Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 203.198.184.26 On Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

Uploaded by

(Janvier) NG Xi Yi Janvier CaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 203.198.184.26 On Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

Uploaded by

(Janvier) NG Xi Yi Janvier CaCopyright:

Available Formats

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

Author(s): Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

Source: The Future of Children , Fall 2016, Vol. 26, No. 2, Starting Early: Education

from Pre Kindergarten to Third Grade (Fall 2016), pp. 159-183

Published by: Princeton University

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43940586

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Future of Children

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the

United States

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

Summary

Simply put, children with poor English skills are less likely to succeed in school and beyond.

What s the best way to teach English to young children who aren't native English speakers?

In this article, Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers examine the state of English learner

education in the United States and review the evidence behind different teaching methods.

Models for teaching English learner children are often characterized as either English

immersion (instruction only in English) or bilingual education (instruction occurs both in

English and in the students' native language), although each type includes several broad

categories. Which form of instruction is most effective is a challenging question to answer,

even with the most rigorous research strategies. This uncertainty stems in part from the

fact that, in a debate with political overtones, researchers and policymakers don't share a

consensus on the ultimate goal of education for English learners. Is it to help English learner

students become truly bilingual or to help them become proficient in the English language as

quickly as possible?

On the whole, Barrow and Markman-Pithers write, its still hard to reach firm conclusions

regarding the overall effectiveness of different forms of instruction for English learners.

Although some evidence tilts toward bilingual education, recent experiments suggest that

English learners achieve about the same English proficiency whether they're placed in

bilingual or English immersion programs. But beyond learning English, bilingual programs

may confer other advantages - for example, students in bilingual classes do better in their

native languages. And because low-quality classroom instruction is associated with poorer

outcomes no matter which method of instruction is used, the authors say that in many

contexts, improving classroom quality may be the best way to help young English learners

succeed.

www.futureofchildren.org

Usa Barrow is a senior economist and research advisor in the economic research department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Lisa Markman-Pithers is the associate director of the Education Research Section at Princeton University, the outreach director for

Future of Children, and a lecturer at Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

The authors thank Cecilia Rouse, Ellen Frede, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Lauren Sartain for helpful comments and discussions and Ross

Cole for excellent research assistance.

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 159

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

possible? The debate is politically charged,

advantages. At the most and tolerance of or support for bilingual

basic level, speaking two education has varied over time.3

or more languages creates

Being basic advantages. or more more bilingualmore

level, economic laneconomic

guages speaking At brings the aand

nd most creatsocial

es social two many The State of US English Learner

Education

opportunities as it expands the number of

people you can communicate with in an

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

increasingly global economy And some

the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of

research indicates that bilingual people

1974 require public schools to help English

have higher levels of executive functioning,

learner students "participate meaningfully

particularly when it comes to inhibitory

and equally in educational programs."4

control and cognitive flexibility.1 These skills

have been found to correlate with academic School districts must identify potential

English learner students, assess English

success. (See the article in this issue by

language proficiency on an annual basis, and

Cybele Raver and Clancy Blair for a full

continue to monitor former English learner

description of executive function and its

relation to school success.) Some evidence students for at least two years after English

proficiency is established. With the passage of

even suggests that bilingualism may protect

the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Title

against the cognitive decline associated with

III established federal formula grants for

aging.2 Although there is near consensus that

states to support the needs of English learner

bilingualism is beneficial, bilingual education

students aged 3-21, with the goal of helping

itself is a complex and controversial topic.

them attain English language proficiency.

One aspect of US bilingual education is

Much of the policy, including these grants,

teaching languages other than English to

was retained in the reauthorization under the

students whose first language is English. In

this article, we focus on another aspect - Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015.

teaching English to children who aren't No Child Left Behind specifically refers to

native English speakers. children who are limited English proficient

(LEP), while the ESSA replaced the term

For decades, researchers, educators, and with English learners. We use English

policymakers have debated how best to learners throughout this article.

prepare young children whose native

language isn't English to succeed in In defining English learners, ESSA and the

classrooms where English is the language Improving Head Start for School Readiness

of instruction, with very little conclusive Act of 2007 (HS A) refer to "difficulties in

evidence. The crux of the debate surrounds speaking, reading, writing, or understanding

the amount, frequency, and duration with the English language, that may be sufficient

which students should use their native to deny the individual a) the ability to meet

language in school, which is in large part the challenging State academic standards;

associated with the underlying educational b) the ability to successfully achieve in

goal: Is the intent to make students bilingual classrooms where the language of instruction

(fluent in both their native language and is English; or c) the opportunity to participate

English), or is it to make sure that English fully in society."5 ESSA also holds states

learners master the language as rapidly as accountable by requiring them to adopt

160 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

English language proficiency standards that programs have no policies regulating services

"(i) are derived from the four recognized for English learners; 24 states permit

domains of speaking, listening, reading, programs to offer bilingual preschool classes;

and writing; (ii) address the different and 14 states permit monolingual, non-

proficiency levels of English learners; and English preschool classes.8 As a result, we see

(iii) are aligned with the challenging State a wide variety of programs across the United

academic standards." The act also requires States at both the preschool and primary

local education agencies that receive grade levels.

Title III funds to "demonstrate success in

increasing - (A) English language proficiency; In table 1, we present data on the proportion

and (B) student academic achievement." of children who speak a language other

Similarly, HS A performance standards than English in the home, as well as the

include language about ensuring that English proportion identified as English learners

learner children are making progress toward or LEP. In 2014, more than one-fifth

English language acquisition.6 Based on these of US children aged 5-9 were potential

policies, education of English learners in the English learners, meaning that they spoke a

United States by and large means programs language other than English in their home.

designed to help these students achieve For children under 5 years of age, we have

proficiency in English. National policy isn't less comprehensive data; we report figures

focused on teaching students to be proficient from Head Start programs, which primarily

in more than one language. That said, ESSA serve three- and four-year-olds, and from

requires only that programs for developing select states for which data on preschool-

English proficiency be "evidence-based," aged children are available. The proportion

not that the program be designed to make of Head Start students who report a home

students fluent only in English or bilingual language other than English fell slightly

in English and their native language. The between 2004 and 2014, from 29 to 28

HSA is similarly noncommittal about percent, while the proportion of five- to

which programs Head Start Centers are nine-year-olds reporting a home language

to implement. But the Head Start Early other than English rose from 19 percent in

Learning Outcomes Framework (intended to 2004 to 22 percent in 2014.9 The American

guide Head Start program design) describes Community Survey identifies people age

English learners in terms of how they may five and up as LEP if they are reported

differ on various indicators and asserts that to speak English less than very well. Only

"continued development of a child's home 6.2 percent of five- to nine-year-olds fell

language in the family and early childhood into that category. Of course, speaking

program is an asset and will support the English very well is only one component of

child's progress in all areas of learning."7 proficiency. School districts typically identify

The Head Start framework also stresses English learner students through a home

that English learners must be allowed to language survey, followed by a more formal

demonstrate knowledge, skills, and abilities assessment of English language proficiency.

in any language (English, their home Not all children whose primary language isn't

language, or both). Finally, state-funded English are identified as English learners.

preschool regulations vary from state to state: Still, in the 2013-14 school year, 16.5

14 of 41 states with state-funded preschool percent of public school students enrolled in

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 161

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa M arkman-P ithers

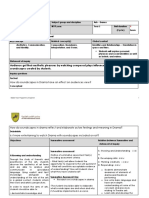

Table 1. Percent of Children Speaking a Language Other than English in the Home and

Percent of Children Identified as English Learners, Select Populations in 2004 and 2014

Percent speaking a language other

than English in the home Percent English learner/LEP

Population Age range 2004 2014 Grade/age range 2004 2014

Head Start 3-4 28.80 28.30

American 5-9 19.34 22.43 5-9 6.83 6.20

Community

Survey

US public K-3 16.5

schools

California 5-9 43.77 43.45 K-3 35.82 36.24

Texas 5-9 31.56 36.61 Pre-K-3 28.50

Florida 5-9 23.79 28.32 Pre-K-3 15.97

Illinois 5-9 20.96 24.69 Pre-K-3 10.96 13.31

New York 5-9 25.56 30.38 Pre-K-3 11.11

Sources: Office of Head Start, "Head Start S

data/psr/2015/services-snapshot-hs-2014-20

204.27: English Language Learner (ELL) Stude

Home Language: 2013-14/' Digest of Educati

asp; CalEdFacts, http://www.cde.ca.gov/re/p

https://rptsvrl.tea.texas.gov/adhocrpt/adlep

fldoe.org/SASPortal/main.do; Illinois State B

Bilingual Education Programs: 2004 Evaluatio

Board of Education, Data Analysis and Accou

SY2013 (2012-2013 School Year) Statistical Re

Education Department, "New York State Data

kindergarten served; New Mexico,

through Texas, Nevada, grade

third and f

that category.10 Colorado round out the top five for the largest

shares of public school students (grades K-12)

English learner students and youn

who are English learners. In table 1, we also

aren't uniformly distributed across

report American Community Survey data

United States. In fact, more than

on the proportion of five- to nine-year-olds

of the US total reside in just five st

whose home language isn't English for the

By far,

California public schools ser

five states with the largest number of English

most English learner students of an

learners, as well as data from these states on

and have the largest share of studen

the proportion of young public school students

are English learners. About one-th

all public-schoolwho are English learners, including

English preschool

learner s

in the nation are enrolled in California students for states other than California.12

schools, and 24 percent of all California Notably, 36 percent of California public-

public school students are English learners school students in kindergarten through third

(see table 2). 11 Texas, Florida, New York, grade are English learners, as are about 30

and Illinois round out the rest of the top percent of Texas prekindergarten through

five for the number of English learners third-grade students.

162 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

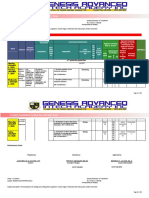

Table 2. Top Five States in Two Measures of English Learner Enrollment, 2013-14

Percentage of total English learner public

US public school school students as a

English learner percentage of total state

State students State student population

California 30.59 California 23.89

Texas 16.42 New Mexico 16.90

Florida 5.78 Texas 15.71

New York 4.89 Nevada 15.49

Illinois 3.79 Colorado 13.49

Sources : National Clearinghouse for E

php, and National Center for Educatio

Level, Grade, and State or Jurisdictio

tables/dtl5_203.40.asp.

Among all Mandarin

English and C

learners, S

far the language most comm

Vietnamese.14 (Y

at home.13 that

Figure some Engl

1 shows th

of all public the home; this

elementary and

English who

learners livespeak

who in mul

e

top 30 as adopted

languages child

reported. A

elementary non-English-spe

and secondary En

students at adoption.)

all The 7

grade levels,

report that language

Spanish is is Span

their h

followed by among

Arabic, Head Sta

Chinese

Figure 1. Most Commonly Re

Public Elementary and Secon

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 163

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

English learners are also likely to come only, but they may also include English-

from poorer families, meaning that they proficient students if they are designed to

have fewer resources at home. In a study make all students proficient in English and

using a nationally representative sample of another language. The CSPR asks states to

children born in the United States in 2001, report on the types of LIEP programs they

researchers reported that 41 percent of use in two categories - English Only or

children growing up in bilingual households English and Another Language. Most states

(those with a primary home language other (43, including the District of Columbia,

than English and frequent exposure to based on our calculations from the 2013-14

two languages) come from families in the CSPR data) report that at least one local

lowest fifth on an index of socioeconomic

education agency makes use of a program in

status, while only 10 percent are in the

the English and Another Language category.

highest fifth.16 In contrast, only 14 percent Eight states (Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii,

of children growing up in households where Missouri, New Hampshire, North Dakota,

English is the primary home language

Vermont, and West Virginia) report having

live in families in the lowest fifth, and 22

nothing but programs in the English Only

percent are in the highest fifth. Similarly, a category.

report using 2013 data from the American

Community Survey indicates that 28 percent The CSPR also asks states to report the

of five- to 17-year-old children growing up number of certified or licensed teachers in

in households where a language other than Title Ill-funded activities and to project

English is spoken are poor, compared to 19 how many more such teachers will be

percent of children growing up in an English- needed in five years. Overall, in the 2013-14

only household.17 The average English school year, there were just over 345,000

learner student faces both the disadvantage licensed or certified teachers in Title Ill-

of coming from a poor family and the funded activities.19 This number was largely

disadvantage of being an English learner unchanged from 2011-12; however, some

in a primarily English-language education states, such as Illinois and Nebraska, more

system. As a result, its hard to distinguish than doubled the number of such teachers

which disadvantage drives worse educational over that two-year span, while the number

outcomes for English learner students. declined elsewhere. In the following five

years, states expected to need around 24

In the 2013-14 school year, states identified

percent more such teachers, on average.

roughly 4,930,000 students (9.8 percent of

total enrollment) as English learners and Why This Matters

reported serving 92 percent of them in

programs funded with Title III grants, based The high school graduation rate for

on data compiled from the Consolidated English learner students was 61 percent

State Performance Report (CSPR).18 The in 2012-13, compared with an overall US

same data show that English learner studentsgraduation rate of 81 percent.20 The gap

are served by many types of Language in high school completion rates doesn't

Instruction Educational Programs (LIEPs), apply directly to young English language

as defined by No Child Left Behind. Such learners because they may become English

programs may serve English learner studentsproficient before reaching high school;

164 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

however, early achievement gaps between data indicate that among students assessed

English learners and their native-English- in Spanish or English, those who were not

speaking peers can still translate into lower proficient in English when they entered

educational attainment. English proficiency kindergarten scored lower in mathematics

and educational attainment are associated in the fall of their kindergarten year than

with higher wages. Using decennial Census did those who were proficient in English.22

data and age at arrival in the United States, This gap is roughly the size of the gap in

researchers have estimated that a person mathematics between white and black

who speaks English poorly earns roughly 33 students in the fall of their kindergarten year.

percent less than one who speaks English By spring 2002 (when most children in the

well.21 However, not all of the relationship study were enrolled in third grade, where all

between English proficiency and wages is students are assessed in English), the gap had

a direct effect of English skills on worker narrowed to about 45 percent of the white-

productivity. The researchers found that the black gap. By spring 2007 (eighth grade),

majority of the earnings gap can be explained the gap in average scores was 28 percent of

by lower levels of educational attainment. the gap between white and black students.

That is, people with greater English Thus, while a test score gap remained

proficiency get more education, explaining a between students who were English learners

large share of the gap in earnings. in kindergarten and others, students who

weren't proficient in English when they

started kindergarten didn't fall further behind

A person who speaks English their peers and, in fact, partially closed the

gap by eighth grade. 23

poorly earns roubily 33

percent less than one who Using the ECLS-K to look at reading

assessment scores by English proficiency

speaks English well.

is somewhat more complicated, because

students are assessed only in English,

Students who are English learners when and thus the pool of students being

they enter kindergarten score consistently compared changes over time.24 Specifically,

lower on tests of mathematics (given in kindergarten students are assessed only if

Spanish or English) and reading (given they score well enough on an exam of English

only in English) than do students who proficiency, whereas all students are assessed

enter kindergarten proficient in English, from third grade on. Not surprisingly,

although the sizes of the test score gaps kindergarten students who are not proficient

are smaller than those between students in English (but proficient enough to take the

with college-graduate versus high school- exam) score lower on the reading assessment

graduate parents, or the gap between white than do kindergarten students who are

and black students (excluding Hispanic proficient in English. The size of the gap

students). Data from the Early Childhood is roughly 70 percent of the gap between

Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of white and black students. The gap widens

1998-99 (ECLS-K) let us compare outcomes somewhat to roughly three-quarters of the

for a representative sample of children who white-black gap in third grade, when all

enrolled in kindergarten in 1998-99. These students are assessed in reading, and narrows

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 165

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 D on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

to 47 percent of the gap between white andpurposes of Title III, the reporting form for

black students by eighth grade. Again, we the CSPR lists five categories within each

see that English learner students continue to

type. Under English Only, the five categories

perform more poorly on reading assessments

are sheltered English instruction, structured

than do students who aren't English learners,

English immersion, specially designed

although we see the gap narrowing betweenacademic instruction delivered in English,

third and eighth grade.25 However, test scorecontent-based English as a second language

gaps remain for both math and reading (ESL), and pull-out ESL; under English

even in eighth grade, suggesting that these and Another Language, the form lists dual

English learner students will be more likelylanguage, two-way immersion, transitional

to drop out of high school and ultimately bilingual, developmental bilingual, and

complete less education. One caveat, of heritage language programs (see box 1 for

course, is that these data represent simple descriptions adapted from those provided

averages and thus don't tell us how much by the National Clearinghouse for English

other student and family characteristics Language Acquisition). We note, however,

beyond English proficiency may contribute that no programs are so clear-cut in practice.

to students' below-average math and reading Different programs have been referred to as

scores. In fact, a recent study using the Earlyadditive or subtractive models, depending

Childhood Longitudinal Study Birth Cohorton the role that the native language plays

(ECLS-B) finds that 75 percent or more in instruction. Additive models add English

of the early (preschool and kindergarten) instruction to native language instruction,

whereas subtractive models focus on

reading score gaps between English learner

children and others can be explained by transitioning English learners to English

differences between the two groups in suchimmersion programs as rapidly as possible

characteristics as mothers education level, and thus subtracting native language

household income, and parents' literacy instruction.27 Another distinction among the

activities in the home.26 English and Another Language programs

is how long a student may participate. Such

How Do We Help Young English programs can be defined as either early exit

Learner Students? or late exit. In early exit bilingual programs,

students transition into an English-only

How can we best help children acquire the classroom within two or three years. In late-

level of English proficiency they need to exit bilingual education programs, students

achieve their potential in classrooms where stay in the program much longer; transition

English is the language of instruction and into a mainstream English program usually

to participate fully in our predominantly doesn't occur until the end of fifth or sixth

English-language society? It's an open grade. Late-exit programs can be found in

question. Models for teaching English both transitional and developmental models.

learner children are often characterized

Within all of these programs, the percentage

as either English immersion (instruction of time dedicated to the primary language

only in English) or bilingual education and to English can vary.28 Transition from

(instruction occurs both in English and in bilingual to mainstream, English-only

the students' native language), but each classrooms and reclassification as former

type includes several broad categories. For English learner depend on a student 's level

166 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

Box 1. Types of English Learner Programs Funded by Title III Grants

English Only Programs

Sheltered English instruction: An instructional approach used to make academic instruction in English

understandable to English learners to help them acquire proficiency in English while achieving in conte

areas. Sheltered English instruction differs from ESL in that English is not taught as a language with a foc

learning the language. Rather, content knowledge and skills are the goals. In the sheltered classroom, t

use simplified language, physical activities, visual aids, and the environment to teach vocabulary for c

development in mathematics, science, social studies, and other subjects.

Structured English immersion: In this program, language-minority students receive all their subject m

instruction in English. The teacher uses a simplified form of English. Students may use their native langu

class; however, the teacher uses only English. The goal is to help language-minority students acquire p

in English while achieving in content areas.

Specially designed academic instruction delivered in English: See structured English immersion.

Content-based English as a second language: This approach to teaching English as a second language

of instructional materials, learning tasks, and classroom techniques from academic content areas as t

for developing language, content, cognitive, and study skills. English is used as the medium of instruct

Pull-out ESL: A program in which English learner students are pulled out of regular, mainstream classr

special instruction in English as a second language.

English and Another Language Programs

Dual language: Also known as two-way immersion or two-way bilingual education, these programs are

to serve both language-minority and language-majority students concurrently. Two language groups ar

together and instruction is delivered through both languages. For example, native English-speakers ma

Spanish as a foreign language while continuing to develop their English literacy skills, and Spanish-spea

English learners may learn English while developing literacy in Spanish. The program seeks to help bot

become biliterate, succeed academically, and develop cross-cultural understanding.

Two-way immersion: See dual language.

Transitional bilingual: An instructional program in which subjects are taught through two languages-

and the native language of the English language learners- and English is taught as a second language. E

language skills, grade promotion, and graduation requirements are emphasized, and the native langua

used as a tool to learn content. The primary purpose of these programs is to facilitate English learner

transition to an all-English instructional environment while receiving academic subject instruction in t

native language to the extent necessary. As proficiency in English increases, instruction in the native l

decreases. Transitional bilingual education programs vary in the amount of native language instruction

and the duration of the program. The programs may be early- or late-exit, depending on the amount o

child may spend in the program.

Developmental bilingual: A program that teaches content through two languages and develops both la

with the goal of bilingualism and biliteracy. May also be referred to as a late-exit program.

Heritage language: The language a person regards as their native, home, and/or ancestral language. In

indigenous languages (for example, Navajo) and immigrant languages (for example, Spanish in the Unit

Source: Adapted from http://www.ncela.us/files/rcd/BE021775/Glossary_of_Terms.pdf.

of English proficiency and the goal of the Arguments for Bilingual Education

program. How proficiency is assessed in

these programs also varies in terms of what Young children (prekindergarten-third

skills are necessary to be considered ready grade) enter school still developing

to transition and what tools are best used to proficiency and literacy skills in their home

assess these skills.29 language, whether its English or another

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 167

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

language. School is where students go to isn't automatic; for transfer to occur, they

strengthen these skills. Young students argue, students need instruction in areas

whose native language isn't English face such as identifying common cognates.33 In

an especially great challenge, as they must addition, the transfer theory relies heavily

continue to develop a strong foundation in on children having a strong foundation in

their native language while trying to learn their native language. Therefore, those

English. Frequently, these students are who support the theory argue that students

called dual language learners , because they(especially young children) should remain

are working on learning two languages at in intensive bilingual programs for a long

the same time. One argument for bilingual time so that they can reach a high level

education is that these young students still of linguistic competence in their native

need help reaching proficiency in their first language. Researchers who support this

language as well as in English. Supporters theory of bilingual education contend that

of this approach also argue that not teaching although such students may gain English

children in both languages is unjust because

proficiency a bit more slowly in the short

it may deny them the benefit of being run, strengthening their native language

bilingual later in life.30 skills will bring better English proficiency in

the long run.34

Young students whose nativeAnother argument for bilingual education is

that students need time to gain proficiency

language isn't English face anin English. Factors involved in English

especially great challenge, asproficiency include oral- and academic-

they must continue to develop language development (that is, the ability

to communicate effectively in academic

a strong foundation in their settings, which typically rely on more

native language while trying formal language structure and vocabulary).

Oral language proficiency in English is

to learn English.

associated with greater academic gains in

English reading achievement, including

reading comprehension and writing, and

In addition, advocates of bilingual education

propose that a relationship exists between academic English proficiency is related to

learning a first and second language, and long-term success in school.35 According

that a strong foundation in a child's first to researchers, English learners typically

language will help in second-language take three to five years to achieve advanced

acquisition.31 Researchers don't completely proficiency in oral English and four to

understand what mechanisms transfer from seven years to develop academic English

one language to another, but some suspect proficiency.36 The speed of language

that skills such as phonological awareness, acquisition depends on both the child and

decoding, and knowledge of letters and environmental factors.37 These researchers

sounds can probably be transferred and that

caution that although students' language

they can help students acquire English.32 development initially progresses somewhat

These researchers caution that although rapidly, progression to higher levels of

certain skills may transfer, such a transfer proficiency is much slower and therefore

168 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

students should have the support and time old; however, the exact age at which such a

they need to fully develop these skills.38 decline occurs has been debated, and some

suggest that we should be thinking in terms

Finally, while working on becoming English

of a "range of age factors" that include an

proficient, English learner students are

interaction between biology (brain plasticity

also trying to meet the same academic

and other neurological changes) and factors

expectations in math, reading, etc., as their

such as exposure and motivation.43 Others

native English-speaking peers. Although further argue that English learners are hurt

such demands vary by age, another argument

by being segregated from their English-

for adopting a bilingual education approach speaking peers, making it harder for them to

is that students will continue progressing assimilate into American society.44 And yet

in academic development while becoming others argue that bilingual education is more

proficient in oral and academic English.39 expensive and that we lack enough qualified

bilingual teachers in all native languages to

Arguments against Bilingual Education

offer high-quality bilingual education. 45

Arguments against bilingual education are

Is Bilingual Education the Same for All

based on the premise that English immersion

Students?

is the most efficient way to acquire English

proficiency and that children whose native Some research suggests that degree of

language is not English should learn English language transfer may vary from language

as quickly as possible to be able to receive to language, depending on the structures

all the benefits available to them in an

of the native and secondary languages in

English-speaking society.40 These researchers question. As a result, bilingual education s

generally don't support the language transfer impact on students may depend on students'

theory, citing research that finds no short- or native languages.46 In a recent correlational

long-run differences in the rate of English study, researchers looked at multiple cohorts

language acquisition between students in of students from a large urban district

English immersion and bilingual education (totaling 13,750) who entered the district in

programs.41 Some advocates of English kindergarten. These students were followed

immersion claim that there's a critical period over time to examine their outcomes in

for language acquisition, and thus the earlier literacy and math. The data were separated

students are exposed to and learn English, by ethnicity to examine differences for

the better. Although scholars argue about Latino and Chinese English learner students.

whether a critical period exists for acquiring The trajectories of the two groups differed.

a second language, few challenge the idea Based on standardized test scores in English

that early exposure to language (in infancy Language Arts (ELA), test scores grew faster

and early childhood) is associated with peak among Latino English learner students

proficiency - particularly in certain aspects enrolled in dual language and bilingual

of language acquisition such as sound classes than among Latino English learner

production and grammar.42 Some researchers students enrolled in English immersion

suggest that we can see a decline in average classes. As a result, average ELA test scores

proficiency in children introduced to a in the seventh grade were higher for Latino

second language as early as four to six years English learner students who were enrolled

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 169

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

in dual language or bilingual classes when serve students and families with a number of

they entered kindergarten than for their different home languages, and they may or

peers enrolled in English immersion classes.

may not have teachers and staff who are also

In contrast, ELA test scores didn't grow fluent in those languages. Therefore, some

any faster among Chinese English learner types of programs, such as dual language

students enrolled in dual language classes immersion, aren't feasible in all schools

than among Chinese English learner studentsor for all students. However, as English

enrolled in English immersion classes. But learners constitute a growing share of US

Chinese English learner students enrolled public school students, it's imperative that we

in a developmental bilingual program develop and adopt programs that serve them

performed worse than their peers enrolled effectively.

in English immersion classes. Researchers

In the sections that follow we examine

suspect that the differences arose because

Spanish and English are more structurally what research has to say about how best to

educate young English learners. Because

similar than Chinese and English.47 Although

the authors attempted to control for parentalof the scope of this issue of Future of

preferences and observable differences Children , we focus on younger children

between students, the students weren't (grades prekindergarten-third grade). We

randomly assigned to the programs, so we also focus mainly on Spanish-speaking

can't rule out the possibility that part of the students, because they represent the largest

difference between Chinese and Latino population of English learners in the United

English learners is explained by which States and have been the subjects of almost

students chose which language programs. all the current research. Where appropriate,

we incorporate other research; however,

our main focus is on children's language and

When it comes to the question literacy development.

of whether to teach English Evaluations and Reviews: Bilingual

learner students in a bilingual versus English Immersion Classes

classroom , it's likely that Numerous studies have compared how bilin-

there isn't a single answer for gual education and English immersion affect

all schools. academic performance and English language

acquisition. The results have been conflict-

ing, leaving most researchers still uncertain

In addition, when it comes to the question about which is the best way to educate

of whether to teach English learner students English learners. These studies vary in their

in a bilingual classroom, its likely that there methodology and quality. Very few can be

isn't a single answer for all schools. Although categorized as experimental or quasi-exper-

the majority of English learner students imental studies that allow us to make casual

speak Spanish as their home language, more conclusions. Further, many correlational

than 50 languages were reported among the studies fail to include appropriate control

top five languages across all states.48 As a variables. Studies that aren't experimental

result, some local education agencies need to or don't include appropriate controls fail to

170 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

consider that the students enrolled in bilin- significantly worse on the state administered

gual or English immersion programs may ELA exam than did English learner stu-

differ in either observable or unobservable dents enrolled in other bilingual and English

characteristics (for example, their degree of immersion programs. However, the authors

exposure to the English language or their lit- were able to follow some cohorts of students

eracy in their native language) that may also as far as seventh grade, and they found

affect outcomes and limit our ability to make evidence that students enrolled in the dual

causal statements. Experimental and quasi- language program caught up to students in

experimental studies confront this problem the other programs by fifth grade. Thus, if

either by random assignment or by relying on we had only the short-run results, we might

sources of random variation that assign some conclude that dual language programs harm

children to bilingual programs and others to students' ELA achievement. Yet the lon-

English immersion programs. ger-run evidence suggests that dual language

programs may be just as effective but take

For the purposes of our review, another

longer to develop students' English language

weakness of many studies is that they typ-

skills, as advocates of bilingual education

ically include children from kindergarten

have hypothesized.

through 12th grade. This factor makes it

hard to answer questions specifically about Language of Instruction for English

children in preschool and the primary grades, Learners in Preschool

whose needs differ from those of older

children. Younger children are still trying The amount of high-quality research on

to gain a strong foundation in their native language of instruction for preschool-aged

language while simultaneously mastering English learners is limited. In a systematic

review of studies conducted between 2000

English, whereas older children are likely to

and 2011, researchers identified 25 that

have higher levels of literacy in their native

language but face greater academic demands looked at education interventions for English

and tasks that require more abstract thinking learner children from birth to five years old.50

and higher-order language manipulation. These studies primarily focused on Span-

ish-speaking children between three and

In addition, many existing studies are five years old, and they included studies on

short-term, and short-term studies, whether professional development, curricular pro-

experimental or correlational, may obscure grams, and supplemental instruction, not just

benefits that appear only in the long term. those that specifically investigated the impact

A recent non-experimental study highlights of language of instruction. The reviewers

this problem. This study focused on English concluded that current research studies make

learner students in a single district who it difficult to disentangle the effects of a cer-

entered school in kindergarten, and although tain curriculum or learning strategy from the

the students weren't randomly assigned to effects of language of instruction.

different groups, the researchers controlled

for parental preferences and other observed Two recent experimental studies, included in

differences between students in the different the review, look at how bilingual education

programs.49 In second grade, the authors affects young students' language develop-

found that dual language students scored ment. These two studies randomly assigned

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 171

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

preschool students to bilingual or English curriculum plus supplemental, small-group

immersion classes and found that over literacy instruction using a transitional

the course of one year, preschool students Spanish/English model. Students who

in bilingual classes had better outcomes received the supplemental instruction in

overall in Spanish and similar outcomes in either English alone or Spanish and English

English compared to their peers in English performed significantly better in emergent

immersion classes. These studies specifically

literacy skills in both languages than did

investigated receptive and expressive vocab-those who received only the traditional cur-

ulary, phonological awareness, and rhyming, riculum. Moreover, those who received the

and they found statistically significant gains transitional Spanish/English literacy sup-

in Spanish for the bilingual group. Combined

plement performed significantly better than

with the finding that there were no overall the other two groups in emergent literacy

significant differences in English achieve- skills in Spanish. Students in the transitional

ment between the two groups, these resultsSpanish/English group also performed better

in English in two areas (vocabulary and print

suggest that providing less instruction time in

knowledge); the researchers suggest that this

English didn't compromise students' English

language development but did help the finding may indicate some level of language

transfer.53

students retain their native language skills.51

Notably, however, these experiments were

based on small samples (150 students in one

study and 31 in the other) and considered The preschool evidence finds

only short-run outcomes after one year of

in favor of using bilingual

bilingual or English immersion education,

so the results may not apply to other popu-

education programs - with

lations and longer-term impacts. In a longi- the caveat that the studies are

tudinal follow-up of the smaller experiment,

relatively small and generally

researchers found that in second grade,

overall performance in English among stu- apply only to outcomes after

one

dents in the bilingual program was still equal year.

to that of students in the English immersion

program.52

In summary, studies of bilingual programs

Going beyond assigning students to English-

for preschool students find that students

only or bilingual classrooms, another randomly assigned to a bilingual program

experiment looked at how bilingual sup- perform equally well on tests of English

plemental-language instruction affected achievement as their counterparts assigned

students' language development. In one to an English-only program, and in the case

randomized evaluation, 94 Spanish-speak- of one study, outperform their counterparts

ing preschool students were assigned to onein some English literacy areas. Further, the

of three groups - a traditional curriculum preschool evaluations consistently find that

control group; a group that received the students randomly assigned to bilingual

traditional curriculum plus supplemental, programs outperform English-only program

small-group literacy instruction in English; students on tests of Spanish achievement.

or a group that received the traditional Thus, the preschool evidence finds in favor

172 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

of using bilingual education programs. The Center for Research on Education, Diver-

caveats are that the studies are relatively sity and Excellence) concluded that teaching

small and generally apply only to outcomes students to read in their first language pro-

after one year. motes higher levels of reading achievement

in English. 56 Similarly, a 2012 meta-analysis

Language of Instruction for English found that bilingual reading programs for

Learners in Grades K-12

elementary school students are more effec-

tive than English-only reading programs.57

More studies look at the effectiveness of

At the same time, the authors cautioned that

bilingual education for grades K-12 than for

many of the reviewed studies were short-

younger children; however, they are much

term and that the researchers didn't assign

more likely to rely on observational data

students randomly to one group or another.

than on experimental or quasi-experimen- For these reasons, the authors called for

tal strategies. Starting in the 1980s, a series

additional research using randomized

of reviews and meta-analyses attempted to

designs to assess long-term outcomes. In

look at studies systematically and determine contrast, another recent review that focused

the effectiveness of bilingual education for

only on experimental and quasi-experimen-

grades K-12.54 Again, the conclusions of

tal studies was less optimistic about bilingual

these reviews range from the finding that

education; it concluded that bilingual educa-

bilingual education makes no difference in tion doesn't seem to be systematically better

outcomes for English learners to the finding

or worse for improving English proficiency.58

that bilingual education is an effective way Overall, then, studies that focus on children

to educate English learners. The differences in grades K-12 suggest that bilingual edu-

depend on factors such as the types of studies cation is at least as effective as English-only

that were deemed appropriate for review programs.

based on methodology, goals, and how bilin-

gual education was defined; what outcomes Randomized evaluations can allow us to

the reviewers were seeking to examine make causal statements because they help

ensure that differences in outcomes aren't

(English proficiency, native language profi-

ciency, or acquisition of content material); driven by differences in which students

and how the reviewers defined effective- receive which type of program. As we noted

ness.55 Some researchers deem a program to when we discussed preschool studies, few

be effective if students in a bilingual program long-term randomized evaluations of bilin-

learned as much English as the students in angual instruction have been conducted. One

English immersion group and retained their exception is a recent evaluation of programs

in six schools in different states that ran-

native language. Others find a program to be

effective only if the students in a bilingual domly assigned Spanish-dominant kinder-

program learned significantly more English garteners to either bilingual or English

than those in an English immersion program.immersion programs. These students were

then followed for up to four years. In all

More recent meta-analyses have reached cases, reading instruction used the same

a similar range of conclusions. Two major curriculum either in English or Spanish.

reviews conducted in 2006 (one by the The study found that first-grade students in

National Literacy Panel and the other by the the bilingual classes had significantly higher

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 173

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

scores in Spanish and significantly worse math achievement (in assessments given in

English) between students based on their

scores in English than did students in English

immersion classes. By fourth grade, all the eligibility for the bilingual program.60 One

students had transitioned to an English critique of this study is that it could assess

immersion classroom and no significant dif- the impact of bilingual education only on

ferences were found in English or Spanish, students at the margin of qualifying for

with the exception that students assigned to bilingual education. Therefore, although

the bilingual class scored significantly higherbilingual education in this district might not

on a Spanish comprehension measure. The affect reading and math achievement scores

authors concluded that all the fourth-grade for marginal English learner students, it

students were fully bilingual, as measured bymight help English learner students with very

their scores on receptive vocabulary, and thatlow levels of English proficiency. Further,

language of instruction wasn't a factor in howthe study couldn't assess impacts on native

their English proficiency grew - all the stu- language achievement because it relied on

dents made similar gains in English language

administrative data consisting of reading and

skills (and perhaps decreased in Spanish math achievement tests given in English.

skills) over time.59

Regression discontinuity has also been

Similar findings have been found in more used to assess the rules used to determine

recent quasi-experimental studies. These whether students should be classified

studies use a regression discontinuity as English learners (and are therefore

design to evaluate the impact of bilingual entitled to associated services) or assigned

education. Regression discontinuity exploitsto mainstream English-language classes. A

variation in treatment of English learner recent study used data from the Los Angeles

students generated by policy rules to Unified School District in this way to assess

compare students or programs just above rules for assigning kindergarten students to

or below a threshold that determines the English learner status and for reclassifying

type of program students receive. As a older students as English proficient.61 In this

result, it generates more opportunities to case, a difference in outcomes for students

study bilingual programs by using plausibly at the margin of the test score cutoff was

random variation that is already occurring interpreted as evidence that the test score

"naturally," thus adding to the information cutoff was set at the optimal level. The

provided by the few studies that have study's author concluded that we would see

randomly assigned students to different achievement gains if more kindergarten

program types. For example, in one large students were classified as English

urban district a researcher compared learners and if students were transferred

students in third through eighth grade to mainstream English-language classes at

who were just above and below the cutoff an earlier age. As with small experimental

score in English language proficiency to be studies, however, the caveat is that these

eligible for bilingual education. Students results apply specifically to the Los Angeles

just below the cutoff score were eligible for Unified School District and the English

bilingual education, while those just above learner programs it offers. The findings don't

the cutoff were not. The researcher found necessarily apply outside California or even

no significant differences in reading or to other districts in the state.

174 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

Finally, regression discontinuity has been

used to study what happens to both English

English learner children

learner and non-English learner students

when English learner students are offered may benefit at least as much

bilingual education. One study investigated from high-quality preschool

bilingual education in the 261 school

districts in Texas most likely to be affected

programs as other children

by the state s bilingual education law. By law, do, if not more so.

Texas districts must offer bilingual education

when they have 20 or more English learner

students in a particular grade and language; Classroom Quality

if there are fewer than 20, the district may

Some researchers argue that classroom

choose either bilingual education or ESL.

quality may be more important for young

Using regression discontinuity, researchers

English learners' educational outcomes

compared student outcomes in districts

than language of instruction. Research has

that were just above the 20-student cutoff

shown that participating in high-quality

(and therefore more likely to provide a

preschool programs has large benefits for

bilingual program) to student outcomes in

all children, and the limited research that

districts just below the cutoff. They found

focuses on preschool quality and English

no significant differences on standardized

learner children indicates that they may

test scores for English learner students in

benefit at least as much from high-quality

districts that were required to offer bilingual

preschool programs as other children do,

programs compared to districts that offered

if not more so.63 Of course, preschool-aged

ESL programs. However, in districts

English learners likely need teachers who

required to provide bilingual education,

are trained to work with such students,

native English speakers' standardized test

so a high-quality preschool designed for

scores were significantly higher.62 Again, the

non-English learner students probably isn't

study relied on district standardized tests

enough. 64 High-quality preschool teachers

given in English, and therefore the authors

for English learners may need to understand

couldn't estimate impacts on achievement

language theory and pedagogy related to

in the English learner students' native

first and second language acquisition, be

language - in this case, Spanish.

sensitive to the role that culture plays in

Overall, meta-analyses, randomized language and overall development, and be

evaluations, and regression discontinuity able to foster positive peer relationships and

studies find that bilingual education parental engagement. Some researchers

has neutral to positive effects on K-12 who investigate the effectiveness of bilingual

students' English language development. education programs suggest that the varying

They also offer some evidence that rules quality of these programs may explain why

for when to transfer English learners into bilingual education is not always more

mainstream classes may not be optimal and successful than English immersion.65 One

that bilingual education may have spillover recent correlational study examined how

effects on non-English learner students that classroom quality moderates the relationship

often aren't taken into consideration. between instructional language and child

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 175

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

outcomes. It found that the amount of instruction to the child's developing levels

Spanish instruction was positively correlated of language proficiency;

with children's outcomes in high-quality

classrooms with more responsive and 2. Use focused, small-group activities to give

English learner children opportunities to

sensitive teachers, but negatively correlated

with children's outcomes in low-quality

respond to questions and receive more

individualized instruction;

classrooms.66 (See the article in this issue

by Robert Pianta, Jason Downer, and

3. Provide explicit vocabulary instruction;

Bridget Hamre for more about teacher

responsiveness and classroom quality). 4. Use academic English in instruction to

further develop academic English, and

What can teachers who work with young

provide explicit opportunities to learn

bilingual children do to improve instruction?

academic English such as the words for

Instruction in phonemic awareness has

mathematical concepts; and

been found to help all children with early

literacy development. As children's language 5. Promote socioemotional development

skills grow stronger, recommendations for by creating positive teacher-student

tailoring this instruction to English learners relationships and facilitating peer

include providing more concentrated work interactions.

on English phonemes or combinations of

Conclusions

phonemes that don't exist in the students'

native language.67 Vocabulary, which is

As a whole, the research evidence is

associated with reading comprehension,

still inconclusive regarding the overall

is also an important aspect of language effectiveness of different forms of instruction

instruction. Students whose native language

for English learners. Which form of

isn't English typically enter school with a

instruction is most effective is a challenging

limited vocabulary of English words, in terms

question to answer, even with the most

of both breadth (number) and depth of word

rigorous research strategies. This uncertainty

knowledge (knowing many things about

stems in part from the fact that researchers

a word, such as its meaning and semantic

and policymakers don't share a consensus on

associations).68 Thus researchers recommend

the ultimate goal of education for English

that teachers target depth of word knowledge

learners. Is the goal to help English learner

when working with English learners and

students become truly bilingual or to help

take advantage of students' first language in

them become proficient in the English

building vocabulary, especially if the language

language? Evidence from meta-analyses,

shares cognates with English.69

with the finding that teaching children

A recent review of research-based practices to read in their native language improves

for young English learner students highlights reading achievement in English, leans in

five practices to help support English learner favor of bilingual education in the early years.

students in the classroom:70 However, the studies underlying these meta-

analyses are generally non-experimental,

1. Use frequent assessments in both a and therefore the effects we see may be

child's first and second language to adapt caused by factors other than the language of

176 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

instruction. Recent evidence from small, on Spanish-speaking students, because

randomized evaluations at the preschool roughly three-quarters of public-school

level suggests that English learners achieve English learner students report Spanish

about the same English proficiency whether as their home language. However, US

they're placed in bilingual or English immigration patterns have shifted in

immersion programs. Furthermore, even recent years, with more immigrants

if students enrolled in bilingual classes coming from Asia and fewer coming from

don't outperform their peers enrolled in Mexico.72 Existing research on bilingual

non-bilingual classes in terms of English education may not apply to a growing

achievement, they do outperform their population of English learner students

peers in Spanish-language achievement. from Asian countries. Thus, additional

research that looks simply at the impact of

Beyond the question of whether bilingual

"bilingual" education versus "immersion"

programs do better than immersion

isn't likely to offer school districts the

programs at improving language proficiency

kind of guidance they need to craft truly

for English learners, the optimal design

effective programs for English learners.

of bilingual programs isn't clear. Which

approach or combination of approaches Meanwhile, several researchers have

is most effective in moving English argued for greater attention to the quality

learners to English proficiency? We don't rather than the language of instruction.73

know, for example, whether curricular or

If a setting can offer a high-quality

supplemental bilingual programs are most

program with a bilingual teacher, then

effective for student achievement. Nor are

the research evidence suggests that at

we certain how quickly students should the least, students won't be harmed in

be transitioned from bilingual to English

terms of learning English, and they may

immersion classrooms. Should students

be able to retain their native language

enter an English immersion program as

skills. However, if districts can't provide

soon as possible, or should they stay in a

a high-quality bilingual program, schools

dual language classroom until they have a

may be better off working to increase

strong foundation in their native language

classroom quality generally or exploring

(early- versus late-exit bilingual programs)?

supplemental bilingual programs rather

Other important issues to consider

than trying to ensure that students have

include the teacher workforce in various

access to a fully bilingual education.

languages and the benefits and costs of

Overall, if the goal is to help English

bilingual education for non-English learner

learners become proficient in English,

students.71 Districts also need to keep in

then educators and policymakers must

mind that bilingual education may be more

keep in mind that bilingual education is

costly than English immersion programs,

but one tool and that other factors also

may increase segregation, and may be

infeasible for some schools and some deserve attention, including the quality of

instruction, supplemental programs, and

languages.

the family and community environment

Another source of uncertainty is that that are critical for a young student's

existing US research has largely focused success.

VOL. 26 / NO. 2 / FALL 2016 177

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lisa Barrow and Lisa Markman-Pithers

ENDNOTES

1. Ellen Białystok and Michelle M. Martin, "Attention and Inhibition in Bilingual Child

from the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task," Developmental Science 7 (2004): 325-

10.1111/j.l467-7687.2004.00351.x; Raluca Barac et al., "The Cognitive Development

Language Learners: A Critical Review," Early Childhood Research Quarterly 29 (2014

10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.02.003; Stephanie M. Carlson and Andrew N. Meltzoff, "Bilingu

and Executive Functioning in Young Children," Developmental Science 11 (2008): 282

10.111 1/j . 1467-7687.2008.00675.X.

2. Fergus I. M. Craik, Ellen Białystok, and Morris Freedman, "Delaying the Onset of A

Disease: Bilingualism as a Form of Cognitive Reserve," Neurology 75 (2010): 1726-29,

WNL.0b013e3181fc2alc.

3. For a broader discussion of these historical changes in laws and attitudes, see Carlos J. Ovando, "Bilingual

Education in the United States: Historical Development and Current Issues," Bilingual Research Journal

27 (2003): 1-24, doi: 10.1080/15235882.2003.10162589, and James Crawford, "Language Politics in the

U.S.A.: The Paradox of Bilingual Education," Social Justice 3, no. 3 (1998): 55-69.

4. Office of Civil Rights, "Ensuring English Learner Students Can Participate Meaningfully and Equally in

E ducational Programs , " http ://www2 . ed . gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/dcl-factsheet-el-students-20 1501.

pdf.

5. Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015, S. 1177, 114th Congress, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-

1 14s 1 177enr/pdf/BILLS- 1 14s 1 177enr.pdf.

6. Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, H.R. 1429, 110th Congress, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.

hhs.gov/hslc/standards/law/HS_ACT_PL_110-134.pdf.

7. Office of Head Start, Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework: Ages Birth to 5 (Washington, DC:

Administration for Children and Families, 2015), https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/hs/sr/approach/pdf/ohs-

framework.pdf.

8. Authors' calculations based on W. Steven Barnett et al., The State of Preschool 2014: State Preschool

Yearbook (New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research, 2015), http://nieer.org/

sites/nieer/files/Yearbook2014_full3.pdf. Categories are not mutually exclusive.

9. Office of Head Start, "Head Start Services Snapshot: National (2014-2015)," http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.

gov/hslc/data/psr/2015/services-snapshot-hs-2014-2015.pdf. Authors' calculations based on data from the

American Community Survey (ACS).

10. US Department of Education, "Table 204.27: English Language Learner (ELL) Students Enrolled in

Public Elementary and Secondary Schools, by Grade and Home Language: 2013-14," Digest of Education

Statistics, accessed January 4, 2016, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/dl5/tables/dtl5_204.27.asp.

11. Authors' calculations based on EL counts from National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition

(NCELA), "Title III State Profiles," accessed March 29, 2016, http://www.ncela.us/t3sis/index.php, and

enrollment counts from National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), "Table 203.40: Enrollment in

Public Elementary and Secondary Schools, by Level, Grade, and State or Jurisdiction: Fall 2013," Digest of

Education Statistics , accessed March 29, 2016, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/dl5/tables/dtl5_203.40.

asp.

178 THE FUTURE OF CHILDREN

This content downloaded from

203.198.184.26 on Mon, 05 Dec 2022 04:12:21 976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Supporting Young English Learners in the United States

12. State-level statistics based on authors' calculations using data from: California Department of Education,

"CalEdFacts," accessed January 8, 2016, http://www.cde.ca.gov/re/pn/fb/index.asp; Texas Education

Agency, "ELL Student Reports by Category and Grade," accessed January 8, 2016, https://rptsvrl.tea.

texas.gov/adhocrpt/adlepcg.html; Florida Department of Education, "Florida EDStats," accessed March

8, 2016, https://edstats.fldoe.org/SASPortal/main.do; Illinois State Board of Education, Data Analysis and

Progress Reporting Division, Illinois Bilingual Education Programs: 2004 Evaluation Report (Springfield,

IL: Illinois State Board of Education, 2005), http://www.isbe.state.il.us/research/pdfs/ell_stu-prog_

eval_rpt04.pdf; Illinois State Board of Education, Data Analysis and Accountability Division, Bilingual

Education Programs and English Learners in Illinois: SY 2013 (2012-2013 School Year) Statistical Report

(Springfield, IL: Illinois State Board of Education, 2015), http://isbe.state.il.us/research/pdfs/el-program-

stat-rptl3.pdf; and New York State Education Department, "New York State Data," accessed January 8,

2016, http://data.nysed.gov/.

13. Office of English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement, and Academic Achievement for Limited

English Proficient Students, Biennial Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Title III State

Formula Grant Program: School Years 2010-12 (Washington, DC: US Department of Education, 2015),

http://ncela.us/files/uploads/3/Biennial_Report_1012.pdf.

14. US Department of Education, "Table 204.27."

15. Office of Head Start, "Services Snapshot."

16. Li Feng, Yunwei Gai, and Xiaoning Chen, "Family Learning Environment and Early Literacy: A

Comparison of Bilingual and Monolingual Children," Economics of Education Review 39 (2014): 110-30,

doi: 10. 1016/j.econedurev.2013. 12.005.

17. Child Trends DATABANK, Indicators on Children and Youth: Dual Language Learners, November 2014,

accessed March 29, 2016, http://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=dual-language-learners.

18. Authors' calculations based on NCELA, Title III State Profiles and NCES, "Table 203.40."

19. Authors' calculations based on 2013-14 CSPR data.

20. National Center for Education Statistics, "Table 219.46: Public High School 4-Year Adjusted Cohort