Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sahani 2013

Uploaded by

Patricia BezneaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sahani 2013

Uploaded by

Patricia BezneaCopyright:

Available Formats

G a s t r o i n t e s t i n a l I m a g i n g • B e s t P r a c t i c e s / R ev i ew

Sahani et al.

Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

Gastrointestinal Imaging

Best Practices/Review

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Diagnosis and Management

of Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

Dushyant V. Sahani1 OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this review is to outline the management guidelines for the

Avinash Kambadakone1 care of patients with cystic pancreatic lesions.

Michael Macari2 CONCLUSION. The guidelines are as follows: Annual imaging surveillance is gener-

Noaki Takahashi 3 ally sufficient for benign serous cystadenomas smaller than 4 cm and for asymptomatic le-

Suresh Chari 4 sions. Asymptomatic thin-walled unilocular cystic lesions smaller than 3 cm or side-branch

intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms should be followed up with CT or MRI at 6 and

Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo 5

12 months interval after detection. Cystic lesions with more complex features or with growth

Sahani DV, Kambadakone A, Macari M, Takahashi rates greater than 1 cm/year should be followed more closely or recommended for resection if

N, Chari S, Fernandez–del Castillo C the patient’s condition allows surgery. Symptomatic cystic lesions, neoplasms with high ma-

lignant potential, and lesions larger than 3 cm should be referred for surgical evaluation. En-

doscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy can be used preoperatively to

assess the risk of malignancy.

Clinical Vignettes and Images ing inflammatory (pseudocysts), benign (serous

The increasing use and improved spatial cystadenomas), precancerous (intraductal pap-

and contrast resolution of advanced cross- illary mucinous neoplasms [IPMNs] and mu-

sectional imaging techniques such as MDCT cinous cystic neoplasms [MCNs]), and frank-

and MRI have resulted in a marked increase ly malignant (cystadenocarcinomas) [8–12].

Keywords: cystic pancreatic lesion, MDCT, MRI

in the incidental detection of cystic pancreat- Cystic pancreatic lesions not only have di-

DOI:10.2214/AJR.12.8862 ic lesions. They are encountered in as many verse histologic and imaging appearances but

as 2.6% of abdominal MDCT examinations also differ in clinical presentation, biologic be-

Received February 25, 2012; accepted after revision and 20% of MRI studies [1–3]. Larger cystic havior, growth pattern, and risk of malignan-

July 18, 2012. pancreatic lesions are typically symptomat- cy (Table 1). Accurate risk stratification and

1

Department of Radiology, Division of Abdominal

ic, and incidentally detected cystic pancreat- decisions on treatment and follow-up strate-

Imaging and Intervention, Massachusetts General ic lesions are often small. Increased identifi- gy necessitate precise lesion characterization

Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 55 Fruit St, White 270, cation of cystic pancreatic lesions at MDCT and diagnosis [2, 13–16]. The current manage-

Boston, MA 02114. Address correspondence to and MRI presents a clinical conundrum for ment of common cystic pancreatic lesions is

D. V. Sahani (dsahani@partners.org).

appropriate further management [4–7]. Ac- summarized in Table 2.

2

Department of Radiology, Division of Abdominal curate characterization of these cystic le-

Imaging, New York University Langone Medical Center, sions is essential for further management, Synopsis and Synthesis of Evidence

New York, NY. either surgical or conservative. In a select The most common nonneoplastic cystic pan-

3

group of patients, endoscopic ultrasound and creatic lesions are pseudocysts, which usually

Department of Radiology, Division of Abdominal

Imaging, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

cyst aspiration can be performed for further arise as a sequela of pancreatitis or trauma. The

characterization. Clinical vignettes are pre- most common cystic pancreatic neoplasms

4

Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, sented in Figures 1–4. are IPMNs, MCNs, and serous cystadenomas

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. (SCAs) [12, 17–20]. Although SCAs and

5 The Imaging Question pseudocysts are considered benign, IPMNs and

Department of Surgery, Division of Pancreatic Surgery,

Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical How do we characterize, diagnose, and ap- MCNs have malignant potential [19, 21–23].

School, Boston, MA. propriately manage incidentally found cystic Other cystic pancreatic lesions account for few-

pancreatic lesions? er than 10% of cases and include uncommon

AJR 2013; 200:343–354 pathologic findings such as solid pseudopap-

0361–803X/13/2002–343

Background and Importance illary neoplasms, cystic pancreatic neuroen-

Cystic pancreatic lesions encompass a var- docrine neoplasms, cystic degeneration in other

© American Roentgen Ray Society ied group of pancreatic abnormalities, includ- solid pancreatic neoplasms, lymphoepithelial

AJR:200, February 2013 343

Sahani et al.

cysts, and cystic adenocarcinoma of the pan- MDCT 58 histopathologically proven cystic pancre-

creas [5, 24, 25]. MDCT is the primary modality for imaging atic masses. In a study of 100 cystic pancre-

of cystic pancreatic lesions, including IPMNs, atic lesions, Chaudhari and colleagues [32,

Diagnosis owing to its high spatial and temporal resolu- 33] reported an accuracy of 71–79% for

Imaging plays a crucial role in the man- tion, speed of acquisition, wide availability, MDCT for discriminating premalignant or

agement of cystic lesions of the pancreas, and ease of interpretation [2, 15, 16, 28]. The malignant lesions from benign lesions. Lee

including lesion detection and character- superior quality of 2D and 3D image displays et al. [2] reported a comparable accuracy

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

ization. Technologic innovations in MDCT generated from isotropic MDCT datasets has (63.9–73.5%) of MDCT for differentiating

and MRI have led to improvement in anal- facilitated excellent depiction of the detailed benign from malignant cystic pancreatic le-

ysis and morphologic differentiation of cys- regional pancreatic anatomy and precise def- sions. However, subclassification of cystic

tic pancreatic lesions and are widely consid- inition of the morphologic characteristics of lesions into histopathologic types is often

ered the primary imaging modalities in the cysts [26, 29, 30]. Image postprocessing in a difficult because of overlapping imaging fea-

care of patients with cystic lesions of the desired plane also allows determination of the tures. Increasingly, the morphologic pattern

pancreas. In addition, advances in postpro- communication between the cystic lesion and depicted on MDCT images is being used to

cessing have enabled enhanced definition of the main pancreatic duct, a key feature in the categorize cystic pancreatic lesions broadly

the extent of a lesion and its relation to ad- diagnosis of side-branch IPMNs [26]. Howev- into mucinous and nonmucinous types and

jacent structures. These techniques are par- er, the presence of a small duct or a collapsed then subdivide them on the basis of complex

ticularly valuable in delineating the relation duct can impede visualization of ductal com- features into aggressive and nonaggressive

between the cystic lesion and the pancreat- munications [26]. lesions [2, 15, 22]. In a study of 114 patients

ic duct, a key feature in differentiating side- MDCT has a reported accuracy of 56– with 130 cystic pancreatic lesions, Sahani

branch IPMNs from other cystic lesions [24, 85% for characterization of cystic pancreatic and colleagues [15] stratified the lesions into

26, 27]. The following imaging modalities lesions, which is comparable to that of MRI mucinous and nonmucinous subtypes with

can be used either independently or in com- [2, 15, 16, 28, 31]. Visser et al. [30] found an accuracy of 82–85% and reported an ac-

bination to help in the diagnosis and manage- that MDCT had an accuracy of 76–82% in curacy of 85–86% for recognizing aggres-

ment of cystic pancreatic lesions. establishing the diagnosis of malignancy in sive biologic features. Similar accuracy has

Fig. 1—MDCT images in four patients with incidental

finding of pancreatic cystic lesion.

A, 62-year-old-man with 1.2-cm cystic lesion (arrow)

in pancreatic body without main pancreatic ductal

dilatation or enhancing solid components. Coronal

MDCT image shows main pancreatic duct intimately

associated with cystic lesion, and communication

between cystic lesion and main duct is evident.

Lesion is typical of nonaggressive side branch

intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm that does

not warrant surgical resection.

B, 69-year-old woman with cystic lesion in pancreatic

tail. Axial MDCT image shows cystic lesion in

pancreatic tail (white arrows) with enhancing

A B solid components (black arrow) and peripheral rim

calcification. Findings are indicative of aggressive

mucinous cystic lesion. Patient underwent distal

pancreatectomy, and histopathologic examination

revealed mucinous cystadenocarcinoma.

C, 65-year-old woman with recurrent dull, aching

epigastric pain. Axial MDCT image shows 3.5-cm

microcystic lesion (arrow) in pancreatic body and tail

with multiple small loculations. Patient underwent

distal pancreatectomy because of considerable

symptoms. Histopathologic finding was serous

cystadenoma.

D, 67-year-old man with pancreatic ductal dilatation.

Curved multiplanar reformatted MDCT image shows

main pancreatic ductal dilatation (arrows) in region of

head and proximal body of pancreas with prominence

of pancreatic tail indicative of main duct intraductal

papillary mucinous neoplasm. Patient underwent

Whipple procedure. Histopathologic finding was main

duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with

ductal carcinoma in situ.

C D

344 AJR:200, February 2013

Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

Fig. 2—54-year-old man with incidentally detected

lesion in pancreatic tail.

A, Axial MDCT image shows 8-mm low-attenuation

lesion (arrow) in pancreatic tail. MRI was considered

for evaluation of internal morphologic features of

lesion and for assessing any communication with

main pancreatic duct.

B, Axial T2-weighted MR image shows T2

hyperintense lesion in tail of pancreas with mild

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

nodular wall thickening (arrow) along lateral wall.

C, Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows septate

cyst (arrow).

D, Axial T2-weighted gadolinium-enhanced MR

image shows enhancing nodular thickening (arrow)

of lateral wall. Distal pancreatectomy was performed

because of complex morphologic features of cyst,

especially enhancing solid component, and young

age. Histopathologic finding was side-branch

intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with low-

grade dysplasia.

A B

been reported for small cystic pancreatic le-

sions (≤ 3 cm). Sainani et al. [16] found that

MDCT had 71–84.2% accuracy for differen-

tiating mucinous and nonmucinous subtypes

of small cystic pancreatic lesions.

The presence of solid nodules, thick sep-

tations, and cyst wall thickening on MDCT

images favors the diagnosis of an aggressive

cystic lesion [2, 15, 16, 22, 30, 31]. Sahani

and colleagues [15] reported that pancreatic

protocol MDCT had sensitivities of 93.6%,

71.4%, and 86.4% for detecting morpholog-

ic features such as septa, mural nodules, and

main pancreatic duct communication. Kim C D

et al. [34] found that shape and wall thick-

ness (> 1 mm) were two independent pre- ing with MDCT. Sainani et al. [16] reported ic features of the cyst and reliably displays

dictors of malignancy of a macrocystic pan- that MRI had higher sensitivity than MDCT in small cystic lesions not obvious on MDCT

creatic lesion. Tomimaru et al. [35] reported showing ductal communication of small cys- images [16]. Sainani et al. [16] reported that

that the presence or absence of mural nod- tic pancreatic lesions (100% vs 85.7%). In ad- MRI had an accuracy of 78.9–81.6% for dif-

ules on CT images had a sensitivity, specific- dition, inflammatory changes from concurrent ferentiating mucinous and nonmucinous sub-

ity, and accuracy of 93%, 80%, and 86% in pancreatitis can obscure the morphologic de- types of small pancreatic cystic lesions (≤ 3

the diagnosis of malignant IPMNs. Sainani tails of cystic pancreatic lesions. cm). They also reported that MRI had a sen-

and colleagues [16] found that in the detec- sitivities of 91% and 100% in the assessment

tion of small cystic pancreatic lesions (≤ 3 MRI and MRCP of septa and main pancreatic duct communi-

cm), MDCT had 73.9% sensitivity for the as- MRI of the pancreas with MRCP has cation in small cystic pancreatic lesions.

sessment of septa and 86% sensitivity for de- emerged as a reliable tool for detecting and The transition from 2D software to higher-

piction of ductal communication. characterizing cystic pancreatic lesions. The quality 3D acquisition has resulted in more ef-

MDCT has the additional advantage of de- superior soft-tissue and contrast resolution fective detection of connections with the main

picting calcifications, which can be difficult makes MRI a sensitive study for assessing pancreatic duct compared with the 2D single-

to recognize on MR images. Despite its im- the morphologic features of cystic lesions, slab technique [37, 38]. Yoon et al. [38] found

proved performance in the assessment of the including their communication with the main that compared with 2D MRCP, 3D MRCP fa-

biologic characteristics of pancreatic cysts, pancreatic duct [3, 16, 30, 36, 37]. Visser and cilitated superior evaluation of the pancreatic

false-negative results can occur because the colleagues [30] found that MRI had an accu- duct and the morphologic details of IPMNs.

dysplastic changes in the cystic lesions do not racy of 85–91% in establishing the diagno- The 2D MRCP sequence is usually performed

have distinct MDCT features [15]. In addi- sis of malignancy in cystic pancreatic lesions. as a breath-hold coronal single-shot fast spin-

tion, MDCT has limited utility for differenti- Lee et al. [2] found that MRI had an accuracy echo sequence or HASTE sequence [37, 38].

ating minimally invasive carcinoma from car- of 73.2–79.2% in determining the malignan- The 3D imaging technique is a high-spatial-

cinoma in situ. Similarly, the recognition of cy of cystic pancreatic lesions. In particular, resolution MRCP sequence that entails either

internal details and pancreatic duct communi- in small cystic lesions (≤ 3 cm), MRI facili- a breath-hold turbo spin-echo sequence or a

cation in a small cystic lesion can be challeng- tates confident assessment of the morpholog- respiratory-triggered fast spin-echo approach

AJR:200, February 2013 345

Sahani et al.

[37, 38]. An additional advantage of MRI with Although MRCP is more sensitive in dis- ing (multiplanar reconstructions and curved

or without MRCP is in the follow-up of young playing the details of cystic lesions, in most reformations) can provide sufficient detail

patients with cystic pancreatic lesions because cases appropriately performed thin-section on cystic lesions to allow decision making

MRI eliminates exposure to ionizing radiation. MDCT in combination with image process- [15, 16]. Variants in anatomy of the pancre-

atic ductal system can be confidently defined

with both MDCT and MRCP. This capability

is important in cases of ductal anatomic vari-

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

ants such as pancreas divisum. The presence

of such an anomaly can influence the surgical

approach. A main duct IPMN affecting the

dorsal duct can be treated with newer surgical

techniques involving dorsal pancreatectomy

and sparing the ventral pancreas, thus avoid-

ing biliary and pancreatic anastomoses [39].

Secretin-enhanced MRCP is a modified

MRCP technique in which MRI is performed

after stimulation of pancreatic exocrine func-

tion by IV injection of secretin [36, 37, 40].

Through stimulation of pancreatic secretion,

secretin administration can improve the utility

A B

Fig. 3—69-year-old woman with incidentally

detected cyst in pancreatic head.

A, Axial T2-weighted MR image shows 17-mm

hyperintense lesion (arrow) in pancreatic head.

B, Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted fat-saturated

MR image shows suspicious nodular enhancement

(arrow) along cyst wall. Close imaging follow-up was

performed.

C and D, Follow-up MR images 1 year after B show

nodule (arrow) within lesion on T2-weighted image

(C) that was enhancing on gadolinium-enhanced

T1-weighted fat-saturated image (D). Middle

pancreatectomy was performed because of enlarging

enhancing component in cyst. Histopathologic finding

was side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous

neoplasm with low- to moderate-grade dysplasia.

Operative decision was based on development of

suspicious features on follow-up images. Case falls

into category of cyst with solid component.

C D

A B C

Fig. 4—61-year-old woman undergoing follow-up of side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in pancreas.

A, Axial T2-weighted MR image shows 12-mm T2 hyperintense lesion (arrow) in pancreatic neck that had communication with pancreatic duct on MRCP images (not

shown). No enhancing solid components or main ductal dilatation was seen. Yearly surveillance with MRI was prescribed.

B, Axial T2-weighted MR image 1 year after A shows stability of lesion size (arrow) and no development of suspicious features.

C, Axial T2-weighted MR image 2 years after A shows stability of side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (arrow). T2 hyperintense simple cyst in left kidney

is incidental finding.

346 AJR:200, February 2013

Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

of MRCP in evaluating ductal anatomy and

the communication of small cystic pancreat-

Cystic Pancreatic

No specific imaging

Neuroendocrine

ic lesions [36, 37, 40]. However, the clinical

Neoplasm

Head, body, tail

Present (thick)

benefit of secretin MRCP in the care of pa-

tients with IPMN and other cystic lesions is

features

Present

5th–6th

Absent

Absent

Absent

currently unknown.

F=M

Oval

NA

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

PET and PET/CT

As in a number of other malignancies, PET

Solid Pseudopapillary

invasion or enlarged

nodes (all have very

has a potential advantage in detection of meta-

Neoplasmc

static spread of invasive pancreatic neoplasms

Large size, local

low malignant

[41]. Hybrid PET/CT with 18F-FDG allows

Uncommon

potential)

Unilocular

Body, tail

assessment of tumor extent and microinva-

2nd–4th

Present

Absent

Absent

Absent

sion in minimally invasive disease, which can

Oval

be missed with other imaging techniques [42,

Fb

43]. The sensitivity of PET/CT for detecting

Mucinous Neoplasm

Intraductal Papillary

Main pancreatic duct

carcinoma in situ and borderline lesions re-

Diffuse pancreatic

> 10 mm; nodules

TABLE 1: General Features and Imaging Appearances of Commonly Encountered Pancreatic Cystic Lesions

mains unsatisfactory [44, 45]. A few studies

M > F (60%/40%)

Main Duct

duct dilatation

Head, body, tail

have shown that PET/CT performs marginally

Uncommon

better than MDCT alone in the detection and

present

Present

6th–7th

Absent

Absent

characterization of malignant cystic pancre-

NA

NA

atic neoplasms [35, 46]. In a study of 72 pa-

tients, Tomimaru et al. [35] found that with a

cutoff maximum standardized uptake value of

Mucinous Neoplasm

Intraductal Papillary

mucinous neoplasms

septa; mural nodules

Size > 3 cm; main duct

intraductal papillary

thick irregular wall,

dilatation (> 6 mm);

2.5, FDG PET had sensitivity, specificity, and

Usually present as a

Uncommon (septal)

Side Branch

and large lesions

accuracy of 93%, 100%, and 96% in the di-

M > F (60%/40%)

Present in mixed

Bunch of grapes

Head, body, tail

agnosis of malignant IPMN. Likewise, Sperti

Macrocystic

and colleagues [42] found that FDG PET was

channel

Present

6th–7th

Absent

useful in the differentiation of benign and ma-

lignant IPMNs with a specificity, sensitivity,

and accuracy of 92%, 97%, and 95%. Man-

Solid areas and irregular

sour et al. [45] found that PET had sensitivity

Macrocystic (< 6, each

Present (usually thick)

Mucinous Cystic

Present (peripheral)

and specificity of 57% and 85% in determina-

Neoplasm

wall; peripheral

tion of the malignancy of pancreatic cystic tu-

calcification

mors. The major limitations of PET/CT in the

evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions include

Body, tail

> 2 cm)

4th–5th

Absent

Absent

Absent

higher cost, false-negative results for border-

Oval

bMore than 90% of patients with solid pseudopapillary neoplasm are women [25].

line and in situ tumors, and false-positive up-

Fa

take in areas of lesion-associated pancreatitis

and postbiopsy changes [35, 46]. Therefore,

Present (20–30%)

cAll solid pseudopapillary neoplasms have very low malignant potential.

Cystadenoma

Present (central)

F > M (75%/25%)

Microcystic (> 6,

Note—Data from [14, 18–20, 24, 25, 27, 60, 69, 70]. NA = not applicable.

Typically benign

there are not enough data to justify a role of

aMucinous cystic neoplasms occur almost exclusively in women [19].

Head, body, tail

each < 2 cm)

Serous

Present (thin)

PET/CT in the characterization of cystic pan-

Lobulated

creatic lesions [47].

6th–7th

Absent

Absent

Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound is an excellent im-

Present (usually thin,

aging technique for detecting signs predictive

Involved in chronic

thick if infected)

Pseudocyst

Uncommon (rim)

of malignancy or aggressiveness in cystic

Head, body, tail

pancreatitis

multilocular

pancreatic lesions. Such signs include inter-

Uncommon

Unilocular/

nal septations, mural nodules, solid masses,

Variable

3rd–7th

Absent

vascular invasion, and lymphatic metastasis

None

M>F

[48, 49]. An additional benefit is its capability

for sampling fluid and solid components and

Main pancreatic duct

Main pancreatic duct

Imaging predictors of

depicting debris and wall thickness [50]. En-

Characteristic

communication

doscopic ultrasound also shows the details of

involvement

Calcifications

Age (decade)

malignancy

the pancreatic parenchyma and the pancreat-

Central scar

Loculation

ic duct. In a study involving 50 patients, Kim

Location

Shape

et al. [51] found that endoscopic ultrasound

Wall

Sex

had sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of

AJR:200, February 2013 347

Sahani et al.

TABLE 2: Management of Commonly Encountered Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas

Lesion Malignant Potential Recommendation

Pseudocyst None Referral to gastroenterologist or pancreatic

surgeon if lesion is symptomatic

Serous cystadenoma Very low (malignant lesion is termed serous Serial imaging annually for 3 y; referral to surgeon

cystadenocarcinoma) if lesions is symptomatic or larger than 4 cm; for

patients at poor surgical risk, endoscopic

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

ultrasound (fine-needle aspiration to confirm

diagnosis and rule out malignancy)

Mucinous cystic neoplasm 6–36% prevalence of invasive carcinoma [19] Resection if patient’s condition allows surgery

(malignant lesion is termed mucinous

cystadenocarcinoma)

Side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous 6–46% risk of development of high-grade dysplasia Resection—if lesion is symptomatic, larger than

neoplasm or malignancy [18] 30 mm, or mural nodules or main duct dilatation

larger than 6 mm is present; if lesion is not

resectable, imaging follow-upa is recommended;

yearly follow-up imaging if lesion is smaller than

10 mm, 6- to 12-mo follow-up imaging if 10–20

mm, 6-mo follow-up if > 20 mm

Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous 57–92% risk of development of high-grade Resection if patient’s condition allows surgery

neoplasm dysplasia or malignancy within 5 y; follow-up

typically not conducted because the prevalence

of carcinoma and carcinoma in situ at diagnosis

is high [18]

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm Low malignant potential [25] Resection if patient’s condition allows surgery

Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm Variable malignant potential [25] Resection if patient’s condition allows surgery

aFollow-up guidelines are based on Sendai criteria [22].

90.5%, 86.2%, and 88% for differentiating with endoscopic ultrasound for definitive di- terization, but the yield of cytologic evalua-

cystic from solid pancreatic lesions. Kim and agnosis (Table 3). In a multicenter trial that tion is often limited by low cellularity of the

colleagues also found that the sensitivity of included 341 patients with cystic pancreatic fluid aspirate [18–20].

endoscopic ultrasound for characterization of lesions [56], endoscopic ultrasound had low

septa (77.8%), mural nodules (58.3%), main sensitivity (56%) and specificity (45%) for Evidence-Based Management

pancreatic duct dilatation (85.7%), and main differentiation of mucinous and nonmuci- Guidelines

pancreatic duct communication (88.9%) was nous cystic lesions on the basis of endoscop- Imaging Appearance

comparable to that of MRI. However, endo- ic ultrasound morphologic features. Howev- Optimal management of cystic pancreat-

scopic ultrasound is invasive and operator er, based on results of cytologic (fine needle ic lesions begins with morphologic classifi-

dependent, and these limitations have led to aspiration [FNA]) evaluation, sensitivity, cation into one of four types: unilocular, mi-

considerable variability in determining accu- specificity, and accuracy were 34.5%, 83%, crocystic, macrocystic, and cysts with solid

racy in differentiating benign and malignant and 51%. Biochemical analysis of the cyst components [27]. Unilocular cysts are thin-

lesions [48, 52–54]. Ahmad et al. [55] found fluid aspirate for estimation of carcinoem- walled simple cystic lesions without internal

only fair agreement (κ = 0.24) between expe- bryonic antigen (CEA), mucin, and amylase septa, solid components, or calcifications [24,

rienced endosonographers in the diagnosis of concentrations can facilitate reliable differ- 27]. Pseudocysts are the most common lesion

neoplastic versus nonneoplastic cystic pan- entiation of mucinous and nonmucinous cys- in this category, and usually, features of pan-

creatic lesions. In addition, several investiga- tic neoplasms [18–20, 25, 56]. A cutoff CEA creatitis, such as inflammation, atrophy, and

tors have noted difficulty in sampling lesions concentration of 192 ng/mL has been found pancreatic parenchymal calcifications, are

smaller than 3 cm [48, 52–54]. Currently, en- to have 84% specificity in differentiation of also seen [24, 27]. In rare instances, IPMNs,

doscopic ultrasound with or without aspira- mucinous from nonmucinous lesions [54, SCAs (< 10%), MCNs, and lymphoepitheli-

tion is used in the following instances: in- 56–59]. Cyst fluid amylase concentration al cysts present as unilocular cysts [27, 60].

determinate MDCT or MRCP findings; care also is helpful in differentiating pseudocysts Microcystic lesions typically present with

of patients at high surgical risk owing to co- from lesions that are not pseudocysts [56, 58, multiple tiny cysts (more than six, each mea-

morbid conditions or advanced age, which 59]. Although amylase concentrations less suring < 2 cm) with lobulated outlines and

precludes them from undergoing extensive than 250 U/L are helpful for excluding pseu- thick or fleshy stroma [20, 27, 60, 61]. The

surgery; and confirmation of the malignant docysts, concentrations greater than 250 U/L microcystic appearance is typically seen in

status of a cystic lesion before it is resected are nonspecific because they occur not only SCAs, and the pathognomic fibrous central

[48, 52–54]. in pseudocysts but also in benign IPMNs and scar is present in only 30% of cases [20, 27,

Endoscopic ultrasound–guided cyst fluid MCNs [58]. FNA cytologic evaluation of the 60, 61]. Microcystic lesions can have avid

aspiration is often performed in conjunction cyst fluid is also performed for cyst charac- enhancement on arterial phase images after

348 AJR:200, February 2013

Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

TABLE 3: Fluid Characteristics of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions

Mucinous Cystic Intraductal Papillary Solid Pseudopapillary

Characteristic Pseudocyst Serous Cystadenoma Neoplasm Mucinous Neoplasm Neoplasm

Nature Turbid, hemorrhagic Thin and clear, possibly bloody Thick and viscous Thick and viscous Possibly bloody

Viscosity Low Low High High NA

Mucin content Low Low High High NA

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Carcinoembryonic antigen < 5 ng/mL < 5 ng/mL High (> 192 ng/mL) High (> 192 ng/mL) NA

concentration

Amylase concentration High (> 250 U/L) Low (< 250 U/L) Variablea Variablea Low

Glycogen content None Abundant None None None

Note—Data from [20, 24, 58]. NA = not applicable.

aHigh concentration of amylase (> 250 U/L) can be seen in benign intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and benign mucinous cystic neoplasms.

IV contrast injection owing to the presence component, which includes tumors such as they are usually surgically treated at diagno-

of a vascular epithelial lining. This effect is pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm, solid sis [22]. The imaging predictors of malig-

especially pronounced in lesions with a very pseudopapillary neoplasm, adenocarcinoma nancy in MCNs include large size (> 4 cm)

small cyst size, causing them to masquerade of the pancreas, and metastatic lesions [27]. and the presence of mural nodules and egg-

as solid pancreatic neoplasms such as neu- Both MDCT and MRI can depict the presence shell calcification [22]. Because the natural

roendocrine tumors and metastatic lesions of enhancing solid components in a cystic le- history of MCNs can follow a stepwise pro-

from a primary cancer such as renal cell car- sion, which is diagnostic for this category of gression to malignancy, these lesions typi-

cinoma or melanoma [60]. Delayed phase lesions. The lesions encountered in this cate- cally require a more aggressive approach,

contrast-enhanced images can show the mi- gory are either frankly malignant or have high even when obvious imaging evidence of ma-

crocysts and the enhancing stroma. Similar- malignant potential. Therefore, surgical re- lignant behavior is lacking at the initial pre-

ly, T2-weighted MR images can confirm the section is the preferred management [27, 63]. sentation [15, 22].

presence of high-signal-intensity microcysts The prevalence of biologic aggressiveness

[20, 60]. Most SCAs have a microcystic ap- Management Guidelines of cystic lesions varies from 44.6% to 60%

pearance on images. Oligocystic and macro- With MDCT and MRI, a selective man- [6, 15, 30]. Biologically aggressive cystic le-

cystic patterns of SCA have been described agement approach can be considered for each sions include those with overtly malignant

in fewer than 10% of patients, and they can patient after factors such as clinical presenta- features and lesions with higher likelihood of

be difficult to differentiate from mucinous tion, age, sex, and surgical risk are accounted becoming malignant (histopathologic finding

neoplasms on imaging [20, 61, 62]. for [12, 22, 63, 64] (Figs. 5 and 6). The even- of moderate- to high-grade dysplasia) [10, 68,

Macrocystic lesions are composed of few- tual management paradigm should weigh the 69]. The prevalence of potential malignancy is

er cysts than are microcystic lesions, and the risk of aggressiveness and the benefit of pan- higher in mucinous than in nonmucinous le-

cysts are often larger than 2 cm in diameter creatic resection. It should also include risk sions [15, 31, 67, 68]. Mucinous cystic lesions

[18, 19, 27]. MCNs and side-branch IPMNs of development of advanced dysplastic or in- with low-grade dysplastic changes (adeno-

are included in this category. Patient demo- vasive changes in presumed mucinous lesions mas) are generally considered benign, and the

graphics (age, sex) and presence or absence of [12, 22, 63]. Surgery is often recommended risk of malignant transformation is unknown.

cyst communication can be used to differen- for symptomatic cystic lesions, cystic lesions Therefore, aggressive monitoring after surgi-

tiate MCNs and side-branch IPMNs [18, 19, having complex morphologic features (e.g., cal resection is not necessary [70–73].

27]. MCNs are common among middle-aged solid components), and cystic lesions detect- On the basis of involvement of the pancre-

women, are usually well defined, and are often ed in patients younger than 50 years [12, 22, atic duct, IPMNs are classified as either main

located in the pancreatic tail [18, 19, 24, 27]. 63]. Asymptomatic SCAs larger than 4 cm of- duct IPMN, side-branch IPMN, or mixed vari-

Side-branch IPMNs are commonly detected in ten are resected because of a high likelihood of ant IPMN involving both the main pancreatic

older men and are more frequently located in rapid growth and a propensity to development duct and side branches [14, 18, 22, 27]. IPMNs

the proximal pancreas (head and uncinate pro- of symptoms [65, 66]. Because mucinous le- have distinct histologic subtypes: gastric, in-

cess) [18, 19, 24, 27]. An important differenti- sions have a higher propensity toward aggres- testinal, pancreatobiliary, and oncocytic [74].

ating feature between MCN and IPMN is visu- sive biologic behavior at detection and toward Main duct IPMNs often have intestinal-type

alization of pancreatic ductal communication. later transformation, knowledge of the muci- epithelium, and side-branch IPMNs usually

If a clear channel of communication with the nous nature of cystic lesions influences man- have gastric-type epithelium [74]. Although all

pancreatic duct is visualized, the diagnosis of agement [22, 31, 67, 68]. In selected patients, morphologic variants of IPMN can progress to

side-branch IPMN is almost certain because endoscopic ultrasound–guided cyst aspiration cancer, invasive adenocarcinoma originat-

SCAs and MCNs do not communicate with and FNA can be considered if the imaging ing in gastric-type IPMNs is associated with

the pancreatic ductal system [16, 26]. findings are indeterminate or the risk of sur- a significantly worse survival rate than that

Cysts with solid components include true gery outweighs the benefits. originating from other types of IPMNs [74].

cystic tumors (MCNs, IPMNs) and solid pan- Because MCNs are encountered in young However, the imaging features are not spe-

creatic neoplasms associated with a cystic patients and are premalignant or malignant, cific for differentiating the various histologic

AJR:200, February 2013 349

Sahani et al.

variants of IPMNs. IPMNs can be managed ei-

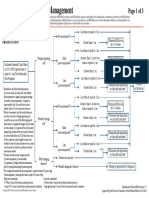

ther surgically or conservatively, depending on Pancreatic cystic mass detected with MDCT or MRI

their characteristics, the clinical presentation,

and the patient’s age. Because of the higher

Macrocystic or cyst with Cyst with solid components

risk of invasive cancer associated with main Unilocular Microcystic

septa (indeterminate) or with suspicious features

duct lesions, resection is recommended for

all main duct and mixed variant IPMNs [14,

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

22, 75]. In patients whose condition is consid-

ered acceptable for surgery, the type of sur- Symptomatic ≥ 4 cm < 4 cm

Possible Possible

Indeterminate

MCN IPMN

gical resection is influenced by lesion loca-

tion and the extent of tumor foci in the duct

epithelium. For side-branch IPMNs, a surgi- EUS with or

Consider surgical See Figure 6

cal approach is undertaken if the patient has resection depending

without aspiration

on comorbidities

symptoms (pain, nausea, diarrhea, weight loss, and risk

jaundice), if there is main duct involvement or

dilatation (> 6-mm), if the cyst is larger than Benign Indeterminate Suspicious features

3 cm, or complex features such as a thick ir-

< 3 cm

regular wall, thick septa, and solid nodules are ≥ 3 cm

identified on imaging [22].

Because side-branch IPMNs without com- Follow-up imaging

Consider surgical resection depending

on comorbidities and risk

plex morphologic features usually have low

malignant potential, surgical management is

not always warranted [4, 22]. Although the Fig. 5—Flowchart shows management guidelines for pancreatic cystic lesions seen on imaging. Suspicious

incidence of potential malignancy is low- features include presence of mural nodules, main duct dilatation, solid component, symptoms, and thick wall

er for smaller lesions (< 3 cm), the presence or septations. Differentiation of possible intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and mucinous cystic

neoplasm (MCN) is based on classic imaging features. EUS = endoscopic ultrasound.

of suspicious features on images, even in a

small cystic lesion, should be approached

more aggressively [8, 16]. Therefore, despite ence and the patient’s age. Although MDCT ture (Fig. 6). In patients in whom endoscop-

the low incidence of aggressiveness of mu- and MRI are both accepted methods for fol- ic ultrasound findings indicate a cystic lesion

cinous cystic lesions 3 cm and smaller, the low-up of these lesions, for adults younger is benign, follow-up is performed in accor-

incidence is not low enough to dismiss the than 50 years, MRI can be considered ow- dance with the size of the cystic lesion.

lesions entirely, and careful review of the im- ing to concerns about radiation exposure from

aging features is mandated. In addition, pa- MDCT. Regardless of the type of imaging Surgical Management

tients whose condition is found not suitable modality used, contrast-enhanced examina- A variety of open and laparoscopic surgi-

for surgical management often need frequent tions are crucial for improving detection of cal options are available for patients whose

assessments for growth and change in imag- enhancing solid components, the cyst wall, condition allows surgery. For lesions in the

ing features [14, 15, 22]. and septa. Contrast injection is desirable, but head of the pancreas, such as an IPMN with

A panel of experts have proposed the Sen- for patients with compromised renal function one or more of the aforementioned suspicious

dai criteria as guidelines for the management and those with lower cancer risk (small lesion, features, either a standard Whipple procedure

of side-branch IPMNs [22]. The follow-up advanced age), follow-up CT or MRI can be or pylorus-sparing pancreaticoduodenectomy

guideline varies in accordance with the size performed without contrast injection. Howev- can be performed [5, 39, 78]. Medial segmen-

of side-branch IPMN [22]. Lesions small- er, if suspicious features are observed during tal pancreatectomy is performed for a lesion

er than 1 cm are evaluated annually; those follow-up examinations, IV contrast medium in the neck or the body of the pancreas. For

measuring 1–2 cm are evaluated every 6–12 should be used [77]. lesions involving the tail of the pancreas, the

months; and those measuring 2–3 cm are im- A vexing issue in the follow-up of pancre- spleen is assessed for involvement because it

aged at intervals of 3–6 months [22]. How- atic cystic lesions is the total duration of fol- does not necessarily have to be removed with

ever, authors of more recent studies have rec- low-up. It would be reasonable to increase the distal pancreas [5, 39, 78].

ommended considering a longer surveillance the follow-up intervals to 2 years for lesions

interval of 2 years for cystic lesions small- 2 cm and larger that are stable for 2 years. For Postsurgical Follow-Up

er than 3 cm after baseline detection in the lesions smaller than 2 cm, imaging follow-up The postsurgical follow-up of patients who

absence of mural nodules [63, 76]. Accord- can stop after stability has been found for 2 have undergone resection of cystic pancreat-

ingly, it would be prudent to perform follow- years. However, due consideration needs to ic neoplasms depends on the histologic fea-

up evaluations every 2 years for side-branch be given to the patient’s age, symptoms, and tures. Benign MCNs do not recur and there-

IPMNs smaller than 2 cm and to perform an- capability of undergoing surgical resection. fore require no postoperative follow-up [22].

nual evaluations for IPMNs measuring 2–3 At follow-up imaging, lesions that are in- Because the risk of local recurrence and dis-

cm [63, 76]. determinate or have a growth spurt of more tant metastasis is higher for malignant MCNs,

The choice of imaging modality for moni- than 1 cm/year, endoscopic ultrasound can postsurgical follow-up evaluations are needed

toring IPMNs depends on institutional prefer- be performed to confirm the malignant na- every 6 months [22]. The postsurgical surviv-

350 AJR:200, February 2013

Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

al rate for invasive IPMN varies between 35% because patients with IPMN are at increased that many of these operations are preventive.

and 60%, mortality being associated with can- risk of development of synchronous or meta- Most of these lesions are IPMNs that contain

cer recurrence, most commonly local or ex- synchronous invasive ductal adenocarcinoma only low-, moderate-, or high-grade dyspla-

trapancreatic metastasis [79–81]. The risk of [14] (Fig. 3). sia (what we used to refer to as in situ carci-

recurrence ranges from 3% to 11% [75, 79]. noma), and we remove them either because

In cases of local recurrence, completion pan- The Gastroenterologist’s Perspective we cannot reliably exclude invasive cancer

createctomy may be necessary. It is important The detection of a potentially malignant or because we believe that progression will

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

to emphasize that invasive IPMN has a bet- lesion in the pancreas causes considerable inevitably occur and the lesion will become

ter survival rate than pancreatic ductal adeno- anxiety to both patient and physician. The invasive, akin to the process that occurs in a

carcinoma [74]. Follow-up of a side-branch prevalence of incidentally identified cystic colonic polyp. The decision to operate, how-

IPMN should be pursued carefully, and the lesions of the pancreas is high, but it is in- ever, is not straightforward. Although pan-

time frame of follow-up should be based on creasingly becoming apparent that only a creatic surgery has become safer and the risk

the patient’s risk and the lesion size. Guide- small minority of such lesions progress to of dying after a Whipple procedure or dis-

lines laid down by the International Associa- cancer. Imaging, especially MRI, MDCT, tal pancreatectomy is less than 2% at most

tion of Pancreatology call for yearly follow-up and endoscopic ultrasound, plays an impor- major medical centers, the frequency of

evaluations of benign IPMNs and for imaging tant role in risk stratification, avoiding un- complications is still high (> 40%), and the

follow-up in conjunction with measurement necessary surgery, and safe follow-up of le- consequences of endocrine and exocrine in-

of serum markers (CEA and CA19-9) after re- sions that are not resected. Most incidentally sufficiency with loss of pancreatic tissue are

section of invasive IPMN [7, 22]. The follow- identified cystic lesions can be safely fol- not trivial. These risks have to be carefully

up imaging protocol used in these scenarios lowed up. Current international guidelines weighed against the potential benefit. Strik-

should consider the aggressiveness of the re- help in this regard. They are highly sensitive ing the right balance can be difficult because

sected lesion and the surgical margins. Most to identification of high-risk lesions (in situ most of these lesions occur in elderly per-

recurrences take place within 3 years. There and invasive cancer) but need further refine- sons, and our knowledge of the natural his-

have been reports [69, 82], however, of recur- ment to improve their positive predictive val- tory of IPMNs is incomplete.

rence after 5 years. If the surgical margins are ue for high-grade pathologic findings.

negative, benign lesions can be evaluated at Practice Recommendations

intervals of 1 year. Patients with borderline le- The Pancreatic Surgeon’s Perspective Annual imaging surveillance is gener-

sions or carcinoma in situ, a positive margin, Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are one ally sufficient for benign serous cystadeno-

or indeterminate cystic lesions in the pancreat- of the most common indications for pancre- mas smaller than 4 cm and for asymptomatic

ic remnant need more frequent evaluations for atic surgery. Because most of the cystic le- lesions. Asymptomatic thin-walled unilocular

the first 2–3 years [83]. An added objective of sions that we remove do not contain invasive cystic lesions smaller than 3 cm or side-branch

follow-up imaging is to detect invasive cancer, cancer and are asymptomatic, we can state IPMNs should be followed up with CT or MRI

at 6 and 12 months interval after detection and

then annually for 3 years. Cystic lesions with

IPMN detected with MDCT or MRI

more complex features or with growth rates

greater than 1 cm/year should be followed more

Main duct IPMN

closely or recommended for resection if the pa-

Asymptomatic side-branch

Combined IPMN

IPMN tient’s condition allows surgery. Symptomatic

Symptomatic side-branch IPMN

> 3 cm

cystic lesions, neoplasms with high malignant

2−3 cm

< 2 cm

potential, and lesions larger than 3 cm should

be referred for surgical evaluation. Endoscopic

High risk

Risk and benefits of surgery EUS ultrasound with FNA biopsy can be used preop-

Positive cytologic result Negative cytologic result

eratively to assess the risk of malignancy.

Low risk

Follow-up with imaging

Recommendations for Further

Research

Despite great strides in noninvasive imag-

Resection ing and endoscopic ultrasound in the charac-

Size < 1 cm Size 1−2 cm Size 2−3 cm

follow-up

yearly

follow-up

every

follow-up

every

terization of pancreatic cystic lesions, current

6−12 months 3−6 months imaging techniques are not accurate in the dif-

ferentiation of cystic lesions associated with

carcinoma in situ or high-grade dysplasia

Growth > 1 cm/y, increase in size to > 3 cm, suspicious features

from benign lesions. Though MDCT and MRI

can reliably depict cystic lesions with obvious

Fig. 6—Flowchart shows management guidelines for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). High- aggressive biologic features, their value for

risk factors for surgery are old age and presence of comorbid conditions. Low-risk factors for surgery are prediction of the biologic behavior of all the

young age and no comorbid conditions. Suspicious features are mural nodules, main duct dilatation, solid

component, symptoms, and thick wall or septations. Follow-up guidelines are based on Sendai criteria [22]. cysts is limited. Advanced techniques such as

EUS = endoscopic ultrasound. PET/MRI with targeted radioisotopes have

AJR:200, February 2013 351

Sahani et al.

potential for characterization of changes at 10. Kirkpatrick ID, Desser TS, Nino-Murcia M, Jef- 23. Yamaguchi K, Kanemitsu S, Hatori T, et al. Pan-

the molecular level. Endoscopic ultrasound– frey RB. Small cystic lesions of the pancreas: creatic ductal adenocarcinoma derived from

guided FNA and fluid analysis already have a clinical significance and findings at follow-up. IPMN and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma con-

specific role in surgical decision making [84]. Abdom Imaging 2007; 32:119–125 comitant with IPMN. Pancreas 2011; 40:571–580

However, though the commonly used cyst 11. Lahav M, Maor Y, Avidan B, Novis B, Bar-Meir S. 24. Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-

fluid CEA levels are useful in differentiating Nonsurgical management of asymptomatic inci- del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of

mucinous from nonmucinous cystic lesions dental pancreatic cysts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol the pancreas. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1218–1226

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

of the pancreas, they have no value for as- 2007; 5:813–817 25. Sakorafas GH, Smyrniotis V, Reid-Lombardo

sessing the degree of dysplasia in mucinous 12. Spinelli KS, Fromwiller TE, Daniel RA, et al. Cys- KM, Sarr MG. Primary pancreatic cystic neo-

lesions [59, 84]. Pancreatic cyst fluid DNA tic pancreatic neoplasms: observe or operate. Ann plasms of the pancreas revisited. Part IV. Rare

analysis that includes identification of KRAS2 Surg 2004; 239:651–657; discussion, 657–659 cystic neoplasms. Surg Oncol 2012; 21:153–163

gene mutations is being explored for predict- 13. Ohtsuka T, Kono H, Nagayoshi Y, et al. An in- 26. Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Blake M, Fernandez-Del

ing the aggressiveness of pancreatic cysts crease in the number of predictive factors aug- Castillo C, Lauwers GY, Hahn PF. Intraductal papil-

[84]. Few initial studies have shown promise ments the likelihood of malignancy in branch duct lary mucinous neoplasm of pancreas: multi-detector

with this technique over FNA and other types intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the row CT with 2D curved reformations—correlation

of cyst fluid analysis in predicting the biolog- pancreas. Surgery 2012; 151:76–83 with MRCP. Radiology 2006; 238:560–569

ic features of cysts [84]. Further studies are 14. Sahani DV, Lin DJ, Venkatesan AM, et al. Multi- 27. Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Saokar A, Fernandez-del

necessary to validate reliable molecular and disciplinary approach to diagnosis and manage- Castillo C, Brugge WR, Hahn PF. Cystic pancreatic

imaging markers for accurate prediction of ment of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms lesions: a simple imaging-based classification sys-

the biologic behavior of cysts and to guide of the pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; tem for guiding management. RadioGraphics 2005;

the management of pancreatic cystic lesions. 7:259–269 25:1471–1484

15. Sahani DV, Sainani NI, Blake MA, Crippa S, 28. Kawamoto S, Lawler LP, Horton KM, Eng J,

References Mino-Kenudson M, del-Castillo CF. Prospective Hruban RH, Fishman EK. MDCT of intraductal

1. Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, et al. Preva- evaluation of reader performance on MDCT in papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas:

lence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. characterization of cystic pancreatic lesions and evaluation of features predictive of invasive carci-

AJR 2008; 191:802–807 prediction of cyst biologic aggressiveness. AJR noma. AJR 2006; 186:687–695

2. Lee HJ, Kim MJ, Choi JY, Hong HS, Kim KA. 2011; 197:72; [web]W53–W61 29. Taouli B, Vilgrain V, Vullierme MP, et al. Intra-

Relative accuracy of CT and MRI in the differen- 16. Sainani NI, Saokar A, Deshpande V, Fernandez- ductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas:

tiation of benign from malignant pancreatic cystic del Castillo C, Hahn P, Sahani DV. Comparative helical CT with histopathologic correlation. Radi-

lesions. Clin Radiol 2011; 66:315–321 performance of MDCT and MRI with MR cho- ology 2000; 217:757–764

3. Zhang XM, Mitchell DG, Dohke M, Holland GA, langiopancreatography in characterizing small 30. Visser BC, Yeh BM, Qayyum A, Way LW, Mc-

Parker L. Pancreatic cysts: depiction on single- pancreatic cysts. AJR 2009; 193:722–731 Culloch CE, Coakley FV. Characterization of

shot fast spin-echo MR images. Radiology 2002; 17. Curry CA, Eng J, Horton KM, et al. CT of pri- cystic pancreatic masses: relative accuracy of CT

223:547–553 mary cystic pancreatic neoplasms: can CT be and MRI. AJR 2007; 189:648–656

4. Correa-Gallego C, Ferrone CR, Thayer SP, Wargo used for patient triage and treatment? AJR 2000; 31. Procacci C, Carbognin G, Accordini S, et al. CT

JA, Warshaw AL, Fernandez-Del Castillo C. Inci- 175:99–103 features of malignant mucinous cystic tumors of

dental pancreatic cysts: do we really know what we 18. Sakorafas GH, Smyrniotis V, Reid-Lombardo KM, the pancreas. Eur Radiol 2001; 11:1626–1630

are watching? Pancreatology 2010; 10:144–150 Sarr MG. Primary pancreatic cystic neoplasms re- 32. Chaudhari VV, Raman SS, Vuong NL, et al. Pan-

5. Ferrone CR, Correa-Gallego C, Warshaw AL, et visited. Part III. Intraductal papillary mucinous neo- creatic cystic lesions: discrimination accuracy

al. Current trends in pancreatic cystic neoplasms. plasms. Surg Oncol 2011; 20:e109–e118 based on clinical data and high resolution CT fea-

Arch Surg 2009; 144:448–454 19. Sakorafas GH, Smyrniotis V, Reid-Lombardo tures. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2007; 31:860–867

6. Goh BK, Tan YM, Thng CH, et al. How useful are KM, Sarr MG. Primary pancreatic cystic neo- 33. Chaudhari VV, Raman SS, Vuong NL, et al. Pan-

clinical, biochemical, and cross-sectional imaging plasms revisited. Part II. Mucinous cystic neo- creatic cystic lesions: discrimination accuracy

features in predicting potentially malignant or ma- plasms. Surg Oncol 2011; 20:e93–e101 based on clinical data and high-resolution com-

lignant cystic lesions of the pancreas? Results from 20. Sakorafas GH, Smyrniotis V, Reid-Lombardo puted tomographic features. J Comput Assist To-

a single institution experience with 220 surgically KM, Sarr MG. Primary pancreatic cystic neo- mogr 2008; 32:757–763

treated patients. J Am Coll Surg 2008; 206:17–27 plasms revisited. Part I. Serous cystic neoplasms. 34. Kim SH, Lim JH, Lee WJ, Lim HK. Macrocystic

7. Lévy P, Jouannaud V, O’Toole D, et al. Natural Surg Oncol 2011; 20:e84–e92 pancreatic lesions: differentiation of benign from

history of intraductal papillary mucinous tumors 21. Sadakari Y, Ienaga J, Kobayashi K, et al. Cyst size premalignant and malignant cysts by CT. Eur J

of the pancreas: actuarial risk of malignancy. Clin indicates malignant transformation in branch duct Radiol 2009; 71:122–128

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:460–468 intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the 35. Tomimaru Y, Takeda Y, Tatsumi M, et al. Utility of

8. Handrich SJ, Hough DM, Fletcher JG, Sarr MG. pancreas without mural nodules. Pancreas 2010; 2-[18F] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emis-

The natural history of the incidentally discovered 39:232–236 sion tomography in differential diagnosis of benign

small simple pancreatic cyst: long-term follow-up 22. Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, et al. International and malignant intraductal papillary-mucinous neo-

and clinical implications. AJR 2005; 184:20–23 consensus guidelines for management of intra- plasm of the pancreas. Oncol Rep 2010; 24:613–620

9. Kimura W, Nagai H, Kuroda A, Muto T, Esaki Y. ductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and muci- 36. Fukukura Y, Fujiyoshi F, Sasaki M, Nakajo M.

Analysis of small cystic lesions of the pancreas. nous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancre- Pancreatic duct: morphologic evaluation with MR

Int J Pancreatol 1995; 18:197–206 atology 2006; 6:17–32 cholangiopancreatography after secretin stimula-

352 AJR:200, February 2013

Cystic Pancreatic Lesions

tion. Radiology 2002; 222:674–680 pancreatic cysts: clinicopathologic characteristics enoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. World J

37. Sandrasegaran K, Lin C, Akisik FM, Tann M. State- and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Gastroenterol 2009; 15:2739–2747

of-the-art pancreatic MRI. AJR 2010; 195:42–53 Surg 2003; 138:427–423; discussion, 423–424 62. Kim SY, Lee JM, Kim SH, et al. Macrocystic neo-

38. Yoon LS, Catalano OA, Fritz S, Ferrone CR, Hahn 49. Kubo H, Chijiiwa Y, Akahoshi K, et al. Intraduct- plasms of the pancreas: CT differentiation of se-

PF, Sahani DV. Another dimension in magnetic al papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas: rous oligocystic adenoma from mucinous cystad-

resonance cholangiopancreatography: comparison differential diagnosis between benign and malig- enoma and intraductal papillary mucinous tumor.

of 2- and 3-dimensional magnetic resonance cho- nant tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J AJR 2006; 187:1192–1198

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

langiopancreatography for the evaluation of intra- Gastroenterol 2001; 96:1429–1434 63. Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM, et al. Man-

ductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pan- 50. Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Lewis JD, Ginsberg aging incidental findings on abdominal CT: white

creas. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2009; 33:363–368 GG. Can EUS alone differentiate between malig- paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J

39. Thayer SP, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Balcom JH, nant and benign cystic lesions of the pancreas? Am Coll Radiol 2010; 7:754–773

Warshaw AL. Complete dorsal pancreatectomy Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:3295–3300 64. Allen PJ, Jaques DP, D’Angelica M, Bowne WB,

with preservation of the ventral pancreas: a new 51. Kim YC, Choi JY, Chung YE, et al. Comparison Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Cystic lesions of the

surgical technique. Surgery 2002; 131:577–580 of MRI and endoscopic ultrasound in the charac- pancreas: selection criteria for operative and non-

40. Sanyal R, Stevens T, Novak E, Veniero JC. Secre- terization of pancreatic cystic lesions. AJR 2010; operative management in 209 patients. J Gastro-

tin-enhanced MRCP: review of technique and ap- 195:947–952 intest Surg 2003; 7:970–977

plication with proposal for quantification of exo- 52. Canto MI, Goggins M, Yeo CJ, et al. Screening 65. Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, Lauwers GY,

crine function. AJR 2012; 198:124–132 for pancreatic neoplasia in high-risk individuals: Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Serous

41. Kauhanen SP, Komar G, Seppanen MP, et al. A an EUS-based approach. Clin Gastroenterol Hep- cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates

prospective diagnostic accuracy study of 18F-fluo- atol 2004; 2:606–621 and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg

rodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/ 53. Emerson RE, Randolph ML, Cramer HM. Endo- 2005; 242:413–419; discussion, 419–421

computed tomography, multidetector row com- scopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration 66. Wargo JA, Fernandez-del-Castillo C, Warshaw

puted tomography, and magnetic resonance imag- cytology diagnosis of intraductal papillary muci- AL. Management of pancreatic serous cystadeno-

ing in primary diagnosis and staging of pancreatic nous neoplasm of the pancreas is highly predic- mas. Adv Surg 2009; 43:23–34

cancer. Ann Surg 2009; 250:957–963 tive of pancreatic neoplasia. Diagn Cytopathol 67. Horvath KD, Chabot JA. An aggressive resec-

42. Sperti C, Bissoli S, Pasquali C, et al. 18-Fluorode- 2006; 34:457–462 tional approach to cystic neoplasms of the pan-

oxyglucose positron emission tomography en- 54. Michaels PJ, Brachtel EF, Bounds BC, Brugge creas. Am J Surg 1999; 178:269–274

hances computed tomography diagnosis of malig- WR, Pitman MB. Intraductal papillary mucinous 68. Kawamoto S, Horton KM, Lawler LP, Hruban

nant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of neoplasm of the pancreas: cytologic features pre- RH, Fishman EK. Intraductal papillary mucinous

the pancreas. Ann Surg 2007; 246:932–937; dis- dict histologic grade. Cancer 2006; 108:163–173 neoplasm of the pancreas: can benign lesions be

cussion, 937–939 55. Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Brensinger C, et al. differentiated from malignant lesions with multi-

43. Sperti C, Pasquali C, Decet G, Chierichetti F, Interobserver agreement among endosonogra- detector CT? RadioGraphics 2005; 25:1451–

Liessi G, Pedrazzoli S. F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose phers for the diagnosis of neoplastic versus non- 1468; discussion, 1468–1470

positron emission tomography in differentiating neoplastic pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastrointest 69. Salvia R, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Bassi C, et al.

malignant from benign pancreatic cysts: a pro- Endosc 2003; 58:59–64 Main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neo-

spective study. J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9:22– 56. Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrows- plasms of the pancreas: clinical predictors of ma-

28; discussion, 28–29 ki E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neo- lignancy and long-term survival following resec-

44. Higashi T, Saga T, Nakamoto Y, et al. Diagnosis plasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst tion. Ann Surg 2004; 239:678–685; discussion,

of pancreatic cancer using fluorine-18 fluorode- study. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:1330–1336 685–687

oxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG 57. Hutchins GF, Draganov PV. Cystic neoplasms of 70. Hruban RH, Pitman MB, Klimstra DS. Tumors of

PET): usefulness and limitations in “clinical real- the pancreas: a diagnostic challenge. World J the pancreas. Washington, DC: American Regis-

ity.” Ann Nucl Med 2003; 17:261–279 Gastroenterol 2009; 15:48–54 try of Pathology and Armed Forces Institute of

45. Mansour JC, Schwartz L, Pandit-Taskar N, et al. 58. Park WG, Mascarenhas R, Palaez-Luna M, et al. Pathology, 2007:413

The utility of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose whole Diagnostic performance of cyst fluid carcinoem- 71. Crippa S, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Salvia R, et

body PET imaging for determining malignancy in bryonic antigen and amylase in histologically con- al. Mucin-producing neoplasms of the pancreas:

cystic lesions of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg firmed pancreatic cysts. Pancreas 2011; 40:42–45 an analysis of distinguishing clinical and epide-

2006; 10:1354–1360 59. Pitman MB, Michaels PJ, Deshpande V, Brugge miologic characteristics. Clin Gastroenterol Hep-

46. Hong HS, Yun M, Cho A, et al. The utility of F-18 WR, Bounds BC. Cytological and cyst fluid analysis atol 2010; 8:213–219

FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of pancreatic in- of small (< or =3 cm) branch duct intraductal papil- 72. Crippa S, Salvia R, Warshaw AL, et al. Mucinous

traductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Clin Nucl lary mucinous neoplasms adds value to patient man- cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggres-

Med 2010; 35:776–779 agement decisions. Pancreatology 2008; 8:277–284 sive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients.

47. Hara T, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, et al. Diagnosis 60. Choi JY, Kim MJ, Lee JY, et al. Typical and atyp- Ann Surg 2008; 247:571–579

and patient management of intraductal papillary- ical manifestations of serous cystadenoma of the 73. Fritz S, Warshaw AL, Thayer SP. Management of

mucinous tumor of the pancreas by using peroral pancreas: imaging findings with pathologic cor- mucin-producing cystic neoplasms of the pancre-

pancreatoscopy and intraductal ultrasonography. relation. AJR 2009; 193:136–142 as. Oncologist 2009; 14:125–136

Gastroenterology 2002; 122:34–43 61. Shah AA, Sainani NI, Kambadakone AR, et al. 74. Mino-Kenudson M, Fernandez-del Castillo C,

48. Fernandez-del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Predictive value of multi-detector computed to- Baba Y, et al. Prognosis of invasive intraductal

Rattner DW, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. Incidental mography for accurate diagnosis of serous cystad- papillary mucinous neoplasm depends on histo-

AJR:200, February 2013 353

Sahani et al.

logical and precursor epithelial subtypes. Gut 78. Yamaguchi K, Konomi H, Kobayashi K, et al. To- 81. Yokoyama Y, Nagino M, Oda K, et al. Clinico-

2011; 60:1712–1720 tal pancreatectomy for intraductal papillary-mu- pathologic features of re-resected cases of intra-

75. Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Intraductal cinous tumor of the pancreas: reappraisal of total ductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs).

papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an pancreatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2005; Surgery 2007; 142:136–142

updated experience. Ann Surg 2004; 239:788– 52:1585–1590 82. White R, D’Angelica M, Katabi N, et al. Fate of the

797; discussion, 797–799 79. Chari ST, Yadav D, Smyrk TC, et al. Study of re- remnant pancreas after resection of noninvasive in-

76. Das A, Wells CD, Nguyen CC. Incidental cystic currence after surgical resection of intraductal traductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. J Am Coll

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 80.82.77.83 on 10/08/17 from IP address 80.82.77.83. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

neoplasms of pancreas: what is the optimal inter- papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Surg 2007; 204:987–993; discussion, 993–995

val of imaging surveillance? Am J Gastroenterol Gastroenterology 2002; 123:1500–1507 83. Yamaguchi K, Ohuchida J, Ohtsuka T, Nakano K,

2008; 103:1657–1662 80. D’Angelica M, Brennan MF, Suriawinata AA, Tanaka M. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumor of

77. Macari M, Lee T, Kim S, et al. Is gadolinium nec- Klimstra D, Conlon KC. Intraductal papillary mu- the pancreas concomitant with ductal carcinoma of

essary for MRI follow-up evaluation of cystic le- cinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2002; 2:484–490

sions in the pancreas? Preliminary results. AJR clinicopathologic features and outcome. Ann Surg 84. Shi C, Hruban RH. Intraductal papillary muci-

2009; 192:159–164 2004; 239:400–408 nous neoplasm. Hum Pathol 2012; 43:1–16

F O R YO U R I N F O R M AT I O N

The AJR has made getting the articles you really want really easy with an online tool, Really Simple

Syndication, available at www.ajronline.org. It’s simple. Click the RSS button located in the

menu on the right side of the page. You’ll be on your way to syndicating your AJR content in no time.

354 AJR:200, February 2013

You might also like

- THE Ketofeed Diet Book v2Document43 pagesTHE Ketofeed Diet Book v2jacosta12100% (1)

- Breast Procedures Ultrasound Only EditedDocument107 pagesBreast Procedures Ultrasound Only EditedDanaNo ratings yet

- Grange Fencing Garden Products Brochure PDFDocument44 pagesGrange Fencing Garden Products Brochure PDFDan Joleys100% (1)

- Pitfalls in Diagnosis of HsilDocument1 pagePitfalls in Diagnosis of HsilMaryam ZainalNo ratings yet

- Drill Bit Classifier 2004 PDFDocument15 pagesDrill Bit Classifier 2004 PDFgustavoemir0% (2)

- AC7140 Rev CDocument73 pagesAC7140 Rev CRanga100% (1)

- Writing Short StoriesDocument10 pagesWriting Short StoriesRodiatun YooNo ratings yet

- Loan Agreement: Acceleration ClauseDocument2 pagesLoan Agreement: Acceleration ClauseSomething SuspiciousNo ratings yet

- Acr Incidental Findings Guidelines (598 - 0)Document20 pagesAcr Incidental Findings Guidelines (598 - 0)Yeang ChngNo ratings yet

- Definition Nature and Scope of Urban GeographyDocument4 pagesDefinition Nature and Scope of Urban Geographysamim akhtarNo ratings yet

- Wind LoadingDocument18 pagesWind LoadingStephen Ogalo100% (1)

- SS EN 1991-1-1-2008 (2017) - PreviewDocument16 pagesSS EN 1991-1-1-2008 (2017) - PreviewNg SHun JieNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic Cysts: Vaishali PatelDocument2 pagesPancreatic Cysts: Vaishali PatelEngin AltınkayaNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue Tumors Diagnosis, Evaluation, And.3Document10 pagesSoft Tissue Tumors Diagnosis, Evaluation, And.3Muhammad Iqbal AlpanzhoriNo ratings yet

- Solid Renal Masses: What The Numbers Tell Us: Stella K. Kang William C. Huang Pari V. Pandharipande Hersh ChandaranaDocument11 pagesSolid Renal Masses: What The Numbers Tell Us: Stella K. Kang William C. Huang Pari V. Pandharipande Hersh ChandaranaTạ Minh ZSNo ratings yet

- Sainani 2009Document10 pagesSainani 2009Patricia BezneaNo ratings yet

- Da1 MPDDocument14 pagesDa1 MPDBOMBLE SANSKRUTI JAYWANT 20BID0004No ratings yet

- Clin Management Ovarian Cysts WEB Algorithm-1Document3 pagesClin Management Ovarian Cysts WEB Algorithm-1linglingNo ratings yet

- Incidentaloma RsnaDocument16 pagesIncidentaloma Rsnarulitoss_41739No ratings yet

- Quantitative Elastography Methods in Liver Disease Current Evidence and Future DirectionsDocument26 pagesQuantitative Elastography Methods in Liver Disease Current Evidence and Future DirectionsValentina IorgaNo ratings yet

- Jhaveri Et Al 2013 Cystic Renal Cell Carcinomas Do They Grow Metastasize or RecurDocument5 pagesJhaveri Et Al 2013 Cystic Renal Cell Carcinomas Do They Grow Metastasize or Recurdigital tavernNo ratings yet

- TTB TtnaDocument17 pagesTTB TtnanurcholisNo ratings yet

- Malignant and Benign Breast Cancer Classification Using Machine Learning AlgorithmsDocument5 pagesMalignant and Benign Breast Cancer Classification Using Machine Learning AlgorithmsRohit SinghNo ratings yet

- LIVER CALCIFIED MASSES Types AlgorithmDocument11 pagesLIVER CALCIFIED MASSES Types Algorithmcalustre2016No ratings yet

- Discoid Lateral MeniscusDocument8 pagesDiscoid Lateral MeniscusGamaHariandaNo ratings yet

- Kutkut 2011 Sinus WidthDocument5 pagesKutkut 2011 Sinus WidthLamis MagdyNo ratings yet

- Knowing The Options: Benign / More Reassuring Features (Simple) Malignant / Suspicious FeaturesDocument3 pagesKnowing The Options: Benign / More Reassuring Features (Simple) Malignant / Suspicious FeaturesDen PajiboNo ratings yet

- J Natl Compr Canc Netw-2016-Von Mehren-758-86Document29 pagesJ Natl Compr Canc Netw-2016-Von Mehren-758-86Bogdan TudorNo ratings yet

- 2018 Mishra Local Recurrence Case StudyDocument4 pages2018 Mishra Local Recurrence Case Studynasifahsankhan4No ratings yet

- ACC GP MRI Service HandbookDocument22 pagesACC GP MRI Service HandbookBruno Souza BragaNo ratings yet

- A Case Report of Ancient Presacral SchwannomaDocument4 pagesA Case Report of Ancient Presacral SchwannomaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Doc-20240131-Wa0 240131 224157Document4 pagesDoc-20240131-Wa0 240131 22415722alhumidi2020No ratings yet

- Bile Duct StrictureDocument12 pagesBile Duct StricturechristianyecyecanNo ratings yet

- Clinics in Oncology: Pleomorphic Adenoma of Palate: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesClinics in Oncology: Pleomorphic Adenoma of Palate: A Case ReportIstigfarani InNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic and Functional Efficacy of Subcuticular Running Epidermal ClousureDocument7 pagesAesthetic and Functional Efficacy of Subcuticular Running Epidermal Clousureluisrmg91No ratings yet

- Analyst: Diagnosis of Early-Stage Esophageal Cancer by Raman Spectroscopy and Chemometric TechniquesDocument7 pagesAnalyst: Diagnosis of Early-Stage Esophageal Cancer by Raman Spectroscopy and Chemometric TechniquesJoelNo ratings yet

- Ajr 10 5540Document9 pagesAjr 10 5540Pepe pepe pepeNo ratings yet

- Published DCR Appy CPG 12 19Document14 pagesPublished DCR Appy CPG 12 19Ogbonnaya IfeanyichukwuNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer Screening - AHS GuidelineDocument9 pagesCervical Cancer Screening - AHS GuidelineBasil al-hashaikehNo ratings yet

- Radiologist, Be Aware: Ten Pitfalls That Confound The Interpretation of Multiparametric Prostate MRIDocument12 pagesRadiologist, Be Aware: Ten Pitfalls That Confound The Interpretation of Multiparametric Prostate MRITurkiNo ratings yet

- 30 Gibbs - Barrow Quarterly 25-1-2013Document7 pages30 Gibbs - Barrow Quarterly 25-1-2013xcskijoeNo ratings yet

- Imaging and Staging of Transitional Cell Carcinoma: Part 1, Lower Urinary TractDocument7 pagesImaging and Staging of Transitional Cell Carcinoma: Part 1, Lower Urinary TractdrelvNo ratings yet

- Imaging and Classification of Congenital Cystic Renal DiseasesDocument11 pagesImaging and Classification of Congenital Cystic Renal DiseasessuhartiniNo ratings yet

- Stoelinga 2021Document14 pagesStoelinga 2021ShagorNo ratings yet

- 8 Ortho Oncology - 210217 - 194331Document11 pages8 Ortho Oncology - 210217 - 194331Nabil AhmedNo ratings yet

- 1.41 (Surgery) Surgical Diseases of The Small BowelsDocument6 pages1.41 (Surgery) Surgical Diseases of The Small BowelsLeo Mari Go LimNo ratings yet

- Accp GuidelinesDocument28 pagesAccp GuidelinesBarbara Daniela Gonzalez EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Guia de IncidentalomasDocument2 pagesGuia de IncidentalomasAlexandra FreireNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Imaging of Bowel Pathology - Technique and Keys To Diagnosis in The Acute Abdomen, 2011Document9 pagesUltrasound Imaging of Bowel Pathology - Technique and Keys To Diagnosis in The Acute Abdomen, 2011Сергей СадовниковNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Study of Ovarian Cysts: Shivaji Neelgund, Panchaksharayya HiremathDocument5 pagesA Retrospective Study of Ovarian Cysts: Shivaji Neelgund, Panchaksharayya HiremathLauren RenNo ratings yet

- The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.6Document15 pagesThe American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.6Emanuella CirinoNo ratings yet

- Cystic Neoplasms of The PancreasDocument9 pagesCystic Neoplasms of The PancreasSanjaya SenevirathneNo ratings yet

- Mesenteric Cyst in InfancyDocument27 pagesMesenteric Cyst in InfancySpica AdharaNo ratings yet

- ReportsDocument2 pagesReportssawtulhassanNo ratings yet

- Imaging Analyses of Bone Tumors JBJSDocument11 pagesImaging Analyses of Bone Tumors JBJSVera VeraNo ratings yet

- Optimal Bowel Resection Margin in Colon Cancer Surgery 2023Document13 pagesOptimal Bowel Resection Margin in Colon Cancer Surgery 2023CIRUGÍA ONCOLÓGICA ABDOMENNo ratings yet

- Differentiation Between Malignant and Benign Gastric Ulcers: CT Virtual Gastroscopy Versus Optical Gastroendoscopy1Document9 pagesDifferentiation Between Malignant and Benign Gastric Ulcers: CT Virtual Gastroscopy Versus Optical Gastroendoscopy1Dipak Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- CR 48JACPAdrenalmediastinalcystDocument4 pagesCR 48JACPAdrenalmediastinalcystKartik DuttaNo ratings yet

- 3D Convolutional Neural Network For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm SegmentationDocument26 pages3D Convolutional Neural Network For Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm SegmentationIzzHyukNo ratings yet

- Positioning Existing: GingivaDocument4 pagesPositioning Existing: GingivaAna Maria Montoya GomezNo ratings yet

- American Society CPG On Management of Rectal CADocument32 pagesAmerican Society CPG On Management of Rectal CACecille ZacateNo ratings yet

- Management of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: Review ArticleDocument9 pagesManagement of Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: Review ArticleRaúl Sebastián LozanoNo ratings yet