Professional Documents

Culture Documents

65 Years of FREEDOM - Dailynews - LK

Uploaded by

ramaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

65 Years of FREEDOM - Dailynews - LK

Uploaded by

ramaCopyright:

Available Formats

M o n d a y, 4 Fe b r u a r y 2 0 1 3

Home | S H A R E M A R K E T | E X C H A N G E R AT E | T R A D I N G | O T H E R P U B L I C AT I O N S | A R C H I V E S |

Google

DAILYNEWS

ONLINE

News

Editorial

Business

Features

INDEPENDENCE MOVEMENT OF PRE-SRI LANKA Related Stories |

Home

Political

V R Sarath Chandra ON E LA ND , ON E FL AG ,

Security

ON E HE A RT

Sport The Sri Lankan independence movement was a peaceful political movement

LO N G J OU R NE Y TO

World which aimed at achieving independence and self-rule for Ceylon from the

F R EE DO M

Letters British Empire. It was initiated around the turn of the 20th century lead

Obituaries

mostly by the educated middle class and ultimately was successful when T UR NING PO INT IN

C U LT U R E AN D AR T S

February 4, 1948 Ceylon was granted independence as the Dominion of

OTHER

Ceylon. Dominion status within the British Commonwealth was retained for C e yl on ' s j o ur ne y t o

PUBLICATIONS the next 24 years until May 22, 1972 when it became a republic and was In d e p e nd e n ce

renamed the Republic of Sri Lanka.

OTHER LINKS S R I LA NK A IN 20 4 8 !

The British Raj was dominant in Asia after the Battle of Assaye; following the

S I XT Y F IFT H N at i on a l

Battle of Waterloo the British Empire became the world superpower. Its D AY !

appearance of omnipotence was only briefly dented by setbacks in India,

Afghanistan and South Africa. It was virtually unchallenged until 1914. IN D EP EN DE N CE OF TH E

AR T S

The formation of the EP IC H E R O IS M O F

Batavian Republic in the P A T R IO T S

Netherlands as an ally

S O VER EI G N T Y - C OLO NY

and of the French - S OV E R EI G NT Y

Directory, led to a British

attack on Ceylon in 1795 ‘ F REE DO M IS A

R E SP ON S IB ILIT Y ’

as part of England's war

against the French IN D EP EN DE N CE

Republic. The Kandyan M O V EME NT O F P R E -SR I

LA N K A

Kingdom collaborated

with the British P R ES ID E NT M AH IND A

expeditionary forces R A J AP AK S A

R E SU S C IT A T E D AN D

against the Dutch, as it

R E V IVE D T H E

had with the Dutch IN D EP EN DE N CE OF

against the Portuguese. 1 94 8

P R O JE CT IN G

Once the Dutch had

EX P EC T AT IO N S T O N E W

been evicted, their sovereignty ceded by the Treaty of Amiens and HE IG H T S

subsequent revolts in the low-country suppressed, the British began planning

to capture the Kandyan Kingdom. The 1803 and 1804 invasions of the

Kandyan provinces in the 1st Kandyan War were bloodily defeated. In 1815,

the British fomented a revolt by the Kandyan aristocracy against the last

Kandyan

EMAIL | monarch

P R I N T A B L E and marched

VIEW |

F E E D B Ainto

C K | uplands to depose him in the 2nd

KandyanShare

Follow War. 75K people are following this. Be the first of your friends to follow

this

The struggle against the colonial power began in 1817 with the Uva

Rebellion, when the same aristocracy rose against British rule in a rebellion

in which their villagers participated.

| News |

EditorialThey were

|

Business defeated

|

Features by

|

Political the occupiers.

|

Security |

Sport |

WorldAn

|

Letters |

Obituaries |

attempt at rebellion sparkedProduced

again bybriefly in Copyright

Lake House 1830. ©The 2013Kandyan

The Associatedpeasantry

Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd.

were stripped of their lands by the Comments Wastelands Ordinance,

and suggestions a modern

to :

Web Editor

enclosure movement and reduced to penury.

In 1848 the abortive Matale Rebellion, led by Hennedige Francisco Fernando

(Puran Appu) and Gongalegoda Banda was the first transitional step towards

abandoning the feudal form of revolt, being fundamentally a peasant revolt.

The masses were without the leadership of their native King (deposed in

1815) or their chiefs (either crushed after the Uva Rebellion or collaborating

with the colonial power).

The leadership passed for the first time in the Kandyan provinces into the

hands of ordinary people, non-aristocrats. The leaders were yeomen-

artisans, resembling the Levellers in England's revolution and mechanics

such as Paul Revere and Tom Paine who were at the heart of the American

Revolution. However, in the words of Colvin R. de Silva, ‘it had leaders but

no leadership. The old feudalists were crushed and powerless. No new class

capable of leading the struggle and heading it towards power had yet arisen.’

In the 1830s, coffee was introduced into Sri Lanka, a crop which flourishes in

high altitudes, and grown on the land taken from the peasants. The principal

impetus to this development of capitalist production in Sri Lanka was the

decline in coffee production in the West Indies, following the abolition of

slavery there.

However, the dispossessed peasantry were not employed on the plantations:

The Kandyan villagers refused to abandon their traditional subsistence

holdings and become wage-workers in the nightmarish conditions that

prevailed on these new estates, despite all the pressure exerted by the

colonial state. The British therefore had to draw on its reserve army of

labour in India, to man its lucrative new outpost to the south. An infamous

system of contract labour was established, which transported hundreds of

thousands of Tamil ‘coolies’ from southern India into Sri Lanka for the coffee

estates. These Tamils labourers died in tens of thousands both on the

journey itself as well as on the plantations.

The coffee economy collapsed in the 1870s, when coffee blight ravaged the

plantations, but the economic system it had created survived intact into the

era of its successor, tea which was introduced on a wide scale from 1880

onwards.

Tea was more capital-intensive and needed a higher volume of initial

investment to be processed, so that individual estate-owners were now

supplanted by large English consolidated companies based either in London

(‘sterling firms’) or Colombo (‘rupee firms’). Monoculture was thus

increasingly capped by monopoly within the plantation economy.

The pattern thus created in the 19th century remained in existence down to

1972. The only significant modification to the colonial economy was the

addition of a rubber sector in the mid-country areas. A new body of urban

capitalists was growing in the low country, around shop-keeping and the

alcohol and wood-work industries. These entrepreneurs were from many

castes and they strongly resented the historically unprecedented and

unbuddhistic practice of ‘caste discrimination’ adopted by the Siam Nikaya in

1764, just 10 years after it had been established by a Thai monk. Around

1800 they organised the Amarapura Nikaya, which became hegemonic in the

low-country by the mid-19th century.

The British attempt at giving a Protestant Christian education to the young

men of the commercial classes backfired, as they transformed the Buddhism

practised in Sri Lanka into something resembling the non-conformist

Protestant model. A series of debates against clergymen of the established

Anglican church was organised, culminating in the defeat of the latter by

modern logical argument.

The Buddhist revival was aided by the Theosophists, led by American Col.

Henry Steel Olcott, who helped establish Buddhist schools such as Ananda

College, Colombo; Dharmaraja College, Kandy; Maliyadeva College,

Kurunegala; Mahinda College, Galle;and Musaeus College, Colombo; at the

same time injecting more modern secular western ideas into the ‘Protestant’

Buddhist thoughtstream.

You might also like

- The Story of The Indian Press PDFDocument4 pagesThe Story of The Indian Press PDFJanardhan Juvvigunta JJNo ratings yet

- La Atalaya de 1924Document385 pagesLa Atalaya de 1924Ricardo LopezNo ratings yet

- Age of DemocracyDocument22 pagesAge of Democracyjyoung-wooster7859No ratings yet

- The Mexican Ministry of EducatDocument314 pagesThe Mexican Ministry of EducatLisset HeroNo ratings yet

- Rebellion, Revolution, and Armed Force: A Comparative Study of Fifteen Countries with Special Emphasis on Cuba and South AfricaFrom EverandRebellion, Revolution, and Armed Force: A Comparative Study of Fifteen Countries with Special Emphasis on Cuba and South AfricaNo ratings yet

- Leonardo Da Vinci: Scotland The Brave: Bannockburn 1314Document100 pagesLeonardo Da Vinci: Scotland The Brave: Bannockburn 1314jorge bobadillaNo ratings yet

- Law, R Ouidah The Social History of A West African Slaving Port 1727-1892Document161 pagesLaw, R Ouidah The Social History of A West African Slaving Port 1727-1892Moises Correa Fonseca da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Fierce Hand-to-Hand Fighting - Rages in Germany As Yankees Battle For Gateway To CologneDocument10 pagesFierce Hand-to-Hand Fighting - Rages in Germany As Yankees Battle For Gateway To CologneOSANTIZO315No ratings yet

- The Americans Unit 5 PDFDocument108 pagesThe Americans Unit 5 PDFDvr IsisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Our Worldviews Grade 8Document40 pagesChapter 4 Our Worldviews Grade 8Aarna SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Work Revolution Coursework For HIS2104: QUESTION: To What Extent Is The Industrial Revolution in Japan A Result of Internal Factors?Document10 pagesWork Revolution Coursework For HIS2104: QUESTION: To What Extent Is The Industrial Revolution in Japan A Result of Internal Factors?charlesokello.the1stNo ratings yet

- 5 He-Man Vs Skeletor Their Final BattleDocument9 pages5 He-Man Vs Skeletor Their Final BattleRodrigo Sorokin100% (2)

- Group 1 - History of ScotlandDocument9 pagesGroup 1 - History of ScotlandLinh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- J.J. Coulton - The West Court at Perachora - BSA 62 1967Document35 pagesJ.J. Coulton - The West Court at Perachora - BSA 62 1967MehmetGürbüzerNo ratings yet

- 02Document237 pages02Arko HossainNo ratings yet

- History in FocusDocument12 pagesHistory in FocusCedricxsavage adedugbaNo ratings yet

- Parties and The Party Systems in IndiaDocument38 pagesParties and The Party Systems in IndiaAmoureux ÂmeNo ratings yet

- How It Works Book of Aircraft 2nd ED 2016 UK PDFDocument148 pagesHow It Works Book of Aircraft 2nd ED 2016 UK PDFDEBAJYOTI NAYAKNo ratings yet

- Antarctica IntermediateDocument1 pageAntarctica IntermediatealyahalhamadiNo ratings yet

- English 2769Document4 pagesEnglish 2769YayyNo ratings yet

- Nepal: Between Dictatorship and AnarchyDocument16 pagesNepal: Between Dictatorship and AnarchyRahul RawatNo ratings yet

- 1-5 Japanese PeriodDocument13 pages1-5 Japanese PeriodCherub DaramanNo ratings yet

- Rizal 2ND LessonDocument35 pagesRizal 2ND LessonPrince ChuaNo ratings yet

- The Govt Act 1935Document52 pagesThe Govt Act 1935A.SinghNo ratings yet

- Ryle and Amuom - Peace Is The Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local ResponsDocument124 pagesRyle and Amuom - Peace Is The Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local ResponsjohnrryleNo ratings yet

- The Blood of The People - Revolution and The End of Traditional Rule in Northern SumatraDocument330 pagesThe Blood of The People - Revolution and The End of Traditional Rule in Northern SumatraanggaturanaNo ratings yet

- Social Studies BookDocument27 pagesSocial Studies Bookapi-295440709No ratings yet

- Modern Japan East Asian StudiesDocument12 pagesModern Japan East Asian Studies19KANISHKNo ratings yet

- Dawn of Filipino NationalismDocument4 pagesDawn of Filipino NationalismRav Evan VigillaNo ratings yet

- ThailandDocument31 pagesThailandBlack HornetNo ratings yet

- Souvener 2009 BDocument50 pagesSouvener 2009 Bapi-19766918100% (1)

- Group 4 Final PDFDocument33 pagesGroup 4 Final PDFPaul PontemayorNo ratings yet

- Ruler Visibility and Popular Belonging in The Ottoman Empire, 1808-1908Document250 pagesRuler Visibility and Popular Belonging in The Ottoman Empire, 1808-1908zinedinezidane.19978No ratings yet

- Ucup 6299Document7 pagesUcup 6299FajarNo ratings yet

- Flags of America From The Time of Columbus To Present Day 1926Document34 pagesFlags of America From The Time of Columbus To Present Day 1926Marie AnnaNo ratings yet

- Burckhardt CivilizationDocument22 pagesBurckhardt CivilizationeszterNo ratings yet

- Region 1Document41 pagesRegion 1Catherine OcampoNo ratings yet

- Bank 4386Document4 pagesBank 4386Ekky Rahmat PrimantokoNo ratings yet

- FORM 2 Grade5 With ConsolDocument70 pagesFORM 2 Grade5 With ConsolMelieza Melody AmpanNo ratings yet

- Palestine IssueDocument3 pagesPalestine Issuemian jamil ur-rehmanNo ratings yet

- The War With MexicoDocument6 pagesThe War With Mexicoapi-445403009No ratings yet

- Fried - Chicken - July2023 (Cincinnati Magazine)Document1 pageFried - Chicken - July2023 (Cincinnati Magazine)John FoxNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 - Case Study1 - JapanDocument22 pagesChapter1 - Case Study1 - JapanHenrique AbreuNo ratings yet

- Kriminologi 1227Document3 pagesKriminologi 1227ariq abbadNo ratings yet

- BKBC 2471Document4 pagesBKBC 2471Agiel AsmaraNo ratings yet

- Pendahuluan - Jenis-Jenis AliranDocument25 pagesPendahuluan - Jenis-Jenis Aliranfadli fauzanNo ratings yet

- Mekflud 2 Full PDFDocument444 pagesMekflud 2 Full PDFPratama Jr.No ratings yet

- Mcclain: ModernDocument760 pagesMcclain: ModernHISTORY TVNo ratings yet

- A Brief Overview of JapanDocument4 pagesA Brief Overview of JapannothingNo ratings yet

- 2g 2 Group 2 PresentationDocument37 pages2g 2 Group 2 PresentationMorales, Glayzelle V.No ratings yet

- Group 5 - Task PerformanceDocument15 pagesGroup 5 - Task PerformanceGerald Ramirez ApolinarNo ratings yet

- Group 2 International Cuisine 123Document46 pagesGroup 2 International Cuisine 123Daniella FirmeNo ratings yet

- Japan Returns To IsolationDocument2 pagesJapan Returns To Isolationapi-226556152No ratings yet

- 1898 Declaration of Philippine IndependenceDocument52 pages1898 Declaration of Philippine IndependenceJhannea BiocoNo ratings yet

- Great English Monarchs - Green Apple PDFDocument114 pagesGreat English Monarchs - Green Apple PDFAna Maria KovacsNo ratings yet

- Tibet - Dalai Lama, Freedom in ExileDocument296 pagesTibet - Dalai Lama, Freedom in ExileThomas Kurian100% (1)

- Have A Pleasant Stay in Sri Lanka : For Sri Lankans, Dual Citizens and Foreign NationalsDocument3 pagesHave A Pleasant Stay in Sri Lanka : For Sri Lankans, Dual Citizens and Foreign NationalsramaNo ratings yet

- Perani Widyawa Saha Thakshana Final 1Document10 pagesPerani Widyawa Saha Thakshana Final 1ramaNo ratings yet

- Revolt On The Razor's Edge - Daily NewsDocument24 pagesRevolt On The Razor's Edge - Daily NewsramaNo ratings yet

- Our LeadersDocument11 pagesOur LeadersramaNo ratings yet

- Independence of 1948 Revived - Daily FTDocument7 pagesIndependence of 1948 Revived - Daily FTramaNo ratings yet

- Lasting Monuments of Sri Lanka's IndependenceDocument3 pagesLasting Monuments of Sri Lanka's IndependenceramaNo ratings yet

- Stories of Our National HeroesDocument2 pagesStories of Our National HeroesramaNo ratings yet

- Features - Online Edition of Daily News - Lakehouse NewspapersDocument2 pagesFeatures - Online Edition of Daily News - Lakehouse NewspapersramaNo ratings yet

- HENRY STEEL OLCOTT (1832 - 1907) - TS AdyarDocument7 pagesHENRY STEEL OLCOTT (1832 - 1907) - TS AdyarramaNo ratings yet

- Praxis Jul Dec 3011 FADocument96 pagesPraxis Jul Dec 3011 FAachmade zakryNo ratings yet

- Pasay CityDocument4 pagesPasay CityPaul Michael Camania JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Disguise For CoverDocument4 pagesDisguise For CoverMfayyadhNo ratings yet

- 7367-V-Development of Conflict in Arab Spring Libya and Syria From Revolution To Civil WarDocument22 pages7367-V-Development of Conflict in Arab Spring Libya and Syria From Revolution To Civil WarFederico Pierucci0% (1)

- Outline - Rectos Nationalism and Historic PastDocument11 pagesOutline - Rectos Nationalism and Historic PastVincent Luigil AlceraNo ratings yet

- Workforce Diversity in India at IBMDocument43 pagesWorkforce Diversity in India at IBMAbhilash GargNo ratings yet

- Reflections On MarxismDocument41 pagesReflections On MarxismRech SarzabaNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument11 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Patriarchy in MSNDDocument37 pagesPatriarchy in MSNDHajer MrabetNo ratings yet

- Refugees Tvet Self-Assessment ToolDocument33 pagesRefugees Tvet Self-Assessment ToolMearg NgusseNo ratings yet

- Fisher Sources of Conflict and Methods of ResolutionDocument6 pagesFisher Sources of Conflict and Methods of ResolutionRajkumar CharzalNo ratings yet

- Component B Laying The FoundationDocument19 pagesComponent B Laying The Foundationrodel d hilarioNo ratings yet

- New-flat-Template-ENGLISH OrangeDocument12 pagesNew-flat-Template-ENGLISH OrangesusaineNo ratings yet

- Arbitration - Conciliation and AdrDocument12 pagesArbitration - Conciliation and Adrmeenakshi kaur0% (2)

- ICTimes May 07Document24 pagesICTimes May 07api-3805821100% (1)

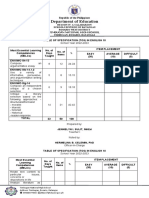

- Table of Specification-ThirdDocument2 pagesTable of Specification-ThirdJennelyn SulitNo ratings yet

- Water Logging Problem in ZigatolaDocument7 pagesWater Logging Problem in ZigatolaBristy MarihaNo ratings yet

- Management 13th Edition Robbins Test BankDocument26 pagesManagement 13th Edition Robbins Test BankJohnJamesscoz100% (56)

- Sei Fuji v. CaliforniaDocument1 pageSei Fuji v. CaliforniacrlstinaaaNo ratings yet

- Merkel Is Jewish: - High Priest Mageson 666Document8 pagesMerkel Is Jewish: - High Priest Mageson 666Anonymous nKqPsgySlENo ratings yet

- Course Title: Service To The Nation ThroughDocument8 pagesCourse Title: Service To The Nation ThroughMayls De LeonNo ratings yet

- Vietnam - Student Notes Presentation - 2 of 2Document21 pagesVietnam - Student Notes Presentation - 2 of 2api-332186475No ratings yet

- The Glory of Africa Part 3Document64 pagesThe Glory of Africa Part 3Timothy100% (2)

- GSR 2016 Full Report PDFDocument272 pagesGSR 2016 Full Report PDFEG. A 2015No ratings yet

- Social InteractionDocument17 pagesSocial InteractionPiyush AgarwalNo ratings yet

- The Century - The Best Years 1946 To 1952 - QuestionsDocument2 pagesThe Century - The Best Years 1946 To 1952 - QuestionsCharles CogginsNo ratings yet

- Model c1 TpsDocument23 pagesModel c1 TpsMiela Aninizza KhamielNo ratings yet

- Orasm KurdishDocument10 pagesOrasm KurdishshallawNo ratings yet

- The Social Contract by Thomas HobbesDocument1 pageThe Social Contract by Thomas HobbesHazel Michaela CalijaNo ratings yet

- Genealogy of Morals EssayDocument3 pagesGenealogy of Morals EssaymgxipellNo ratings yet

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisFrom EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (49)

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorFrom EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (77)

- Project MK-Ultra: The History of the CIA’s Controversial Human Experimentation ProgramFrom EverandProject MK-Ultra: The History of the CIA’s Controversial Human Experimentation ProgramRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureFrom EverandDunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Desperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarFrom EverandDesperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- The Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideFrom EverandThe Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideNo ratings yet

- Midnight in Chernobyl: The Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear DisasterFrom EverandMidnight in Chernobyl: The Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear DisasterRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (410)

- The Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarFrom EverandThe Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicFrom EverandKnowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- The Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953From EverandThe Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953No ratings yet

- Rebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldFrom EverandRebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Hubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandHubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Empire of Destruction: A History of Nazi Mass KillingFrom EverandEmpire of Destruction: A History of Nazi Mass KillingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaFrom EverandWe Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarFrom EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln's Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby's Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America's Special OperationsFrom EverandThe Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln's Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby's Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America's Special OperationsNo ratings yet

- Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsFrom EverandMaking Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsNo ratings yet

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIFrom EverandWitness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesFrom EverandThe Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyFrom EverandDigital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (51)

- They All Love Jack: Busting the RipperFrom EverandThey All Love Jack: Busting the RipperRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)

- Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailFrom EverandPrinciples for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (239)

- Mafia Spies: The Inside Story of the CIA, Gangsters, JFK, and CastroFrom EverandMafia Spies: The Inside Story of the CIA, Gangsters, JFK, and CastroRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (35)

- The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaFrom EverandThe Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtFrom Everand1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)