Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Contrastive Analysis of The "Head" in English and Uzbek Languages

Uploaded by

Dilnoza QurbonovaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Contrastive Analysis of The "Head" in English and Uzbek Languages

Uploaded by

Dilnoza QurbonovaCopyright:

Available Formats

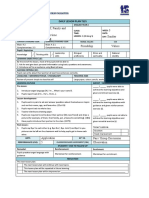

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236

Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 7.624

CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE “HEAD” IN ENGLISH AND UZBEK LANGUAGES

Narzullayeva Firuza Olimovna,

Lecturer of the department Translation studies and Language education at Bukhara

State University, Uzbekistan

ABSTRACT: This article describes somatic lexical units in Uzbek and English, containing in

their composition a component with the meaning "head". This article considers cases of

using lexical units with somatic component "head" / "bosh" in English and Uzbek languages;

contrastive analysis of somanticisms in English and Uzbek languages.

KEY WORDS: Somatism, phraseological unit, somatic, head component, analysis, structure,

lexico-semantic group, phraseological unit, phrase formation, model.

INTRODUCTION

Somatisms belong to "the oldest layers of phraseology" and form the largest

subgroup of phraseologisms in English and Uzbek. Beyond this remarkable quantitative

aspect, they are of linguistic interest above all because their images derive from that

physical, directly experienced and comprehensible human corporeality that plays a major

role in our conceptualization of the world in all cultures. They are thus among those special

phraseologisms that Lakoff calls “imageable idioms”. Or to put it another way: they are

characterized by a high degree of pictoriality. In general, somatisms have developed quite

differently in different languages. This is even true for the European language family,

although it not only shares the cultural heritage of Hippocrates and Galen of Pergamum, but

above all also the etymological origins of the designations of body parts, the vast majority of

which go back to the Indo-European period.

It can be stated: With regard to a general and comprehensive theory of somatisms,

the somatemes would have to be arranged according to a typology of imagery that also

includes the various degrees of their formability. If the symbol has the lowest degree of

freedom in this respect and thus at the same time the lowest degree of use, this

characteristic also applies to the so-called kinegrams, in which conventionalized gestures

and facial expressions are found. The metonymic use of somatemes is - compared to that of

symbols - a larger creative space, even if their limits are given by the fact that they always

have to refer to the human being as a whole. The broadest spectrum, however, is certainly

Vol. 11 | No. 5 | May 2022 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 25

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236

Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 7.624

inherent in the somatic metaphors, which result from the variety of functions of certain

parts of the body - such as the head, the hand and the mouth - and develop their variants in

the free play between the areas of meaning: The pictorial idea that the head as the

supposed seat of the mind sometimes gets lost under the pressure of emotions, leading to

somatism in many European languages to lose one's head. The fact that he figuratively

threatens to fall apart when he is overloaded reflects in some the somatism racking his

brains. In English, one improvises off the top of one's head off the top of one's head and

makes others laugh one's head off are based, form a broad field of work for contrastive

somatology. The need to develop meaningful categories and scales, according to which

classification and grading can be carried out in an interlingual comparison, is particularly

important for them. But this is exactly what proves their semantic richness, which they owe

to the fundamental role of the human body in ordering reality and describing experiences in

this reality. Body part designations form one of the oldest layers of the vocabulary of any

language. Parallel to their biological functions, human body parts or organs are also used for

the symbolic expression of various issues and are conceptualized as the seat of emotional

and mental activity. There is a growing interest in researching the historical and cultural

foundations of human cognition, taking into account cultural traditions and models.

MAIN BODY

In everyday language, somatisms, i.e., phraseologisms that contain a body part as a

component, are used especially in spoken language. The translatability of these formulaic

constituents is sometimes problematic due to their complex lexical and semantic

composition and sociocultural differences. Translators and language teachers are constantly

faced with the challenge of having to search for possible equivalence in the target language.

Idioms are constituents that usually have a connotative meaning in addition to their

denotative meaning. Like proverbs, they are anonymous rhetorical figures whose origin, i.e.,

by whom, when and where they were first used, is unknown. Idioms consist of at least two

words that carry influencing as a function. The cultural characteristics of a community are

reflected in the words or word groups that can be found as idioms in everyday life. These

phrases present a situation or location in a concise and understandable way and only

become understandable against their specific, cultural background. Idioms that have been

Vol. 11 | No. 5 | May 2022 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 26

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236

Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 7.624

used in the history of the community and are no longer relevant today thus open up cultural

interpretations and peculiarities of the past.

A large number of somatic idioms, which have been spread by word of mouth as

cultural heritage, are now regarded as universal, cultural peculiarities. That is why the

idioms have a special status in translation. An equivalent translation must be found for the

formulaic constituents. They usually cannot be translated literally, as they can differ in their

structure and meaning. For this reason, idioms that do not correspond in form and meaning

are often translated incorrectly. For the translation of the idioms, it is necessary to find the

equivalent in the target language. If this equivalent cannot be found, refer to the helpful

method of finding a word or even a phrase that represents the meaning of the idiom.

However, it is a fact that nowadays several dictionaries are needed to ensure an adequate

translation.

Phraseologically active somatisms have a developed polysemy, and also realize in

phraseological units a significant part of their meanings, however, the somatism “head” we

are considering, having the following values, implements only two of them, that is, less than

half.

Consider the meaning of this somatism in the dictionary:

1. the upper part of the human body, or the front or upper part of the body of an animal,

typically separated from the rest of the body by a neck, and containing the brain, mouth,

and sense organs.

2. a thing resembling a head either in form or in relation to a whole.

3. the front, forward, or upper part or end of something.

4. a person in charge of something; a director or leader.

5. a person considered as a numerical unit.

6. a component in an audio, video, or information system by which information is

transferred from an electrical signal to the recording medium, or vice versa.

In Uzbek and English, the head is represented as the main organ of human thought.

In this regard, the main connotative meaning of somatism, it means prudence and mind or

their absence. Therefore, this lexeme is the most productive when description of a person's

intellect in terms of his appearance.

Vol. 11 | No. 5 | May 2022 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 27

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236

Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 7.624

Often the "head" takes on the meaning of life, because it is a vital organ, for

example, to pay for smth. with one's life "boshi bilan javob bermoq" Seme brings additional

value superiority inherent in the concept, for example: to carry one's head high - "boshini

baland tutmoq", "o’zini mag’rur turmoq", to wash one's head - "kimningdir boshini egmoq,

ham qilmoq”.

It should be noted that among the analogues of Uzbek phraseological units about the

head in English, sometimes it is the head that corresponds to it, and sometimes the brains,

for example: to cudgel one’s brains over something - “biror narsa ustida bosh qotirmoq”, use

your brains – “kallangni ishlat”, “aqlingni ishlat”.

Somatic phraseological units are widely represented in the studied our languages, but not

always in them somatisms are key, in other words, sometimes their role is optional. Typical

structure phraseological units with key somatisms are comparative (to keep one's head -

"xotirjam bo’lmoq", literally "boshni saqlamoq") and gestural phraseological units owing

their origin to the free phrases (to shake one's head - "bosh chayqamoq" = a sign of

disagreement, to hang one's head – “boshini egmoq”, “boshni quyi solmoq” = a sign of

sadness, sadness).

Most cultures tend to perceive the head as the main and the most vital part of the

body. The languages we study are not exception. The fact that the head is associated with

the idea of brain, one of the main functions of which is the function thinking, largely

determines the lexico-semantic the potential of this word as a supporting component of

somatic phraseological units. The lexeme "head" is a part of various structure and lexical

and grammatical features of combinations. Phraseological units that have a noun in their

composition "head", characterized by the expression of a rich range of feelings, spiritual the

state of a person and his attitude to surrounding phenomena, positive or negative

assessment of actions and actions and are mainly associated with concept of mental activity.

Most somatisms in Uzbek and English are the same its logical structure, for example:

a fish rots from the head - “baliq boshidan sasiydi.” Some somatisms coincide in their logical

structure, but differ in the components themselves, for example: many men, many minds –

“bir kalladan ikkitasi yaxshi”.

Vol. 11 | No. 5 | May 2022 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 28

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236

Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 7.624

CONCLUSION

Thus, the cultural-national interpretation of the lexical-phraseological somatic space

allows us to understand mechanisms involved in the formation of a picture of the world,

including huge role of a person in self-knowledge, knowledge of the real world, his

worldview and worldview of a person and an ethnic group as a whole.

English and Uzbek phraseological units of the lexical-semantic field of "body parts"

represent a huge group phraseological units with specific features. Among them there are

phraseological units of all types: phraseological unions, unity and combinations. Greatest

the number of somatic phraseological units of the compared languages are phraseological

units. They are different in their origin: bibleisms, mythologisms, phraseological units

formed by rethinking in one of the compared languages. Phraseological units of English and

Uzbek languages with component "part of the body" have increased interlingual

phraseological equivalence. This is because the nuclei (i.e., words - names of body parts) are

included in the high-frequency and primordial vocabulary each of the languages are similarly

comprehended in the culture of both European countries and have a high phrase-forming

activity, which increases degree of interlingual equivalence.

REFERENCE:

1. Nafisa, K. . (2021). Semantics and Pragmatics of a Literary Text. Middle European

Scientific Bulletin, 12, 374-378.

2. Nafisa K. Cognition and Communication in the Light of the New Paradigm

//EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF INNOVATION IN NONFORMAL EDUCATION. – 2021. – Т. 1.

– №. 2. – С. 214-217.

3. Firuza N. Polysemy and its types in the non-related languages //Middle European

Scientific Bulletin. – 2021. – Т. 12. – С. 529-533.

4. Firuza N. English Phraseological Units With Somatic Components //Central Asian

Journal Of Literature, Philosophy And Culture. – 2020. – Т. 1. – №. 1. – С. 29-31.

5. Khamroyevna, K. L. (2021). The Analysis of Education System in Uzbekistan:

Challenges, Solutions and Statistical Analysis. European Journal of Life Safety and

Stability (2660-9630), 9, 90-94. Retrieved from

http://ejlss.indexedresearch.org/index.php/ejlss/article/view/148

Vol. 11 | No. 5 | May 2022 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 29

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236

Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 7.624

6. Khaydarova L., Joanna I. Dark Tourism: Understanding the concept and the demand

of new experiences //ASIA PACIFIC JOURNAL OF MARKETING & MANAGEMENT

REVIEW ISSN: 2319-2836 Impact Factor: 7.603. – 2022. – Т. 11. – №. 01. – С. 59-63.

7. Salixova, N. N. (2019). PECULIAR FEATURES OF TEACHING READING. Theoretical &

Applied Science, (11), 705-708.

8. Imamkulova, Sitora. "The Intensity of Word Meanings." EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF

INNOVATION IN NONFORMAL EDUCATION 1.2 (2021): 227-229.

9. Olimova, D. Z. (2021). Transfer of modality in translation (modal verbs and their

equivalents, modal words). Middle European Scientific Bulletin, 12, 220-22.

10. Fayziyeva Aziza Anvarovna. (2022). CONCEPTUAL METAPHOR UNIVERSALS IN

ENGLISH AND UZBEK. JournalNX - A Multidisciplinary Peer Reviewed Journal, 8(04),

54–57.

11. Xafizovna, R. N. . (2022). Discourse Analysis of Politeness Strategies in Literary Work:

Speech Acts and Politeness Strategies. Spanish Journal of Innovation and Integrity, 5,

123-133.

12. Ruziyeva Nilufar Xafizovna (2021).The category of politeness in different

linguocultural traditions. ACADEMICIA: AN INTERNATIONAL MULTIDISCIPLINARY

RESEARCH JOURNAL 11 (2), 1667-1675

Vol. 11 | No. 5 | May 2022 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 30

You might also like

- English Phraseological Units With Somatic ComponentsDocument3 pagesEnglish Phraseological Units With Somatic ComponentsKhamza NurillaevNo ratings yet

- თეა ვერძაძის პროექტიDocument15 pagesთეა ვერძაძის პროექტილელა ვერბიNo ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis of Somatizm Head, UzbekEnglishDocument8 pagesComparative Analysis of Somatizm Head, UzbekEnglishKhamza NurillaevNo ratings yet

- Paraphrase DDocument4 pagesParaphrase DDilnoza QurbonovaNo ratings yet

- Roman Jakobson's Translation Handbook: What a translation manual would look like if written by JakobsonFrom EverandRoman Jakobson's Translation Handbook: What a translation manual would look like if written by JakobsonRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- 3615-Article Text-6949-1-10-20201223Document13 pages3615-Article Text-6949-1-10-20201223MinSNo ratings yet

- G-67 RadiologyDocument6 pagesG-67 RadiologyNadim AkhterNo ratings yet

- The Physical Foundation of Language: Exploration of a HypothesisFrom EverandThe Physical Foundation of Language: Exploration of a HypothesisNo ratings yet

- Chapter Iii. Contrastive Analysis of Idioms Expressing "Body Parts" in English, Kyrgyz and Russian LanguagesDocument73 pagesChapter Iii. Contrastive Analysis of Idioms Expressing "Body Parts" in English, Kyrgyz and Russian LanguagesIslombek JalilovNo ratings yet

- Challenges To Translate IdiomsDocument9 pagesChallenges To Translate IdiomsOrsi SimonNo ratings yet

- Dmitrij StructureofmetaphorDocument24 pagesDmitrij StructureofmetaphorMartaNo ratings yet

- Seminar 2Document14 pagesSeminar 2Аружан КенжетаеваNo ratings yet

- Problems of Syntactic Analysis of Fixed Phrases in The English Sentence StructureDocument3 pagesProblems of Syntactic Analysis of Fixed Phrases in The English Sentence StructureAcademic JournalNo ratings yet

- Peculiar Features of Metaphorical Phraseological UnitsDocument9 pagesPeculiar Features of Metaphorical Phraseological UnitsresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Unit I. Phraseology As A Science 1. Main Terms of Phraseology 1. Study The Information About The Main Terms of PhraseologyDocument8 pagesUnit I. Phraseology As A Science 1. Main Terms of Phraseology 1. Study The Information About The Main Terms of PhraseologyIuliana IgnatNo ratings yet

- Advanced English Grammar with ExercisesFrom EverandAdvanced English Grammar with ExercisesRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (12)

- Phraseology: Idioms and Proverbs: Unit 8Document15 pagesPhraseology: Idioms and Proverbs: Unit 8Khánh LyNo ratings yet

- Prikazi Knjiga Book Reviews Rezensionen: Marija OmaziüDocument7 pagesPrikazi Knjiga Book Reviews Rezensionen: Marija Omaziügoran trajkovskiNo ratings yet

- Semantic Representation of The Concept Success/Failure in English, German and Georgian SomatismsDocument9 pagesSemantic Representation of The Concept Success/Failure in English, German and Georgian SomatismsInternational Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Studies (IJAHSS)No ratings yet

- Idioms Between Motivation and Translation: Prep. Univ. Oana Dugan, Universitatea "Dunărea de Jos", GalaţiDocument11 pagesIdioms Between Motivation and Translation: Prep. Univ. Oana Dugan, Universitatea "Dunărea de Jos", GalaţiCristina TomaNo ratings yet

- Language, Culture and Meaning Cross-Cultural SemanticsDocument34 pagesLanguage, Culture and Meaning Cross-Cultural SemanticsMałgorzata Dubiel-RączkaNo ratings yet

- Vse Lektsii VmesteDocument23 pagesVse Lektsii VmesteAimira Zhanybek kyzyNo ratings yet

- реферат (phraseological units)Document11 pagesреферат (phraseological units)MariaNo ratings yet

- LexicologieDocument47 pagesLexicologieFrancesca DiaconuNo ratings yet

- Tezis NilufarDocument4 pagesTezis NilufarMakhmud MukumovNo ratings yet

- Идиомы в английском языкеDocument11 pagesИдиомы в английском языкеrsarsarsarsa2006No ratings yet

- First GlossaryDocument4 pagesFirst GlossaryStella LiuNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Higher and Secondary Specialized Education of The Republik of UzbekistanDocument21 pagesMinistry of Higher and Secondary Specialized Education of The Republik of Uzbekistanwolfolf0909No ratings yet

- Lectures 7 8Document16 pagesLectures 7 8Даря ПасічникNo ratings yet

- On Chomsky's Learnability Hypothesis A Karmik Linguistic ReviewDocument6 pagesOn Chomsky's Learnability Hypothesis A Karmik Linguistic Reviewbhuvaneswar ChilukuriNo ratings yet

- Different Features and Interpretation of Phraseological Units With Zoocomponent in English and Uzbek LanguagesDocument6 pagesDifferent Features and Interpretation of Phraseological Units With Zoocomponent in English and Uzbek LanguagesCentral Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- A Semiotics of Aspects of English and Yoruba Proverbs Adeyemi DARAMOLADocument10 pagesA Semiotics of Aspects of English and Yoruba Proverbs Adeyemi DARAMOLACaetano RochaNo ratings yet

- Proverbs and Idioms in Cultural AwarenessDocument10 pagesProverbs and Idioms in Cultural Awarenessrextlexx122100% (1)

- The English Phraseology.Document13 pagesThe English Phraseology.zlatoustamazutovaNo ratings yet

- PhraseologyDocument14 pagesPhraseologyiasminakhtar100% (1)

- Morphology UuDocument31 pagesMorphology UuLaksmiCheeryCuteizNo ratings yet

- Idioms With TasksDocument16 pagesIdioms With Tasksrsarsarsarsa2006No ratings yet

- Cognitive Linguistic and Idioms-AranjatDocument7 pagesCognitive Linguistic and Idioms-AranjatBranescu OanaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of Language': David CrystalDocument7 pagesThe Structure of Language': David CrystalPetr ŠkaroupkaNo ratings yet

- Classification of Phraseological Units in Linguistics: DOI 10.51582/interconf.19-20.06.2022.024Document7 pagesClassification of Phraseological Units in Linguistics: DOI 10.51582/interconf.19-20.06.2022.024Юля ТвердохлібNo ratings yet

- Lexicology LecturesDocument43 pagesLexicology LecturesСашаNo ratings yet

- Poltava National Pedagogic University of Name of V. G. KorolenkoDocument16 pagesPoltava National Pedagogic University of Name of V. G. KorolenkoАнастасия НизюкNo ratings yet

- Book Review Semantics Palmer PishtiwanDocument21 pagesBook Review Semantics Palmer Pishtiwanlavica13100% (3)

- Advance Studies in Language and LiteratureDocument16 pagesAdvance Studies in Language and Literaturemarco medurandaNo ratings yet

- Mental Grammar Trabajo IIDocument3 pagesMental Grammar Trabajo IIMayte Flores0% (1)

- SL20 The Proverb and Its 44 Definitions PDFDocument30 pagesSL20 The Proverb and Its 44 Definitions PDFbhuvaneswar ChilukuriNo ratings yet

- Suport Curs SemanticsDocument28 pagesSuport Curs SemanticsAlina MaisNo ratings yet

- Read The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic ScienceDocument3 pagesRead The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic SciencefytoxoNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Translation Studies: A reference volume for professional translators and M.A. studentsFrom EverandHandbook of Translation Studies: A reference volume for professional translators and M.A. studentsNo ratings yet

- Course Paper-AnaraDocument18 pagesCourse Paper-AnaraОрозбекова Нурзада КубанычбековнаNo ratings yet

- Contrastive Analysis of Idioms Expressing "Body Parts" in The English, Kyrgyz and Russian LanguagesDocument63 pagesContrastive Analysis of Idioms Expressing "Body Parts" in The English, Kyrgyz and Russian LanguagesMirlan Chekirov100% (10)

- Semantics and PragmaticsDocument39 pagesSemantics and PragmaticsAmyAideéGonzález100% (1)

- The Polysemy of Compound Words in Uzbek and EnglishDocument4 pagesThe Polysemy of Compound Words in Uzbek and EnglishResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Structural and Semantic Characteristics of Proverbs: Accepted25 November, 2021 & Published 30 November, 2021Document5 pagesStructural and Semantic Characteristics of Proverbs: Accepted25 November, 2021 & Published 30 November, 2021Eva EveNo ratings yet

- 01 Word PerfectDocument33 pages01 Word PerfectAlex RaducanNo ratings yet

- Assigment No 2: Semantics and Discourse Analysis CODE NO 557 Q1. Sense and ReferenceDocument5 pagesAssigment No 2: Semantics and Discourse Analysis CODE NO 557 Q1. Sense and ReferencefsdfsdfasdfasdsdNo ratings yet

- Ear Ir or o o A A I I Uea Ee EaDocument50 pagesEar Ir or o o A A I I Uea Ee EaLilit KarapetianNo ratings yet

- Linguistic modality in Shakespeare Troilus and Cressida: A casa studyFrom EverandLinguistic modality in Shakespeare Troilus and Cressida: A casa studyNo ratings yet

- Terex Rough Terrain Crane Rt555 2016 Workshop Manual Spare Parts SchematicsDocument22 pagesTerex Rough Terrain Crane Rt555 2016 Workshop Manual Spare Parts Schematicsbriansmith051291wkb100% (48)

- Adjective Clauses With Object PronounsDocument22 pagesAdjective Clauses With Object PronounsMike BojórquezNo ratings yet

- Kagawaran NG EdukasyonDocument4 pagesKagawaran NG Edukasyonjocelyn dianoNo ratings yet

- Look Forward: Home, and TheDocument10 pagesLook Forward: Home, and TheLiliya StoykovaNo ratings yet

- The Object of Study by Ferdinand de Saussure Summary (Critical Theory Third Semister)Document3 pagesThe Object of Study by Ferdinand de Saussure Summary (Critical Theory Third Semister)Nazer mirzaNo ratings yet

- Naoko Taguchi, Northern Arizona UniversityDocument61 pagesNaoko Taguchi, Northern Arizona UniversityNguyễn Hoàng Minh AnhNo ratings yet

- (AC-S09) Week 09 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz - INGLES IV (28880)Document4 pages(AC-S09) Week 09 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz - INGLES IV (28880)karina salazar huayascachiNo ratings yet

- FivparstrDocument2 pagesFivparstrjinlui chuahNo ratings yet

- CO2-lesson-plan English 4Document3 pagesCO2-lesson-plan English 4MIZLE PEROSONo ratings yet

- Tenses Review Bus 13 Unit 1Document3 pagesTenses Review Bus 13 Unit 1Daniel MartinezNo ratings yet

- Term Paper For Introduction To Language, Society, and CultureDocument5 pagesTerm Paper For Introduction To Language, Society, and CultureJR CortezNo ratings yet

- Unit Test 1: Answer All Thirty Questions. There Is One Mark Per QuestionDocument5 pagesUnit Test 1: Answer All Thirty Questions. There Is One Mark Per Questionazeneth santosNo ratings yet

- MTB 1 Lesson 1Document17 pagesMTB 1 Lesson 1Oscar Hogan BaldomeroNo ratings yet

- English Workbook Answers Stage 8Document37 pagesEnglish Workbook Answers Stage 8Ahmed Mostafa Lokman Mostafa Khattab67% (3)

- Writing Handout 4-5Document9 pagesWriting Handout 4-5Rosine ZgheibNo ratings yet

- Progress Test 12Document2 pagesProgress Test 12znghqxhrssNo ratings yet

- Quot English Quot Ingilis Dili Asas Xarici Dil Fanni Uzra 10 Cu Sinif Ucun Darslik 1539604664 369Document219 pagesQuot English Quot Ingilis Dili Asas Xarici Dil Fanni Uzra 10 Cu Sinif Ucun Darslik 1539604664 369East ofWestNo ratings yet

- Evaluación Diagnóstica: I-You - He - She - It - We - TheyDocument6 pagesEvaluación Diagnóstica: I-You - He - She - It - We - TheyJose Horacio RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Test 1 Translation WorkshopDocument2 pagesTest 1 Translation WorkshopyahirabdelNo ratings yet

- Reading and Writing Exercises Aug 27Document5 pagesReading and Writing Exercises Aug 27Vince pedrajaNo ratings yet

- 9 C Fce 13 UnitsDocument2 pages9 C Fce 13 UnitsCosmescu Mario FlorinNo ratings yet

- List of All Verbs For The JLPT n4 - Nihongo IchibanDocument9 pagesList of All Verbs For The JLPT n4 - Nihongo Ichibanryuuki09100% (1)

- Simcat 4 Experts ' TakeDocument6 pagesSimcat 4 Experts ' TakeKetan MNo ratings yet

- EXERCISEDocument3 pagesEXERCISERiska Nahara SaputriNo ratings yet

- To Get To Know The Project, Sequence and The Vocabulary They Need During The Current SequenceDocument2 pagesTo Get To Know The Project, Sequence and The Vocabulary They Need During The Current Sequenceyounes keraghelNo ratings yet

- 94 - Modal VerbsDocument21 pages94 - Modal VerbsAurora AmadoNo ratings yet

- BI Y2 LP TS25 (Unit 5 LP 1-25)Document27 pagesBI Y2 LP TS25 (Unit 5 LP 1-25)Mai Abd HamidNo ratings yet

- Grammar 4 (Adjectives and Adverbs)Document20 pagesGrammar 4 (Adjectives and Adverbs)M Dwi RafkyNo ratings yet

- Be Careful of Present ParticipleDocument14 pagesBe Careful of Present Participlemuhamad akrom hasaniNo ratings yet

- Class Ii - Simple PastDocument7 pagesClass Ii - Simple PastLeydi Manay CadenaNo ratings yet