Professional Documents

Culture Documents

South East Asian Institute of Technology, Inc. National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South Cotabato

Uploaded by

Christian BañaresOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

South East Asian Institute of Technology, Inc. National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South Cotabato

Uploaded by

Christian BañaresCopyright:

Available Formats

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South Cotabato

COLLEGE OF TEACHER EDUCATION

___________________________________________________

LEARNING MODULE

FOR

EDUC 311: FOUNDATION OF SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

_____________________________________________________

WEEK 13

_______________________

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 1 of 27

COURSE OUTLINE

COURSE CODE : EDUC 311

TITLE : Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

TARGET POPULATION : 3rd Year students

INSTRUCTOR : MS. MARY GRACE ABAYON

Overview:

This course shall deal with philosophies, theories and legal bases of special needs and inclusive

education, typical and atypical development of children, learning characteristics of students with special

educational needs (gifted and talented, learners with difficulty hearing, learners with difficulty

communicating, learners with difficulty walking/moving, learners with difficulty remembering and focusing,

learner with difficulty with self-care) and strategies in teaching and managing these learners in regular class.

General Objective

To understand the historical, philosophical beliefs, and the barriers to accessibility and acceptance

of individuals with exceptionalities.

The following are the topics to be discussed

Week 13 PRACTICAL STRATEGIES FOR SUPPORTING AND TEACHING CHILDREN

WITH SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS AND DISABILITIES

Week 14-15 SCHOOL EXPERIENCE

Week 16 THE ROLE OF THE SENDCO

Week 17 SKILLS FOR COLLABORTING WITH PROFESSIONALS AND PARENTS

Instruction to the Learners

This course is designed to introduce the beginning graduate student to the field of special education.

The course material is intended to provide students with an overview of the historical and legal practices,

professional and the ethical issues that are needed to provide all students with exceptionalities with an

effective education, advocacy and supports. The units are characterized by continuity, and are arranged in

such a manner that the present unit is related to the next unit.

Students are required to set up a course resource handbook- a portfolio of ideas, sources, and cross-

references that may be useful to you in your later teaching career. For this reason, you are advised to read

this module. After each unit, there are task and exercises given. Submission of the first activity will be on

DECEMBER 18 (SATURDAY), 2021 and for the remaining activities will be on JANUARY 8 (SATURDAY),

2020. Late submission of activities will be deducted 5-points per day.

Overview of the Exceptionalities Resource Handbook

Your final draft of your course resource handbook will be submitted on the given time frame of the

instructor. While this activity may seem daunting at first, please realize that if it is done correctly, the portfolio

will be an excellent, critical resource for you in the future. It is strongly recommended that you DO NOT wait

until close to the due date to begin the activity. For this reason, you are advised to read this module. After

each unit, there are exercises to be given. Submission of task given will be every Tuesday during your

scheduled class hour.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 2 of 27

WEEK 13

LEARNERS WITH ADDITIONAL NEEDS

I. LEARNERS WHO ARE GIFTED AND TALENTED

A. Definition

Learners who are gifted and talented are students with higher abilities than average and are

often referred to as gifted students. This group refers to students whose talents, abilities, and

potentials are developmentally advanced. They require special provisions to meet their educational

needs, thus presenting a unique challenge to teachers. They often finish tasks ahead and might ask

for more creative tasks or exercises. Exciting

and energizing activities should be provided to

continuously keep them motivated. This group

includes students with exceptional abilities from

all socio-economic, ethnic, and cultural

populations. What is the difference then

between gifted and talented? The term

giftedness refers to students with extraordinary

abilities in various academic areas. However,

talent focuses on students with extraordinary

abilities in a specific area.

There is also another way to look into giftedness

which is conceptualized by Gardner in 1993.

According to him, intelligence is multifaceted.

The following intelligences are seen in Figure

6.1.

B. Identification

To identify gifted and talented students, one

must do the following:

Locate the student’s domain of giftedness

Describe the student’s level of giftedness

Describe the student’s fields of talent

C. Learning Characteristics

Not all learners will exhibit the learning characteristics listed below. However, these are the

common manifestations of gifted and talented learners. One might possess a combination of

characteristics in varying degrees and amounts.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 3 of 27

High Level of intellectual curiosity

Reads actively

High degree of task commitment

Keep power of observation

Highly Verbal

Gets bored easily

Can retain and recall information

Excited about learning new concepts

Independence in learning

Good Comprehension of complex contexts

Strong, well-developed imagination

Looks for new ways to do things

Often gives uncommon responses to common questions

D. General Educational Adaptations

Learners who are gifted and talented usually get bored since they have mastered the concepts

taught in classes. One thing that is common among gifted students is that they are very inquisitive.

Fulfilling their instructional needs may be a challenging task. These are some suggested strategies

for teaching gifted students:

Teachers may give enrichment exercises that will allow learners to study the same topic at a

more advanced level.

Acceleration can let students who are gifted and talented can move at their own pace thus

resulting at times to in completing two grade levels in one school year.

Open-ended activities with no right or wrong answers can be provided, emphasizing on

divergent thinking wherein there are more possibilities than pre-determined answers.

Leadership roles can be given to gifted students since studies have shown that gifted

students are often socially immature.

Extensive reading on subjects of their own interest may be coordinated with the school

librarian to further broaden their knowledge.

Long-term activities may be provided, that will give the gifted students an opportunity to be

engaged for an extended period of time.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 4 of 27

II. LEARNERS WITH DIFFICULTY SEEING

A. Definition

Students in the classroom will exhibit different levels of clarity of eyesight or visual acuity. There

may be some students with hampered or restricted vision. Learners with difficulty seeing are those

with issues regarding sight that interfere with academics. The definition from Individuals with

Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) states that “an impairment in vision that, even with correction,

adversely affects a child’s educational performance, which includes both partial sight and blindness.”

These students may need to have their eyesight corrected by wearing glasses or other optical

devices.

B. Identification

Learners with difficulty seeing often have physical signs, such as crossed eyes, squinting, and

eyes that turn outwards. They may also be clumsy, usually bumping into objects which causes them

to fall down. They like to sit near the instructional materials or at times would stand up and go near

the visual aids.

Learners with difficulty seeing may also show poor eye-hand coordination. This can be seen in

their handwriting or poor performance in sporting activities. Another indication is poor academic

performance as these students might have difficulty reading as well as writing.

C. Learning Characteristics

Good visual ability is critical in learning. Most school lessons are done through blackboard

writing, presentations, or handouts, in most major subjects. Visual impairments, whether mild,

moderate, or severe, affect the student’s ability to participate in normal classroom activities. In the

past, students who are visually impaired are placed in special institutions. Nowadays, most are

enrolled with other children who are not visually impaired.

Learners with difficulty seeing have restricted ways to learn incidentally from their surroundings

since most of them learn through visual clues. Because of this, the other senses are used to acquire

knowledge. Due to the limited ability to explore the environment, low motivation to discover is

present.

D. General Educational Adaptations

Modification in teaching is needed to accommodate students with difficulty seeing. The following

strategies may be considered:

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 5 of 27

If the use of books is part of your lesson, students with difficulty seeing should be

informed ahead of time so that they c can be ordered in braille or in an audio recorded

format.

Portions of textbooks and other printed materials may be recorded so that visually-

impaired students can listen instead of focusing on the visual presentation.

All words written on the board should be read clearly.

Students with difficulty seeing should be seated near the board so that they can easily

move close to the instructional materials used during the lesson.

A buddy can be assigned to a student with difficulty seeing as needed. This can be crucial

to assist in the mobility of the student such as going to the other places in school] during

the day.

Students with difficulty seeing might need more time to complete a task or homework.

This might be on a case to case basis.

Teachers should be aware of terminology that would require visual acuity (such as over

there or like this one) which the impaired student may not possess.

Teachers should monitor the students closely to know who needs extra time in completing

tasks.

III. LEARNERS WITH DIFFICULTY HEARING

A. Definition

This refers to students with an issue regarding hearing that interferes with academics. The

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 6 of 27

definition from Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) defines it as “an impairment in

hearing, whether permanent or fluctuating, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance

but is not included under the definition of ‘deafness’.” Deafness is considered when hearing loss is

above 90 decibels. A hearing loss below 90 decibels is called hearing impairment.

The main challenge of hearing-impaired students is communication, since most of them have

varying ways of communicating. The factors affecting the development of communication skills

include intelligence, personality, the degree and nature of deafness and residual hearing, family

environment, and the age onset. The latter plays the most hearing loss present at birth are more

functionally disabled than those hearing after language and speech development.

B. Identification

To identify learners with difficulty hearing, observe a student and see if he/she does the following

items below.

Speaking loudly

Positioning ear toward the direction of the one speaking ° Asking for information to be

repeated again and again

Delayed development of speech

Watching the face of the speaker intently

Favoring one ear

Not responding when called

Has difficulty following directions

Does not mind loud noises

Leaning close to the source of sounds

C. Learning Characteristics

Since much of learning is acquired through hearing, students with hearing problems have

deficiencies in language and in their experiences. Since they may miss out on daily conversations,

they may miss crucial information that non-hearing-impaired students learn incidentally. Students

may overcome these problems by investing time, energy, and combined effort by both parents and

educators.

Most learners with difficulty hearing use various methods of communication. The most common

is the use of hearing aids, combined with lip-reading. These students are referred to as “oral” since

they can communicate thru speech as opposed to sign language. They might have delayed

communication skills since the development of vocabulary is slower. They understand concepts

when the sentence structure is simpler. Interacting with students can be a challenge so they prefer

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 7 of 27

to work on their own. Some hearing-impaired students use note-takers in class since it is difficult to

lip-read and take notes simultaneously.

D. General Educational Adaptations

There is an assumption that the only adjustment for hearing impaired students is to make all

instructional materials and techniques in written format. These are other ways to adapt to

hearing-impaired students;

Teachers should help students with difficulty hearing to use the residual hearing they may

have.

Teachers should help students develop the ability for speech reading or watching others’ lips,

mouth, and expressions.

Teachers should be mindful to face the class at all times when presenting information while

ensuring that the students with difficulty hearing sit near them.

Exaggerating the pronunciation of words should not be done for it just makes it difficult for the

student with difficulty hearing.

Directions, as well as important parts of the lesson, should always be written on the board.

Written or pictorial directions instead of verbal directions may be given.

Steps to an activity may be physically acted out instead of verbally given.

A variety of multi-sensory activities should be given to allow the students to focus on their

learning strengths.

Teachers should be more patient when waiting to hear a response from a hearing-impaired

student which may take longer than usual.

LEARNERS WITH ADDITIONAL NEEDS

IV. LEARNERS WITH DIFFICULTY COMMUNICATING

Some learners are observed to have difficulty communicating, either verbally expressing their

ideas and needs and/or in understanding what others are saying. Some may have had a clinical

diagnosis of a disability while others display developmental delays and difficulty in the speech and

language domain.

To have a clearer understanding of students who have difficulty communicating, We will begin

with a definition of communication and its accompanying concepts; how learners with

communications difficulties are identified, their learning characteristics, and ways how to help them

manage and become successful in an inclusive setting.

A. Definition: Types of Communication Impairments and Disorders

Communication is the interactive exchange of information, ideas, feelings, needs, and desires

between and among people (Heward, 2013). Communication is used to serve several functions,

particularly to narrate, explain, inform, request (mand), and express feelings and opinions.

How is speech different from language?

Speech is the expression of language with sounds, or oral production. Speech is produced through

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 8 of 27

precise physiological and neuromuscular coordination: (1) respiration (act of breathing), (2)

phonation (production of sound by the larynx and vocal folds), and (3) articulation (use of lips,

tongue, teeth, and hard and soft palates to speak).

Language is used for communication, a forrnalized code used by a group of people to communicate

with one another, that is primarily arbitrary (Heward, 2013). People decide on symbols, their

corresponding meaning, and rules that make up a language. There are five dimensions of language

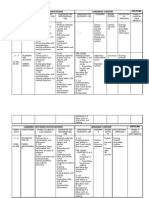

that describe its form (i.e., phonology, morphology, syntax, content, and use (pragmatics). Table 6.1

provides a description for each dimension.

Table 6.1 Components of Language

Components Description

Phonology Phonology refers to the sound system of a language. A phoneme is the smallest

unit of sound within a language. For instance, the word dog is made up of three

phonemes, namely /d/-/o/-/g/ while beans has four phonemes, /b/-/e/-/a/-/n/-/s/.

Morphology Morphology of a language refers to the smallest unit of language that had

meaning and which are used to combine words. Sounds, syllable, or whole

words are examples of morphemes.

Syntax Syntax is the system of rules governing the meaningful arrangement of words,

which also include grammar rules. For instance, the sentence, Ready get for the

exam does not make sense until arrange in the right sequences as Get ready for

the exam.

Semantics Semantics refers to the meanings associated with words and combination of

words in a language. This also includes vocabulary, concept development,

connotative meanings of words, and categories.

Pragmatics Pragmatics revolves around the social use of language, knowing what, when,

and how to communicate and use language in specific context. There are three

kinds of pragmatic skills: (1) using language for different purposes (e.g.,

narrating, explaining, requesting, etc.), (2) changing language according to the

context (e.g., talking to a peer as compared to speaking to a well-respected

professor), and (3) following rules for conversations and story-telling (e.g., taking

turns, rephrasing when unclear, how to use facial expressions and eye contact,

etc.) (America Speech-Language Hearing Association, 2011 cited in Heward,

2013).

Knowing these terms is necessary to understand the different disabilities that are associated

with communication disorders, namely Speech Impairments and Language Disorders.

Speech Impairments are communication disorders such as stuttering, impaired articulation, and

language or voice impairment. Such disorders are significant enough that they can adversely affect

a student’s academic performance. There are four basic types of speech impairments: articulation,

phonological, fluency, and voice disorder (see Table 6.2).

Speech impairment Description Examples

Articulation Disorder A child is unable to produce a “I want a blue lollipop.”

given sound physically. Severe

articulation disorder may render a “I want a boo wowipop.”

child’s speech unintelligible.

“Can I get three bananas?”

Examples are substitutions,

omissions, distortions of speech An I et tee nanas?”

sounds.

Phonological Disorder A child produces multiple patterns “That pie is good.”

of sound errors with obvious

impairment of ntelligibility. There is “Cat by is tood.”

also noted inconsistent

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 9 of 27

misarticulation of sounds (i.e.,

sometimes a child is able to

articulate it but not in other words).

Fluency Disorder Difficulties with the rhythm and Blocks:

timing of speech. Stuttering is an

example marked by rapid-fire “I want a… banana.”

repetitions of consonant or vowel

(blocks)

sound especially at the beginning

of words, prolongations, Prolongations

hesitations, interjections, and

complete verbal blocks (Ramig “I waaaant a bbbanana.”

&Sahames, 2006 cited in Gargiulo

2012). Repititions

“I want a ba-ba-ba-banana.”

Voice disorder Problems with the quality or use of Phonation disorder

one’s voice resulting from

disorders of the larynx. Voice may (breathiness, hoarseness)

be excessively hoarse, breathy, or

Hypernasality

too high-pitched.

Hyponasality

Language Disorders involve problems in one or more of the five components of language and are often

classified as expressive or receptive. Language disorders are characterized by persistent difficulties in

acquiring use of language that result from deficits in comprehension that include reduced vocabulary, limited

sentence structure, impairments in discourse, that limit a child’s functioning (American Psychiatric

Association 2013). To receive a diagnosis of language disorder, the difficulties must not be due to an

accompanying medical or neurological condition and other developmental disability (i.e., intellectual

disability or global developmental delay).

There are different types of language disorder-expressive, receptive, and a combination of the two. An

expressive language disorder interferes with the production of language. A child may have very limited

vocabulary that impacts communication skills or misuses words and phrases in sentences. On the other

hand, a receptive language disorder interferes with the understanding of language. A child may have

difficulty understanding spoken sentences or following the directions a teacher gives. Some children may be

found to have a combination of receptive and expressive language disorder.

ACTIVITY 13

Discussion Points and Exercise Questions

Direction: Read and understand this module. Provide what is being asked.

TASKS:

1. Create a 4A’s detailed lesson plan that shows useful activity appropriate for a student with specific

learning disabilities (write it on a long bond paper). Then, record yourself and submit it through

messenger along with the picture of your lesson plan.

CRITERIA:

Delivery 30

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 10 of 27

Mastery 20

Lesson Plan 30

Application and congruence of instructional materials 20

TOTAL 100

End of 13th Week

---------------------------------------Nothing Follows-------------------------------------

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 11 of 27

National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South Cotabato

COLLEGE OF TEACHER EDUCATION

___________________________________________________

LEARNING MODULE

FOR

EDUC 311: FOUNDATION OF SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

_____________________________________________________

WEEK 14-15

____________________

WEEK 14-15

SCHOOL EXPERIENCE

INTRODUCTION

School experience in a special needs provision can be exciting, enlightening and rewarding. It can

challenge many ideas and beliefs you may already hold, and for some it can shape future career decisions.

It can, however give rise to anxiety and trepidation, often due to an unavoidable lack of experience or

knowledge. But with guidance and support from both your teacher education provider and special needs

provider, you can gain pedagogical skills which are transferable in both special and mainstream setting, as

good-quality teaching is essential, and valuable intersections between special and mainstream education

must not be missed (Cochran-Smith and Villegas, 2016: 439).

This chapter aims to give a practical, rather than a theoretical overview of your placement, as the theory

should have been covered by your teacher education provider. On the other hand, trainees often feel that

they need information and guidance on the practical experience of their placement to include opportunities

to:

learn skills and approaches that are not

exclusive to special provision but can enhance

all aspects of teaching and learning;

learn about the wide range of professionals

involved in specialist provision and the

importance of tem working;

Try out new approaches and be able to accept

that outcomes are not always predictable and

that behavior

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Educationcan play a big part in this;

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 12 of 27

link theory to practice to enhance professional

development.

THE THEORY BEHIND THE PRACTICE

The Code of Practice covers children and young people from 0 to 25 years, to facilitate successful

transitions, with greater emphasis on obtaining the views of children and young people, especially in

decision-making processes. There is a greater focus on multi-agency collaboration between education,

health and social care services, (Dfe, 2015).

FOCUS ON PRACTICE

The main objective of this chapter is to help you put theory into practice, to understand the practical

implications associated with a short placement in a special school setting, and to fulfill the Teacher’s

Standards.

UNDERSTANDING INCLUSIVE PRACTICE

Inclusion on education involves:

Valuing all students and staff equality;

Increasing the participation of students in, and reducing their exclusion from the cultures, curricula

and communities of local schools;

Restructuring the cultures, policies and practices in schools so that they are more responsive to the

diverse needs of their students;

Reducing barriers to learning and participation for all students, not only those with impairments or

those who are categorized as ‘having special educational needs’;

Learning from attempts to overcome barriers to the access and participation of particular students to

make changes for the benefit of all students;

Viewing the differences between students as resources to support learing, rather than as problems to

be overcome;

Acknowledging the right of students to an education in their locality;

Improving schools for staff as well as for students;

Emphasizing the role of schools in building community and developing values, as well as in increase

achievement;

Fostering mutually sustaining relationships between schools and communities;

Recognizing that inclusion in education is one aspect of inclusion in society.

(Booth, 2011)

While it is vitally important that all schools are inclusive, and that pupils with SEND and disabilities

should be able to access mainstream education through appropriate training, strategies and support, we all

need to be realistic and realize that this is not always an option.

Special needs provision is often the most viable option for some pupils, but inclusion must not be taken

for granted in these settings, as it can be as difficult to achieve as it is in the mainstream school.

Inclusion can be hard work. Consider a class of eight pupils in a special school. The school caters for all

aspects of SEND and there is full inclusion in the sense that all classes have a wide range of abilities and

needs. But what about the planning? What about the environment? What about the resources? What about

the delivery? Children with different needs may require different provision. All of these aspects must be

inclusive, and this must be inclusive, and this may be one of your greatest challenges, but having first-hand

experience of inclusive practice is the best way to learn.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 13 of 27

PUPILS ON THE ASD SPECTRUM

Most pupils who have autism as an identified need will be able to fully or partly included within the usual

classroom routine. However, some specific provisions may have to be considered for these pupils, including

the use of quiet areas, individual workstations, clear routines, visual time-tables picture exchange

communication and social stories.

MAKATON

This method of signing support communication and is now used widely in both special and mainstream

settings. It is used by many pupils to communicate and is accepted as the norm in some classes or settings.

Makaton gives you the ideal opportunity to learn alongside your pupils, many of whom will be more than

eager to point out your mistakes. The speech and language therapist will be able to offer you training

manuals to support Makaton, and by learning this technique you are addressing inclusive practice.

BEHAVIOR MANAGEMENT

Just as the behavior in a special school can seem extreme, so can the strategies to control it. If a pupil is

deemed as being a danger to themselves or others, and all other strategies have failed, the pupil may have

to be handled using trained technique. Under no circumstances should you be involved in this, as only staff

members fully trained in the techniques of handling are allowed to use these. Most school use the Team

Teach method, which ensures that all handling is carried out safely and for the shortest time possible. Staff

undergo training in order to obtain a Team Teach qualification, and this must be updated and renewed every

year.

SUGGESTED TASK TO BE UNDERTAKEN

Teaching activities need to enable trainees to observe, assist and then teach small groups, and if

possible to gain whole-class/group teaching experiences, including the management of support staff. This

can be undertaken through the following phases.

1. Introductory Phase- shadowing both the teacher and teaching assistant, assisting with lessons and

participating in discussions about pupil’s needs or the SEND provision.

2. Development Phase- increased involvement with teaching and learning by taking increased

responsibility for planning, assessing, recording and the teaching of individuals or small groups of

pupils. During this phase you might also wish to team teach with the teacher.

3. Consolidation Phase- improving the quality of your teaching through feedback and self-reflection.

Suggested activities include planning and leading a whole morning or afternoon session including

breaks; managing teaching assistants, and reflection and analysis by planning for a second lesson

following feedback from an initial session.

It is envisaged that trainees working with pupils with severe and/or complex needs and/or disabilities will

require extra support and supervision. This does not detract from your abilities, but is to ensure the well-

being and safety of both you and the pupils.

POSSIBLE DIRECTED TASKS

The following tasks will help to develop your knowledge and understanding of SEND provision:

1. Acoustic experience of classrooms- explore how easy/difficulty it is for pupils to hear the teacher in

different environments. Consider the physical environment, the teacher’s delivery and the pupil’s

ability to hear. Concentrate on aspect that can be governed by the teacher.

2. Physical accessibility and circulation of pupils in the school- how easy and difficult is it for pupils

to move around the school? Observe pupil movements in differing situations How has the physical

environment been adapted to facilitate movement around the school?

3. Organization of classroom for learning- make observations of how teachers adapt classrooms

according to pupil needs. How does classroom organization relate to the learning objectives of the

lesson, the individual learning goals of pupils, and fostering independence in learning?

4. Production of learning materials and resources- consider the resources produced by the teacher

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 14 of 27

and teaching assistants. Discuss with them the roles in this process. Establish with class staff how

the materials and resources are designed to foster learning, how the materials enable a diversity of

learning needs to be met, and how staff decide on the content and form of the materials and

resources.

5. Planning of lessons and learning objectives- interview teachers and teaching assistants both

collectively and individually to understand the process of lesson planning and the setting of

objectives.

6. Learning and development in informal situations- observe pupils in informal settings such as the

playground or dining hall, focusing on pupils’ speaking and listening skills.

7. Storytelling and retelling- the aim of this task is to find effective ways of storytelling using sensory

stories. Observe a sensory story session first and then plan and deliver one. This will give opportunity

to create a wide range of resources, props and materials, and will help you to understand the wide

range of communication methods that can be deployed.

(Tasks taken from TDA, 2OO8)

ASSESSMENT

Assessment is a vital tool in the special needs setting, especially with pupils who do not ‘fit’ the normal

assessment criteria. Pupils with SEND tend to learn in a very ‘fragmented’ way, often achieving a desired

target one day, while being unable to do so the next day. They may often complete only a small part of a

learning target, but then show skills and abilities that match a lower or even higher target.

It is very important, therefore, that the assessment ‘fits’ the pupil rather than the pupil ‘fitting’ the

assessments. Many schools devise their own methods of assessment, while some buy in commercially

produced materials.

ACTIVITY 14-15

Discussion Points and Exercise Questions

Direction: Read and understand this module. Provide what is being asked. Submit your output as a file.

TASKS:

Make a course resource handbook along these lines:

1. Your Philosophy of Special Education. What is special education? How do special education and

regular education relate to one another? Put some quotations or inspirational messages here about

your own reflections on special education.

2. Specific Disabilities. Determine your tutee’s learning disabilities and complete what is asked.

a. Definition of the exceptionality

b. Implications of teaching in each area of disability and modifications of teaching

approaches. What channels can be used to work with? Explain general approaches that work

with specific disabling condition. Provide activities and materials (commercial or teacher-made)

most suited to the particular disability (e.g., how the blind can use tape recorders to both record

the lesson and write a paper; how a teacher might assign a talking book to a student with learning

disabilities. (5points each- total of 35 points)

c. Specific technology used frequently by people with certain disabilities. For example, the TTY can

be used by individuals with hearing impairment o enable them to use the telephone system. (5

points each, total of 35 points)

3. Service Learning Experience (50 points)

Students may choose one of the following two activities for this component of the handbook.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 15 of 27

OBSERVATIONS: Complete four (4) observations of children with exceptionalities throughout

the course of the semester. You may select each observation population. Use a non-

discriminatory method of data collection during the observation to organize your notes, and

then provide a reflection on what you learned about the student and about his or her

educational (or social, family) experience. Relate your own reflections to the information

presented in class (module, textbook or other sources). For this observational task, you are to

observe children (ages 0-18) in educational, social and/or family environments.

ONLINE TUTORING: Complete four session of tutoring with a student with an exceptionality.

Create a tutoring portfolio that indicates the goal of the tutoring relationship, the objectives of

each tutoring session, activities conducted during each session, assessment of session of how

the theoretical principles of educational psychology apply to this practical experience. Your

tutoring portfolio must contain references to the textbook and other reading for each session.

Your portfolio may include photographs, illustrations and sample student work in addition to

you written reflections on each session.

* The student is responsible for selecting the tutee and prior approval to from the instructor

with regard to the tutoring situation is mandatory. Students are allowed to conduct their

activity within their specified area only (1vs1 online tutorial via zoom or messenger).

Attached to the next page is the parent’s consent.

PARENT’S CONSENT

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

One of the requirements of third year students of College of Teacher Education with the subject EDUC

311: Foundations of Special and Inclusive Education, is to conduct a tutorial session to create a tutoring

portfolio that indicates the goal of the student-teacher tutoring relationship, the objectives of each tutoring

session, activities conducted during each session and assessment of session to this practical experience.

Due to this COVID-19 pandemic, the student is allowed to conduct his/her activity only at his/her home (1vs1

online tutorial via zoom, skype, messenger, et cetera).

In connection with this, I allow ______________________________ to undergo a 30-minute tutorial

session (8 sessions) within 2 weeks and must be completed within this given time frame which will be

conducted by ___________________________, an education student of South East Asian Institute of

Technology as a requirement for the fulfillment of his/her said subject.

_________________________________

Guardian’s Signature over Printed Name

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 16 of 27

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 17 of 27

National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South Cotabato

COLLEGE OF TEACHER EDUCATION

___________________________________________________

LEARNING MODULE

FOR

EDUC 311: FOUNDATION OF SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

_____________________________________________________

WEEK 16

__________________

WEEK 16

THE ROLE OF THE SENDCO

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE SENDCo ROLE

The Code of Practice (DfE,1994) placed as statutory obligation on all schools to appoint a teacher with

responsibility for the coordination of educational provision for pupils with SEND. The Teacher Training

Agency (TTA) produced a set of nation standards for SENDCos in 1998, enabling them to audit their

knowledge and skills, and identify their professional development needs. These were offered as guidance. At

this time, professional development courses for SEND coordination were introduced by local authorities and

higher education institutions to provide SENDCos with professional training and accreditation, although

there was no mandatory requirement for SENDCos to participate in the training (Layton, 2005).

The TTA stated that:

The SENDCO, with the support of the head teacher and governing body, takes responsibility for the

day-to-day operation provision made by the school for pupils with SEN and provides professional

guidance… in order to secure high quality teaching and the effective use of resources to bring about

improved standards of achievement for all pupils.

(TTA, 1998: 5)

The focus for SENDCos was to coordinate four man areas of SEN provision:

Strategic direction and development of SEND provision;

Teaching and learning;

Leading and managing staff;

Efficient and effective deployment of staff and resources.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 18 of 27

The SENDCo was responsible for developing a whole-school approach to the coordination of SEN, but

there was never an expectation that the SENDCo would have exclusive responsibility for pupils whose

learning needs threatened to challenge the teaching approaches or classroom organizations with which

teaching colleagues were more familiar (Layton, 2005: 54)

When the 1994 Code of practice was revised in 2001 (Dfes, 2001) the new code explicitly made

reference to the fact that many mainstreams primary and secondary schools find it effective for the SENDCo

to be a member of the senior leadership team (DFES, 2001:51, 66). This was later reinforced in the Labor

government’s SEND strategy Removing Barriers to Achievement, which stated that:

We want schools to see the SENDCO as a key member of the senior leadership team, able to

influence the development of policies for whole school improvement.

(Dfes,2004:58 para 3.14)

The House of Common’s Education and Skills Select Committee (2006) recommended that the

SENDCo should be a member of the school leadership team, but this was not made a statutory requirement

(Pearson, et. al, 2014). However, subsequent legislation (DCSF, 2008) stated that all newly appointed

SENDCos would be required to undertake that National Award for SEND Coordination in which they would

be required to demonstrate their ability to influence strategically the development of an inclusive culture,

policies and practices across the whole school.

The role of SENDCO in promoting whole-school inclusion over their specialist knowledge of SEND-

related issues has to some extent led to ambiguity in relation to the requirements of the role (Rosen-Webb,

2011). The debate focuses on whether the SENDCo is a ‘change agent’ for whole school inclusion (Hallet

and Hallet, 2010) or whether the role should be more focused on the strategies to support individual

students with highly specific needs. Additionally, the notion of the SEND ‘expert’ has been subjected to

critical debate. It has been emphasized that all teachers and teachers of pupils with SEND (Norwich, 1990)

and that the introduction of a specialist role may make it easier for teachers to effectively abdicate their

responsibilities for education of pupils with SEND to those with more experience, knowledge and higher

quaalifications.

THE ROLE OF THE SENCO

The SENCO has a critical role to play in ensuring that children with special educational needs and

disabilities within a school receive the support they need.

Gradually over the years the status and import of the role has developed with successive guidance

validating and substantiating the role.

In the most recent Code of Practice, the SENCO must be a qualified teacher (why ever were they not!)

and a newly appointed SENCO must achieve a National award in Special Educational Needs Coordination

within three years of appointment.

The SENCO has ‘an important role to play with the head teacher and governing body in determining the

strategic development of SEN policy and provision and will be most effective if they are part of the school

leadership team’.

The type of responsibilities a SENCO has are:

Overseeing the day-to-day operation of the school’s SEN policy.

Supporting the identification of children with special educational needs.

Coordinating provision for children with SEN.

Liaising with parents of children with SEN.

Liaising with other providers, outside agencies, educational psychologists and external agencies.

Ensuring that the school keeps the records of all pupils with SEN up to date.

Clearly the role of the SENCO as a leader in a school has never been more important.

CHALLENGES OF THE SENDCO ROLE

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 19 of 27

Research (Cole and Johnson, 2004) has indicated that the role of the SENDCO is challenging, stressful

and demanding on many levels due to limited time, resources, funding and fear of parental litigation. Very

often SENDCos appear to be overworked but remain completely committed to their struggle on behalf of

children with special education needs (Cole, 2005b: 298).

Education operates within a quasi-market that privileges school performance, parental choice and

engenders a culture of competition. According to Cole, within this contentious context, the role of the

SENCO was never going to be an easy one (2005b: 296). While SENDCos tend to be advocates of

inclusion and agents of change, they are also accountable for the achievement of pupils with SEN and/or

disabilities. Their practice is often underpinned by the principles of equity and social justice, and an

unquestionable commitment to care (Cole, 2005b). However, these values need to be balanced against

market principles, and it is possible that SENDCos might increasingly have to sacrifice their deep-rooted

professional values in order to focus on maximizing the performances of pupils with SEND with respect to

school performance indicator.

THE ROLE OF THE SENDCo IN THE NEW CODE OF PRACTICE

The Code of Practice (Dfe, 2015) includes several statements about the roles and responsibilities of the

the SENDCo. These include:

Overseeing the day-to-day operation of the school’s SEND policy;

Coordinating provisions for pupils with SEND;

Liaising with the designated safeguarding teacher where a looked-after child has SEND;

Advising colleagues on a graduated approach to send support;

Advising on the use of the delegated budget or other resources that have been allocated;

Liaising with parents of pupils with SEND;

Establishing links with other education settings and outside agencies liaising with potential future

providers of education;

Ensuring that the school is fully compliant with the statutory obligations of the Equality Act 2010;

Ensuring that SEND records are kept up to date;

Specific statements relating to the roles and responsibilities of SENDCos taken directly from the Code of

Practice are listed below:

6.84 Governing bodies maintained mainstreams schools and the proprietors of mainstream academy

schools (including free schools) must ensure that there is a qualified teacher designated as SENCO for the

school.

6.85 The SENCO must be a qualified teacher working at school. A newly appointed SENCO must be a

qualified teacher and, where they have not previously been the SENCO at that or any other relevant school

for a total period of more than twelve months, they must achieve a National Award in Special Educational

Needs Co-ordination within three years of appointment.

6.86 A National Award must be a postgraduate course accredited by a recognized higher education

provider. The National College for teaching and Leadership has worked with providers to develop a set of

learning outcomes. When appointing staff or arranging for them to study for a National Award schools

should satisfy themselves that the chosen course will meet these outcomes and equip the SENCO to fulfill

the duties outlined in this Code. Any selected course should be at least equivalent to 60 credits at

postgraduate study.

6.87 The SENCO has an important role to play with the head teacher and governing body, in determining

the strategic development of SEN policy and provision in the school. They will be most effective in that role if

they are part of the school leadership team.

6.88 The SENCO has day-to-day responsibility for the operation of SEN policy and coordination of specific

provision made to support individual pupils with SEN, including those who have EHC plans.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 20 of 27

6.89 The SENCO provides professional guidance to colleagues and work closely with staff, parents and

other agencies. The SENCO should be aware of the provision in the Local Offer and be able to work with

professionals providing a support role to families to ensure that pupils with SEN receive appropriate support

and high-quality teaching.

6.90 The key responsibilities of SENCO may include:

Overseeing the day-to-day operation of the school’s SEN policy

Coordinating provisions for pupils with SEN

Liaising with the relevant designated Teacher where a looked-after pupil has SEN

Advising on the graduated approach to SEN support

Advising on the development of the school’s delegated budget and other resources to meet pupil’s

need effectively

Liaising with parents of pupils with SEN

Liaising with early years’ providers, other schools, educational psychologists, health and social care

professionals, and independent or voluntary bodies

Being a key point of contact with external agencies, especially the local authority and its support

services

Liaising with potential next providers of education to ensure a pupil and their parents are informed

about options and a smooth transition is planned

Working with the head teacher and school governors to ensure that the school meets its

responsibilities under the Equality Act 2010 with regard to reasonable adjustment and access

arrangements

Ensuring that the school keeps the records of all pupils with SEN up to date

6.91 The school should ensure that the SENCO has sufficient time and resources to carry out these

functions. This should include providing the SENCO with sufficient administrative support and time away

from teaching to enable them to fulfill their responsibilities in a similar way in other important strategic roles

within school.

6.92 It may be appropriate for a number of smaller primary schools to share a SENCO employed to work

across the individual schools, where they meet the other requirements set out in this chapter of the Code.

Schools can consider this arrangement where it secures sufficient time away from teaching and sufficient

administrative support to enable the SENCO to fulfill the role effectively for the total registered pupil

population across all of the schools involved.

6.93 Where such a shared approach is taken the SENCO should not normally have a significant class

teaching commitment. Such a shared SENCO role should not be carried out by the teacher by head teacher

at one of the schools.

6.94 Schools should review the effectiveness of such a share SENCO role regularly and should not persist

with it where there is evidence of a negative impact on the quality of SEN provision, or the progress of the

pupils with SEN.

(DFE, 2015: 108-9)

End of 16th Week

---------------------------------------------Nothing Follows--------------------------------------

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 21 of 27

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 22 of 27

National Highway, Crossing Rubber, Tupi, South Cotabato

COLLEGE OF TEACHER EDUCATION

___________________________________________________

LEARNING MODULE

FOR

EDUC 311: FOUNDATION OF SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

_____________________________________________________

WEEK 17

________________________

WEEK 17

SKILLS FOR COLLABORATING WITH PROFESSIONALS AND PARENTS

1. Listening Skills

The skills required for effective listening are outlined below and discussed in more detail elsewhere

(see Hornby et al. 2003). These skills are underpinned by the work of Carl Rogers who emphasized the

importance of empathic understanding, genuineness, and respect in developing facilitative relationships

with others (Rogers 1980).

a. Attentiveness. Effective listening requires a high level of attentiveness. This involves focusing one’s

physical attention on the person being listened to and includes several components, which are

outlined below.

b. Eye Contact. The importance for the listener of maintaining good eye contact throughout the

interview cannot be overemphasized. For situations in which listeners feel uncomfortable with direct

eye contact, it is usually satisfactory for them to look at the speakers’ mouth or the tip of their nose

instead.

c. Facing Squarely. To communicate attentiveness, it is important for the listener to face the other

person squarely or at a slight angle. Turning one’s body away from another person suggests that you

are not fully paying attention to them.

d. Leaning Forward. Leaning slightly forward, toward the person being listened to, communicates

attentiveness. Alternatively, leaning backward gives the impression that you are not listening, so

should be avoided.

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 23 of 27

e. Open Posture. Having one’s legs crossed, or even worse one’s arms crossed, when listening gives

the impression of a lack of openness, as if a barrier is being placed between the listener and the

person talking. Attentiveness is therefore best communicated by the adoption of an open posture with

both arms and legs uncrossed.

Non-distracting Environment

The room used should be as quiet as possible with the door kept closed to avoid distractions. Telephone

calls can be put on hold and a “meeting in progress” sign hung on the door. Within the room, the chairs used

should be comfortable with no physical barriers, such as desks or tables, between the speaker and the

professional who is listening.

Passive Listening

Passive listening involves using a high level of attentiveness combined with other skills. These are

invitations to talk, nonverbal clues, open questions, attentive silence, avoiding communication blocks, and

minimizing self-listening.

Nonverbal Clues

There are various sounds or short words that are often known as “nonverbal clues,” because they let the

speaker know that you are paying attention to them without interrupting the flow. For example, “Go on,”

“right,” “Huh Huh,” “Mm Mm.” It is particularly important to use these while listening to someone on the

telephone because the speaker cannot gauge the listener’s attentiveness through the usual visual clues.

Avoiding Communication Blocks

Certain types of comment tend to act as blocks to the communication process and therefore should be

avoided (Gordon 1970). When used they stop people from exploring their concerns and ideas. A common

example is reassurance, such as saying “Don’t worry, it will work out all right.” Other types of blocks that are

particularly annoying to parents are denial or false acknowledgment of feelings, such as suggesting that

parents should “Look on the bright side” or telling them “I know exactly how you feel.” More blatant blocks to

communication are criticism, sarcasm, and advice giving. Other common blocks involve diverting people

from the topic, either directly or by the use of excessive questioning or by excessive self-disclosure when

people go on about themselves or others they have known who have had similar problems. Further blocks

involve moralizing, ordering, or threatening, that is, telling people what they ought or must do. Finally, there

are blocks in which diagnosis or labeling is used, for example, telling someone that they are “a worrier.” All

these blocks tend to stifle the exploration of concerns or ideas and are therefore best avoided

Active Listening

Active listening involves trying to understand what the person is feeling and what the key message is in

what they are saying, then putting this understanding into your own words, and feeding it back to the person

(Gordon 1970). Thus, active listening involves the listener being actively engaged in clarifying the thoughts

and feelings of the person they are listening to. It builds on attentiveness, passive listening, and also

paraphrasing, in that the main aspects of what is being communicated are reflected back to the person. This

is done to develop empathy and provide a kind of “sounding board” to facilitate exploration and clarification

of the person’s concerns, ideas, and feelings.

Gordon (1970) suggested that certain attitudes are essential prerequisites to active listening. These are:

The listener must really want to hear what the other person has to say.

The listener must sincerely want to help the other person with his or her concern.

The listener must be able to respect the other person’s feelings, opinions, attitudes, or values even

though they may conflict with his or her own.

The listener must have faith in the other person’s ability to work through and solve his or her own

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 24 of 27

problems.

The listener must realize that feelings are transitory and not be afraid when people express strong

feelings such as anger or sadness.

The process of active listening involves reflecting both thoughts and feelings back to the speaker. The

speaker’s key feeling is fed back along with the apparent reason for the feeling. When learning how to use

active listening it is useful to have a set of formula to follow. The formula “You feel.... because......” is typically

used

. For example: You feel frustrated because you haven’t finished the job.

You feel delighted because she has done so well.

When people gain confidence in their use of active listening, the formula is no longer needed and

thoughts and feelings can be reflected back in a more natural way. For example, “You are angry about the

way you were treated,” “You’re sad that it has come to an end,” You were pleased with the result, and “You

were annoyed by her manner.”

However, active listening involves much more than simply using this formula. It requires listeners to set

aside their own views in order to understand what the other person is experiencing. It therefore involves

being aware of how things are said, the expressions and gestures used, and, most importantly, hearing what

is not said but which lies behind what is said. The real art in active listening is in feeding this awareness

back to the person accurately and sensitively. This, of course, is very difficult, but the beauty of active

listening is that you don’t have to be completely right to be helpful. An active listening response which is a

little off the mark typically gets speakers to clarify their thoughts and feelings further. However, active

listening responses that are way off the mark suggest to the speaker that the other person isn’t listening and

therefore can act as blocks to communication.

2. ASSERTION SKILLS

Assertiveness involves being able to stand up for one’s own rights while respecting the rights of others

and being able to communicate one’s ideas, concerns, and needs directly, persistently, and diplomatically. It

also involves being able to express both positive and negative feelings with openness and honesty, as well

as being able to choose how to react to situations from a range of options. Teachers and other

professionals, such as psychologists and counselors, need to use assertion skills in working with parents

and for collaborating with their practitioner colleagues. Professionals will have to deal with criticism or

aggression from time to time and will need to make and refuse requests as well as be able to give

constructive feedback. Finally, they will be called on to help solve problems. The skills involved in these

situations are outlined below.

Basic Elements of Assertiveness

There are three aspects of assertiveness that apply in any situation. These are:

1. Physical Assertiveness

2. Vocal Assertiveness

3. Assertion Muscle Levels

DEALING WITH AGGRESSION

Kroth (1985) has provided some guidelines for dealing with aggressive behavior from parents or

colleagues. Professionals decrease their effectiveness when they:

Argue with a person who is behaving aggressively

Raise their voices or begin to shout

Become defensive and feel they have to defend their position

Attempt to minimize the concern which the other person is expressing

Take responsibility for problems which are not of their making

Make promises which they won’t be able to fulfill All of these responses are the ones that are

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 25 of 27

commonly used by people confronted with aggression, but they are likely to inflame the situation

and make the other person more aggressive.

The following responses are far more likely to lead to a constructive resolution of the situation. Professionals

increase their effectiveness when they:

Actively listen to the other person

Speak softly, slowly, and calmly

Ask for clarification of any complaints which are vague

Ask what else is bothering them in order to exhaust their list of complaints

Make a list of their concerns, go through the list, and ask if it’s correct and complete

Use the techniques of problem solving, discussed below, to work through the list of concerns in

order to resolve problems or conflicts, starting with the one of highest priority to the other person

3. COUNSELING SKILLS

The counseling model that is proposed for use with practitioners and parents of children with SEND is

based on a general approach to the use of counseling skills that can be used with children and adults in a

wide variety of situations. It is grounded in the belief that individuals have the ability to solve their own

problems given appropriate support (Rogers 1980). The model involves a three phase approach to

counseling with phases of listening, understanding, and action planning. It is a problem-solving approach to

counseling which was developed from previous models by Egan (1982) and Allan and Nairne (1984) and

that I have used for many years. The majority of parents will not ask for counseling directly, but will typically

go to teachers with concerns about their children. If professionals use listening skills in order to help parents

explore their concerns, then the parents’ need for help will emerge. This is when it is useful for professionals

to be able to help parents by using basic counseling skills. Parents are much more likely to be willing to talk

about their concerns with someone who is working directly with their child, such as a teacher, than with a

professional counselor who they do not know. What teachers and other professionals need therefore is a

counseling model which is practical, simple to learn, and easy to use. They also need to have contact with

other professionals, such as psychologists or counselors, who can support them in its use and be someone

to refer on to when situations start to go beyond their level of competence.

The rationale for using such a model is based on the idea that any problem or concern which parents

raise with professionals can be dealt with by taking them through the three phases of the model in order to

help them find the solution that best suits their needs. First of all, the professional uses the skills of the

listening phase to establish a working relationship with parents, to help them open up, and to explore any

concerns they have. Then, the professional moves on to the second phase, using the skills of the

understanding phase in order to help parents get a clearer picture of their concerns, develop new

perspectives on their situation, and suggest possible goals for change. Finally, the professional moves on to

the third phase, of action planning, in which possible options for solving parents’ problems are examined and

plans for action are developed. Thus, different skills are needed at each phase of the model: skills for

listening in the first phase, skills for understanding in the second phase, and skills for action planning in the

third phase.

ORGANIZATION OF PARENT GROUPS AND WORKSHOPS

A parent workshop format that has been found useful in a wide range of contexts is outlined below, with

more details in Hornby and Murray (1983). A summary of the main aspects of workshop organization is

presented first.

FORMAT FOR PARENT WORKSHOPS

The format for parent workshops that has been found the most effective is one that consists of four

sections: introduction, lecture presentation, small-group discussion, and summary (Hornby and Murray

1983).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 26 of 27

Professionals who work with children with SEND, such as educational psychologists, social workers,

school counselors, and teachers, need to have good interpersonal communication skills in order to work

effectively with parents and with each other. Listening, assertion, and counseling skills have therefore been

elaborated in this chapter. The skills required for effective listening that were discussed include

attentiveness, passive listening, paraphrasing, and active listening. The assertion skills that were described

include techniques for making and refusing requests, giving constructive feedback, handling criticism, and

problem solving. The basic counseling skills that were discussed were set within a three phase problem-

solving model of counseling which involves listening, understanding, and action planning skills. The

knowledge and skills required for working with groups of parents were outlined, including the benefits of

group work, leadership skills, group dynamics, and the format and organization of parent workshops. The

following chapter discusses the importance of professionals in the field of inclusive special education being

empowering individuals who facilitate the development of parents as people rather than simply helping them

to overcome their difficulties. This includes discussion of the stress management skills that professionals

need in order to work in this field and which they can also teach to parents and their colleagues.

End of 17th Week

----------------------------------------Nothing Follows--------------------------------------

EDUC 311: Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education

SOUTH EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC.

Page 27 of 27

You might also like

- Chapter 6 Learners With Additional NeedsDocument38 pagesChapter 6 Learners With Additional NeedsDIMPZ MAGBANUA100% (3)

- Final Coverage Foundations of Special and Inclusive EducationDocument28 pagesFinal Coverage Foundations of Special and Inclusive EducationSheena LiagaoNo ratings yet

- MODULE 2 LESSON 6 FOUNDATION OF SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATION Updated3Document30 pagesMODULE 2 LESSON 6 FOUNDATION OF SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATION Updated3ALLEIHSNo ratings yet

- Brown Modern Group Project PresentationDocument32 pagesBrown Modern Group Project PresentationHannah andrea HerbillaNo ratings yet

- Educ 1. Learners With Additional Needs, Chapter Vi.Document29 pagesEduc 1. Learners With Additional Needs, Chapter Vi.Mariane Joy TecsonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 CompilationDocument36 pagesChapter 6 CompilationJunrel J Lasib DabiNo ratings yet

- Group 7 Report Profed 105Document18 pagesGroup 7 Report Profed 105steffiii dawnNo ratings yet

- Educ 211Document29 pagesEduc 211ismael celociaNo ratings yet

- Sped Gifted ReportDocument25 pagesSped Gifted Reportrowena OpocNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument4 pagesChapter IjhonaNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 How To Support SEN Children in The ClassroomDocument10 pagesUnit 3 How To Support SEN Children in The ClassroomВиктория ЕрофееваNo ratings yet

- CSTC College module explores learners with additional needsDocument17 pagesCSTC College module explores learners with additional needsCharles Data100% (1)

- Inclusive Educ PDFDocument12 pagesInclusive Educ PDFHannahNo ratings yet

- I-Fla 1Document5 pagesI-Fla 1nekirynNo ratings yet

- Ed 509Document5 pagesEd 509bobbyalabanNo ratings yet

- Tayabas Western Academy: Date SubmittedDocument5 pagesTayabas Western Academy: Date SubmittedPaul Arvin DeChavez Limbo100% (1)

- Characteristics of Gifted and TalentedDocument10 pagesCharacteristics of Gifted and TalentedArlea TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Graduate School Master of Arts in Special Education (MAS) Special Education Journal ReviewDocument5 pagesGraduate School Master of Arts in Special Education (MAS) Special Education Journal ReviewVince IrvineNo ratings yet

- Module 3-Special and Inclusive EducationDocument7 pagesModule 3-Special and Inclusive EducationLyn PalmianoNo ratings yet

- R2 Intro To SPEDDocument29 pagesR2 Intro To SPEDTobyprism TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Teaching Tools:: Diverse Populations & Learning StylesDocument30 pagesTeaching Tools:: Diverse Populations & Learning StylesPaula BleiraNo ratings yet

- Finals Module4, Educ104Document16 pagesFinals Module4, Educ104mariejanine navarezNo ratings yet

- Assignment ON Paper: 203: Inclusive Education Topic: Educational Programmes FOR Learning Disabled and Slow LearnerDocument11 pagesAssignment ON Paper: 203: Inclusive Education Topic: Educational Programmes FOR Learning Disabled and Slow LearnerMathew MarakNo ratings yet

- Raising Bright Sparks: Book 2 -Teaching Gifted StudentsFrom EverandRaising Bright Sparks: Book 2 -Teaching Gifted StudentsNo ratings yet

- Gifted Education and Gifted Students: A Guide for Inservice and Preservice TeachersFrom EverandGifted Education and Gifted Students: A Guide for Inservice and Preservice TeachersNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: What Does It Mean?: Group 7Document6 pagesIntelligence: What Does It Mean?: Group 7Rias Wita SuryaniNo ratings yet

- Online AssignmentDocument10 pagesOnline AssignmentceebjaerNo ratings yet

- Students Who Are GiftedDocument24 pagesStudents Who Are Giftedapi-248879423No ratings yet

- Title: Advanced Educational Technologies in The 21 Century Era Name: Jacklyn M. Tuquero Section: GED 108-C10Document6 pagesTitle: Advanced Educational Technologies in The 21 Century Era Name: Jacklyn M. Tuquero Section: GED 108-C10Kindred BinondoNo ratings yet

- 30 Methods To Improve Learning Capability in Slow LearnersDocument15 pages30 Methods To Improve Learning Capability in Slow Learnersparulian silalahiNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 Nature of A Science LearnersDocument11 pagesLesson 3 Nature of A Science LearnersJoann BalmedinaNo ratings yet

- SpEd 01 Guiding PrinciplesDocument3 pagesSpEd 01 Guiding PrinciplesVillaren VibasNo ratings yet

- Gifted and Talented LearnersDocument2 pagesGifted and Talented LearnersfaithpanginacoNo ratings yet

- Teaching Strategies for Diverse LearnersDocument8 pagesTeaching Strategies for Diverse LearnersJames ArellanoNo ratings yet

- 2p-Eced06 (Task 2)Document8 pages2p-Eced06 (Task 2)Mariefe DelosoNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 ThesisDocument11 pagesGrade 11 ThesisJoshy SamsonNo ratings yet

- Educ104 4-5 Week UlobDocument6 pagesEduc104 4-5 Week UlobNorienne TeodoroNo ratings yet

- Learning Task 2 CamilleDocument2 pagesLearning Task 2 CamilleCamilleNo ratings yet

- Blog PDFDocument5 pagesBlog PDFjiztjourn jiztNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 TALENTED CHILDREN WITHIN THE REGULAR CLASSROOMDocument3 pagesUnit 5 TALENTED CHILDREN WITHIN THE REGULAR CLASSROOMstacietaduran384No ratings yet

- HPGD1103 Curriculum DevelopmentDocument12 pagesHPGD1103 Curriculum DevelopmentUina JoNo ratings yet

- Ed 106 - BSED ScienceDocument9 pagesEd 106 - BSED ScienceMhel Rose BenitezNo ratings yet

- Effective Teaching Strategies of Bulacan State University - Sarmiento CampusDocument51 pagesEffective Teaching Strategies of Bulacan State University - Sarmiento CampusPerry Arcilla SerapioNo ratings yet

- Nardo, Marvin Jethro - Prof Ed 10 - Assignment #3Document6 pagesNardo, Marvin Jethro - Prof Ed 10 - Assignment #3Jayvee JaymeNo ratings yet

- Module1 Gregorio MariluzDocument3 pagesModule1 Gregorio MariluzMarsha MGNo ratings yet

- Good DayDocument11 pagesGood DayfaithpanginacoNo ratings yet

- Assignment Spring 2021: Name: ABCDocument16 pagesAssignment Spring 2021: Name: ABCFarhat AbbasNo ratings yet

- Definition, Goals, and Scope of Special and Inclusive EducationDocument7 pagesDefinition, Goals, and Scope of Special and Inclusive EducationMaia Gabriela100% (1)

- Addressing The Learning Gaps LectureDocument10 pagesAddressing The Learning Gaps LectureLymberth BenallaNo ratings yet

- Special & Inclusive Education Learners CharacteristicsDocument45 pagesSpecial & Inclusive Education Learners CharacteristicsAniway Rose Nicole BaelNo ratings yet

- Teaching Students With Special NeedsDocument15 pagesTeaching Students With Special NeedsSnaz NazNo ratings yet

- Research Paper (Odoy)Document22 pagesResearch Paper (Odoy)Honey Jean Puzon MabantaNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument8 pagesResearchRaya LalasNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Learning Among Pupils With Learning DifficultiesDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Learning Among Pupils With Learning DifficultiesSam SamNo ratings yet

- What Is Gifted - Final Web EditDocument7 pagesWhat Is Gifted - Final Web Editapi-253977101No ratings yet

- Observation 1-EmergenciesDocument16 pagesObservation 1-Emergenciesapi-584177179No ratings yet

- Effective Learning Style For The Student of Asian Institute of Science and TechnologyDocument7 pagesEffective Learning Style For The Student of Asian Institute of Science and Technologycarl seseNo ratings yet

- SPED607FINALEXAMDocument3 pagesSPED607FINALEXAMAcym Aej OdlisaNo ratings yet

- EDP 112 Final ModuleDocument90 pagesEDP 112 Final ModuleJoevan VillaflorNo ratings yet

- MAED Social Studies Adv. PedagogyDocument13 pagesMAED Social Studies Adv. PedagogyRochelenDeTorresNo ratings yet

- New Resume 001Document1 pageNew Resume 001Christian BañaresNo ratings yet

- SEMI DETAILED LESSON PLAN For Demo. FinalDocument4 pagesSEMI DETAILED LESSON PLAN For Demo. FinalChristian BañaresNo ratings yet

- Bañares, Christian John B. Educ 312: Facilitating Learner-Centered Teaching Activity #16 (Multimedia Presentation)Document5 pagesBañares, Christian John B. Educ 312: Facilitating Learner-Centered Teaching Activity #16 (Multimedia Presentation)Christian BañaresNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 Math 3RD QuarterDocument3 pagesGrade 5 Math 3RD QuarterChristian BañaresNo ratings yet

- My Guide For Ddemo TeachingDocument7 pagesMy Guide For Ddemo TeachingChristian BañaresNo ratings yet

- Good MorningDocument1 pageGood MorningChristian BañaresNo ratings yet

- Final Module EDUC 312Document30 pagesFinal Module EDUC 312Gian Henry Balbaguio Escarlan100% (1)

- Lit 114 Lesson Plan OngoingDocument2 pagesLit 114 Lesson Plan OngoingChristian BañaresNo ratings yet

- Lit 114 Lesson Plan OngoingDocument2 pagesLit 114 Lesson Plan OngoingChristian BañaresNo ratings yet

- AestheticDocument1 pageAestheticChristian BañaresNo ratings yet