Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Foot

Uploaded by

sai calderCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Foot

Uploaded by

sai calderCopyright:

Available Formats

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in

Article Talk Read View source View history Search Wikipedia

Foot

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Main page This article is about the anatomical structure. For the unit of measure, see Foot (unit). For other uses, see Foot (disambiguation).

Contents

This article uses anatomical terminology.

Current events

Random article The foot (plural feet) is an anatomical structure found in many vertebrates. It is the terminal portion of

About Wikipedia

Foot

a limb which bears weight and allows locomotion. In many animals with feet, the foot is a separate

Contact us

organ at the terminal part of the leg made up of one or more segments or bones, generally including

Donate

claws or nails.

Contribute

Contents [hide]

Help

Community portal 1 Etymology

Recent changes 2 Structure

Upload file 2.1 Bones

2.2 Arches Details

Tools

2.3 Muscles Artery dorsalis pedis, medial plantar, lateral

What links here plantar

2.3.1 Extrinsic

Related changes

2.3.2 Intrinsic Nerve medial plantar, lateral plantar, deep

Special pages

fibular, superficial fibular

Permanent link 3 Clinical significance

Identifiers

Page information 4 Pronation

Cite this page 5 Society and culture Latin Pes

Wikidata item 6 Other animals MeSH D005528

7 Metaphorical and cultural usage TA A01.1.00.040

Print/export

8 See also FMA 9664

Download as PDF

9 References Anatomical terminology

Printable version

[edit on Wikidata]

9.1 Bibliography

In other projects 10 External links

Wikimedia Commons

Wikiquote

Etymology

Languages

ا The word "foot", in the sense of meaning the "terminal part of the leg of a vertebrate animal" comes from "Old English fot "foot," from Proto-

Español Germanic *fot (source also of Old Frisian fot, Old Saxon fot, Old Norse fotr, Danish fod, Swedish fot, Dutch voet, Old High German fuoz, German

ह ी Fuß, Gothic fotus "foot"), from PIE root *ped- "foot." [1] The "plural form feet is an instance of i-mutation." [1]

Bahasa Indonesia

Bahasa Melayu

Português

Structure

Русский The human foot is a strong and complex mechanical structure containing 26 bones, 33 joints (20 of which are

اردو actively articulated), and more than a hundred muscles, tendons, and ligaments.[2] The joints of the foot are the

中⽂ ankle and subtalar joint and the interphalangeal articulations of the foot. An anthropometric study of 1197 North

110 more American adult Caucasian males (mean age 35.5 years) found that a man's foot length was 26.3 cm with a

Edit links standard deviation of 1.2 cm.[3]

The foot can be subdivided into the hindfoot, the midfoot, and the forefoot:

The hindfoot is composed of the talus (or ankle bone) and the calcaneus (or heel bone). The two long bones of the

lower leg, the tibia and fibula, are connected to the top of the talus to form the ankle. Connected to the talus at the

subtalar joint, the calcaneus, the largest bone of the foot, is cushioned underneath by a layer of fat.[2]

The five irregular bones of the midfoot, the cuboid, navicular, and three cuneiform bones, form the arches of the

foot which serves as a shock absorber. The midfoot is connected to the hind- and fore-foot by muscles and the

plantar fascia.[2] The feet of a newborn

infant.

The forefoot is composed of five toes and the corresponding five proximal long bones forming the metatarsus.

Similar to the fingers of the hand, the bones of the toes are called phalanges and the big toe has two

phalanges while the other four toes have three phalanges each. The joints between the phalanges are

called interphalangeal and those between the metatarsus and phalanges are called metatarsophalangeal

(MTP).[2]

Both the midfoot and forefoot constitute the dorsum (the area facing upwards while standing) and the

planum (the area facing downwards while standing).

The instep is the arched part of the top of the foot between the toes and the ankle.

Bones

A woman's foot, decorated with nail

tibia, fibula

polish and henna, and wearing a metti

tarsus (7): talus, calcaneus, cuneiformes (3), cuboid, and navicular (toe ring) on the second toe, for her

metatarsus (5): first, second, third, fourth, and fifth metatarsal bone wedding.

phalanges (14)

There can be many sesamoid bones near the metatarsophalangeal joints, although they are only regularly present

in the distal portion of the first metatarsal bone.[4]

Arches

Main article: Arches of the foot

The human foot has two longitudinal arches and a transverse arch maintained by the interlocking shapes of the foot

bones, strong ligaments, and pulling muscles during activity. The slight mobility of these arches when weight is

applied to and removed from the foot makes walking and running more economical in terms of energy. As can be

examined in a footprint, the medial longitudinal arch curves above the ground. This arch stretches from the heel

bone over the "keystone" ankle bone to the three medial metatarsals. In contrast, the lateral longitudinal arch is

very low. With the cuboid serving as its keystone, it redistributes part of the weight to the calcaneus and the distal

end of the fifth metatarsal. The two longitudinal arches serve as pillars for the transverse arch which run obliquely

across the tarsometatarsal joints. Excessive strain on the tendons and ligaments of the feet can result in fallen

arches or flat feet.[5]

Muscles

Illustration of bones in

The muscles acting on the foot can be classified into extrinsic muscles, those originating on the anterior or posterior lower leg and foot.

aspect of the lower leg, and intrinsic muscles, originating on the dorsal (top) or plantar (base) aspects of the foot.

Extrinsic

All muscles originating on the lower leg except the popliteus muscle are attached to the bones of the foot. The tibia and fibula

and the interosseous membrane separate these muscles into anterior and posterior groups, in their turn subdivided into

subgroups and layers. [6]

Anterior group

Extensor group: tibialis anterior originates on the proximal half of the tibia and the interosseous membrane and is inserted near

the tarsometatarsal joint of the first digit. In the non-weight-bearing leg tibialis anterior flexes the foot dorsally and lift its medial

edge (supination). In the weight-bearing leg it brings the leg towards the back of the foot, like in rapid walking. Extensor

digitorum longus arises on the lateral tibial condyle and along the fibula to be inserted on the second to fifth digits and

proximally on the fifth metatarsal. The extensor digitorum longus acts similar to the tibialis anterior except that it also dorsiflexes

the digits. Extensor hallucis longus originates medially on the fibula and is inserted on the first digit. As the name implies it

dorsiflexes the big toe and also acts on the ankle in the unstressed leg. In the weight-bearing leg it acts similar to the tibialis

anterior. [7]

Peroneal group: peroneus longus arises on the proximal aspect of the fibula and peroneus brevis below it on the same bone.

Together, their tendons pass behind the lateral malleolus. Distally, peroneus longus crosses the plantar side of the foot to reach Anterior leg

its insertion on the first tarsometatarsal joint, while peroneus brevis reaches the proximal part of the fifth metatarsal. These two muscles.

muscles are the strongest pronators and aid in plantar flexion. Longus also acts like a bowstring that braces the transverse

arch of the foot. [8]

Posterior group

The superficial layer of posterior leg muscles is formed by the triceps surae and the plantaris. The triceps surae

consists of the soleus and the two heads of the gastrocnemius. The heads of gastrocnemius arise on the femur,

proximal to the condyles, and soleus arises on the proximal dorsal parts of the tibia and fibula. The tendons of

these muscles merge to be inserted onto the calcaneus as the Achilles tendon. Plantaris originates on the femur

proximal to the lateral head of the gastrocnemius and its long tendon is embedded medially into the Achilles

tendon. The triceps surae is the primary plantar flexor and its strength becomes most obvious during ballet

dancing. It is fully activated only with the knee extended because the gastrocnemius is shortened during knee

flexion. During walking it not only lifts the heel, but also flexes the knee, assisted by the plantaris.[9]

In the deep layer of posterior muscles tibialis posterior arises proximally on the back of the interosseous

membrane and adjoining bones and divides into two parts in the sole of the foot to attach to the tarsus. In the

non-weight-bearing leg, it produces plantar flexion and supination, and, in the weight-bearing leg, it proximates

the heel to the calf. flexor hallucis longus arises on the back of the fibula (i.e. on the lateral side), and its relatively

thick muscle belly extends distally down to the flexor retinaculum where it passes over to the medial side to

stretch across the sole to the distal phalanx of the first digit. The popliteus is also part of this group, but, with its

oblique course across the back of the knee, does not act on the foot. [10] Deep and superficial layers of

posterior leg muscles

Intrinsic

On the back (top) of the foot, the tendons of extensor digitorum brevis and extensor hallucis brevis lie deep to the system of long extrinsic extensor

tendons. They both arise on the calcaneus and extend into the dorsal aponeurosis of digits one to four, just beyond the penultimate joints. They act

to dorsiflex the digits. [11]

Similar to the intrinsic muscles of the hand, there are three groups of muscles in the sole of foot,

those of the first and last digits, and a central group:

Muscles of the big toe: abductor hallucis stretches medially along the border of the sole, from the

calcaneus to the first digit. Below its tendon, the tendons of the long flexors pass through the

tarsal canal. It is an abductor and a weak flexor, and also helps maintain the arch of the foot.

flexor hallucis brevis arises on the medial cuneiform bone and related ligaments and tendons. An

important plantar flexor, it is crucial for ballet dancing. Both these muscles are inserted with two

heads proximally and distally to the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Adductor hallucis is part of

this group, though it originally formed a separate system (see contrahens.) It has two heads, the

oblique head originating obliquely across the central part of the midfoot, and the transverse head

originating near the metatarsophalangeal joints of digits five to three. Both heads are inserted

Plantar aspects of foot, varying depths (superficial

into the lateral sesamoid bone of the first digit. Adductor hallucis acts as a tensor of the plantar

to deep)

arches and also adducts the big toe and then might plantar flex the proximal phalanx. [12]

Muscles of the little toe: Stretching laterally from the calcaneus to the proximal phalanx of the fifth

digit, abductor digiti minimi form the lateral margin of the foot and is the largest of the muscles of the fifth digit. Arising from the base of the fifth

metatarsal, flexor digiti minimi is inserted together with abductor on the first phalanx. Often absent, opponens digiti minimi originates near the cuboid

bone and is inserted on the fifth metatarsal bone. These three muscles act to support the arch of the foot and to plantar flex the fifth digit. [13]

Central muscle group: The four lumbricals arise on the medial side of the tendons of flexor digitorum longus

and are inserted on the medial margins of the proximal phalanges. Quadratus plantae originates with two

slips from the lateral and medial margins of the calcaneus and inserts into the lateral margin of the flexor

digitorum tendon. It is also known as flexor accessorius. Flexor digitorum brevis arise inferiorly on the

calcaneus and its three tendons are inserted into the middle phalanges of digits two to four (sometimes also

the fifth digit). These tendons divide before their insertions and the tendons of flexor digitorum longus pass

through these divisions. Flexor digitorum brevis flexes the middle phalanges. It is occasionally absent.

Between the toes, the dorsal and plantar interossei stretch from the metatarsals to the proximal phalanges of

digits two to five. The plantar interossei adducts and the dorsal interossei abducts these digits and are also

plantar flexors at the metatarsophalangeal joints. [14] Central muscles of foot

Clinical significance

Main article: Diseases of the foot

Due to their position and function, feet are exposed to a variety of potential infections and injuries, including athlete's foot, bunions, ingrown toenails,

Morton's neuroma, plantar fasciitis, plantar warts and stress fractures. In addition, there are several genetic disorders that can affect the shape and

function of the feet, including a club foot or flat feet.

This leaves humans more vulnerable to medical problems that are caused by poor leg and foot alignments. Also, the wearing of shoes, sneakers

and boots can impede proper alignment and movement within the ankle and foot. For example, High-heeled footwear are known to throw off the

natural weight balance (this can also affect the lower back). For the sake of posture, flat soles with no heels are advised.

A doctor who specializes in the treatment of the feet practices podiatry and is called a podiatrist. A pedorthist specializes in the use and modification

of footwear to treat problems related to the lower limbs.

Fractures of the foot include:

Lisfranc fracture – in which one or all of the metatarsals are displaced from the tarsus[15]

Jones fracture – a fracture of the fifth metatarsal

March fracture – a fracture of the distal third of one of the metatarsals occurring because of recurrent stress

Calcaneal fracture

Foot sweat is the major cause of foot odor. Sweat itself is odorless, but it creates a beneficial environment for certain bacteria to grow and produce

bad-smelling substances.

Pronation

Main article: Pronation of the foot

In anatomy, pronation is a rotational movement of the forearm (at the radioulnar joint) or foot (at the subtalar and talocalcaneonavicular joints).

Pronation of the foot refers to how the body distributes weight as it cycles through the gait. During the gait cycle the foot can pronate in many

different ways based on rearfoot and forefoot function. Types of pronation include neutral pronation, underpronation (supination), and overpronation.

Neutral pronation

An individual who neutrally pronates initially strikes the ground on the lateral side of the heel. As the individual transfers weight from the heel to the

metatarsus, the foot will roll in a medial direction, such that the weight is distributed evenly across the metatarsus. In this stage of the gait, the knee

will generally, but not always, track directly over the hallux.

This rolling inwards motion as the foot progresses from heel to toe is the way that the body naturally absorbs shock. Neutral pronation is the most

ideal, efficient type of gait when using a heel strike gait; in a forefoot strike, the body absorbs shock instead via flexation of the foot.

Overpronation

As with a neutral pronator, an individual who overpronates initially strikes the ground on the lateral side of the heel. As the individual transfers weight

from the heel to the metatarsus, however, the foot will roll too far in a medial direction, such that the weight is distributed unevenly across the

metatarsus, with excessive weight borne on the hallux. In this stage of the gait, the knee will generally, but not always, track inwards.

An overpronator does not absorb shock efficiently. Imagine someone jumping onto a diving board, but the board is so flimsy that when it is struck, it

bends and allows the person to plunge straight down into the water instead of back into the air. Similarly, an overpronator's arches will collapse, or

the ankles will roll inwards (or a combination of the two) as they cycle through the gait. An individual whose bone structure involves external rotation

at the hip, knee, or ankle will be more likely to overpronate than one whose bone structure has internal rotation or central alignment. An individual

who overpronates tends to wear down their running shoes on the medial (inside) side of the shoe towards the toe area.[16]

When choosing a running or walking shoe, a person with overpronation can choose shoes that have good inside support—usually by strong

material at the inside sole and arch of the shoe. It is usually visible. The inside support area is marked by strong greyish material to support the

weight when a person lands on the outside foot and then roll onto the inside foot.

Underpronation (supination)

An individual who underpronates also initially strikes the ground on the lateral side of the heel. As the

individual transfers weight from the heel to the metatarsus, the foot will not roll far enough in a medial

direction. The weight is distributed unevenly across the metatarsus, with excessive weight borne on the fifth

metatarsal, towards the lateral side of the foot. In this stage of the gait, the knee will generally, but not

always, track laterally of the hallux.

Like an overpronator, an underpronator does not absorb shock efficiently – but for the opposite reason. The

underpronated foot is like a diving board that, instead of failing to spring someone in the air because it is Underpronation of foot

too flimsy, fails to do so because it is too rigid. There is virtually no give. An underpronator's arches or

ankles don't experience much motion as they cycle through the gait. An individual whose bone structure involves internal rotation at the hip, knee, or

ankle will be more likely to underpronate than one whose bone structure has external rotation or central alignment. Usually – but not always – those

who are bow-legged tend to underpronate.[citation needed] An individual who underpronates tends to wear down their running shoes on the lateral

(outside) side of the shoe towards the rear of the shoe in the heel area.[17]

Society and culture

Further information: Tradition of removing shoes in the home and houses of worship

Humans usually wear shoes or similar footwear for protection from hazards when walking outside. There are a number of contexts where it is

considered inappropriate to wear shoes. Some people consider it rude to wear shoes into a house and a Māori Marae should only be entered with

bare feet.

Foot fetishism is the most common form of sexual fetish.[18][19]

Other animals

Main article: Comparative foot morphology

A paw is the soft foot of a mammal, generally a quadruped, that has claws or nails (e.g., a cat or dog's paw). A hard foot is called a hoof. Depending

on style of locomotion, animals can be classified as plantigrade (sole walking), digitigrade (toe walking), or unguligrade (nail walking).

The metatarsals are the bones that make up the main part of the foot in humans, and part of the leg in large animals or paw in smaller animals. The

number of metatarsals are directly related to the mode of locomotion with many larger animals having their digits reduced to two (elk, cow, sheep) or

one (horse). The metatarsal bones of feet and paws are tightly grouped compared to, most notably, the human hand where the thumb metacarpal

diverges from the rest of the metacarpus.[20]

Metaphorical and cultural usage

The word "foot" is used to refer to a "...linear measure was in Old English (the exact length has varied over

time), this being considered the length of a man's foot; a unit of measure used widely and anciently. In this

sense the plural is often foot. The current inch and foot are implied from measurements in 12c." [1] The

word "foot" also has a musical meaning; a "...metrical foot (late Old English, translating Latin pes, Greek

pous in the same sense) is commonly taken to represent one rise and one fall of a foot: keeping time

according to some, dancing according to others."[1]

The word "foot" was used in Middle English to mean "a person" (c. 1200).[1] The expression "...to put one's

best foot foremost first recorded 1849 (Shakespeare has the better foot before, 1596)".[1] The expression to

Study of a pair of feet crossed,

"...put one's foot in (one's) mouth "say something stupid" was first used in 1942.[1] The expression "put

1847, by Margaret Louisa Herschel,

(one's) foot in something" meaning to "make a mess of it" was used in 1823.[1] daughter of John Herschel, from the

Royal Museums Greenwich

The word "footloose" was first used in the 1690s, meaning "free to move the feet, unshackled"; the more

"figurative sense of "free to act as one pleases" was first used in 1873.[1] Like "footloose", "flat-footed" at

first had its obvious literal meaning (in 1600, it meant "with flat feet") but by 1912 it meant "unprepared" (U.S. baseball slang).[1]

See also

Flat feet Sole (foot)

Foot binding Runner's toe, repetitive injury seen in runners

Foot fetishism Ball (anatomy)

Foot gymnastics Barefoot

Foot pressure Heel

Foot washing Squatting position

Gait analysis Comparison of orthotics

Pes cavus

References

1. ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Foot" . www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology 12. ^ Platzer 2004, pp. 270–72

Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 13. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 272

20 May 2017. 14. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 274

2. ^ a b c d Podiatry Channel, Anatomy of the foot and ankle 15. ^ TheFreeDictionary > Lisfranc's fracture Citing: Mosby's Medical

3. ^ Hawes MR, Sovak D (July 1994). "Quantitative morphology of the Dictionary, 8th edition. 2009

human foot in a North American population". Ergonomics. 37 (7): 1213– 16. ^ "Overpronation, Explained" . Runner's World. 21 September 2001.

26. doi:10.1080/00140139408964899 . PMID 8050406 . Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved

4. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 220 28 December 2012.

5. ^ Mareb-Hoehn 2007, pp. 244–45 17. ^ "Supination, Explained" . Runner's World. 21 September 2001.

6. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 256 Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved

7. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 258 28 December 2012.

8. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 260 18. ^ "Rex Ryan's Apparent Foot Fetish Not Necessarily Unhealthy" .

9. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 262 Abcnews.go.com. 2010-12-23. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

19. ^ "Archived copy" . Archived from the original on 2012-01-01.

10. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 264

Retrieved 2012-01-04.

11. ^ Platzer 2004, p. 268

20. ^ France 2008, p. 537

Bibliography

France, Diane L. (2008). Human and Nonhuman Bone Identification: A Color Atlas . CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6286-1.

Marieb, Elaine Nicpon; Hoehn, Katja (2007). Human anatomy & physiology . Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-321-37294-9.

Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

"Anatomy of the foot and ankle" . Podiatry Channel. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

External links

Foot at Curlie

Wikimedia Commons has

media related to Foot.

Look up foot in Wiktionary,

the free dictionary.

Wikiquote has quotations

related to: foot

V·T·E Human regional anatomy [show]

V·T·E Muscles of the hip and human leg [show]

Authority control GND: 4018967-3 · NARA: 10666106 · TA98: A01.1.00.040

Categories: Foot Human body Anatomy

This page was last edited on 7 August 2020, at 23:55 (UTC).

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Mobile view Developers Statistics Cookie statement

You might also like

- Advanced farriery knowledge: A study guide and AWCF theory course companionFrom EverandAdvanced farriery knowledge: A study guide and AWCF theory course companionNo ratings yet

- FootDocument1 pageFootsai calderNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of Voice: How to Enhance and Project Your Best VoiceFrom EverandAnatomy of Voice: How to Enhance and Project Your Best VoiceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Radius (Bone)Document8 pagesRadius (Bone)ranshNo ratings yet

- Anatomy & Physiology Terms Greek&Latin Roots Decoded! Vol. 6: Joint Systems, Planes & Directional TermsFrom EverandAnatomy & Physiology Terms Greek&Latin Roots Decoded! Vol. 6: Joint Systems, Planes & Directional TermsNo ratings yet

- Tibia: This Article Is About The Human Leg Bone. For Other Uses, SeeDocument11 pagesTibia: This Article Is About The Human Leg Bone. For Other Uses, SeeranshNo ratings yet

- Foot - WikipediaDocument8 pagesFoot - WikipediaThilini BadugeNo ratings yet

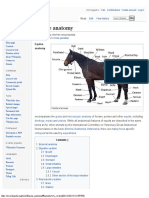

- Equine Anatomy WikipediaDocument13 pagesEquine Anatomy WikipediaJan Brylle Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- HandDocument1 pageHandsai calderNo ratings yet

- Full Download Ebook PDF Mastering Healthcare Terminology 5th Edition PDFDocument41 pagesFull Download Ebook PDF Mastering Healthcare Terminology 5th Edition PDFjohn.cerullo706100% (29)

- Dwnload Full Mastering Healthcare Terminology e Book Ebook PDFDocument51 pagesDwnload Full Mastering Healthcare Terminology e Book Ebook PDFkevin.larson517100% (31)

- This Article Is About The and Structure. For Legs in Humans, See - For Other Uses, See - "Legs" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, SeeDocument5 pagesThis Article Is About The and Structure. For Legs in Humans, See - For Other Uses, See - "Legs" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, SeeIhsan1991 YusoffNo ratings yet

- Femur PDFDocument9 pagesFemur PDFranshNo ratings yet

- Hip Bone: Hip Bone (Os Coxae, Innominate Bone, Pelvic Bone Coxal Bone) Is A LargeDocument9 pagesHip Bone: Hip Bone (Os Coxae, Innominate Bone, Pelvic Bone Coxal Bone) Is A LargeranshNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3.1: Luminang, John Chris Bsmls 1B Anaphy Nov. 18, 2021Document13 pagesAssignment 3.1: Luminang, John Chris Bsmls 1B Anaphy Nov. 18, 2021John Chris LuminangNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument5 pagesDocumentstella pangestikaNo ratings yet

- The Skeletal SystemDocument25 pagesThe Skeletal SystemEyda CartagenaNo ratings yet

- Mehak General Physiology Activity - Integumentary LabDocument7 pagesMehak General Physiology Activity - Integumentary LabMehak DhaliwalNo ratings yet

- FootDocument9 pagesFootToday NewsNo ratings yet

- The Skeletal SystemDocument6 pagesThe Skeletal Systemstar fireNo ratings yet

- GrossAnatLectNotes PDFDocument49 pagesGrossAnatLectNotes PDFSudhakar UtkNo ratings yet

- Mod 1.2 Musculoskeletal System UpdatedDocument26 pagesMod 1.2 Musculoskeletal System UpdatedNandhkishoreNo ratings yet

- The Skeletal SystemDocument24 pagesThe Skeletal SystemAlexa100% (1)

- Gross An at Lect NotesDocument50 pagesGross An at Lect NotesHongxia MaNo ratings yet

- Topic 4 The Foot and Ankle 16th JulyDocument39 pagesTopic 4 The Foot and Ankle 16th JulyTom Myhill-JonesNo ratings yet

- MANUAL OF LAB MSK WEEK One 2019Document8 pagesMANUAL OF LAB MSK WEEK One 2019Lisa OnoNo ratings yet

- The Skeletal SystemDocument24 pagesThe Skeletal SystemDaryhen GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Makalah Tulang Pada ManusiaDocument52 pagesMakalah Tulang Pada ManusiaIgoNo ratings yet

- 6.05 Leg - Neurovascular StructuresDocument3 pages6.05 Leg - Neurovascular StructuresChristian Clyde N. ApigoNo ratings yet

- Rad14 PrelimDocument9 pagesRad14 PrelimShan CabelaNo ratings yet

- Amano, Miles M. - Human AnaPhyW5-6Document4 pagesAmano, Miles M. - Human AnaPhyW5-6Khalil, Mikaela VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy: Connective TissueDocument1 pageAnatomy: Connective TissueSyimah UmarNo ratings yet

- The Skeletal SystemDocument25 pagesThe Skeletal SystemEyda CartagenaNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Chordates and Vertebrates: October 2017Document8 pagesDifference Between Chordates and Vertebrates: October 2017Aghnia ChoiNo ratings yet

- Ulnar Nerve: "Funny Bone" Redirects Here. For The Comedy-Drama Film, See - For The Comedy Club, SeeDocument8 pagesUlnar Nerve: "Funny Bone" Redirects Here. For The Comedy-Drama Film, See - For The Comedy Club, SeeranshNo ratings yet

- Human Anatomy Physiology Chapter 4 Osseous System NotesDocument17 pagesHuman Anatomy Physiology Chapter 4 Osseous System Notesmanku9163No ratings yet

- Lower Limb Lab SheetDocument3 pagesLower Limb Lab SheetKelly TrainorNo ratings yet

- Paired and Unpaired Bones of The SkullDocument6 pagesPaired and Unpaired Bones of The SkullYIKI ISAACNo ratings yet

- Sesamoid Bone: Jump ToDocument8 pagesSesamoid Bone: Jump ToBet Mustafa EltayepNo ratings yet

- Topic 6 Support Systems in AnimalsDocument8 pagesTopic 6 Support Systems in AnimalsOwenNo ratings yet

- Intro To Osteology (Oct 20, 2022)Document30 pagesIntro To Osteology (Oct 20, 2022)huzaifa arshadNo ratings yet

- Respiratory System - WikipediaDocument1 pageRespiratory System - WikipediaMatias Kristel AnnNo ratings yet

- Hindlimb - Anatomy & Physiology: Did You Know You Can or in Other Ways?Document75 pagesHindlimb - Anatomy & Physiology: Did You Know You Can or in Other Ways?Muhammad Asad ramzanNo ratings yet

- Plant Anatomy: Structural DivisionsDocument1 pagePlant Anatomy: Structural DivisionsSyimah UmarNo ratings yet

- Elzatona Anatomy 2023Document9 pagesElzatona Anatomy 2023mahmoud ezzeldeenNo ratings yet

- Midterms MedgloDocument13 pagesMidterms MedgloCorpuz, Jaylord L.No ratings yet

- Z3 Chordata PDFDocument7 pagesZ3 Chordata PDFPat Peralta DaizNo ratings yet

- Taxonomy DescDocument5 pagesTaxonomy DescSunder AbdusaidNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal PDFDocument79 pagesMusculoskeletal PDFDale DimaanoNo ratings yet

- 2.1 (A) - Support & Locomotion in Humans & AnimalsDocument59 pages2.1 (A) - Support & Locomotion in Humans & Animalsliefeng81100% (8)

- Pileus (Mycology) - WikipediaDocument2 pagesPileus (Mycology) - WikipediaLorenzo E.MNo ratings yet

- Guyon Canal - PhysiopediaDocument1 pageGuyon Canal - Physiopediaashfaqahammadm1mplNo ratings yet

- 7.2 Bone Markings - Anatomy & PhysiologyDocument1 page7.2 Bone Markings - Anatomy & PhysiologydonaldooiNo ratings yet

- MuscularDocument16 pagesMuscularAbigail ToriagaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy, Head and Neck, Levator Scapulae Muscles: April 2020Document10 pagesAnatomy, Head and Neck, Levator Scapulae Muscles: April 2020Milorad SpasićNo ratings yet

- Lab 1Document17 pagesLab 1NoyaNo ratings yet

- (11 F) Neuromusxcular CorrelationDocument3 pages(11 F) Neuromusxcular CorrelationJeffrey RamosNo ratings yet

- Anatomy Lower LimbDocument4 pagesAnatomy Lower Limbch yaqoobNo ratings yet

- Form Classification: ExamplesDocument3 pagesForm Classification: ExamplesAjay BharadvajNo ratings yet

- Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Leg Bones: February 2019Document8 pagesAnatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Leg Bones: February 2019Chess NutsNo ratings yet

- Indian Culture: MultiplicationDocument1 pageIndian Culture: Multiplicationsai calderNo ratings yet

- In Mathematics: List of Basic CalculationsDocument1 pageIn Mathematics: List of Basic Calculationssai calderNo ratings yet

- Music: Left May Refer ToDocument1 pageMusic: Left May Refer Tosai calderNo ratings yet

- Arts and Entertainment: AlbumsDocument1 pageArts and Entertainment: Albumssai calderNo ratings yet

- Places: Northern Ireland, UKDocument1 pagePlaces: Northern Ireland, UKsai calderNo ratings yet

- In Mathematics: MultiplicationDocument1 pageIn Mathematics: Multiplicationsai calderNo ratings yet

- Anthropology: Usage and TermsDocument1 pageAnthropology: Usage and Termssai calderNo ratings yet

- Evolution of The Glyph: Basic CalculationsDocument1 pageEvolution of The Glyph: Basic Calculationssai calderNo ratings yet

- ForwardDocument1 pageForwardsai calderNo ratings yet

- Shades and Variations: Indigofera TinctoriaDocument1 pageShades and Variations: Indigofera Tinctoriasai calderNo ratings yet

- RightsDocument1 pageRightssai calderNo ratings yet

- Green: Etymology and Linguistic DefinitionsDocument1 pageGreen: Etymology and Linguistic Definitionssai calderNo ratings yet

- Orange: Arts, Entertainment, and MediaDocument1 pageOrange: Arts, Entertainment, and Mediasai calderNo ratings yet

- Shades and Variations: This Article Is About The Color. For Other Uses, SeeDocument1 pageShades and Variations: This Article Is About The Color. For Other Uses, Seesai calderNo ratings yet

- BrownDocument1 pageBrownsai calderNo ratings yet

- Astral: Concepts of The Non-PhysicalDocument1 pageAstral: Concepts of The Non-Physicalsai calderNo ratings yet

- MentalDocument1 pageMentalsai calderNo ratings yet

- Acetylcholine ReceptorDocument1 pageAcetylcholine Receptorsai calderNo ratings yet

- Non-Compound EyesDocument1 pageNon-Compound Eyessai calderNo ratings yet

- HandDocument1 pageHandsai calderNo ratings yet

- Thought PDFDocument1 pageThought PDFsai calderNo ratings yet

- PhysicalDocument1 pagePhysicalsai calderNo ratings yet

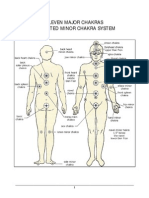

- Eleven Major ChakrasDocument6 pagesEleven Major Chakrasaynodecam100% (2)

- Anesthetic PDFDocument1 pageAnesthetic PDFsai calderNo ratings yet

- BehaviorDocument1 pageBehaviorsai calderNo ratings yet

- Subtle: Subtle May Refer ToDocument1 pageSubtle: Subtle May Refer Tosai calderNo ratings yet

- CausalityDocument1 pageCausalitysai calderNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic PDFDocument1 pageAnesthetic PDFsai calderNo ratings yet

- Employer BrandingDocument17 pagesEmployer BrandingSushri PadhiNo ratings yet

- Market AnalysisDocument143 pagesMarket AnalysisArivalagan VeluNo ratings yet

- ACS880 IGBT Supply Control Program: Firmware ManualDocument254 pagesACS880 IGBT Supply Control Program: Firmware ManualGopinath PadhiNo ratings yet

- Revivals in The Air RITA Chord ChartDocument1 pageRevivals in The Air RITA Chord ChartMatias GarciaNo ratings yet

- MicroStation VBA Grid ProgramDocument16 pagesMicroStation VBA Grid ProgramVũ Trường GiangNo ratings yet

- 01-14 STP RSTP ConfigurationDocument67 pages01-14 STP RSTP ConfigurationKiKi MaNo ratings yet

- Caning Should Not Be Allowed in Schools TodayDocument2 pagesCaning Should Not Be Allowed in Schools TodayHolyZikr100% (2)

- Line Follower Robot Using ArduinoDocument5 pagesLine Follower Robot Using Arduinochockalingam athilingam100% (1)

- Calibration Form: This Form Should Be Filled Out and Sent With Your ShipmentDocument1 pageCalibration Form: This Form Should Be Filled Out and Sent With Your ShipmentLanco SANo ratings yet

- Reflection of The Movie Informant - RevisedDocument3 pagesReflection of The Movie Informant - RevisedBhavika BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Madeleine Leininger Transcultural NursingDocument5 pagesMadeleine Leininger Transcultural Nursingteabagman100% (1)

- Renewal of ForgivenessDocument3 pagesRenewal of ForgivenessShoshannahNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Assessment of Fetal Well Being FileminimizerDocument40 pagesAntenatal Assessment of Fetal Well Being FileminimizerPranshu Prajyot 67No ratings yet

- 2023 HAC YemenDocument5 pages2023 HAC YemenRick AstleyNo ratings yet

- Bupa Statement To ABCDocument1 pageBupa Statement To ABCABC News OnlineNo ratings yet

- West Olympia Background Reports 14Document122 pagesWest Olympia Background Reports 14Hugo Yovera CalleNo ratings yet

- SCAM (Muet)Document6 pagesSCAM (Muet)Muhammad FahmiNo ratings yet

- Module 6:market Segmentation, Market Targeting, and Product PositioningDocument16 pagesModule 6:market Segmentation, Market Targeting, and Product Positioningjanel anne yvette sorianoNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts - Atkt Sem 1 (Internal Assessment)Document15 pagesLaw of Torts - Atkt Sem 1 (Internal Assessment)YASHI JAINNo ratings yet

- Scholarship ResumeDocument2 pagesScholarship Resumeapi-331459951No ratings yet

- Loan-Level Price Adjustment (LLPA) MatrixDocument8 pagesLoan-Level Price Adjustment (LLPA) MatrixLashon SpearsNo ratings yet

- Colin Campbell - Interview The Lady in WhiteDocument1 pageColin Campbell - Interview The Lady in WhiteMarcelo OlmedoNo ratings yet

- 7 P's of McDonaldsDocument11 pages7 P's of McDonaldsdd1684100% (4)

- ELT Catalog Secondary PDFDocument26 pagesELT Catalog Secondary PDFRafael Cruz IsidoroNo ratings yet

- GE1451 NotesDocument18 pagesGE1451 NotessathishNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Questions: Energy and MetabolismDocument75 pagesMultiple Choice Questions: Energy and MetabolismJing LiNo ratings yet

- NCM101Document485 pagesNCM101NeheLhie100% (3)

- Syllabus Mathematics (Honours and Regular) : Submitted ToDocument19 pagesSyllabus Mathematics (Honours and Regular) : Submitted ToDebasish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Pamrex - Manhole CoversDocument6 pagesPamrex - Manhole CoversZivadin LukicNo ratings yet

- AnatomyDocument4 pagesAnatomySureen PaduaNo ratings yet

- Boundless: Upgrade Your Brain, Optimize Your Body & Defy AgingFrom EverandBoundless: Upgrade Your Brain, Optimize Your Body & Defy AgingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (66)

- Relentless: From Good to Great to UnstoppableFrom EverandRelentless: From Good to Great to UnstoppableRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (783)

- Weight Lifting Is a Waste of Time: So Is Cardio, and There’s a Better Way to Have the Body You WantFrom EverandWeight Lifting Is a Waste of Time: So Is Cardio, and There’s a Better Way to Have the Body You WantRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (38)

- Peak: The New Science of Athletic Performance That is Revolutionizing SportsFrom EverandPeak: The New Science of Athletic Performance That is Revolutionizing SportsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (95)

- Muscle for Life: Get Lean, Strong, and Healthy at Any Age!From EverandMuscle for Life: Get Lean, Strong, and Healthy at Any Age!Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- Power of 10: The Once-A-Week Slow Motion Fitness RevolutionFrom EverandPower of 10: The Once-A-Week Slow Motion Fitness RevolutionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- Aging Backwards: Reverse the Aging Process and Look 10 Years Younger in 30 Minutes a DayFrom EverandAging Backwards: Reverse the Aging Process and Look 10 Years Younger in 30 Minutes a DayNo ratings yet

- Chair Yoga: Sit, Stretch, and Strengthen Your Way to a Happier, Healthier YouFrom EverandChair Yoga: Sit, Stretch, and Strengthen Your Way to a Happier, Healthier YouRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Functional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindFrom EverandFunctional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and MindRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Music For Healing: With Nature Sounds For Natural Healing Powers: Sounds Of Nature, Deep Sleep Music, Meditation, Relaxation, Healing MusicFrom EverandMusic For Healing: With Nature Sounds For Natural Healing Powers: Sounds Of Nature, Deep Sleep Music, Meditation, Relaxation, Healing MusicRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Strong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerFrom EverandStrong Is the New Beautiful: Embrace Your Natural Beauty, Eat Clean, and Harness Your PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Wall Pilates: Quick-and-Simple to Lose Weight and Stay Healthy. A 30-Day Journey with + 100 ExercisesFrom EverandWall Pilates: Quick-and-Simple to Lose Weight and Stay Healthy. A 30-Day Journey with + 100 ExercisesNo ratings yet

- Yamas & Niyamas: Exploring Yoga's Ethical PracticeFrom EverandYamas & Niyamas: Exploring Yoga's Ethical PracticeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- The Yogi Code: Seven Universal Laws of Infinite SuccessFrom EverandThe Yogi Code: Seven Universal Laws of Infinite SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- Whole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well to Minimal FootwearFrom EverandWhole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well to Minimal FootwearRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- SAS Training Manual: How to get fit enough to pass a special forces selection courseFrom EverandSAS Training Manual: How to get fit enough to pass a special forces selection courseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: Built for This: The Quiet Strength of PowerliftingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: Built for This: The Quiet Strength of PowerliftingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- Body by Science: A Research Based Program for Strength Training, Body building, and Complete Fitness in 12 Minutes a WeekFrom EverandBody by Science: A Research Based Program for Strength Training, Body building, and Complete Fitness in 12 Minutes a WeekRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (84)

- Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human PerformanceFrom EverandEndure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human PerformanceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (237)

- The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle: Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandThe Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle: Summary and AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- How To Walk Yourself Healthy And Happy: Discover the physical and mental benefits of regular walking.From EverandHow To Walk Yourself Healthy And Happy: Discover the physical and mental benefits of regular walking.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Not a Diet Book: Take Control. Gain Confidence. Change Your Life.From EverandNot a Diet Book: Take Control. Gain Confidence. Change Your Life.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (124)

- You: Breathing Easy: Meditation and Breathing Techniques to Relax, Refresh and RevitalizeFrom EverandYou: Breathing Easy: Meditation and Breathing Techniques to Relax, Refresh and RevitalizeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Body by Science: A Research Based Program to Get the Results You Want in 12 Minutes a WeekFrom EverandBody by Science: A Research Based Program to Get the Results You Want in 12 Minutes a WeekRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (38)