Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Factors Behind Police Performance in the Philippines

Uploaded by

PJr MilleteOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Factors Behind Police Performance in the Philippines

Uploaded by

PJr MilleteCopyright:

Available Formats

WORKING PAPER

Diagnosing Factors behind Officers’ Performance

in the Philippine National Police

Ronald U. Mendoza, PhD

Ateneo School of Government

Emerald Jay D. Ilac

Ateneo de Manila University – School of Social Sciences

Ariza T. Francisco

Ateneo School of Government

Jelo Michael S. Casilao

Ateneo School of Government

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

ATENEO SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT WORKING PAPER SERIES

Diagnosing Factors behind Officers’ Performance

in the Philippine National Police

Ronald U. Mendoza, PhD

Ateneo School of Government

Emerald Jay D. Ilac

Ateneo de Manila University – School of Social Sciences

Ariza T. Francisco

Ateneo School of Government

Jelo Michael S. Casilao

Ateneo School of Government

March 2020

The Ateneo School of Government would like to thank the Philippine National Police and

the Bless Our Cops Movement, Inc. for their generous support in the conduct of this study.

The Ateneo School of Government would also like to acknowledge the contributions and

support of Mark Robert Baldo, Sarah Jane Fabito, and Ivyrose Baysic.

This working paper is a draft in progress that is posted online to stimulate discussion and

critical comment. The purpose is to mine reader’s additional ideas and contributions for

completion of a final document.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views

of Ateneo de Manila University and the European Union.

Corresponding author:

Ariza T. Francisco, Ateneo School of Government

E-mail: afrancisco@ateneo.edu

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Abstract

The Philippine National Police (PNP) faces myriad challenges, spanning governance, corruption

and national security threats. Hence, securing a strong leadership pipeline equipped not only to

face these challenges, but also to strengthen policing effectiveness and over-all security sector

reforms is crucial. This study aims to map out some of the main factors that both build or erode

key leadership qualities and performance in the PNP. Using quantitative and qualitative methods,

the study examines four main factors, namely personality traits, organizational culture,

demographic profile and professional history, as predictor of performance for officers in the

National Capital Region. It finds evidence that personality traits, specifically openness,

agreeableness and neuroticism, as well as number of transfers, area of assignment, training on

managerial skills, age and education level are all factors for good performance for officers in the

PNP National Capital Region Police Office. These results emphasize the importance of training

and mentoring components in preparing young officers and recruits for the rigors of service. It

also underscores the need for a deeper analysis of recruitment and selection policies, to ensure

that the PNP successfully attracts the strongest candidates with the right leadership

characteristics and building blocks for service.

Keywords: police performance, Philippine National Police, personality, organizational culture

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

1. INTRODUCTION

Successfully recruiting and developing its leaders is a core challenge in many public and private

organizations. On top of this, for security sector organizations worldwide, governance and anti-

corruption challenges are often part and parcel of ongoing reforms to strengthen policing

effectiveness and over-all security sector reforms. For the Philippine National Police (PNP), these

aforementioned challenges are amplified for several reasons. For example, there are longstanding

governance challenges related to the promotion of personnel in the police force. In particular, there

are various groups typically influencing and shaping the careers of officers in the PNP. These

include senior officers themselves trying to take care of the careers of junior officers who have

worked with them, as well as local government officials have worked extensively with these

officers.1 Such influence could help mold some of the best leaders in the PNP, if they end-up

working well with development- and good-governance-oriented local government leaders and

senior police officials.

However, this very same “partnership” could be corrosive to the public good, if the PNP and local

governments are crippled by malgovernance, corruption and poor leadership. Young officers and

new recruits assigned to work in badly governed local jurisdictions and police units can quickly

be compromised and pick up bad habits from different stakeholders, including their own superiors

in the PNP as well as other government officials (Batalla, 2019). In fact, the PNP is “captured” in

some local jurisdictions where local politicians have in fact co-opted them to serve in their private

armed groups.2 A recent study found that election years are crucial turning points for fatal police

violence in several provinces and cities in the Philippines, suggesting an important role played by

local politicians in shaping police practices and behaviors (Kreuzer, 2018).

Combined with the challenges of modern community policing which requires not only political

savviness but adaptability to new technologies that could enhance security and police work, the

PNP also faces the persistent national security risks linked to factionalization and rebellion, and

1 These local government officials have, over time, developed extensive influence on the careers of different officers,

notably as part of their collaborative roles under the 1991 Local Government Code.

2 One of the most glaring examples of this is the participation of PNP personnel in the murder of 58 Filipino citizens,

including 53 journalist, in Maguindanao in 23 November 2009. At least 5 police officers would later be convincted,

along with the masterminds from the Ampatuan political clan. For details, the full decision can be accessed here:

https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/12/19/19/read-full-decision-on-maguindanao-massacre-case.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 2

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

threats of terrorism and violent extremism. Clearly, the institution faces myriad challenges in the

Philippine context, emphasizing even further the importance of strong integrity and skills in its

leadership pipeline.

The study aims to map out some of the main factors that either build or erode key leadership

qualities in the PNP. In particular, the study will rigorously diagnose the main incentives and

disincentives involved in leadership behaviors deemed critical to the effectiveness of the PNP.

Specifically, the diagnosis will examine:

a. The personality factors influential in police performance;

b. The quality of organization culture relevant in police performance;

c. The demographic facets connected to police performance;

d. The relation of professional history to police performance; and,

e. The combination of these factors leading to police performance.

This study will use quantitative and qualitative methods to examine the abovementioned links; and

it will draw on a comprehensive dataset of police officers in the National Capital Region (NCR).

It finds empirical evidence that personality traits, specifically openness, agreeableness and

neuroticism, as well as number of transfers, area of assignment, training on managerial skills, age

and education level are all factors for good performance for officers in the PNP National Capital

Region Police Office. The qualitative analysis and discussions revealed the importance of training

and mentoring, as well as avenues for identifying and strengthening subcultures that support

integrity and good performance among police officers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the

first comprehensive empirical assessment of performance of officers in the PNP. The goal is to

build on this first study in advancing continued governance and evidence-based institutional

reforms for the organization.

We noted here that the study team committed to full confidentiality protocols in order to protect

the identities of the officers. Only broad patterns and anonymized responses are analyzed and

reported in this study.

In what follows, section 2 briefly synthesizes the relevant literature, while section 3 elaborates on

the methodology behind this study. Section 4 discusses the empirical results, drawing on both the

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 3

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

quantitative and qualitative analyses. A final section outlines the main conclusions and policy

recommendations from this study.

2. REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE

The study employs Kurt Lewin’s Field Theory. It stipulates that any observable behavior is a by-

product of the interaction of the persona of the individual operating within a specified environment

or context. Lewin emphasized the study of behavior as a function of the total physical and social

situation. A brief review of the literature emphasizes some of the main factors to consider, namely

personality traits, or the individual characteristics; organizational culture, or the way the person

perceived the culture within the confines of the organization; demographic profile and professional

history.

2.a. Personality Traits

Balch (1972) describes personality traits as a set of characteristics that help shape the mentality of

police officers. In fact, a model of personality called the Five-Factor Model (FFM) has emerged

as a useful predictor of job performance over the last three decades (Al-Ali, 2011; Cochrane et al

2003). Also, known as the “Big Five” personality dimensions, the FFM consists of Openness to

experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (OCEAN). A key

study by Barrick and Mount (1991) contributed greatly toward validating the potency of the FFM

in predicting job performance. By conducting a meta-analysis of 117 studies, they found that the

FFM is a robust and meaningful framework for testing hypotheses relating individual personalities

to a wide range of criteria. Notably, they found that the Conscientiousness dimension was a valid

predictor of job performance for all types of occupational groupings, i.e., professionals, police,

managers, sales, and skilled/semi-skilled workers. They asserted that “those individuals who

exhibit traits associated with a strong sense of purpose, obligation, and persistence generally

perform better than those who do not.”

Another study of the Abu Dhabi Police supports that personality is a predictor of performance (Al-

Ali, 2011). They found that, of the Big Five, Conscientiousness and Extraversion showed positive

significant correlation with job performance. Neuroticism, on the other hand, showed significant

negative correlation with job performance. Furthermore, the study found that three of the FFM

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 4

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

have significant negative correlation with measurements of counterproductive work behavior

(CWB). In contrast, neuroticism showed positive associations with CWB. Finally, Sanders (2003)

noted that the international literature examining police officers’ performance appear to consistently

identify personality traits like intelligence, honesty, common sense, reliability and/or

conscientiousness.

2.b. Organizational Culture

Denison (1995) refers to organizational culture as an evolved context of organizational climate

where it is deeply rooted in history and is complex for direct manipulation. Further, they

characterize culture to include underlying traits and value dimensions (Denison and Mishra, 1995).

In one of their studies, a theoretical framework was developed for relating organizational culture

and effectiveness. Based on their study, they identified four (4) culture traits that relate to

effectiveness of the professional individual: Adaptability, Mission, Involvement, and Consistency.

They found out that involvement and adaptability were strong predictors of growth--that is,

individuals have the growing capacity to operate under the conditions of autonomy and have a

high resistance to change and adaptation. Further, the results showed that mission or long-term

vision and consistency are also positively related to effectiveness. This indicates that if the culture

of the organization was perceived stable and predictable over time, then this too contributes to

better performance of individuals working in that organization.

Organizational culture has been a dominant concept used to encapsulate the effect of the

environment on individual performance and collective effectiveness. It consists of what people

believe about how things work in their organizations and the behavioral and physical outcomes of

these beliefs (Sinclair, 1993). Recent studies on the PNP analyzes the organization’s systemic

corruption (Batalla, 2019) and violence (Kreuzer, 2018). Batalla (2019) examines the

institutionalized corruption at the PNP, which may be rooted in patronage politics, weak internal

controls, and culture of favoritism and protection (known as kuya system or bata-bata system).

On the other hand, patterns of lethal police violence vary in Metro Manila, wherein Quezon City

and Manila City have the highest rate at almost identical rates of 14.5 killings per million

population annually, while Pateros and San Juan City both have no reported killings (Kreuzer,

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 5

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

2018). This suggests that police performance may be greater influenced by specific local

subcultures.

It is possible to link an entirely separate branch of literature—focused on institutions—to the

growth of the organizational culture. For instance, research by Jiao (2010) examines differences

in the institutional innovations for combatting corruption by the Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF)

and New York Police Department (NYPD). HKPF routinely partners with an independent anti-

corruption agency, ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption), 3 while the NYPD has

established internal integrity mechanism through its Internal Affairs Bureau (IAB).4 This suggests

a diversity in institutional designs which balances the internal and external accountability

mechanisms germane to different police agencies across countries.

2.c. Demographic Profile

Demographic profile pertains to age, gender, marital status, and academic background. Studies

show how these various dimensions can also influence individual performance. In terms of age,

older adults have difficulty with the mastery of training content and completion of tasks when

compared to younger adults (Kubeck et al., 1996). Another study explained how physiological

aging can result in a decline in basic cognitive and psychomotor abilities. However, older workers

demonstrate greater tendency for higher commitment, lower turnover, and voluntary absenteeism

(Rhodes, 1983).

Studies on gender revealed that male officers reported more hypermasculine values. These found

to be related to more citizen rudeness and an increased likelihood of receiving complaint report

(Schuck, 2014). In terms of civil status, married individuals revealed to differ significantly from

single individuals in relation to work values, where married individuals demonstrated high work

values and performance (Rueda and Ohzono, 2013). On the other hand, studies on the number of

children revealed that individuals with more young children tends to perform poorly because of

increased family responsibilities (Crouter, 1984).

3https://www.icac.org.hk/en/home/index.html

4 https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/bureaus/investigative/internal-affairs.page

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 6

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Educational attainment also shows that individuals with higher levels of education perform better

compare to less educated individuals (Aamodt, 1997). Apart from educational attainment, Henson

et al (2010) also observed that measures of police academy performance and civil service exam

score were linked to job success for police officers in a Midwestern police department he examined

during the period from 1996-2006.

2.d. Professional History

Professional history refers to the exposure of the police officer within the organization. In

particular, this relates to their areas of assignment, number of transfers, years of service, trainings

received, among other factors. There is a dearth of literature that would support professional

history as predictor of performance. For instance, studies found that length of work or tenure has

direct effect on degree of job knowledge and well-practiced work skills, which in turn positively

affect performance (Schmidt et al., 1986; McDaniel et al., 1988). International research also

identified age (which may also proxy for experience in the workforce) as one of the factors that

appear associated with better performance of police officers (e.g. Kubeck et al 1996; White 2008).

Ng & Feldman (2010) presented a contradictory position by suggesting that organizational tenure

had a decreasing impact on performance. Specifically, they found that tenure had a significant

impact on performance between 3 and 6 years in the organization—and this decreases until around

14 years in the organization. Furthermore, research on police misconduct also find empirical

evidence that prior criminal involvement, employment problems either with the police force or

with an earlier employer, complaints by citizens, and weaker education are among the warning

signs that end up predicting dismissals (e.g. Frank 2009; Kane and White 2009; Stinson et al 2012).

3. METHODOLOGY

Building on methods established in the literature, the empirical analysis herein utilizes a unique

micro-level dataset drawn from surveys, FGDs, and administrative information involving officers

of the PNP National Capital Region Police Office (PNP-NCRPO).

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 7

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

3.a. Participants

“Strong” performing police officers are defined as the police officers who have received awards

and those with zero cases filed against them. Awards include Medalya ng Kabayanihan, Medalya

ng Kadakilaan, Medalya nf Kagalignan, Medalya ng Kagitingan, Medalya ng Katapangan,

Meritorious Awards, and Metrobank Award. “Poor” performing police officers are those who have

legal, administrative and civil cases involving grave offenses, and with no or minimal awards.

Examples of grave offenses are drugs, human rights violations, robbery or extortion, and graft or

malversation. Information on awards and cases were derived from administrative information

provided by the PNP.

The sample was selected from the pool of current officers in the PNP National Capital Region

Police Office (NCRPO), a division of the Philippine National Police which has jurisdiction over

Metro Manila, also known as the National Capital Region. These officers rank from Patrolman to

Lieutenant Colonel, and who have been in active police service for the past 10 years (2009-2019).

This excludes those who died, dismissed, resigned, or retied in the past five years, and who were

recruited from 2015 to 2018. The total population of NCRPO is 23,144. Of this group, a total of

13,220 officers have awards, while 9,924 have cases. These were then stratified for proper

representation among districts in NCRPO (National Capital Region Police Office Headquarters,

Eastern Police District, Manila Police District, Northern Police District, Quezon City Police

District, and Southern Police District). The study participants were selected through electronic

randomization.

3.b. Sources of Data

This study draws on both quantitative and qualitative data using mixed methods.

Quantitative Survey. A total of four hundred seventy-nine (479) respondents participated in the

pen-and-paper quantitative survey. Of this, two hundred ninety-two (292) came from those tagged

as strong performing police officers, while one hundred eighty-seven (187) came from those

tagged as poor performing police officers. These numbers permit generalizability of results

following acceptable statistical criteria of 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval within

the total officers of the National Capital Region (NCRPO). The quantitative survey involved two

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 8

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

tests. The first was the OCEAN personality test and the second was an organizational culture

survey tool created by Denision and Mishra (1995). Both these surveys were implemented from

August to September 2019.

Personality Test. The OCEAN personality test is a 60-item questionnaire with factors measuring

openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. This test aims to

measure personality factors intrinsic to the individual. It has a reliability measure of 0.90, 0.78,

0.76, 0.86 and 0.90 for the dimensions of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and

conscientiousness, respectively. The factor descriptions are as follows:

A. Openness focuses on the intellect or imagination. This reflects how a person is willing to

try out new things, thinking out of the box, having varied interests, being daring and bold,

creative and curious.

B. Conscientiousness reflects how an individual controls his or her impulses, acts in socially

acceptable ways, and plans and organizes activities. It shows their self-discipline,

persistence, reliability, diligence, consistency, and thoroughness.

C. Extraversion looks at how a person interacts with other people. Specifically, this focused

on their level of social confidence, energy levels, ability to talk to anyone, assertiveness,

and friendliness.

D. Agreeableness seeks to showcase behaviors that demonstrate how an individual gets along

with other people, such as showing helpfulness, patience, tactfulness, loyalty, sensitivity

to others, politeness, and kindness.

E. Neuroticism measures an individual’s emotional stability and self-esteem. High

neuroticism leads to behaviors such as being moody, jealous, unconfident, insecure,

nervous, and unaccepting of criticism. 5

Organizational Culture Survey. The second tool was the organizational culture survey drawing on

seminal work by Denision and Mishra (1995). This is composed of four parts, and each part has

three different subparts. It was measured using a 5-point Likert scale and had internal reliability of

0.97. The factors of the test are as follows:

5 Further information on the OCEAN personality test could be obtained from

https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newCDV_22.htm.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 9

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

A. Involvement – reflects the engagement of individuals in the organization and its internal

dynamics. Involvement plays a key role in creating a sense of ownership and responsibility,

which in turn fosters a greater commitment to the organization and a growing capacity to

operate under conditions of autonomy (Denison and Mishra, 1995).

a. Empowerment – reflects the members’ sense of authority, ownership,

responsibility, initiative, and ability to manage their own work.

b. Team orientation – looks at how members of the organization are working

cooperatively towards common goals, and are reliant on team effort to get work

done.

c. Capability development – seeks to see how the organization develops employees’

skills to stay competitive.

B. Consistency – reflects the values, processes and systems that show an internal and stable

focus for the entire organization. Consistency refers to the degree of normative integration.

Its positive relation to effectiveness is underpinned by the hypothesis that an implicit

control system based on internalized values can be more effective in achieving integration

rather than on explicit rules and regulations. One negative aspect of highly consistent

cultures is the high resistance to change and adaptation (Denison and Mishra, 1995).

a. Core values – reflects how members share a set of values which create a sense of

identity.

b. Agreement – looks at how members are able to agree on critical issues and reconcile

differences.

c. Coordination and integration – seeks to see how the various functions and units of

the organization work well together to achieve common goals.

C. Adaptability – reflects how the organization adjusts to the public, learn new skills, or

change in response to an external demand. This positively relates to organizational

effectiveness (Denison and Mishra, 1995).

a. Creating change – reflects how the organization creates adaptive ways to meet

changing needs, reacts quickly to current trends, and anticipates future changes.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 10

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

b. Customer focus – looks at how the organization understands and reacts to the

public, and its concern to satisfy the public needs.

c. Organizational learning – seeks to translate signals from outside into opportunities

for innovation, knowledge, and capabilities for the organization’s growth.

D. Mission – reflects the purpose and direction of the organization and its members. Sense of

Mission or long-term vision also positively relates to effectiveness. This hypothesis was

based on their observation of several organizations that proved effective because they

pursued a mission combining economic and non-economic objectives, which provided

meaning and direction to its members (Denison and Mishra, 1995).

a. Strategic direction and intent – reflects how organization’s strategic intention and

purpose are defined, and clarify how everyone can contribute.

b. Goals and objectives – looks at the how the goals and objectives of the various units

are linked to the mission and vision, and provide everyone with a clear direction.

c. Vision – seeks to see the organization’s view of a desired future state, providing

overall guidance and direction.

Focus Group Discussions. FGDs were conducted in order to validate the results from the survey

and dig deeper into the underlying motivations behind some of the responses. Two FGDs were

conducted on August 27 and August 29, 2019, immediately after the pen-and-paper testing. The

FGDs were divided into two groups: the first group was composed of eight (8) police officers who

are facing administrative cases, while the second group was composed of ten (10) police officers

who received awards. A guide was specifically developed for the focus group discussions. This

guide asked questions pertaining to: a) describing the ideal police officer, b) factors that will help

these officers to do the ideal role, c) characteristics of poorly performing police officers, d) reasons

for their poor performance, and e) how the PNP as an institution creates these police officers

whether good or not.

Personal Data Sheet. Aside from the information gathered from the quantitative survey and the

FGDs, the study team was given access to personal data sheets in order to provide information on

the demographic profile of the participants and their professional history. The demographic profile

of the participants included the following information: age, gender, civil status, number of

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 11

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

children, educational attainment, religion, and the province where they originated. Meanwhile,

professional history of the participants included data on their tenure, respective areas of

assignment, and type of trainings they received, specifically on operational skills and managerial

skills. The study team committed to full confidentiality protocols in order to protect the identities

of the officers. Only broad patterns and anonymized responses are analyzed and reported in this

study.

3.c. Empirical Analysis

As for the quantitative analysis of the survey, multiple linear regression was implemented to assess

which factors contribute to the performance of the police officers. This was done by using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Content and thematic analyses were conducted

to make sense of the data collected from the focus group discussions. These involved coding all

the responses and then collating them into general themes. These themes were then reviewed,

defined, and labeled to describe the content of the data. To ensure accuracy of analysis, inter-coder

reliability was implemented wherein other qualitative analysts collaborated in reviewing the

transcripts and identifying the themes, as well as the description for each theme. Frequency of the

verbatim statements per general theme was also computed.

4. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

The empirical methodology draws on Kurt Lewin’s Field Theory, posited as B = f(p,E). This

theory stipulates that any observable behavior is a by-product of the interaction of the persona of

the individual operating within a specified environment or context. As such, applying this to the

PNP, performance can be understood as a result of the combination of an individual’s intrinsic

facets as operating within the context of the PNP. With this in mind, the study examined both the

intrinsic facets and the environmental or contextual factors that will shape performance for the

police force.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 12

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

4.a. Descriptive Analysis

As mentioned, there were a total of 479 participants in the study. Of these, 292 were those awarded

with various medals, and 187 received administrative sanctions. The average age of the

participants was 37 years old, and a majority were male (90.2%). In addition, 68.5% were married

and had on average 2 children. Of the total pool, 81.2% were Roman Catholic in religion, and 98%

completed up to college with the remaining 2% moving further into post-graduate studies.

On average, out of the total participant base, 62.6% came from Metro Manila and had worked with

the PNP for 12 years. They had been transferred precincts at least 3 times within their career. The

following table (Table 1) shows the division according to police districts of the total participant

base.

Manila Police District 24.80%

Quezon City Police District 19.80%

Southern Police District 18.60%

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 13

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

NCR Police Office 15.70%

North Police District 10.00%

Eastern Police District 9.80%

Table 1. Division of participants per police district

The 479 participants came from 252 different academic institutions, with 68% of the officers

earning with a degree in Criminology. Table 2 shows an anonymized list of the top schools that

are feeders of the police officers for the PNP. This illustrates that some schools are potentially

more able to produce recruits that will be strong performers.

Name of School Total Poor Strong

Performing Performing

N % N %

School A 100 47 47.0 53 53.0

School B 18 6 33.3 12 66.7

School C 11 5 45.5 6 54.5

School D 9 6 66.7 3 33.3

School E 9 3 33.3 6 66.7

School F 7 3 42.9 4 57.1

School G 7 3 42.9 4 57.1

School H 7 2 28.6 5 71.4

School I 6 3 50.0 3 50.0

School J 6 3 50.0 3 50.0

School K 4 0 0.0 4 100.0

Table 2. Top Schools where NCRPO cops graduated

The descriptive analysis allows for testing associations between variables and performance. Table

3 and Table 4 below shows the results of the descriptive analysis on demographic profile and

professional history, respectively.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 14

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Age Younger officers aged 20-29 are associated to poorer performance.

This coheres with literature citing age (which is also a proxy for

experience) is related to higher degree of job knowledge, higher

commitment and lower turnover (Kubeck et al., 1996; Rhodes, 1983).

Gender Male officers are significantly associated to poor performance. This

supports existing international studies that found male officers

reported more hyper-masculine values, which are related to more

citizen rudeness and an increased likelihood of receiving a complaint

report (Schuck, 2014).

Civil Status Married officers have significantly higher percentage of poor

performers. Interestingly, this result contradicts existing literature that

revealed married individuals differ significantly from single

individuals in relation to work values, where married individuals

demonstrated high work values and performance (Rueda and Ohzono,

2013). Here, the civil status variable may be influenced by number of

children, where married individuals are more likely to have more

children (see below).

Number of Officers with more children have significantly higher number of poor

children performances. This aligns to prevous studies that found officers with

higher number of young children are more at risk to eliciting bad

performance due to heavier family responsibilities (Crouter, 1984).

Educational Educational attainment is associated with strong performance. This

attainment coheres with numerous studies that found better-educated officers

perform better in the academy, receive higher supervisor evaluations

of job performance, have fewer disciplinary problems and accidents,

are assaulted less often, use force less often, and miss fewer days of

work than their less educated counterparts (Aamodt, 1997).

Religion The proportion of poor and strong performers among different

religions were not significant.

Originating There is no significant difference in performance between officers

Province from Metro Manila and non-Metro Manila.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 15

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Table 3. Descriptive analysis of demographic variables

Area of Area of assignment is associated to performance. Specific districts are

Assignment more likely to produce poor performers.

Number of The number of transfers is associated to performance. The more an officer

Transfers is transferred to different stations, the higher likelihood for better

performance.

Years of Service Officers with 1-10 years of service are more likely to be poor performers.

This supports studies conducted that found length of work has direct

effect on degree of job knowledge, which in turn positively affect work

performance (Schmidt et al., 1986).

Training Trainings were categorized into operationsl skills and managerial skills.

received Officers who underwent managerial skills training, not just operational

skills, are more likely to be strong performers.

Table 4. Descriptive analysis of professional history variables

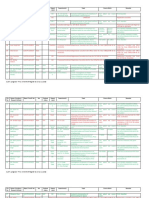

4.b. Regression Analysis

The multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine predictors of both strong and poor,

focused on examining personality traits, perceived organizational culture, professional history, and

demographic profile. This study finds evidence that personality traits, specifically openness,

agreeableness and neuroticism, as well as number of transfers, area of assignment, training on

managerial skills, age and education level are all factors for strong performance for officers in the

PNP National Capital Region Police Office (See Table 1 in the Appendix for regression results

table).

Strong performing police officers. For the police officers who received awards, the personality

facets of Neuroticism ( = -.155, p=.031), Openness ( = -.199, p=.006), and Agreeableness ( =

-.145, p=.051) were found to be predictors of good performance. This means that the police

officers who score lower on these facets were found to have a stronger personality aligned to the

organizational culture and perform better. They are more intrinsically driven to succeed rather than

be influenced by other individuals. These are individuals who prefer routine and tried-and-tested

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 16

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

methods rather than new ideas. In addition, they act more independently of others, remain firm on

their stance, demonstrate confidence and have lower self-doubt.

On the other hand, cultural facets from the Denison survey, specifically mission ( = -.046,

p=.619), adaptability ( = -.020, p=.807), involvement ( = .043, p=.630) and consistency ( = -

.018, p=.858), were found to be weak predictors of good performance. This signified that the

perceived organizational culture was not a major influence for the good performing police officers.

This could be because these officers were more intrinsically driven rather than externally

motivated to perform well.

Looking at their professional history, the empirical results showed a significant direct relationship

between number of transfers ( = .535, p=.000), area of assignment ( = -.228, p=.000) and

training on managerial skills ( = .569, p=.000) and performance. More transfers for a police

officer were associated with a higher likelihood that the police officer would perform better.

Consistently, the findings showed that assignment in certain districts negatively predicted good

performance. Quezon City and Manila City have significantly higher number of poor performing

officers among the 17 NCR cities and municipality. Similarly, another study shows that these two

cities have the highest fatal police encounters per capita from 2006 to 2015 (Kreuzer, 2018). This

result cohered with the longstanding policy to encourage rotations in different assignments for

police officers. From a governance perspective, this also cohered with the effort to prevent officers

from being “captured” through corrupt transactions whose risk tends to increase with more

familiarity in an assignment. Rotations help to prevent over-familiarization with potentially

corrupt elements in any one assignment, and it also provides police officers with the opportunities

to exhibit performance and gain more experience in different assignments. Plum assignments are

also more evenly distributed so that more officers are given a chance to distinguish themselves.

Lastly, those officers who received managerial skills training, not just operational skills training,

have higher likelihood to perform better. This suggests that leadership development has a key role

in fostering good performance.

Age ( = .269, p=.000) and education ( = .115, p=.046) were both associated with good

performance as well. This suggested the greater risks of poor performance were frontloaded in a

young officer’s career, when experience and education had not yet become influencing factors.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 17

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Poor performing police officers. For the police officers who were given administrative cases, none

of the personality facets in the OCEAN test were found to be predictors of their poor performance.

This means that for this group, their performance was not intrinsically driven. More likely,

performing under par was a result of their interaction with the environment they operated in.

Cultural facets from the Denison survey indicated however that organizational culture was not also

predictive of their poor performance. This meant that the poor performance of the police officers

was not influenced by the organizational culture itself, but by the interaction among members of

the organization. This could be with fellow police officers or their respective leaders. This angle

would later be validated during the FGDs as officers mentioned the “bata-bata system” whereby

senior officers and politicians may try to influence and protect younger officers in an attempt to

gain their allegiance and support.

Furthermore, looking at their professional history, the number of transfers ( = -.359, p=.042) was

inversely associated with poor performance. The less the number of transfers a police officer went

through, the higher the chance that the police officer performed poorly. (Once again this reconfirms

the findings earlier that rotation plays a healthy role in staff development.) Due to the minimal

opportunity to be assigned to different situations, this group of police officers tended to maintain

routinary tasks and operate in their comfort zone, offering little opportunity for leadership growth.

4.c. Thematic Analysis

FGDs with the good performing and poor performing officers produced the following results,

which emphasized the combined importance of training and intrinsic leadership skills among

potential officers. The next section elaborates on the key findings.

Individual characteristics. Both strong performing and poor performing police officers described

the ideal police officer to be God-fearing, dependable, honest, self-disciplined and obedient, brave

and patriotic, considerate and patient, and loving. All agreed that there are still police officers who

possess these characteristics in the PNP. For them, innate characteristics intrinsic to the person

even before entering the workforce were critically important for these officials to perform at par

or even above standards. However, they emphasized that some characteristics, such as discipline

and accountability, can be addressed through more effective police training. Thus, the group

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 18

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

pointed out that new recruits, if not properly trained, are the ones prone to do unacceptable

behavior. Our discussions with police officers further highlighted the importance of attracting and

selecting the most competitive recruits, so that these individuals already had the strong building

blocks for leadership necessary to succeed as officers in the PNP.

On the other hand, both groups described a poor performing police officer to be hard-headed, tardy,

sensitive, jealous, discontented, materialistic, and arrogant. When asked why the poorly

performing officers behaved that way, they mentioned factors such as the environment they were

situated in, temptations within the organization, and their lack of material possessions.

Training. All new recruits of PNP undergo basic technical skills training. According to the officers

that participated in the FGD, they observed that the quality of training may potentially be

decreasing, signaled by the perceived lack of discipline and poorer performance of the new recruits

and younger officers. As evidence, they claimed that more than 32% of younger officers received

cases. Furthermore, they observed that new recruits are increasingly out of shape, which may be a

result of decreasing physical rigor of the current trainings. The officers highlighted that

maintaining physical fitness is crucial in performing their tasks, especially for operatives and field

officers. 6

However, officers mentioned that there are efforts to improve the training in the PNP. First, there

is a re-training program for poor performers. The officers who received grave cases and/or

suspended are required to go back to camp for 45 days for training. Second, more opportunities

for personal and leadership trainings are now being offered. An example of this is the My Brother’s

Keeper initiative that focuses on behavioral and spiritual development of the officers.

Subcultures. There are two main prevailing and opposite subcultures that the groups referenced:

“My Brother’s Keeper” (MBK from hereon) and Bata-Bata (Senior-Junior or BB from hereon)

systems. The MBK is a mentoring program that provides opportunities for young police officers

6 It is widely studied that increased in body mass index (BMI) is negatively associated to performance. Dawes et al.

(2018) found that overweight officers score lower in defense tactics compared to healthy counterparts. Another study

by Kukic et al. (2018) also found that increased BMI negatively affected police officers’ muscular endurance and

running performance. Apart from decreased physical performance, obese workers are more highly to get sick, acquire

disability, and thus, miss work (Arredondo, 2018).

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 19

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

(brother) to be adopted by senior police officers (keeper) in a bond of brotherhood and

accountability. The squad concept helps to ensure that each policeman in a unit will be accountable

to each other as they lookout for each other’s welfare. It involves support in terms of sharing advice

on career challenges, culture building, and spiritual guidance. This has been perceived to be a

positive influence on performance by the police participants.

On the other hand, the informal BB system breeds patronage between senior and junior officers.

The participants claimed that this system produced positive effects before such as sense of loyalty

and trust, but this has been abused over time, and used for personal gain, such as for protection

and promotion. They mentioned that if junior officers have senior officers backing them up, they

tend to be more complacent and arrogant. Opposite to MBK, the officers perceive this BB culture

to have negative effect on police performance.

Policies. As for policies within the police force that affected strong and poor performance, they

mentioned the support of top management specifically the President to their undertakings made

them change their mindset when it comes to service. Specifically, the internal cleansing policy

helped in making sure poor performing officers are culled out of their system, together with

sanctions for repeated misdemeanors. Through the internal cleansing policy, the PNP identifies a

list of officers with cases and provides intervention depending on their case. Interventions may be

punitive, such as dismissal or suspension; but recent changes in the PNP leadership have begun to

emphasize a more rehabilitative approach, tackling the root causes of poor performance (e.g. such

as commissioning this diagnostic study).

On the other hand, officers also mentioned that lack of policies that support police officers results

in potentially bad behavior. For example, according to them, they did not receive ample support

to perform their duties—and one example was the inadequate legal assistance when dealing with

court cases and appearances. At times, they were also compelled to use their own resources when

attending court hearings. By shouldering job-related expenses, some officers may be tempted to

engage in corrupt activities to make up for their out-of-pocket expenses. These types of informal

practices may have initially served as coping mechanisms. However, these probably also hardened

over time in order to become part of the organizational culture and common practice.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 20

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Public perception. Both groups claimed that negative public perception towards the police affects

morale and performance. According to their personal experiences, police officers are not regarded

highly and are treated disrespectfully by the public. This is especially intensified in highly

urbanized cities such as Metro Manila. While they implement maximum tolerance when dealing

with civilians, this persistent lack of respect may reduce the quality of their interpersonal relations

and interactions, such as losing patience and performing actions to exert their authority.

They acknowledged that media plays a critical role in shaping the public image of the PNP. For

instance, many of the news covering PNP feature issues of poor performing police officers, leading

to more negative perceptions and lack of trust towards the institution. There is desire from the

officers to work towards building public trust and creating better image for PNP. Through this,

they can gain confidence and prestige in performing their duties as a police officer and public

servant.

5. DISCUSSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The results highlight the effects of formal organizational culture, prevailing informal

organizational culture or “subcultures”, and personality traits on performance of police officers in

the Philippine National Police. The findings indicate that regardless whether the officer is strong

performing or poor performing, there is no difference in how they understand and perceive PNP’s

organizational culture in terms of its mission, adaptability, involvement and consistency. This

shows that PNP’s organizational culture is perceived as established, consistent and in some ways

quite rigid. The latter point has spurred informal coping mechanisms among many offices, some

of which have hardened over time to become common practice. Formal organizational culture is

not shown to predict whether officers will perform well or poorly. This suggests that instead of the

bigger, lofty ideals of the formal organizational culture, the “subcultures” or interactions among

officers and key stakeholders may play a bigger role in affecting performance and shaping officers’

development over time.

Indeed, “subcultures” in this context are seen to be formed as a way to respond to the rigidity and

convention of the formal organizational culture. Groups of officers in the organization tend to

adapt to the rigidities of the organization in order to accomplish their work while also working

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 21

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

around structures and rules not often seen as fair nor useful. “Subcultures” are molded by elements

of leadership, rituals, practices. and member composition prevailing in the group. These may then

create an environment which influences officers to either perform well or poorly.

On the individual level, the findings show that good performing officers are those who are more

self-confident, less open to external influences, and more likely to prefer working individually than

in teams. This can mean that officers with strong positive traits may less likely be influenced by

bad “subcultures”, and may instead contribute to good “subcultures”. Furthermore, good

performing officers are those who have undergone managerial skills training, highlighting that

more than operational skills, leadership is crucial in promoting good performance. The findings of

the focus group discussions emphasize the role of training, mentoring and leadership development

in strengthening good traits (e.g. discipline, honesty, reliability), and correcting bad ones (e.g.

tardiness, materialistic mindset, hard-headedness) at the individual level. To this, we add how

critically important it is to re-examine the selection and recruitment of officers given how the

building blocks of leadership characteristics may have already been honed prior to joining the

PNP.

Presented below is a general framework on how interventions can be structured.

FIGURE 1. Organizational Culture and Individual Personality in the Context of Subcultures

Source: Authors’ synthesis based on the literature and the main results of this study.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 22

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

The main findings of this study confirm with empirical evidence many expected areas for reform

engagement. We re-emphasize them here for future researchers to engage reformists in the PNP,

in an evidence-based change management agenda for the organization.

Revisit organizational culture to be more pragmatic and responsive

The formal organizational culture on paper appears sound; yet parts of it may be too rigid and may

have failed to adapt in pace with the challenges faced by the PNP and its officers. Some

components of the organizational culture need to be reviewed, and possibly reformed to be more

pragmatic and responsive to the current operations of the Philippine National Police. For instance,

misreporting (i.e. officers rotate the names declared on case filing) has become a way of operating

to address issues of workload and court appearances. And as noted earlier, coping mechanisms by

some officers may now include corrupt practices that help to augment the perceived effectiveness

of police operations. While perhaps initially well-meaning, these (and other) adaptive behaviors

can be addressed by focusing on the root issues of operational challenges faced by the organization.

Effective cascading of culture through change management

The good elements of the organizational culture, which includes the vision-mission, values and

beliefs, should, ideally, be cascaded down and throughout the organization. This can effectively

be done through adopting change management strategies. This starts with leaders understanding

the existing culture operating in the organization, and defining key reforms and aspirational target

culture. These are then incorporated in their communication, leadership alignment, and

organizational design, among others. Nevertheless, a purely top down approach here will likely

fail, as emphasized by the next point.

Strengthen subcultures through effective oversight on leadership and mentoring

The reality for the PNP is that it routinely engages with other stakeholders—such as local

government leaders and other stakeholders at the local level—that may, de facto, decentralize parts

of the operational influence and control over some of its units. Hence, in lieu of a top-down

organizational lens, better understanding and shaping subcultures become important areas for

intervention. This entails strengthening the good subcultures that cohere with the ideal

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 23

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

organizational culture, and at the same time, addressing the issues of the bad subcultures. For

example, MBK is identified as an innovation that created good subcultures. This may be reinforced

by finding ways to further institutionalize the said initiative. On the other hand, the organization

may look into reforming the BB system, which may have been initially useful, but now is regarded

in the context of bad subcultures. One simple yet powerful way to strengthen good subcultures

would be to formalize leadership and mentoring development as officers progress in their careers.

Effective techniques and outcomes can be identified and widely recognized by the organization,

with a view to further rooting these practices within the organization.

Strategic human resources

Human resource strategies could also be focused on enhancing the quality of recruitment and

training for younger officers. To start, there could be a more evidence-informed recruitment and

screening process for future officers. This study has confirmed a few traits that appear to be linked

to good performance--personality traits like openness, agreeableness and neuroticism, as well as

education level. The international literature attempting to predict good performance among police

officers further confirm additional traits worth monitoring for, including education, reading level

and age (which also proxies for maturity and experience in the workforce). 7

This may include a more deliberate analysis of the PNP recruitment process and data. It could also

involve a more formal collaboration not just with the Philippine National Police Academy but

other schools and criminology colleges as well, in order to examine and improve their programs,

ensuring individuals are better selected and trained even before they enter PNP. It is also crucial

to acknowledge that individuals may be self-selecting into the police force, so public perceptions

of what types of leaders are recruited by the PNP could make a big difference in the recruitment

pipeline. For instance, if young people perceive the PNP to be a corrupt organization, then the

7 White (2008) examined officers in a large metropolitan police department (anonymized) and found evidence that

reading level, age, gender and race were linked with better performance. Meanwhile, college education, military

experience and residency were not. In addition, Sanders (2003) observed that certain personality attributes were

consistently identified in the empirical literature as being linked to better performance—intelligence, common sense,

integrity, reliability and/or conscientiousness. Henson et al (2010) exposed issues in measurement of “good

performance”, yet also observed that measures of police academy performance and civil service exam score were

linked to job success for police officers in a Midwestern police department he examined during the period from 1996-

2006.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 24

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

better candidates may shun the organization, and instead those with the wrong motivations may be

more attracted to the PNP.

More generally, it is also crucial to develop a competency-based training, deployment and

promotion, so as to strengthen the culture of meritocracy in the organization. Ideally, the PNP

could establish very clear and evidence based processes that identify specific competencies and

skills for each promotion level in the organization. Not only could this could better inform the

training programs to be crafted by PNP; but it could also protect senior managers within the

organization from both internal and external influence on the promotions process.

Central dataset monitoring leadership development

Finally, a central dataset could enable the Philippine National Police to track performance of the

officers, and monitor the pipeline of its leaders. This will allow PNP to conduct periodic reviews

and make responsive, evidence-based decisions on their human resources. This study has

highlighted the routine diagnostics that such a system could produce. Through an empirical

analysis of the different success factors for performance over time, it would then be possible to

fine tune the organization’s policies guided and unified by evidence.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 25

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

REFERENCES

Aamodt, M., et al. 1997. “The Relationship between Education, Experience, and Police

Performance.” Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology: The Official Journal of the

Society for Police and Criminal Psychology, 12:2, 7. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/bf02806696.

Al-Ali, Omar E. 2011. Police Selection via Psychological Testing : A United Arab Emirates Study.

EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsble&AN=edsble.534494&scope=site

Arredondo, G.P. 2018. “Body mass index in a group of security forces (policemen). Cross-

sectional study.” New Insights Obes Gene Beyond, 2, 001-004.

Avolio, B., et al. 1990. “Age and Work Performance in Nonmanagerial Jobs: The Effects of

Experience and Occupational Type.” The Academy of Management Journal, 33:2,

407. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.256331&scope=site

Balch, R. 1972. “The Police Personality: Fact or Fiction?” The Journal of Criminal Law,

Criminology, and Police Science, 63:1, 106. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2307/1142281.

Barrick, M., et al. 1991. “The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Job Performance: A Meta-

Analysis.” Personnel Psychology, 44, 1-26.

Batalla, E. 2019. “Police corruption and its control in the Philippines.” Asian Education and

Development Studies, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print.

https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-05-2018-0099.

Cochrane, R., et al. 2003. “Psychological Testing and the Selection of Police Officers: A National

Survey.” Criminal Justice and Behavior, 4, 511. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edshol&AN=edshol.hein.journals.crmj

usbhv30.31&scope=site.

Crouter , A. C. 1984. “Spillover from Family to Work: The Neglected Side of the Work-Family

Interface.” Human Relations (New York, NY), 6, 425. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsfra&AN=edsfra.9080299&scope=si

te.

Dawes, J.J., Kornhauser, C.L., Crespo, D., Elder, C.L., indsay, K.G. and Holmes, R.J. 2018. “Does

Body Mass Index Influence the Physiological and Perceptual Demands Associated with

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 26

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Defensive Tactics Training in State Patrol Officers?” International Journal of Exercise

Science, 11:6, 319-330.

Denison, D., et al. 1995. “Towards a Theory of Organizational Culture and Effectiveness.”

Organization Science, 6:2, 204-223.

Frank, J. 2009. “Conceptual, methodological and policy considerations in the study of police

misconduct.” Criminology and Public Policy, 8:4,733-736.

Galliher, J. 1971. “Explanations of Police Behavior: A Critical Review and Analysis.” The

Sociological Quarterly, 12:3, 308. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.4105496&scope=site

Henson, B. et al. 2010. “Do good recruits make good cops? Problems predicting and measuring

academy and street-level success.” Police Quarterly, 13:1, 5-26.

Jiao, A. 2010. “Controlling corruption and misconduct: A comparative examination of police

practices in Hong Kong and New York.” Asian Criminology, 2010:5, 27-44.

Kane, R. and White, M. 2009. “Bad cops: A study of career ending misconduct among New York

City police officers.” Criminology and Public Policy, 8:4, 737-769.

Kreuzer, P. 2018. “Excessive Use of Deadly Force by Police in the Philippines Before Duterte.”

Journal of Contemporary Asia, 48:4, 671-684.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1471155.

Kubeck, Jean E., et al. 1996. “Does Job-Related Performance Decline with Age?” Psychology and

Aging, 1, 92. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao&AN=edsgcl.18488054&scope=

site.

Kukic, F., Cvorovic, A., Dawes, J., Orr, R.M. and Dopsaj, M. 2018. “Does BMI negatively impact

performance in local muscular endurance, sprint performance and metabolic power in

police.” Poster session presented at 2018 Rocky Mountain American College of Sports

Medicine Annual Meeting, Colorado Springs, United States.

McDaniel, M.A., Schmidt, F.L. and Hunter J.E. 1988. “Job experience correlates of performance”

Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 327-330.

Ng, T.W.H., and Feldman, D.C. Organizational Tenure and Job Performance. 2010. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsbas&AN=edsbas.CC287C20&scope

=site.

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 27

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Rhodes, S.R. 1983. “Age-related difference in work attidues and behavior: A review and

conceptual analysis” Psychological Bulletin, 93, 328-367.

Sanders, B. 2003. “Maybe there’s no such thing as a good cop: Organizational challenges in

selecting quality officers.” Policing: An international journal of police strategies and

management, 26:2, 313-328.

Schuck, A. M. 2014. “Gender Differences in Policing: Testing Hypotheses From the Performance

and Disruption Perspectives.” Feminist Criminology, 2, 160. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsbl&AN=RN350992120&scope=site.

Schmidt, F.L., Hunter, J.E. and Outerbridge, A.N. 1986. “Impact of job experience and ability on

job knowledge, work sample performance, and supervisory ratings of performance” Journal

of Applied Psychology, 71, 432-439.

Sinclair, A. 1993. “Approaches to Organisational Culture and Ethics.” Journal of Business Ethics,

1, 63. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgao&AN=edsgcl.13952078&scope=

site.

Stinson, P.M., et al. 2012. “Off duty and under arrest: A study of crimes perpetuated by off duty

police.” Criminal Justice Policy Review, 23:2,139-163.

White, M. 2008. “Identifying good cops early: Predicting recruit performance in the academy”

Police Quarterly, 11:1, 27-49.

Yutaka Ueda and Yoko Ohzono. 2013. “Differences in Work Values by Gender, Marital Status,

and Generation: An Analysis of Data Collected from ‘Working Persons Survey,

2010.’” International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 3:2. EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsnbk&AN=1474BE54F1D73F30&sc

ope=site.

+AMDG

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 28

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

APPENDIX

TABLE 1. Results of the Multiple Regression Analyses by Performance

Performance t p F df p adj. R2

Good Performance

Overall model for Personality Profile and Organizational Culture 2.28 9, 281 .018 .068

Openness -2.76 .006 -.199

Conscientiousness .16 .075 .158

Extraversion 1.17 .240 .091

Agreeableness -1.96 .051 -.145

Neuroticism -2.17 .031 -.155

Mission -.50 .619 -.046

Adaptability -.25 .807 -.020

Involvement .48 .630 .043

Consistency .02 .858 .018

Overall model for Professional History 15.85 2, 62 .000 .317

Years of Service .437 .663 .025

No. of transfers 9.46 .000 .535

Area of assignment -3.97 .000 -.228

Training on operational skills .908 .368 .094

Training on managerial skills 5.50 .000 .569

Overall model for Demographic Profile 4.58 7, 282 .000 .080

Age 4.03 .000 .269

Civil Status 1.36 .173 .087

Educational Attainment 2.00 .046 .115

Poor Performance

Overall model for Personality Profile and Organizational Culture .39 9, 174 .940 -.031

Openness .33 .744 .028

Conscientiousness -.46 .643 -.049

Extraversion -.67 .501 -.060

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 29

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

Agreeableness -.79 .433 -.068

Neuroticism -.26 .792 -.025

Mission -.07 .942 -.009

Adaptability .59 .559 .065

Involvement 1.01 .315 .116

Consistency -.51 .610 -.067

Overall model for Professional History 2.45 2, 34 .101 .075

No. of transfers -2.12 .042 -.359

Training on managerial skills 1.29 .205 .219

Overall model for Demographic Profile 5.301 2, 178 .006 .046

Age 1.96 .052 .143

Educational Attainment 2.25 .016 .177

Note: The significance level was tested at p<.05

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 30

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

ASOG WORKING PAPER 20-005 31

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3542046

You might also like

- PCPT JOHANA MIRAFLOR Personal Charter StatementDocument6 pagesPCPT JOHANA MIRAFLOR Personal Charter StatementPJr MilleteNo ratings yet

- Kay Kyle ToDocument13 pagesKay Kyle ToNell0% (1)

- Progress Report, Progress Report of LORITO Hug YCONGDocument2 pagesProgress Report, Progress Report of LORITO Hug YCONGnotsniwz@yahoo100% (1)

- Sustainable Development Plan: The PNPDocument36 pagesSustainable Development Plan: The PNPPJr MilleteNo ratings yet

- 44th Biennial Convention Program PDFDocument180 pages44th Biennial Convention Program PDFEnrique TrvjilloNo ratings yet

- Final Chapter 1 and 2 With Survey QuestionairesDocument22 pagesFinal Chapter 1 and 2 With Survey QuestionairesJEMAR MARIBONGNo ratings yet

- Survey Questionnaire (Eng)Document4 pagesSurvey Questionnaire (Eng)Hyman Jay BlancoNo ratings yet

- PNP shifts focus from Project Double Barrel to Project Double Barrel AlphaDocument2 pagesPNP shifts focus from Project Double Barrel to Project Double Barrel AlphaLynn N DavidNo ratings yet

- Initial Investigation ReportDocument2 pagesInitial Investigation ReportJosiah BacaniNo ratings yet

- St. Louis College of Bulanao: Title/Topic Technical English I Lesson 1 Introduction To Police Report WritingDocument7 pagesSt. Louis College of Bulanao: Title/Topic Technical English I Lesson 1 Introduction To Police Report WritingNovelyn LumboyNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Police: HistoryDocument6 pagesPhilippine National Police: HistorychenlyNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Arresting Officer: Prepared By: Acero, Mark Edrian R Ajero, Ryiji MariDocument16 pagesAffidavit of Arresting Officer: Prepared By: Acero, Mark Edrian R Ajero, Ryiji MariAllyssa Marie CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Calbayog Police Beat Patrol Checklist Report FormDocument7 pagesCalbayog Police Beat Patrol Checklist Report FormDaisy Jeanne Belarmino RosalesNo ratings yet

- Local Review of Related Literature in The Year 2017Document5 pagesLocal Review of Related Literature in The Year 2017Emmanuel James BasNo ratings yet

- Special Report re Burning Incident at DOLE STANFILCO PhilippinesDocument2 pagesSpecial Report re Burning Incident at DOLE STANFILCO PhilippinesTina Janio DoligolNo ratings yet

- Thesis TitleDocument4 pagesThesis TitleRegie BacalsoNo ratings yet

- Spot Report SampleDocument76 pagesSpot Report SampleErica JambonganaNo ratings yet

- Act Amending Articles 29, 94, 97, 98 and 99 of ACT No. 3815, As Amended, Otherwise Known As The Revised Penal CodeDocument71 pagesAct Amending Articles 29, 94, 97, 98 and 99 of ACT No. 3815, As Amended, Otherwise Known As The Revised Penal CodeClements YamiNo ratings yet

- Toaz - Info 2 Revised Thesis 1docx PRDocument54 pagesToaz - Info 2 Revised Thesis 1docx PRALDRIN QUINDOYOSNo ratings yet

- CDI-4 Technical English 2 (Legal Forms) : Daisyleen T. GamboaDocument15 pagesCDI-4 Technical English 2 (Legal Forms) : Daisyleen T. GamboaJessieNo ratings yet

- Introduction to PolygraphyDocument16 pagesIntroduction to PolygraphyCarla Jane TaguiamNo ratings yet

- Government Agencies Assigned to Control Drugs and Vices in the PhilippinesDocument19 pagesGovernment Agencies Assigned to Control Drugs and Vices in the PhilippinesKiven M. GeonzonNo ratings yet

- O'clockin The Morning A ShootingDocument3 pagesO'clockin The Morning A ShootingMark MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- Vices and Crimes DefinedDocument6 pagesVices and Crimes DefinedTuao Pnp PcrNo ratings yet

- Activity #15 (Lecture) Title of Activity: Legal Use of Ballistics Examination & Firearms ExaminationDocument11 pagesActivity #15 (Lecture) Title of Activity: Legal Use of Ballistics Examination & Firearms ExaminationJONES RHEY KIPAS100% (1)

- Memorandum: Oriental Mindoro Police Provincial OfficeDocument2 pagesMemorandum: Oriental Mindoro Police Provincial OfficeREYCYNo ratings yet

- Chin2 Case StudyDocument5 pagesChin2 Case StudyRonil ArbisNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Police National Capital Region Police Office Northern Police District Caloocan City Police StationDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Police National Capital Region Police Office Northern Police District Caloocan City Police StationRon LamsonNo ratings yet

- Front Page ThesisDocument46 pagesFront Page ThesisStephanie Torres Academia100% (1)

- Figure 1, Sample Form (Evidence Matrix) : Allegation Offence Elements/Facts in Issue Avenues of InquiryDocument7 pagesFigure 1, Sample Form (Evidence Matrix) : Allegation Offence Elements/Facts in Issue Avenues of InquiryKarsenley Cal-el Iddig Burigsay100% (1)

- PO2 Larry Ortega Dumandan JR CIC Class Number 308-2014: Investigative Report WritingDocument1 pagePO2 Larry Ortega Dumandan JR CIC Class Number 308-2014: Investigative Report WritingBrixter Dumalina AsanNo ratings yet

- Level of Satisfaction On The Effectiveness in PreservingDocument17 pagesLevel of Satisfaction On The Effectiveness in PreservingJamie BagundolNo ratings yet

- Murder Case Update at B. Mendoza StDocument7 pagesMurder Case Update at B. Mendoza StFaisal SultanNo ratings yet

- Police Rape and Murder CaseDocument4 pagesPolice Rape and Murder Caseangelica naquitaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court upholds conviction of brothers for illegal drug sale, possessionDocument98 pagesSupreme Court upholds conviction of brothers for illegal drug sale, possessionZsazsaRaval-TorresNo ratings yet

- Police Blotter Page No. 1 Nature of Incident: Stabbing TIME: On or About 9:50 PM DATE: January 15, 2021 Place of Occurrence: Barangay Person EnvolvedDocument2 pagesPolice Blotter Page No. 1 Nature of Incident: Stabbing TIME: On or About 9:50 PM DATE: January 15, 2021 Place of Occurrence: Barangay Person EnvolvedŘhëå Måë BåyLøń VërùtîåøNo ratings yet

- Comparative Police SystemsDocument14 pagesComparative Police SystemsMjay MedinaNo ratings yet

- Pendatun Avenue, Dadiangas East, General Santos CityDocument2 pagesPendatun Avenue, Dadiangas East, General Santos CityJulieto ResusNo ratings yet

- Unethical Issue Confronting PNP Police Brutality in The PhilippinesDocument21 pagesUnethical Issue Confronting PNP Police Brutality in The Philippinesnicollo atienzaNo ratings yet

- Stress Management Among Police Officers in Bislig City, PhilippinesDocument5 pagesStress Management Among Police Officers in Bislig City, PhilippinesIvylen Gupid Japos CabudbudNo ratings yet

- R e S T R I C T e DDocument8 pagesR e S T R I C T e Dgilbertmendova3No ratings yet

- QUEZON PPO ISO Accomplishment ReportDocument5 pagesQUEZON PPO ISO Accomplishment ReportArvin de AsisNo ratings yet

- Koronadal City Police StationDocument2 pagesKoronadal City Police StationJulieto ResusNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument9 pagesResearch PaperJess AvillaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Police Patrol on Compliance of Health ProtocolsDocument24 pagesEffectiveness of Police Patrol on Compliance of Health ProtocolsabigailNo ratings yet

- Local Media3801880649312132524Document44 pagesLocal Media3801880649312132524DarcknyPusodNo ratings yet

- Police ranks and equivalentsDocument1 pagePolice ranks and equivalentsJames Paulo AbandoNo ratings yet

- Quezon PPO OPLAN aims to strengthen anti-crime, drugs effortsDocument11 pagesQuezon PPO OPLAN aims to strengthen anti-crime, drugs effortsbitukoNo ratings yet

- Baguio Central University Criminology Internship in the Face of PandemicDocument37 pagesBaguio Central University Criminology Internship in the Face of PandemicFredix W. QuinioNo ratings yet

- PNP Booking Form 2Document1 pagePNP Booking Form 2Tsangngat ChaokasNo ratings yet

- Icct Colleges Foundation Inc. Cainta, RizalDocument1 pageIcct Colleges Foundation Inc. Cainta, RizalRomel A. De Guia100% (1)

- Special Report ReDocument2 pagesSpecial Report ReLevy DaceraNo ratings yet

- Comparative Police System JordanDocument4 pagesComparative Police System JordanJ Navarro100% (1)

- Effectiveness of The Mobile Patrol Unit (MPU) in Its Anti-Criminality Campaign in Bulusan, SorsogonDocument12 pagesEffectiveness of The Mobile Patrol Unit (MPU) in Its Anti-Criminality Campaign in Bulusan, SorsogonInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet