Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Of Viz.:: Inhabitants of Mountain Sulu Tribes, T H e Who The

Of Viz.:: Inhabitants of Mountain Sulu Tribes, T H e Who The

Uploaded by

Chessy Moreno0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views9 pagesOriginal Title

phil.lit

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views9 pagesOf Viz.:: Inhabitants of Mountain Sulu Tribes, T H e Who The

Of Viz.:: Inhabitants of Mountain Sulu Tribes, T H e Who The

Uploaded by

Chessy MorenoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

PHIL1 P P I N E LITERATURE

BY FRANK’R. BLAKE

T H E native population of the Philippine Islands is made up of

a number of different tribes, which fall naturally into three

groups, viz.:

u. The mountain pagan tribes, including the dwarf-like Negritos,

doubtless the aboriginal inhabitants of the archipelago.

b. The Mohammedan Moros of Sulu and Mindanao.

c. The Christian tribes, the Indios or Filipinos of the Spaniards, who

form the bulk of the population.

All these tribes, with the possible exception of the Negritos,

speak languages which belong to the same linguistic family, the Ma-

layo-Polynesian or Indonesian, embracing the languages spoken on

almost all of the islands of the Pacific, on the Malay peninsula, and

on the distant island of Madagascar. Every tribe, however, in

each of these different groups, has its own language, distinct from

those of its neighbors.

These languages have produced little or nothing which can

claim to be literature in the sense of elegant and artistic writing.

The literature of the Philippine languages is literature only in the

broader sense of written speech, and it is in this sense that the term

“Philippine Literature” is used in the present paper.

Few of the languages of the pagan tribes exist at all in written

form. The Tagb6nwas of Palawan, the long, narrow island stretch-

ing from Borneo towards Ixzon, and their northern neighbors, the

Mangyans of Mindoro, possess native alphabets, but these are

probably not employed except for short inscriptions.’ All other

works in the languages of this group are printed in Roman type and

are practically all of a religious character, being written by various

1 Cf. A. B. Meyer; A. Schadenberg; and W. Foy, Die Mangianschrifl von Min-

doro. Berlin, 1895; F. Blumentritt, Die Mangienschrift uon Mindoro. Braunschweig.

1896.

449

450 AMERICAN A NTHROPOLOCIST [N. S., X3, I911

missionaries for the conversion and religious edification of different

pagan tribes. Only five languages possess any written monuments,

and none of these more than one or two specimens. Of special

interest is the work of a member of the Tiruray tribe of Mindanao

in Spanish and Tiruray, on the customs of his fellow-tribesmen.'

The two principal languages of the Mohammedan tribes or

Moros are Sulu, which is spoken mainly in the domains of the Sultan

of Sulu on the chain of small islands extending from Mindanao to

Borneo, and Magindanaw, the speech of the most powerful tribe

on the large island of Mindanao.

The Moros* are unacquainted with the art of printing, their

literary monuments being all in manuscript form, written in a

slightly modified variety of the Arabic alphabet, similar to that

used by the Malays of the Malay peninsula.

Their writings may be classified under four heads:

a. Historical annals, more or less legendary, consisting prin-

cipally of genealogies of the datos or Moro chiefs.

b. Legal codes, based on various collections of Arabic law.

c. Religious texts, translations of the Kuran and its commeii-

taries, of the Hadith or traditions regarding Mohammed, orations

for the different Mohammedan festivals, etc.

d . Writings of varied character, stories, magic-texts, letters of

the different datos, etc.

Almost all Moro manuscripts begin, just as most Arabic books

do, with the Arabic phrase bismi 'ZZdhi 'rrahmdni ' r ~ a h h i "in

, the

name of God,the Compassionate, the Merciful." This is usually

followed by a sentence or two in Malay. The Moros derive their

learning from Arabic and Malay sources, and consequently take

pride in airing their Arabic and Malay erudition.

Practically all Moro books are thus written by the Moros them-

selves. There is but one work, so far as I know, in a Moro language

written by a foreigner, a printed catechism of Christian doctrine

in Spanish and Magindanaw by a Jesuit missionary.

_.

1 J.

Tenorio (a Sigayftn), Cosfumbrcs de los indios tirurayes, Manila, 1892 (two

columns, Spanish and Tiruray).

2 Cf. N. M. Saleehy, Studies in M o m History. Law, Religion, Ethnol. Survey

Pubs.. Dept. of Interior. vol. IV, part I. Manila. 1905.

BLAKE] PHILIPPINE LITERATURE 451

The Christian tribes constitute by far the most important

element of the native population, both on account of their numbers

and the comparatively high degree of civilization to which they have

attained. The various tribes, while speaking distinct languages,

have practically the same characteristics and customs, and really

form one people.

At the time of the Spanish discovery and conquest, in the 16th

century, the now Christianized Filipinos possessed native alphabets

similar to those still used by the Tagbbnwas of Palawan, and the

Mangyans of Mindoro. There are notices of native Mss. in at

least one Spanish writer,' but none of these have been preserved

to our day, all existing works dating from the Spanish period.

Moreover, even the ancient alphabets have been forgotten. All

Philippine books with, so far as I know, but one exception, being

printed in Roman type. This unique work, published in 1621,

is an Ilokan catechism printed in Tagalog characters by the Austin

friar Francisco Lopez.

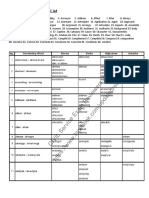

The number of works published in the various languages of the

Christian tribes down to 1903,according to the best bibliographies,

1898and 1903respectively,2 is approximately as follows. Bisayan

and Tagalog stand first with something under 300 works each. The

next in rank, Ilokan, has less than half that number. Then.follow,

in a descending scale, Bikol with about 60, Pangasinan about 30,

Pampanga 19, Ibanag 12,Kuyo 6, Zambal3, Batan and Kalamian

I each. In all there are about 800 works in the eleven languages

here mentioned.

These books are of all sizes varying from small pamphlets of

nine or ten pages to quarto volumes of six and seven hundred.

The numbers here given, especially in the case of Tagalog and

Bisayan, have probably been considerably augmented in the last

few years3

~-

1 Cf. Report of Philippine Commission. ~ g o o 1x1,

, p. 403.

2W. E. Retana, Catdlogo abreviado de la biblioieca filipina, Madrid, 1898; T. H.

Pardo de Tavera, Biblioleca Filipina, Washington, 1903.

8 In Retana's latest bibliography, Aparato biblwgr6Jica de la historia general de

Filipinas, 3 vols., Madrid, 1906, the only works in the native languages listed from

1903 to 1905 (about a s ) are in Tagalog.

452 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N. s., 13, 1911

The works written in these various languages are composed in

both prose and verse, the verse being apparently of native origin.

Tagalog verse,’ which may serve as an example, consists of lines

containing the same number of syllables, and the ends of the lines

in the same stanza must be in assonance with each other according

to certain definite principles. The final syllables of all the lines

of a stanza must have the same vowel, whether this vowel is final

or is followed by a consonant. Of words ending in a consonant,

there are two classes, those ending in p , b, t , d, R , g, s, and those

ending in 1, m,n, ng, y, w . Any word of one class may be used in

assonance with any other word of that class, provided the vowel

is the same, but words of the two classes can not be used together

in the same stanza. For example bond& ‘mountain,’ ending in i:,

may be used in assonance with l60b ‘heart,’ ending in b, and mahdl

‘noble’ ending in E with bildng ‘number,’ ending in the guttural

nasal ng. I t is to be noted that the words of the first class end

in stop sounds or the spirant s, i. e., in noised sounds, sounds ac-

companied by considerable friction of the escaping air, while the

words of the second class all end in what are known as sonorous

sounds, sounds made with little audible friction, and are charac-

terized by greater resonance of the speech organs. Words with

final vowel also fall into two classes, those with simple vowel, e. g . ,

ldwo ‘man,’ and those with so-called guttural vowel, i. e., a vowel

followed by the glottal catch, e. g . , wald ‘not having.’ Words of

one of these classes can not be used in assonance with those of the

other, nor can a word ending in either kind of vowel stand in as-

sonance with a word having a final consonant. The difference

between these two classes of vocalic endings is also apparently a

difference in sonorousness, a simple vowel being more sonorous

than one foliowed by the glottal catch. The principal Tagalog

meters consist of seven, eight, twelve, or fourteen syllables to a

verse, and three, four, five, or eight verses to a stanza.

The great majority of the works written in the languages of

this group, at least five-sixths, are of a religious character, written

__

‘Cf. W.G. Seiple, Tagdlog Podry, JHU Circs., Vol. XXII. No. 163, June, 1903

pp. 78-79.

BLAKE]

PHILIPPINE LITERATURE 453

by the friars of the various orders for the instruction and dification

of their flocks, for in the Philippine Islands under the Spanish

regime, the friars had become the occupants of practically all the

parishes in the archipelago to the exclusion of the native secular

priests. This was one of the chief causes of the antagonism of the

people towards the religious orders. Many of these religious works

are simply translations from the Spanish. All the works in Kuyo,

Zambal, Calamian, and Batan are religious, and in all the other

languages except Tagalog books of a secular character are very

rare: for example Bisayan and Ilokan which rank next to Tagalog

in this respect have about a dozen each. These religious works

consist of catechisms and manuals of Christian doctrine, books on

deportment, lives of the saints, collections of sermons, novenas or

series of nine days prayer to some saint, etc., the novenas being by

far the most numerous.

The class of writings which stands next to the religious works

in point of view of numbers, is the poetical romance or corrido, the

latter term being a corruption of the Spanish ocurrido,l the passive

participle of the verb ocurrir ‘happen.’ These are practically con-

fined to Tagalog. They are remarkable tales of the adventures of

royal or noble personages, usually in some remote or imaginary

country, e. g., Pinagdadnang bdhay ni Don Josd Flores at nang

princesa Virginia nu andk nang hdring Magaloaes sa Kahariang

Turkia, “The life of Don JosC Flores and the princess Virginia,

daughter of king Magaloaes in the kingdom of Turkey”; or Corrido

at bzihay nu pznagdadnan nang principe Orontis at nang reinang

Talestr is sa kaharian nang Temisila, “The story and life of prince

Orontis and queen Talestris in the kingdom of Temisita.”

The corrido entitled Pinagdadnang bdhay in Florante at ni

Laura sa Kahardang Albania, “Life of Florante and Laura in the

kingdom of Albania,” written in 1870 by Francisco Baltazar, a

native of the former province of Laguna near Manila, is considered

the best poem in Tagalog. I t opens in the following style:

1 The Spanish word, however, never means romance or tale.

454 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N.s., 13, 19rr

I) Sa isbng madillrn ghbat na mapanilbo

dawhg na matinlkay walhng pagltan

hblos naghihlrap ang kay Febong sllang

dumhlao sa Mob na lubhlng mashkal

2) Malalaklng kfihoy ang inihahandbg

phwang dalamhhti, kahaplsa’t longk6t

hirni pa nang Lbon a y nakalulhnos

sa lhlong matirnpl’t nagsasayhng 16ob

3) Tanhng manth bhging na namimillpit

sa sang8 nang khhoy a y bPlot nang tinlk

may bhlo ang bhnia’t nagbibighy saklt

sa kanglno pa mang sumbgi’t rnalhpit.’

“There was a dark and lonely wood, choked with thorny bejtico,

into whose tangled interior the rays of the sun could scarcely pierce.

Tall trees presaged trouble, sadness and melancholy; the song of the

birds had a mournful sound even to the bravest and most joyous heart.

All the vines which wound about t h e branches of the trees were encased

in spines. Fruits hung rotting, threatening disease t o whoever ap-

proached.”

Dramatic productions, usually styled comedias, are found in

Tagalog, Bisayan, and Ilokan. Their favorite theme is a contest

for supremacy between some Christian and some Moro or Mohaln-

medan state, in which the Christians are always victorious. This

theme is a reflection of the long struggle which the Christian

Filipinos had with their turbulent Moro (Mohammedan) neighbors

on the south, .the Sulus and Magindanaos. From the end of the

16th century, when the Spaniards first came in contact with the

Moros, until the introduction of steam gun-boats about the middle

of the last century, these bold pirates harried the coasts of the

northern islands, just as in the Middle Ages the Northmen dcv-

astated the shores of Europe. For years neither property nor life

was safe, and hundreds were carried away into slavery. I t is but

natural that these times of storm and stress should have left a

lasting impression on the minds of the Filipinos, and that they should

attempt to get even with their Mohammedan foes, if only on paper.

After the American conquest a number of plays were produced

1 Notice the assonant eyllablee, 00 ( -ow), ow, ang. al, in the first stanza; og, OC

0s. ob, in the second; and it, ik. it. it, in the third.

BLAKE] PHILIPPINE LITERATURE 455

which were directed against the rule of the United States, the so-

called “Seditious Drama.” One of the best known of this class

of plays is Hind8 ak6 patdy, I ‘ I am not dead.”

The corrido and the drama are both without doubt borrowed

forms of literature, but not so the lyric poetry. Here we have, if

anywhere, the germs of a literature in the narrower sense. Much

of this poetry exists only in the mouths of the people, though some,

principally Tagalog, has been written down. Like the poetry of

Oriental peoples in general it is often difficult to understand. These

poems are mostly short and epigrammatic, consisting frequently of

but one stanza of three or four lines. The following will serve as

examples:

may lalBki masigyk,

gin60 kun tumugpb,

aitb kun s u m a l 6 n ~ a .

“There are some valiant men

Who are great lords when they embark,

But Negritos when they come to land

(i. e., they are h a v e until i t comes

to real fighting).”

pdsb ko’y lulutangldtang

sa gitnl nang kadagbtan

ang bking tinitimb6lang

tltig nang m a t l mo lbmang

‘ I M y heart swiys up and down like a float

In t h e midst of the sea,

The goal of my restless course

Is the gaze of thine eye alone.”

The Filipinos are very fond of proverbs and riddles which are

usually cast into poetic form. Many of their proverbs are bor-

rowed from Spanish, e. g.,

kahlma’t paramtbn ang hayop na m a k h h ,

magpakailbn ma’y makhln kun tawbgin.

“Though the monkey be clothed,

he will always be called a monkey.”

This is the Spanish : Azinque la mona se Vista dt! seda m o w se queda.

Many of the proverbs, however, are doubtless of native origin.

456 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST IN. S., 13, 1911

Examples of native riddles are:

Muntlng dagatdaghtan,

Binahbkod nang danglLy.

A little lake fringed with reeds [i.e., the eye].

Nang umPga’y tfkum pa

Nang mahhpo’y nabukh.

A t dawn its mouth is closed,

I n the evening it is open [i.e., a flower].

Newspapers and periodicals have been published in the three

principal languages, Tagalog, Bisayan, and Ilokan. These are

usually in two languages, a native dialect, and Spanish. Sometimes

they are printed in parallel columns, native dialect and Spanish

translation.

Portions of the New Testament, the Gospels and Acts of the

Apostles, have been translated into the principal languages, under

the auspices of the British and Foreign Bible Society. In all

probability a translation of the whole Bible is contemplated.

Books belonging to departments of literature other than the pre-

ceding are comparatively rare and are found principally in Tagalog.

There are grammars of Spanish in Tagalog, Bisayan, Ilokan, and

Ibanag. Medical works, usually of a practical character, and a

few legal treatises, are found in Tagalog and Bisayan.

Deserving of mention among the remaining works is a treatise

in Tagalog on the Filipino national sbort, the fighting of garne-

cocks, and the story si tunddng Basio Mukunat “The Cock Rasio

Macunat,” written by a Franciscan friar in i885 in order to instil

into the minds of the Filipinos the idea that it was best for them

not to learn Spanish or attempt to become civilized, that the more

ignorant a Filipino was, the happier he would be.

More than one third of all the works treated are anonymous, and

the authors of the rest are men of comparatively little note. While

many of these authors are Spaniards, a number are true native

Filipinos. Francisco Baltazar, the author of “ Florante and Laura,”

the best Tagalog poem, has already been mentioned. So far as I

know this is his only production. The most prolific of the writers

is one Mariano Perfecto, who composed about fifty different works

BLAKE] P H I L I P P I N E LITERATURE 457

in Bisayan on religious subjects. Next to him ranks Joaquin

Tuason, with twenty works in Tagalog, also of a religious character.

This brief sketch will serve to give,some idea of the extent and

character of works in the various Philippine languages. Whether

these languages or any one of them will ever develop a real literature,

is a question which only the future can answer.

Some persons, struck by the great resemblance which the various

Philippine languages bear to one another, have thought it would

be possible to fuse these languages into one, and form a sort of

national compound language, but such an artificial scheme is cer-

tainly impracticable. If the Filipinos are destined ever to have

a national language in which a national literature can be written,

that language will almost surely be Tagalog, the language of the

capital city, and of the most progressive race of the archipelago;

a language admirably suited by its richness of form and its great

flexibility for literary development, and needing but the master

hand of some great native writer to make it realize its latent possi-

bilities.

WINUSORHILLS,

BALTIMORE,MD.

A M . APiTW., N. 5 . . rg- 30

You might also like

- Grade 9 LM TLE Q1-Q4 PDFDocument325 pagesGrade 9 LM TLE Q1-Q4 PDFMay Ruselle71% (21)

- Poetry QuizDocument1 pagePoetry Quizkcafaro59No ratings yet

- 10 LM Foods Processing PDFDocument230 pages10 LM Foods Processing PDFMay Ruselle67% (18)

- Carolyn Evers - The Process of ChannelingDocument4 pagesCarolyn Evers - The Process of ChannelingGrace VersoniNo ratings yet

- Lorimar 2 EnglishDocument53 pagesLorimar 2 Englishmarclyn atiwag67% (3)

- Test of Reading Comprehension, Fourth Edition (TORC-4) : TORC-4 Has Five Subtests, All of Which Measure WordDocument4 pagesTest of Reading Comprehension, Fourth Edition (TORC-4) : TORC-4 Has Five Subtests, All of Which Measure WordFaye MartinezNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Diverse LearnersDocument9 pagesLesson Plan Diverse Learnersapi-250420087100% (1)

- COMPETENCY BASED LEARNING MATERIAL-Journalize-Trans.-enhancedDocument48 pagesCOMPETENCY BASED LEARNING MATERIAL-Journalize-Trans.-enhancedMay Ruselle100% (2)

- Carl Andre Sculpture Politics PDFDocument286 pagesCarl Andre Sculpture Politics PDFStefan PavalutaNo ratings yet

- Urbanism As A Way of Life by Louis WirthDocument1 pageUrbanism As A Way of Life by Louis WirthlaljoelNo ratings yet

- Brian BatesDocument4 pagesBrian BatesJuanita J. RinasNo ratings yet

- In Defence of The Roman LetterDocument21 pagesIn Defence of The Roman LetterGemma gladeNo ratings yet

- Syllabus ELE 501 Descriptive and Applied LinguisticsDocument3 pagesSyllabus ELE 501 Descriptive and Applied LinguisticsEL FuentesNo ratings yet

- Panulaang FilipinoDocument12 pagesPanulaang FilipinoJessica Malinao100% (1)

- Week 1 Learning ModuleDocument6 pagesWeek 1 Learning ModuleEllaine Kyle V. RiveraNo ratings yet

- Kahulugan at Kabuluhan NG Konseptong Pangwika Self Learning Worksheet in Komunikasyon at Pananaliksik Sa Wika at Kulturang Pilipino 11Document15 pagesKahulugan at Kabuluhan NG Konseptong Pangwika Self Learning Worksheet in Komunikasyon at Pananaliksik Sa Wika at Kulturang Pilipino 11Jushua Kurt Pilaspilas TaquebanNo ratings yet

- Literary Periods PH REVIEWER UPDATEDDocument4 pagesLiterary Periods PH REVIEWER UPDATEDabearaltheaNo ratings yet

- Language Competence Questionnaire 2023Document4 pagesLanguage Competence Questionnaire 2023Kristell Lyka LasmariasNo ratings yet

- The Medieval Concept of Spiritual, Intellectual, Political, and Economic Education. MonasticismDocument5 pagesThe Medieval Concept of Spiritual, Intellectual, Political, and Economic Education. MonasticismMyla Mendiola JubiloNo ratings yet

- Ang Paglinang NG KurikulumDocument21 pagesAng Paglinang NG KurikulumDesserie GaranNo ratings yet

- Antas at Barayti NG WikaDocument72 pagesAntas at Barayti NG WikaTop SavageNo ratings yet

- Francisco FDocument3 pagesFrancisco FErika May A. GuquibNo ratings yet

- Fill in The BlanksDocument1 pageFill in The BlanksBorn Campomanes LechugaNo ratings yet

- College of Teacher Education FIL 323 - Course Syllabus: 1. Course Number 2. Course NameDocument10 pagesCollege of Teacher Education FIL 323 - Course Syllabus: 1. Course Number 2. Course NameKRISTINE NICOLLE DANANo ratings yet

- Pananaliksik SilabusDocument5 pagesPananaliksik Silabusromeo pilongoNo ratings yet

- Proficiency Level On Applying Translation Skills AmongDocument18 pagesProficiency Level On Applying Translation Skills AmongYenna CayasaNo ratings yet

- Basic Features of Phil EssayDocument8 pagesBasic Features of Phil EssayVladimir B. Paraiso100% (1)

- Quiz Anapora at Katapora 25ptsDocument2 pagesQuiz Anapora at Katapora 25ptsAika Kristine L. ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document3 pagesChapter 1Karen MagsayoNo ratings yet

- Hindi by German V. GervacioDocument8 pagesHindi by German V. GervacioElijah Gabriel PerezNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency and Critical Thinking Skills of Filipino Maritime StudentsDocument9 pagesCognitive Academic Language Proficiency and Critical Thinking Skills of Filipino Maritime StudentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent ModuleDocument96 pagesChild and Adolescent ModuleDaryl Genelaso AlamanNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in Language and LiteratureDocument13 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in Language and LiteratureYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan-Week1-Filipino-AralpanDocument3 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan-Week1-Filipino-AralpanRodarbal Zerimar HtebNo ratings yet

- Odato PPT Grade 8 LessonDocument16 pagesOdato PPT Grade 8 LessonIvy OdatoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan FilipinoDocument61 pagesLesson Plan FilipinoMarielle Joy OrongNo ratings yet

- Ah MahDocument24 pagesAh MahNathalie Alba0% (1)

- Approaches and Strategies in Teaching PHDocument11 pagesApproaches and Strategies in Teaching PHJon Diesta (Traveler JonDiesta)No ratings yet

- Literary Devices FictionDocument20 pagesLiterary Devices FictionMary Grace CuizonNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature During American Regime: Three Groups of WritersDocument7 pagesPhilippine Literature During American Regime: Three Groups of WritersJEN100% (1)

- Antonio, Lilia F.: Lilia F. Antonio Was Born in Balara, Quezon City On 27 July 1949. She Is An EssayistDocument1 pageAntonio, Lilia F.: Lilia F. Antonio Was Born in Balara, Quezon City On 27 July 1949. She Is An EssayistJenelin EneroNo ratings yet

- Enrichment ActivitiesDocument4 pagesEnrichment ActivitiesjjNo ratings yet

- Mahayahay Is Grade 7 Performance TaskDocument3 pagesMahayahay Is Grade 7 Performance TaskCharity Anne Camille PenalozaNo ratings yet

- English 10 Module 11 LLMDocument6 pagesEnglish 10 Module 11 LLMrose ynqueNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Curriculum by George J. Posner 25-54Document31 pagesAnalyzing The Curriculum by George J. Posner 25-54ahlamNo ratings yet

- 4 Understanding Description TextsDocument9 pages4 Understanding Description TextsMicailah JariolNo ratings yet

- Types of LiteratureDocument3 pagesTypes of LiteratureCorinne ArtatezNo ratings yet

- DLL Nov 4, 2019 Ang WikaDocument6 pagesDLL Nov 4, 2019 Ang WikaJeppssy Marie Concepcion MaalaNo ratings yet

- Ang Alamat NG Bigas FILIPINODocument3 pagesAng Alamat NG Bigas FILIPINOMine CabuenasNo ratings yet

- Ikalawang Pagsasanay (PAGSASALIN)Document4 pagesIkalawang Pagsasanay (PAGSASALIN)Lemuel DeromolNo ratings yet

- Dimensions and Principles of Curriculum DesignDocument20 pagesDimensions and Principles of Curriculum DesignCARLO CORNEJONo ratings yet

- FL - Masining Na Pagpapahayag PDFDocument13 pagesFL - Masining Na Pagpapahayag PDFMa. Kristel OrbocNo ratings yet

- Balanghay: The Filipíno LanguageDocument4 pagesBalanghay: The Filipíno LanguageJoel Puruganan SaladinoNo ratings yet

- Parts of A Detailed Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesParts of A Detailed Lesson PlanEvichka SilverioNo ratings yet

- 1111Document2 pages1111イヴ・ アケル・ タヨNo ratings yet

- OBTL-Barayti at BaryasyonDocument8 pagesOBTL-Barayti at BaryasyonLaugene Faith Cahayagan AmoraNo ratings yet

- Lecture-Demo in Grade 8 English Lesson 1 - Enhancement & Consolidation Camp (Denn Marc P. Alayon)Document49 pagesLecture-Demo in Grade 8 English Lesson 1 - Enhancement & Consolidation Camp (Denn Marc P. Alayon)ZOSIMO PIZONNo ratings yet

- Q3 IptDocument41 pagesQ3 IptLIZMHER JANE SUAREZNo ratings yet

- Course Guide Filipino 7Document13 pagesCourse Guide Filipino 7Mycah Sasaki VlogNo ratings yet

- Grade 1 Filipino Tekstong Naratibo Sy14-15Document18 pagesGrade 1 Filipino Tekstong Naratibo Sy14-15api-256382279No ratings yet

- DLP 7 Luzon Antas NG WikaDocument11 pagesDLP 7 Luzon Antas NG WikaRichard SalatamosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Metaphysical RealitiesDocument24 pagesLesson 2 Metaphysical RealitiesJennifer OriolaNo ratings yet

- Wowie A. Biduan: Personal InformationDocument4 pagesWowie A. Biduan: Personal Informationmawie biduanNo ratings yet

- M2R1 Bonifacio-P.-sibayan in FishmanDocument33 pagesM2R1 Bonifacio-P.-sibayan in FishmanHannah Jerica CerenoNo ratings yet

- I Am Proud To Be A Filipino - Worksheet No.3Document2 pagesI Am Proud To Be A Filipino - Worksheet No.3JoyjosephGarvidaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Including Culture in e 0238eeccDocument13 pagesThe Importance of Including Culture in e 0238eeccFabian KoLNo ratings yet

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDocument10 pagesEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldRoseAnnPletadoNo ratings yet

- Blake PhilippineLiterature 1911Document10 pagesBlake PhilippineLiterature 1911Aubrey DillaNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (20page)Document20 pages21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (20page)May RuselleNo ratings yet

- Basic Types of Literary Criticsm (5pages)Document5 pagesBasic Types of Literary Criticsm (5pages)May RuselleNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticsm A New History by Gary Day (353pages)Document353 pagesLiterary Criticsm A New History by Gary Day (353pages)May Ruselle100% (1)

- LET Social StudiesDocument119 pagesLET Social StudiesMay Ruselle100% (6)

- Consumer Electronics Learning ModuleDocument153 pagesConsumer Electronics Learning ModuleNick Bantolo50% (2)

- Food Processing NC IIDocument93 pagesFood Processing NC IIMay Ruselle100% (1)

- Ict 10 LM PDFDocument334 pagesIct 10 LM PDFMay RuselleNo ratings yet

- Eng10 LM U4Document54 pagesEng10 LM U4May RuselleNo ratings yet

- LM Mason 10 Final PDFDocument112 pagesLM Mason 10 Final PDFMay RuselleNo ratings yet

- Civil Service Reviewer 2018 PDFDocument304 pagesCivil Service Reviewer 2018 PDFMay Ruselle100% (1)

- Part 2. Providing Support and Challenge When Selecting and Using Materials PDFDocument8 pagesPart 2. Providing Support and Challenge When Selecting and Using Materials PDFMaksym BuchekNo ratings yet

- Thelema 93 - Flight 93 - Lawrence Connor - 2009Document6 pagesThelema 93 - Flight 93 - Lawrence Connor - 2009Wolf Gant100% (1)

- Curriculum Vitae: MD Masum Reza S/o-Rezaul KarumDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: MD Masum Reza S/o-Rezaul KarumSintu DasNo ratings yet

- Critical Book Report Poetry Appreciation: Languages and Arts Faculty State University of MedanDocument10 pagesCritical Book Report Poetry Appreciation: Languages and Arts Faculty State University of MedanJimmy SimanungkalitNo ratings yet

- HadomiDocument2 pagesHadomiMaggie JolyNo ratings yet

- Management of Academic and Cocurricular Excellence OumDocument5 pagesManagement of Academic and Cocurricular Excellence OumSyful AmadeusNo ratings yet

- Course Title: Anthropology Course Code: Anth 1012: Prepared by Mamush DDocument209 pagesCourse Title: Anthropology Course Code: Anth 1012: Prepared by Mamush DAbdi JifarNo ratings yet

- Honorpledgeexamples PDFDocument2 pagesHonorpledgeexamples PDFLouie GirayNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Science in Accountancy: Program Curriculum Ay 2020 - 2021Document5 pagesBachelor of Science in Accountancy: Program Curriculum Ay 2020 - 2021Rosemarie AngelesNo ratings yet

- 07 Chapter 1Document22 pages07 Chapter 1Harinder Singh HundalNo ratings yet

- Channels, Types and Forms of Business Communication PDFDocument36 pagesChannels, Types and Forms of Business Communication PDFGazala KhanNo ratings yet

- BBUS 421 - Chapter 1 - Consumer Behavior and Marketing StrategyDocument13 pagesBBUS 421 - Chapter 1 - Consumer Behavior and Marketing StrategyHai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Musica GiapponeDocument339 pagesMusica Giapponeboto25100% (1)

- Examining Student Satisfaction With The Student Services Center at A Local Community CollegeDocument1 pageExamining Student Satisfaction With The Student Services Center at A Local Community CollegeAngeline LedeirreNo ratings yet

- Educ 3 AssignmentDocument10 pagesEduc 3 AssignmentJera Obsina100% (1)

- The 30 Second Elevator SpeechDocument4 pagesThe 30 Second Elevator Speechmastermind_asia9389No ratings yet

- Agamben Means Without EndDocument82 pagesAgamben Means Without Endeuagg100% (2)

- Content Analysis: Method, Applications, and Issues: Health Care For Women InternationalDocument10 pagesContent Analysis: Method, Applications, and Issues: Health Care For Women InternationalLenin GuerraNo ratings yet

- About Kuraldal FestivalDocument3 pagesAbout Kuraldal FestivalAshley Gabriel BascoNo ratings yet

- On Teaching A Language Principles and Priorities in MethodologyDocument33 pagesOn Teaching A Language Principles and Priorities in MethodologyYour Local MemeistNo ratings yet

- Situational EthicsDocument1 pageSituational EthicsAngelo Garret V. LaherNo ratings yet

- Public International LawDocument3 pagesPublic International LawST100% (1)

- CNAS - 23 - 01 - 06-Ocr Nepal - ToffinDocument24 pagesCNAS - 23 - 01 - 06-Ocr Nepal - ToffinthersitesNo ratings yet

- Ralph Waldo EmersonDocument5 pagesRalph Waldo Emerson0746274107No ratings yet