Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Understanding Private Higher Education in Saudi Arabia - Emergence Development and Perceptions

Uploaded by

emo_transOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding Private Higher Education in Saudi Arabia - Emergence Development and Perceptions

Uploaded by

emo_transCopyright:

Available Formats

!"#$%&'("#)"* ,%)-('$ .

)*/$% 0#12(')3" )" 4(1#) 5%(6)(

7 08$%*$"2$9 :$-$;3<8$"' ("# ,$%2$<')3"&

=1&&%( >(8?338

1hesis submitted to

Institute o Lducation

Uniersity o London

or the degree o Doctor o Philosophy

September, 2012

1

!"#$%&'$

1his thesis looks into the actors underlying the emergence, deelopment, and

understandings o priate higher education in Saudi Arabia rom three perspecties. 1he

irst perspectie is regional-historical, rom which I examine the rise and growths o the

priate sector rom a regional and historical point o iew. 1he second perspectie is

institutional, rom which I examine the perceptions o priate higher education among

dierent groups o stakeholders in comparison to its counterpart, the public sector,

through three dierent phases o priate higher education proision: 1,the entry point

2, the experience stage and 3, the exit to the job market. 1he third perspectie can be

perhaps understood as socio-political`, rom which I look at the relationship between

the priate sector and the wider political enironment, and also the use o the Lnglish

language in priate higher education proision: how it presents itsel as both a challenge

and beneit or arious stakeholders o it.

My analysis leads to a conclusion that the priate sector is a necessary complement to a

public one, which not only lacks the capacity but also is being challenged by many

ronts. 1he public sector was ound to all short in meeting quantitatie and qualitatie

demands or higher education. 1he sector o priate higher education in Saudi Arabia is

ound to proide more` opportunities to higher education, to hae dierent`

characteristics rom the public sector, leading it to be perceied as better` than the

public sector.

Oerall, this research is o a qualitatie nature. lor the regional-historical perspectie, I

use a wide range o literature and second-hand data. lor the institutional perspectie, I

make use o empirical data collected rom my ieldwork, which is also used or

discussions in the third dimension along with goernment policy documents.

Based on the oerall indings o this research, tentatie recommendations are made or

the uture deelopment o Saudi priate higher education.

2

!')*+,-./0.1.*$#

I would like to extend my sincere appreciation and gratitude to God and to all those

who encouraged and assisted me in this monumental task. Completion o this journey

would not hae been possible without God, my superisors, the prayers and support o

my amily and riends. 1hey were all incredibly supportie to me as I tackled this

endeaor. 1heir presence in my lie has enabled me to grow intellectually, emotionally,

and spiritually. 1hese ew words are not enough to express my deep appreciation.

I would like to thank my superisors Dr. Paul 1emple, Dr. Vincent Carpentier, and

Pro. Daid \atson or their academic support and adices.

Special thanks goes to pro Ley, a distinguished proessor at uniersity o Albany and

the director o PROPlL ,program or research on priate higher education,, who

despite o his busy schedule and obligations was generous enough with me. le has

gien me his ull attention, encouragement, suggestions, and guidance throughout my

research journey

I would like to express my special gratitude to my ather and mother who were

instrumental in my pursuit o this degree. 1hey hae set such a solid oundation in my

lie rom which I hae grown. I am also deeply grateul to my loely siblings, who

without their loe and understanding I wouldn`t hae accomplishes my educational

goals. I am oreer indebted or their loe and enduring support and patience.

I am also thankul to my cousins, uncles, aunts and riends. 1hey hae been a source o

blessing and support throughout my educational journey.

I would like to thank most sincerely, Saudi Arabia`s Ministry o ligher Lducation or

granting me a scholarship pursue my postgraduate degree in the UK.

linally, I am grateul to all participants who helped me make this study possible.

S

"#$%& '( )'*"&*"

#$+",#)" -

#).*'/%&01&2&*"+ 3

@A4B CD DAE!F04 4

@A4B CD B5G@04 4

@A4B CD 5,,0H:AI04 4

5#," 6 7

I.5,B0F J 8

AHBFC:!IBACH 8

RLSLARCl BACKGROUND 9

lIGlLR LDUCA1ION IN 1lL 201l CLN1UR\ 10

1lL GRO\1l Ol PRIVA1L lIGlLR LDUCA1ION \ORLD\IDL 11

PRIVA1L lIGlLR LDUCA1ION IN 1lL ARAB \ORLD 14

ORIGINS Ol SAUDI PRIVA1L lIGlLR LDUCA1ION 13

RLSLARCl QULS1IONS 17

PLRSONAL PLRSPLC1IVL 18

CONCLP1UAL lRAML\ORK 19

CON1RIBU1ION 1O KNO\LLDGL 21

LIMI1A1IONS 22

S1RUC1URL Ol 1lL 1lLSIS 23

I.5,B0F K 39

!H:0F4B5H:AHE ,FAL5B0 .AE.0F 0:!I5BACH 39

DLlINING PRIVA1L lIGlLR LDUCA1ION 23

lUNDING 28

O\NLRSlIP AND GOVLRNANCL 29

C8lLn1A1lCn 32

lunC1lCnS Anu 8CLLS: lllL8Ln1 L11L8 Anu C8L 33

GOVLRNANCL: PRIVA1L lIGlLR LDUCA1ION AND 1lL S1A1L 39

CONCLUSION 42

,5FB AA :;

I.5,B0F M :;

B.0 45!:A 5F5GA5H ICHB0NB :;

1lL ISLAMIC S1A1L 43

DLMOGRAPlICS 46

1lL SAUDI LCONOM\ 48

1lL LCONOM\ AND 1lL lIVL \LAR DLVLLOPMLN1 PLANS 30

1lL SAUDI LABOUR MARKL1 33

UNLMPLO\MLN1 AMONG SAUDI NA1IONALS 33

\OMLN`S PAR1ICIPA1ION IN 1lL LABOUR MARKL1 36

CONCLUSION 39

4

)<#5"&, : 4-

.AE.0F 0:!I5BACH AH 45!:A 5F5GA5 4-

7 0O0FE0HI09 :0L0@C,O0HB 5H: I.5@@0HE04 4-

ORIGINS Ol LDUCA1ION IN SAUDI ARABIA 61

S1RUC1URL Ol 1lL GLNLRAL LDUCA1ION S\S1LM 63

lIGlLR LDUCA1ION IN 1lL KINGDOM Ol SAUDI ARABIA 66

SUPPL\ AND DLMAND ClALLLNGLS IN lIGlLR LDUCA1ION: 1lL CON1RIBU1ION Ol 1lL PRIVA1L

SLC1OR 73

LNROLMLN1 IN 1lL SAUDI PRIVA1L SLC1OR 83

CCnCLuSlCn 87

)<#5"&, 9 78

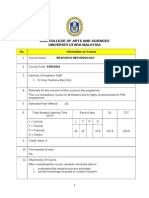

,&+&#,)< 2&"<'0'%'1= 78

RLSLARCl PARADIGM 89

LOCA1ING 1lL S1UD\,SLLLC1ING 1lL PAR1ICIPAN1S 91

SAMPLING 1LClNIQULS 93

lLC1 S1uu? 93

ML1lODS Ol DA1A COLLLC1ION 96

DA1A ANAL\SIS 103

VALIDI1\ AND RLLIABILI1\ 107

L1lICAL CONSIDLRA1IONS 110

CONCLUSION 112

5#," 666 --;

"<& 6*+"6">"6'*#% 062&*+6'* --;

)<#5"&, 4 --:

&*",= "' 5,6?#"& <61<&, &0>)#"6'* --:

ADMISSION RLQUIRLMLN1S 114

1lL LLI1LS OR 1lL UNDLRAClILVLRS 113

1lL NON-SAUDIS 121

SUBJLC1 ClOICLS 123

CCnCLuSlCn 132

)<#5"&, @ -;;

&A5&,6&*)&+ '( 5,6?#"& <61<&, &0>)#"6'* -;;

"&#)<6*1B %&#,*6*1B #*0 $&='*0 -;;

1LAClING AND LLARNING 133

CLASS SIZL AND SPLCIAL A11LN1ION` 137

ASSLSSMLN1: 1lL\ ARL NO1 ALL GOOD! 142

LX1RACURRICULAR AC1IVI1ILS 143

CONCLUSION 132

)<#5"&, 7 -9;

"<& &A6" 5<#+& -9;

C 5,6?#"& <61<&, &0>)#"6'* #*0 1,#0>#1LS' LMLCA8ILI1 -9;

PlCPL8 LuuCA1lCn Anu C8AuuA1LS LMLC?A8lLl1? 133

RLLLVANCL AND LINKAGL 1O 1lL LABOUR MARKL1 139

S

PRAC1ICAL LLARNING AND S1RUC1URLD \ORK LXPLRILNCL 160

S1RUC1URLD \ORK LXPLRILNCL 163

CARLLR CLN1RL AND S1UDLN1S` CONNLC1IONS 168

1lL PROlLSSIONALISM Ol 1lL GRADUA1LS 173

CONCLUSION 176

SUMMAR\ lOR PAR1 III 178

,5FB AL -73

5 GAEE0F ,AIB!F0 -73

I.5,B0F P -7;

0HE@A4. 54 5 O0:A!O CD AH4BF!IBACH -7;

LNGLISl AND 1lL RLGIONAL CON1LX1 183

1lL LN1R\ PlASL : S1UDLN1S` ClOICL AND ACCLSS 186

1lL LXPLRILNCL PlASL: 1LAClING AND LLARNING 190

1lL lACUL1\ RLCRUI1MLN1 ClALLLNGL 193

1lL LABOUR MARKL1 ClALLLNGL 200

CONCLUSION 204

)<#5"&, -D 3D9

5,6?#"& <61<&, &0>)#"6'* #*0 "<& +"#"& 3D9

1lL RLLUC1AN1 S1A1L 207

1lL CON1ROLLING S1A1L: LICLNSING AND RLGULA1IONS 211

1lL S1A1L`S lINANCIAL SUPPOR1 1O PRIVA1L lIGlLR LDUCA1ION 221

IN1LRNAL SClOLARSlIPS 224

CONCLUSION 228

)<#5"&, -- 338

)'*)%>06*1 "<'>1<"+ 338

5,,0H:AI04 34D

F0D0F0HI04 37D

6

@)&' 3Q D)*1%$&

igvre 1: avai Povtatiov Percevtage. b, Cevaer ava .ge Crov:200 "#

!"#$%& () *+$,-."/0 123.&4 /5 .6& 7"0#+/4 /5 1-$+" 8%-9"- $%

@)&' 3Q B(6;$&

1abte 1: Per.ectire. for vvaer.tavaivg rirate igber avcatiov &#

1abte 2: avai ava ^ovavai !or/force Di.tribvtiov-Pvbtic ava Prirate ector. %'

1abte : Mavorer trvctvre b, Occvatiov ava ^atiovatit, %"

1abte 1: avai igber avcatiov v.titvtiov. 112012 $(

1abte :: igber avcatiov vrotvevt ^vvber.: 1200: ##

1abte : Pvbtic igber avcatiov .b.ortiov Caacit, #)

1abte : vt,Devava: ectea Ca )*

1abte : avai Prirate igber avcatiov v.titvtiov. 20002012 )&

1abte : tvaevt.` vrotvevt iv igber avcatiov ,.tev )"

1abte 10 : vrotvevt iv Prirate igber avcatiov v.titvtiov. )$

1abte 11: vrottea .tvaevt. tva,ivg .broaa 200 )#

1abte 12: Particiavt. b, ta/ebotaer Categor, ("

1abte 1: vvvar, of Re.earcb Metboa.,Pvro.e (#

@)&' 3Q 5<<$"#)2$&

.evai ;1): Partiat ti.t of ^er |virer.itie. ava Cottege. iv tbe Cvtf &$+

.evai; 2): ^er |virer.itie. ava 1beir .ffitiatiov. &$'

.evai ;): vforvea Cov.evt orv &#%

.evai ;1): Ma;or. Offerea b, Prirate igber avcatiov v.titvtiov. &#$

.evai ; :): Proortiovat Di.tribvtiov of .tt igber avcatiov Craavate. b, Ma;or. &#)

.evai ;): Percevtage of Ma;or. offerea b, Prirate igber avcatiov v.titvtiov. &#(

7

:$2;(%(')3" ("# R3%# @$"*'/

I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted either in the same or dierent

orm, to this or any other Uniersity or a degree. I also declare that, except where

explicit attribution is made, the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. 1he

word length o this thesis ,inclusie o table and igures, and exclusie o bibliography

and appendices, is: 81,91 \ords.

8

2!34 5

9

I/(<'$% J

A"'%3#12')3"

In this opening chapter o my thesis, I shall begin with a brie historical reiew o the

rise, the deelopment and the growth o the priate higher education sector. I shall

then discuss the rise o priate higher education in the Middle Last, and in particular,

Saudi Arabia, in order to amiliarise my readers with the regional context o priate

higher education. 1hen I shall present my research questions in this regard and also the

conceptual ramework and the structure o this thesis. loweer, at this point, allow me

to briely elaborate on the immediate background o this research.

F$&$(%2/ G(2S*%31"#

1hough priate higher education has been common worldwide or many decades, it was

only in 1998 that the irst such institutions were permitted to open in the Kingdom o

Saudi Arabia. Also, there are ew works on Saudi priate higher education. 1hereore,

this thesis makes its unique contribution through an examination o the actors that

hae contributed to the emergence and the deelopment o the priate sector. In doing

so, this study also inestigates the extent to which this sector is distinct rom its

counterpart, the public sector.

1he public sector was ound to all short in meeting quantitatie and qualitatie

demands or higher education. 1he demand on higher education has been beyond the

capacity o the public sector. Stakeholders perceie dierences between public and

priate higher education. 1he priate sector is seen to oer higher quality education in

terms o teaching, learning, and extracurricular actiities, etc. 1he priate sector is also

seen to improe graduates` employability because o the eatures aboe as well as its

emphasis on practical class assignments and internships which link graduates more

directly with the labour market. Although still only a small part o total enrolment, the

priate sector also proides access to some students who cannot gain admission to the

public uniersities. 1he Goernment is ound to hae a major role on the emergence o

the priate sector - no priate institution existed beore its ormal initation to the

1u

sector. 1he Goernment, howeer, has demonstrated an ambialent attitude towards

priate higher education-in terms o planning, regulation, recognition and inancial

support.

lor the purpose o this research, I adopted a qualitatie research design or this

exploratory study. 1he perceptions o a broad range o stakeholders--students,

graduates, aculty and administrators, employers, goernment oicials--were gathered

through semi-structured interiews and thematically analysed. Secondary research

sources included releant literature on higher education and goernment policy

documents.

.)*/$% 0#12(')3" )" '/$ KT'/ I$"'1%U

A wider research background or this research is the rise o priate higher education in

the global context. Oer the past ew decades, higher education throughout the world

has undergone signiicant changes regarding its role and structure ,1eichler, 1988, 2006,.

Until the early twentieth century, higher education was limited to a ew uniersities

outside Lurope, North America, and the colonies o Great Britain ,Rohstock, 2011,.

ligher education was considered a public space|s| or ree inquiry and the

deelopment o minds`, an exemplary locus or deliberation, communication,

interaction, and searching or truth or inter-subjectie consensus` ,lreid et al., 200,

p.594,. \hile these remain important unctions or higher education other economic

and social demands became important ocuses or it. 1hus, higher education was no

longer limited to the purpose o training or the elite.

1he massiication` o higher education systems started to take place in the 1930s in the

USA, and shortly ater the Second \orld \ar in the UK, the USSR, and other

Luropean countries. During this period, the economic and social roles o goernments

changed and as a result, higher education expansion was seen as a signiicant means to

ulil wider political, social, and economic objecties o modern goernments ,Robbins,

1963, \ittrock & \agner, 1996,. Policymakers were chiely concerned with the human

capital requirements in their planning or higher education. Modern neoclassic

economists like Mincer ,1993, and Becker,1964, argued that inestment in human

11

capital through education and training would lead to economic prosperity or both

indiiduals and businesses. It was argued that in order to increase the store o human

capital within a nation, higher education should be aailable tuition ree to all because

their knowledge and skills would be o social beneit ,Sadlak,2000,. Similarly,

goernments o deeloped and deeloping countries towards the end o the twentieth

century became more concerned about improing the store o human resources,

especially with the adent o globalisation and the knowledge economy ,Blondal et al.,

2002,. Indiiduals also became increasingly keen to pursue higher education or its

obsered positie impact on their employability, personal income, and social status

,Mincer, 1993,. 1hus, higher education and goernments hae been acing signiicant

inancial and academic challenges because o this expansion o higher

education,1eixeira, 2009,. As the world globalises, economic competitieness oten

depends on the extent to which a country can participate in the knowledge-based

economy ,Blondal et al., 2002,.

B/$ E%3V'/ 3Q ,%)-('$ .)*/$% 0#12(')3" R3%;#V)#$

\hile many goernments in adanced economies were adopting a modern welare state

model in which equality and distribution o wealth was a key principle, unding the

continuous expansion in higher education proed challenging ,Barr, 2004,. 1he

increasing demand or higher education proed to be beyond the inancial capacity o

many goernments, especially with the crisis o the welare state rom the 1980s

onwards ,Barr, 2004,. Since then, there has been a need or greater eiciency in the

allocation and distribution o public resources ,Cae et al., 1990,. Managerial alues and

conducts were promoted in public institutions, including higher education ,Amaral et

al., 2003,. It was no longer easible or goernments to be ully responsible or the rising

cost o higher education ,Neae & Van Vught, 1994,. 1his was in line with macro-leel

iscal policies designed to restrain goernment expenditure and to increase priate

inolement in the proision o social serices, a process o liberalisation ,Middleton,

1996, Ball, 200,.

As goernments began to reduce their direct control oer higher education, the system

became more diersiied and public institutions were no longer the only orm o higher

education proided ,1eichler, 2006,. Priatisation was one policy introduced to reduce

12

dependence upon goernment unding. Recognising and accrediting priately managed

higher education institutions has been an increasingly popular practice. One reason or

this has been to enable such institutions to meet the increasing demand o higher

education, which the public sector inds diicult to manage alone. Research by the

Programme or Research on Priate higher education ,PROPlL, ound that up to 31

o the global share o higher education is now run priately ,Ley, 2011,, in the sense

o its not being a state institution. loweer, ideas such as priate` or public` are now

rather complex, which will be discussed at length later in this thesis.

Unlike in Saudi Arabia, the priate proision o higher education is not new around the

world. In the USA, Latin America and Japan, it has existed or oer a century. loweer,

since the late 1980s priate higher education has expanded and spread to most countries

,Ley, 2010b,. 1he rapid growth o priate higher education has been particularly

signiicant since the last decade o the twentieth century ,Altbach, 2005,2009, Ley,

2002, 2005,. In the early twenty-irst century, there hae been increases in the

aailability o priate higher education in post-socialist Central and Lastern Luropean

countries ,Altbach, 2005, Ley, 200,.

listorically, growth in this sector ranged rom the old and traditional-aimed at the

elite and religious groups-to educational institutions which had a wider appeal.

According to the extant literature, there are ery ew countries which hae a long history

o priate higher education. One notable exception is the USA, which depended on the

priate sector until the late nineteenth century ,Chronister, 1980, 1helin, 2011,. It is

interesting to note that although the USA is considered to hae the largest number o

priate higher education institutions, student enrolment in these institutions accounts

or less than 20 o the total enrolment ,Altbach, 1999, 2005,. loweer, there is a

notable increase in the emergence o priate proit-making institutions such as Phoenix

and Strayer in the USA in recent decades ,Kinser & Ley, 2006,. Similarly, a number o

Last Asian countries, including Japan, South Korea, 1aiwan, Indonesia, and the

Philippines, hae long-established priate higher education , with up to 80 o the

students in these countries pursuing courses in them ,Altbach, 1999,.

1here are some countries in which there is not a long-standing tradition o priate

higher education. \et in these countries, when priate education was irstly introduced,

it was oten considered to be growing too ast` ,Altbach, 1999, 2005, Ley, 1992, 2002,

2006b,. lor example, there are Asian countries such as China and Vietnam which do

1S

not hae an established tradition o priate higher education institutions, but they are

currently witnessing substantial growth in both the supply o and the demand or public

higher education. China now has around 1,200 such institutions ,Altbach et al.,2009,

Gupta, 2008,. In India, the sector is growing extremely rapidly, with one o the largest

number o priate higher education institutions in the world ,Gupta, 2008, Ley, 2008,.

Altbach et al. ,2009, and Ley ,2005,200, explain that the priate sector has been the

astest growing segment o higher education in many Central and Lastern Luropean

countries since the 1990s and the all o Soiet Communism. But the percentage o

enrolment in priate higher education aries greatly between countries o the old Soiet

bloc ,Slantchea & Ley, 200,. Ley indicates that this expansion has been unplanned

and unregulated ,Ley,2002,. Interestingly, countries such as Poland hae deeloped

priate higher education sectors which account or up to 30 o the entire higher

education sector ,Ley, 2003,. In other countries, such as Russia and Bulgaria, the

priate sector accounts or roughly 10 o higher education, while in Albania and

Croatia the priate sector is extremely minimal ,Ley, 2003,. Although priate higher

education institutions are the astest growing segment o higher education in Arica, the

enrolment still accounts or a small share o the total enrolment ,Varghese, 2004,. South

Arica is among the Arican countries in which the priate sector is growing ery rapidly

and, interestingly, most o these are proit-making institutions ,Mabizela, 200, Kinser

& Ley, 2006,.

Latin America presents an interesting case. Although there is a long tradition o priate

higher education, at the same time the region is experiencing extremely ast rates o

growth. Latin American countries hae been experiencing a large growth in the priate

sector since the 1960s ,Ley, 1986a,, and in most o them the percentage o student

enrolment in priate institutions accounts or about a third o the total enrolment in

higher education ,Kinser et al., 2010,. In places like Brazil and Chile, the priate sector

accounts or hal the total enrolment ,Altbach, 1999, Ley, 2005,.

Research shows that in other parts o the world, growth in the priate sector is slower.

\estern Lurope remains cautious about the emergence o the priate sector. 1here its

contribution to higher education is limited and is the lowest or any region in the world.

In this geographical area 90 o the enrolment is in the public sector ,Altbach, 1999,

2005,. 1he priate sector is still small in major Luropean countries like lrance, the UK,

and Germany. Research also shows that there are countries such as Japan and Poland

14

which are experiencing a decline in priate higher education growth ,Ley, 2010a, due

to demographic trends rather than anything directly related to the perormance o

uniersities. Ley explains that this is a result o social and political actors, such as

declining population and urther control rom the goernment. Although Portugal was

one o the irst countries in \estern Lurope which allowed priate higher education,

there is now a decline in the number o students enrolled in those institutions ,Amaral

& 1eixeira ,2000, 1eixeira, 2006,.

Lxploring the growth o priate higher education institutions in an international context

allows or better understanding o dierences in the deelopment o the priate sector

throughout the world. 1he preiously cited research makes clear that priate higher

education institutions hae begun to step into the market o higher education in many

parts o the world. lurther, when we look at the growth we ind that there is signiicant

ariation across countries, as some exhibit tremendous growth while other countries

experience moderate or mild growth. \e can see how deeloping countries are

increasingly dependent upon priate institutions, whereas the deeloped countries are

still primarily dependent upon their strong public education sectors.

Coman ,2003, and Ley ,2009, hae traced the recent growth o priate higher

education institutions in the Gul Cooperation Council States ,GCC, o Saudi Arabia,

Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Lmirates, and Oman. In Saudi Arabia a second

attempt has recently been made to establish a priate higher education sector. 1he irst

attempt in 196 ailed to take root and inoled just one institution, which was

transormed into a publicly unded and goerned uniersity. 1he ollowing section

seres as a brie introduction to the deelopment o priate higher education in the

Arab region.

,%)-('$ .)*/$% 0#12(')3" )" '/$ 5%(6 R3%;#

Priate uniersities in the Middle Last were irst established in the late nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries. 1he Uniersity o Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth, ounded in 185,

was a lrench medical college located in Beirut and. 1he American Uniersity o Beirut

was established in 1866 ,Ghabra & Arnold, 200,lerrera,2006,. 1he American

Uniersity in Cairo was ounded in 1919 by American missionaries and was an Lnglish-

language school. It was licensed in the State o New \ork with its Board o 1rustees

1S

and administratie oices in New \ork City ,Ghabra & Arnold, 200,. 1hese early

institutions, with \estern curricula, administration, and accreditation, sered as models

or the wider Arab world. Bertelsen ,2009, obseres that these institutions

demonstrated:

Successul goernance, quality assurance and unding can achiee academic

success and recognition, as well as contributing signiicantly to human and

other deelopment in the host societies and the wider Middle Last. ,p. 2,.

1hese institutions all eentually aced political pressures, backlash against the \est,

nationalist pride and resentment, threats o nationalisation, and in the case o Lebanon,

iolence. \hile struggling to maintain their autonomy, the two American uniersities

were required to hire eer greater numbers o Lgyptian and Lebanese aculty members.

1he real beginnings o widespread priate higher education in the Middle Last dates

rom the 1980s. Priate uniersities were ounded in Jordan, Lgypt, Sudan, and the

UAL with arying degrees o quality, success, and educational approaches. By the early

1990s, in the Gul States the pace rapidly accelerated. \illoughby ,2008, accurately

characterises this phenomenon as an explosion o new higher education institutions in

the small GCC countries` ,p. 25,. Between 1992 and 200, 54 new priate uniersities

with \estern ,or Asian, ailiations were established in the Gul countries. 1he totals

or each country were: Bahrain-4, Kuwait-5, Oman-19, Qatar-4, the UAL-21

,\illoughby,2008,. A complete list o these institutions is presented in Appendix 1.

Noticeably, Saudi Arabia, the largest and wealthiest nation in the Gul, had shown the

least openness to this trend.

C%)*)"& 3Q 4(1#) ,%)-('$ .)*/$% 0#12(')3"

1he irst priate uniersity in Saudi was opened in 196-King Abdul Aziz Uniersity

,KAAU,. It was located in the city o Jeddah, and unctioned as a priate higher

education institution or our years beore it became a public uniersity. 1he KAAU

originated rom an idea in an article in Al-Madina Saudi newspapers in 1964 by its chie

editor Mohamed Ali laiz ,Batary,2005,. 1hough not eeryone welcomed the idea, it

was supported by seeral businessmen. At that time, the country`s sole uniersity was

King Saud Uniersity in Riyadh, a public institution. Prominent citizens in the coastal

16

city o Jeddah argued that the country`s only uniersity was not accessible or people in

other parts o the country. 1he Goernment, howeer, contested the establishment o a

priate uniersity in Jeddah. A prominent businessman donated land and premises to

be the campus o the new institution. 1he enture took o with the enthusiasm o its

local supporters and the dedication o experts rom Arab and \estern countries

,Batary,2005,.

Lentually, success brought its own problems. 1uition was ree, and income rom

donations and real-estate trusts were not suicient to sustain the enture. 1he

increasing demands in access to the newly born uniersity led to serious inancial

diiculties. 1he uniersity managed to gain minimum support rom the Goernment,

but the support was not suicient to alleiate the problem. In 191, the Uniersity

Board asked the Goernment to take it oer. 1he uniersity thus became a public higher

education institution under the same name-King Abdul Aziz Uniersity ,Batary,

2005,.

1he ailure o KAAU as a priate uniersity and its takeoer by the Goernment was to

hae a long-lasting negatie impact on the uture deelopment o priate higher

education in the Kingdom which was to persist or decades. 1he consequences o that

ailure will be urther discussed in details in Chapter 10. Ater 191, priate higher

education ceased to exist in the Kingdom and remained dormant. 1he idea was reied

in the Goernment`s Sixth Deelopment Plan o 1995-2000. Studies were conducted,

and the Council o Ministers approed the re-establishment o priate higher education

in 1998. 1his was only the second time the Goernment authorised the deelopment o

priate higher education in the kingdom o Saudi Arabia ,KSA,, and it is thus

considered a ery new phenomenon. 1he irst institutions opened as recently as 2000.

\hile there are now 18 priate colleges and 9 uniersities, this whole sector is still

eeling its way`. lor those Saudi educators inoled in the ield, priate higher

education remains ery much an experiment.

17

F$&$(%2/ W1$&')3"&

In this thesis, I explore the reason behind the rise and deelopment o priate higher

education in Saudi Arabia. lere are my main research questions:

1, \hat are the contributing actors behind the emergence and deelopment o priate

higher education in the Saudi Arabia

2, 1o what extent is the Saudi priate higher education sector perceied to be distinct

rom the public sector

3, \hat are the wider implications o priate higher education or the higher

education system and the country in general

A qualitatie research design was employed to address these research questions. Data

are gathered rom two major channels: irst, interiews with oer a hundred

stakeholders, and second,-goernment policy documents and some other texts such as

websites. I also analyse secondary literature to proide background and context or the

research. 1hese second-hand data are also used to complement and,or support the data

rom the interiews.

1he unction o priate higher education in one country cannot be deduced rom

experiences in other national contexts. loweer, priate higher education in one

country may relect global trends, while haing some distinctie elements o its own.

1his study hopes to ascertain to what extent this is possible.

18

,$%&3"(; ,$%&<$2')-$

Apart rom my academic studies or this PhD, this research is much inspired by my

personal educational experience and also working experience in Saudi Arabia and

beyond.

I receied my B.A. degree in Business Administration at King Abdul-Aziz Uniersity

,KAAU,, a public uniersity in Saudi Arabia but which, at one time, had been the irst

priate uniersity in Saudi Arabia. I then obtained an M.A. degree in Inormation

Management at Marymount, a priate college in \ashington D.C. Subsequently, I

completed an M.A. degree in Assistie 1echnology ,technology or the disabled, at

George Mason, a public uniersity in Virginia. 1hus, in my own academic path I hae

experienced both public and priate higher education institutions in two ery dierent

countries. 1hese experiences heightened my awareness o dierences between public

and priate higher education.

In addition, priate education has also been part o my amily history. My amily hae

been educational pioneers in Saudi Arabia with my grandather, Abdul-Raou Jamjoom

establishing with colleagues, Al-lalah school, the irst priate school or boys in Jeddah

1905. In the 1960s, an uncle o mine was a co-ounder o the country`s irst priate

uniersity. \hen I returned rom the US to Saudi Arabia at the end o 2006, I began

working at a priate college in Jeddah which opened in 2000 marking the new beginning

o priate higher education in Saudi Arabia. Initially, I helped instructors to deelop

practical elements in their courses linked to speciic market needs. lor example, I tried

to link up Inormation 1echnology course materials to the banking sector based on

discussions with bank oicials. My work was made possible because the college was a

new institution in a new ield o education, one which was especially ocused on linking

theory to practical class assignments related to the labour market. 1his was itally

important as the public uniersities had not managed to proide employers with

suicient numbers o adequately trained graduates.

19

My personal working experience added some new perspecties to my understanding o

the priate sector in Saudi Arabia. In 200, I became Vice Dean o Student Aairs at

this priate college. By that time, it had 400 emale students and 00-800 male students

attending on two separate campuses. My position included oerseeing enrolments and

registration, extracurricular actiities, the student union as well as the career and

counselling centres. 1hese arious areas o college operations and my daily contact with

students gae me new insight into the special qualities ,and problems, o priate higher

education and its contrast with the public sector. lor example, I initially did not

consider extracurricular actiities to be o particular signiicance compared to academic

courses but I came to see the importance these had or students, especially in a closed,

restrictie society like Saudi Arabia. Similarly, the importance o internships, student

union actiities and the career centre were also a reelation to me. 1he impact o these

aspects o college lie is iidly expressed by the student stakeholders themseles in

Chapter o this study.

\hen I let or the US or my graduate work, priate higher education was just

beginning in the Saudi Arabia. \hen I returned and took the position o Vice Dean at a

priate college, I became keenly aware o the diicult transitional state o a new

institution oering a new kind o education. Many people, particularly the parents o

prospectie or newly enrolling students, were doubtul and hesitant about this new

college. Did the goernment really recognize it Did it hae the proper licenses \as

it accredited \ould it last \hat would sustain it \as it really better than public

higher education which in Saudi Arabia is tuition-ree and comes with a paid stipend

1hese were questions I had to answer on a daily basis and with serious questioning on

my own part. It was these kinds o questions that led me to the research questions o

the present study. By exploring explore stakeholders` perceptions o Saudi priate

higher education it has been possible to proide answers to a number o questions.

I3"2$<'1(; D%(8$V3%S

lor the purpose o this research, there is perhaps no single theory which can it

perectly as a research ramework. 1hereore, I deelop my own conceptual ramework

to conduct this proposed multi-aceted analysis o priate higher education in Saudi

2u

Arabia. I intend to explore the rise, deelopment, and perceptions o priate higher

education rom three perspecties: regional-historical, institutional, and socio-political.

Allow me to elaborate a little more on these three perspecties. lor the irst perspectie,

I place a discussion o the rise and deelopment o priate higher education in a

regional context, and look or releant inormation in history which will shed some light

on the birth and growth o the priate sector. 1his is perhaps among the most

commonly used approaches. loweer, I do not intend to inestigate certain

understudied historical eents or to clariy some misunderstandings about the local

educational history. Instead, I intend only to conduct a regional-historical reiew which

would proide enough background inormation or my examinations in another two

analyses: Parts III and IV o this thesis.

\ith regard to the second perspectie, institutional, I do not plan to inestigate the

goernance or daily management practices o priate institutions. Rather, I only wish to

place my discussions and analysis in an institutional setting. lor this part, I look into, in

particular, the perceptions o the priate sector among dierent stakeholders o higher

education-students, aculty members, administrators, regulators, and employers, in

terms o the three phases o higher education: Lntry to the system, Lxperience within

the system, and exit to a job market. 1his, I beliee, is a rather straightorward way to

organise the themes and topics which emerged rom my ield.

lor the third perspectie, I must be cautious in pointing out that my analysis bears a

ery small ambition. I do not propose to inestigate local politics, international

relationship, or social changes in the Middle Last, as one might read in a conentional

political or social study. Rather, my scope o analysis is much narrower than the

conentional Middle Last studies. I choose two issues which I ind most releant to the

inquiry o this thesis: the use o the Lnglish language in the priate sector, and also the

changing relationship between the priate sector and the Saudi Goernment. 1hese two

issues, I beliee, can shed some interesting light on the past growth and also the uture

deelopment o priate higher education in a Middle Last country such as Saudi Arabia.

1he use o the Lnglish language, or instance, brings both beneits and challenges to the

participants o higher education and also others who iew this issue rom a non-

educational angle. 1he changing relationship between the priate sector and the Central

Goernment seres to remind us that there is no single uniersal way to understand

21

priate higher education, eery country has its particular socio-political context, without

which one cannot possibly understand what really happened, and why things happened

in the ways they did.

In the light o this conceptual ramework, I now moe on to present the structure o

this thesis.

I3"'%)61')3" '3 X"3V;$#*$

1his research contributes to two study areas: irst, to higher education studies, in

particular studies o the priate sector, second, to regional studies o the Middle Last

and, in particular, Saudi Arabia.

lor the ormer, studies o the priate sector only began to attract wider attentions in the

1990s, and in general, literature on priate higher education is still ery limited. It is

more so, on the regional leel o the Middle Last. A reason or this scarcity is that the

system is relatiely new to the region compared to other parts o the world. Also, the

research area is less actie in this region. Lxploring the situation o priate higher

education in the KSA will add a ield to the global landscape, proiding comparisons

and contrast with the situation in other countries.

lor the latter, the Middle Last, although not a new topic, has been intensiely studied

rom social, cultural, and political perspecties. \ith regard to the case o Saudi Arabia,

most o the international publications are around its modern history, political economy,

oreign policy, and cultural identities. lew, i any, study the country rom the

perspectie o higher education. 1hereore, this research brings in a new angle to studies

o the region. By looking into the role o priate higher education, one can better

understand how a modern Middle Last country such as Saudi Arabia is coping with the

changes and challenges which come with the global economy.

1he present study is stimulated by the work o Daniel Ley o \ale Uniersity. Ley has

been a prominent in arguing that the priate ligher Lducation system has not been a

static entity but instead has changed and eoled oer many years in response to social,

economic and political change ,1986a, 2006a, 200,. Ley`s work, amongst others, has

asserted that with recent expansion o the priate sector, it has now become a major

presence within ligher Lducation generally and thereore it deseres sustained critical

22

inestigation. 1he present study is a contribution towards this aim that Ley adocates,

ocussing upon deelopments within the Saudi Arabian l.L. Sector which up to now

has not been studied in much detail. 1he intention o the present study is to make a

contribution to the international understanding o the growth and character o priate

l.L. Roger Geiger o Pennsylania state Uniersity has been another key inluence or

the present study through his work on typologies o the purpose o the priate higher

education system. lis work has drawn attention to the inherent diersity that exists

within this sector, something that is traced in some detail through this study in relation

to Saudi Arabia

@)8)'(')3"&

One o the major limitations o this study is related to its data sample. I managed to

collect data or my empirical work rom one city only, where higher education

institutions are most concentrated. 1his will ineitably raise the issue o the

generalisabitity o my indings. 1his also applies to the act that all student interiewees

at the higher education institutions inoled in this study specialise in business-related

subjects. Another limitation is related to the access to goernment personnel and policy

documents, I managed to interiew only a relatiely small number o goernment

oicials and gain access to a number o goernment documents on priate higher

education. 1his limits the scope o my research in particular rom the socio-political

perspectie.

2S

4'%12'1%$ 3Q '/$ '/$&)&

1his study is organised into our parts. Part I, including this chapter, seres as a

background discussion or later sections. Part II, including Chapters 2 and 3, looks into

the rise and deelopment o priate higher education in Saudi Arabia rom a regional-

historical perspectie. Part III, including Chapters 6, , and 8, adopts an institutional

perspectie, looking into the three phases o higher education: Lntry, Lxperience, and

Lxit. Part IV, including Chapters 9 and 10, takes up a socio-political perspectie, by

looking at the use o the Lnglish language in the priate sector, and also the changing

relationship between the priate sector and the Saudi Goernment.

lor the plan with each indiidual chapter, Chapter 2 discusses the complexity inoled

in deining priate higher education. It presents concepts used in the literature or

analysing priate higher education.

Chapter 3 proides a brie history o the country, its goernance, and its demographics.

1he Saudi economy is analysed with regard to national deelopment plans, the labour

market, unemployment among Saudi Arabian nationals, and the participation o women

in the workorce.

Chapter 4 sureys the deelopment o the Saudi Arabian education system, particularly

public higher education. Chapter 4 analyses the newly emerging priate higher education

sector. 1his is seen in the regional context o the Gul States. Lnrolment trends and

supply,demand challenges are examined.

lollowing these background chapters, Chapter 5 outlines the methodology o the study,

discussing in detail the qualitatie interpretie research approach selected. Methods used

to gather and analyse the data deried rom stakeholders` perceptions o Saudi priate

higher education are described.

Chapters 6 and present an in-depth look at a wide ariety o stakeholders` perceptions

o that sector in relation to admission requirements, subjects` choices, teaching, learning

and extracurricular actiities. Chapter 8 explores the relationship between priate higher

education and the Saudi labour market. Literature on graduates` employability and the

labour market is reiewed. 1he skill leels o graduates are considered and the alue o

practical class assignments and internships as links to the labour market are presented

through the perceptions o stakeholders.

24

Chapter 9 coers stakeholders` perceptions on the use o the Lnglish language as a

medium o instruction in priate higher education institutions, and the implication it has

or students` choice o institutions ,public or priate,, teaching, learning, and graduates`

employability.

Chapter 10 examines the relationship between Saudi priate higher education and the

Goernment. Goernment policies, regulations, and inancial support, as well as quality

assurance mechanisms, are analysed as a complement to stakeholders` perceptions.

1he Conclusion will address the oerall indings o the research, and explore some

bigger issues that emerge rom my discussion in this thesis. 1he thesis will end with

some recommendations or the uture deelopment o Saudi priate higher education.

2S

I/(<'$% K

!"#$%&'("#)"* ,%)-('$ .)*/$% 0#12(')3"

A"'%3#12')3"

1his chapter attempts to discuss priate higher education in Saudi Arabia with reerence

to some concepts and typologies used in priate higher education studies. I irst look

into the diiculty o identiying priate higher education. 1his chapter presents some

conceptual tools used to analyse priate higher education in deeloping countries, which

is also applied to the case o Saudi Arabia. 1he types and unctions o priate higher

education institutions are sureyed, and key categories or deining and understanding

priate institutions are presented. linally, I make use o the typologies produced by

Ley ,1986a, and Geiger,1986, in identiying key unctions o priate higher education.

:$Q)")"* ,%)-('$ .)*/$% 0#12(')3"

Scholars such as Altbach ,1999,, Geiger ,1986,, and Ley, ,1986b, 1999, 2002,

acknowledge the complexity o deining priate higher education and agree that there is

no uniersal deinition applicable to institutions in dierent countries and regions. 1he

sector emerged diersely in dierent countries with dierent histories and contexts

,Altbach, 1999,. Lery nation, to some extent, has its own criteria which dierentiate its

public and priate higher education institutions. 1hese criteria are dierent rom those

in other national contexts. Boundaries between the two sectors in arious regional and

national contexts are becoming increasingly blurred, with priatisation taking place

within the public sector and with arious degrees o state control and superision oer

the priate sector ,Altbach 1999, Ley, 1986b, 2002, 2003,.

1hereore, there is a need to understand how priate higher education is related to the

concept o priatisation`. Butler ,1991, p. 1,, deines priatisation as a shiting o a

unction, either in whole or in part rom the public sector to the priate sector`.

According to Maldonado et al. ,2004,, priatisation in higher education coers a

spectrum o organisational orms. At one end is the public higher education institution

priatising` aspects o its operation, while at the other end is the priate sector,

26

establishing institutions designed to be seen as separate rom those which all within the

public sector. 1he latter type will be considered here, and will orm the main ocus o

this study-priate higher education in Saudi Arabia.

1o exempliy this critical approach o unction shiting`, one must irst identiy hybrid`

orms which blur the boundaries between public and priate sectors. 1his would include

those established by public uniersities. Murphy ,1996, describes a range o orms o

organisation, including priatisation o serices by contracting them to the priate

sector: an example o this is the leasing o internal printing and reprographic serices to

a priate contractor to operate exclusiely within a uniersity, another example is a sub-

contractual arrangement with a catering company to proide a ull range o serices

throughout the institution.

Another orm o priatisation may be identiied as cost-shiting`. An example o this is

when public higher education institutions begin to charge tuition ees to students to

coer some o their costs. In eect, this means charging or public serices which were

preiously paid by the public purse. A urther example o a orm o priatisation is the

establishment by a public higher education institution o an independent company, or a

cost unit, or a corporation with operational autonomy as a way o generating extra

reenue. Varghese ,2004, called this type o priatisation the Corporatisation o

Uniersities`.

1hese cases o priatising` public higher education reeal the blurring boundaries

between the public and priate sectors. 1his distinction is also blurred by the tendency

or priate institutions to operate like public bodies. Ley reers to this as

isomorphism` ,Ley, 1999,. In some cases, institutions are coerced to assume certain

organisational orms, while or others certain orms are adopted or purely commercial

reasons, a sort o copying or mimicry ,mimesis,. One thereore oten sees tactics used to

disguise certain aspects o a priate higher education organisation, or instance the

adoption o the curricular outline o an accredited public counterpart by a priate

institution to ensure its own accreditation.

Ley suggests that this blurring between public and priate is increasing and that almost

the only way to dierentiate between the two sectors is through identiying their legal

status ,Ley, 198b,. According to Ley ,1986b, ...no behaioural criterion or set o

criteria distinguishes institutions legally designated priate rom institutions legally

designated public.` ,p. 10,. 1his iew will be examined in relation to Saudi Arabia.

27

Based on my readings o the scholarship on priate higher education ,Altbach, 1999,,

Geiger ,1986,, and Ley ,1986a, 1986b,1999, 2003,, the key categories used in analysing

the priate sector are presented in the table below:

B(6;$ JY ,$%&<$2')-$& Q3% 1"#$%&'("#)"* <%)-('$ .)*/$% 0#12(')3"

Perspecties in

understanding priate

ligher Lducation

lunding

Dierent types o inancial resources it relies

on

Ownership

1he extent to which it is owned by priate

inestors,bodies

Orientation

1he extent to which it is about:

1,1eaching,

2, Research,

3, Religion or

4, Market oriented

lunctions and Roles

1he extent to which it aims to proide

1, \ider access to higher education,

2, Dierent orms o higher education, or

3, ligher quality education

Goernance

1he extent to which it is subject to direct

goernment superision

*Baseu on the woik of Altbach(1999), ueigei (1986), anu Levy (1986a,

1986b,1999, 2uuS)

1he ollowing sections inestigate these dimensions and will present the complexity o

deining priate higher education using any o these criteria alone ,Ley, 1986b,. I shall

examine how these perspecties are explored in studies o priate higher education, and

to what extent they can be applied to the Saudi context.

28

D1"#)"*

lunding used to be the most clear-cut distinction between public and priate higher

institutions. loweer, many goernments since the 1980s hae endorsed polices which

support the cost-sharing o higher education. 1he introduction o such policies around

the world represented a shit in ideology rom perceiing higher education as a public

good` to seeing it as a priate good` ,Johnes, 2004,. Although sources o inancing

ary among priate higher education institutions, Altbach ,1999, and Ley ,1992, 2003,

hae shown how the majority o priate ones rely upon tuition ees as their main source

o unding. In the USA, or example, reliance on tuition ees has a long history. A small

number o priate institutions also hae external sources o unding, such as sponsoring

by religious organisations. Resources may also take arious orms such as endowments,

student grants, loans, research grants, or alumni contributions ,Altbach, 1999,. Indirect

supports rom goernments towards priate institutions can also take the orm o

research contracts. 1his is the case with most elite priate institutions in the USA, where

goernment-sponsored research is undertaken ,Altbach, 1999,. Using the source o

unding to identiy priate higher education institutions thus can be conusing. Many

public higher education institutions now charge their students and some priate

institutions receie unds rom goernments ,Ley, 1986a,. Altbach ,1999, suggests that

the only dierence which can be ound in this regard is that tuition ees in public higher

education institutions are not the main source o unding, rather, each public institution

has its budget allocation within the total goernment budget. In addition, there are

priate higher education institutions, such as some in lolland and Belgium, which

receie unds rom their goernments, much equal to the public counterparts ,Geiger,

1986,. 1hereore using unding as a criterion is not suicient in examining the nature o

higher education institution.

Sources o unding, howeer, can still be a reliable dierentiating actor between public

and priate higher education institutions when the public sector does not charge

students any ees. In Saudi Arabia or example, public sector education is still tuition-

ree, the exception being a small number o programmes which hae been recently

introduced to the sector. Students in the public sector are also proided with a monthly

stipend. 1he Goernment has only recently begun oering inancial support towards

priate higher education institutions, which will be discussed in detail in Chapter 10.

Since 2010, goernment scholarships hae been aailable to und up to 50 o those

enrolled in priate institutions, based on their indiidual merits. No stipends are paid.

29

As will be seen, there is no culture o goernment support towards priate higher

education in Saudi Arabia.

CV"$%&/)< ("# E3-$%"("2$

1he legal ownership o higher education institutions is ound to be less ambiguous than

other criteria to classiy institutions as public or priate ,Ley, 1986b,. Altbach ,1999,,

howeer, points out the signiicant ariations o ownership within and between

countries. Priate institutions could be owned by either non-proit or proit-making

agencies, or both. Indiiduals or companies might also own priate higher education

institutions, as in the case o the Uniersity o Phoenix, which is owned by the Apollo

Group ,Kinser & Ley, 2006,. According to Altbach,1999,, in most parts o the world

priate colleges and uniersities began as non-proit institutions and were legally

established by religious organisations. loweer, proit-making higher education

institutions hae recently emerged and been expanding at a rapid rate ,Kinser & Ley,

2006,.

Varghese ,2004, adds to Altbach`s ,1999, obseration by discussing another orm o

ownership in which priate institutions work with oreign collaborators. le explains

how an institution might be set up in one country but owned by indiiduals in another,

a orm o transnational ownership. 1he term transnational` here is used in the sense

employed by McBurnie and co-authors ,2001,, in which learners are located in a

dierent country rom where the awarding institution is situated. According to Altbach

,1999, transnational priate proiders are usually based in deeloped countries, e.g. the

UK and Australia, and receiers are in deeloping countries. 1his type o proision has

seeral adantages or the receier country, such as absorbing the excess demand or

higher education, decreasing the brain-drain` phenomenon occurring mostly in

deeloping countries, helping students to be with their amilies, and most importantly,

saing the expenses o earning a degree abroad ,Altbach, 2005,. lor example, the

Uniersity o Nottingham has established campuses in Malaysia and China, and Cornell

Uniersity in Qatar.

Australia and the UK present an interesting case, in which public uniersities hae

established transnational` priate arms, through setting up oreign campuses and

proiding distance education serices to students in other countries, mostly in South

Arica, Asian countries, and in the Paciic regions. 1hat means that these higher

Su

education institutions are public in the home country whereas priate in their host

country. Public higher education institutions rom deeloped countries are establishing

sub-branches in other deeloping or transition countries ,Varghese, 2004, imitating the

ranchise model o the commercial world.

In the Gul nations, or example, 1he higher education boom o the 1990s was marked

by a reaching out to \estern higher education institutions and, to a lesser degree, Asian,

or collaboration in the deelopment, administration, curricula, aculty recruitment and

training, and quality standards o these new national institutions. Coman notes the

unquestioned dominance o the American uniersity model in the Gul` ,2003, p. 1,.

Characterising these many new collaborations is not easy. Seeral terms are used such as

ailiations`, loose ailiations`, partnerships`, alliances`, branches`, or satellite

campuses` o \estern or Asian institutions. But these terms can be easily conusing and

their meanings oerlapping.

\illoughby constructs what I beliee is the most useul typology or these arious new

ailiations. le points out ie existing models: 1, symbolic association 2, ormal

superision 3, ormal endorsement 4, subcontracting, and 5, branch campus

,\illoughby, 2008, pp. 14-15,. Among them, symbolic association` denotes a Gul

institution collaborating with an external partner in deeloping its academic programme

which is modelled on those o its partner` ,\illoughby, 2008,. lormal superision`

occurs when the external partner deelops and monitors parts ,or all, o the academic

programme. lormal endorsement`, which may oerlap with ormal superision,

describes a Gul institution obtaining the endorsement o its programme ,or institution,

by an external partner who normally proides credentialing serices to higher

education institutions in the \est` ,\illoughby, 2008, p. 14,. In eect, such an

endorsement means the Gul institution is comparable to the \estern institution.

\illoughby`s ourth model-subcontracting`-designates a Gul institution which

obtains its initial academic and administratie sta to deelop the new institution

through the external partner. 1he Gul institution may then hire its own sta but asks

its \estern partner to oersee either all or part o its academic and administratie

deelopment`. 1his oersight will then in turn create a more credible academic

institution` ,\illoughby, 2008, p. 15,. 1he ith model-branch campus`-is a ariant

o subcontracting. 1he prospectie Gul entity does not seek \estern help in setting up

its institution. Instead, the \estern institution is inited to create a branch campus .

S1

with the power to grant a degree in the name o that ,\estern, uniersity` ,\illoughby,

2008,. In essence, the \estern institution exercises control oer all major elements o

the school.

\illoughby`s models proide a spectrum o choices relecting greater or lesser amounts

o control by the external \estern partner. 1he choice aced by the Gul institution-its

ounders-is: low much do they want to exercise control, ersus how much credibility

do they wish the institution to hae rom a particular association with a \estern

uniersity

In Appendix 2, \illoughby`s ie models are applied to all o the 54 new Gul

institutions with \estern ,and Asian, ailiations which hae opened between 1992 and

200. 1he large number and ariety o models clearly indicate that the Gul is a centre

or educational innoation. \illoughby links this phenomenon to the oil wealth o the

region, the extreme dependence on oreign skilled workers, the preious weakness and a

lack o deelopment o the education sector. A urther signiicant actor is the high

population growth rate o the region as a whole. 60 o the Gul population is under

16 ,Coman, 2003,. So the demand actor in the education sector is immense. In the

Gul, priate higher education is seen as a means o ensuring quality o instruction and

the releance to market needs that hae been missing rom the public uniersities`

,Coman., p. 3,. As we shall see, this is ery much the case in Saudi Arabia.

1hese new Gul ailiations ,see Appendix 1, with the \est ,and Asia, include

institutions o a remarkable diersity. Oman has ailiations with uniersities in Lngland

,Bedordshire, Leeds, and Coentry,, Scotland ,Glasgow Caledonian Uniersity,, the

USA ,Carnegie Mellon, Uniersity o Missouri-St. Louis,, Leipzig Uniersity, and

uniersities in India and Australia. Kuwait has partnerships with multiple Indian

uniersities, an Australian uniersity, and Dartmouth College. Qatar has ailiations with

American uniersities ,Cornell, Georgetown, Virginia Commonwealth, 1exas A&M, as

well as ClN Uniersity o ligher Proessional Lducation in 1he Netherlands. Bahrain

has relationships with the Uniersities o London, Leicester, and 1he Royal College o

Surgeons ,Ireland, as well as 1he Uniersity o Newoundland ,Canada,. 1he UAL

presents a dizzying array o priate institutions that are quickly eclipsing the

goernment uniersities` ,Coman, 2003, p. 2,. 1hese include partnerships with

uniersities in India, Pakistan, Malaysia, Belgium, Australia, \ales, Scotland, USA, and

S2

in Lngland. Although these many new joint entures in the Gul are still new, their

impact are likely to be socially and economically signiicant:

1he act that so many uniersities and colleges hae come into existence suggest

that there are strong social and political dynamics within the region supporting the

deeper economic integration o Gul societies with global and regional economic

lie. ,\illoughby, 2008, p. 29,.

In Saudi Arabia, no transnational institutions exist yet, as no oreign ownership is

allowed - unlike in many countries where ownership by oreign indiiduals is permitted,

Saudi Arabian law requires that there be at least ie partners acting jointly as owners. A

company may also be an owner. Non-proit status and proit-making status are both

permitted or priate institutions. 1he majority o priate institutions, howeer, are

operating on a proit-making basis. 1his complexity in orms o ownership and in legal

status highlights the diiculties o deining the priate`, as any orm o ownership in

Saudi Arabia is heaily conditioned by regulation and control. 1he extent o control

which Saudi goernment has on the sector is discussed throughout the ollowing

chapters. As Ley has written ,1986a,, the status o legal ownership does not reeal how

the institution actually unctions. le has shown that in many cases priate higher

education institutions are ound to be less autonomous than their public counterparts,

which are completely unded by the goernment. Pachuashili ,2011, also explains how

in a post-communist setting, legally deined non-proit and proit-making priate

institutions can hardly be dierentiated as both o them rely mainly on tuition ees, and

hae a market orientation.

"#$%&'('$)&

Priate higher education institutions ary in their orientation: some are research-

oriented, others are religiously ailiated, while others are specialised institutions

,Altbach, 1999, Geiger, 1986, Ley, 1986a, 1986b, 2003,. Most prestigious priate

uniersities hae a research ocus ,Altbach, 1999,. According to Ley ,1992, 2003, and

Altbach ,2005,, the religiously ailiated institutions used to constitute the majority o

priate institutions world-wide. loweer, their dominant position is diminishing as

specialised institutions are coming to lead the market, such as colleges ocusing upon

business and inance, legal, or medical studies, rather than oering a ull range o

academic subjects ,Altbach, 1999,. Ley ,1999, 2003, 2006a, 2006b, asserts that recently

SS

deeloped priate higher education institutions possess a unique potential, which allows

them to ill certain special niches in preparing graduates or uture employment.

One piece o eidence which Ley ,1986a, uses to highlight the distinctieness o

priate institutions is their mission statement. Ley argues that the mission o priate

higher education institutions is less inclusie and broad, ocusing rather on speciic

target markets. 1he students they seek to attract tend to be narrowly ocused, selectie,

and specialised themseles. le urther ,1986a, 2002, 2006a, obseres that priate

institutions concentrate on ields which are related to uture` jobs. Notwithstanding the

aboe, some studies criticise programmes oered by priate institutions or giing

priority to priate beneits oer social ones. lor instance James ,1991a, p.193-194,

argues that research and broad educational needs are less important to the priate

sector.

Some studies point out that priate institutions concentrate on ields that are less

expensie to teach and maintain. Comparatie study by 1eixeira and Amaral ,200,

similarly ind priate higher education institutions to hae a low-risk` strategy and

concentration on low-cost and ,sae initiaties. loweer, there are exceptions, such as

priate higher education institutions oering ery expensie courses o study, such as

medicine, as is the case n the KSA. 1his will be examined more ully in later chapters.

In terms o orientation, Saudi priate higher education is not characterised by a ariety

o religious ailiations, unlike in other nations where Islam or Christianity is the

dominant and,or institutional religion. A particular school o Islam is aoured and

imposed throughout the country`s institutions. But it must be stated that unlike a

country such as the USA, no priate higher education institution in the KSA ocuses on

religious ,Islamic, studies also in contrast to some o their counterparts in the public

sector. Also, most o the Saudi Arabian priate institutions are ocused on teaching

rather than research, with only one exception - the King Abdullah Uniersity o Science

and 1echnology ,KAUS1,, a new research uniersity.

Beore I end my discussion in this section, I also want to discuss briely a special higher

education institution, as it may shed some interesting lights on the uture deelopment

o higher education in the KSA. In September o 2009 King Abdullah Uniersity o

Science and 1echnology ,KAUS1,, a graduate-leel research uniersity was opened or

admission. Located by the Red Sea about 50 miles rom Jeddah, KAUS1 has a ast

campus--36 sq. kilometres--which includes a marine sanctuary and research acility--and

S4

a small city contained with its borders. 1he cost o the project-->12.5 billion--comes

with the inancial support rom King Abdullah and the royal amily. A >10 billion

endowment und is also being created or the Uniersity ,Cambanis, 200,. lor

students who are admitted, tuition is ree with additional stipends. Graduate students

may receie stipends o up to >20,000 per year. KAUS1 oers both M.Sc. and Ph.D.

degrees.

1he King bypassed the MOlL by selecting ARAMCO ,the country`s state oil

company, to deelop the initial plan, build the campus and assist in curriculum. 1he

Uniersity o 1exas ,Austin,, the Uniersity o Caliornia ,Berkeley, and Stanord

Uniersity hae partnered with KAUS1 to deelop speciic curricula and assist with

selecting aculty ,KAUS1, 2012,. 1hese are among the irst such \estern ailiations in

Saudi Arabia. KAUS1 is ocused on applied research and has established multi-

disciplinary research centres. 1hese centres will pursue research in areas such as clean

combustion, solar and alternatie energy science, water desalination and computational

bioscience. KAUS1 may sere another unction ital to the Kingdom`s uture--the

training o the next generation o uniersity proessors. Dr. Mohammed Kuchai, a

microbiologist at KAAU, remarked: Saudi Arabia is projected to need 100,000

uniersity sta by 2030 but only has 40,000 today so training uture sta is a priority`

,Sawahel, 2006,.

KAUS1 also represents a ery signiicant departure rom traditional Saudi social norms.

Men and women are on the same campus and attend the same classes. 1his is the irst

time this has been allowed in the Kingdom. \omen are not required to hae their

heads coered in class and may drie on campus. In addition, non-Saudi students may

also enrol. 1he entire Kingdom will be closely watching the results o this educational

and social experiment.`

In general comparison, Saudi Arabia`s priate institutions are more market-oriented in

their degree programmes and course works. 1his will be urther explored in Chapter 6

SS

Functlonx unJ Rolex: lfferent, Better, unJ More

In this section I shall explore the unctions and roles o priate higher education in the

light o what I call three assumptions`. 1hese three assumptions reoled around the

emergence and deelopment o the priate sector in higher education world-wide. 1o

one extent, the priate sector is set to proide more educational opportunities or to

oer dierent orms o education than is proided by the existing public sector, or to

introduce educational proision o higher quality as a response to a public sector which

ails the expectations o its stakeholders.

Geiger ,1986, and Ley ,1986a, hae obsered that priate higher education institutions

around the world also ary in their missions. 1hey both discuss qualitatie` and

quantitatie` roles or priate higher education in each country, which emerged to ulil

a speciic role or unction ,Ley, 1986a, 1999, 2003, Geiger, 1986,. Ley ,1986b, 2010b,

identiies three waes` which appeared in sequence. 1he Q)%&' wae represents the

establishment o priate higher education to accommodate the needs o certain religious

or ethnic,identity groups. 1he &$23"# wae is marked by the establishment o elite

priate institutions as a reaction to the mass orientation o public higher education

institutions, when students are looking or prestigious orms o education. In Latin

America, or example, public higher education growth came irst as a religious response

to public sector secularisation , and then as an elite response to a massiying and socio-

economically more open public sector open ,Ley, 1986a,. 1he '/)%# wae witnesses

the establishment o priate institutions to absorb the excess demand on higher

education which the state public sector can no longer ulil. le adds, howeer, that

demand-absorbing institutions may cross these category boundaries and also hae a

religious orientation and,or be prestigious.

Geiger ,1986,, working at the same time as Ley, deelops his ideas along similar lines.

le describes three main unctions or priate higher education institutions. 1hey are to

proide more`, better`, and dierent` education. 1he more` unction occurs when

priate higher education institutions exist to absorb an immense demand which public

institutions cannot meet. 1he priate sector in this case becomes a mass` sector, and

thus becomes the major proider o higher education. 1he reason behind the public

sector`s inability to meet the demand or higher education is usually because those

public institutions are small in size and hae restrictie admission policies. loweer, the

quality o priate higher education institutions which ulil this more` unction is

S6

questioned. 1hese are the institutions which Ley ,1986b, describes as demand-

absorbing`. In deeloping countries, most priate higher education is belieed to all

within this category ,Ley, 2003, 2006b,. In countries where public-sector education is

limited and deicient, a large non-selectie priate sector is oten deeloped to proide

or the large group which is expelled rom the public sector, such as happened in the

Philippines ,James,1991a,.

1he second unction, outlined by Geiger, is to proide dierent` education. Priate

higher education institutions are ound to exist een when the public sector has the

capacity to absorb the demand or places in higher education. 1his role is played when

the state allows priate proision to respond to certain needs which are not met by the

public sector institutions. An example o this is the necessity o public sector colleges to

be aailable or all, thereore they cannot discriminate in aour o minority groups.

Ley ,2011, has urther categorised this type o institution under the identity` type. An

example o an identity institution is the Catholic Uniersity o Korea, a priate

institution with a history 150 years. It seres a distinct minority group within the country

o speciic cultural and religious orientations. 1hus, the public sector in this case is not

aced with a capacity issue, but rather an issue o a demand rom speciic cultural groups

to hae access to a distinctie orm o higher education, which is obiously outside their

norms o higher education proision. \here cultural, social, and economic diersity is

alongside a strong and relatiely uniorm public sector, the priate sector can exploit the

demand or distinctie orms o proision. Supposedly, the issue o quality ,real or

perceied, may also encourage the growth o a high-quality priate sector.

In Geiger`s analysis o the dierent roles o priate higher education institutions, the

third unction is to compensate or the low quality ound in the public sector by

proiding better` education. In this scenario the priate sector is o a higher quality and

is perceied by students and their parents as oering a better alternatie to a ailing

public sector. Priate institutions may also oer courses o a quality matching what is

oered by the public sector, thus enhancing competition within the higher education

system.

Ley ,2011, proides a similar typology on priate institutions according to their criteria

or access and the clientele they sere. In addition to the identity` type, mentioned

aboe, his typology includes elite`, semi-elite`, serious demand-absorbing` and

demand-absorbing` priate institutions. Priate institutions become elite`, not or

S7

sering priileged clientele but or their academic and intellectual leadership` ,Ley,

2009, p. 15,. Ley ,2010b, 2011, highlights the act that the USA is an exception to

haing priate elite` institutions, as this type mostly exists in the public sector ,Ley,

2009,. Llite priate institutions are distinct or their high selectiity and or their ocus

on research. Ley ,2009, obseres that research is rarely a concern or new priate

institutions. 1hereore, he categorises them as semi-elite` and ound their ocus to be

more upon practical learning and training. Ley ,2009,2010b, 2011, obseres that semi-

elite` priate institutions hae aerage leels o selectiity in recruiting students and

aculty, less than those o elite institutions` but more than those in the serious demand-

absorbing` category. 1he aerage selectiity and the high tuition ees o semi-elite

institutions imply that their clientele is ormed o those rom wealthier socio-economic

groups and with good academic standards. Like elite priate institutions, semi-elite ones

are thus less likely to be primarily addressing access` issues ,Ley, 2008, 2009,. Ley,

howeer, suggests that semi-elite institutions indirectly contribute to increasing access to

higher education, as they:

,a, bring more inance to higher education, ,b, open public slots or others by

attracting some students away rom those slots,,c, diminish the low o domestic

students going abroad. ,Ley, 2009, p. 16,.

lis point is that when examining the place o such institutions within the wider higher

education system, one needs to look at the indirect impacts they exert. In addition,

serious demand-absorbing and demand-absorbing institutions are also sometimes

described as garage` institutions or diploma mills`, and are less selectie in recruiting

students and sta.

Demand-absorbing and serious demand-absorbing institutions are less selectie with

regard to student access. loweer, serious demand-absorbing institutions tend to hae

a clearer ocus upon their graduates` uture employability. 1hey thereore orient