be Orthopedic Management

the child's ability to cooperate and included in the interpretation of the

follow directions, but, in our experi- overall scores. The overall goal of orthopedic and

ence, these techniques can usually be physical therapy management is the

used by the age of 4 years. Hand-held The achievement of specific develop- habilitation of the child by maximizing

dynamometers have also been used in mental milestones has implications the child's function, independence,

pediatric populations to assess muscle for decisions regarding orthopedic and self-esteem while minimizing fam-

strength.47 Strength assessments intervention. For example, if an infant ily stress. Specific goals for each child

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

should be performed every 6 months has not achieved adequate sitting bal- are formulated, depending on the re-

in the growing child and yearly in the ance by the age of 10 months because sults of the assessment. Conservative

adolescent to monitor for changes. of trunk instability, a spinal orthosis or nonsurgical treatments include

may be a treatment option. Con- physical therapy, casting, bracing, and

Developmental Reflexes and versely, if an infant has not developed splinting. We believe that carefully

Postural Reactions good head control, surgical interven- planned surgical interventions may

tion to decrease lower-extremity con- save unnecessary casting or bracing

Procedures have been established for tractures and to allow use of an am- and may help foster independence.

testing developmental reflexes and bulatory device may not be

postural reaction^.^^^* The presence appropriate. The Neonate

or absence of certain responses may

have a direct influence on gross mo- Functional assessments are used to Physical therapy management of the

tor skills50 and, therefore, treatment determine the readiness and need for neonate is usually initiated in the pe-

decisions. For example, we believe adaptive equipment such as bracing. riod immediately following closure of

the attainment of independent upright These assessments are also used to the back defect. General objectives

stance cannot be achieved without determine the older child's ability to include increaqing ROM and active

effective righting and equilibrium re- function in various environments movement and promoting the achieve-

actions or in the presence of certain (eg, school, home). Functional assess- ment of developmental milestones.

primitive reflexes. The physical ther- ments include evaluations of gross

apy program often includes tech- motor abilities, mobility, and self-care Early treatment is limited by the in-

niques to facilitate more mature reac- activities. Assessment of motor abili- fant's medical status and position re-

tions while inhibiting the primitive ties includes a description of the strictions, which are dependent on

responses. child's ability to move into, within, the type of closure, rate of healing,

and out of various positions and to postoperative complications, the man-

Development and Function maintain those positions, as well as a agement of hydrocephalus, and the

description of the child's ability to physician's judgment. Prone and side-

The rate of development of motor function within each position. Assess- lying positioning are usually allowed

skills is slower in children with my- ment of mobility includes an evalua- before supine positioning. When the

elodysplasia than in children without tion of gait, wheelchair activities, and infant can be positioned supine and

myelodysplasia and is related to the transfers. If the child is ambulatory, upright, the developmental program

neurosegmental level that is affected.51 the type of gait (eg, reciprocal, swing- can be expanded.

Medical problems, such as shunt in- through), gait deviations, use of assis-

fections, may result in regression or tive devices, and level of ambulation56 We believe that appropriate tactile,

delay of motor development.52 (eg, household, community ambula- visual, and auditory stimuli should be

tor) should be described. The ability introduced to facilitate movement and

Developmental testing is frequently and ease with which the child ambu- development. Passive exercises, facili-

used for the infant and young child. lates or maneuvers a wheelchair on tation of active movement, and posi-

Developmental tests that are standard- various terrains and levels and the tioning techniques are used to op-

ized (ie, norm or criterion refer- child's endurance are also assessed. pose any contractures and muscle

enced) provide quantitative, objective Activities of daily living include hy- imbalances.

information about motor abilities.53-55 giene activities (eg, toileting, bathing,

Scores from standardized tests docu- slun care), feeding, and dressing. The Parent education is a major focus. The

ment the degree of developmental child's level of independence and role of and rationale for physical ther-

delay and may be required in order need for adaptive equipment should apy are explained. Parents are in-

to justify the need for intervention. be noted. structed in a home program that in-

Modifications may be necessary when cludes exercises, positioning and

administering and scoring test items, handling techniques, and appropriate

particularly if the child uses adaptive developmental activities. Skin-care

equipment. Statements regarding the instructions are also given, and stan-

influence of factors such as the child's dard child care equipment is modi-

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12December 1991

fied, if needed. Follow-up visits are In our view, as many procedures as the presence of quadriceps femoris

arranged prior to discharge, and re- possible should be performed during muscle function makes community

ferrals are made to local treatment the same hospitalization or same op- ambulation a possibility. Unopposed

programs. erative session. We attempt to com- hip adductors and flexors tend to pro-

plete all orthopedic surgeries prior to duce progressive subluxation and

The Infant age 5 years, in order to minimize in- eventual dislocation. Management of

terference with schooling. subluxations in these individuals is an

During infancy, attainment of age- area of considerable controversy. In

appropriate developmental motor Orthopedic management of hip the infant, abduction splinting and

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

milestones is emphasized. Achieve- deformltles. Treatment of hip dislo- stretching will help maintain ROM

ment of upright stance is the overall cation in children with myelodysplasia and may facilitate acetabular and fem-

goal. Aclivities are incorporated into is individualized and differs greatly oral development. As subluxation and

the program to facilitate head and from the management of congenital dislocation gradually develop, a deci-

trunk control in the developmental hip dislocation in children without sion must be made as to whether to

positions. Prone activities are used to myelodysplasia or the management of treat the hip dislocation. If the child

increase upper-extremity strength. paralytic dislocation in children with has little ambulatory potential because

Early mobility through rolling, belly spastic cerebral palsy. Hip subluxation of neurologic problems, reduction is

crawling, and quadrupedal creeping is in myelodysplasia, unlike that in spas- not indicated and muscle releases are

encouraged and facilitated, because tic cerebral palsy is generally not as- performed as needed to maintain

these achievements provide the foun- sociated with pain. The presence of ROM. If there is good ambulatory po-

dation h3r future motor progress. Pos- dislocation or subluxation noted on a tential, as indicated by the presence of

tural and balance reactions are facili- radiograph is less important than a strong quadriceps femoris muscula-

tated, because they are prerequisites maintenance of hip joint motion and ture, and in the absence of other

for independent standing. Kighting avoidance of joint contractures. Treat- complicating factors, then the child is

and equilibrium reactions will also ment generally depends on the child's a potential candidate for surgical treat-

help strengthen the neck and trunk ambulatory potential, which correlates ment of the hip subluxation.

musculature and promote indepen- best to the neurosegmental level of

dent sitting. Modifications in seating involvement.56.5~59 Proponents of hip reduction and mus-

may be needed if the child has a se- cle transfer argue that optimal ROM is

vere kyphosis or lacks appropriate Hip subluxation occurs infrequently achieved by hip reduction.6D-G*Better

head and trunk control. with lumbosacral neurosegmental posture and gait mechanics may result

levels of involvement, but is usually from keeping the hips reduced and

The Preschool-Aged Child treated aggressively because of the from associated muscle transfers. Op-

excellent ambulatory potential of ponents of hip reduction believe that

Physical therapy has an active role at these children. In individuals with operative reduction exposes the child

this time, particularly in assisting the thoracic or upper-lumbar neuroseg- to the risk of hip stiffness without

child in attaining some form of inde- mental levels of involvement, commu- functional benefit and that soft tissue

pendent mobility. As the child begins nity ambulation is not anticipated be- releases alone are sufficient to main-

to pull to a standing position, ortho- yond childhood. Because little tain ROM and ambulatory ability.6HH

pedic intervention may be needed to demand will be placed on the hips,

achieve upright stance. Intervention contracture releases are performed as Studies56,6%8 have shown no correla-

may include bracing, casting, bony or needed to maintain ROM. We believe tion between the level of ambulation

soft tissue procedures around the hip, surgical reductions, osteotomies, and and the status of the hips in cluldren

and release of contractures that inter- muscle transfers are generally not with mid-lumbar neurosegmental lev-

fere with function. Treatment of foot indicated, because the benefits do not els of involvement. Because other fac-

deformities must be individualized. In outweigh the risks of postoperative tors, such as severe hydrocephalus,

our experience, in spite of casting stiffness or heterotopic ossification. A Arnold-Chiari malformation, obesity,

and stretching, most severe foot de- severe postoperative hip contracture motivation, and contractures, also in-

formities will require surgery. A plan- may prevent the patient from assum- fluence ambulation, the results of

tigrade, supple, braceable foot is the ing either a sitting or standing posi- these studes remain somewhat

goal. tion. We also believe a mobile, dislo- inconclusive.

cated hip is preferable to a stiff,

General principles of surgical treat- reduced hip, particularly in the non- If the decision is made to relocate the

ment include correction of bony de- ambulatory patient. hips, open reduction with capsulor-

formity and balancing of muscle rhaphy is generally required." Pelvic

forces. With the use of internal fixa- There is a relatively high incidence of or femoral osteotomy, or both, may

tion, postoperative immobilization is hip subluxation in children with mid- also be necessary. Because the iliop-

kept to a minimum to diminish 0s- to low-lumbar neurosegmental levels soas and adductor muscle groups are

teopenia and subsequent fracture^.^' of i n v ~ l v e m e n tIn

. ~these

~ individuals, largely unopposed in these children,

Physica.1 TherapyNolume 71, Number 12/December 1931

learn to release the joints of the para-

podium. We therefore prefer the

I I standing- frame, which is less expen-

sive and easier to apply.

Time spent in the standing frame de-

pends on the child's tolerance and

skin integrity. Once the desire to

move in the frame is evident, consid-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

eration is given to orthotic devices

that allow more functional ambula-

tion. The overall goal is to provide

maximum mobility with the minimum

amount of bracing.73

The reciprocating gait orthosis (RGO)

is used for children with thoracic and

high-lumbar neurosegrnental levels of

involvement as young as 18 months of

age. Some practitioners prefer to wait

until the children are 30 to 36 months

of age before prescribing the RGO

(see article by Knutson and Clark in

this issue). Individuals using the

RGO are more likely to achieve

household ambulation and remain

functional longer than if they used

Figure 2. Standing pame: (A) anterior view; (B) adqpted to accommodate chiki's other braces.74~75

leg-lengthdiscrepancy and tendency to lean to the right.

some attempt is usually made to bal- Orthotlc management. Some de- General guidelines have been estab-

ance the musculature, or dislocation gree of contracture may be accommo- lished for determining appropriate

will gradually recur. Most procedures dated by orthoses. Surgical release, orthoses for functional mobility (see

include adductor release or posterior however, is indicated to facilitate or- article by Knutson and Clark in this

transfer of the adductor origin.@Lat- thotic management if hip flexion con- issue). Hip-knee-ankle-foot orthoses

eral transfer of the external oblique tractures are greater than 30 degrees, (HKAFOs), knee-ankle-foot orthoses

muscle to the greater trochanter70 to knee flexion contractures are greater (KAFOs), ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs),

provide stabilizing force is now widely than 20 degrees, and plantar-flexion and foot orthoses (FOs) are pre-

used. Another approach comists of deformities are greater than 10 scribed, depending on the child's

lateral transfer of the iliopsoas muscle, degrees. neurosegmental level of involvement.

through a hole created in the wing of The pelvic band of the HKAFO assists

the ilium, to the greater trochanter.71 We believe all children, except those in the control of hip abduction, ad-

This transfer alleviates the deforming with severe central nervous system duction, and rotation during gait. If

force of the iliopsoas muscle and pro- involvement, should be given the op- placement of the lower extremity is

vides a tenodesis or active hip abduc- portunity to be upright, regardless of not a problem, a KAFO may be used

tion. Both approaches have their advo- their functional prognosis. This phi- for individuals with little or no quad-

cates. Many feel the external oblique losophy is based on the premise that riceps femoris muscle strength. An

muscle transfer allows better ambula- weight bearing increases bone densi- AFO or FO is indicated if foot and

tion and does not diminish the pa- ty,72 helps to maintain urinary tract ankle support are needed.

tient's ability to flex the hips and climb function, and develops self-esteem.

stairs (RE Lindseth, L Dias; personal Functional mobility. Gait training is

communication), although follow-up Either a parapodium or a standing initiated in the parallel bars. Activities

studies of iliopsoas muscle transfers d o frame (Fig. 2) can be used as the first to develop balance and the ability to

not show impairment in climbing orthosis for the child with a neuro- weight shift are utilized. Progression

stairse63Others feel iliopsoas muscle segmental level of L-3 or above to to either an anterior- or reverse-facing

transfer is more likely to ensure main- achieve upright stance and early mo- (posterior) walker is made once inde-

tenance of reduction. Tailoring treat- bility. The swivel walker, parapodium, pendent ambulation in the parallel

ment to the individual child is crucial and standing frame may also be used bars is achieved. We prefer the

and must be based on a realistic as- for long-term mobility. We have reverse-facing walker whenever possi-

sessment of walking potentd. found, however, that few children ble, as it promotes better postural

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12December 1991

Chronic skin breakdown over the ky-

photic area may result from pressure

against the back of a chair, friction dur-

ing wheelchair use, or irritation from

pelvic bands. Compensatory thoracic

lordosis may develop above the thora-

columbar kyphosis and can cause res-

piratory dficulties. Care of abdominal

ileal loops or colostomies becomes

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

diflicult when the child is collapsed

forward into kyphosis and the contour

of the abdomen is distorted. The

child's body image may be severely

altered by the trunk distortion accom-

panying severe kyphosis.

Brace or cast treatment of congenital

kyphosis or collapsing kyphosis rarely

stops progression of the deformity

and frequently contributes to skin

breakdown. Orthoses, nevertheless,

can improve sitting posture and bal-

ance, particularly in individuals with

flexible collapsing kyphosis.

Figure 3. Twoyear-old boy with rec* routing gait orthosLs, reuene-facing walker,

and wbet?lcbair. The most common surgical procedure

when kyphosis is present in individu-

alignment than does the anterior- ence in the ultimate level of wheel- als with paraplegia is excision of the

facing walker.76 If a reverse-facing chair skill or ambulation. deformed spinal segment (kyphec-

walker is selected for a child, the tomy) and the nonfunctional cord at

depth should be sufficient to allow We introduce the wheelchair as early the level of the kyphosis.78 The re-

posterior clearance for orthoses that as 18 months of age if it is apparent maining relatively straight upper- and

have pelvic components. Once the that this device will enhance mobility lower-spine segments are united by

child is able to maintain standing bal- and independence. Early introduction instrumentation and fusion. This pro-

ance and ambulate confidently with usually enables children to keep up cedure effectively removes the kypho-

the walker without assistance, forearm with their peers. In our experience, sis, but results in a shorter-than-

crutches may be introduced. early wheelchair use has not led to normal trunk. Growth over the fused

the cessation of ambulation, even in spinal segment is halted; hence, this

Independent mobility by walking is marginal ambulators. Rather, the procedure is delayed, if possible, until

the goal during early childhood. In boost in self-confidence and indepen- late childhood. Care must be taken

our experience, however, many chil- dence that may accompany wheel- when excising the nonfunctional cord

dren will require a wheelchair to im- chair use seems to increase their ac- to ensure that bladder function will

prove access to the environment, de- tivity level and overall mobility. We not be adversely affected, because

spite optimal bracing and gait training view the wheelchair as an aid to mo- some individuals have a functioning

(Fig. 3). Considerable controversy ex- bility and do not believe that its use sacral cord in spite of no lower-

ists surrounding the timing of the in- represents a "failure" of management. extremity motor function.

troduction of a wheelchair for children

who are unlikely to achieve indepen- Orthopedic management of ky- The School-Aged Chlld

dent community ambulation. The pro- phosls. Seating arrangements and

ponents of early wheelchair introduc- bracing will be complicated by the Because most children with myelodys-

tion have argued that early training presence of a kyphotic deformity. plasia are mainstreamed in public or

will maximize eventual wheelchair Some children, generally those with private schools,79 physical therapy

skills. The opposing view is that early low-thoracic or high-lumbar level of programs during childhood are based

introduction limits the child's ambula- paralysis, have a severe congenital in the school. Senices may be direct,

tory potential. Mazur and colleagues,n kyphosis or a collapsing thoracolum- indirect, or consultative, but the over-

in a recent comparative study of two bar kyphosis. These deformities nor- all goal of functional independence

groups td patients, found that the tim- mally increase with growth and com- remains unchanged. Activities of daily

ing of the introduction made no differ- monly result in functional and living, such as dressing and brace

cosmetic difficulties. management, as well as continued

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 121December 1991

work on mobility skills, are addressed individuals are able to stand and walk pressure-relief maneuvers. Skin ulcer-

during the school years. independently by virtue of a mobile ation has a major effect on the adoles-

hyperlordotic lumbar spine, which cent's function, because treatment may

Orthopedic management of scoli- may be compensatory for existing hip require surgical intervention, lengthy

OS~S. In late childhood and early ado- flexion contractures. Mobility of the hospitalizations with restricted posi-

lescence, the effects of progressive trunk and trunk musculature may be tioning, and major financial and per-

scoliosis may become apparent. Non- used to assist lower-extremity move- sonal costs, such as decreased peer

ambulatory individuals with severe ment in gait, such as with the RGO. and family interaction.%

scoliosis sit with their trunk out of Fusion resulting in the loss of lumbar

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

balance in relation to their pelvis. lordosis will accentuate existing hip Preparation for transition to adult-

They may require the use of one o r flexion contractures and make upright hood takes place during late adoles-

both upper extremities to maintain stance more dficult. In turn, in- cence. The adult with myelodysplasia

their sitting balance and may need creased weight bearing on the upper faces problems with separation from

extensive adaptive seating. Pressure extremities may be required. A retro- family, locating independent living

from unequal weight bearing during spective study by Mazur et a1,81 indi- arrangements, developing vocational

sitting increases the likelihood of ul- cated that nearly one third of ambula- skills, and finding appropriate medical

ceration. In our experience, bracing tory individuals who underwent ~are.~5.% The more prepared the ado-

has limited usefulness in preventing spinal fusion lost a functional level of lescent, the easier the transition. The

progressive scoliosis and the need for ambulatory ability. therapist may help by visiting the pro-

eventual surgery. For the child who posed living and vocational environ-

has difficulty with trunk control, how- The Adolescent ments and making suggestions for

ever, bracing may help to improve accessibility. If medical care is to be

balance and therefore upper- The energy cost of ambulation is high assumed under adult services, com-

extremity function. in adolescents with thoracic and high- munication by the treatment team

to mid-lumbar neurosegmental lev- who has monitored the individual will

Surgery for scoliosis is complicated els.82 Body weight, which usually in- ensure an easier transition.

by the presence of rigid bony defor- creases at this time, contributes to the

mities, deficient skin coverage, soft difficulties.H3 Arnbulation becomes less Summary

bone, and lack of posterior bony ele- eflicient in adolescence, and it be-

ments. Combined anterior and poste- comes more difficult for the adoles- The physical therapist and orthopedist

rior fusion and segmental instrumen- cent to keep up with peers. The ado- have a significant role in the assess-

tation has made surgical correction, lescent, therefore, may choose the ment and treatment of the child with

instrumentation, and fusion more pre- wheelchair for full-time functional myelodysplasia. Care of the individual

d i ~ t a b l eInfection,

.~~ loss of correc- mobility. Ambulation is usually done with myelodysplasia is a complex pro-

tion, neurologic injury, and failure of for therapeutic reasons only, with cess and continues throughout life.

fusion remain common complications. standing used for the purpose of Because the neurologic deficit may

Stronger segmental instrumentation transfers. change over time in some individuals,

has improved correction and often treatment programs must be individu-

allowed the child to be brace or cast Adolescents with lower neurosegmen- alized and flexible. The nature and

free in the postoperative period. tal levels of involvement may request a timing of various interventions may

wheelchair for community mobility vary. The needs and status of the indi-

Correction of scoliosis in the individ- and for participation in sports. We be- vidual, the level of function, and stage

ual who is nonambulatory equalizes lieve participation in sports should be of life should be considered.

weight bearing on bony areas for sit- encouraged, not only for the beneficial

ting and minimizes the likelihood of effects on coordination and trunk and Acknowledgments

ulceration. Care must be taken to upper-extremity strength, but also for

maintain lumbar lordosis. Obliteration the benefit of self-esteem. Many ado- We thank Alice Shea, ScD, PT,

of the lordosis will cause the individ- lescents enjoy athletic aczivities such as R Michael Scott, MD, Director of the

ual to sit more posteriorly on the is- basketball, tennis, weight Ilfting, swim- Section of Pediatric Neurosurgery,

chii and sacrum and may actually in- ming, and wheelchair racing. and James Koepfler, medical photog-

crease seating problems. rapher, all of Children's Hospital, Bos-

Because wheelchair use may increase ton, Mass, for their assistance in pre-

Ambulatory individuals may find it in adolescence, daily skin inspection paring the manuscript.

difficult to be mobile if they are con- and frequent push-ups to unweight the

stantly worlung to maintain their bal- buttocks are imperative. Special wheel-

References

ance when upright. The complex rela- chair cushions are used to promote

tionship between the pelvis and the equal weight distribution and provide 1 Caner CO, Spins b i f i h and anencephaly:

a

spine should be taken into account a firm base of support for the pelvis; problem in genetic-environmental interaction.

J BiOSOC "I'. 1969;1:71-83,

when considering spinal fusion. Some however, they do not take the place of

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12December 1991

2 Shurtleff DB, Lemir RJ, Warkany J. Embryol- 20 Hall W , Campbell RN. Myelomeningocele surements over time. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.

ogy, etiology, and epidemiology. In: Shurtleff and progressive hydromyelia, J Neuroswg. 1986;67:855-861.

DB, ed. MLyelodyspIasiasand Exhophies: Signif- 1975;43:457463. 41 Asher M . Olson J. Factors affecting the am-

icance, Prevention, and Treatment. New York, 21 Barnea WM, Foster JB, Hudgson P. S p i t - bulatory status of patients with spina bifida

NY: Grune & Stratton Inc; 1986:3944. gomyelia: Major ProbIems in Neuroswgery. cystica.J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1983;

3 Lipman-Hand A, Fraser FC, Cushman Biddle Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1973:vol 1. 65:350-356.

CJ, Indications for prenatal diagnosis in rela- 22 Barbaro NM, Wilson CB, Gutin PH, Ed- 42 DeSouza L, Carroll N. Ambulation of the

tives of patients with neural tube defects. wards MS. Surgical treatment of syringomyelia: braced myelomeningocele patient. J Bone

Obstet Gytlecol. 1978;51:72-76. favorable results with syringoperitoneal shunt- Joint Surg [Am]. 1976;58:1112-1118.

4 Alan LD, Donald I, Gibson AA, et al. Amni- ing. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:531-538. 43 Mazur JM, Menelaus MB. Neurologic starus

otic fluid alpha-fetoprotein in the antenatal 23 James CCM, Lassman LP. Spinal dysra- of spina bifida patients and the orthopedic

diagnosis of spina bifida. Lancet. 1973;2:

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

phism: the diagnosis and treatment of progres- surgeon. Clin Orthp. 1991;264:54-64.

522-525. sive lesions in spina bifida occulta. J Bone 44 Kendall FP, McCreary EK. Muscles: Testing

5 Nadel AS, Green JK, Holmes LB, et al. Ab- Joint Swlq [Br] 1962;44:82&840. and Function. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams

sence of need for amniocentesis in patients 24 Schmidt D, Robinson B, Jones D. The teth- & Wilkins; 1983.

with elevated levels of maternal serum alpha- ered spinal cord: etiology and clinical manifes- 45 Zausmer E. Evaluation of strength and mo-

fetoprotein and normal ultrasonographic ex- tations. Orthopedic Rm'ew. 1990;19:87@876. tor development in infants: parts 1 and 11. Phys

aminations. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:557-561. 25 Katz JF. Spontaneous fractures in paraple- 7ber Rat 1953;33:575-581, 621-629.

6 Milinsky A. The prenatal diagnosis of neural gic children, J Bone Joint Swg [An.]. 1953; 46 Daniels L, Worthingham C. Muscle Testing:

tube and other congenital defects. In: Milinsky 35:220-226. Techniques of Manual Examination. 4th ed.

A, ed. Genetic Disorders and h e Few: Diag- 26 Lock TR,Aronson DD. Fractures in patients Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1980.

nosis, Pm~ention,and Treatment. New York, who have myelomeningocele. J Bone Joint

NY: Plenum Publishing Corp; 1986:453-519. 47 Stuberg WA, Metcalf WK. Reliability of

Swg [Am]. 1989;71:1153-1157. quantitative muscle testing in healthy children

7 McLone: DG. Treatment of myelomeningo- 27 Samuelsson L, Eklof 0 . Hip instability in and in children with Duchenne muscular dys-

cele: arguments against selection. Clin Neuro- myelomeningocele: 158 patients followed for trophy using a hand-held dynamometer. Phys

surg. 1986;3:359-370. 15 years. Acta Orthop Scand 1990;61:3-6. mer. 1988;68:977982.

8 Lorber J. Results of treatment of myelomen- 28 Abraham E, Verinder DG, Sharrad WJ.The 48 Fiorentino MR. Reflex Testing Merhocisfor

ingocele. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1971;13: treatment of flexion contracture of the knee in Evaluating Central Navom System Develop-

2P303. myelomeningocele. J Bone Joint Swg [Br]. ment 2nd ed. Springfield, 111: Charles C Tho-

9 Gross RH, Cox A, Tatyrek R, et al. Early 1977;59:433-438. mas, Publisher; 1981.

management and decision making for the 29 Bauer SB. Urologic management of the 49 Barnes MR, Crutchfield CA, Heriza CB,

treatment of myelomeningocele. Pediatrics. myelodysplastic child. ProbIems in Urology. Herdman SJ. ReJa and Vestibularhpsects of

1983;72:45@458. 1989;3:86-101. Motor Control, Motor Development, and Mo-

10 McLaughlin JF, Shunleff DB, Lamers JY, et 30 Bauer SB, Hallet M, Khoshbin S, et al. Pre- tor Lemning. Morgantown, W. Stokesville

al. Influence of prognosis on decisions regard- dictive value of urodynamic evaluation in new- Publishing Co; 1990.

ing the care of newborns with myelodysplasia. borns with myelodybplasia.JAMA. 1984; 50 Wolf LS, McLaughlin JFJ. Early motor devel-

N Engl J /Wed. 1985;312:1589-1594. 252:650-652. opment of children with myelomeningocele.

11 Banta JV, Lin R, Peterson M, Dagenais T. 31 Evans K, Hickman V, Carter CO. Handicap Presented at the annual meeting of the Ameri-

The team approach in the care of the child and social status of adults with spina bifida can Academy of Cerebral Palsy and Develop-

with myeY omeningocele. Journal of Prosthetics cystica. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1974;28:8592. mental Medicine; October 1984; Washington,

and Orthotics. 1989;2:263-273. DC.

32 Whitehead WE, Parker LH,Bosmajian L, et

12 Chauvel P. Spina bifida and hydrocephalus. al. Treatment of fecal incontinence in children 51 Sousa JC, Telzrow RW, Holm RA, et al. De-

In: Capute AJ, Accardo PJ, eds. Developmental with spinal bifida: comparison of biofeedback velopmental guidelines for children with my-

Dkabilities in infancy and Chilahod. Balti- and behavior modification. Arch Phys Med Re- elodysplasia. Phys Ther. 1983;63:21-29.

more, Md: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co; habil. 1986;17:218-224, 52 Shurtleff DB. Myelodysplasia: management

1991:383--393. and treatment. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1980;

33 Mazur JM, Aylward GP, Colliver J, et al. Im-

13 Stark GD, Drummond MB, Poneprasert S, paired mental capabilities and hand function 10:798.

Robarts FH. Primary ventriculoperitoneal in myelomeningocele patients. Z Kinderchir. 53 Folio MR, Fewell RR.Peabody Dalelop-

shunts in treatment of hydrocephalus associ- 1988;43(suppl 2):24-27. mental Motor Scales and Actitrify Cards Man-

ated with myelomeningocele. Arch Dis Child. ual. Hingham, Mass: DLM Teaching Resources;

1974;9:112-117. 34 Mazur JM, Menelaus MB, Hudson I, Still-

well k Hand function in patients with spina 1983.

14 Soare PL, Raimondi 4. Intellectual and bifida cystica.J Pedratr m o p . 1986;6:442-447. 54 Bayley N. BayIey Scales of infant Daelop-

perceptua-motor characteristics of treated my- ment. New York, NY: The Psychological Corp;

elomeningocele children. Am J Dis Child. 35 Strecker WB, Riordan MT, Daily L. Hand

grasp measurements in myelomeningocele 1969.

1977;131:19+204.

patients. Presented at the annual meeting of 55 Knobloch H, Stevens F, Malone A. A Man-

15 Miller E, Sethi L. The effect of hydrocepha- the American Academy of Orthopedic Sur- ual of Dawlcpnental Diagnais: The Adminis-

lus on perception. Dev Med Child Neurol. geons; February 8-15, 1 9 0 ; New Orleans, La. tration and Interpretation of the Raked Gesell

1971;13(suppl 25):77-81. and Am- Dewlopmental and Neurologi-

36 Wallace SJ. The effect of upper-limb func-

16 Mapsstone TB,Rekate HL, Nulsen FE, et al. tion on mobility of children with myelomenin- cal Examination. New York, NY: Harper &

Relationship of CNS shunting and 1Q in chil- gocele. Da) Med Child Neurol. 1973;15(suppl Row, Publishers Inc; 1980.

dren witti myelomeningocele. Child's Brain. 29):8491. 56 Hoffer MM, Feiwell E, Perry R, et al. Func-

1984;11:112-118. tional ambulation in patients with myelomen-

37 Joint Motion: Method of Measuring and

17 Schut L, Bruce DA The Arnold-Chiari mal- Recording. Park Ridge, Ill: American Academy ingocele. J BoneJoint Swg [Am]. 1973;

formation. Orrhop Clin North Am. 1978; of Orthopedic Surgeons; 1965. 55:137-148.

9:913923. 57 Drummond DS, Moreau M, Cruess RL.

38 Moore ML. The measurement of joint mo-

18 Raynor RB. The Arnold-Chiari malforma- tion, pan 11: the technic of goniometry. Phys Post-operative neuropathic fractures in patients

tion. Spine. 1986;11:343-344. T k r Rev. 1949;29:256-264. with myelomeningocele. Da) Med Child Neu-

19 Park 'TS, Hoffman HJ,Hendrick EB, Hum- 39 Forero N, Okamura L, Larson M. Normal rol. 1981;23:147-150.

phrey~RP. Experience with surgical decom- ranges of hip motion in neonates. J P e d a 58 Samuelsson I., Skoog M. Ambulation in

pression of the Amold-Chiari malformation in W o p . 1989;9:391-395. patients with myelomeningocele: a multivariate

young infants with myelomeningocele. Neuro- statistical analysis. Pedian-ic Orthopedics.

surgery. 1983;13:147-152. 40 McDonald C, Jaffe K, Shurtleff DB. Assess-

ment of muscle strength in children with men- 1988;8:569-575.

ingomyelocele: accuracy and stability of mea- 59 Dudgeon BJ, Jaffe KM,Shurtleff DB. Varia-

tions in midlumbar myelomeningocele: impli-

Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number

cations for ambulation. Pediatric Physical Ther- 69 GugenheimJ, Rosenthal RK, Dabrowski S, early use of a wheelchair. J Bone Joint Surg

apy. 1991;3:57-62. Hall JE. Adduaor transfer in the higt-risk hip in [Br]. 1989;71:56-61,

60 Carroll NC. Assessment and management myelodysplasia. Clin Onhp. 1978;132:10&114. 78 McMaster M. The long-term results of

of the lower extremity in myelodysplasia. Or- 70 Thomas L1, Thompson TC, Strub LR. Trans- kyphectomy and spinal stabilization in chil-

thop Clin North Am. 1987;18:709724 plantation of the external oblique muscle for dren with myelomeningocele. Spine.

61 Lee EH, Carroll NC. Hip stability and am- abductor paralysis.J Hone Joinl Surg [Am]. 1988;13:417-424.

bulatory status in mye1omeningocele.J Pediafr 1950;32:207-217. 79 Lord J, Varzos N, Behrman B, et al. Impli-

Orlhop. 1985;5:522-527. 71 Sharrard WJW. Posterior iliopsoas trans- cation of mainstream classrooms for adoles-

62 Molloy MK. The unstable paralytic hip: plantation in the treatment of paralytic disloca- cents with spina bifida. Deu Med Child Neural.

treatment by combined pelvic and femoral tion of the hip. J Bone Joini S q [Rr] 1990;32:2&29.

osteotomy and transiliac pso* transfer. J Pedi- 1964;46:426444. 80 Ward WT, Wenger DK, Roach JW. Surgical

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/71/12/935/2728739 by The University of Texas at El Paso user on 28 October 2018

ntr Orrhop. 1986;6:533-538. 72 Rosenstein BD, Greene WB, Herringon RT, correction of myelomeningocele scoliosis: a

63 Stillwell A, Menelsus MB. Walking ability Blum AS. Bone density in myelomeningocele: critical appraisal of various spinal instrumenta-

after transplantation of the iliopsoas: a long- the effects of ambulatory status and other factors. tion systems. J Pedia& Orthop. 1989;9262-268.

term follow-up.]Bone Joint Surg [BY/. Derl Med Child Naml. 1987,29486494, 81 Mazur JM, Menelaus MB, Dickens DR, Doig

1984;66:656659, 73 Lindseth RE,Glancy J. Polypropylene lower WG. Efficacy of surgical management for scoli-

64 Bunch WH, Hakala MW. lliopsoas transfers extremity braces for paraplegia due to my- osis in myelomeningocele: correction of defor-

in children with myelomeningocele. J Bone elomeningocele.J Bone Joint Surg [Am/. miry and alteration of functional status. J Pedi-

Joint Surg [Am]. 1984;66:224-227 1974;56:556-563. a n Orthop. 1986;6:568-575.

65 Crandall KC, Hirkebak RC, Winter RB. The 74 McCall RE, Schmidt W. Clinical experi- 82 Findley W ,&re JC, Hirkebak RC, et al.

role of hip location and dislocation in the ence with the reciprocal gait orthosis in my- Ambulation in adolescent with myelomeningo-

functional status of the myelodysplastic patient: elodysplasia.J Pedialr Orthop. 1986;6:157-161. cele, I: early childhood predictors. Arch PLys

a review of 100 patienu. Orthopedics. 1989; 75 Flandty F, Burke S, Robem J, et al. Func- Med Rehabil 1987;68:518-522.

12:675-684. tional ambulation in myelodysplasia: the effect 83 Agre JC, Findley TW,McNally MC, et al. Phys-

66 Sherk HH, Melchionne J, Smith R. The nat- of orthotic selection on physical and physio- ical activity in children with myelomeningocele.

ural history of hip dislocations in ambulatory logic performance. J Pediafr Orhop. 1986; Arch Pbp ,Wed Rehabil 1987;68:372-377.

myelomeningoceles. Z Kinderchir. 1987; 6:661-665. 84 Harris M, Banta J. Cost of skin care in the

42(suppl 1 ):48-49. 76 Logan L, Ryers-Hinkley K, Ciccone CD. Ante- myelomeningocele population. J Pediatr Or-

67 Riggins KS, Kraus J, Fontanetts P. Hip dislo- rior vs pt~steriorwalkers: a gait analysis study. thop. 1990;10:355-361.

cations in myelodysplasia: a hnctional assess- Uec)Med C?&JNavoI. 199032:1044-1048. 85 Castree B, Walker TH. The young adult with

ment. South Med ]. 1983;76:736-739. 77 Mazur JM, Shurtleff DB, Menelaus MR, Col- spina bifida. Br Med J. 1981;283:1040-1042.

68 I3azih J, Gross RH. Hip surgery in the lum- liver J. Orthopaedic management of high-level 86 McLone DG. Spina bifida today: problems

bar level myelomeningocele patient. J Pedian spina bifida: early walking compared with adults face. Semin NmoC 1989;9:16+175.

Orthop. 1981;1:405-411.

. THREE WAYS

Movemen# Science .. ..... T O ORDER

.V :

... APTA ,,

,,

Now available a s a monograph from ~ b luls a t 800/999-2782, ext

31 only,

o r 703/684-2782. ext 31 14.

,,,, ,

9:00 AM t o 5:00 PM, EST, to'

The multidisciplinary field of movement science has important implications

.

your credit cord order

for curriculum development and clinical practice in physical therapy. using y o u r VISA o r

MasterCard.

The 23 articles making up this monograph-originally published in Physical

.

Therapy in 1990 and 1991-reflect the diversity of topics within this broad

behavibrial domain and underscore the need for inte;disciplinary

6 v mail:

&il a letter (specify Order

No. P-81) with your check,

interactions.

Articles focus on . payable t o APTA, to:

office Services

American Physical Therapy

Disorders of movement control,

Issues in motor learning, and .. Association

1 11 1 North Fairfax Street

Developmental and pediatric concerns.

.

Alexandria, VA 2231 4-1 488

I Clinician, researcher, educator, student-if you're a "student"of human BY FAX: I

1 . I

I movement behavior,. vou're certain to find Movement Science an essential

addition to your professional library

S i n d a letter (specify Order

No. P-81) t o 703/684-7343,

f o r VISA a n d M a s t e r c a r d I

Guest edited by Winstein and Knecht, with 33 contributors. orders (minimum of $1 0.00) o r

p u r c h a s e o r d e r s (over $20.00)

(23 articles, 246 pages, 1 99 1 )

only. O u r fax line is o p e n 24

Make your move now-order Movement Science today! hours. Letters confirming faxes

o r e n o t necessary. OA1B1

78 1946 Physical TherapyNolume 71, Number 12December 1991

You might also like

- Cerebral Palsy: Christian M. Niedzwecki, Sruthi P. Thomas, and Aloysia L. SchwabeDocument23 pagesCerebral Palsy: Christian M. Niedzwecki, Sruthi P. Thomas, and Aloysia L. SchwabeSergio Navarrete VidalNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy: Neil Wimalasundera, Valerie L StevensonDocument12 pagesCerebral Palsy: Neil Wimalasundera, Valerie L StevensonMATERIAL24No ratings yet

- MedBack MyelomeningoceleDocument3 pagesMedBack MyelomeningoceleJulia Rei Eroles IlaganNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic BladderDocument8 pagesNeurogenic BladderrafendyfendyNo ratings yet

- Espina Bifida 2022Document7 pagesEspina Bifida 2022Edwin Fabian Paz UrbanoNo ratings yet

- Neural Tube Defects: Group 1Document28 pagesNeural Tube Defects: Group 1imneverwrong2492100% (1)

- SpinaBifida ManagementDocument4 pagesSpinaBifida ManagementDimple GoyalNo ratings yet

- Caringforthechildwith Spinabifida: Brandon G. Rocque,, Betsy D. Hopson,, Jeffrey P. BlountDocument13 pagesCaringforthechildwith Spinabifida: Brandon G. Rocque,, Betsy D. Hopson,, Jeffrey P. Blountyoussef alaouiNo ratings yet

- Bahan Ajar Iv Spina BifidaDocument7 pagesBahan Ajar Iv Spina Bifidaanon_800290919No ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument7 pages1 PBsahrirNo ratings yet

- Pediatric RehabDocument32 pagesPediatric RehabRainy DaysNo ratings yet

- Spina BifidaDocument33 pagesSpina BifidaRegine Prongoso DagumanpanNo ratings yet

- Spinal DysraphismDocument2 pagesSpinal DysraphismkhadzxNo ratings yet

- MeningomyeloceleDocument34 pagesMeningomyelocelerajan kumarNo ratings yet

- BlepharoptosisDocument7 pagesBlepharoptosissariNo ratings yet

- Graham 2016Document25 pagesGraham 2016Constanzza Arellano LeivaNo ratings yet

- Fetal Ventriculomegaly: Postnatal Management: Special Annual IssueDocument3 pagesFetal Ventriculomegaly: Postnatal Management: Special Annual IssueRendra Artha Ida BagusNo ratings yet

- DiscursoDocument21 pagesDiscursoLeslye SimbañaNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 518Document5 pagesTutorial 518corinna.ongaigui.gsbmNo ratings yet

- MC Allister JPPathophysiologyofcongenitalandneonatalhydrocephalus Sem Fetal Neonat Med 2012Document11 pagesMC Allister JPPathophysiologyofcongenitalandneonatalhydrocephalus Sem Fetal Neonat Med 2012nendaayuwandariNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Encephaloceles A Case SeriesDocument4 pagesPattern of Encephaloceles A Case SeriesSayyid Hakam PerkasaNo ratings yet

- 10.7556 Jaoa.2015.022Document5 pages10.7556 Jaoa.2015.022CarolinaNo ratings yet

- Myelomeningocele - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument13 pagesMyelomeningocele - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfEmmanuel Andrew Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- No. 44. Neural Tube DefectsDocument11 pagesNo. 44. Neural Tube DefectsenriqueNo ratings yet

- Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine: N. Scott AdzickDocument6 pagesSeminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine: N. Scott AdzickTatiana Benito RojasNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00381 020 04746 9Document12 pages10.1007@s00381 020 04746 9Alvaro Perez HenriquezNo ratings yet

- Neural Tube Defects: Dr.M.G.Kartheeka Fellow in Neonatology Cloudnine, OARDocument36 pagesNeural Tube Defects: Dr.M.G.Kartheeka Fellow in Neonatology Cloudnine, OARM G KARTHEEKANo ratings yet

- Medscape Spina BifidaDocument25 pagesMedscape Spina Bifidarica dhamayantiNo ratings yet

- TCRM 12 1271 PDFDocument6 pagesTCRM 12 1271 PDFAnindya M ChoirunnisyaNo ratings yet

- 2011 32 109 Holly A. Zywicke and Curtis J. Rozzelle: Pediatrics in ReviewDocument10 pages2011 32 109 Holly A. Zywicke and Curtis J. Rozzelle: Pediatrics in ReviewNavine NalechamiNo ratings yet

- (Sici) 1098 2779 (2000) 6:1 1::aid mrdd1 3.0.co 2 JDocument5 pages(Sici) 1098 2779 (2000) 6:1 1::aid mrdd1 3.0.co 2 JANDREA QUIROZ ARCILANo ratings yet

- Craniofacial Syndromes.33Document26 pagesCraniofacial Syndromes.33andrew kilshawNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Diagnosis ofDocument6 pagesAntenatal Diagnosis ofnskhldNo ratings yet

- Torticollis, Facial Asymmetry and Plagiocephaly in Normal NewbornsDocument6 pagesTorticollis, Facial Asymmetry and Plagiocephaly in Normal NewbornsJuan Pablo PérezNo ratings yet

- Espina BífidaDocument18 pagesEspina BífidaDamary Cifuentes ReyesNo ratings yet

- Case GfndyDocument9 pagesCase Gfndyednom12No ratings yet

- Spina BifidaDocument11 pagesSpina BifidaheiyuNo ratings yet

- Spinal DisDocument32 pagesSpinal DisAkmal Niam FirdausiNo ratings yet

- Spen 2002 32505Document10 pagesSpen 2002 32505tuanguNo ratings yet

- Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy: An Overview of Early Treatment ConsiderationsDocument7 pagesBrachial Plexus Birth Palsy: An Overview of Early Treatment Considerationsphannghia.ydsNo ratings yet

- Clinical Ophthalmology: Clinical Presentation and Management of Congenital PtosisDocument25 pagesClinical Ophthalmology: Clinical Presentation and Management of Congenital PtosisEnjelinmariesca KaruriNo ratings yet

- Back Et Al-2014-Annals of NeurologyDocument18 pagesBack Et Al-2014-Annals of NeurologyBere GuzmánNo ratings yet

- Spina BifidaDocument29 pagesSpina Bifidaann dimcoNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Posterior Plagiocephaly: ObjectiveDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Posterior Plagiocephaly: ObjectiveSelene MéndezNo ratings yet

- Antibody Mediated Autoimmune Encephalitis in ChildhoodDocument11 pagesAntibody Mediated Autoimmune Encephalitis in ChildhoodTessa CruzNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument14 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptMeirani RizdaputriNo ratings yet

- Prenatal Ischemia Deteriorates White Matter, Brain Organization, and FunctionDocument10 pagesPrenatal Ischemia Deteriorates White Matter, Brain Organization, and FunctionJakssuel AlvesNo ratings yet

- Spina Bifida General Dental PracticeDocument5 pagesSpina Bifida General Dental PracticerambuanggieNo ratings yet

- Craniofacial Encephalocele: Updates On Management: Amelia Alberts, Brandon Lucke-WoldDocument13 pagesCraniofacial Encephalocele: Updates On Management: Amelia Alberts, Brandon Lucke-Woldhidayat adi putraNo ratings yet

- Basic NewerDocument9 pagesBasic Newerblack smithNo ratings yet

- Positional Plagiocephaly Evaluati - 2004 - Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery CliniDocument8 pagesPositional Plagiocephaly Evaluati - 2004 - Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinilaljadeff12No ratings yet

- J Child Neurol 2001 Fennell 58 63Document6 pagesJ Child Neurol 2001 Fennell 58 63Elena GatoslocosNo ratings yet

- Selima 2020Document9 pagesSelima 2020Ginecología CMMNo ratings yet

- OMT Per Gestire Le Condizioni OftalmicheDocument8 pagesOMT Per Gestire Le Condizioni OftalmicheEleonora FiocchiNo ratings yet

- Difficult Questions Facing The CR 2004 Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery ClinicDocument10 pagesDifficult Questions Facing The CR 2004 Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Cliniclaljadeff12No ratings yet

- Neural Tube DefectDocument8 pagesNeural Tube DefectReema Akberali nooraniNo ratings yet

- Impact of Cerebral Palsy Outline: A Research Review: Sharath Hullumani VDocument5 pagesImpact of Cerebral Palsy Outline: A Research Review: Sharath Hullumani VSharath Hullumani VNo ratings yet

- Classification, Diagnosis, and Etiology of Craniofacial DeformitiesDocument32 pagesClassification, Diagnosis, and Etiology of Craniofacial DeformitiesCarolina Orozco NavarroNo ratings yet

- Operative Brachial Plexus Surgery: Clinical Evaluation and Management StrategiesFrom EverandOperative Brachial Plexus Surgery: Clinical Evaluation and Management StrategiesAlexander Y. ShinNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Disorders in Children: A Multidisciplinary Approach to ManagementFrom EverandNeuromuscular Disorders in Children: A Multidisciplinary Approach to ManagementNicolas DeconinckNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Current Asset - Cash & Cash Equivalents CompositionsDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Current Asset - Cash & Cash Equivalents CompositionsKim TanNo ratings yet

- Field Study 1-Act 5.1Document5 pagesField Study 1-Act 5.1Mariya QuedzNo ratings yet

- Flaxseed Paper PublishedDocument4 pagesFlaxseed Paper PublishedValentina GarzonNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument1 pageDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesAre Em GeeNo ratings yet

- BRSM Form 009 - QMS MDD TPDDocument15 pagesBRSM Form 009 - QMS MDD TPDAnonymous q8lh3fldWMNo ratings yet

- Tests Conducted On Under Water Battery - YaduDocument15 pagesTests Conducted On Under Water Battery - YadushuklahouseNo ratings yet

- TDS-PE-102-UB5502H (Provisional) 2019Document2 pagesTDS-PE-102-UB5502H (Provisional) 2019Oktaviandri SaputraNo ratings yet

- D435L09 Dental Trauma-2C Cracked Teeth - 26 Root FractureDocument73 pagesD435L09 Dental Trauma-2C Cracked Teeth - 26 Root FractureD YasIr MussaNo ratings yet

- Maintenance Service Procedure Document For AMC: Scada &telecom System For Agcl Gas Pipeline NetworkDocument17 pagesMaintenance Service Procedure Document For AMC: Scada &telecom System For Agcl Gas Pipeline NetworkanupamNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument8 pagesUntitledapi-86749355No ratings yet

- Cvmmethod 101220131950 Phpapp02Document20 pagesCvmmethod 101220131950 Phpapp02AlibabaNo ratings yet

- TAXATIONDocument18 pagesTAXATIONNadine LumanogNo ratings yet

- Sail ProjectDocument28 pagesSail ProjectShahbaz AlamNo ratings yet

- TruEarth Case SolutionDocument6 pagesTruEarth Case SolutionUtkristSrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Civil Aviation Authority of BangladeshDocument1 pageCivil Aviation Authority of BangladeshS.M BadruzzamanNo ratings yet

- Using Oxidation States To Describe Redox Changes in A Given Reaction EquationDocument22 pagesUsing Oxidation States To Describe Redox Changes in A Given Reaction EquationkushanNo ratings yet

- Kidney Diet DelightsDocument20 pagesKidney Diet DelightsArturo Treviño MedinaNo ratings yet

- Jepretan Layar 2022-11-30 Pada 11.29.09Document1 pageJepretan Layar 2022-11-30 Pada 11.29.09Muhamad yasinNo ratings yet

- ASTM Standards For WoodDocument7 pagesASTM Standards For WoodarslanengNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 - Elements of Plasticity TheoryDocument13 pagesLecture 5 - Elements of Plasticity TheoryNeeraj KumarNo ratings yet

- Vertico SynchroDocument16 pagesVertico SynchrozpramasterNo ratings yet

- DexaDocument36 pagesDexaVioleta Naghiu100% (1)