Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Creating Langua G E-Ric H Presc Hool Classr Oom en Vir Onments

Uploaded by

brutedeepaxOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Creating Langua G E-Ric H Presc Hool Classr Oom en Vir Onments

Uploaded by

brutedeepaxCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Skills

shoes

coat

Creating Language-

Rich Preschool

dress

Classroom

Environments sneakers

Laura M. Justice

◆ Do children at your preschool have school districts that are attempting to Title I coordinator, a reading specialist,

strong language and literacy skills? implement language-rich classrooms a family resource specialist, a student’s

◆ Do children with language disabili- suggests that a team-based action plan parent, and the assistant principal. The

ties participate in general preschool incorporating the engagement and facilitator of the team should be the

classrooms? expertise of diverse local constituents is classroom teacher, who is most vested

◆ Do educators at your school collabo- the best route to actualization. The five in achieving a rigorous, doable, and

rate in language-rich curriculums? steps to actualizing a team-based action effective action plan.

◆ Do you have sufficient funding for a plan include identifying a team, devel- The key to creating and implement-

quality preschool program? oping a philosophy, designing the phys- ing language-rich classroom environ-

These are broad, ambitious ques- ical space, designing daily language ments is infusing the classroom with

tions, and we hope to set you on your plans, and ensuring quality adult-child rich adult-child interactions. One

way to answering them and ensuring interaction. Table 1 summarizes each of teacher and one assistant cannot do this

the success of all the children in your these five steps. job for 15 to 20 children. The subse-

preschool program.

TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 36-44. Copyright 2004 CEC.

quent steps in the action plan are under-

This article describes a systematic, Identifying a Team

taken by the entire team with the under-

team-based process for achieving lan- One team should be organized for each standing that each team member has

guage-rich classroom environments for classroom for which a language-rich made a commitment to being actively

preschool children (see box, "What

environment is proposed, Although involved in the classroom. By going

Does the Literature Say About

teams in a school can work together, through the next four steps, each team

Language-Rich Classroom Environ-

action plans need to be individualized member will be fully prepared (and

ments?"). A fictitious school, Dell

for each classroom. The team should committed) to contribute in a systemat-

Preschool, served as the program site

include everyone who is involved in ic, consistent way to the language rich-

for the five-step collaborative process

education and intervention for children ness of the classroom environment.

for achieving such environments (see

in the classroom, including the class-

box, “Dell Preschool”). Developing a Philosophy

room teacher, the classroom assistant,

A Collaborative Process for relevant specialists (e.g., speech-lan- Classrooms are idiosyncratic environ-

Creating Language-Rich guage pathologist, physical therapist), ments that reflect sociocultural aspects

Classroom Environments and any family resource coordinators. of the community being served, as well

It is, of course, one thing to know what The team should also include one or as administrative choices (e.g., curricu-

a language-rich classroom environment more parents and a program administra- lum), teacher values and skills (e.g.,

looks like and another thing to put one’s tor, if possible. One team at Dell instructional quality, physical organiza-

ideas and intentions into everyday prac- Preschool consisted of the classroom tion), and the children’s needs and

tice. My experiences as a consultant for teacher, the classroom assistant, the strengths. Once the team has been

36 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

What Does the Literature Say About Language-Rich Classroom Environments?

What Is a Language-Rich Classroom meaningful variation in the language to interrelated elements of language that

Environment? A language-rich class- which they are exposed. For instance, form the complex whole of oral lan-

room environment is one in which chil- when interacting with children, adults guage. Content consists of the words that

dren are exposed deliberately and recur- vary the abstraction level of the lan- are used and the concepts that are

rently to high-quality verbal input guage that they use. Variations in the expressed; this term is more or less syn-

among peers and adults and in which abstraction level allow children to par- onymous with vocabulary, or semantics.

adult-child verbal interactions are char- ticipate in perceptually oriented conver- Form refers to the way that word struc-

acterized by high levels of adult respon- sations in which they use language to ture and sentence structure are organ-

siveness. The five key elements of this label, imitate, and describe, as well as in ized grammatically and phonologically.

definition are in its explicit references to conceptually oriented conversations Use refers to the ways that language is

(a) exposure, (b) deliberateness, (c) that engage children in using language used in functional contexts to achieve

recurrence, (d) high-quality input, and to hypothesize, summarize, predict, social purposes. Children's content,

(e) adult responsiveness. decide, and reason (van Kleeck, Gillam, form, and use achievements directly

Exposure means that children experi- Hamilton, & McGrath, 1997). reflect their experiences with language

ence high-quality linguistic input both Recurrence refers to the importance in the world around them (Hart & Risley,

passively and actively within the class- of repetition to children's acquisition of 1995). Thus, exposing children to lan-

room (Bunce, 1995). They are exposed important linguistic concepts. This point guage that is diverse in these three areas

to language throughout the day in is demonstrated well in studies that is an important feature of the language-

diverse contexts and interactions. In have investigated young children's rich classroom, as shown in Table 2.

some of these exposures, the child may acquisition of new vocabulary words Adult responsiveness means that

not be an active participant; rather, chil- when someone reads storybooks to adults frequently and consistently

dren may be passive observers of the them. Robbins and Ehri (1994), for respond to a child's communicative acts

language that is used around them. instance, showed that the probability in a way that is sensitive to the child's

Children do not need to overtly produce that young children would learn a new developing competencies. High levels of

or imitate language to acquire key lan- word from a storybook was consider- responsiveness by teachers and

guage forms and concepts, since inci- ably greater if the word occurred twice parents—particularly when adult

dental exposures to language in which in a storybook rather than only once. responses focus on child-initiated top-

children are merely bystanders can be Penno, Wilkinson, and Moore (2002) ics—have repeatedly been associated

sufficient for language learning to take found that children's use of new vocab- with robust language gains by children

place (Akhtar, Jipson, & Callanan, ulary words from storybooks increased (Girolametto & Weitzman, 2002). In

2001). Nevertheless, active experiences in a progressive manner from the first addition to being responsive to all com-

are also important for language acquisi- reading session to the third one as chil- municative acts of children, adults

tion, and children require opportunities dren experienced new words repeatedly should ensure that their responses are

to use their language when they interact over readings. In language-rich class- contingent; a contingent response is one

with others. rooms, repetition is valued and is an that responds to a child's communica-

Deliberateness means that the adults integral part of the classroom routine. tive intent rather than to the "correct-

in the classroom are intentional in the Children receive multiple opportunities ness" of the child's act. For instance, an

language that they choose to use with to experience specific linguistic con- adult who responds "Oh, that wasn't

children. When talking with children, cepts in diverse contexts of use, and very nice!" to a child's "Her hitted me!"

adults in language-rich classroom envi- classroom experiences are organized to is responding contingently; the adult

ronments make knowledgeable choices foster repetition. has focused on the child's meaning and

in the words, grammar, and sounds that High-quality input means that adult communicative intention rather than on

they use so that they can stimulate chil- language in the classroom is character- the words and grammar that the child

dren's ongoing achievement of new ized by diverse content, form, and use. used.

skills. Adults provide children with Content, form, and use are the three

organized, the next step in developing a ronments. A philosophy is essentially a ical environment of the classroom,

language-rich classroom is for the team set of principles that all team members designing daily lesson plans, and inter-

to construct a philosophy that is indi- will translate into everyday practices. A acting with children.

vidualized to the classroom environ- philosophy about oral language—what The team must thus develop a state-

ment. By developing a philosophy, it is, how it is acquired, and why it is ment of its philosophy. From this state-

teams can take a principled approach to important—influences the choices that ment, it will derive operating principles

creating language-rich classroom envi- educators make in structuring the phys- for a language-rich classroom. The

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ NOV/DEC 2004 ■ 37

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

philosophical statement has three ele-

ments: (a) a definition of language, (b) Dell Preschool

a statement of why language is impor-

tant, and (c) a general statement indi- Many educators who work with pre- Dell Preschool. According to recent

cating how language is supported in the school children strive to immerse them data, one quarter of the preschool grad-

classroom. Although formal definitions in the richest oral language environ- uates fail the spring oral language

of language (e.g., language is “an arbi- ment possible. Educators at Dell screening in kindergarten; consequent-

trary code or system of symbols to com- Preschool, a fictitious name for the ly, the staff of Dell Preschool has

municate meaning” [Hallahan & school used as an example in this arti- ramped up efforts to create language-

Kaufman, 2003, p. 266]) may be useful cle, make this effort. rich classroom environments by design-

for getting started, translating formal The school's 36 students come from ing a team-based action plan.

definitions into everyday classroom high-poverty households. The pre- The staff adopted this team-based

experiences is difficult. Hence, teams school, which is funded through Title I, approach in light of recent public-poli-

should develop their own definition, is situated in a particularly mountain- cy initiatives asserting the importance

with guidance from team members who ous and remote county in the of collaborative partnerships in promot-

are most knowledgeable about how oral Appalachian region of the United ing the collective expertise of diverse

language develops and is best support- States. The per capita annual income in educators in preschool language inter-

the county is about $12,000 per year, vention (e.g., Snow, Burns, & Griffin,

and 30% of the adult population is 1998). Because of the influence of sev-

functionally illiterate. Nearly 20% of eral factors, language-focused initia-

A philosophy about oral

the children in the county school sys- tives similar to the one at Dell

language influences the tem receive special education services. Preschool occur in many preschool pro-

The oral language needs of children grams across the United States. These

choices that educators

attending Dell Preschool are consider- factors include increased awareness of

make in structuring the able. Like other children in disadvan- the association among oral language

taged circumstances, they could benefit foundations and later reading achieve-

physical environment of

from systematic, focused efforts to ment, sensitivity to the risk factors that

the classroom, designing ensure that they develop the oral lan- hinder children's achievement of strong

guage skills that can furnish the foun- language and literacy skills, participa-

daily lesson plans, and

dation for short- and long-term aca- tion of children with language disabili-

interacting with children. demic achievement. ties in general preschool classrooms,

Providing language-rich classroom and significant infusion of federal dol-

environments has long been a goal of lars to all such efforts.

the administrators and educators at

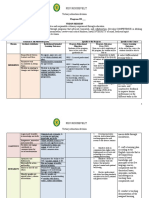

ed. Figure 1 presents the philosophy

that one Dell Preschool team developed.

This exercise may seem time-con- Designing the Physical Space ports for facilitating children’s exposure

suming and peripheral to the goal of The physical environment of a class- to diverse aspects of language content,

implementing a language-rich class- room has a coercive power over the form, and use. Two key supports that

room, but it is critical for several rea- quality and the quantity of children’s the team must explicitly and carefully

sons. First, some team members may be oral language experiences (Roskos & consider are how to organize the space

less knowledgeable about oral language Neuman, 2002). The environment medi- and how to obtain props and materials.

than others. This activity will be educa- ates the language that the teachers and Organization of space. Roskos and

tional for all, since the team works children use. In creating language-rich Neuman (2002) have identified four key

together to define language, discuss classroom environments, the physical attributes of spatial arrangements in

how language develops, and identify environment must provide ample sup- classrooms that researchers believe can

ways to support language in the class-

room (see box, “Theoretical Perspective

of Language”). Second, this activity Figure 1. Philosophy of the Deli Preschool Team

helps ensure that everyone on the team

is “on the same page.” It is important Philosophy: Language is a set of tools that we use to communicate our thoughts

that all team members subscribe to the

and feelings with one another. Language is essential for our full participation in

philosophy, and developing the class-

society as speakers, listeners, readers, and writers. In our classroom, language

room philosophy as a group activity

growth is supported by setting daily goals for vocabulary, grammar, phonology, and

promotes ownership by the entire team.

pragmatics; by designing activities that meet these goals; and by ensuring frequent

child-to-child, child-to-adult, and adult-to-child meaningful communication.

38 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

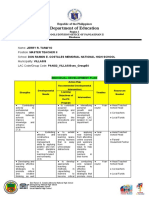

Table 1. Five-Step Team-Based Action Plan for Designing and Implementing Language-Rich

Preschool Classrooms

Step Actions

1. Identify a team • The team should include as many constituents as possible

who are involved with the preschoolers in the classroom.

• The team should include parents and administrators.

• All team members should commit to contributing in a system-

atic, consistent way to the language richness of the class-

room.

2. Develop a philosophy • The team develops a set of principles governing oral lan-

guage in the classroom that will translate into principle-based

everyday practices.

• The philosophy should define language, state why language

is important, and identify how language is supported in the

classroom.

3. Design the physical space • The team identifies how to organize the classroom space to

maximize language enhancement.

• The team identifies props and materials, including literacy-

related artifacts and real-world props.

• The team identifies community supports for donation of mate-

rials and props.

4. Design daily language plans • The team develops a set of objectives for the whole year for

linguistic content, form, and use.

• The objectives can reflect sociocultural values and state-level

policies (e.g., standards of learning).

• The daily language plan identifies key objectives and activi-

ties and is accessible to all who enter the classroom to "jump

in" and engage with children.

5. Ensure quality adult-child conversations • All team members should have training on adult-child inter-

action techniques that maximize children's language growth.

• Team members can mentor each other in the classroom for

quality implementation.

facilitate language learning and use. (1995) has effectively argued that dra- board), and various types of printed

First, the classroom should be organized matic play settings should be rotated materials (menus, signs, books, recipes,

to emphasize open space. Second, spe- daily (or at least weekly) to provide maps, and newspapers). Literacy-relat-

cific areas should be clearly identified children with rich opportunities to learn ed artifacts encourage children to use

throughout the classroom (e.g., library, about diverse aspects of their communi- language at an abstract, metalinguistic

dramatic play area). Third, a variety of ties. level and to view language as an object

materials should be available to chil- Provision of props and materials. Of of scrutiny. Literacy-related artifacts

dren, particularly materials that encour- particular importance in developing lan- also help children make connections

age creativity and problem-solving. guage-rich classroom environments are between oral and written language.

These materials should be clustered literacy-related artifacts, as well as real- Storybooks, a literacy artifact that

conceptually or schematically. Fourth, world props and materials. Literacy- should be widely available and readily

authentic, functionally complex dramat- related artifacts are materials that are accessible in every language-rich pre-

ic play settings should be available in associated with written language. They school classroom, provide children with

each classroom. Examples include an include, for instance, writing utensils an endless supply of familiar and unfa-

airport, a grocery store, a miniature (pens, pencils, and crayons), writing miliar linguistic forms, content, and use.

classroom, and a restaurant. Bunce media (envelopes, paper, and card-

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ NOV/DEC 2004 ■ 39

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

Real-world props and materials are

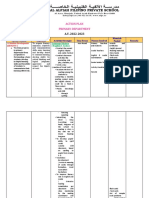

Table 2. Content, Form, and Use Experiences in Language-Rich

authentic tools that children use in their

Classrooms

play to represent life outside the class-

room. Exposure to these props and Content Experiences Children experience many different

materials, particularly with adult medi- word types, including adjectives, nouns,

ation, helps children learn new words, verbs, prepositions, and adverbs.

Children are exposed to the ways that

important societal concepts are

expressed, such as kinship (brother,

Language-rich classroom uncle, aunt), time (tomorrow, yester-

environments emphasize day), and shelter (house, apartment).

Children are exposed to gradations of

children’s acquisition of precision in using vocabulary (old,

language through their stale, musty), learn the multiple mean-

ings of words (run), learn to organize

interactions with both concepts (farmer, nurse, pharmacist),

peers and adults. and learn how to play with words (a

grasshopper man is a man who collects

grasshoppers). Children are exposed to

diverse ways to express similar things

develop schematic representations of (that towel, that white towel, the towel

community activities, and apply back- he has).

ground knowledge to new learning situ-

ations. Real-world props should be Form Experiences Children experience many different

rotated regularly to provide children grammatical constructions, including

with maximal exposure to new linguis- elaborated noun phrases (the old dark

tic concepts. house), various verb constructions

The team must collaborate to design (walks, is walking, will walk, walked),

the physical space of the language-rich and prepositional phrases (under the

classroom environment. A team table). Children hear sentences that are

approach engages creative and function- simple, complex, and compound; and

al contributions of diverse constituents they are exposed to diverse ways to link

in designing the physical space. It also ideas syntactically (e.g., If you want a

brings in the collective energy of a sticker, you need to come and get one).

group of people for such physical activ- Children experience question types of

ities as building partitions or painting many different constructions, including

the room for demarcating classroom auxiliary inverted (Is he going?), tag (He

areas. A team-based approach to the

is going, isn't he?), and the who, what,

when, why, where forms of questions.

physical design of the classroom can

also be useful for identifying communi- Use Experiences Children are exposed to the many ways

ty resources for materials and identify-

that language is used for social and

ing possible people or organizations

functional purposes. Children are

that might donate materials or props.

exposed to diverse speech acts (label,

At Dell Preschool, considerable time

repeat, answer, request, greet, protest)

and effort was focused on reorganizing

and learn conversational moves (initiat-

the classroom space to maximize its ing a topic, maintaining a topic, closing

support for children’s language skills. a topic). They listen to and produce sto-

The team scrutinized the classroom by ries that are organized temporally and

using The Early Language and Literacy causally, and they are exposed to strate-

Classroom Observation Toolkit (ELLCO; gies for solving communication break-

Smith & Dickinson, 2002) and the Print downs. They are encouraged to initiate

Environment Assessment Form with their peers, to take turns, and to

(Dowhower & Beagle, 1998; Taylor, negotiate for objects. They learn how to

Blum, & Logsdon, 1986), two instru- talk to different people (friends, teach-

ments designed to examine language ers, librarians) in different settings

and literacy richness in early childhood (schools, stores, homes).

classrooms. Teachers and assistants at

40 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

Dell Preschool used the results of these environmental circumstances are pres- Activities. The team should develop

instruments to identify explicit ways to ent. activities that correlate with the objec-

enhance language supports in the class- Identifying objectives for use in the tives on the daily language plan. The

room, such as increasing the amount of daily plans can be an a priori team activities support achievement of the

children’s print displayed on the walls, activity. The team should identify a objectives, and they can build on the

improving the variety of storybooks broad set of oral language objectives to existing organization of the classroom

available in the classroom library, be used and reused throughout the year day. For instance, Table 3 identifies a

decreasing the amount of time that chil- by brainstorming a list of general expec- content objective as “to understand and

dren spent in transitions between activ- tations concerning oral language goals use words of time (yesterday, tomorrow,

ities, and increasing the number and for children in their community or year, month).” A daily activity in the

variety of literacy artifacts available in classroom. State- and federal-level poli- classroom that can support this objec-

various classroom centers. cy documents may be useful in creating tive is the daily circle time, during

this list. Examples of objectives in con- which the teacher and children identify

Designing Daily Language Plans tent, form, and use that are appropriate the day, week, and year, as well as the

Adopting a philosophy and designing for 3- and 4-year-old children are listed weather. This activity provides a natural

the physical environment to support in Table 3. support for addressing the time content

oral language are not enough to ensure

the language richness of a preschool Theoretical Perspective of Language

classroom. Designing a daily plan with Language-rich classroom environments indicated that individual differences in

clear goals for language content, form, emphasize children's acquisition of lan- maternal and other caretakers' verbal

and use is also necessary to ensure an guage through their interactions with input can explain the wide variation in

intentional and deliberate focus on lan- both peers and adults. An emphasis on the rate of children's early language

guage in the classroom (Bunce, 1995). social interaction as a route to language growth and later language outcomes,

The daily plan is a road map for ensur- gains is consistent with social-interac- thereby lending support to social-inter-

ing that specific language targets are tionist developmental theory. Social- actionist accounts of language acquisi-

addressed throughout the day—every interactionist perspectives view lan- tion (e.g., Baumwell, Tamis-LeMonda,

day—in planned and incidental class- guage acquisition as a sociobiological & Bornstein, 1997; Landry, Miller-

room experiences. Although classroom process in which both innate biological Loncar, Smith, & Swank, 1997). Rush

teachers and assistants can develop propensity and frequent, sensitive ver- (1999), for instance, studied mother-

daily plans in advance (perhaps on bal input are critical for supporting lan- child interactions for 39 preschoolers

Monday for the entire week), adopting guage growth. Chapman (2000) indi- living in poverty and found a strong

an a priori organizational scheme for cates that the "socio" part of the equa- negative correlation between the

the daily plans is the responsibility of tion includes "frequent, relatively well- amount of time that children spent

the entire team. The entire team must tuned affectively positive verbal interac- playing alone and their expressive and

be knowledgeable about the structure tions," which are considered a critical receptive vocabulary skills. Reci-

and the content of the plan. The daily locus of support in early language procally, strong positive correlations

language plan should be readily avail- acquisition (p. 43). This perspective were observed between the rate of

able to any person (particularly team emphasizes the importance of socially maternal one-on-one vocal responses to

members) who enters the classroom, so embedded, mediated interactions with children and children's vocabulary

that he or she can assist in meeting its more knowledgeable conversational skills.

objectives. Daily language plans have partners as a critical developmental Similar patterns have been found

two components, objectives and activi- mechanism for children (Justice & when examining children's oral lan-

ties. Ezell, 1999; Justice & Kaderavek, 2002). guage skills and their interactions with

Within such interactions, the more such other caregivers as preschool

Objectives. Objectives identify spe-

knowledgeable partner, such as the teachers and day-care providers.

cific targets in language content, form,

teacher, fine-tunes her or his verbal Girolametto and Weitzman (2002)

and use (Bunce, 1995). The daily lan-

input to scaffold the child's commu- showed that the rate of day-care

guage plan should include at least one

nicative engagement and gradual move- providers' use of techniques that

objective in each area that is addressed

ment toward more independent levels Girolametto and Weitzman consider

for all children in the classroom on a

of linguistic skill. characteristic of "conversational

given day. This systematic focus on con-

Social-interactionist accounts are responsiveness" (e.g., imitations, label-

tent, form, and use ensures that no area

useful for interpreting the differences in ing, and expansions) can explain varia-

is underemphasized in the language-

language acquisition in individual chil- tion in children's language productivity

rich classroom. Content, form, and use (i.e., the amount of language produced

dren that appear to be mediated by

are equally important parameters of lan- variations in quality and quantity of by children), as well as their vocabulary

guage; and each area is susceptible to language input. Much research has and grammar use.

delays when adverse developmental or

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ NOV/DEC 2004 ■ 41

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

objective. By identifying specific objec-

tives and correlated activities at the start Table 3. Examples of Objectives in Content, Form, and Use

of each day, the focus on oral language

Content 1. To understand and use words of time

enhancement becomes deliberate and is (yesterday, tomorrow, year, month)

likely to be more effective. An example 2. To understand and use words of emo-

of a daily language plan is presented in tion (sad, happy, angry, excited)

Figure 2. 3. To understand and use words of trans-

portation (car, tractor, airplane)

Ensuring Quality Adult-Child

4. To understand and use words of emo-

Conversations

tion as noun descriptions (the happy

With a philosophy, a supportive physi- boy, the sad bunny)

cal environment, and daily language 5. To categorize words (bear, cat, and

plans in place, there is one final, and dog are animals)

essential, element for the language-rich

preschool environment: ensuring the Form 1. To add -er to words to make "worker"

quality of adult-child conversations. words (a person who farms is a

A social-interactive perspective of farmer)

language acquisition emphasizes the 2. To understand and use personal pro-

importance of frequent well-tuned com- nouns (I, we, he, she, it)

municative interactions in children’s 3. To understand and use plural forms

achievement of language content, form, (shoe/shoes)

and use (Chapman, 2000). Variations in 4. To elaborate nouns with articles and

the quality and quantity of the language adjectives (the fast, green car)

that children experience in their homes 5. To use future-tense verbs to discuss

and classrooms partially account for future events (we will go)

individual differences in the rate of chil-

dren’s language accomplishments (Gir-

Use 1. To initiate to peers when needing

olametto & Weitzman, 2002; Hoff,

help or wanting something

2003). This line of research has impor-

2. To maintain a topic for two or more

tant implications for the design of lan-

turns in a conversation

guage-rich preschool classrooms.

3. To follow or give directions with two

A language-rich classroom environ-

or more steps

ment thus must involve adults who

4. To tell a personal event as a story to

deliberately use language-stimulation a peer

strategies when conversing with chil- 5. To use language for many different

dren. Table 4 presents eight key strate- purposes (e.g., question, comment,

gies, as identified by Girolametto and request action, request information,

Weitzman (2002) and Bunce (1995). reply, greet, and leave)

They are (1) waiting, (2) pausing, (3)

confirming, (4) imitating, (5) extending,

(6) labeling, (7) open questioning, and tent, and uses. These responses include A team approach is essential so that

(8) scripting. labeling and scripting. Together, these all team members fully understand,

Girolametto, Weitzman, and strategies constitute high-quality verbal appreciate, and achieve quality use of

Greenberg (2003) differentiate these input by adults. By using these tech- these eight techniques. Conversations

techniques into child-oriented respons- niques, adults reduce their directiveness between adults and children that are

es, interaction-promoting responses, and increase their responsiveness and characterized by adult use of waiting,

and language-modeling responses. sensitivity to children’s developing lan- pausing, confirming, imitating, extend-

Child-oriented responses, which are guage competencies. In turn, when chil- ing, labeling, open questioning, and

used to create and maintain a shared dren interact with adults who are using scripting are the core of the language-

conversational focus between adult and these techniques, the children produce rich preschool classroom. Indeed, a

child, include waiting and extending. more language that is lexically and classroom may have an outstanding

Interaction-promoting responses, which grammatically complex (Girolametto & philosophy, an exemplary physical

encourage the child into active dialogue, Weitzman, 2002), which leads to arrangement, and a deliberate daily lan-

include pausing, open questioning, imi- improved language achievements dur- guage plan; however, without adult-

tating, and confirming. Language-mod- ing the preschool period (Rice & Hadley, child conversations of sufficiently high

eling responses provide children with 1995). quality and sensitivity, these efforts are

demonstrations of linguistic forms, con-

42 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

environments that are most beneficial to

Figure 2. Sample Daily Language Plan their early development.

Daily Language Plan: Dell Preschool References

Thursday, October 9 Akhtar, N., Jipson, J., & Callanan, M. (2001).

Learning words through overhearing.

Teacher: Miss Harden Child Development, 72, 416-430.

Baumwell, L., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., &

Today’s Objectives Specific Activities

Bornstein, M. H. (1997). Maternal verbal

1. To understand and use labels asso- 1. During circle time, the children sensitivity and child language comprehen-

ciated with clothing (content) will take turns asking one another sion. Infant Behavior and Development,

2. To understand and use plural to identify their favorite piece of 20, 247-258.

clothing. Bunce, B. H. (1995). Building a language-

forms (form)

focused curriculum for the preschool class-

3. To ask questions to peers (use) 2. During circle time, we will dress

room (Vol. 2). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

4. To ask for help when needed (use) the puppet and talk about each Chapman, R. (2000). Children’s language

piece of clothing. learning: An interactionist perspective.

3. During dramatic play, a shopping Journal of Child Psychology and

store will be set up so that children Psychiatry, 41, 33-54.

can shop for clothes. Dowhower, S. L., & Beagle, K. G. (1998). The

4. During art, the children will paste print environment in kindergartens: A

articles of clothing (felt) on pic- study of conventional and holistic teach-

ers and their classrooms in three settings.

tures of themselves.

Reading Research and Instruction, 37, 161-

190.

Ezell, H. K., & Justice, L. M. (2000).

not likely to result in the desired child ing by using videotapes (Ezell & Justice, Increasing the print focus of shared read-

ing interactions through observational

outcomes. 2000; Girolametto et al., 2003). Adults

learning. American Journal of Speech-

Although some excellent educators can observe on adult models video who Language Pathology, 9, 36-47.

may frequently use these strategies are using particular strategies while Girolametto, L., Hoaken, L., Weitzman, E., &

when interacting with children, studies they interact with children, and they van Leishout, R. (2000). Patterns of adult-

of preschool classrooms have suggested can rate the models’ conversational child linguistic interaction in integrated

that these strategies occur less frequent- day care groups. Language, Speech, and

responsiveness. Alternatively, adults

Hearing Services in Schools, 31, 155-168.

ly than is desirable (e.g., Girolametto, can watch themselves interacting with Girolametto, L., & Weitzman, E. (2002).

Hoaken, Weitzman, & van Leishout, the children in their own classrooms to Responsiveness of child care providers in

evaluate their own strengths and needs interactions with toddlers and preschool-

ers. Language, Speech, and Hearing

in using specific language-stimulation

Services in Schools, 33, 268-281.

This process-oriented strategies. Girolametto, L., Weitzman, E., & Greenberg,

approach provides a Final Thoughts

J. (2003). Training day care staff to facili-

tate children’s language. American

framework for ensuring Building preschool programs that pro- Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12,

vide language-rich classroom environ- 299-311.

that preschool children ments is a complex and multidimen- Hallahan, D. P., & Kaufman, J. M. (2003).

Exceptional learners (9th ed.). Boston,

have the language-rich sional process. Although many educa- MA: Allyn and Bacon.

tors, policymakers, and parents are Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful

classroom environments

aware of specific qualities of language- differences in the everyday experience of

that are most beneficial to rich classrooms, putting this knowledge young American children. Baltimore: Paul

Brookes.

to work takes considerable effort. This

their early development. Hoff, E. (2003). The specificity of environ-

article describes a five-step team-based mental influence: Socioeconomic status

process for designing and implementing affects early vocabulary development via

language-rich classroom environments maternal speech. Child Development, 74,

for preschool classrooms. The team- 1368-1378.

2000). Teams therefore must schedule Justice, L. M., & Ezell, H. K. (1999).

based action plan involves identifying a

sessions to practice these strategies with Vygotskian theory and its application to

team, developing a philosophy, design- language assessment: An overview for

one another, and team members should

ing the physical space, designing daily speech-language pathologists. Contempo-

mentor one another in the classroom in

language plans, and ensuring quality rary Issues in Communication Science and

quality implementation of these strate- Disorders, 26, 111-118.

gies. A salient approach to improving adult-child conversations. This process-

Justice, L. M., & Kaderavek, L. M. (2002).

adult behaviors when interacting with oriented approach provides a frame- Using shared book reading to promote

children is through observational learn- work for ensuring that preschool chil- emergent literacy. TEACHING Exceptional

dren have the language-rich classroom Children, 34, 8-13.

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ NOV/DEC 2004 ■ 43

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

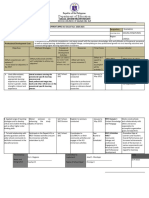

Table 4. Language Stimulation Techniques Rush, K. L. (1999). Caregiver-child interac-

tions and early literacy development of

Technique Description preschool children from low-income envi-

ronments. Topics in Early Childhood

Waiting Adult uses a slow pace during conversa-

Special Education, 19, 3-14.

tion; adult actively listens to children when Smith, M., & Dickinson, D. (2002). Early lan-

talking; adult does not dominate conver- guage and literacy classroom observation

sation. toolkit. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Snow, C., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (Eds.).

Pausing Adult pauses expectantly and frequently (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in

during interactions with children to young children. Washington, DC: National

encourage their turn-taking and active Academy Press.

participation. Taylor, N. E., Blum, I. H., & Logsdon, D. M.

(1986). The development of written lan-

Confirming Adult responds to all child utterances by guage awareness: Environmental aspects

confirming understanding of the child's and program characteristics. Reading

intentions. Adult does not ignore child Research Quarterly, 21, 132-149.

van Kleeck, A., Gillam, R. B., Hamilton, L., &

communicative bids. McGrath, C. (1997). The relationship

Imitating Adult imitates and repeats what child says between middle-class parents’ book-shar-

ing discussion and their preschoolers’

more or less exactly. Example: Child: I did

abstract language development. Journal of

the puzzle. Adult: You did the puzzle. Speech, Language, and Hearing Research,

40, 1261-1271.

Extending Adult repeats what child says and adds a

small amount of syntactic or semantic Laura M. Justice, Assistant Professor,

information. Example: Child: I did the McGuffey Reading Center and Director,

puzzle. Adult: You did the puzzle well. Preschool Language and Literacy Lab,

University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Labeling Adult provides the labels for familiar and

unfamiliar actions, objects, or abstrac- Address correspondence to Laura M. Justice,

Preschool Language and Literacy Lab,

tions (e.g., feelings).

University of Virginia, Box 400873,

Charlottesville, VA 22904 (e-mail: ljustice@

Open questioning Adult asks questions to which he or she

virginia.edu).

does not know the answer; these include

some what, where, and when questions TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 37,

(e.g., What are you going to do now?), No. 2, pp 36-44.

as well as how and why questions. Copyright 2004 CEC.

Scripting Adult provides a routine to the child for

representing an activity (e.g., First, you

go up to the counter. Then you say, "I

want a hamburger…") and engages the

Ad Index

child in known routines (e.g., "Now it is

time for circle time. What do we do AGS—KTEA II, p 27

first?"). Council for Exceptional

Children, p 21, 45, 59, 60, 61,

For additional descriptions of these and other language stimulation techniques, see

66

Bunce (1995) and Girolametto and Weitzman (2002).

Crisis Prevention Institute,

cover 3

Landry, S. H., Miller-Loncar, C. L., Smith, K. (Eds.), Building a language-focused cur- Curriculum Associates, p 1

E., & Swank, P. R. (1997). Predicting cog- riculum for the preschool classroom (Vol. LR Consulting, p 14

nitive-language and social growth curves 1; pp. 155-169), Baltimore, MD: Paul. H.

from early maternal behaviors in children Brookes.

Mayer Educational Products,

at varying degrees of biological risk. Robbins, C., & Ehri, L. C. (1994). Reading p 35

Developmental Psychology, 33, 1040-1053. storybooks to kindergarteners helps them NASCO, p 14

Penno, J. F., Wilkinson, I. A., & Moore, D. W. learn new vocabulary words. Journal of

Penn State University, cover 2

(2002). Vocabulary acquisition from Educational Psychology, 86, 54-64.

teacher explanation and repeated listening Roskos, K., & Neuman, S. B. (2002). Riverside Publishing, p 30,

to stories: Do they overcome the Matthew Environment and its influences for early cover 4

effect? Journal of Educational Psychology, literacy teaching and learning. In S. B. Ten Sigma, p 34

94, 23-33. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.),

Rice, M. L., & Hadley, P. (1995). Language Handbook of early literacy research (pp.

outcomes of the language-focused cur- 281-294). New York: The Guilford Press.

riculum. In M. L. Rice & K. A. Wilcox

44 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at DALHOUSIE UNIV on June 5, 2016

You might also like

- Activity 06 - Curriculum DevelopmentDocument1 pageActivity 06 - Curriculum DevelopmentJoesa AlfanteNo ratings yet

- Session 5Document25 pagesSession 5Crisel GonowonNo ratings yet

- Action Plan: Republic of The Philippines Department of EducationDocument6 pagesAction Plan: Republic of The Philippines Department of EducationSarghuna RaoNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesJojam Carpio100% (1)

- Strategic DirectionDocument2 pagesStrategic Directiongiacara.partosaNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Individual Development PlanDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Individual Development PlanMark Jim ToreroNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesBernardoNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Action Plan in Mother TongueDocument6 pagesDepartment of Education: Action Plan in Mother TongueMary Eilleen CabralNo ratings yet

- Action Plan For Cerebral Palsy and Down SyndromeDocument3 pagesAction Plan For Cerebral Palsy and Down SyndromeGheylhu Amor0% (1)

- Individual Development PlanDocument3 pagesIndividual Development PlanZesa S. BulabosNo ratings yet

- English Reading ProposalDocument3 pagesEnglish Reading ProposalJenny Canoneo GetizoNo ratings yet

- Reading Intervention Plan - : 75% by The End of The School Year As Measured by The DIV IRI AdministeredDocument3 pagesReading Intervention Plan - : 75% by The End of The School Year As Measured by The DIV IRI AdministeredDecember CoolNo ratings yet

- Action Plan RREDocument2 pagesAction Plan RREJUDITH APOSTOLNo ratings yet

- Course 3Document41 pagesCourse 3Leilani BacayNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment Report June 8-12, 2020Document2 pagesAccomplishment Report June 8-12, 2020MoxyNo ratings yet

- Individual Professional Development Plan (Ipdp) : Republic of The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesIndividual Professional Development Plan (Ipdp) : Republic of The Philippineswaltz crisNo ratings yet

- IPPDDocument2 pagesIPPDJordan Ven BaculioNo ratings yet

- Destanee Cruz ResumeDocument3 pagesDestanee Cruz Resumeapi-456833206No ratings yet

- Action Plan Primary DepartmentDocument6 pagesAction Plan Primary DepartmentInes VergaraNo ratings yet

- Chart: Update of Action Plan: A: PhilosophyDocument11 pagesChart: Update of Action Plan: A: Philosophyapi-353859154100% (3)

- Developmental Plans of The IpcrfDocument4 pagesDevelopmental Plans of The IpcrfLester VillosoNo ratings yet

- 2 AS AnglaisDocument33 pages2 AS AnglaisLarbi NadiaNo ratings yet

- Action Plan: Republic of The Philippines Department of EducationDocument6 pagesAction Plan: Republic of The Philippines Department of EducationSarghuna RaoNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesEdlyn KayNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Teaching and Assessment of TheDocument12 pagesSyllabus Teaching and Assessment of TheJoseph BrocalNo ratings yet

- Ippd Form 1 - Teacher'S Individual Plan For Professional Development (Ippd) SY 2021-2022Document1 pageIppd Form 1 - Teacher'S Individual Plan For Professional Development (Ippd) SY 2021-2022Lea CardinezNo ratings yet

- Pre-Implementation Phase Strategies Action Persons Involved Budget Time Frame Expected OutputDocument10 pagesPre-Implementation Phase Strategies Action Persons Involved Budget Time Frame Expected OutputNederysiad ManuelNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument42 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesXander1222100% (2)

- Amaro - Overview Table Spring 2019Document3 pagesAmaro - Overview Table Spring 2019api-457764841No ratings yet

- KPS Business Plan 2021 2024Document2 pagesKPS Business Plan 2021 2024tamNo ratings yet

- Teachers Action Plan CoordinatorDocument4 pagesTeachers Action Plan CoordinatorMarie Joy PepitoNo ratings yet

- KidzeeDocument16 pagesKidzeeXLS OfficeNo ratings yet

- Guadalupe Gonzalez Nunans1&2Document2 pagesGuadalupe Gonzalez Nunans1&2Himitsu Yuki CrosszeriaNo ratings yet

- Whole Language PhilosophyDocument4 pagesWhole Language PhilosophySMART COPYNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The Philippinesmuhajirin b sali100% (2)

- Individual Professional Development Plan (Ipdp) : Republic of The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesIndividual Professional Development Plan (Ipdp) : Republic of The Philippineswaltz crisNo ratings yet

- Individual Professional Development Plan (Ipdp) : Republic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesIndividual Professional Development Plan (Ipdp) : Republic of The Philippineswaltz crisNo ratings yet

- Be-Lcp Best Implementation Paps Implementation Measures Risks/ Challenges/ Gaps Encountered Contingency MeasuresDocument3 pagesBe-Lcp Best Implementation Paps Implementation Measures Risks/ Challenges/ Gaps Encountered Contingency MeasuresLeah May Diane CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Ed498 Inquiry ProjectDocument6 pagesEd498 Inquiry Projectapi-481557125No ratings yet

- IPPDDocument2 pagesIPPDvic degamoNo ratings yet

- Planned For Enriched Teaching PracticeDocument2 pagesPlanned For Enriched Teaching PracticeCharisma SorianoNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesKhrisOmz PenamanteNo ratings yet

- RPMS SY 2021-2022: Teacher Reflection Form (TRF)Document7 pagesRPMS SY 2021-2022: Teacher Reflection Form (TRF)EDEN SOL GERONGANo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesKhrisOmz Penamante50% (2)

- Full-Day Early Learning Kindergarten Program: For Four-And Five-Year-OldsDocument15 pagesFull-Day Early Learning Kindergarten Program: For Four-And Five-Year-OldsDyadytaNo ratings yet

- English Action Plan 2021 2022Document2 pagesEnglish Action Plan 2021 2022Jonefer Nazareno Paran100% (1)

- NFPS Strategic PlanDocument2 pagesNFPS Strategic PlanNorth Fremantle Primary SchoolNo ratings yet

- Action Plan GADDocument2 pagesAction Plan GADJaja Carlina100% (1)

- Annual Learning Action Cell (Lac) Plan Sy 2019-2020Document10 pagesAnnual Learning Action Cell (Lac) Plan Sy 2019-2020Gil Marcelo100% (1)

- Action Plan in EnglishDocument3 pagesAction Plan in EnglishBernard Mae S. LasanNo ratings yet

- Sowing Seeds of SelDocument5 pagesSowing Seeds of SelFrancisco DeceanoNo ratings yet

- School Action Plan On LDM ReadinessDocument3 pagesSchool Action Plan On LDM ReadinessALICIA ROSALES100% (3)

- Action Plan For GddidDocument6 pagesAction Plan For GddidGheylhu AmorNo ratings yet

- WTG PB5 Sample U8Document12 pagesWTG PB5 Sample U8Elijah BayleyNo ratings yet

- Individual Development Plan: A. Functional Competencies 1. Content Knowledge and PedagogyDocument3 pagesIndividual Development Plan: A. Functional Competencies 1. Content Knowledge and PedagogyBlu MarlenesNo ratings yet

- Provision For Accessible Support System: Project PASSDocument4 pagesProvision For Accessible Support System: Project PASSAmeriza Purpura Tena - CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- Activity Methods - METHODOLOGY IDocument6 pagesActivity Methods - METHODOLOGY IGabby TituañaNo ratings yet

- Master Teacher Developmental Plan Real2021 2022Document6 pagesMaster Teacher Developmental Plan Real2021 2022Roygvib Clemente MontañoNo ratings yet

- Fresno PLI Analytics Report Year 1 2017Document13 pagesFresno PLI Analytics Report Year 1 2017إريكا أنوغرا هينيNo ratings yet

- A Review of English Teaching Practices in The Philippines: January 2016Document8 pagesA Review of English Teaching Practices in The Philippines: January 2016brutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- 74352632Document99 pages74352632leonel gavilanesNo ratings yet

- Improving EFL Students' Speaking Proficiency and Motivation: A Hybrid Problem-Based Learning ApproachDocument12 pagesImproving EFL Students' Speaking Proficiency and Motivation: A Hybrid Problem-Based Learning ApproachbrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- How Do Teachers Talk About Oral Proficiency in The English C/7' Course? A Qualitative StudyDocument41 pagesHow Do Teachers Talk About Oral Proficiency in The English C/7' Course? A Qualitative StudybrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- The Role of Teachers in Developing Learners' Speaking Skill: April 2015Document18 pagesThe Role of Teachers in Developing Learners' Speaking Skill: April 2015brutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- How 2 Improve English LanguageDocument37 pagesHow 2 Improve English Languagespica_shie88No ratings yet

- Mapeh Club Tiktok Dance Challenge 4Document1 pageMapeh Club Tiktok Dance Challenge 4brutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- Developing and Testing EVALOE: A Tool For Assessing Spoken Language Teaching and Learning in The ClassroomDocument18 pagesDeveloping and Testing EVALOE: A Tool For Assessing Spoken Language Teaching and Learning in The ClassroombrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- Rubric For Scoring Dance Performance EvaluationDocument3 pagesRubric For Scoring Dance Performance EvaluationRose Ann M. Alvarez100% (1)

- Burnkart Spoken Language What It Is and How To Teach It PDFDocument34 pagesBurnkart Spoken Language What It Is and How To Teach It PDFifdol pentagenNo ratings yet

- The Direct-Method A Good Start To Teach Oral LanguageDocument3 pagesThe Direct-Method A Good Start To Teach Oral Languageapi-274380027No ratings yet

- Teaching The Spoken Text TypesDocument1 pageTeaching The Spoken Text TypesbrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- Ivor Timmis: 2012 XX XXDocument9 pagesIvor Timmis: 2012 XX XXbrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- Towards A Framework For Teaching Spoken Grammar: Ivor TimmisDocument9 pagesTowards A Framework For Teaching Spoken Grammar: Ivor TimmisbrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- December 2008 EbookDocument248 pagesDecember 2008 EbookfadulliNo ratings yet

- THE COMPUTER AS A TUTOR - Trisha Guira and Jocel Ann SegundoDocument3 pagesTHE COMPUTER AS A TUTOR - Trisha Guira and Jocel Ann SegundobrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- Music6 - q1 - Mod2 - Rhythm Differentiate Time Signatures - FINAL08032020 PDFDocument35 pagesMusic6 - q1 - Mod2 - Rhythm Differentiate Time Signatures - FINAL08032020 PDFbernadette embien68% (25)

- Curriculum ModDocument3 pagesCurriculum ModbrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Instruction: Creating An Authentic Learning Environment in The Foreign Language ClassroomDocument14 pagesInternational Journal of Instruction: Creating An Authentic Learning Environment in The Foreign Language ClassroombrutedeepaxNo ratings yet

- Computer As The Teacher's ToolDocument5 pagesComputer As The Teacher's Toolbrutedeepax0% (1)

- Introduction To Young Children With Special Needs Birth Through Age Eight 4th Edition Gargiulo Solutions ManualDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Young Children With Special Needs Birth Through Age Eight 4th Edition Gargiulo Solutions ManualKyleTaylorkgqoy100% (18)

- The Guide - Winter 2016Document28 pagesThe Guide - Winter 2016The Grove ChurchNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Education (Ece)Document20 pagesEarly Childhood Education (Ece)Zeeshan Abdullah100% (1)

- Government of Kerala: Nursery Teachers Education Course Examination MARCH 2013Document11 pagesGovernment of Kerala: Nursery Teachers Education Course Examination MARCH 2013edujobnewsNo ratings yet

- The Real Reason Why TV Is Bad For The KidsDocument2 pagesThe Real Reason Why TV Is Bad For The Kidstyas andriastutiNo ratings yet

- Outdoor Play Zero To ThreeDocument5 pagesOutdoor Play Zero To ThreeINSTITUTO ALANANo ratings yet

- China Poverty 2011Document33 pagesChina Poverty 2011solikearoseNo ratings yet

- Moe BlueprintsDocument192 pagesMoe BlueprintsAmirul AmzarNo ratings yet

- NISA Early Learning InitiativesDocument3 pagesNISA Early Learning Initiatives陈海旭No ratings yet

- PS Early Childhood Education PDFDocument69 pagesPS Early Childhood Education PDFHanafi MamatNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning English in Kindergartens in Kaohsiung: by Mei-Ling ChuangDocument241 pagesTeaching and Learning English in Kindergartens in Kaohsiung: by Mei-Ling ChuanglinguistAiaaNo ratings yet

- Bedtime Routines For Young ChildrenDocument6 pagesBedtime Routines For Young ChildrenmithaNo ratings yet

- Monthly Newsletter 09-2012Document8 pagesMonthly Newsletter 09-2012Brittany WilligNo ratings yet

- Ram BookDocument52 pagesRam BookRobson FletcherNo ratings yet

- Preschool Planning Guide: Building A Foundation For Development of Language and Literacy in The Early YearsDocument29 pagesPreschool Planning Guide: Building A Foundation For Development of Language and Literacy in The Early YearsPedro GandollaNo ratings yet

- Basic ESL Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesBasic ESL Lesson PlanNortheagleNo ratings yet

- The Aims of The Enhanced K12 orDocument9 pagesThe Aims of The Enhanced K12 orNoly TicsayNo ratings yet

- Amanda: KocimskiDocument2 pagesAmanda: Kocimskiapi-340930763No ratings yet

- Writing Project ProposalDocument22 pagesWriting Project ProposalMamin Chan0% (1)

- Status of Education in SwedenDocument5 pagesStatus of Education in Swedenapi-278303622No ratings yet

- Shaking The Foundations of Quality (Nutbrown) 18th March 2013Document10 pagesShaking The Foundations of Quality (Nutbrown) 18th March 2013Laura HenryNo ratings yet

- Keshava Seva Samithi BrochureDocument2 pagesKeshava Seva Samithi Brochurekappi4uNo ratings yet

- WEEKLY Supervisory PLANDocument5 pagesWEEKLY Supervisory PLANLeodigaria Reyno100% (3)

- Power Student OlympicsDocument111 pagesPower Student OlympicsGeorge WhiteheadNo ratings yet

- Anya Manolakas Updated ResumeDocument2 pagesAnya Manolakas Updated Resumeapi-374878857No ratings yet

- PediatricDocument4 pagesPediatricIrma Nur Rizka HanifahNo ratings yet

- When Business " Adopts" Schools: Spare The Rod, Spoil The Child, Cato Policy AnalysisDocument11 pagesWhen Business " Adopts" Schools: Spare The Rod, Spoil The Child, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Resume 5 27 15Document2 pagesResume 5 27 15api-280297546No ratings yet

- Valley Viewer Sept 14 FullDocument48 pagesValley Viewer Sept 14 FullOssekeagNo ratings yet

- University Day Care CenterDocument6 pagesUniversity Day Care CenterLily HellingsNo ratings yet