Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review Criteria For Research Manuscripts

Uploaded by

animesh pandaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Criteria For Research Manuscripts

Uploaded by

animesh pandaCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW CRITERIA FOR

RESEARCH MANUSCRIPTS

ACADEMIC MEDICINE, VOL. 76, NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 2001

I N T R O D U C T I O N

A Tool for Reviewers: ‘‘Review Criteria

for Research Manuscripts’’

Georges Bordage, MD, PhD, and Addeane S. Caelleigh

P

eer review lies at the core of science and academic ‘‘Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts’’ grew from an

life. In one of its most pervasive forms, peer review effort to address the need for more information about review

for the scientific literature is the main mechanism systems and reviewing in the medical education research

that research journals use to assess quality. Editors community. By forming a task force to concentrate on the

rely on their review systems to inform the choices they must needs of reviewers, we hoped to develop, sort, and present

make from among the many manuscripts competing for the information that would, in turn, help to increase the quality

few places available for published papers. In the past 50 of peer review that members of this community provide to

years, the use of peer review has become the ‘‘gold standard’’ journals and to one another. To meet this need, the task

by which journals are judged, just as journals use it to judge force focused on the core issues: Who needs information

papers. And whereas journals in all branches of science share most, and what information do they most need? The trajec-

the core ethos and values of peer review, it has evolved in tories of our answers to these questions (developed through

diverse ways to best fit the environments and circumstances a normative group process) crossed at reviewers and criteria,

of the various sciences and disciplines. and what we have produced is a reference tool for reviewers

However, our purpose in this task force report, ‘‘Review to use when they receive research manuscripts that they

Criteria for Research Manuscripts,’’ is not to discuss the gen- have been asked to review.

eral nature and permutations of peer review, as important as

those topics are. Others have already done this thoughtfully BACKGROUND

and well.1–4 Their work has focused on the tensions inherent

in the peer review process, the state of peer review and major When grappling with what information was needed and who

changes in it, particularly over the last 20 years, the devel- needed it, we could not ignore how perceptions of and at-

opment of data derived from research on peer review, and titudes toward peer review have changed over recent decades

specific areas of contention and ethics raised by the conduct and among different research communities. Further, these

of peer review. Our intention, in contrast, is to contribute changes have varied from discipline to discipline, field to

to the practice of review and develop a scholarly resource field, science to science. Peer review was originally con-

for reviewers to use as they review manuscripts. ceived to provide advice for the editor, the equivalent of

Both review and reviewers are often misunderstood by au- asking the knowledgeable colleague down the hall for an

thors and the reviewers themselves. Authors often feel that opinion. By the 1960s and 1970s, however, it had come to

decisions about their manuscripts are based on mysterious be the measure of quality for journals—high-quality journals

criteria and standards, in a largely secretive process run by use strong peer-review systems. When the National Library

editors and unknown reviewers. Their concerns about the of Medicine created Index Medicus in the 1960s, peer review

opacity of review processes are confirmed; Colaianni found was not a requirement for a journal’s inclusion, but it was a

that fewer than half of the journals in her sample of journals highly weighted factor, as remains the case today. As schol-

from four subject fields actually included clear statements arly publication flourished, particularly in the sciences, and

about their peer review practices.5 Reviewers, too, are hand- hundreds of new journals emerged, the expectation was that

cuffed by a lack of information; they are usually told little if these journals would be founded on the practice of peer re-

anything about their role in how decisions are made about view, and the practice was solidified.

journal articles or about what is expected of them.6 The spread of peer review and its adoption as the standard

904 ACADEMIC MEDICINE, VOL. 76, NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 2001

of quality brought with them, however, ethical and other The first, based in the social sciences, was Armstrong’s

problems that challenge the conduct normal in peer review 1982 article13 that reviewed research on science journals

systems. A few widely known cases of fraud and misconduct and the editorial policies of leading journals, and then pre-

(particularly the Darsee7 and Slutsky8 ones) that came to sented the implications and his recommendations for im-

light in the 1980s illustrated starkly the problems with au- provements. The second was Lock’s 1985 book,2 already

thorship, duplicate publication, and other publication mis- mentioned. The third, which is very recent, is the system-

conduct that many editors had been concerned and frus- atic review by Overbeke14; it is the best present summary

trated about for years. In 1978 the editors of ten source and introduction to studies in the area.

internationally prominent medical journals formed a group 䡲 Research into the kinds of reviewers who do better reviews

to begin cooperative work on common problems that af- for editors, that is, the types of reviews that editors value,

fected journals. Originally called the Vancouver Group (after has produced contradictory results so far. A 1993 study15

the site of their first meeting), the group soon took more found fairly strong evidence that good peer reviewers

formal shape and status, becoming the International Com- tended to be under age 40, were from top-ranked academic

mittee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The group has institutions, were well known to the editor, and were

become increasingly important over the past 20 years, meet- blinded to the identity of the paper’s author. A 1998

ing each year and periodically issuing consensus statements, study,16 on the other hand, was not able to identify the

which hundreds of other journals voluntarily sign on to. Sev- characteristics of good reviewers. The closest findings, very

eral of the statements deal indirectly, and some directly, with weak, were that reviewers between ages 40 and 60 did

peer review.9 better reviews than did those over age 60, and also that

In seeking to understand and improve peer review, editors reviewers educated in North America and trained in epi-

in biomedicine had more questions than answers, however. demiology or statistics did better reviews. These two stud-

Stephen Lock’s pivotal book, A Delicate Balance: Editorial ies were done at medical journals; there is not a parallel

Peer Review in Medicine,2 presented a systematic look at peer body of research for the social science journals.

review, bringing together the whole body of relevant re- 䡲 Studies in the biomedical sciences and social sciences over

search across the sciences. Then in 1989, the American the past decade produced mixed findings about using a

Medical Association sponsored the First International Con- masked review system, also called a double-blinded system.

gress on Peer Review in Biomedical Publication, and JAMA In a masked system, the reviewer does not know the iden-

published the proceedings in a special issue with the evoc- tity of the author or institution. This is in addition to the

ative title, ‘‘Guarding the Guardians: Research on Editorial customary practice of concealing the identity of the re-

Peer Review.’’ 10 Two other conferences followed, in Chicago viewer from the author. Studies in economics journals pro-

in 1993 and in Prague in 1997, each with a proceedings in duced strong support for using masked review.17–19 But sim-

JAMA,11,12 and a third conference is scheduled for Barcelona ilar studies of review in the bioscience journals have been

in September 2001. The emphasis of these meetings is re- more mixed, although evidence is firming on some issues.

search on peer review and other issues important in biosci- Although earlier research had indicated otherwise, two

ence journals; the importance of creating a community and randomized controlled trials in the 1990s found that mask-

forum for the presentation of research on peer review can ing made no difference in the quality of the reviews of

not be overstated. papers at prestigious biomedical journals.20,21 Likewise,

open peer review, where the identities of the author and

STATUS OF RESEARCH ON REVIEWING AND REVIEWERS reviewer are known to each other, apparently did not af-

fect the quality of reviews.22 Nonetheless, this issue is de-

The research by the bioscience editors is not the only re- bated strongly among editors, and more research is needed

search on peer review, although it has come to dominate in at the few journals that have open peer review.

the past decade. Parallel work has been done in psychology, 䡲 Reviewers have to respond to the widely varied expecta-

sociology, economics, and other fields. Taken together, this tions and procedures of the journals that ask them for re-

knowledge illuminates many aspects of review and provides views, because the journals have different ways of obtain-

increasing evidence that editors need to support their review ing information from them.6

systems or changes to them. In particular, two decades of 䡲 Journals have been able to develop validated assessment

research have deepened the understanding of reviewing and instruments to evaluate reviewers’ performances.22

reviewers. 䡲 Men and women may behave somewhat differently as re-

viewers. For example, a 1990 study reported that women

䡲 Three overviews at different times and from different per- reviewers accepted three times more articles by women

spectives have summarized what is known from research. authors than by men authors, where male reviewers ac-

ACADEMIC MEDICINE, VOL. 76, NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 2001 905

cepted equal proportions.23 And a 1994 study found dif- fresh their memories or unlearn bad habits. ‘‘Review Criteria

ferences between men and women in several review activ- for Research Manuscripts’’ was written to bring together a

ities.24,25 set of criteria for reviewing research manuscripts. If reviewers

䡲 Reviewers may react to papers differently, depending on feel uncomfortable—because they are new to reviewing, or

the content. Again, the findings are mixed. On the one because of concern that they are not doing reviewing well

hand, a study found that reviewers seemed to favor results —‘‘Review Criteria’’ can be a resource. Further, ‘‘Review

that support the status quo.26 In another study, reviewers Criteria for Research Manuscripts’’ orients the novice to how

did not react differently to content.25 journals work, the review process, and relevant ethical issues.

Regardless of the reviewer’s experience, training in review

Without doubt, the international congresses have focused benefits the journals and the scientific community. Just as

attention on peer review and dramatically increased the the ICMJE took shape in the 1980s to confront common

available research. Editors are working to understand their problems then, other groups began to form in the latter

systems better and to make evidence-based improvements to 1990s to deal with different as well as familiar issues. The

their peer review. World Association of Medical Editors was formed in 1995

to improve the quality of medical journals, particularly ones

WHAT IS NEEDED with limited resources and away from the centers of medical

publishing. It conducts its activities over the Internet and

Regrettably, the increase in research on peer review has not now has approximately 500 members internationally.

been accompanied by more teaching of peer review. Review- Among its early tasks was a statement of principles of pro-

ers receive very little preparation for performing reviews as fessionalism and responsibilities of editors, including prin-

part of their formal education. Nor do they receive it one- ciples for the review process and reviewers.28 The most re-

on-one from mentors, overworked attendings, dissertation cently formed is COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics),

supervisors, or lab chiefs. For, despite faculty’s and trainees’ which began in London in the spring of 1997 as a small

continuing belief that a mentor working one-on-one with a group of editors who met to discuss ethical problems the

student provides the best education, the reality is that few editors faced and must resolve, including those inherent in

trainees receive any help from faculty (mentors or otherwise) peer review.29

in such areas as reviewing, ethics, and writing for publica- It is also important to consider the effect that reducing

tion. Eastwood points out that ‘‘many such relationships reviewer bias would have not only on the careers of indi-

have deteriorated to the extent that faculty regard respon- vidual researchers but also on groups of researchers or their

sibilities such as peer review and the writing of book chapters fields of study, such as theories or methods of research. As

as independent opportunities for trainees’’ and that the sit- Beyer summarized the situation 25 years ago, even a small

uation has serious implications for the development of re- proportion of biased decisions would over time give some

viewers who are cognizant of the responsibilities of review.27 groups or individuals a large cumulative advantage. This is

New reviewers may be experts in particular fields, but each so because the bias would affect publication, which is used

one is at some time a complete novice as a reviewer. Most as the measure of merit upon which further promotion and

new reviewers have seen reviews because they have submit- advantage are based.30

ted their own papers to journals. Therefore, in a left-handed Some publications have dealt with the training of review-

way, they know about good reviews and bad reviews, but ers. Over the years, many editors have written short articles

from the author’s viewpoint. To review a paper for a journal in their journals offering advice about reviewing. These can

requires a different viewpoint, however. The reviewer is ex- be especially helpful because they offer both general guid-

pected to apply a set of outside criteria and standards to the ance and advice specific to particular research communities.

paper, to write constructive criticism for the author, to write The National Research Council of Canada, which publishes

a critique and make critical judgments that will aid the ed- 15 journals, developed a document (to our knowledge the

itor in making decisions, and to accept a set of ethical re- first) that summarized the responsibilities of authors, editors,

sponsibilities in relation to these activities. And unless this and reviewers.31 It remains an excellent resource but is little

newly invited reviewer is fortunate enough to have a helpful known. Most recently, Godlee and Jefferson’s book4 contains

mentor to turn to for guidance, these tasks must be under- instructional essays on reviewing, such as Moher and Jadad’s

taken without training or advice. ‘‘How to Peer Review a Manuscript,’’ 32 Altman and Schulz’s

‘‘Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts,’’ then, serves ‘‘Statistical Peer Review,’’ 33 and Demicheli and Hutton’s

two purposes and two audiences: to reaffirm the rules for ‘‘Peer Review of Economic Submissions.’’ 34 The first is

reviewing by developing criteria for reviewers who are early framed as tips that are ‘‘the result of our combined experi-

in their careers, and to help more experienced reviewers re- ence as peer reviewers for some 30 journals.’’ It is indeed a

906 ACADEMIC MEDICINE, VOL. 76, NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 2001

useful tool, and it summarizes relevant research well; how- circumstances, to set the standards to be used for different

ever, it focuses on generic aspects and has limited back- categories of papers, and perhaps these will differ at different

ground information. The others use lists of criteria, a format times in the journal’s development. Just as any assessment

much the same as the one in the ‘‘Review Criteria.’’ Because system must determine how good ‘‘good enough’’ must be,

statistics are an important part of analysis in many areas of journals must set the standards that will allow them not only

science, the Altman and Schultz lists have many of the same to separate the good papers from the poor ones, but also to

criteria as does the ‘‘Review Criteria.’’ (This is reassuring for choose which few good papers to publish from among many

all, since the task force derived its criteria lists independently good papers. This requires setting standards, and that is

through a normative group process before the Godlee and wholly the province of journals.

Jefferson book was available to them.) The Demicheli and

Hutton list also has overlaps with the ‘‘Review Criteria’’’s WHO CAN BENEFIT?

lists, although, as would be expected, it also has items spe-

cific to economics. ‘‘Review Criteria for Research Manuscripts’’ was written as

Researchers in some fields have used consensus confer- a reference tool for a wide community of reviewers. Because

ences to develop specific guidelines for reporting particular Academic Medicine and GEA—RIME are from the health

types of research. An example is the CONSORT (consoli- professions, and more specifically the branch for medical ed-

dated standards of reporting trials) statement and its 21-item ucation research, the resulting document is set in the re-

list and flow chart for presenting the fundamental informa- search framework most common to its members. More often

tion necessary to accurately evaluate the internal and exter- than not, the examples given come from the social and be-

nal validity of a randomized controlled trial.35,36 Two other havioral sciences that are the framework of the majority of

examples are known. The 1999 QUOROM (Quality of Re- their research. ‘‘Review Criteria’’ has cast its criteria in the

porting of Meta-analyses) statement is similar to the CON- most general, widely applicable form precisely so that they

SORT in that it has a statement, itemized list, and flow can be used by researchers working in the widest possible

chart,37 and in 2000 a consensus group issued the MOOSE range of sciences and disciplines. We think they apply in

checklist, summarizing recommendations for reporting meta- areas beyond the social and behavioral sciences, perhaps in

analyses of observational studies in epidemiology.38 some areas of the biosciences and physical sciences. The

The task force that prepared this document dealt with greater the distance from these sciences, however, the more

reviewing rather than reporting, and it chose to present the the users may need to adapt parts of the criteria or add to

core of its recommendations as criteria. Because reviewing is them in order to make them work well for the research and

about assessing and making judgments, reviewers are apply- traditions of their own fields.

ing different criteria and standards at different times and By extension, researchers can also use ‘‘Review Criteria

places. In formal protocols or by informal consensus, a re- for Research Manuscripts’’ to plan and conduct their studies

search community can agree upon the standards for research and to write papers properly prepared to compete for publi-

in a particular field. But often there is no consensus. And cation in peer-reviewed journals and to truly contribute to

in some fields, especially cross-disciplinary or newly emerging the scientific literature. By a further extension, the docu-

ones, there may be no agreement as to the criteria, let alone ment can be used as a resource for faculty development to

the standards, to be applied. train authors and reviewers. Finally, editors may find it use-

The existence of the task force and these review criteria ful, perhaps to help in creating or revising review forms or

are a statement that there are basic criteria for research re- in working with other editors.

ports that cut across disciplines and fields. Through the re- No matter how important they may be, however, all these

view criteria, the task force has taken the position that good additional groups are secondary to the original audience—

review is about making careful, systematic judgments, about reviewers. The Task Force wrote ‘‘Review Criteria for Re-

assessing strengths and pointing out weaknesses, and about search Manuscripts’’ for them.

making global assessments if requested by the editor. We

want to be clear about an important point, however: laying

out these criteria is entirely separate from setting the stan- REFERENCES

dards to be used in making decisions about which papers a 1. Freese L. On changing some role relationships in the editorial review

journal will publish. The criteria are the elements that re- process. Am Sociologist. 1979;14(Nov):231–8.

viewers should consider in preparing a review. And reviewers 2. Lock S. A Difficult Balance: Editorial Peer Review in Medicine. Phil-

adelphia, PA: ISI Press, 1985.

will apply their own professional standards as they use the 3. Chubin DE, Hackett EJ. Peer review and the printed word. In: Peerless

criteria to prepare a review for the editor. But it is the duty Science: Peer Review and U.S. Science Policy. Albany, NY: State Uni-

of the journal, based on the journal’s mission, traditions, and versity of New York Press, 1990.

ACADEMIC MEDICINE, VOL. 76, NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 2001 907

4. Godlee F, Jefferson T (eds). Peer Review in Health Sciences. London, uating peer reviews: pilot testing of a grading instrument. JAMA. 1994;

U.K.: BMJ Books, 1999. 272:117–9.

5. Colaianni LA. Peer review in journals indexed in Index Medicus. 23. Lloyd ME. Gender factors in reviewer recommendations for manuscript

JAMA. 1994;272:156–8. publication. J Appl Behav Anal. 1990;23:539–43.

6. Frank E. Editors’ requests of peer reviewers: a study and a proposal. 24. Gilbert JR, Williams ES, Lundberg GD. Is there gender bias in JAMA’s

Prevent Med. 1996;25:102–4. peer review process? JAMA. 1994;272:139–42.

7. Stewart WW, Feder N. The integrity of the scientific literature. Nature. 25. Caelleigh AS, Hojat M, Steinecke A, Gonnella JS. Effects of reviewers’

1987;325:207–14. gender on assessments of a gender-related standardized manuscript,

8. Locke R. Another damned by publications. Nature. 1986;324:401. 2001 [unpublished].

9. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform Require- 26. Mahoney MJ. Publication prejudices: an experimental study of confirm-

ments for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals [and Separate atory bias in the peer review system. Cogn Ther Res. 1977;1:161–75.

Statements]. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:36–47; 具www.acponline.org/ 27. Eastwood S. Ethical issues in biomedical publication. In: Jones AH,

journals/annals/01janr97/unifreq典 (updated May 1999). McLellan F (eds). Ethical Issues in Biomedical Publication. Baltimore,

10. Guarding the guardians: research on editorial peer review. JAMA. MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000:251.

1990;263:1309–456. 28. World Association of Medical Editors. 具www.wame.org典. Accessed 6/1/

11. The Second International Congress on Peer Review in Biomedical Pub- 01.

lication. JAMA. 1994;272:79–174. 29. Guidelines on Good Publication Practice. The COPE Report 1999.

12. The Third Congress on Biomedical Peer Review. JAMA. 1998;280: 具www.bmjpg.com/publicationethics/cope/cope1999典. Accessed 6/1/01.

203–306. 30. Beyer JM. Editorial policies and practices among leading journals in

13. Armstrong JS. Research on scientific journals: implications for editors four scientific fields. Sociol Q. 1978;19:68–88.

and authors. J Forecasting. 1982;1:83–104. 31. National Research Press. Part 4: Responsibilities. In: Publication

Policy 具http://www.monographs.nrc.ca/cgi㛭bin/cisti/journals/rp/rpz㛭cust

14. Overbeke J. The state of evidence: what we known and what we don’t

㛭e?pubpolicy典. Accessed 6/5/01.

know about journal peer review. In: Godlee F, Jefferson T (eds). Peer

32. Moher D, Jadad AR. How to peer review a manuscript. In: Godlee F,

Review in the Health Sciences. London, U.K.: BMJ Press, 1999:32–

Jefferson T. (eds). Peer Review in Health Sciences. London, U.K.: BMJ

44.

Books, 1999.

15. Evans AT, McNutt RA, Fletcher SW, Fletcher RH. The characteristics

33. Altman DG, Schulz KF. Statistical peer review. In: Godlee F, Jefferson

of peer reviewers who produce good-quality reviews. J Gen Intern Med.

T (eds). Peer Review in Health Sciences. London, U.K.: BMJ Books,

1993;8:422–8.

1999.

16. Black N, Van Rooyen, Godlee F, Smith R, Evans S. What makes a

34. Demicheli V, Hutton J. Peer review of economical submissions. In:

good reviewer and a good review for a general medical journal? JAMA.

Godlee F, Jefferson T (eds). Peer Review in Health Sciences. London,

1998;280:231–3. U.K.: BMJ Books, 1999.

17. Blank RM. The effects of double-blind versus single-blind reviewing: 35. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting

experimental evidence from The American Economic Review. Am Econ of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. JAMA.

Rev. 1991;81:1041–67. 1996;276:637–9.

18. Lebrand DN, Piette MJ. Does the blindness of peer review influence 36. Rennie D. CONSORT revised—improving the reporting of random-

manuscript selection efficiency? Southern Econ J. 1994;60:896–906. ized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:2006–7.

19. Lebrand DN, Piette MJ. A citation analysis of the impact of blinded 37. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational

peer review. JAMA. 1994;272:147–9. studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Ob-

20. Van Rooyen S, Godlee F, Evans S, et al. Effect of blinding and un- servational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;

masking on the quality of peer review. JAMA. 1998;280:240–2. 283:2008–12.

21. Justice AC, Cho MK, Winker MA, Berlin JA, Rennie D, PEER inves- 38. Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports

tigators. Does masking author identity improve peer review quality? a of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM state-

randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:240–2. ment. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354(1993):

22. Fruer ID, Becker GJ, Picus D, Ramirez E, Darcy MD, Hicks ME. Eval- 1896–900.

908 ACADEMIC MEDICINE, VOL. 76, NO. 9 / SEPTEMBER 2001

You might also like

- An Introduction to Bibliometrics: New Development and TrendsFrom EverandAn Introduction to Bibliometrics: New Development and TrendsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Measuring Academic Research: How to Undertake a Bibliometric StudyFrom EverandMeasuring Academic Research: How to Undertake a Bibliometric StudyNo ratings yet

- Ejifcc 25 227Document17 pagesEjifcc 25 227api-395804642No ratings yet

- MIS696A 2011 On Peer Review Standards For The Information Systems LiteratureDocument15 pagesMIS696A 2011 On Peer Review Standards For The Information Systems LiteratureCássio Batista MarconNo ratings yet

- The Seven Deadly Sins of Communication ResearchDocument23 pagesThe Seven Deadly Sins of Communication ResearchfabregaalfonsoNo ratings yet

- Criterios de Evaluacion para La Inv. Cualitativa en Cuidado de SaludDocument9 pagesCriterios de Evaluacion para La Inv. Cualitativa en Cuidado de SaludeacoboNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature in Case StudyDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature in Case Studybeqfkirif100% (1)

- Review of ReviewDocument11 pagesReview of ReviewAvril CastañoNo ratings yet

- What Literature Review in ResearchDocument4 pagesWhat Literature Review in Researchc5ngamsd100% (1)

- Bornmann 2008Document18 pagesBornmann 2008veromachadoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Review Related LiteratureDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Review Related Literaturedhjiiorif100% (1)

- Peer Review System A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesPeer Review System A Systematic ReviewNabil GhifarieNo ratings yet

- What Is A Literature Review in Research PaperDocument7 pagesWhat Is A Literature Review in Research Paperyelbsyvkg100% (1)

- Writing Literature Review of Research PaperDocument7 pagesWriting Literature Review of Research Papergw32pesz100% (1)

- Reading Qualitative Studies Margarete Sandelowski and Julie BarrosoDocument47 pagesReading Qualitative Studies Margarete Sandelowski and Julie BarrosoColor SanNo ratings yet

- Is A Literature Review Qualitative or Quantitative ResearchDocument5 pagesIs A Literature Review Qualitative or Quantitative ResearchafmzsgbmgwtfohNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On IjarahDocument10 pagesLiterature Review On Ijarahafmzvadopepwrb100% (1)

- Sense About Science: "I Don'T Know What To BELIEVE... "Document8 pagesSense About Science: "I Don'T Know What To BELIEVE... "65daysofsteveNo ratings yet

- Writing Narrative Literature ReviewsDocument17 pagesWriting Narrative Literature ReviewsMatthew LloydNo ratings yet

- Cit Analysis Ss.2021Document4 pagesCit Analysis Ss.2021HenrickNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Systematic and Narrative Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesDifference Between Systematic and Narrative Literature ReviewafdtfhtutNo ratings yet

- Writing Narrative Literature Reviews For Peer-Reviewed Journals: Secrets of The TradeDocument17 pagesWriting Narrative Literature Reviews For Peer-Reviewed Journals: Secrets of The TradeDr. Naji ArandiNo ratings yet

- Why Literature Review Is Important in A ResearchDocument7 pagesWhy Literature Review Is Important in A Researchojfhsiukg100% (1)

- Literature Review Fundamental Analysis PDFDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Fundamental Analysis PDFafmzvaeeowzqyv100% (1)

- Four Main Sources of Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesFour Main Sources of Literature Reviewea30d6xs100% (1)

- Systematic Literature Reviews An IntroductionDocument10 pagesSystematic Literature Reviews An IntroductiondeepikaNo ratings yet

- Example of Scientific Literature Review PaperDocument4 pagesExample of Scientific Literature Review Paperafmzubsbdcfffg100% (1)

- How To Write A Systematic Review Article and MetaDocument18 pagesHow To Write A Systematic Review Article and MetaAyman Al HasaarNo ratings yet

- Joc 11740Document4 pagesJoc 11740Sebastian RamosNo ratings yet

- PEER REVIEW: Open ReviewDocument4 pagesPEER REVIEW: Open ReviewMichaelaPomPomNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal Systematic Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesCritical Appraisal Systematic Literature Reviewhyz0tiwezif3100% (1)

- Medical PublishingDocument6 pagesMedical PublishingRilla FiftinaNo ratings yet

- What Is Review of Related Studies in ThesisDocument8 pagesWhat Is Review of Related Studies in ThesisWendy Belieu100% (2)

- Primary and Secondary Sources in Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesPrimary and Secondary Sources in Literature Reviewc5rk24grNo ratings yet

- Review of LiteratureDocument11 pagesReview of Literaturelakhvindersingh650% (1)

- Jabar, Farhan Scientific - Research - PublicationDocument8 pagesJabar, Farhan Scientific - Research - PublicationMOHD FARHAN BIN ABD JABAR MKM213026No ratings yet

- Literature Review Strengths and LimitationsDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Strengths and Limitationsafdtvdcwf100% (1)

- Authorship of Research PapersDocument14 pagesAuthorship of Research PapersDarlington EtajeNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Vs BackgroundDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Vs Backgroundaflsmperk100% (1)

- What Is A Peer Reviewed Literature Review PaperDocument7 pagesWhat Is A Peer Reviewed Literature Review Paperea4c954q100% (1)

- A Citation Analysis of The Philippine Journal of Nutrition, 2001-2011 PDFDocument19 pagesA Citation Analysis of The Philippine Journal of Nutrition, 2001-2011 PDFrefreshNo ratings yet

- Format of Literature Review ExampleDocument6 pagesFormat of Literature Review Examplec5pgcqzv100% (1)

- How To Write A Research Paper Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesHow To Write A Research Paper Literature Reviewea84e0rr100% (1)

- A Typology of Reviews - An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated MethodologiesDocument19 pagesA Typology of Reviews - An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologiesdari0004No ratings yet

- APA Style Guide For Publishing ArticlesDocument19 pagesAPA Style Guide For Publishing Articlesyounis.faridNo ratings yet

- Maria Grant, Types of Reviews.Document18 pagesMaria Grant, Types of Reviews.StefiSundaranNo ratings yet

- Samples of Literature Review in Research PaperDocument6 pagesSamples of Literature Review in Research Paperaflsmawld100% (1)

- Literature Review Method PDFDocument9 pagesLiterature Review Method PDFc5rc7ppr100% (1)

- Assignments Samples CritiqueDocument31 pagesAssignments Samples CritiqueNadzirah RozaimiNo ratings yet

- What Is The Point of A Literature Review in A Research PaperDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Point of A Literature Review in A Research PaperafmzhfbyasyofdNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Research SampleDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Research Samplec5s8r1zc100% (1)

- I Publish in I Edit? - Do Editorial Board Members of Urologic Journals Preferentially Publish Their Own Scientific Work?Document5 pagesI Publish in I Edit? - Do Editorial Board Members of Urologic Journals Preferentially Publish Their Own Scientific Work?hsayNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Research Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesQuantitative Research Literature Reviewafdtbflry100% (1)

- Conclusion Literature Review ExampleDocument8 pagesConclusion Literature Review Examplec5qrve03100% (1)

- 2004, Gephart, Qualitative Research and The Academy of Management JournalDocument10 pages2004, Gephart, Qualitative Research and The Academy of Management JournalSerge LengaNo ratings yet

- Article Review SampleDocument7 pagesArticle Review SampleMatin Ahmad Khan90% (10)

- Literature Review For A Research PaperDocument4 pagesLiterature Review For A Research Paperaflsmyebk100% (1)

- What Is Review of Related Literature in A Research PaperDocument4 pagesWhat Is Review of Related Literature in A Research Paperpimywinihyj3No ratings yet

- RCT Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesRCT Literature Reviewea7e9pm9100% (1)

- How Professors Think: Inside the Curious World of Academic JudgmentFrom EverandHow Professors Think: Inside the Curious World of Academic JudgmentRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- Brain DeathDocument43 pagesBrain Deathanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Cardiogenic ShockDocument20 pagesCardiogenic Shockanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Cardio Pulmonary ResuscitationDocument34 pagesCardio Pulmonary Resuscitationanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Acute Kidney FailureDocument8 pagesAcute Kidney Failureanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- DVTDocument6 pagesDVTAnusikta PandaNo ratings yet

- Bladder TraumaDocument5 pagesBladder Traumaanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- StatisticsDocument77 pagesStatisticsanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- ThalassemiaDocument24 pagesThalassemiaanimesh panda100% (1)

- Artificial Cardiac PacemakersDocument25 pagesArtificial Cardiac Pacemakersanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- 2 Pain ManagementDocument32 pages2 Pain Managementanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Snake Bite Management MICRODocument5 pagesSnake Bite Management MICROanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- LESSOON PLAN Infection PreventionDocument9 pagesLESSOON PLAN Infection Preventionanimesh panda100% (1)

- PoisoningDocument52 pagesPoisoninganimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- How To Write ManuscriptDocument9 pagesHow To Write Manuscriptanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On CPRDocument3 pagesLesson Plan On CPRanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Measures of DispersionDocument9 pagesMeasures of Dispersionanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- 05 Lecture4 - EstimationDocument37 pages05 Lecture4 - EstimationLakshmi Priya BNo ratings yet

- Iv CannulationDocument5 pagesIv Cannulationanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- SPECIFIC OBJECTIVE: On Completion of The Class StudentsDocument15 pagesSPECIFIC OBJECTIVE: On Completion of The Class Studentsanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Charateristics of A Good RecordDocument2 pagesCharateristics of A Good Recordanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On BLSDocument3 pagesLesson Plan On BLSanimesh panda100% (1)

- LESSON PLAN ON Hand WashingDocument3 pagesLESSON PLAN ON Hand Washinganimesh panda50% (2)

- Lesson Plan On EcgDocument3 pagesLesson Plan On Ecganimesh panda100% (1)

- Standard Deviation CalculationDocument3 pagesStandard Deviation Calculationanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument6 pagesINTRODUCTIONanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument4 pagesINTRODUCTIONanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Tests of IntelligenceDocument6 pagesTests of Intelligenceanimesh panda100% (1)

- Tracheostomy Tube SizesDocument1 pageTracheostomy Tube Sizesanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- The Test Publisher Includes Suggested Score ClassiDocument1 pageThe Test Publisher Includes Suggested Score Classianimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- SGRJ V29 28-35 Campbell 12-14Document8 pagesSGRJ V29 28-35 Campbell 12-14citraNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Log Week 2Document7 pagesDaily Lesson Log Week 2Jolie Ann De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Soal News ItemDocument11 pagesSoal News ItemYehezkiel Rivaldo Widjaya100% (1)

- TVL Bread & Pastry Production-Q1-M4Document14 pagesTVL Bread & Pastry Production-Q1-M4John Paul AnapiNo ratings yet

- Title: Anthrax: Subtitles Are FollowingDocument14 pagesTitle: Anthrax: Subtitles Are FollowingSyed ShahZaib ShahNo ratings yet

- STA60104 TutorialsDocument123 pagesSTA60104 TutorialsSabrina NgoNo ratings yet

- User Manual: Model 4779 Tru-Trac® Traction UnitDocument46 pagesUser Manual: Model 4779 Tru-Trac® Traction UnitSejmet IngenieriaNo ratings yet

- RUBRIC Tracheostomy Care and SuctioningDocument4 pagesRUBRIC Tracheostomy Care and SuctioningElaine Marie SemillanoNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 Module 4 Q1Document4 pagesPractical Research 2 Module 4 Q1Black CombatNo ratings yet

- 2 Do Rooms and An - ADocument18 pages2 Do Rooms and An - ASelena MayorgaNo ratings yet

- CBT Case Study PresentationDocument12 pagesCBT Case Study Presentationstefiano100% (1)

- Literature Review: Terapi Relaksasi Otot Progresif Terhadap Penurunan Tekanan Darah Pada Pasien HipertensiDocument8 pagesLiterature Review: Terapi Relaksasi Otot Progresif Terhadap Penurunan Tekanan Darah Pada Pasien Hipertensinadia hanifaNo ratings yet

- Manahaw Elementary School Child Protection PolicyDocument3 pagesManahaw Elementary School Child Protection PolicyRenelyn Rodrigo SugarolNo ratings yet

- Isbar WorksheetsDocument2 pagesIsbar Worksheetsapi-688564858No ratings yet

- Alan Petersen - Emotions Online - Feelings and Affordances of Digital Media-Routledge (2022)Document192 pagesAlan Petersen - Emotions Online - Feelings and Affordances of Digital Media-Routledge (2022)jsprados2618No ratings yet

- Journal of Adolescent Health J HoltgeDocument9 pagesJournal of Adolescent Health J HoltgeAdina IgnatNo ratings yet

- Loads of Continuous Mechanics For Uprighting The Second Molar On The Second Molar and PremolarDocument8 pagesLoads of Continuous Mechanics For Uprighting The Second Molar On The Second Molar and PremolarAlvaro ChacónNo ratings yet

- Izombie Rules (D20 Modern Variant Rule) : Zombie StatsDocument7 pagesIzombie Rules (D20 Modern Variant Rule) : Zombie StatsJames LewisNo ratings yet

- FNCPDocument11 pagesFNCPCATHRYN MAE GAYLANNo ratings yet

- Inserting A Foley Catheter On A Male Patient: Lecturer: Compiled By: Group 7Document7 pagesInserting A Foley Catheter On A Male Patient: Lecturer: Compiled By: Group 7ratih kusuma dewiNo ratings yet

- LNG-502 NotesDocument13 pagesLNG-502 NotesAyesha RathoreNo ratings yet

- Nursing SeatmatrixDocument8 pagesNursing SeatmatrixKanza KaleemNo ratings yet

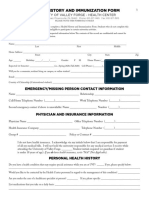

- Health History and Immunization Form: University of Valley Forge - Health CenterDocument4 pagesHealth History and Immunization Form: University of Valley Forge - Health CenterBernard AmetepeNo ratings yet

- F3 Exam PaperDocument20 pagesF3 Exam PaperAgnes Hui En WongNo ratings yet

- Apr W1,2Document6 pagesApr W1,2Toànn ThiệnnNo ratings yet

- Fourth Quarter Reviewer in Mapeh 7 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS: Review The Following Questions. The Answer Keys Are Indicated in The LastDocument5 pagesFourth Quarter Reviewer in Mapeh 7 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS: Review The Following Questions. The Answer Keys Are Indicated in The LastUnibelle Joy LachicaNo ratings yet

- FEM 3202-3 LipidDocument15 pagesFEM 3202-3 LipidRon ChongNo ratings yet

- Research Journal The Pendulum 2018 CompressedDocument144 pagesResearch Journal The Pendulum 2018 Compressedgladys damNo ratings yet

- TETRINDocument2 pagesTETRINDr.2020No ratings yet

- Module 1: Health AssessmentDocument16 pagesModule 1: Health AssessmentAmberNo ratings yet