Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Buddhist Deities and Mantras in The Hindu Tantras (Tantrasarasamgraha and Isanasiva Gurudeva Paddhati) PDF

Uploaded by

anjanaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Buddhist Deities and Mantras in The Hindu Tantras (Tantrasarasamgraha and Isanasiva Gurudeva Paddhati) PDF

Uploaded by

anjanaCopyright:

Available Formats

BUDDHIST DEITIES AND "MANTRAS" IN THE HINDU TANTRAS

(TANTRASARASAMGRAHA AND ISANASIVA GURUDEVA PADDHATI)

Author(s): Sanchita Ghosh

Source: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress , 2013, Vol. 74 (2013), pp. 110-114

Published by: Indian History Congress

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44158805

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Indian History Congress is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress

This content downloaded from

27.59.233.121 on Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BUDDHIST DEITIES AND MANTRAS IN

THE HINDU TANTRAS

(TANTRASARASAMGRAHA AND

ISANASIVA GURUDEVA PADDHATI)

Sanchita Ghosh

At various stages in its development Buddhism incorporated

Brahmanical and Hindu deities, but in its tantric form Buddhism has

also influenced the Hindu pantheon. The tantric period is characterized

by mutual influences between the two religions.

A. Sanderson has provided evidence for the influence of the tantric

Saiva canon on the Buddhist Yoganuttantras or Yoginitantra

demonstrates that passage. Brahmaya-mala (Picumata) the Tantras

Sadbhava the Yoginisam cara of the Jayadra thaya-mala and

Siddhayoges, varimata were incorporated with little or no modification

into the Buddhist Tantras of Samvara, such as the Laghu Samvara

(Herukabidhana) and Abhidhanottra the Samputodbhava, the

Samvarodaya, Vajradaka and Dakarvarnas.1

The influence of Brahmanical iconography on Buddhist tantric

iconography highlights similarities between the form of Siva and

Boddhisatva Simhanada Nikantha and others. As the well known

Buddhist tantric texts such as Abhayakara Gupta's eleventh century

Nispannayogavali include Brahmanical deities such as Ganesa,

Kartikeya, the directional guardians and heavenly bodies in the

periphery of the deity marídalas they describe.2

The reverse, mainly the influence of Tantric Buddhism on the later

Hindu tantric pantheon has been studied by B. Bhattacharya.3 It is

difficult to state who were the first to write the Tantric texts and who

borrowed it from whom. But after the study of iconography along with

deity mantras on the basis of Sadhanmala we can say that the Buddhists

were the first to write the Tantric texts and the Hindu Tantras borrowed

them. The best example is of Chinnmasta and the eight manifestations

of Tara known as Tara, Ugna, Mahogra, Vajraakali, (The Tantric)

Saras wati, Kameswari and Bhadrakali were adopted by the Hindu

pantheon from Buddhist Tantric sources.4 The Phetkarimitantra's

description of the goddess as Ugratara along with her surrounding

deities and elements of Buddhist Tantric worship procedures and

mantras became the authoritative description of the goddess and was

incorporated into many Hindu tantric texts such as Krasanda's

Tantrasara which traces the adoption of Bhutadamara into the Hindu

This content downloaded from

27.59.233.121 on Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient India 111

Pantheon by examining the two ext

belonging to the Buddhists and the oth

It is usually not easy to determine

adapted from one pantheon to another

Bhutadamara and Ugratara lay in the cl

process of adoption of a deity from the B

Tantras was possible.5

This paper of mine deals only with

tantricism on Hindu Tantras as evident

deities' mantras and elements of typic

procedure, Often we have no informa

they were written, nor who their auth

There are various sources which have shown these influences but

the important among them is Tantra Sara Samgraha (TSS) which is a

compilation of mantras sastra by Narayana, a Keralite Brahman. This

work is the colophons of chapters of the texts and is divided into thirty

two chapters written in Sanskrit and is popularly known as the

Visanaraniya (2- 1 0). It deals mainly with mantras to counter the effects

of poison (vis). Tantrasara Samgraha has an anonymous commentary

( vkahya ) which cites the Mantrapada of Isanagurudeva Paddhati. This

Mantrapada (MP) forms pada and patalas of Isansasiva gurudeva-

amisra's Isanasiva gurudeva padhati which is also known as

Tantrapadhati. The I.S.P. ( Isanagurudeva Paddhati) is a Saiva manual

of temple worship in four padas and is assigned to the last part of the

eleventh or early twelfth century. Most of the chapters in the M.P.

correspond to chapters in the TSS.6 My paper only deals with the deity

Yamantaka. The Isanagurudeva Paddhati (ISP) cites the mantra of

Yamantaka.7

Moreover, it is only one of the two mantras of Yamantaka found

in the M.P. which are borrowed from the Buddhist sources. In the M.P.

and the TSS the second mantra is identified as a mantra of Yama not

Yamantaka. The Buddhist mantras appears in the section of the M.P.,

which promotes the rites of black magic ( Abhicara ) which are said to

be revealed for the sake of the protection of (Vedic) dharma from the

enemies of the dharma and the Veda, which include the Buddhists.

Both the TSS8 and the M.P.9 address these issues.

The mantras of Yama / Yamantaka are to be inscribed in a yantra

which is employed in black magic (Abhicara). According to ST this is

a Yantra of Pretraj' i.e. Yama, the god of death which specifies its use

in the rite of liquidation.10 But the anonymous commentary on the TSS

states that the Yantra is perhaps to be used in the rite of causing

dissension since the TSS does not give precise information, whereas

This content downloaded from

27.59.233.121 on Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 12 IHC : Proceedings, 74th Session , 2013

the Buddhist sources say that these two mantras do occur in the squares

of a y antra.11

The mantra known in Buddhist tantrism as the mantra of Yamantaka

especially of the form Vahrabhairva and continues to be recited up to

the present.12 Vajrabhairva cycle continues to be practised under the

name Mahi SaSamvara in Nepal.13

This tantra is also referred along with the Trikalpa and Saptkalpa.

Tarantha credits Lalita Vajra with this tantra of 10th century.14 The

mantra is also referred to in Krsnayamaritantra 16-13 in an encoded

form and appears in full in 6. 1 3 ; 15 this mantra is also referred in

Vimalaprabha in the introduction to the Krsnayamaritantra on

Kalacakra tantra with a variant at the fourth quarter.16 The various

mantras found with different syllables in different texts of Hinduism

and Buddhism say that these mantras are the root mantra of the deity

Yamantaka.

These verses appear in Buddhist texts from Bali, but ironically no

iconographie descriptions of Yama/ Yamantaka occur in the TSS or the

M.P.17 Commenting on the thirty two syllable mantras , it is said that

the visualization of the deity should be learnt from one's preceptor.

The mantras of the deity's (Anga) organ found in M.P.18 refer to the

deity's deformed face, his dark ( Krsna ) colour speak of his nine faces

and reddish brown hair mass.19 In addition to the above mantras the

TSS and the M.P. include a few other mantras of Buddhist origin. These

mantras include fragments of typically Buddhist tantric offering

mantras. Invocation such as Namo Ratnarayana 's (Salution to the three

jewels) i.e., to the Buddha, the dharma, the Sangha, as well as epithets

employing the prefix Vajra indicate their Buddhist origin.

The Candasidhara mantra is for the destruction of evil demons

(Graha) which attack children. It is also inserted in MP in between

43.52 ab and ed. Its name itself denotes the edge of fierce sword. This

mantra is followed by another tantra Khadgaravana who is known as a

form of Siva, who is also addressed as Candesvara, Rudra. In Buddhist

texts this mantra invokes 'Candavajrapani', a fierce form of the Yaksa

Vajrapani.

Both the M.P. inserted into the ISP and the TSS incorporate

descriptions of Yamantaka originially as Buddhist deities along with

the procedures for their ritual worship which are included in Hindu

Tantra and Buddhist Tantrayana.

The mantras of Yamantaka appears in connection with a Yantra of

Yama used in the rites of black magic ( abhicara ), most likely the rite

of liquidation (marana). In the ritual applications of the MP and the

TSS both the names Yama and Yamantaka (elsewhere known as Yamari)

This content downloaded from

27.59.233.121 on Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient India 113

appear. Yamantaka and Kalantaka, "Deat

epithets of Yama, which were then transf

as "The ender of death." The cause of this confusion is that mantras of

the Buddhist Yamantaka were incorporated into a Yantra of Yama. The

first mantra is thirty-two syllable and the second twelve-fourteen or

ten syllable. -While the texts of the Yamantaka cycle of the Tibetan

Buddhist Tradition employ both of these mantras as mantras of

Yamantaka/ Yamari, the Hindu Tantric texts examined in this paper

identify the second mantra as mantra of Yama. The wording of the two

mantras , which continue to be recited by Tibetan Buddhists up to the

present do not indicate a connection to Tantric Buddhism. The first

one seems to be in praise of the enemy of Yama, who could be identified

either as Siva in his manifestation as Kalari (for the Hindus) or as

Vajrabhairava (for the Buddhists). The second mantra addresses the

(deity) with a face deformed (by fangs). The main texts of the

Yamantaka cycle in which these two mantras appear, are said to have

originated in Uddiyana. Uddhyana/ Oddiyana is normally identified

with a province in the Swat Valley in the north-west of the subcontinent,

present-day Pakistan, where tantrism once flourished. According to

the Hindu Tantras, the two mantras are said to be inscribed in the yantra

along with a third eight-syllabled mantra which cannot be identified in

the Buddhist texts examined in this paper. The third mantra is identified

as mantra of Yama. It appears in the texts such as the MP and the TSS

that they did not borrow the three mantras directly from Buddhist

Tantric texts, for example the Krsnayamaritantra , but rather from

another source which included their mantra.

The mantras of Yamanntaka's limbs ( anga ) listed in MP 47.11 +

address a dark deity with nine faces and reddish-brown hair. This

description suggests nine-faced form of the dark Yamantaka (cf. also

the references to his faces in MP 47.23+) who is identified as

Vajrabhairava. This nine-faced form of Yamantaka is not described in

the Krsnayamaritantra but in chapter 4 of the Vajramahabhairvatantra.

The question that arises is what attitudes the compilers of the MP

and the TSS had towards the Buddhist material they included. The

compilers of the MP and the TSS seem to have had an ambivalent

attitude. On the one hand, they describe the rites of black magic

( abhicara ) for use against the enemies of the (Vedic) dharma and Veda.

On the other hand, they incorporate mantras from these very enemies.

Unlike other groups in Hinduism who included the Buddha among

Visnu's aviaras , the compilers of these two texts made a distinction

between their own tradition and that of the Buddhists. The two

Yamantaka mantras are inscribed in Yantras. Since they were

transmitted as part of a ritual procedure which included the drawing of

This content downloaded from

27.59.233.121 on Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 14 IHC: Proceedings, 74th Session, 2013

a powerful yantra, they could not easily be omitted. In the case of the

other mantras to cure diseases, the compilers apparently did not want

to exclude popular mantras , which were believed to be powerful, even

though they carried traces of the Buddhist context from which they

were taken. Other mantras were inserted between descriptions of ritual

procedures for similar Hindu deities for the sake of completeness. The

description of Vasudhara, for example, precedes that of different forms

of Durga and is directly followed by the presentation of the mantras of

the traditional Hindu earth goddess Bhudevi. The description of

Jambhala is followed by that of Kubera. In the above discussed texts

the Buddhist deities do not occupy the positions of major deities.

Jambhala, Vasudhara and Yama are all associated with the Yaksa cult

as well as Vajragandhari, Vajrapani and possibly Vajrasrnkhala (if he

is the male counterpart of Vajrasrnkhala), whose names are invoked in

some of the mantras of Buddhist origin. Some of the mantras explicitly

invoke the lord of the Yaksas. In their subordinate positions they were

apparently not felt to interfere with the compilers' sectarian affiliation.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1 . A. Sanderson, Saivism and Tantric traditions ( Proceedings of world Relig

ed. S. Sutherland, P. Clarke and F. Hardy, Routledge, London, pp. 128-1 72.

2. M. de Mallmann, The Hindu Deities in Tantric Buddhism , Maisonneuve, Par

3. B. Bhattacharya, Buddhist Deities in Hindu Garb, Proceeding and Transactio

Indian Oriental Conference , University of Punjab, Lahore, 1930, 1277-1298

4. B. Bhattacharya, The Indian Buddhist Iconograpny , Based on Sadhanm

Cognate Tantric Texts of Rituals , Firma K.L.M., Calcutta, 1958, p.349.

5 . B. Bhattacharya, The Cult of Bhuttadharma, Proceedings and Transactions o

India Oriental Conference (Bihar and Orissa Research Society), Patna, 1 993

6. ISP Insansi vag G uru de v a Paddhati, Insansivag Gurudeva Paddhati by Insansiv

Mishra , edited by T. Ganapati Sastri. 4 Parts, Trivandrum University Press,

1920-1925.

7. Tantras Sara Sangraha (With Commentary) ed. by M.D. Aiyangar, Govt. Oriental

Manuscripts Library, Madras, 1950, 17.129). Mantrapada47; l-39(I'sanagurudevaPaddhti).

Agni Purana , 306.

8. Ibid.

9. Mantrapada 47: 1-39 ( Isanagurudeva Padhati).

10. Agni Purna 306.

11. TSS p.238 pg.lO.

12. Hookyas; op. cit., pp.204-205.

13. Decleer, 1998, p.296.

14. Taranatha, History of Buddhism ; Chattopadhyaya 170, p.243.

15. Krsnayamari tantra, p. 749.

16. Kolakra tantra 4.1 18.

17. Raghava Bhatta, p. 866. 25.

18. MP47.11 + .

19. Dwivedi, 1992, p. 42.

This content downloaded from

27.59.233.121 on Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- MandalaDocument2 pagesMandalarwerwerNo ratings yet

- AgamasDocument1 pageAgamastantratriggershivaNo ratings yet

- The Guhyagarbha Tantra: ART NE ART WODocument18 pagesThe Guhyagarbha Tantra: ART NE ART WOoceanic23No ratings yet

- Pran Band Ha MantraDocument1 pagePran Band Ha MantraSergio PereiraNo ratings yet

- The Akshaya Patra Series Manasa Bhajare: Worship in the Mind Part TwoFrom EverandThe Akshaya Patra Series Manasa Bhajare: Worship in the Mind Part TwoNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Contents of Abhinavagupta's Sri Tantraloka Vol. IXDocument9 pagesSummary of The Contents of Abhinavagupta's Sri Tantraloka Vol. IXMukeshNo ratings yet

- Works of Sri Sankaracharya 16 - Prakaranas 2Document302 pagesWorks of Sri Sankaracharya 16 - Prakaranas 2vrajasekharan100% (1)

- Safe & Simple Steps To Fruitful MeditationFrom EverandSafe & Simple Steps To Fruitful MeditationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sudarshan Kriya - Sri Sri Ravi Shankar - EEG During SKY.M BhatiaDocument3 pagesSudarshan Kriya - Sri Sri Ravi Shankar - EEG During SKY.M BhatiaMaxwell ButlerNo ratings yet

- Chapter TwentyDocument61 pagesChapter TwentyksampNo ratings yet

- Spiritual VisualizationDocument93 pagesSpiritual VisualizationemailNo ratings yet

- Eyes: Focus Your Eyes On The Tip of The Nose. Mudra: Bring Both Palms in Front of The Heart CenterDocument3 pagesEyes: Focus Your Eyes On The Tip of The Nose. Mudra: Bring Both Palms in Front of The Heart CenterCat BirdsongsNo ratings yet

- Experiencing The Original You - KundaliniDocument2 pagesExperiencing The Original You - KundaliniErica Yang100% (1)

- Tuning in Before Your Kundalini Yoga Practice: Sources: The Aquarian Teacher, Page 78, Pages 71-72Document3 pagesTuning in Before Your Kundalini Yoga Practice: Sources: The Aquarian Teacher, Page 78, Pages 71-72Nayaka Giacomo MagiNo ratings yet

- Confessions of An American Sikh, PDFDocument430 pagesConfessions of An American Sikh, PDFAmandeep singh100% (1)

- Wayman Alex TR Yoga of The GuhyasamajatantraDocument7 pagesWayman Alex TR Yoga of The GuhyasamajatantraHansang KimNo ratings yet

- Summary of Vol. VIII of Abhinavagupta's Sri Tantraloka and Other WorksDocument5 pagesSummary of Vol. VIII of Abhinavagupta's Sri Tantraloka and Other WorksMukesh100% (1)

- Tantra Terms & QuestionsDocument3 pagesTantra Terms & Questionsitineo2012No ratings yet

- Bhairava Stotra Shiva Stuti of Sri AbhinavaguptaDocument5 pagesBhairava Stotra Shiva Stuti of Sri AbhinavaguptaBanibrata BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Guru Ram Das & The Throne of Raj Yog - 3HO Kundalini Yoga - A Healthy, Happy, Holy Way of Life PDFDocument5 pagesGuru Ram Das & The Throne of Raj Yog - 3HO Kundalini Yoga - A Healthy, Happy, Holy Way of Life PDFRamjoti KaurNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument9 pagesBibliographyswainpiyush123No ratings yet

- Summary of Vol. VI of Abhinavagupta's Sri Tantraloka and Other WorksDocument5 pagesSummary of Vol. VI of Abhinavagupta's Sri Tantraloka and Other WorksMukeshNo ratings yet

- Kvaerne Per Bonpo Studies The A Khrid System of Meditation 2Document86 pagesKvaerne Per Bonpo Studies The A Khrid System of Meditation 2LuckyCoffeeNo ratings yet

- Vajrayogini Mandala WebsiteDocument1 pageVajrayogini Mandala WebsiteYuriNo ratings yet

- Guru Purnima Malar 2002 PDFDocument67 pagesGuru Purnima Malar 2002 PDFjayNo ratings yet

- Bhoot shuddhi technique awakens tattwas and siddhisDocument3 pagesBhoot shuddhi technique awakens tattwas and siddhisRakesh YadavNo ratings yet

- Human Consciousness and Gorakhnath's PhilosophyDocument5 pagesHuman Consciousness and Gorakhnath's PhilosophyalokNo ratings yet

- A Meditation For Couples - Kirtan Kriya To Clear The Clouds - KundaliniDocument2 pagesA Meditation For Couples - Kirtan Kriya To Clear The Clouds - KundaliniErica YangNo ratings yet

- Yogendranathyogiblogspotin Khechari VidyaDocument21 pagesYogendranathyogiblogspotin Khechari VidyaDebraj KarakNo ratings yet

- Mandala and Agamic Identity in The TrikaDocument25 pagesMandala and Agamic Identity in The TrikabejNo ratings yet

- Die Vedischen Zwillingsgotter: Untersuchungen Zur Genese Ihres Kultes. by GabrieleDocument3 pagesDie Vedischen Zwillingsgotter: Untersuchungen Zur Genese Ihres Kultes. by GabrieleYahia ChouderNo ratings yet

- Review of Stephen Hodge - The Maha Vairocana Abhisambodhi Tantra With Buddhaguhya's CommentaryDocument3 pagesReview of Stephen Hodge - The Maha Vairocana Abhisambodhi Tantra With Buddhaguhya's CommentaryAnthony TribeNo ratings yet

- Basic Breath Series 2 - IntermediateDocument5 pagesBasic Breath Series 2 - IntermediateNicole Hawkins100% (1)

- Ardhanarishvara Hymn with MeaningDocument7 pagesArdhanarishvara Hymn with Meaningdeepika soniNo ratings yet

- Pittra Kriya (TRADUCIR)Document2 pagesPittra Kriya (TRADUCIR)Sada Anand SinghNo ratings yet

- Article From Times of IndiaDocument3 pagesArticle From Times of IndiapsundarusNo ratings yet

- DvādaśāntaDocument2 pagesDvādaśāntaGiano Bellona100% (1)

- Adi Shakti Sant Mat 2012 FinalDocument42 pagesAdi Shakti Sant Mat 2012 FinalCadena CesarNo ratings yet

- Tara Astak, in English and TranslationDocument3 pagesTara Astak, in English and TranslationPradyot Roy100% (1)

- Atharvavedins in Tantric Territory in TH PDFDocument127 pagesAtharvavedins in Tantric Territory in TH PDFbabuNo ratings yet

- Cicuzza, C. - The Laghutantratika of Vajrapani (Reduced)Document167 pagesCicuzza, C. - The Laghutantratika of Vajrapani (Reduced)the CarvakaNo ratings yet

- BibbyDocument8 pagesBibbyjaya2504No ratings yet

- The Vairocana Bhisam Bodhi SutraDocument320 pagesThe Vairocana Bhisam Bodhi SutraBobby BlackNo ratings yet

- The Goddess Śśandrāmatā in Khotanese TextsDocument7 pagesThe Goddess Śśandrāmatā in Khotanese TextsStaticNo ratings yet

- Attune your mind and chakras with The Aquarian Sadhana mantrasDocument3 pagesAttune your mind and chakras with The Aquarian Sadhana mantrasYoga Soumaya RabatNo ratings yet

- Essence of Gheranda SamhitaDocument5 pagesEssence of Gheranda Samhitabuccas13No ratings yet

- Samalei To Sambaleswari - Ashapuri To Samalei: Dr. Chitrasen PasayatDocument9 pagesSamalei To Sambaleswari - Ashapuri To Samalei: Dr. Chitrasen PasayatBiswajit SatpathyNo ratings yet

- 2nd Sutra Meditation: Mandhavani Kriya - 3HO Kundalini Yoga - A Healthy, Happy, Holy Way of LifeDocument4 pages2nd Sutra Meditation: Mandhavani Kriya - 3HO Kundalini Yoga - A Healthy, Happy, Holy Way of LifeKrista BailieNo ratings yet

- Symbols of TantraDocument1 pageSymbols of TantraYugal ShresthaNo ratings yet

- An English Translation of The Mañjuśrī Nāma Sa Gīti J Its Origin and Historical Context Within The Jñānapāda TraditionDocument108 pagesAn English Translation of The Mañjuśrī Nāma Sa Gīti J Its Origin and Historical Context Within The Jñānapāda TraditionkingcrimsonNo ratings yet

- Schools and Branches of Tantra and NityaDocument49 pagesSchools and Branches of Tantra and Nityadrystate1010No ratings yet

- Skorupski, T. - Sarvadurgatiparisodhana Tantra (Vol. 2)Document146 pagesSkorupski, T. - Sarvadurgatiparisodhana Tantra (Vol. 2)the CarvakaNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Deities and Mantras in The Hind-37237397Document17 pagesBuddhist Deities and Mantras in The Hind-37237397Mike LeeNo ratings yet

- Deities 1Document32 pagesDeities 1Sandeep ElluubhollNo ratings yet

- Gudrun B Uhnemann - Buddhist Deites & Mantras in The Hindu TantrasDocument32 pagesGudrun B Uhnemann - Buddhist Deites & Mantras in The Hindu TantraspactusNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Society in Medieval Kumaon and Garhwal PDFDocument12 pagesAgrarian Society in Medieval Kumaon and Garhwal PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- The Beast Within' Race, Humanity, and Animality PDFDocument20 pagesThe Beast Within' Race, Humanity, and Animality PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Of Pigs and Parchment Medieval Studies and The Coming of The Animal PDFDocument8 pagesOf Pigs and Parchment Medieval Studies and The Coming of The Animal PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- ARTICLE Vol 43 44 1968 69Document8 pagesARTICLE Vol 43 44 1968 69anjanaNo ratings yet

- Bhadli Purana A Popular and Historical Source of Omens in Medieval Rajasthan PDFDocument8 pagesBhadli Purana A Popular and Historical Source of Omens in Medieval Rajasthan PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Women Labour in Medieval Aasham Slavery and Production System PDFDocument8 pagesWomen Labour in Medieval Aasham Slavery and Production System PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Water Bodies and The State - A Study in The Context of Ancient and Early Medieval Odisha PDFDocument11 pagesWater Bodies and The State - A Study in The Context of Ancient and Early Medieval Odisha PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Women Donors of Karnataka (9 - 13 Century Ad) - Issues of Gender and Faith PDFDocument8 pagesWomen Donors of Karnataka (9 - 13 Century Ad) - Issues of Gender and Faith PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Dharampur Mosque, Naogaon, Bngladesh and Its Inscriptions PDFDocument7 pagesDharampur Mosque, Naogaon, Bngladesh and Its Inscriptions PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Economic Contours of Hero's Den Untalked Dynamics of Gogamedi Shrine in Medieval Rajasthan PDFDocument6 pagesEconomic Contours of Hero's Den Untalked Dynamics of Gogamedi Shrine in Medieval Rajasthan PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- The Historical Significance of The Kalinkattupparani, A 12TH Century Tamil Text PDFDocument8 pagesThe Historical Significance of The Kalinkattupparani, A 12TH Century Tamil Text PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Folk Tradition of Sanskrit Theatre A Study of Kutiyattam in Medieval Kerala PDFDocument11 pagesFolk Tradition of Sanskrit Theatre A Study of Kutiyattam in Medieval Kerala PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Some Reflections On The Loss of Learning and Its Retrieval in The Wake of Twelve Years Drought PDFDocument9 pagesSome Reflections On The Loss of Learning and Its Retrieval in The Wake of Twelve Years Drought PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Shah Nahr Its History, Technology and Socio-Political Implications PDFDocument13 pagesShah Nahr Its History, Technology and Socio-Political Implications PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Irrigation System in Tumkur District An Epigraphic Study PDFDocument6 pagesIrrigation System in Tumkur District An Epigraphic Study PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Changing Contours of Social Geography in Kashmir From Nilamata Purana To Rajatarangini PDFDocument9 pagesChanging Contours of Social Geography in Kashmir From Nilamata Purana To Rajatarangini PDFanjana100% (1)

- Reflections of Plant Life in The Buddhist Sculptural Art of Amaravati PDFDocument6 pagesReflections of Plant Life in The Buddhist Sculptural Art of Amaravati PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Jaina Culture in Karimnagar District, Telengana - A Study PDFDocument12 pagesJaina Culture in Karimnagar District, Telengana - A Study PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Ugachchan or Kommigal - The Temple Drummers From Kēralam PDFDocument8 pagesUgachchan or Kommigal - The Temple Drummers From Kēralam PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Movements and Migration of Brahmanas in Andhra From Epigraphy (7TH-10TH Century Ce) PDFDocument9 pagesMovements and Migration of Brahmanas in Andhra From Epigraphy (7TH-10TH Century Ce) PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Locating South Eastern Bengal in The Buddhist Network of Bay of Bengal (C. 7 TH Century Ce-13 TH Century Ce) PDFDocument7 pagesLocating South Eastern Bengal in The Buddhist Network of Bay of Bengal (C. 7 TH Century Ce-13 TH Century Ce) PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Ownership of The Womb A Study of The Jatakas PDFDocument7 pagesOwnership of The Womb A Study of The Jatakas PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 27.59.233.121 On Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:20 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 27.59.233.121 On Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:19:20 UTCanjanaNo ratings yet

- Imaging The Rural Landscape of The Konkan Through The Land Charters of The Silāhāras. (C. Ad 8TH To 11TH Century) PDFDocument13 pagesImaging The Rural Landscape of The Konkan Through The Land Charters of The Silāhāras. (C. Ad 8TH To 11TH Century) PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Real Import of The Word 'Pura' and The Arya-Dasa Systems in The Rig Veda PDFDocument7 pagesReal Import of The Word 'Pura' and The Arya-Dasa Systems in The Rig Veda PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 27.59.233.121 On Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:13:48 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 27.59.233.121 On Thu, 24 Sep 2020 05:13:48 UTCanjanaNo ratings yet

- Bridal Mysticism and Gender The Woman's Voice in Virasaiva Vacanas PDFDocument11 pagesBridal Mysticism and Gender The Woman's Voice in Virasaiva Vacanas PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- The Early Puranas Representing The Supernatural Social Groups PDFDocument9 pagesThe Early Puranas Representing The Supernatural Social Groups PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- Ports and Port Towns of Early Odisha Text, Archaeology and Identification PDFDocument11 pagesPorts and Port Towns of Early Odisha Text, Archaeology and Identification PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- 100 Years of Indian CinemaDocument19 pages100 Years of Indian CinemaAvinash Dave86% (7)

- Sundara Kanda and Practical LessonsDocument8 pagesSundara Kanda and Practical LessonsJayakrishnaNo ratings yet

- B-Modelado Cinemático de Manipuladores Seriales Basado en Cuaterniones Duales LIBRO PDFDocument803 pagesB-Modelado Cinemático de Manipuladores Seriales Basado en Cuaterniones Duales LIBRO PDFeduardodecuba1980100% (1)

- Sai Baba GitaDocument244 pagesSai Baba Gitasathi2317411No ratings yet

- Teach Yourself Avesta LanguageDocument122 pagesTeach Yourself Avesta LanguageTur111No ratings yet

- Shabda Mac06Document24 pagesShabda Mac06runjuythNo ratings yet

- 2020 Srikanth CBIT CALENDERDocument1 page2020 Srikanth CBIT CALENDERKratika Sharma BhateNo ratings yet

- Advice On Bhagti (Meditation) From Guru Angad Dev Jee - TapobanDocument2 pagesAdvice On Bhagti (Meditation) From Guru Angad Dev Jee - TapobanAmarpreet Singh Anand KaurNo ratings yet

- Times of League - March - 2011Document11 pagesTimes of League - March - 2011muslimleaguetnNo ratings yet

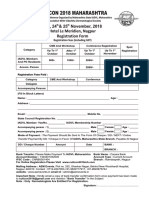

- Cuticon 2018 Maharashtra - Registration FormDocument1 pageCuticon 2018 Maharashtra - Registration FormManoj WaghmareNo ratings yet

- New Company ListDocument2,100 pagesNew Company Listsanket shah100% (1)

- Solar Bidders ListDocument10 pagesSolar Bidders ListSreekanth SunkeNo ratings yet

- Mahayana Buddhism BeliefsDocument32 pagesMahayana Buddhism BeliefsElla Bucud Simbillo100% (2)

- Venerable Master Hai Xian - A Modern Day Patriarch HuinengDocument11 pagesVenerable Master Hai Xian - A Modern Day Patriarch Huinengbc1993No ratings yet

- Sakyaraksita As Varahi AuthorDocument5 pagesSakyaraksita As Varahi AuthorqadamaliNo ratings yet

- Public AdministrationDocument2 pagesPublic Administrationtara12490% (1)

- Buses of Skeletal Routes On October 30 2019 For Staff MembersDocument1 pageBuses of Skeletal Routes On October 30 2019 For Staff MembersAnmol KumarNo ratings yet

- Re Editing PDFDocument49 pagesRe Editing PDFNadsNo ratings yet

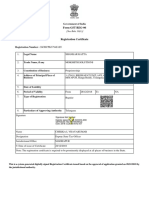

- GST CertificateDocument3 pagesGST Certificatekatta shankarNo ratings yet

- Mahabharat Retold With Scientific EvidencesDocument39 pagesMahabharat Retold With Scientific EvidencesVenkatapathy Subramanian100% (2)

- Konchog Chidu PracticeDocument15 pagesKonchog Chidu PracticeEijō Joshua89% (9)

- Shiv March 13Document6 pagesShiv March 13Shailesh ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Bhakti Movement in Reference To Chaitanya Mahaprabhu in The Built Environment of Gouranga para of KatwaDocument12 pagesInfluence of Bhakti Movement in Reference To Chaitanya Mahaprabhu in The Built Environment of Gouranga para of KatwaRishiraj GhoshNo ratings yet

- Rels ReflectionDocument8 pagesRels Reflectionapi-239845986No ratings yet

- KA Table 4 Constituents of Urban Agglomerations Having Population 1 Lakh Above Census 2011Document3 pagesKA Table 4 Constituents of Urban Agglomerations Having Population 1 Lakh Above Census 2011savithaveetha6875No ratings yet

- Performing Duty with DetachmentDocument6 pagesPerforming Duty with DetachmentCelestial ProphecyNo ratings yet

- Justice Syed Mahmood M HidayatullahDocument6 pagesJustice Syed Mahmood M Hidayatullahzeeshan_amuNo ratings yet

- Mistry DipakDocument2 pagesMistry Dipakkukadiya127_48673372No ratings yet

- First Applicant Name and Address ListDocument67 pagesFirst Applicant Name and Address ListYASH DAHIYANo ratings yet

- Avataras or Incarnations of Lord Visnhu: MatsyavataraDocument6 pagesAvataras or Incarnations of Lord Visnhu: MatsyavataraMeda ParmikoNo ratings yet

- No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingFrom EverandNo Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (173)

- When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult TimesFrom EverandWhen Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult TimesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind: Informal Talks on Zen Meditation and PracticeFrom EverandZen Mind, Beginner's Mind: Informal Talks on Zen Meditation and PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (72)

- My Spiritual Journey: Personal Reflections, Teachings, and TalksFrom EverandMy Spiritual Journey: Personal Reflections, Teachings, and TalksRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (26)

- Think Like a Monk: Train Your Mind for Peace and Purpose Every DayFrom EverandThink Like a Monk: Train Your Mind for Peace and Purpose Every DayRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1026)

- Summary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for LivingFrom EverandThe Art of Happiness: A Handbook for LivingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1205)

- Dancing with Life: Buddhist Insights for Finding Meaning and Joy in the Face of SufferingFrom EverandDancing with Life: Buddhist Insights for Finding Meaning and Joy in the Face of SufferingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (25)

- Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist PerspectiveFrom EverandThoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist PerspectiveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (136)

- How to Stay Human in a F*cked-Up World: Mindfulness Practices for Real LifeFrom EverandHow to Stay Human in a F*cked-Up World: Mindfulness Practices for Real LifeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (11)

- Buddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomFrom EverandBuddha's Brain: The Practical Neuroscience of Happiness, Love & WisdomRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (215)

- Don't Just Do Something, Sit There: A Mindfulness Retreat with Sylvia BoorsteinFrom EverandDon't Just Do Something, Sit There: A Mindfulness Retreat with Sylvia BoorsteinRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- Mahamudra: How to Discover Our True NatureFrom EverandMahamudra: How to Discover Our True NatureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- An Appeal to the World: The Way to Peace in a Time of DivisionFrom EverandAn Appeal to the World: The Way to Peace in a Time of DivisionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- The Tibetan Book Of The Dead: The Spiritual Meditation Guide For Liberation And The After-Death Experiences On The Bardo PlaneFrom EverandThe Tibetan Book Of The Dead: The Spiritual Meditation Guide For Liberation And The After-Death Experiences On The Bardo PlaneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Buddhism Is Not What You Think: Finding Freedom Beyond BeliefsFrom EverandBuddhism Is Not What You Think: Finding Freedom Beyond BeliefsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (127)

- Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a BuddhaFrom EverandRadical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a BuddhaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (375)

- One Dharma: The Emerging Western BuddhismFrom EverandOne Dharma: The Emerging Western BuddhismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- Buddhism 101: From Karma to the Four Noble Truths, Your Guide to Understanding the Principles of BuddhismFrom EverandBuddhism 101: From Karma to the Four Noble Truths, Your Guide to Understanding the Principles of BuddhismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (78)

- The Art of Living: Peace and Freedom in the Here and NowFrom EverandThe Art of Living: Peace and Freedom in the Here and NowRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (832)

- The Meaning of Life: Buddhist Perspectives on Cause and EffectFrom EverandThe Meaning of Life: Buddhist Perspectives on Cause and EffectRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (59)