Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Long Range Effect of Sleep On Retention

Uploaded by

Aldrien0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views5 pagesThis study tested the hypothesis that retention of nonsense syllables is greater when learning is followed by 8 hours of sleep rather than 8 hours of waking activities, at intervals of 24, 48, and 144 hours. 18 male university students learned and recalled 6 lists of 10 nonsense syllables under both sleep and waking conditions. The results supported the hypothesis at the 144-hour interval, showing significantly better retention after sleep, but found no significant differences at 24 and 48 hours. The roles of memory consolidation and interference are discussed, and need for further research on the critical period for consolidation.

Original Description:

Original Title

The long range effect of sleep on retention

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis study tested the hypothesis that retention of nonsense syllables is greater when learning is followed by 8 hours of sleep rather than 8 hours of waking activities, at intervals of 24, 48, and 144 hours. 18 male university students learned and recalled 6 lists of 10 nonsense syllables under both sleep and waking conditions. The results supported the hypothesis at the 144-hour interval, showing significantly better retention after sleep, but found no significant differences at 24 and 48 hours. The roles of memory consolidation and interference are discussed, and need for further research on the critical period for consolidation.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views5 pagesThe Long Range Effect of Sleep On Retention

Uploaded by

AldrienThis study tested the hypothesis that retention of nonsense syllables is greater when learning is followed by 8 hours of sleep rather than 8 hours of waking activities, at intervals of 24, 48, and 144 hours. 18 male university students learned and recalled 6 lists of 10 nonsense syllables under both sleep and waking conditions. The results supported the hypothesis at the 144-hour interval, showing significantly better retention after sleep, but found no significant differences at 24 and 48 hours. The roles of memory consolidation and interference are discussed, and need for further research on the critical period for consolidation.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Australian Journal of Psychology

Vol. 15, No. I, 1963

THE LONG RANGE EFFECT OF SLEEP

ON RETENTION

ALAN RICHARDSON and JOHN ERIC GOUGH

University of Western Australia

A test is made of the hypothesis that a greater number of nonsense

syllables will be retained after intervals of 24, 48 and 144 hours when

learning is followed immediately by 8 hours sleep than when learning

is followed by normal waking activities. The results for the 144-hour

interval support the hypothesis at the #<-or level of confidence but the

differences at 48 and 24 hours are decreasing and insignificant. The possible

roles of consolidation and interference are discussed and the need for

further research into the critical period necessary for consolidation to

occur is emphasized.

Since the pioneer investigations of hours there was a statistically signi-

Heine (1914) and of Jenkins and cant difference in favour of the

Dallenbach (1924) there have been sleep condition (pc.01). However

several important studies reporting this experiment is open to criticism

the effect of sleep on retention (Dahl, on the grounds that the experimen-

1928; van Ormer, 1932; Newman, ter was her own S and no controlled

1939; Minami & Dallenbach, 1946). method of presenting the nonsense

The evidence is fairly clear, at least syllables was employed. In a more

for nonsense syllables, that when adequately controlled experiment,

learning is immediately followed by Gibb (1937) used six Ss and

8 hours sleep less is forgotten than measured retention by the savings

when learning is immediately fol- method after intervals of 24, 48, 72

lowed by an equivalent period of and 96 hours. Each S had two ex-

waking activity. The advantage of perimental sessions for each time in-

the sleep condition over the waking terval and under both sleep and

is apparent after 2 to 4 hours sleep waking conditions. The results of

and this advantage typically in- this study showed an insignificant

creases to a maximum after an inter- difference in favour of the waking

val of 8 hours sleep. condition for the 24 hour interval, a

Two other studies which have re- highly significant difference in

ceived scant recognition in the gen- favour of the sleep condition for the

eral literature on memory processes 48 hour interval (p<-or) and insig-

have been concerned with the rela- nificant and decreasing differences in

tively long range effects of sleep on favour of sleep after intervals of 72

retention. Graves ( I 937) used herself and 96 hours.

as a subject and tested retention by Criticism of the Gibb experiment

the savings method. She found that may be made on three counts. As

for a 24 or 48 hour interval there the Ss relearned an old list and then

was an insignificant difference in learned a new list in most experi-

favour of the waking condition, but mental sessions it is difficult to assess

that for intervals of 72, 96 and 144 the extent of interference effects. In

37

38 Alan Richardson and John Eric Gough

at least one of the learning sessions of them reported that they were

a room-mate of one of the students normally asleep soon after mid-

was present. Ss were allowed to sleep night.

during the day if they wished.

The general purpose of the pre- Task

sent study is to provide further evi- Six lists of 10 three-letter non-

dence for or against the hypothesis sense syllables were constructed on

that sleep following learning has ad- the basis of lists reported by Hilgard

vantageous long range effects on re- (I 951). The average association

tention. values of the 6 lists ranged from

The specific hypothesis to be 22.7 to 27.3.

tested may be stated as follows : that

a greater number of nonsense syll-

Apparatus

ables will be retained after intervals

of 24,48 and 144hours when learn- An electrically operated memory

ing is followed immediately by 8 drum of local design was used to

hours sleep than when learning is present the syllables. Each syllable

followed by normal waking ac- was exposed for I -6secs with an in-

tivities. terval of 5-5 secs before the list was

repeated. Only one list was learned

METHOD in each experimental session. The

Subjects criterion for both learning and re-

I 8 male university students hav-

learning was three successive error-

ing a mean age of 1 9 years served less repetitions. No practice trials

as Ss. All were residents at a Roman were given and the method of serial

Catholic Residential College and all anticipation was employed.

but five of them were first year

students. Procedure

Scores on the A.C.E.R. B4o intelli- The morning and evening trials

gence test and on the Cattell 16PF were arranged on the basis of each

test were available for most Ss. The S’s typical waking and retiring time.

mean I.Q. was 124and no marked Three times were selected for morn-

deviations from normal were found ing trials: 7.30, 7.50 and 8.10,and

on the 16 PF test. A 43-item pre- for the evening trials I 1.20, 11.40

experimental interview schedule and 1 2 midnight. Those S s who re-

was used to investigate typical tired latest usually rose latest and

weekly timetables, daily routines, vice versa, thus making it possible

sleeping habits and so on. to arrange them in groups of three

All Ss claimed to have no diffi- so that their experimental sessions

culty in going to sleep, their esti- synchronized fairly well with their

mates ranging from 5 to 20 minutes. sleeping habits. For the evening

All claimed to be reasonably sound trials each S had to be completely

sleepers and to be well adapted to ready for bed including final toilet-

the typical noises associated with life ing and devotional exercises. When

in a residential college. Waking in the learning or relearning trials had

the morning for these Ss varied been completed the S immediately

from 7 o’clock to 8 o’clock and most got into bed and the experimenter

The L o n g Range Eflect of Sleep o n Retention 39

turned out the light before leaving Though each S knew from the be-

the room. ginning of the study the dates and

A partially balanced design was times on which his experimental

used in which each S had a total of sessions would fall, no information

1 2 sessions. Each of the 18 Ss was was given as to which would be a

tested for retention under sleeping learning session and which a re-

and waking conditions for each in- learning.

terval. The schedule used with the The problem of rehearsal has been

first 6 Ss (A to F) is shown in Table I present in all studies of this kind

and was repeated with Ss G to L and and the only control employed has

M to R. The whole pattern was re- been verbal instruction by the ex-

peated for the relearning situation. perimenter not to rehearse or to dis-

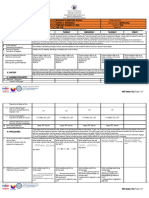

TABLE

I

Simple Testing Schedule

Subject

A B C D E F

24s '44W 24W 144s 48W

24W '44s 48W

48s 24s '44W 48s

48W 24s '44W z4W 144s

24w 144s '44W

48s

144s 48W 24s I44W 24w

'44W 48s 24w 144s 48W 24s

As no significant diurnal varia- cuss. This method was employed in

tion in learning efficiency was found the present investigation. In the

for any of the Ss no correction for post-experimental interview all Ss

this potential source of bias was affirmed that they had not rehearsed

necessary. The mean number of the syllables. All Ss reported slight

trials required to learn lists in the but very general discussion of the

evening was 20-7 compared with a experiment but none of them had

mean of 20.5 for the morning guessed its purpose and no details

sessions. were discussed by any S .

There were no significant differ-

RESULTS

ences in the difficulty level of the

six lists used, nor were any signifi- The significance of the difference

cant practice effects obtained. between the group mean scores for

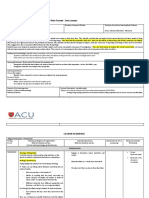

TABLE

2

Means, standard deviations and tests for the significance of the differences

between mean group saving scores (in percentages) for sleep and waking

conditions for each time interval

-~ ~

24 hours 48 hours 144 h w r s

Sleep Waking Sleep Waking Sleep Waking

Means 77.30 78.40 77-70 73.20 71'40 55-50

S.DS 12.87 909 9-96 13.88 11-32 1599

t 0'32 1-46 3'45

PC 080 020 0'01

40 Alan Richardson and ]ohn Eric Gough

the sleep and waking conditions was can be invoked to account for the

tested for each time interval using long term benefits of the sleep con-

the t test for means of related dition where the actual amount of

samples. time spent in sleeping and waking

The results summarized in Table 2 is the same. Under these conditions

provide partial support for the hypo- the opportunity for waking activity

thesis. A significant difference in to interfere with original learning is

favour of the sleep condition was equal and an explanation in terms of

found for the 144 hour interval interference alone would appear to

(pc-or).For the 48 hour interval an be inadeqate. However, it should

insignificant difference was obtained be noted that the equivocal results at

in favour of the sleep condition and 24 and 48 hours cannot be explained

for the 24 hour interval an insignifi- by either hypothesis.

cant difference was found in favour Though the evidence for the exis-

of the waking condition. tence of a consolidation process has

been considered inadequate in the

DISCUSSION

past, a recent review of the literature

These results provide some sup- by Glickman ( I 961) concludes, “the

port for the conclusions of previous overall weight of evidence certainly

investigators. If learning is followed favours the existence of some mech-

immediately by a period of approxi- anism of consolidation (in spite of

mately 8 hours sleep, retention at the fact that alternative explana-

the end of I++ hours will be superior tions are possible for many of the

to learning that is followed by wak- experiments which supposedly sup-

ing activities. Evidence from this ex- port the existence of such a pro-

periment is equivocal for the two cess).”

shorter intervals. From the behavioural evidence in

Assuming that the trend revealed this and related studies and from

in this and the two previous studies the neuro-physiological evidence

(Graves, 1937; Gibb, 1937) is not an cited by Glickman (1961)further re-

experimental artifact the question search on the concept of consolida-

must be asked as to why the pres- tion appears desirable. For the psy-

ence or absence of 8 hours sleep chologist one of the most obvious

immediately after learning should lines of enquiry is to obtain a more

in general aid the retention of non- exact knowledge of the critical

sense syllables over periods of up to period within which minimal inter-

I 44 hours. ference is essential if consolidation

The two related hypotheses that of the memory trace is to take place.

have been invoked most frequently

in an attempt to account for the REFERENCES

advantage of the sleep condition

have been consolidation and inter- DAHL, A. ( I 928). In van Ormer, E. B.,

ference (van Ormer, 1933). The in- Sleep and retention. Psychol.

terference hypothesis has usually Bull., 1933, 30,4’5-439.

been offered as an explanation of the GIBB, J. R. The relative effects of

slower rate of forgetting during sleep sleep and waking upon the reten-

while the consolidation hypothesis tion of nonsense syllables, Un-

The Long Range Eflect of Sleep on Retention 4'

published M.A. thesis, Brigham Obliviscence during sleep and

Young Univer., 1937. (Microfilm.) waking. Amer. J . Psychot., I 924,

GLICKMAN, S. E. Perseverative neural 35, 605-612.

processes and consolidation of the MINAMI, H., & DALLENBACH, K. M.

memory trace. Psychol. Bull., The effect of activity upon learn-

1961,58, 218-233. ing and retention in the cock-

GRAVES, E. A. The effect of sleep up- roach. Amer. J . Psychol, 1946, 59,

on retention. ]. exp. Psychol., I -58.

1937, 19,316-322. NEWMAN, E. B. Forgetting of mean-

HEINE,R. (1914). In van Ormer, ingful material during sleep and

E. B., Sleep and retention. Psy- waking. Amer. J . Psychol., I 939,

chol. Bull., I 933, 30, 41 5-439. 52, 65-71.

HILGARD, E. R. Methods and Pro- VANORMER, E. G. Retention after

cedures in the study of learning. intervals of sleep and waking.

In Stevens, S. S. (Ed.) Handbook Arch. Psychot., 1932, N.Y.: 137.

of ex perimen to2 psycho logy, VANORMER, E. G. Sleep and reten-

N.Y.: Wiley, 1951. tion. Psychol. Bull., 1933, 30, 415-

JENKINS, J. B. & DALLENBACH, K. M. 439.

(Manuscript received 6 December 1961)

You might also like

- Psychobiology of Stress: A Study of Coping MenFrom EverandPsychobiology of Stress: A Study of Coping MenHolger UrsinNo ratings yet

- Parallel Brain Systems For Learning With and Without AwarenessDocument14 pagesParallel Brain Systems For Learning With and Without Awarenessdsekulic_1No ratings yet

- The Kybernetics of Natural Systems: A Study in Patterns of ControlFrom EverandThe Kybernetics of Natural Systems: A Study in Patterns of ControlNo ratings yet

- Supplementary Information Supplementary Methods and Results: 1 Subjects, Procedure, and Memory TasksDocument12 pagesSupplementary Information Supplementary Methods and Results: 1 Subjects, Procedure, and Memory TasksVlad PredaNo ratings yet

- Sleep Patterns Following 205 Hours of Sleep DeprivationDocument12 pagesSleep Patterns Following 205 Hours of Sleep DeprivationShoaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Sleep Loss On Component Movements of Human MotionDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Sleep Loss On Component Movements of Human MotionmcwnotesNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Insomnia by Paradoxical Intention: A Time-Series AnalysisDocument5 pagesTreatment of Insomnia by Paradoxical Intention: A Time-Series AnalysisVASCHOTI TRABANICONo ratings yet

- bf0066311120161008 9678 Odic61 With Cover Page v2Document18 pagesbf0066311120161008 9678 Odic61 With Cover Page v2Jomari Daño PascualNo ratings yet

- SleepDocument8 pagesSleepHomunculus 4madeusNo ratings yet

- Learn. Mem.-2010-Broadbent-5-11SEminario 2013Document8 pagesLearn. Mem.-2010-Broadbent-5-11SEminario 2013Hamlet666No ratings yet

- The Standard 1-Hour Pad Test: Does It Have Any Value in Clinical Practice?Document4 pagesThe Standard 1-Hour Pad Test: Does It Have Any Value in Clinical Practice?Puspitasari NotohatmodjoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Discimination Training On Auditory Generalization - Jenkins & HarrisonDocument8 pagesEffect of Discimination Training On Auditory Generalization - Jenkins & HarrisonjsaccuzzoNo ratings yet

- Torbjorn Erstedt KEN Hume: Perceptual and Motor SkillsDocument10 pagesTorbjorn Erstedt KEN Hume: Perceptual and Motor SkillsGonzalo Blanco RubinaNo ratings yet

- 1986rWetzlerNebes ChapinAM AcrossLifespanDocument22 pages1986rWetzlerNebes ChapinAM AcrossLifespanЮлия ЗинченкоNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Duration of Post Traumatic AmnesiaDocument4 pagesMeasuring The Duration of Post Traumatic AmnesiaAnonymous R6ex8BM0No ratings yet

- Strogatz JTheorBiolDocument21 pagesStrogatz JTheorBiolSamuearlNo ratings yet

- Use of Imagery in Psychokinesis Research by Michael Nanko PHDDocument7 pagesUse of Imagery in Psychokinesis Research by Michael Nanko PHDMichael Nanko100% (2)

- Coospace 14Document4 pagesCoospace 14KamillaJuhászNo ratings yet

- Gibbon 1977Document21 pagesGibbon 1977yom.moguelNo ratings yet

- 10 1093@sleep@26 2 117Document11 pages10 1093@sleep@26 2 117Intan AyueNo ratings yet

- Age-Related Differences For Duration Discrimination in RatsDocument4 pagesAge-Related Differences For Duration Discrimination in RatsjsaccuzzoNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Serial and Free Recall: Brandeis University, Waltham, MassachusettsDocument7 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Serial and Free Recall: Brandeis University, Waltham, MassachusettsAnn ChristineNo ratings yet

- Sleep 26 2 117Document10 pagesSleep 26 2 117ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Gais04 PDFDocument5 pagesGais04 PDFidjacobsNo ratings yet

- Glenn Legault Et Al - Scopolamine During The Paradoxical Sleep Window Impairs Radial Arm Maze Learning in RatsDocument7 pagesGlenn Legault Et Al - Scopolamine During The Paradoxical Sleep Window Impairs Radial Arm Maze Learning in RatsHumiopNo ratings yet

- Sleep Study Student Experiment ReportDocument9 pagesSleep Study Student Experiment Reporthsheepie4No ratings yet

- Research Findings and DiscussionsDocument15 pagesResearch Findings and DiscussionsFila DataSquareNo ratings yet

- Brit J Clinical Pharma - October 1996 - KEECH - Absence of Effects of Prolonged Simvastatin Therapy On Nocturnal Sleep in ADocument8 pagesBrit J Clinical Pharma - October 1996 - KEECH - Absence of Effects of Prolonged Simvastatin Therapy On Nocturnal Sleep in AFirmansyah LatiefNo ratings yet

- Sleep Quality Subtypes in Midlife Women PDFDocument6 pagesSleep Quality Subtypes in Midlife Women PDFJuhari Yusuf FatahillahNo ratings yet

- Pearce, Redhead, Aydin (1997)Document22 pagesPearce, Redhead, Aydin (1997)Dagon EscarabajoNo ratings yet

- Biological Approach Case StudiesDocument6 pagesBiological Approach Case Studieskrystlemarley125No ratings yet

- Jurnal RelaksasiDocument9 pagesJurnal Relaksasiasyfah 07No ratings yet

- Hovland 1937 IVDocument16 pagesHovland 1937 IVjsaccuzzoNo ratings yet

- An Experimental Paper and Pencil Test For Assessing Ego StatesDocument5 pagesAn Experimental Paper and Pencil Test For Assessing Ego StatesNarcis NagyNo ratings yet

- Lab 601 Group 1Document13 pagesLab 601 Group 1Clemente Abines IIINo ratings yet

- Successive Matching-To-Sample in The Pigeon: Variations On A Theme by KonorskiDocument5 pagesSuccessive Matching-To-Sample in The Pigeon: Variations On A Theme by KonorskikarNo ratings yet

- Askew (1970)Document6 pagesAskew (1970)Jorge PintoNo ratings yet

- Working Memory in Clinical Depression: An Experimental StudyDocument5 pagesWorking Memory in Clinical Depression: An Experimental StudysamiNo ratings yet

- Retention of A Light-Dark Discrimination in Rats of Different AgesDocument6 pagesRetention of A Light-Dark Discrimination in Rats of Different AgesAliNo ratings yet

- Autobiographical Memory in AmnesiaDocument11 pagesAutobiographical Memory in AmnesiaCarlosNo ratings yet

- Universite: Rate)Document13 pagesUniversite: Rate)José HernándezNo ratings yet

- 2001 The First-Night Effect May Last More Than One NightDocument8 pages2001 The First-Night Effect May Last More Than One NightpsicosmosNo ratings yet

- Tolerance To Shift Work: A Chronobiological ApproachDocument13 pagesTolerance To Shift Work: A Chronobiological ApproachAnastasiya PhilippeNo ratings yet

- Locus of Control in Short and Long SleepersDocument2 pagesLocus of Control in Short and Long Sleepersapi-3731512No ratings yet

- Morningness-Eveningness QuestionnaireDocument4 pagesMorningness-Eveningness QuestionnaireSyeda RaihaNo ratings yet

- Maternity Blues: II. A Comparison Between Post-Operative Women and Post-Natal WomenDocument4 pagesMaternity Blues: II. A Comparison Between Post-Operative Women and Post-Natal WomenParamita Angkin SaputriNo ratings yet

- MCS M-SC: .77) .77) .77) .88) .75) - A Cluster Analysis Yielded Two Clusters, With The Three CollegeDocument2 pagesMCS M-SC: .77) .77) .77) .88) .75) - A Cluster Analysis Yielded Two Clusters, With The Three CollegeKRUNAL ParmarNo ratings yet

- Research Submission: 24-Hour Distribution of Migraine AttacksDocument6 pagesResearch Submission: 24-Hour Distribution of Migraine AttacksOlli OppilasNo ratings yet

- Malmo 1960Document24 pagesMalmo 1960Víctor FuentesNo ratings yet

- Wiley, Society For Research in Child Development Child DevelopmentDocument7 pagesWiley, Society For Research in Child Development Child DevelopmentVíctor FuentesNo ratings yet

- Subjective Ratings of Sleepiness-The Underlying Circadian MechanismsDocument11 pagesSubjective Ratings of Sleepiness-The Underlying Circadian MechanismsPriyanka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Studying in The Afternoon Is Best (This Is The Study That Proves It)Document5 pagesStudying in The Afternoon Is Best (This Is The Study That Proves It)melissayplNo ratings yet

- L5 HearstConcuGenerGradients ConAlimentoVsChoqueDocument13 pagesL5 HearstConcuGenerGradients ConAlimentoVsChoqueIzra ContrerasNo ratings yet

- HL - Chronic Effects of Brahmi (Bacopa Monnieri) On Human MemoryDocument3 pagesHL - Chronic Effects of Brahmi (Bacopa Monnieri) On Human Memory1mcryptocapitalNo ratings yet

- Tmp3e00 TMPDocument6 pagesTmp3e00 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Feedback Maintained Reinforcement': University of Wisconsin-MilwaukeeDocument12 pagesFeedback Maintained Reinforcement': University of Wisconsin-MilwaukeeVladimir RuizNo ratings yet

- One Bar-Press Per DayDocument5 pagesOne Bar-Press Per DayALEJANDRO MATUTENo ratings yet

- Ince, L. P. (1968) - Modification of Verbal Behavior Through Variable Interval Reinforcement in A Quasi-Therapy Situation.Document7 pagesInce, L. P. (1968) - Modification of Verbal Behavior Through Variable Interval Reinforcement in A Quasi-Therapy Situation.Gabriel Fernandes Camargo RosaNo ratings yet

- An Experimental Study of Related Processes in Span of Attention and in PerceptionDocument71 pagesAn Experimental Study of Related Processes in Span of Attention and in PerceptionTapaswiniNo ratings yet

- EMG Biofeedback and The Treatment of Tension Headaches A Systematic Analysis of Treatment ComponentsDocument12 pagesEMG Biofeedback and The Treatment of Tension Headaches A Systematic Analysis of Treatment ComponentsStéfanie PaesNo ratings yet

- 3072 - Cfe - 106B - Toralba, Aldrien E. - Journal #2Document1 page3072 - Cfe - 106B - Toralba, Aldrien E. - Journal #2AldrienNo ratings yet

- Bioethanol New Opportunities For An Ancient ProductDocument34 pagesBioethanol New Opportunities For An Ancient ProductAldrienNo ratings yet

- Response Surface Methodology A RetrospectiveDocument26 pagesResponse Surface Methodology A RetrospectiveAldrienNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Daily Sleep Duration On HealthDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Daily Sleep Duration On HealthAldrienNo ratings yet

- Metabolic Consequences of Sleep and Sleep LossDocument6 pagesMetabolic Consequences of Sleep and Sleep LossAldrienNo ratings yet

- Recent Trends in The Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass For Value-Added ProductsDocument74 pagesRecent Trends in The Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass For Value-Added ProductsAldrienNo ratings yet

- Multivariate Data Analysis Applied in Alkali-Based Pretreatment of Corn StoverDocument12 pagesMultivariate Data Analysis Applied in Alkali-Based Pretreatment of Corn StoverAldrienNo ratings yet

- ZeoliteDocument29 pagesZeoliteAldrienNo ratings yet

- Hypoglycemia Low Blood Sugar in AdultsDocument1 pageHypoglycemia Low Blood Sugar in AdultsAldrienNo ratings yet

- Physicochemical Characterization, Modelling and Optimization ofDocument13 pagesPhysicochemical Characterization, Modelling and Optimization ofAldrienNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Tax DeclarationDocument1 pageTransfer of Tax DeclarationAldrienNo ratings yet

- LegacyDocument2 pagesLegacyAldrienNo ratings yet

- Age Is Not A LimitDocument1 pageAge Is Not A LimitAldrienNo ratings yet

- Myths vs. Facts About CounselingDocument2 pagesMyths vs. Facts About CounselingMaria MagdalenaNo ratings yet

- Phrasal Verb Mix and Match: Connect Verbs DefinitionDocument9 pagesPhrasal Verb Mix and Match: Connect Verbs Definitionინგლისურის გზამკვლევიNo ratings yet

- AIexplain AIDocument8 pagesAIexplain AIFathima HeeraNo ratings yet

- Ethical Leadership Psychology Decision Making PDFDocument2 pagesEthical Leadership Psychology Decision Making PDFPierre0% (1)

- Accomplishment Report For Remediation S.Y. 2021 2022Document4 pagesAccomplishment Report For Remediation S.Y. 2021 2022johayma fernandez100% (1)

- Nursing SopDocument3 pagesNursing SopChelsy Sky SacanNo ratings yet

- The History and Development of Applications in Artificial Intelligence Before The 21st CenturyDocument15 pagesThe History and Development of Applications in Artificial Intelligence Before The 21st CenturyMohammad AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Building Blocks QuestionnaireDocument7 pagesBuilding Blocks Questionnairenadila mutiaraNo ratings yet

- 1 - PGDE - Educational Psychology ApplicationDocument7 pages1 - PGDE - Educational Psychology ApplicationatiqahNo ratings yet

- Spoken Word Poetry Year 9 Task Name: Myself, My Whanau, Where I Am From, and Where I Am Going ToDocument2 pagesSpoken Word Poetry Year 9 Task Name: Myself, My Whanau, Where I Am From, and Where I Am Going ToSitty Aizah MangotaraNo ratings yet

- Conflict ResolutionDocument8 pagesConflict Resolutionbrsiwal1475100% (1)

- Dyscalculia (Math)Document14 pagesDyscalculia (Math)David Montiel RamirezNo ratings yet

- Test Review: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals - Fifth Edition (CELF-5)Document20 pagesTest Review: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals - Fifth Edition (CELF-5)Manali SelfNo ratings yet

- Power Intention (Christallin Command) : CROWN HEART INTEGRATION (Aligning Head and Heart)Document1 pagePower Intention (Christallin Command) : CROWN HEART INTEGRATION (Aligning Head and Heart)Rutger ThielenNo ratings yet

- Abundant Thinking - Achieving The Rich Dad MindsetDocument19 pagesAbundant Thinking - Achieving The Rich Dad MindsetJuanesVasco100% (2)

- DLL Arts Q3 W5Document7 pagesDLL Arts Q3 W5Cherry Cervantes HernandezNo ratings yet

- CAE - Unit 7 - 8 ReviewDocument9 pagesCAE - Unit 7 - 8 ReviewJessica Pimentel0% (1)

- Generative AI Opportunity of A LifetimeDocument3 pagesGenerative AI Opportunity of A Lifetimeshubhanwita2021oacNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Lesson PlanDocument18 pagesMulticultural Lesson Planapi-610733534No ratings yet

- Hugot in The Millenial EraDocument7 pagesHugot in The Millenial EraDaine CandoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Sound Around UsDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Sound Around UsHasif Arsyad Hassan AdliNo ratings yet

- NEW YEAR FINAL LESSON PLAN IN ENGLISH 2nd GradeDocument3 pagesNEW YEAR FINAL LESSON PLAN IN ENGLISH 2nd GradeMiss LeighhNo ratings yet

- 3.detailed Lesson Plan in English 3 q1Document2 pages3.detailed Lesson Plan in English 3 q1Leslie Peritos100% (2)

- Functional Harmony - AgmonDocument20 pagesFunctional Harmony - AgmonsolitasolfaNo ratings yet

- KRR Lecture 1 Intro FOPLDocument34 pagesKRR Lecture 1 Intro FOPLMihaela CulcusNo ratings yet

- Phonemes Distinctive Features Syllables Sapa6Document23 pagesPhonemes Distinctive Features Syllables Sapa6marianabotnaru26No ratings yet

- Adjective SuffixesDocument4 pagesAdjective SuffixeshandiloreaNo ratings yet

- All Rights Reserved. This Thesis May Not Be Reproduced in Whole or in Part by Mimeograph or Other Means Without The Permission of The AuthorDocument219 pagesAll Rights Reserved. This Thesis May Not Be Reproduced in Whole or in Part by Mimeograph or Other Means Without The Permission of The AuthorGeNo ratings yet

- Simple Present PracticaDocument2 pagesSimple Present PracticaEricka María Hernández de Quintana100% (1)

- Victorian Curriculum Overview and Lesson Plan Format - One LessonDocument6 pagesVictorian Curriculum Overview and Lesson Plan Format - One Lessonapi-611920958No ratings yet